How Does the Wine Sector Perform and Communicate Sustainability? The Italian Case

Abstract

:1. Introduction and Objectives of the Study

- How the Italian wine sector communicates what it does in terms of sustainability;

- The overall sustainability performance of the sector on the basis of the communication by wine producers;

- The most recurring sustainability themes and practices in wine producers’ external communication;

- The strengths and weaknesses of the Italian wine sector with regard to sustainability.

2. Materials and Methods

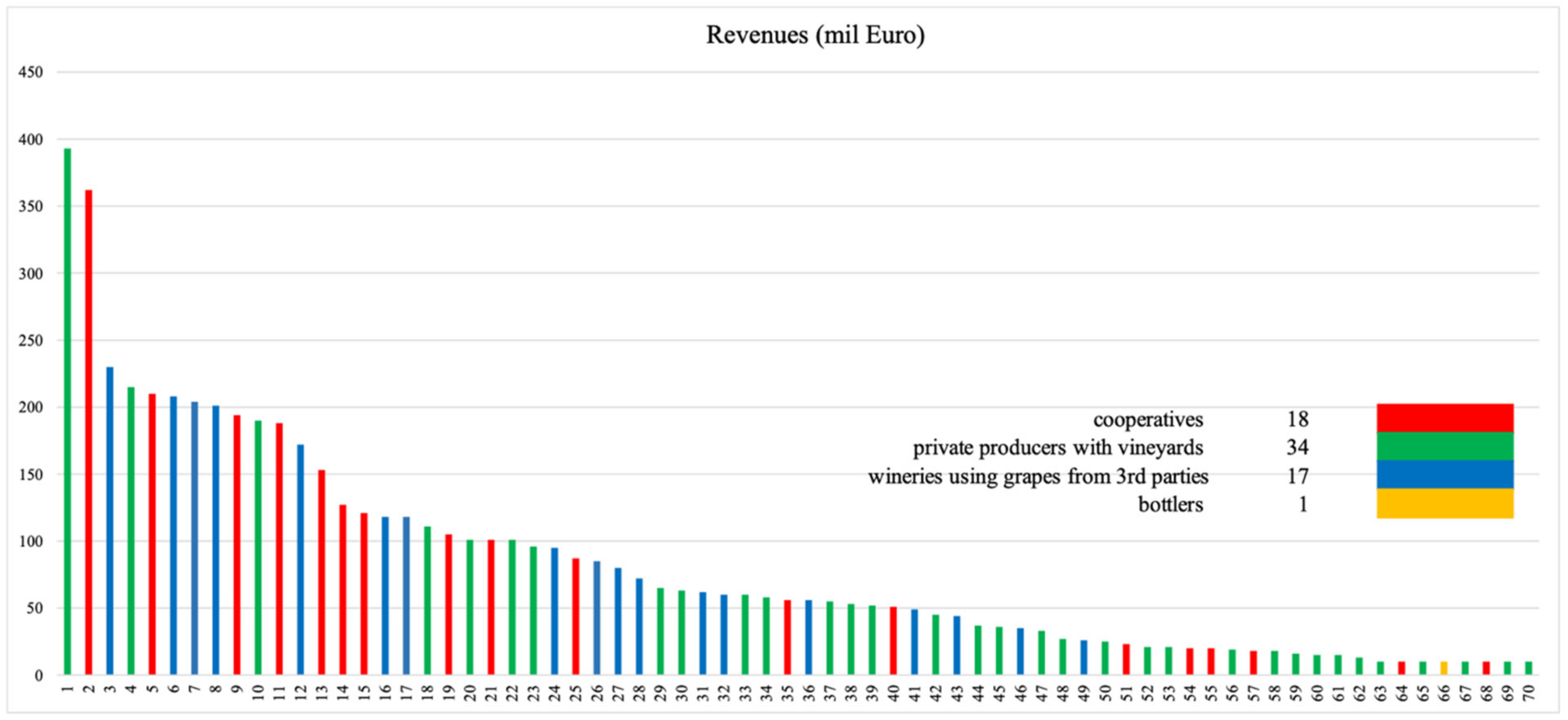

2.1. The Panel

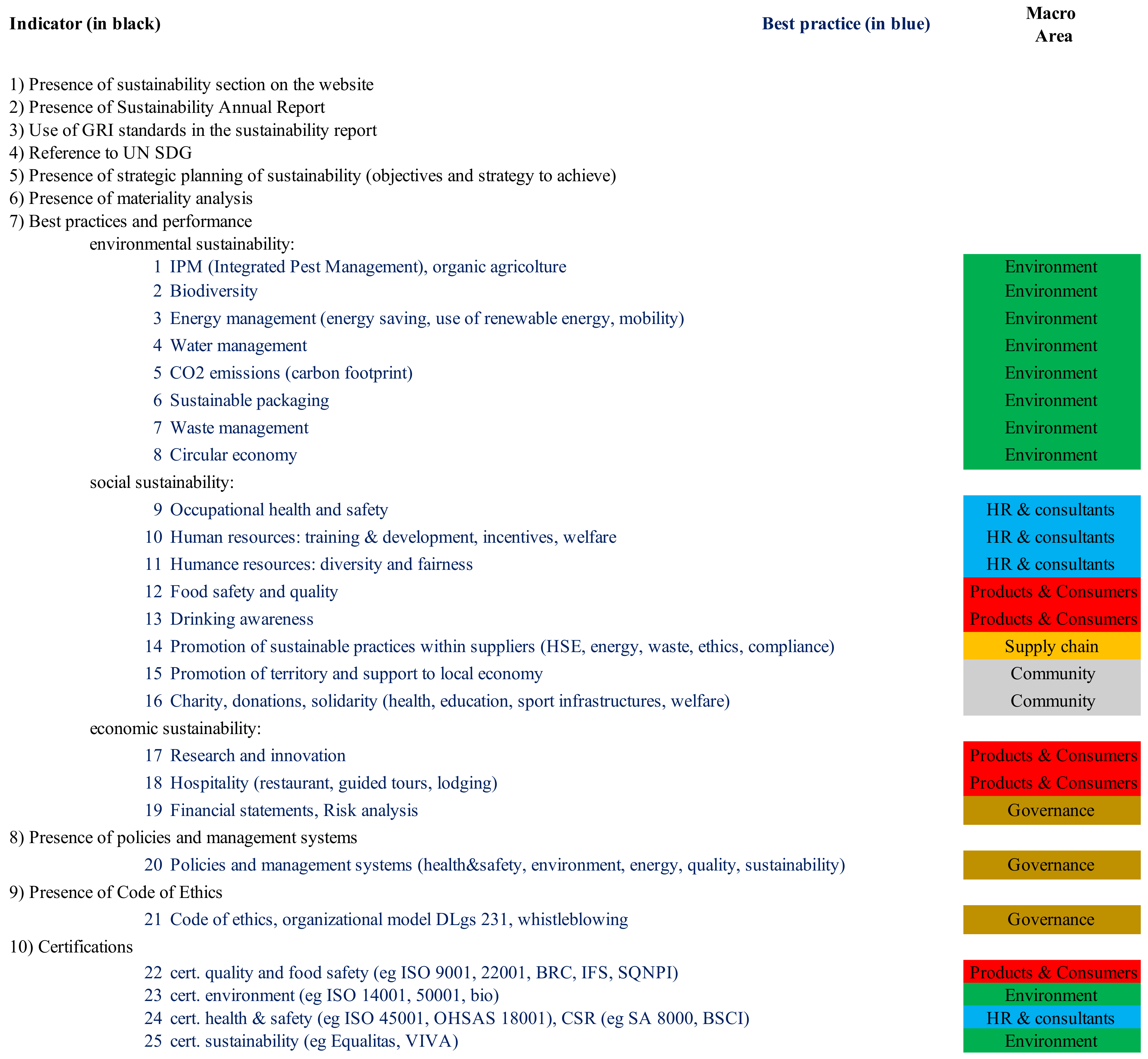

2.2. The Indicators and Sustainability Practices

- Presence of a sustainability section on the website;

- Presence of an annual sustainability report;

- Use of Global Reporting Initiative (GRI [24]) standards in the sustainability report;

- References to UN SDGs;

- Presence of strategic planning of sustainability (objectives and strategies to achieve);

- Presence of a materiality analysis;

- Best practices and performance;

- Presence of policies and management systems;

- Presence of a code of ethics;

- Certifications.

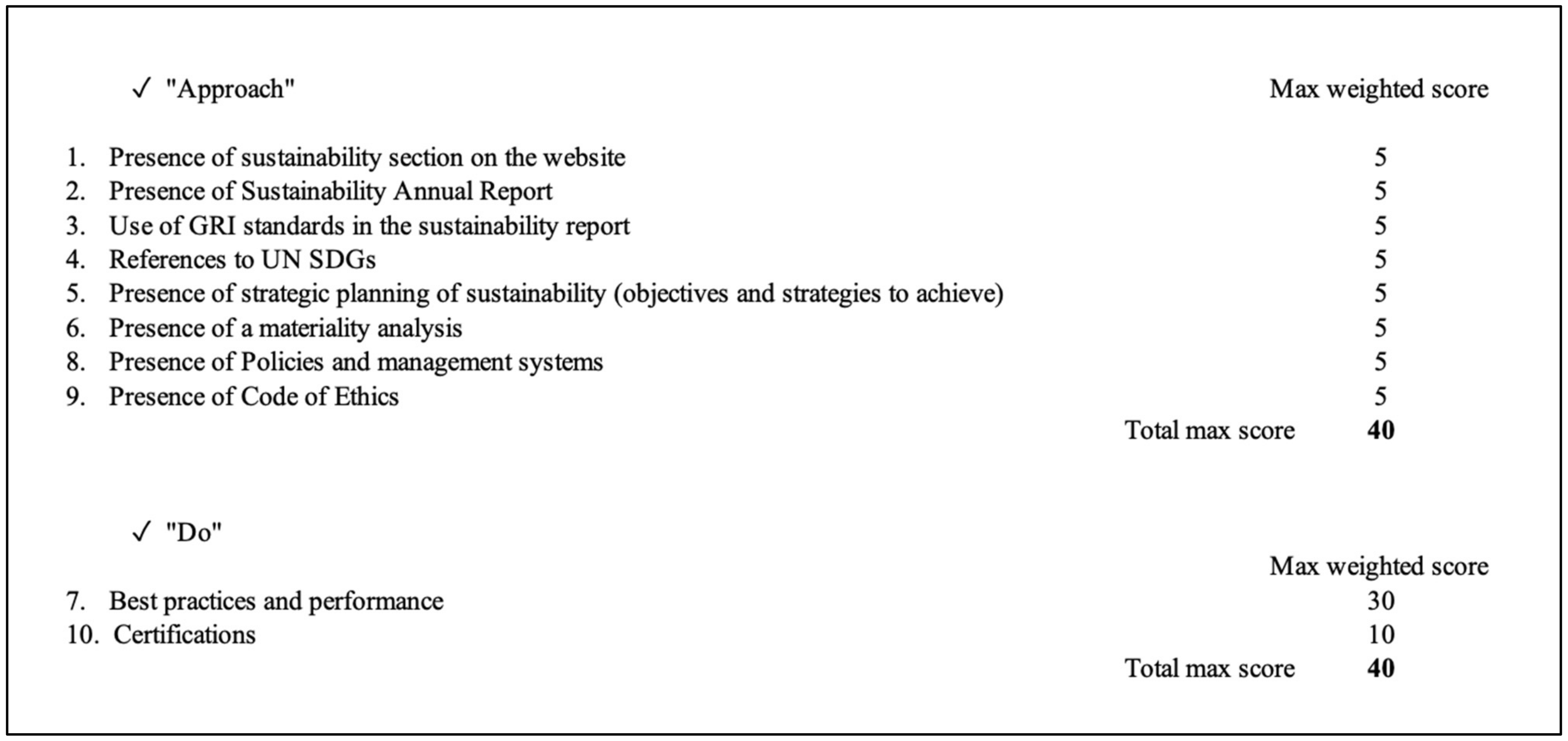

2.3. The Scoring Model

3. Results

3.1. The Overall Performance of the Panel

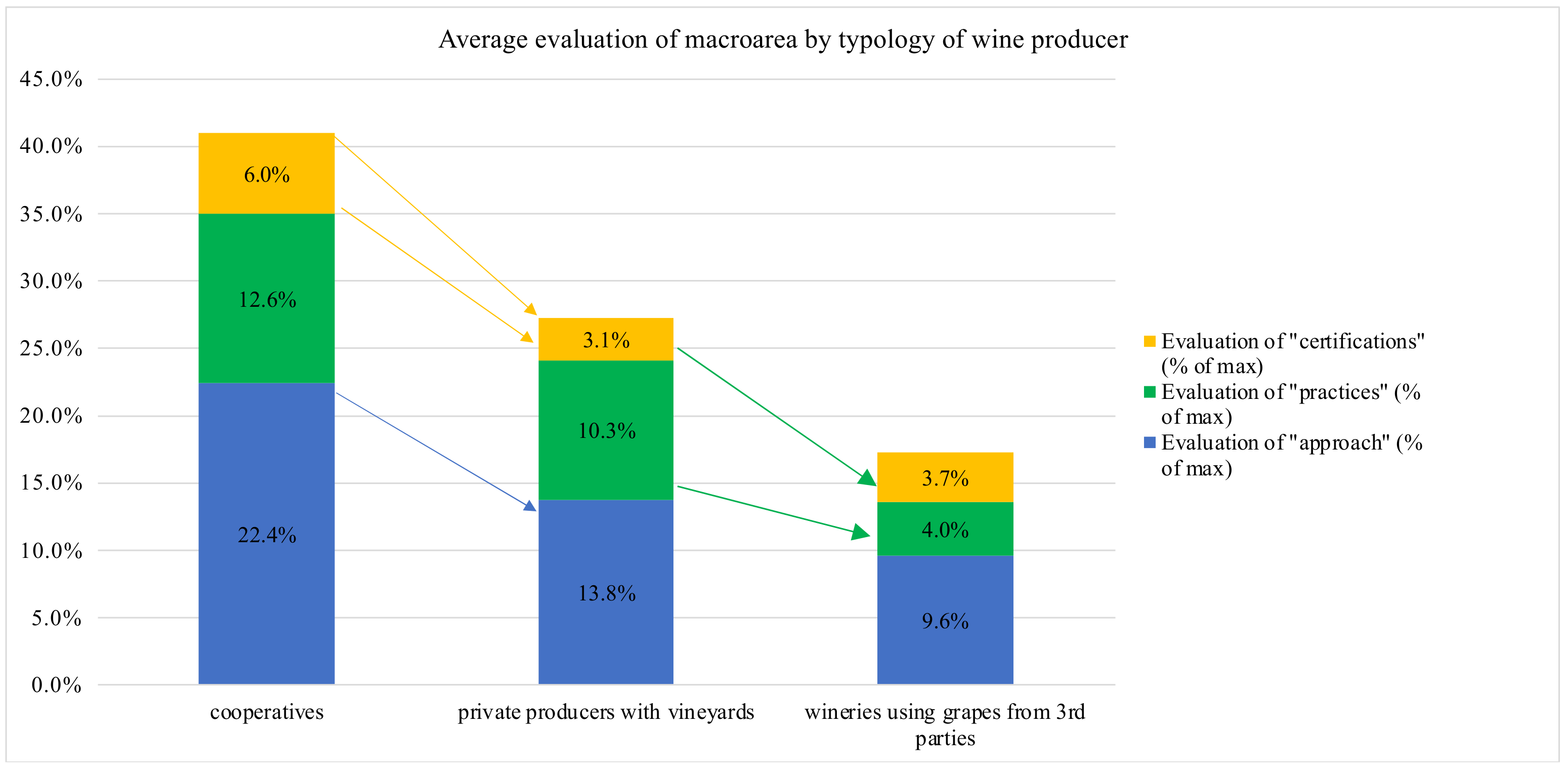

3.2. Performance by Typology of Wine Producers

- Cooperatives: 41.0%;

- Private producers with vineyards: 27.3%;

- Wineries/bottlers (using grapes from third parties): 17.3%.

- “approach” (including Indicators 1–6, 8 and 9);

- “practices” (Indicator 7);

- “certifications” (Indicator 10).

3.3. Level of Application of the Sustainability Practices in the Panel: Strengths and Weaknesses

- Quality and food safety certifications (e.g., ISO 9001, ISO 22001, BRC, IFS, SQNPI);

- Sustainability certification (e.g., EQUALITAS, VIVA).

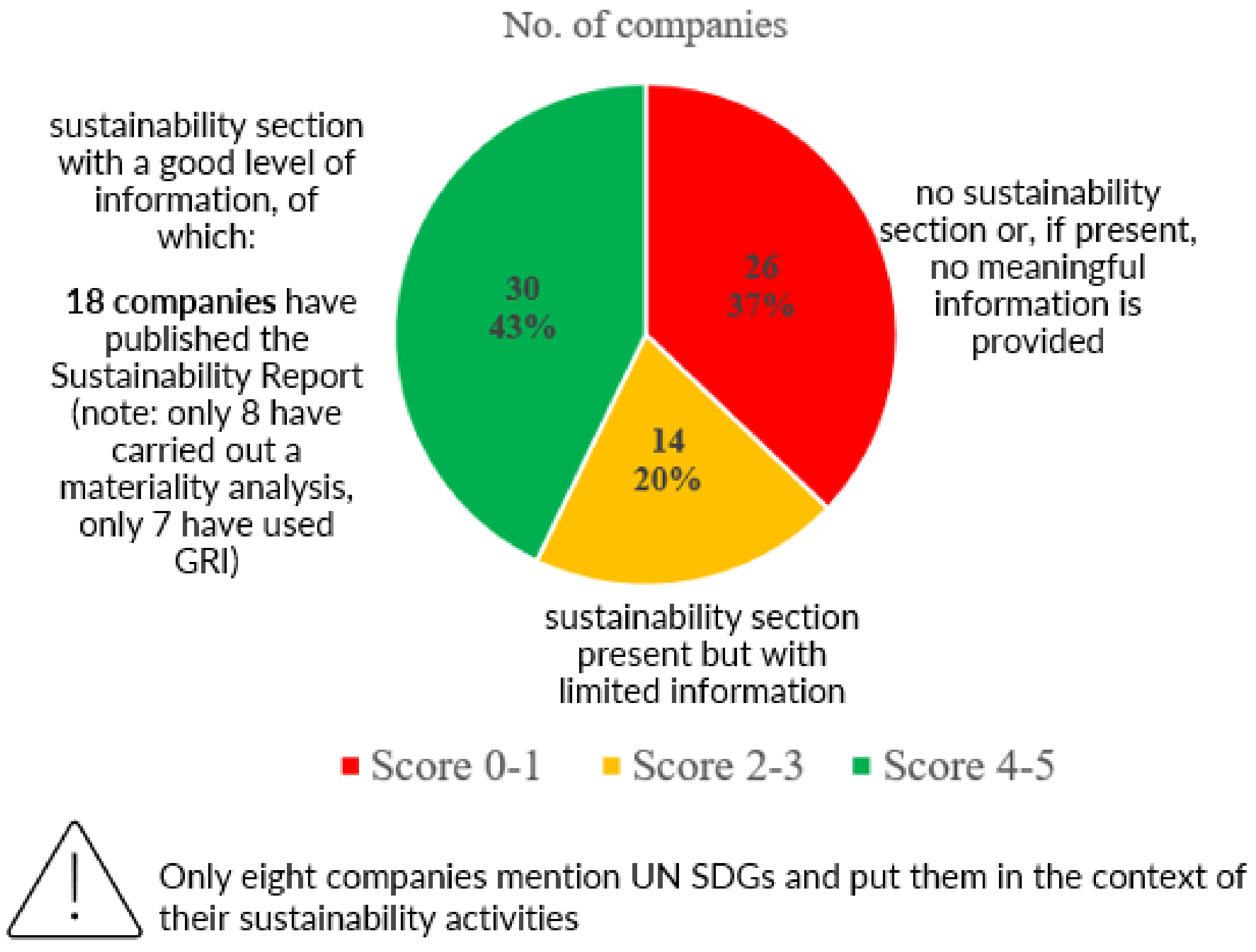

3.4. The Level of Communication

4. Conclusions

- The overall evaluation of the companies is distributed mainly in the lower part of the model, suggesting that the sector has to improve its sustainability performance. However, it must be noted that this result depends on the adopted scoring model and on how the sector communicates its sustainability efforts (see below). The overall evaluation indicates that the sustainability performance does not depend on the size of the company; moreover, cooperatives are the best performing typology.

- The strengths, i.e., the most commonly recurring practices, are the certification of quality and food safety (e.g., ISO 9001, ISO 22001, BRC, IFS, SQNPI), as well as energy and water management. Certifications are widely used: In fact, 84% of the panel has at least one certification. Meanwhile, the weaknesses, i.e., the least commonly recurring practices, are the promotion of drinking awareness and information on economic sustainability (e.g., financial statements and risk analysis). Also, materiality analysis, which is the key to sustainability planning, is a significant weakness for all typologies of wine producers.

- The wine sector shows variability in both the approaches towards sustainability and the sensitivity of stakeholders towards this topic. Additionally, it is characterized by the absence of a unique certification for sustainability.

- The Italian wine sector does not communicate effectively about its sustainability efforts: only 43% of the panel has comprehensive communication.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- I Numeri del Vino. Available online: http://www.inumeridelvino.it/2022/06/la-produzione-di-vino-in-italia-nel-2021-dati-provvisori-istat.html (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Area Studi Mediobanca. Il Settore Vinicolo in Italia. Available online: https://mglobale.promositalia.camcom.it/analisi-di-mercato/tutte-le-news/settore-vinicolo-in-italia-2023.kl (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Unione Italiana Vini. Vino in Cifre. Il Corriere Vinicolo, Anno 95, N.1, 10 Gennaio 2022. Available online: https://corrierevinicolo.unioneitalianavini.it/giornale/vino-in-cifre-2022/ (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Carrol, A.B. Corporate Social Responsibility: Evolution of a Definitional Construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latapí Agudelo, M.A.; Jóhannsdóttir, L.; Davídsdóttir, B. A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Corporate Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission of the European Communities. GREEN PAPER Promoting a European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2001:0366:FIN:EN:PDF%20 (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- World Commission on Environment and Development. In Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987.

- Tubiello, F.N.; Conchedda, G. Emissions due to Agriculture: Global, Regional and Country Trends 2000–2018; FAO Food and Nutrition Paper; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Italian Ministry of Ecological Transition. VIVA Program Sustainability in the Italian Wine Sector. Available online: https://viticolturasostenibile.org/en/viva-program/ (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Molteni, M.M. Corporate level Strategy. Generare Valore Condiviso Nelle Imprese Multibusiness; Integrazione della CSR nella corporate strategy, McGraw-Hill Education: Milano, Italy, 2012; pp. 397–447. [Google Scholar]

- Gubelli, S.; Bramanti, V.; Giannini, F.R.; Lascari, N. Il Paradosso dell’Olio d’Oliva: Prodotto Sostenibile, Comunicazione Acerba. Available online: https://www.foodaffairs.it/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/ALTIS_Report-olio_luglio-2021_compressed.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Santini, C.; Cavicchi, A.; Casini, L. Sustainability in the wine industry: Key questions and research trends. Agric. Food Econ. 2013, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbo, C.; Lamastra, L.; Capri, E. From Environmental to Sustainability Programs: A Review of Sustainability Initiatives in the Italian Wine Sector. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2133–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessina, D.; Galli, L.E.; Santoro, S.; Facchinetti, D. Sustainability of Machinery Traffic in Vineyard. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Eusanio, M.; Tragnone, B.M.; Petti, L. From Social Accountability 8000 (SA8000) to Social Organisational Life Cycle Assessment (SO-LCA): An Evaluation of the Working Conditions of an Italian Wine-Producing Supply Chain. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visentin, F.; Vallerani, F. A Countryside to Sip: Venice Inland and the Prosecco’s Uneasy Relationship with Wine Tourism and Rural Exploitation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambon, I.; Colantoni, A.; Cecchini, M.; Mosconi, E.M. Rethinking Sustainability within the Viticulture Realities Integrating Economy, Landscape and Energy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barisan, L.; Lucchetta, M.; Bolzonella, C.; Boatto, V. How Does Carbon Footprint Create Shared Values in the Wine Industry? Empirical Evidence from Prosecco Superiore PDO’s Wine District. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzol, L.; Luzzani, G.; Criscione, P.; Barro, L.; Bagnoli, C.; Capri, E. The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Wine Industry: The Case Study of Veneto and Friuli Venezia Giulia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Area Studi Mediobanca; Sace (gruppo cdp); Ipsos. Report Vino e Spirits: Le Sfide di Un’eccellenza Italiana—Il Cambiamento Strutturale delle Imprese e dei Consumi Nello Scenario Post Pandemico. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/2021-07/Vino%20e%20Spirits_Report%20Integrale.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Sogari, G.; Pucci, T.; Aquilani, B.; Zanni, L. Millennial Generation and Environmental Sustainability: The Role of Social Media in the Consumer Purchasing Behavior for Wine. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indagine sul Settore Vinicolo 2020; Area Studi Mediobanca: Milano, Italy, 2020.

- Equalitas. The Equalitas-Sustainable Wine Standard. Available online: https://www.equalitas.it/en/the-standard/ (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Global Sustainability Standards Board. The Global Standards for Sustainability Impacts. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/ (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- ISO 9001. Available online: https://www.iso.org/iso-9001-quality-management.html (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- ISO 22001. Available online: https://www.qualios.com/en/iso-22001.html (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- ISO 14001. Available online: https://www.iso.org/iso-14001-environmental-management.html (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- ISO 50001. Available online: https://www.iso.org/iso-50001-energy-management.html (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- ISO 45001. Available online: https://www.iso.org/iso-45001-occupational-health-and-safety.html (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- OHSAS 18001. Available online: https://www.bsigroup.com/en-HK/BS-OHSAS-18001-Occupational-Health-and-Safety/ (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- SA 8000. Available online: https://sa-intl.org/programs/sa8000/ (accessed on 18 June 2023).

| Cooperatives | Private Producers | Wineries | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weaknesses | Materiality analysis, references to UN SDGs and use of GRI standards | Materiality analysis, references to UN SDGs and use of GRI standards | Materiality analysis, references to UN SDGs and use of GRI standards |

| Health and safety certification | Research and development | ||

| Drinking awareness | Economic sustainability (risk analysis, publication of economic/financial data) | ||

| Economic sustainability (risk analysis, publication of economic/financial data) | Themes relevant to the communities (e.g., charity, territory promotion) | ||

| Promotion of sustainability practices among suppliers | Biodiversity | ||

| Promotion of sustainability practices among suppliers | |||

| Human resources | |||

| Circular economy | |||

| Improvement areas | Biodiversity | Policies | Annual sustainability report |

| Drinking awareness | Quality and food safety and respective certifications |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bertorelli, S.; Gubelli, S.; Bramanti, V.; Capri, E.; Lamastra, L. How Does the Wine Sector Perform and Communicate Sustainability? The Italian Case. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12700. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712700

Bertorelli S, Gubelli S, Bramanti V, Capri E, Lamastra L. How Does the Wine Sector Perform and Communicate Sustainability? The Italian Case. Sustainability. 2023; 15(17):12700. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712700

Chicago/Turabian StyleBertorelli, Sara, Stella Gubelli, Valentina Bramanti, Ettore Capri, and Lucrezia Lamastra. 2023. "How Does the Wine Sector Perform and Communicate Sustainability? The Italian Case" Sustainability 15, no. 17: 12700. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712700

APA StyleBertorelli, S., Gubelli, S., Bramanti, V., Capri, E., & Lamastra, L. (2023). How Does the Wine Sector Perform and Communicate Sustainability? The Italian Case. Sustainability, 15(17), 12700. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712700