Examining the Impact of Entrepreneurial Orientation on New Venture Performance in the Emerging Economy of Lebanon: A Moderated Mediation Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- How does entrepreneurial orientation impact new venture performance in Lebanon?;

- (2)

- Does transformational leadership have a moderator role between entrepreneurial orientation and new venture performance?

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO)

2.2. Opportunity Exploitation (OE)

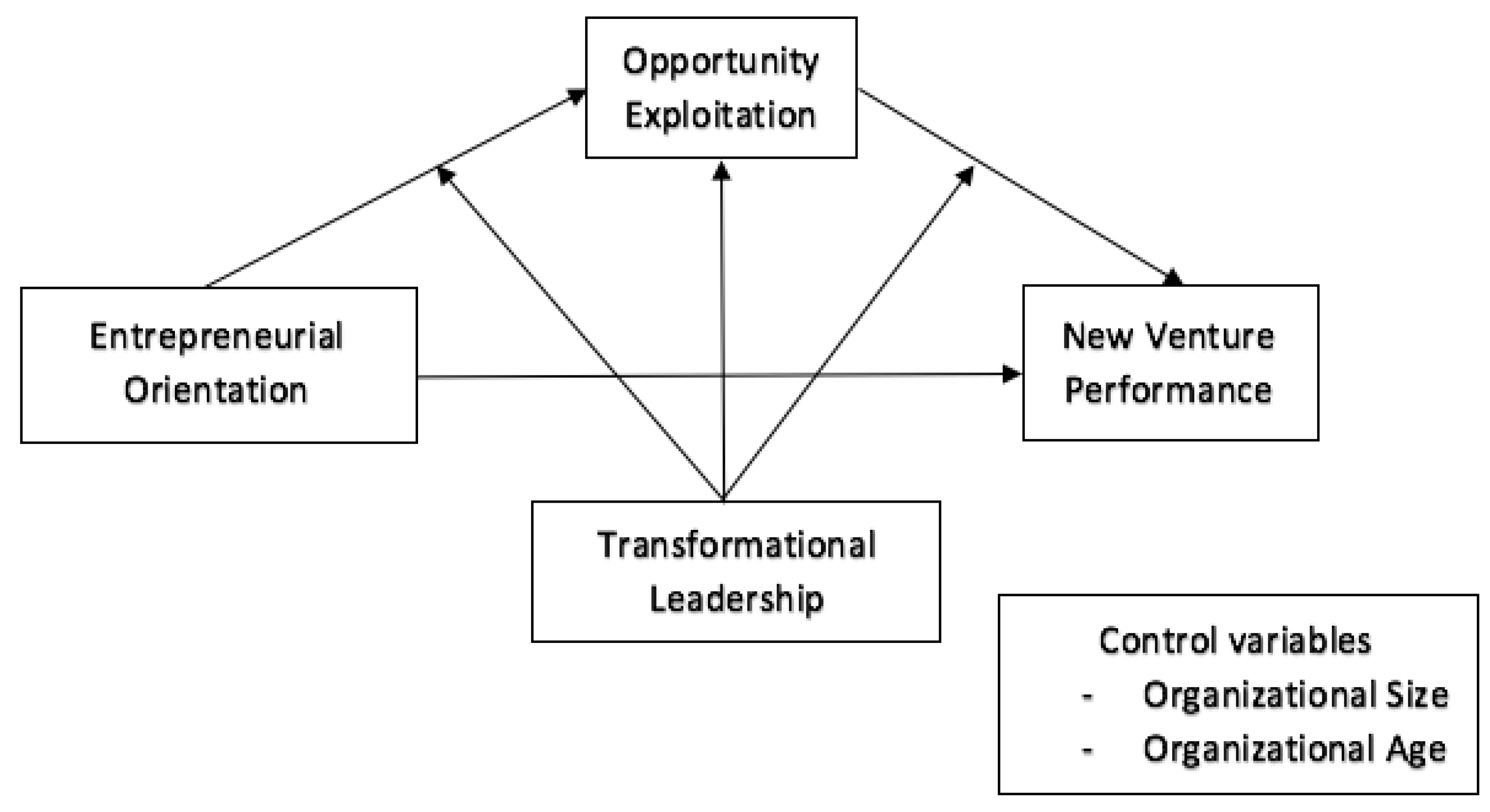

2.3. The Mediating Role of Opportunity Exploitation (OE)

2.4. The Moderating Role of Transformational Leadership (TL)

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Description

3.2. Variable Selection

3.3. Models and Methodology

3.3.1. Conceptual Model

3.3.2. Statistical Methods

4. Estimation Results

4.1. Pre-Estimation Tests

4.2. Moderated Mediation Analysis

4.2.1. Mediation Results

4.2.2. Moderation Results

4.2.3. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Concluding Remark

5.2. Policy Implications

5.3. Limitation

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, X.; Li, Y.; Su, Z.; Tao, Y.; Nguyen, B.; Xia, F. Entrepreneurial bricolage and its effects on new venture growth and adaptiveness in an emerging economy. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2020, 37, 1141–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.; Clauss, T.; Issah, W.B. Entrepreneurial orientation and new venture performance in emerging markets: The mediating role of opportunity recognition. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2022, 16, 769–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.W.; Etemad, H. SMEs and the global economy. J. Int. Manag. 2001, 7, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliansyah, Y.; Rammal, H.G.; Rose, E.L. Business Strategy & Performance in Indonesia’s Service Sector. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2016, 10, 164–182. [Google Scholar]

- Devece, C.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.E.; Palacios-Marqués, D. Coopetition as the new trend in inter-firm alliances: Literature review and research patterns. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2019, 13, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.X.; Sharma, P.; Zhan, W.; Liu, L. Demystifying the impact of CEO transformational leadership on firm performance: Interactive roles of exploratory innovation and environmental uncertainty. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, R.; Adonisi, M. Antecedents of corporate entrepreneurship. S. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 43, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lafuente, E.; Szerb, L.; Acs, Z.J. Country level efficiency and national systems of entrepreneurship: A data envelopment analysis approach. J. Technol. Transf. 2016, 41, 1260–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aljanabi, A.R.A. The mediating role of absorptive capacity on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and technological innovation capabilities. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 818–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasdani, K.P.; Mathew, M. Potential for opportunity recognition: Differentiating entrepreneurs. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2014, 23, 336–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Kacmar, K.M.; Busenitz, L.W. Entrepreneurial alertness in the pursuit of new opportunities. J. Bus. Ventur. 2012, 27, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoai, T.T.; Hung, B.Q.; Nguyen, N.P. The impact of internal control systems on the intensity of innovation and organizational performance of public sector organizations in Vietnam: The moderating role of transformational leadership. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Shepherd, D. Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: A configurational approach. J. Bus. Ventur. 2005, 20, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strateg. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S.A.; Busenitz, L.W. The entrepreneurship of resource-based theory. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 755–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Hughes, M.; Hu, Q. Entrepreneurial orientation and new venture resource acquisition: Why context matters. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2021, 38, 1369–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, C.M.; McDougall, P.P.; Covin, J.G.; Dalton, D.R. Governance and strategic leadership in entrepreneurial firms. J. Manag. 2002, 28, 387–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.H.; Ab Aziz, K. The dynamics between entrepreneurial orientation, transformational leadership, and intrapreneurial intention in Iranian R&D sector. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 769–792. [Google Scholar]

- Lechner, C.; Gudmundsson, S.V. Entrepreneurial orientation, firm strategy and small firm performance. Int. Small Bus. J. 2014, 32, 36–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouguerra, A.; Hughes, M.; Cakir, M.S.; Tatoglu, E. Linking entrepreneurial orientation to environmental collaboration: A stakeholder theory and evidence from multinational companies in an emerging market. Br. J. Manag. 2023, 34, 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J. The sustainability of the entrepreneurial orientation—Performance relationship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1999, 24, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardi, Y.; Susanto, P.; Abror, A.; Abdullah, N.L. Impact of entrepreneurial proclivity on firm performance: The role of market and technology turbulence. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Hum 2018, 26, 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Kozubíková, L.; Sopková, G.; Krajčík, V.; Tyll, L. Differences in innovativeness, proactiveness and competitive aggressiveness in relation to entrepreneurial motives. J. Int. Stud. 2017, 10, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathafena, R.B.; Msimango-Galawe, J. Entrepreneurial orientation, market orientation and opportunity exploitation in driving business performance: Moderating effect of interfunctional coordination. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Li, L.; Che, M. Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The mediating and moderating effects. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 2017, p. 13583. [Google Scholar]

- Kantur, D. Strategic entrepreneurship: Mediating the entrepreneurial orientation-performance link. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielnik, M.M.; Zacher, H.; Frese, M. Focus on opportunities as a mediator of the relationship between business owners’ age and venture growth. J. Bus. Ventur. 2012, 27, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, W.; Elfring, T. Entrepreneurial orientation and new venture performance: The moderating role of intra-and extraindustry social capital. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Wiklund, J.; Lumpkin, G.T.; Frese, M. Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 761–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, A.; Adomako, S.; Damoah, J.O.; Uddin, M. Risk-taking propensity, managerial network ties and firm performance in an emerging economy. J. Entrep. 2016, 25, 155–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Meyer, K.E. Alliance proactiveness and firm performance in an emerging economy. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 82, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmann, T.; Stöckmann, C.; Niemand, T.; Hensellek, S.; de Cruppe, K. A configurational approach to entrepreneurial orientation and cooperation explaining product/service innovation in digital vs. non-digital startups. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobel, A.K. Benefiting from open innovation: A multidimensional model of absorptive capacity. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2017, 34, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisón, C.; Forés, B. Knowledge absorptive capacity: New insights for its conceptualization and measurement. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javalgi, R.G.; Hall, K.D.; Cavusgil, S.T. Corporate entrepreneurship, customer-oriented selling, absorptive capacity, and international sales performance in the international B2B setting: Conceptual framework and research propositions. Int. Bus. Rev. 2014, 23, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Day, G.S. An outside-in approach to resource-based theories. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 42, 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, V.; Lahti, T.; Wincent, J. Exploration and exploitation and firm performance variability: A study of ambidexterity in entrepreneurial firms. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2016, 12, 1147–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Ellinger, A.D.; Jim Wu, Y.C. Entrepreneurial opportunity recognition: An empirical study of R&D personnel. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 248–266. [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith, J. Designing Complex Organizations; Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Covin, J.G.; Wales, W.J. The measurement of entrepreneurial orientation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 677–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, B.C.; Liang, T.W.; Meng, T.T.; Chan, B. The key success factors, distinctive capabilities, and strategic thrusts of top SMEs in Singapore. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 51, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.R.; Lévesque, M.; Shepherd, D.A. When should entrepreneurs expedite or delay opportunity exploitation? J. Bus. Ventur. 2008, 23, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoruk, E.; Jones, P. Firm-environment alignment of entrepreneurial opportunity exploitation in technology-based ventures: A configurational approach. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 61, 612–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.C. Opportunity related absorptive capacity and entrepreneurial alertness. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangus, K.; Slavec, A. The interplay of decentralization, employee involvement and absorptive capacity on firms’ innovation and business performance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 120, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, J.; Llorens, J.; Braojos, J. How information technology influences opportunity exploration and exploitation firm’s capabilities. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 508–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Wales, W.J. Crafting high-impact entrepreneurial orientation research: Some suggested guidelines. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donbesuur, F.; Boso, N.; Hultman, M. The effect of entrepreneurial orientation on new venture performance: Contingency roles of entrepreneurial actions. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 118, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dass, M.; Arnett, D.B.; Yu, X. Understanding firms’ relative strategic emphases: An entrepreneurial orientation explanation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 84, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, J.C.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr.; Shook, C.L.; Ireland, R.D. The concept of “opportunity” in entrepreneurship research: Past accomplishments and future challenges. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 40–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundqvist, S.; Kyläheiko, K.; Kuivalainen, O.; Cadogan, J.W. Kirznerian and Schumpeterian entrepreneurial-oriented behavior in turbulent export markets. Int. Mark. Rev. 2012, 29, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, M.; Santaló, J.; Silva, R. Being better vs. being different: Differentiation, competition, and pricing strategies in the Spanish hotel industry. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davcik, N.S.; Sharma, P. Impact of product differentiation, marketing investments and brand equity on pricing strategies: A brand level investigation. Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 760–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resick, C.J.; Whitman, D.S.; Weingarden, S.M.; Hiller, N.J. The bright-side and the dark-side of CEO personality: Examining core self-evaluations, narcissism, transformational leadership, and strategic influence. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang XH, F.; Kim, T.Y.; Lee, D.R. Cognitive diversity and team creativity: Effects of team intrinsic motivation and transformational leadership. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3231–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Para-González, L.; Jiménez-Jiménez, D.; Martínez-Lorente, A.R. Exploring the mediating effects between transformational leadership and organizational performance. Empl. Relat. 2018, 40, 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriopoulos, C.; Lewis, M.W. Managing innovation paradoxes: Ambidexterity lessons from leading product design companies. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donate, M.J.; de Pablo JD, S. The role of knowledge-oriented leadership in knowledge management practices and innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Waarden, F. Institutions and innovation: The legal environment of innovating firms. Organ. Stud. 2001, 22, 765–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, T.H.; Demircioglu, M.A.; Alsos, G.A. Intensity of innovation in public sector organizations: The role of push and pull factors. Public Adm. 2020, 98, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gupta, V.; MacMillan, I.C.; Surie, G. Entrepreneurial leadership: Developing and measuring a cross-cultural construct. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1999, 8, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, A.; Melin, L.; Nordqvist, M. Entrepreneurship as radical change in the family business: Exploring the role of cultural patterns. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2001, 14, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fındıklı, M.A.; Yozgat, U.; Rofcanin, Y. Examining organizational innovation and knowledge management capacity the central role of strategic human resources practices (SHRPs). Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 181, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Moorman, R.H.; Fetter, R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 1990, 1, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.; Kotha, S.; Lahiri, A. Changing with the times: An integrated view of identity, legitimacy, and new venture life cycles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2016, 41, 383–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, A.; Gupta, V.; Strenger, L.; Brettel, M. Entrepreneurial orientation, firm performance, and the moderating role of transformational leadership behaviors. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1069–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, D.; Tenne-Gazit, O. Transformational leadership and group interaction as climate antecedents: A social network analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brettel, M.; Heinemann, F.; Engelen, A.; Neubauer, S. Cross-functional integration of R&D, marketing, and manufacturing in radical and incremental product innovations and its effects on project effectiveness and efficiency. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2011, 28, 251–269. [Google Scholar]

- Hyder, S.; Lussier, R.N. Why businesses succeed or fail: A study on small businesses in Pakistan. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2016, 8, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulbert, B.; Gilmore, A.; Carson, D. Opportunity recognition by growing SMEs: A managerial or entrepreneurial function? J. Strateg. Mark. 2015, 23, 616–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M. Business model innovation and SMEs performance—Does competitive advantage mediate? Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2018, 22, 1850057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyiola, K.; Rjoub, H. Using conflict management in improving owners and contractors relationship quality in the construction industry: The mediation role of trust. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244019898834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naman, J.L.; Slevin, D.P. Entrepreneurship and the concept of fit: A model and empirical tests. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, Y. The relationship between psychological contract breach and employees’ counterproductive work behaviors: The mediating effect of organizational cynicism and work alienation. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ng, T.W.; Feldman, D.C.; Butts, M.M. Psychological contract breaches and employee voice behaviour: The moderating effects of changes in social relationships. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2014, 23, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Lomax, R.G. The effect of varying degrees of nonnormality in structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. 2005, 12, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Rigtering, J.C.; Hughes, M.; Hosman, V. Entrepreneurial orientation and the business performance of SMEs: A quantitative study from the Netherlands. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2012, 6, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zahra, S.A.; George, G. Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakshit, S.; Islam, N.; Mondal, S.; Paul, T. Influence of blockchain technology in SME internationalization: Evidence from high-tech SMEs in India. Technovation 2022, 115, 102518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partanen, J.; Kohtamäki, M.; Patel, P.C.; Parida, V. Supply chain ambidexterity and manufacturing SME performance: The moderating roles of network capability and strategic information flow. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 221, 107470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordman, E.R.; Tolstoy, D. The impact of opportunity connectedness on innovation in SMEs’ foreign-market relationships. Technovation 2016, 57, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tomlinson, P.R.; Fai, F.M. The nature of SME co-operation and innovation: A multi-scalar and multi-dimensional analysis. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 141, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, Z.; Zou, K. How does innovation matter for sustainable performance? Evidence from small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 153, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Yin, H.; Choi, S.; Muhammad, M. Micro-and Small-Sized Enterprises’ Sustainability-Oriented Innovation for COVID-19. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuming, Y.; Huang, W.; Xiaojing, L. Micro-and small-sized enterprises’ willingness to borrow via internet financial services during coronavirus disease 2019. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2022, 18, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Palihawadana, D.; Aykol, B.; Christodoulides, P. Effective small and medium-sized enterprise import strategy: Its drivers, moderators, and outcomes. J. Int. Mark. 2022, 30, 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Respondent Characteristics (N = 411) | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 346 | 84.18 |

| Women | 65 | 15.82 | |

| Education | Bachelor | 226 | 54.99 |

| Master | 46 | 11.19 | |

| Doctorate | 18 | 4.38 | |

| Other | 121 | 29.44 | |

| Organizational size (number of employees) | Less than 20 | 122 | 29.68 |

| 21–40 | 243 | 59.13 | |

| 41–60 | 36 | 8.76 | |

| 61–80 | 10 | 2.43 | |

| Above 80 | --- | --- | |

| Organization age (years) | Less than 2 | 209 | 50.85 |

| 2–4 | 99 | 24.09 | |

| 5–7 | 53 | 12.90 | |

| 8–10 | 42 | 10.22 | |

| Above 10 | 8 | 1.94 | |

| Work experience (years) | Less than 5 | 107 | 26.03 |

| 6–10 | 180 | 43.80 | |

| Above 10 | 124 | 30.17 | |

| Statements | Measurements |

|---|---|

| 1. The management of our organization supports the projects that are associated with risks and expectations for returns higher than average. | Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree 5 = strongly agree |

| 2. We actively observe and adopt the best practices in our sector. | |

| 3. We actively observe the new practices developed in other sectors and exploit them in our businesses. | |

| 4. We recognize early on such technological changes that may have an effect on our organization. | |

| 5. We can take on unexpected opportunities. | |

| 6. We search for new practices all the time. | |

| 7. In uncertain decision-making situations, we prefer bold actions to make sure that possibilities are exploited. |

| Statements | Measurements |

|---|---|

| Searching and identifying opportunities from changes in customer demands and preferences. | Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree 5 = strongly agree |

| Searching and identifying opportunities from changes in the economic environment. | |

| Searching and identifying opportunities from changes in the political environment. | |

| Searching and identifying opportunities from changes in the technological environment. | |

| Searching and identifying opportunities from changes in the regulatory environment. |

| Statements | Measurements |

|---|---|

| My leader clearly articulates his/her vision of the future. | Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree 5 = strongly agree |

| My leader leads by setting a good example. | |

| My leader challenges me to think about old problems in new ways. | |

| My leader says things that make employees proud to be part of the organization. | |

| My leader has a clear sense of where our organization should be in five years. |

| Questions | Measurements |

|---|---|

| 1. Return on investment | Likert scale: 1 = extremely declined 5 = extremely improved |

| 2. Return on assets | |

| 3. Return on equity | |

| 4. Sale growth | |

| 5. Employees satisfaction | |

| 6. Employee loyalty |

| Construct | Items | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted | Distribution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skewness | Kurtosis | ||||||

| Entrepreneurial Orientation | E01 | 0.802 | 0.895 | 0.914 | 0.654 | −0.109 | 0.299 |

| E02 | 0.822 | −0.282 | −0.263 | ||||

| E03 | 0.892 | −0.254 | −0.275 | ||||

| E04 | 0.799 | −0.231 | −0.922 | ||||

| E05 | 0.811 | −0.365 | 0.401 | ||||

| E06 | 0.692 | −0.211 | −1.301 | ||||

| E07 | 0.628 | −0.331 | −0.882 | ||||

| E08 | --- | ||||||

| E09 | --- | ||||||

| Opportunity Exploitation | OE1 | 0.908 | 0.901 | 0.902 | 0.693 | −0.509 | 0.067 |

| OE2 | 0.852 | −0.341 | −0.099 | ||||

| OE3 | 0.824 | −0.522 | −0.081 | ||||

| OE4 | 0.843 | −0.547 | −0.221 | ||||

| OE5 | 0.601 | −0.311 | 0.109 | ||||

| Transformational Leadership | TL1 | 0.609 | 0.939 | 0.899 | 0.621 | −0.352 | −0.282 |

| TL2 | 0.625 | −0.244 | −0.338 | ||||

| TL3 | 0.823 | −0.106 | −0.339 | ||||

| TL4 | 0.842 | −0.162 | −0.609 | ||||

| TL5 | 0.879 | −0.255 | −0.506 | ||||

| NVP | NVP1 | 0.693 | 0.940 | 0.922 | 0.649 | −0.542 | −0.266 |

| NVP2 | 0.779 | −0.524 | 0.059 | ||||

| NVP3 | 0.855 | −0.407 | −0.289 | ||||

| NVP4 | 0.805 | −0.499 | −0.406 | ||||

| NVP5 | 0.829 | −0.467 | −0.298 | ||||

| NVP6 | 0.744 | −0.235 | −0.367 | ||||

| Construct | Mean | St. Dev | EO | OE | TL | NVP | OS | OA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO) | 3.940 | 0.752 | (0.809) | |||||

| Opportunity Exploitation (OE) | 3.831 | 0.739 | 0.602 ** | (0.799) | ||||

| Transformational Leadership (TL) | 1.940 | 1.086 | 0.442 ** | 0.399 ** | (0.788) | |||

| New venture performance (NVP) | 3.560 | 0.738 | 0.209 ** | 0.327 ** | 0.353 ** | (0.806) | ||

| Organizational Size (OS) | 3.092 | 0.704 | 0.553 ** | 0.593 ** | 0.478 ** | 0.489 ** | --- | |

| Organizational AGE (OA) | 3.167 | 0.723 | 0.466 ** | 0.369 ** | 0.569 ** | 0.482 ** | 0.626 ** | --- |

| Goodness of Fit | Relative/Normal Chi-Squared (CMIN/DF) | Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) | Goodness Fit Index (GFI) | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Results | 2.710 | 0.942 | 0.939 | 0.968 | 0.055 |

| Cut-off range | CMIN/DF < 3 | CFI > 0.9 | TLI > 0.9 | GFI > 0.8 | RMSEA < 0.08 |

| β | SE | t | p | Lower CI | Upper CI | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Mediator variable model | Outcome: OE | ||||||

| EO | 0.449 | 0.041 | 9.672 | 0.000 | 0.337 | 0.622 | 0.184 |

| Model 2: Outcome variable model | Outcome: NVP | ||||||

| EO | 0.282 | 0.053 | 6.322 | 0.000 | 0.122 | 0.431 | 0.202 |

| OE | 0.316 | 0.044 | 5.862 | 0.000 | 0.101 | 0.396 | |

| Bootstrap results for the indirect effects | 0.103 | 0.035 | 0.039 | 0.143 | |||

| β | SE | t | p | Lower CI | Upper CI | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Mediator variable model | Outcome: OE | ||||||

| EO | 0.231 | 0.112 | 2.401 | 0.014 | 0.052 | 0.462 | 0.225 |

| TL | 0.366 | 0.151 | 5.091 | 0.019 | 0.086 | 0.488 | |

| EO × TL | 0.241 | 0.060 | 3.251 | 0.016 | 0.099 | 0.281 | |

| Control variable: OS | 0.031 | 0.015 | 0.769 | 0.337 | −0.026 | 0.059 | |

| Control variable: OA | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.059 | 0.855 | −0.018 | 0.043 | |

| The conditional direct effect of EO on OE | |||||||

| TL (−1SD) | 0.069 | 0.079 | 1.708 | 0.000 | 0.055 | 0.207 | |

| TL (+1SD) | 0.246 | 0.058 | 3.244 | 0.001 | 0.198 | 0.359 | |

| Model 2: Mediator variable model | Outcome: NVP | ||||||

| EO | 0.239 | 0.118 | 2.653 | 0.001 | 0.064 | 0.441 | 0.188 |

| OE | 0.425 | 0.071 | 5.445 | 0.014 | 0.220 | 0.431 | |

| EO × TL | 0.249 | 0.089 | 2.458 | 0.017 | 0.107 | 0.251 | |

| Control variable: OZ | 0.019 | 0.011 | 0.976 | 0.422 | −0.088 | 0.054 | |

| Control variable: OA | 0.070 | 0.006 | 1.361 | 0.143 | −0.049 | 0.084 | |

| The conditional direct effect of EO on NVP | |||||||

| TL (−1SD) | 0.157 | 0.071 | 1.823 | 0.015 | 0.086 | 0.374 | |

| TL (+1 SD) | 0.512 | 0.088 | 4.113 | 0.000 | 0.238 | 0.611 | |

| Bootstrap results for indirect effect (via OE) | |||||||

| Index of moderated mediation | 0.041 | 0.011 | 0.028 | 0.052 | |||

| The conditional indirect effect of EO on NVP (via OE) | |||||||

| TL (-1SD) | 0.161 | 0.042 | 1.729 | 0.010 | 0.061 | 0.286 | |

| TL (+1SD) | 0.248 | 0.049 | 2.996 | 0.000 | 0.199 | 0.362 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saleh, A.M.; Athari, S.A. Examining the Impact of Entrepreneurial Orientation on New Venture Performance in the Emerging Economy of Lebanon: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11982. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511982

Saleh AM, Athari SA. Examining the Impact of Entrepreneurial Orientation on New Venture Performance in the Emerging Economy of Lebanon: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11982. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511982

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaleh, Ahmad Mohammad, and Seyed Alireza Athari. 2023. "Examining the Impact of Entrepreneurial Orientation on New Venture Performance in the Emerging Economy of Lebanon: A Moderated Mediation Analysis" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11982. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511982

APA StyleSaleh, A. M., & Athari, S. A. (2023). Examining the Impact of Entrepreneurial Orientation on New Venture Performance in the Emerging Economy of Lebanon: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Sustainability, 15(15), 11982. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511982