Unraveling On-Farm Wheat Loss in Fars Province, Iran: A Qualitative Analysis and Exploration of Potential Solutions with Emphasis on Agricultural Cooperatives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Interviews

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

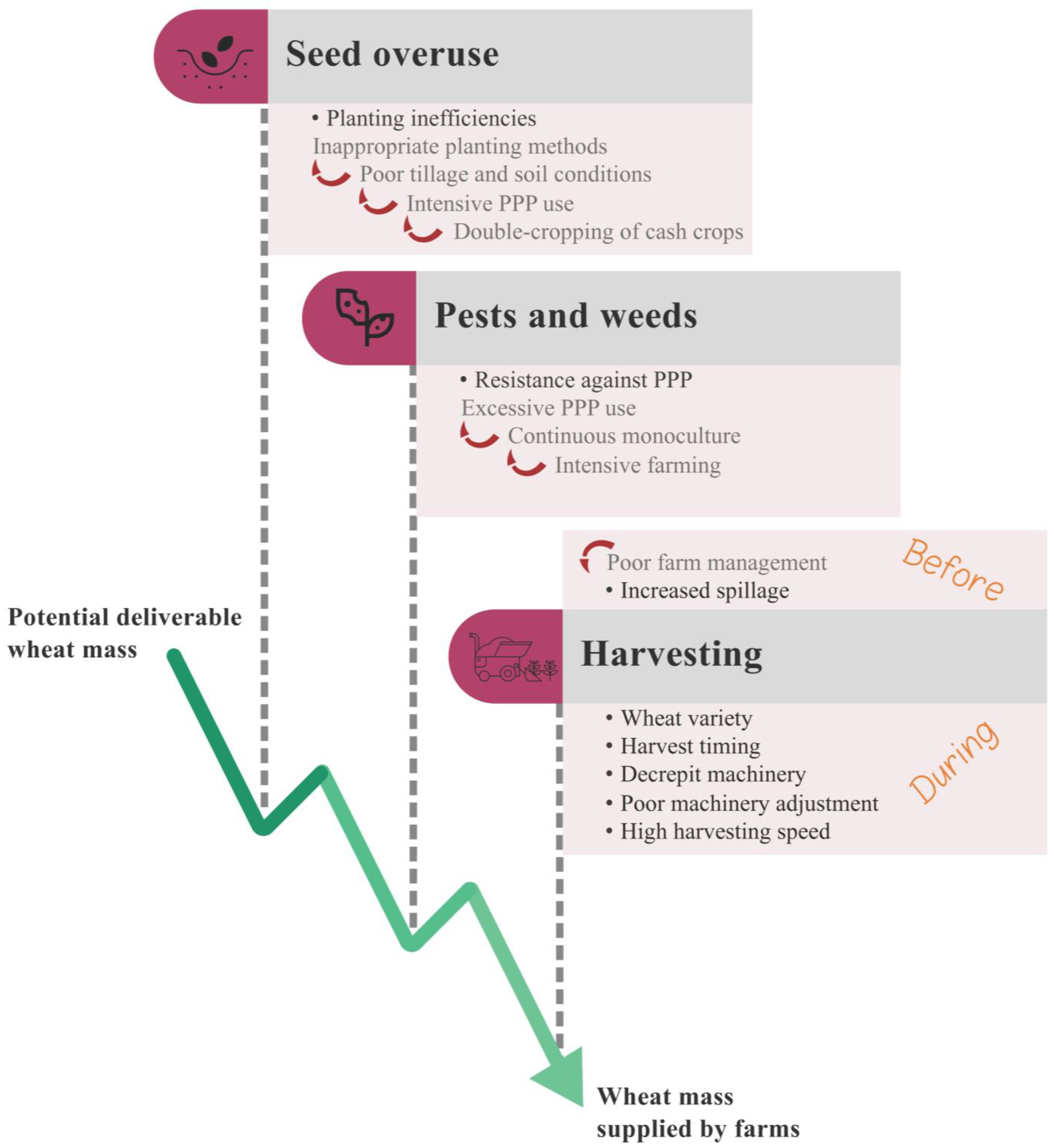

3.1. Loss due to Excessive Seed Use

“A part of the wheat loss is due to excessive seed use.”(Agri. Mins. Officer)

“Theoretically, only about 120–140 kg of seed is needed for wheat cultivation. But farmers have to sow 300 kg of seeds to succeed.”(GCCS inspector)

“I sow more than 300 kg seeds per ha, sometimes even more than 400 kg.”(Farmer 1)

“I plant 320–350 kg seeds per ha.”(Farmer 5)

“I planted about 240 kg per ha. I did not have a specific reason for choosing this number. I would say 240 kg was enough; one would argue 300 or more needs to be planted based on another reasoning. There is an old saying: the lands in this region perform well regardless of which and how much seed you plant.”(Farmer 3)

“It is very difficult to introduce a new thing to the farmers. They would certainly not accept implementing something new unless all others try that and assure them that it would work.”(Seed Producer)

“I am known as a pioneer farmer. Yet, I do not plant less than 350 kg seeds per ha, regardless of how much they [the AREEO experts] insist…. I say if we spend more money per ha, my mind would be at ease that we would harvest five to six tonnes per ha. We may harvest the same amount if we seed 100 kg per ha. But we would be worried all the time as to whether it works or not.”(Farmer 1)

“We had around 200 kg of seeds of a new variety. We were asked to test these seeds for wheat cultivation in Fars province. The requirement was to use no more than 25 kg of seeds per ha. We planted 25 kg seeds per ha using an experimental seeder. How much do you think the yield was? More than seven tonnes per ha. However, the cultivation was highly controlled in terms of pests and weeds.”(Seed Producer)

“I heard a rumor that someone sowed 60 kg seeds per ha in [name of a region]. After that, I planted less than 300 kg per ha. The AREEO experts evaluated the tillering in my field as moderate. This means my wheat was grown less than my typical performance. Imagine how bad the performance could have been if I had sowed only 100 kg seeds per ha.”(Farmer 1)

“In this region, maybe only up to 30% of farmers use drill seeders, while more than 60% use centrifugal broadcast machines and a small minority who have small farms do the traditional manual seed spreading.”(Co-op CEO)

“We tillage the land, plant the seed either with a centrifugal broadcast planting machine (normally around 300–350 kg per ha) or manually (around 320 kg per ha) and run a disk tiller.”(Farmer 4)

“The seeds will grow with minimum precipitation when you use a proper planting machinery.”(Farmer 3)

“An issue in this region is that most of the lands are also used for rice cultivation, which makes the land unsuitable for a drill seeder. The land will have many soil clumps after rice cultivation which cannot be broken entirely by tillage. Therefore, a drill seeder cannot operate well on such lands.”(Co-op CEO)

“It’s a matter of work speed. We can get the job done in two hours using a broadcast seeding machine.”(Seed Producer)

“Some farmers use drill seeding machines. Others do not believe that using such machinery is economically sound. A drill seeder works 5 ha per day, 7 ha at best. Farmers who cultivate two crops in one season want to plant 30 ha of land in two days. Or rain is forecasted, and they need to plant their seeds as soon as possible. So, they use a broadcast seeder and run a disk tiller afterward.”(Farmer 2)

“The wheat seed in temperate areas such as Shiraz [the capital of Fars province] and soundings should be embedded in a depth of 2 to 3 cm. In colder areas, it is said that they grow better when seeded 7 to 8 cm deep to avoid frost. When wheat sprouts, its coleoptile has to reach the surface. Once the coleoptile reaches the surface, the plant starts its growth. If you imbed the seed 15 cm deep, the coleoptile will dry up after growing 4 to 5 cm.”(Seed Producer)

“When I dug the soil a bit, I could see the seeds sprouted but did not grow enough to come out of the soil and were dried up underneath the surface.”(Farmer 3)

“Parts of the seeds remain on the land surface, and parts go too deep and cannot grow. That’s why even knowledgeable farmers fear planting a low amount of seeds per ha.”(Seed Producer)

“The disk tiller is strong. It places about a third of the seeds too deep. The other third stays on the surface and will be eaten by insects and animals. Only one-third will be planted in the optimal depth. This means out of 400 kg seeds, only 130 kg is optimally planted.”(Farmer 2)

“A huge part of seed loss is due to improper tillage and soil conditions.”(GCCS Inspector)

“The first reason [for excessive seed use] is the inability in optimal land preparation, mainly due to the unavailability of proper tillage equipment.”(Farmer 1)

“Those who seed 100 kg per ha prepare the farm properly to embed the seed in a certain depth so all the 100 kg can grow… Whatever I do, my land does not reach the optimal condition for growing 100 kg per ha. I run the rototiller once and the disk tiller three times, and still, the sowing is highly inefficient.”(Farmer 1)

“The common crop rotation in this region is usually maize and wheat. In the regions where more water is accessible, farmers cultivate rice too.”(GCCS Inspector)

“Crop rotation in this region is commonly rice and wheat or maize and wheat. Some farmers would cultivate tomatoes every three to four years too.”(Co-op CEO)

“Farmers cultivate maize right away after harvesting wheat. For example, they cultivate a maize variety with a growth period of about only three months.”(Farmer 1)

“We normally cultivate rice after wheat.”(Farmer 4)

“Depending on when wheat is harvested, farmers start transplanting rice seedlings between June and July and harvest rice from mid-September until mid-October.”(Co-op CEO)

“Another issue is the farm size. The farms are not large enough to be divided into different parts for cultivation and fallow. You see cases that five siblings inherited 10 ha, which they divided into five two-ha fields. They fail to work together, and there is not enough space to leave fallow… As long as the farmers have enough water, they don’t leave their farms fallow.”(Co-op CEO)

“The lands are divided among multiple farmers. Each person is trying to make maximum profit, so farming is more intensified. Farmers look for varieties with short growth periods. The new varieties need one or two irrigations less than the old ones, although their yield is slightly less. But it is economically justifiable because of timing.”(Farmer 1)

“To harvest 10 tonnes per ha, farmers need to irrigate several times (up to seven times) and use a lot of chemical fertilizers and pesticides.”(Farmer 4)

“In the past, one run of a disk tiller per year was enough. Now we need to run a heavy disk tiller to break the soil lumps, which are rigid due to the overuse of fertilizers. The soil has lost all of its organic matter. That’s why the farmer has to run the disk tiller three times after plowing. Then the farmer has to run a leveler.”(Farmer 2)

“If we cultivate rice before wheat, we need more wheat seeds (more than 350 kg per ha). Because rice cultivation takes up many nutrients in the soil and also leaves too humid of land behind. Therefore, the tillage cannot be performed properly, and more seeds are needed.”(Farmer 4)

“The fields in this region [the Dorodzan area in the north of Fars province] are used for rice production. Almost all farmers use basin irrigation for wheat cultivation.”(Co-op CEO)

“Farmers use Urea fertilizer excessively. Urea fertilizer makes the land rigid. Overuse of Urea fertilizer is one of the main reasons that we cannot tillage the lands optimally.”(Farmer 1)

3.2. Loss due to Weeds and Pests

“A part of the loss is due to insect infestation.”(GCCS Inspector)

“Pests are also a major cause for losing parts or entire wheat crops.”(Farmer 3)

“We are facing pests and weeds that did not exist, let’s say, 30 years ago. I have been cultivating wheat for more than 40 years. The production costs for wheat cultivation were around 22% of the gross income, although the yield was lower than now. The costs are now more than 50% of the wheat cultivation. The costs of purchasing pesticides are very considerable.”(Farmer 1)

“We need to use a new pesticide every year because the pests develop resistance to the old ones.”(Farmer 1)

“Not all farmers afford to purchase effective pesticides. They need to buy Indian pesticides, which have to be applied three or four times to eliminate the pests.”(Farmer 2)

3.3. Loss due to Harvesting

“Wheat is lost on a farm before or during harvest.”(GCCS Inspector)

“The loss also occurs right before the plant is ready for harvesting.”(Farmer 3)

“The majority of loss occurs during harvesting on the farm.”(Co-op CEO)

“Wheat is harvested [in Fars] mainly using a combine harvester, which is a major point of loss.”(Farmer 1)

“Wheat loss before harvest is mainly due to wind or birds.”(GCCS Inspector)

“If plants do not receive enough water at a critical time, about one month before harvesting, the wind will dry out the wheat head, which would cause loss. Leveling the land properly before cultivation would prevent this loss. If the land is uneven, the plants that are placed higher than others do not receive enough water and would dry out.”(Farmer 3)

“The pre-harvest loss is sometimes higher for some wheat varieties compared to the others.”(GCCS Inspector)

- Wheat variety: different varieties of wheat can impact loss during harvest.

- Harvest timing: harvesting too late can increase shattering.

- Decrepit and misaligned machinery: outdated or poorly maintained machinery can result in a higher wheat loss.

- Incorrect adjustment of the machinery: improper settings in the combine harvester can cause the loss of wheat.

- Running the combine harvester too fast: operating the combine harvester at a high speed can result in a further loss of wheat.

“Some varieties have a higher loss during harvest. So, part of the harvest loss depends on the wheat variety.”(Seed Producer)

“Reasons, such as late harvesting, can also cause loss.”(Co-op CEO)

“The demand for combine harvesters is too high during the harvest period and it is difficult to find one at the best time for harvesting my crops.”(Seed Producer)

“New machines have a lower loss indeed, but only when they are well-tuned.”(Seed Producer)

“Another reason for loss during harvesting is an incorrect adjustment or technical issues of a combine harvester, which is the most significant reason.”(Farmer 3)

“When a combine harvester operator runs the machine too fast on the land, the loss will be higher. The operator tends to finish the job as soon as possible, particularly when paid per hectare.”(Seed Producer)

“[Harvest loss happens] mainly due to harvesting too quickly. Especially the new combine harvesters have air conditioner and the operator is sitting in a cabin and does not care how much is lost.”(Farmer 5)

“Combine harvesters are often operated incorrectly, resulting in a high amount of loss that is due to operators’ lack of skill or experience.”(GCCS Inspector)

“Another reason for harvesting loss is the lack of skilled and trained combine operators. Skilled operators demand high wages because it is a difficult job.”(Co-op CEO)

“The combine operators mostly get paid either per hour or per hectare…. [grain loss] is not important for them at all. They just want to get the job done as soon as possible.”(Co-op CEO)

“The more the farmers supervise the harvest, the more they can prevent loss.”(Seed Producer)

“Harvesting takes more time on a large farm. A large-scale farmer can supervise the process and instruct the combine operator to make necessary adjustments or change the speed if they observe that the yield is insufficient or if the first batch delivered to the purchasing center is evaluated as poor [in terms of impurity and broken grains]. But harvesting on a small farm may be completed in one run and there is no room for correction…. I own a large farm. I can afford to hire a supervisor. But farmers who own smaller farms, such as those with only 10 or 15 hectares, may not have the necessary knowledge to supervise harvesting or may not be able to afford a supervisor. It takes four to five days to harvest my farm. Their [small-holder farmer] entire farm will be harvested quickly. They notice that the loss is high when their entire yield has already been harvested, and the damage is done.”(Farmer 1)

“In some regions, combine operators work for a percentage of the income. Even those who work on commission don’t care much about loss.”(Co-op CEO)

“Sometimes, the combine owner does not charge the farmer for harvesting. Instead, the combine owner collects the straws to sell as forage. In those cases, the combine operator may adjust the combine header lower to collect more biomass and make more profit, which leads to more wheat loss and impurity content in the yield.”(Farmer 4)

“Unfortunately, dilapidated harvesting machinery causes enormous loss. For example, 60–70% of our harvesting machines are 50–60 years old.”(Co-op CEO)

“Some owners of combine harvesters would rather keep their machines running all the time to maximize their profit and would skip the necessary maintenance. As a result, a considerable amount of wheat is lost due to technical problems with harvesting machinery.”(Farmer 3)

“Most farmers [in Fars province] are small-holder farmers and don’t have a good financial situation.”(Seed Producer)

3.4. Reliability of the Results

3.5. The role of Agricultural Cooperatives in Reducing On-Farm Loss

“Their [small-holder farmers’] farm areas are small, which hinders mechanization in the field. Most of these small-holder farmers cannot reach an agreement to merge their lands for easier mechanization.”(Seed Producer)

“The new combine harvesters are designed for large farms; as there are many small farms, it does not make sense to use them.”(Co-op CEO)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mesterházy, Á.; Oláh, J.; Popp, J. Losses in the Grain Supply Chain: Causes and Solutions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global Food Losses and Food Waste—Extent, Causes and Prevention; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2011.

- FAO. Food Wastage Footprint—Impacts on Natural Resources—Summary Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013.

- FAO. Food Loss Analysis for Grapes Value Chains in Egypt; FAO: Cairo, Egypt, 2021.

- FAO. Food Loss Analysis: Causes and Solutions, Case Study on the Maize Value Chain in the Republic of Malawi; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018.

- FAO. Food Loss Analysis: Causes and Solutions Case Study on the Chickpea Value Chain in the Republic of India; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018.

- FAO. Analysis of Food Losses: Causes and Solutions—Case Studies of Maize and Rice in the Democratic Republic of Congo; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. (In French)

- FAO. Food Loss Analysis: Causes and Solutions Case Study on the Cassava Value Chain in the Republic of Guyana; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018.

- Beausang, C.; Hall, C.; Toma, L. Food Waste and Losses in Primary Production: Qualitative Insights from Horticulture. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 126, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, A.; Sánchez, M.V.; Torero, M.; Vos, R. Reducing Food Loss and Waste: Five Challenges for Policy and Research. Food Policy 2021, 98, 101974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duveiller, E.; Singh, R.P.; Nicol, J.M. The Challenges of Maintaining Wheat Productivity: Pests, Diseases, and Potential Epidemics. Euphytica 2007, 157, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollaway, G.J.; Evans, M.L.; Wallwork, H.; Dyson, C.B.; Mckay, A.C. Yield Loss in Cereals, Caused by Fusarium Culmorum and F. Pseudograminearum, Is Related to Fungal DNA in Soil Prior to Planting, Rainfall, and Cereal Type. Am. Phytopathol. Soc. 2013, 97, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redlingshöfer, B.; Coudurier, B.; Georget, M. Quantifying Food Loss during Primary Production and Processing in France. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Kalita, P. Reducing Postharvest Losses during Storage of Grain Crops to Strengthen Food Security in Developing Countries. Foods 2017, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, B. The Complex Picture of On-Farm Loss. In Proceedings of the Crawford Fund 2016 Annual Conference: WASTE NOT, WANT NOT—The Circular Economy to Food Security, Canberra, Australia, 2–30 August 2016; Milligan, A., Ed.; The Crawford Fund: Canberra, Australia, 2016; pp. 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Shewry, P.R.; Hey, S.J. The Contribution of Wheat to Human Diet and Health. Food Energy Secur. 2015, 4, 178–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karizaki, V.M. Ethnic and Traditional Iranian Breads: Different Types, and Historical and Cultural Aspects. J. Ethn. Foods 2017, 4, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. World Food and Agriculture—Statistical Yearbook 2022; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fortune Business Insights. Wheat Flour Market Size, Share & COVID-19 Impact Analysis, by Type (Whole and Refined), Application (Bread, Bakery Products, Noodles & Pasta, and Others), and Regional Forecast, 2021–2028; Fortune Business Insights: Maharashtra, India, 2022.

- Statistical Centre of Iran. Summary of the Agricultural Statistics—2021/2022 (1400); Statistical Centre of Iran: Tehran, Iran, 2022.

- Katzman, K. Iran Sanctions (Updated). In Iran: U.S. Relations, Foreign Policies and Sanctions; Søndergaard, D.H., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers, Incorporated: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 229–339. ISBN 978-168507060-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mesgaran, M.B.; Madani, K.; Hashemi, H.; Azadi, P. Iran’s Land Suitability for Agriculture. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ave, S.; Bridge, S. The Agriculture and Food Market in Iran; Opportunities and Challenges for Danish Companies; The Royal Danish Embassy in Tehran: Tehran. Iran, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Feili, H.; Besharat, R.; Chitsaz, M.; Abbasi, S. Impact of Policy of Purchasing Wheat on Welfare of Producers and Consumers in Iran. J. Ind. Syst. Eng. 2018, 11, 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Shahzad, B.; Tanveer, M.; Sidhu, G.P.S.; Handa, N.; Kohli, S.K.; Yadav, P.; Bali, A.S.; Parihar, R.D.; et al. Worldwide Pesticide Usage and Its Impacts on Ecosystem. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaziani, S.; Dehbozorgi, G.; Bakhshoodeh, M.; Doluschitz, R. Identifying Loss and Waste Hotspots and Data Gaps throughout the Wheat Lifecycle in the Fars Province of Iran through Value Stream Mapping. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough?: An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Filed Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VERBI Software, MAXQDA Analytics Pro 2022, 22.7.0; VERBI GmbH Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2022.

- Fielding, J.; Fielding, N.; Hughes, G. Opening up Open-Ended Survey Data Using Qualitative Software. Qual. Quant. 2012, 47, 3261–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezhman, H.; Sedaghat, M.E.; Ramtin, F.; Saadat, N. Technical Guidelines for Increasing Wheat Yield in Wheat Based System; Jihad Agriculture Fars Organization: Shiraz, Iran, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dryland Agriculture Research Institute. Zahab Durum Wheat—Suitable for Cultivation in the Dry and Cold Temperate Regions of Iran; The Ministry of Agriculture Jihad: Tehran, Iran, 2020.

- Mirzavand, J.; Jamali, M.; Moradi Talebbeigi, R. Effect of Tillage Methods and Corn Residue Management on Wheat Yield and Weed Control in Zarghan Region of Fars Province. Res. Achiev. Field Hortic. Crops 2021, 9, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi, A.; Rahmati, M.H.; Tabatabaeefar, A. Sustainable Tillage Methods for Irrigated Wheat Production in Different Regions of Iran. Soil. Tillage Res. 2009, 104, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidi-Nasab, D.; Gharineh, M.H.; Bakhshandeh, A.; Sharafizadeh, M.; Shafeienia, A. Investigation of Yield and Yield Components of Wheat in Response to Reduced Nitrogen Fertilizer and Seed Consumption under Sustainable Agriculture Conditions. Cereal Res. 2016, 6, 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, P.; Bruce, R.; Reynolds, C.; Milligan, G. Food Chain Inefficiency (FCI): Accounting Conversion Efficiencies Across Entire Food Supply Chains to Re-Define Food Loss and Waste. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 462676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faris, D.G.; de Pauw, R.M. Effect of Seeding Rate on Growth and Yield of Three Spring Wheat Cultivars. Field Crops Res. 1980, 3, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühling, I.; Redozubov, D.; Broll, G.; Trautz, D. Impact of Tillage, Seeding Rate and Seeding Depth on Soil Moisture and Dryland Spring Wheat Yield in Western Siberia. Soil. Tillage Res. 2017, 170, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, E.B.; Leap, J.E. A Comparison of Drill and Broadcast Methods for Establishing Cover Crops on Beds. HortScience 2014, 49, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, S.K.; Hussain, I.; Sohail, M.; Kissana, N.S.; Abbas, S.G. Effects of Different Planting Methods on Yield and Yield Components of Wheat. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2003, 2, 811–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A.; Schillinger, W.F.; Gill, K.S. Wheat Seedling Emergence from Deep Planting Depths and Its Relationship with Coleoptile Length. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, P.A.; Radford, B.J.; Thomas, G.A.; Sinclair, D.P.; Key, A.J. Effect of Tillage Practices on Wheat Performance in a Semi-Arid Environment. Soil. Tillage Res. 1994, 28, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Bellido, L.; Lopez-Bellido, R.J.; Castillo, J.E.; Lopez-Bellido, F.J. Effects of Tillage, Crop Rotation, and Nitrogen Fertilization on Wheat under Rainfed Mediterranean Conditions. Agron. J. 2000, 92, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Saharawat, Y.S.; Gathala, M.K.; Jat, A.S.; Singh, S.K.; Chaudhary, N.; Jat, M.L. Effect of Different Tillage and Seeding Methods on Energy Use Efficiency and Productivity of Wheat in the Indo-Gangetic Plains. Field Crops Res. 2013, 142, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchers, A.; Truex-Powell, E.; Wallander, S.; Nickerson, C. Multi-Cropping Practices: Recent Trends in Double-Cropping; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gikonyo, F.N.; Dong, X.; Mosongo, P.S.; Guo, K.; Liu, X. Long-Term Impacts of Different Cropping Patterns on Soil Physico-Chemical Properties and Enzyme Activities in the Low Land Plain of North China. Agronomy 2022, 12, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Liang, C.; Wang, X.; McConkey, B. Lowering Carbon Footprint of Durum Wheat by Diversifying Cropping Systems. Field Crops Res. 2011, 122, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.J.; Amundson, R.; Burke, I.C.; Yonker, C. The Effect of Climate and Cultivation on Soil Organic C and N. Biogeochemistry 2004, 67, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, H.; Lal, R. Principles of Soil Conservation and Management; Springer: Hays, KS, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-14020-8708-0. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Liu, K. Cropping Systems in Agriculture and Their Impact on Soil Health-A Review. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 23, e01118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisao, K.; Khanthavong, P.; Oudthachit, S.; Matsumoto, N.; Homma, K.; Asai, H.; Shiraiwa, T. Impacts of the Continuous Maize Cultivation on Soil Properties in Sainyabuli Province, Laos. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.Y.; Xu, M.G.; Ciren, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.L.; Sun, B.H.; Yang, X.Y. Soil Aggregation and Aggregate Associated Organic Carbon and Total Nitrogen under Long-Term Contrasting Soil Management Regimes in Loess Soil. J. Integr. Agric. 2015, 14, 2405–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosttafiz, S.B.; Rahman, M.; Rahman, M. Biotechnology: Role Of Microbes In Sustainable Agriculture and Environmental Health. Internet J. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, R. Soil Erosion and Carbon Dynamics. Soil. Tillage Res. 2005, 81, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sharma, S.N.; Prasad, R. The Effect of Seeding and Tillage Methods on Productivity of Rice–Wheat Cropping System. Soil. Tillage Res. 2001, 61, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talpur, M.A.; Changying, J.I.; Junejo, S.A.; Tagar, A.A. Impact of Rice Crop on Soil Quality and Fertility. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 19, 1287–1291. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, K.G.; Misra, A.K.; Hati, K.M.; Bandyopadhyay, K.K.; Ghosh, P.K.; Mohanty, M. Rice Residue-Management Options and Effects on Soil Properties and Crop Productivity. Food Agric. Environ. 2004, 2, 224–231. [Google Scholar]

- Lindau, C.W.; Patrick, W.H.; DeLaune, R.D. Factors Affecting Methane Production in Flooded Rice Soils. Agric. Ecosyst. Eff. Trace Gases Glob. Clim. Change 2015, 55, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.W. Soil PH and Soil Acidity. In Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 3: Chemical Methods; Soil Science Society of America and American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 2018; pp. 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, A.; Gosal, S.K. Effect of Pesticide Application on Soil Microorganisms. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2011, 57, 569–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, J.W. Soil Health and Global Sustainability: Translating Science into Practice. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2002, 88, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.A.; Gregory, P.J. Soil, Food Security and Human Health: A Review. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 2015, 66, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Effects of Seven Diversified Crop Rotations on Selected Soil Health Indicators and Wheat Productivity. Agronomy 2020, 10, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.P. Pesticides, Environment, and Food Safety. Food Energy Secur. 2017, 6, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, R.F.; Exner, M.E. Occurrence of Nitrate in Groundwater—A Review. J. Environ. Qual. 1993, 22, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.T.; Kou, C.L.; Zhang, F.S.; Christie, P. Nitrogen Balance and Groundwater Nitrate Contamination: Comparison among Three Intensive Cropping Systems on the North China Plain. Environ. Pollut. 2006, 143, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárceles Rodríguez, B.; Durán-Zuazo, V.H.; Soriano Rodríguez, M.; García-Tejero, I.F.; Gálvez Ruiz, B.; Cuadros Tavira, S. Conservation Agriculture as a Sustainable System for Soil Health: A Review. Soil. Syst. 2022, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, P.; Pellerin, S.; Seufert, V.; Nesme, T. Changes in Crop Rotations Would Impact Food Production in an Organically Farmed World. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurr, G.M.; Lu, Z.; Zheng, X.; Xu, H.; Zhu, P.; Chen, G.; Yao, X.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, Z.; Catindig, J.L.; et al. Multi-Country Evidence That Crop Diversification Promotes Ecological Intensification of Agriculture. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 16014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainard, L.D.; Navarro-Borrell, A.; Hamel, C.; Braun, K.; Hanson, K.; Gan, Y. Increasing the Frequency of Pulses in Crop Rotations Reduces Soil Fungal Diversity and Increases the Proportion of Fungal Pathotrophs in a Semiarid Agroecosystem. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 240, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, S. Species Redundancy and Ecosystem Reliability. Conserv. Biol. 1998, 12, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, H.; Fan, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Fan, J.X.; Yang, S.; Hu, L.; Leung, H.; et al. Genetic Diversity and Disease Control in Rice. Nature 2000, 406, 718–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardgett, R.D.; van der Putten, W.H. Belowground Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning. Nature 2014, 515, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron, J.L.; Marler, M.; Klironomos, J.N.; Cleveland, C.C. Soil Fungal Pathogens and the Relationship between Plant Diversity and Productivity. Ecol. Lett. 2011, 14, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Hamel, C.; Gan, Y.; Vujanovic, V. Pyrosequencing Reveals How Pulses Influence Rhizobacterial Communities with Feedback on Wheat Growth in the Semiarid Prairie. Plant Soil. 2013, 367, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.T.; Miller, P.R.; McConkey, B.G.; Zentner, R.P.; Stevenson, F.C.; McDonald, C.L. Influence of Diverse Cropping Sequences on Durum Wheat Yield and Protein in the Semiarid Northern Great Plains. Agron. J. 2003, 95, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupwayi, N.Z.; Larney, F.J.; Blackshaw, R.E.; Pearson, D.C.; Eastman, A.H. Soil Microbial Biomass and Its Relationship with Yields of Irrigated Wheat under Long-Term Conservation Management. Soil. Sci. 2018, 183, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larney, F.J.; Pearson, D.C.; Blackshaw, R.E.; Lupwayi, N.Z.; Conner, R.L. Soft White Spring Wheat Is Largely Unresponsive to Conservation Management in Irrigated Rotations with Dry Bean, Potato, and Sugar Beet. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2017, 98, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oerke, E.C. Crop Losses to Pests. J. Agric. Sci. 2006, 144, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oerke, E.C.; Dehne, H.W.; Schönbeck, F.; Weber, A. Crop Production and Crop Protection: Estimated Losses in Major Food and Cash Crops.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; ISBN 0444820957. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, P.S.; Gaunt, R.E. Modelling Systems of Disease and Yield Loss in Cereals. Agric. Syst. 1980, 6, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oerke, E.C.; Dehne, H.W. Safeguarding Production—Losses in Major Crops and the Role of Crop Protection. Crop Protection 2004, 23, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwilene, F.E.; Nwanze, K.F.; Youdeowei, A. Impact of Integrated Pest Management on Food and Horticultural Crops in Africa. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2008, 128, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisberger, D.; Nichols, V.; Liebman, M. Does Diversifying Crop Rotations Suppress Weeds? A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, M. Impact of Monocropping for Crop Pest Management: Review. Acad. Res. J. 2020, 8, 447–452. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, J.D.; Pfeiffer, R.K.; Rana, M.S. The Genetic Response of Barley to DDT and Barban and Its Significance in Crop Protection. Weed Res. 1965, 5, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busi, R.; Vila-Aiub, M.M.; Beckie, H.J.; Gaines, T.A.; Goggin, D.E.; Kaundun, S.S.; Lacoste, M.; Neve, P.; Nissen, S.J.; Norsworthy, J.K.; et al. Herbicide-Resistant Weeds: From Research and Knowledge to Future Needs. Evol. Appl. 2013, 6, 1218–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savary, S.; Ficke, A.; Aubertot, J.N.; Hollier, C. Crop Losses Due to Diseases and Their Implications for Global Food Production Losses and Food Security. Food Secur. 2012, 4, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Hussain, M.; Jabran, K.; Farooq, M.; Farooq, S.; Gašparovič, K.; Barboricova, M.; Aljuaid, B.S.; El-Shehawi, A.M.; Zuan, A.T.K. The Impact of Different Crop Rotations by Weed Management Strategies’ Interactions on Weed Infestation and Productivity of Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Agronomy 2021, 11, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebman, M.; Dyck, E. Crop Rotation and Intercropping Strategies for Weed Management. Ecol. Appl. 1993, 3, 92–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, T.; Zahir, Z.A.; Naveed, M.; Kremer, R.J. Limitations of Existing Weed Control Practices Necessitate Development of Alternative Techniques Based on Biological Approaches. Adv. Agron. 2018, 147, 239–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-Segura, V.; Grass, I.; Breustedt, G.; Rohlfs, M.; Tscharntke, T. Strip Intercropping of Wheat and Oilseed Rape Enhances Biodiversity and Biological Pest Control in a Conventionally Managed Farm Scenario. J. Appl. Ecol. 2022, 59, 1513–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Dhaka, A.K.; Pannu, R.K.; Kumar, S. Integrated Weed Management-A Strategy for Sustainable Wheat Production—A Review. Agric. Rev. 2013, 34, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegat, A.; Nilsson, A.T.S. Interaction of Preventive, Cultural, and Direct Methods for Integrated Weed Management in Winter Wheat. Agronomy 2019, 9, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Farooq, M.; Jabran, K.; Hussain, M. Impact of Different Crop Rotations and Tillage Systems on Weed Infestation and Productivity of Bread Wheat. Crop Prot. 2016, 89, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruttwell McFadyen, R.E. Biological Control of Weeds. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1998, 43, 369–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehler, L.E. Integrated Pest Management (IPM): Definition, Historical Development and Implementation, and the Other IPM. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2006, 62, 787–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esgici, R.; Sessiz, A.; Bayhan, Y. The Relationship between the Age of Combine Harvester and Grain Losses for Paddy. Mech. Agric. 2016, 62, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; He, X.; Wang, W.; Qu, Z.; Liu, Y. Study on the Technologies of Loss Reduction in Wheat Mechanization Harvesting: A Review. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, B.V.S.; Reddy, P.S.; Bidinger, F.; Blümmel, M. Crop Management Factors Influencing Yield and Quality of Crop Residues. Field Crops Res. 2003, 84, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Koning, K. Measurement of Some Parameters of Different Spring Wheat Varieties Affecting Combine Harvesting Losses. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1973, 18, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirasi, A.; Asoodar, M.A.; Samadi, M.; Kamran, E. The Evaluation of Wheat Losses Harvesting in Two Conventional Combine (John Deere 1165, 955) in Iran. Int. J. Adv. Biol. Biomed. Res. 2014, 2, 1417–1425. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, A.P.; Jackson, J.J.; Sama, M.P.; Montross, M.D. Impact of Delayed Harvest on Corn Yield and Harvest Losses. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2021, 37, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolland, M.D.A. Grain Losses Due to Delayed Harvesting of Barley and Wheat. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 1984, 24, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronga, D.; Prà, A.D.; Immovilli, A.; Ruozzi, F.; Davolio, R.; Pacchioli, M.T. Effects of Harvest Time on the Yield and Quality of Winter Wheat Hay Produced in Northern Italy. Agronomy 2020, 10, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, D.; Lindsey, A.J.; Lindsey, L.E.; Alt, D.S.; Paul, P.A.; Lindsey, A.J.; Lindsey, L.E. Early Wheat Harvest Influenced Grain Quality and Profit but Not Yield. Crop Forage Turfgrass Manag. 2019, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamabadi, Z. Measurement the Wheat Losses in Harvesting Stage. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Food Science, Organic Agriculture and Food Security; International Organization of Academic Studies, Tehran, Iran, 21 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hofman, V.; Kucera, H. Grain Harvest Losses; North Dakota State University: Fargo, ND, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul-Aziz Abbas, A. The Effect of Combine Harvester Speed, Threshing Cylinder Speed and Concave Clearance on Threshing Losses of Rice Crop. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2019, 14, 9959–9965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mokhtor, S.A.; el Pebrian, D.; Johari, N.A.A. Actual Field Speed of Rice Combine Harvester and Its Influence on Grain Loss in Malaysian Paddy Field. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2020, 19, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, O.A.; Dahab, M.H.; Musa, M.M.; Babikir, E.S.N. Influence of Combine Harvester Forward and Reel Speeds on Wheat Harvesting Losses in Gezira Scheme (Sudan). Int. J. Sci. Adv. 2021, 2, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashgari, M.; Mobli, H.; Omid, M.; Alimardani, R.; Mohtasebi, S.S. Qualitative Analysis of Wheat Grain Damage during Harvesting with John Deere Combine Harvester. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2008, 10, 201–205. [Google Scholar]

- Senkrua, A. A Review Paper on Skills Mismatch in Developed and Developing Countries. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Policy 2021, 10, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomoi, M.I.; Nawi, N.M.; Aziz, S.A.; Kassim, M.S.M. Sensing Technologies for Measuring Grain Loss during Harvest in Paddy Field: A Review. Agriengineering 2022, 4, 292–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzzante, S.; Labarta, R.; Bilton, A. Adoption of Agricultural Technology in the Developing World: A Meta-Analysis of the Empirical Literature. World Dev. 2021, 146, 105599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astill, J.; Dara, R.A.; Campbell, M.; Farber, J.M.; Fraser, E.D.G.; Sharif, S.; Yada, R.Y. Transparency in Food Supply Chains: A Review of Enabling Technology Solutions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setor, T.K.; Senyo, P.K.; Addo, A. Do Digital Payment Transactions Reduce Corruption? Evidence from Developing Countries. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 60, 101577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouedraogo, R.; Sy, A. Can Digitalization Help Deter Corruption in Africa? IMF Working Papers; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Volume 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratova, D.V.; Glyzina, M.; Muratov, D.; Kravchenko, E. Improving Combine Harvester Productivity as the Main Factor of Increasing the Economic Efficiency of Grain-Harvesting Process. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 273, 07013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsharnia, F.; Marzban, A.; Asoodar, M.; Abdeshahi, A. Preventive Maintenance Optimization of Sugarcane Harvester Machine Based on FT-Bayesian Network Reliability. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2021, 38, 722–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akay, A.E.; Sessions, J. Identifying the Factors Influencing the Cost of Mechanized Harvesting Equipment. J. Sci. Eng. 2004, 7, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Masek, J.; Novak, P.; Jasinskas, A. Evaluation of Combine Harvester Operation Costs in Different Working Conditions. In Proceedings of the 16th International Scientific Conference Engineering for Rural Development, Jelgava, Latvia, 26 May 2017; Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies: Jelgava, Latvia, 2017; Volume 16, pp. 1180–1185. [Google Scholar]

- Olt, J.; Küüt, K.; Ilves, R.; Küüt, A. Assessment of the Harvesting Costs of Different Combine Harvester Fleets. Res. Agric. Eng. 2019, 65, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovev, D.A.; Chumakova, S.V.; Goncharov, R.D. Mathematical Model of Analytical Approach of Comparative Analysis of Productivity of Agricultural Machinery When Using Visualization Technology. BIO Web Conf. 2022, 43, 02028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarancón-Andrés, E.; Santamaria-Peña, J.; Arancón-Pérez, D.; Martínez-Cámara, E.; Blanco-Fernández, J. Technical Inspections of Agricultural Machinery and Their Influence on Environmental Impact. Agronomy 2022, 12, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, E.C. Can Qualitative Research Produce Reliable Quantitative Findings? Field Methods 2001, 13, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofaer, S. Qualitative Research Methods. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2002, 14, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M. Approaches to Qualitative-Quantitative Methodological Triangulation. Nurs. Res. 1991, 40, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Transaction: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Fusch, P.I.; Ness, L.R. Are We There Yet? Data Saturation in Qualitative Research. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burjorjee, P.; Roth, B.; Nelis, Y. Land Cooperatives as a Model for Sustainable Agriculture: A Case Study in Germany; Blekinge Institute of Technology: Karlskrona, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, E.; Smith, H.; Ngcobo, P.; Dlamini, M.; Mathebula, T. Conservation Agriculture Innovation Systems Build Climate Resilience for Smallholder Farmers in South Africa. In Conservation Agriculture in Africa: Climate Smart Agricultural Development; Mkomwa, S., Kassam, A., Eds.; CABI International: Wallingford, UK, 2022; pp. 345–360. ISBN 978-1-78924-575-2. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z.; Li, S.; Du, G.; Xue, R. Linking Smallholder Farmers to the Heilongjiang Province Crop Rotation Project: Assessing the Impact on Production and Well-Being. Sustainability 2021, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, H.; Larsén, K.; Lagerkvist, C.J.; Andersson, C.; Blad, F.; Samuelsson, J.; Skargren, P. Farm Cooperation to Improve Sustainability. A J. Hum. Environ. 2005, 34, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, T.; Damodaran, A. Can Cooperatives Influence Farmer’s Decision to Adopt Organic Farming? Agri-Decision Making under Price Volatility. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 5718–5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchekote, H.; Tajouo, E.L.N.; Melachio, M.N.; Siyapdje, E.C.; Mbeng, E. Farmers’ Accessibility to Pesticides and Generalization of Farming Practices besides the Legal Framework in Northern Bafou, in the Bamboutos Mountains (West Cameroon). Sustain. Environ. 2019, 4, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttinger, S.; Doluschitz, R.; Klaus, J.; Jenane, C.; Samarakoon, N. Agricultural Development and Mechanization in 2013: A Comparative Survey at a Global Level. In Proceedings of the CECE-CEMA Summit 2013: Towards a Competitive Industrial Production for Europe, Brussels, Belgium, 16 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Doluschitz, R. Cooperation in Agriculture; University of Hohenheim: Stuttgart, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, L.A.; Madureira, L.; Dirimanova, V.; Bogusz, M.; Kania, J.; Vinohradnik, K.; Creaney, R.; Duckett, D.; Koehnen, T.; Knierim, A. New Knowledge Networks of Small-Scale Farmers in Europe’s Periphery. Land Use Policy 2017, 63, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Hendrikse, G.; Huang, Z.; Xu, X. Governance Structure of Chinese Farmer Cooperatives: Evidence from Zhejiang Province. Agribusiness 2015, 31, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xhoxhi, O.; Pedersen, S.M.; Lind, K.M. How Does the Intermediaries’ Power Affect Farmers-Intermediaries’ Trading Relationship Performance? World Dev. Perspect. 2018, 10–12, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, W.A.; Dobson, W.D. An Analysis of Alternative Financing Strategies and Equity Retirement Plans for Farm Supply Cooperatives. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1976, 58, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grashuis, J.; Ye, S.U. A Review of the Empirical Literature on Farmer Cooperatives: Performance, Ownership and Governance, Finance, and Member Attitude. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2019, 90, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, R.; Peng, Y.; Wang, W.; Fu, X. Impacts of Technology Training Provided by Agricultural Cooperatives on Farmers’ Adoption of Biopesticides in China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, F. Cooperatives’ Tax Regimes, Political Orientation of Governments and Rent Seeking. J. Politics Law. 2009, 2, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- International Cooperative Alliance. Guidance Notes to the Co-Operative Principles; International Cooperative Alliance: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bader, J. Propping up Dictators? Economic Cooperation from China and Its Impact on Authoritarian Persistence in Party and Non-Party Regimes. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 2015, 54, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, A.; Kenworthy, L. Cooperation and Political Economic Performance in Affluent Democratic Capitalism1. Am. J. Sociol. 1998, 103, 1631–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspinall, E.; Weiss, M.L. The Limits of Civil Society: Social Movements and Political Parties in Southeast Asia. In Routledge Handbook of Southeast Asian Politics; Robison, R., Ed.; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 213–228. ISBN 0415494273. [Google Scholar]

- Bregianni, C. The Rural Utopia of an Authoritarian Regime: Did Cooperative Policy Advance during Metaxas Dictatorship in 1936–1940? Hist. Agrar. 2007, 17, 327–351. [Google Scholar]

- Planas, J.; Medina-Albaladejo, F.J. The Wine Cooperatives under the Mussolini and the Franco Dictatorships. Hist. Social. 2022, 102, 143–161. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, A. Review: The Forgotten Movement: Cooperatives and Cooperative Networks in Ukraine and Imperial Russia. Harv. Ukr. Stud. 1999, 23, 129–143. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, D. Civic Associations and Authoritarian Regimes in Interwar Europe: Italy and Spain in Comparative Perspective. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2005, 70, 288–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, G.K.; Nguyen, T.Q. Civil Society and Extractive Capacity in Authoritarian Regimes: Empirical Evidence from Vietnam. Asian J. Politi. Sci. 2021, 29, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freyburg, T. Planting the Seeds of Change inside? Functional Cooperation with Authoritarian Regimes and Socialization into Democratic Governance. World Politi. Sci. Rev. 2012, 8, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Rank | Country | Wheat Production in Thousand Tonnes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | China | 134,255 |

| 2 | India | 107,590 |

| 3 | Russian Federation | 85,896 |

| 4 | USA | 49,691 |

| 5 | Canada | 35,183 |

| 6 | France | 30,144 |

| 7 | Pakistan | 25,248 |

| 8 | Ukraine | 24,912 |

| 9 | Germany | 22,172 |

| 10 | Türkiye * | 20,500 |

| 11 | Argentina | 19,777 |

| 12 | Iran | 15,000 |

| 22 | Iraq * | 6238 |

| 25 | Afghanistan * | 5185 |

| 42 | Turkmenistan * | 1320 |

| 45 | Azerbaijan * | 1819 |

| 76 | Armenia * | 132 |

| Participant ID | Role |

|---|---|

| Seed producer | The owner of a plant-breeding and seed-production company |

| Farmer 1 | A farmer with a large-sized land (over 70 ha) |

| Farmer 2 | A farmer with a small-sized land (10 ha) |

| Farmer 3 | A farmer with a small-sized land (10 ha) |

| Farmer 4 | A farmer with a small-sized land (20 ha) |

| Farmer 5 | A farmer with a small-sized land (20 ha) |

| Co-op CEO | The chief executive officer (CEO) at a local agricultural cooperative and a farmer with a medium-sized land (50 ha) |

| GCCS inspector | The technical inspector of the Grain Company and Commercial Services (GCCS) of Fars province |

| Agri. Mins. Officer | A high-ranking officer at t he Ministry of Agriculture |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghaziani, S.; Dehbozorgi, G.; Bakhshoodeh, M.; Doluschitz, R. Unraveling On-Farm Wheat Loss in Fars Province, Iran: A Qualitative Analysis and Exploration of Potential Solutions with Emphasis on Agricultural Cooperatives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12569. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612569

Ghaziani S, Dehbozorgi G, Bakhshoodeh M, Doluschitz R. Unraveling On-Farm Wheat Loss in Fars Province, Iran: A Qualitative Analysis and Exploration of Potential Solutions with Emphasis on Agricultural Cooperatives. Sustainability. 2023; 15(16):12569. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612569

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhaziani, Shahin, Gholamreza Dehbozorgi, Mohammad Bakhshoodeh, and Reiner Doluschitz. 2023. "Unraveling On-Farm Wheat Loss in Fars Province, Iran: A Qualitative Analysis and Exploration of Potential Solutions with Emphasis on Agricultural Cooperatives" Sustainability 15, no. 16: 12569. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612569

APA StyleGhaziani, S., Dehbozorgi, G., Bakhshoodeh, M., & Doluschitz, R. (2023). Unraveling On-Farm Wheat Loss in Fars Province, Iran: A Qualitative Analysis and Exploration of Potential Solutions with Emphasis on Agricultural Cooperatives. Sustainability, 15(16), 12569. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612569