Development and Validation of the Decent Work for Inclusive and Sustainable Future Construction Scale in Italy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Construct of Decent Work

1.2. Decent Work in the Life Design Paradigm

1.3. Instruments to Assess Decent Work

1.4. Decent Work, Career Adaptability, and Tendency toward a Social and Equitable Socio-Economic Vision in Career Activities

1.5. The Present Research

2. Study 1: Item Development and EFA

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Item Development

2.1.2. Participants and Procedure

2.1.3. Measures

2.1.4. Data Analysis

2.1.5. Results

3. Study 2: CFA

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants and Procedure

3.1.2. Measures

3.1.3. Data Analysis

3.1.4. Results

4. Study 3: Concurrent Validity

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Participants and Procedure

4.1.2. Measures

4.1.3. Data Analysis

4.1.4. Results

5. Study 4: Gender Invariance

5.1. Method

5.1.1. Participants and Procedure

5.1.2. Measures

5.1.3. Data Analysis

5.1.4. Results

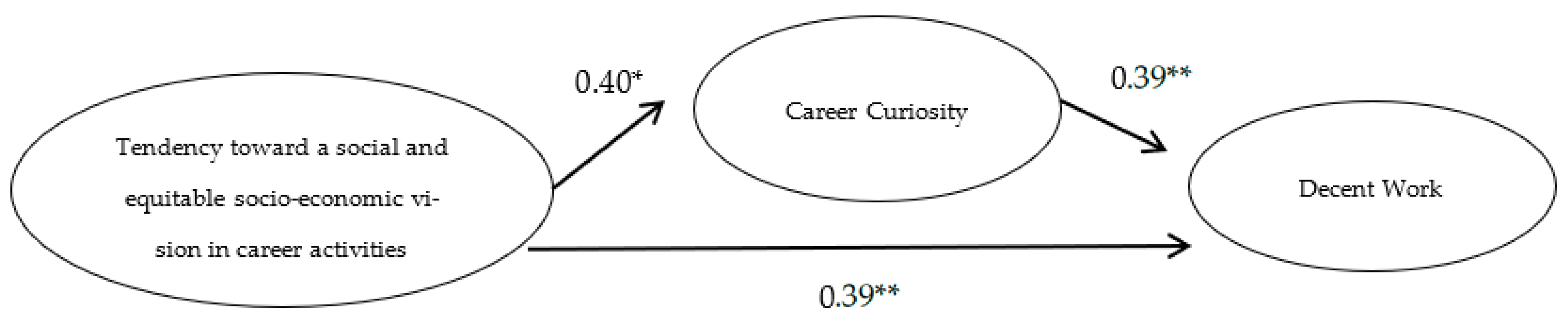

6. Structural Model

6.1. Method

6.1.1. Participants

6.1.2. Measures

6.1.3. Procedure

6.1.4. Data Analysis

6.1.5. Results

Preliminary Analysis

Structural Model

7. Discussion

8. Implications for Practice and Research

9. Limitations and Directions for Future Studies

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Instructions The following statements are about some important aspects of the work that you may have in the future. Consider them one by one and specify if and how much you agree with them, keeping in mind that 1 means “Definitely NO, this is not what I think about the work I will have in the future”. 5 means “Definitely YES, this is what I think about the work I will have in the future”. You can obviously also choose the other numbers (2, 3, 4) that represent the middle positions. |

| 1. People must not accept work in a place that does not grant everybody the right to also freely express their opinions about the work performed; |

| 2. People must accept working uniquely in places in which they are accepted for who they are (regardless of gender, age, ethnic group, religion, political orientation, etc.); |

| 3. In a workplace, the feelings and needs of workers must be a priority and considered by everyone with respect and attention; |

| 4. People must not accept working in a company that produces objects and materials that are harmful for the environment; |

| 5. Even with a high income, people must not accept working in a place where they feel they are not treated with dignity; |

| 6. People must not accept a job if a fair pay is not provided. |

References

- ILO. Decent work: Report of the Director-General. In Proceedings of the International Labour Conference (87th Session), Geneva, Switzerland, 1–17 June 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen, J.; Muchiri, F.; Lehtinen, S. Decent work, ILO’s response to the globalization of working life: Basic concepts and global implementation with special reference to occupational health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- ILO. World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2022; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra, M.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Rossier, J. Introduction to the special section: Life design interventions (counseling, guidance, education) for decent work and sustainable development. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2022, 22, 577–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.A.; Domene, J.F.; Botia, L.A.; Chiang, M.M.J.; Gendron, M.R.; Pradhan, K. Revitalising decent work through inclusion: Toward relational understanding and action. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2021, 49, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guichard, J. From career guidance to designing lives acting for fair and sustainable development. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2022, 22, 581–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D.L.; Olle, C.; Connors-Kellgren, A.; Diamonti, A.J. Decent Work: A Psychological Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drabik-Podgórna, V.; Podgórny, M. Decent work in Poland: A preliminary study. Suggestions for educational and counselling practice. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2022, 22, 759–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haiming, H.U.; Yan, Y. An Integrative Literature Review and Future Directions of Decent Work. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2020, 20, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasna, A.; Sehnbruch, K.; Burchell, B. Decent work: Conceptualization and policy Impact. In Decent Work and Economic Growth. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A., Brandli, L., Lange, S.A., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. Decent Work Agenda; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. Non-Sandard Employment around the World: Understanding Challenges, Shaping Prospects; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. United Nation of Human Rights. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, Implementing the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M.L. Constructing careers: Actor, agent, and author. J. Employ. Couns. 2011, 48, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guichard, J. Life-long self-construction. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2005, 5, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L.; Nota, L.; Rossier, J.; Dauwalder, J.P.; Duarte, M.E.; Guichard, J.; Soresi, S.; Van Esbroeck, R.; Van Vianen, A.E. Life designing: A paradigm for career construction in the 21st century. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 75, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.E.; Paixão, M.P.; da Silva, J.T. Life-Design Counselling from an Innovative Career Counselling Perspective. In Handbook of Innovative Career Counselling; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guichard, J. Self-constructing. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 75, 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanaviciute, I.; Bühlmann, F.; Rossier, J. Sustainable careers, vulnerability, and well-being: Towards an integrative approach. In Handbook of Innovative Career Counselling; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Nota, L.; Soresi, S.; Di Maggio, I.; Santilli, S.; Ginevra, M.C. Sustainable Development, Career Counselling and Career Education; Springer: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Q.; Shuang, L.; Ting, W. The relationship between decent work and engagement: Role of intrinsic motivation and psychological needs. J. Sichuan Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2016, 5, 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, T.; Pais, L.; Rebelo Dos Santos, N.; Moreira, J.M. The Decent Work Questionnaire: Development and validation in two samples of knowledge workers. Int. Lab. Rev. 2018, 157, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Allan, B.A.; England, J.W.; Blustein, D.L.; Autin, K.L.; Douglass, R.P.; Ferreira, J.; Santos, E.J.R. The development and initial validation of the Decent Work Scale. J. Couns. Psychol. 2017, 64, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- England, J.W.; Duffy, R.D.; Gensmer, N.P.; Kim, H.J.; Buyukgoze-Kavas, A.; Larson-Konar, D.M. Women attaining decent work: The important role of workplace climate in Psychology of Working Theory. J. Couns. Psychol. 2020, 67, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tebbe, E.A.; Allan, B.A.; Bell, H.L. Work and well-being in TGNC adults: The moderating effect of workplace protections. J. Couns. Psychol. 2019, 66, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglass, R.P.; Velez, B.L.; Conlin, S.E.; Duffy, R.D.; England, J.W. Examining the psychology of working theory: Decent work among sexual minorities. J. Couns. Psychol. 2017, 64, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Gensmer, N.; Allan, B.A.; Kim, H.J.; Douglass, R.P.; England, J.W.; Autin, K.L.; Blustein, D.L. Developing, validating, and testing improved measures within the Psychology of Working Theory. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 112, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guichard, J. What career and life design interventions may contribute to global, humane, equitable and sustainable development? Studia Poradoz. J. Couns. 2018, 7, 306–331. [Google Scholar]

- Pouyaud, J. For a psychosocial approach to decent work. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duffy, R.D.; Blustein, D.L.; Diemer, M.A.; Autin, K.L. The psychology of working theory. J. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 63, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blustein, D.L.; Masdonati, J.; Rossier, J. Psychology and the International Labor Organization: The Role of Psychology in the Decent Work Agenda; International Labor Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, R.D.; Kim, H.J.; Perez, G.; Prieto, C.; Torgal, C.; Kenny, M. Decent education as a precursor to decent work: An overview and construct conceptualization. J. Vocat. Behav. 2022, 138, 103771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmigrod, L.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Robbins, T.W. Cognitive underpinnings of nationalistic ideology in the context of Brexit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E4532–E4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santilli, S.; Ginevra, M.C.; Nota, L. The relationship between career adaptability and the view of the economy. In Proceedings of the XIII National Conference of the Italian Society of Vocational Guidance (SIO), Roma, Italy, 20–21 January 2023. [Google Scholar]

- García-Feijoo, M.; Eizaguirre, A.; Rica-Aspiunza, A. Systematic review of sustainable-development-goal deployment in business schools. Sustainability 2020, 12, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hooley, T.; Sultana, R.G.; Thomsen, R. The neoliberal challenge to career guidance: Mobilising research, policy and practice around social justice. In Career Guidance for Social Justice; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bettache, K.; Chiu, C.Y.; Beattie, P. The merciless mind in a dog-eat-dog society: Neoliberalism and the indifference to social inequality. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2020, 34, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D.L.; Duffy, R.D. Psychology of working theory. In Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 201–235. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M.L. The theory and practice of career construction. In Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 42–70. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M.L.; Porfeli, E.J. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilhjálmsdóttir, G. Young workers without formal qualifications: Experience of work and connections to career adaptability and decent work. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2021, 49, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammitti, A.; Magnano, P.; Santisi, G. The concepts of work and decent work in relationship with self-efficacy and career adaptability: Research with quantitative and qualitative methods in adolescence. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 660721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keszei, A.P.; Novak, M.; Streiner, D.L. Introduction to health measurement scales. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 68, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.A.; Watson, D.B. Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Vijver, F.; Tanzer, N.K. Bias and equivalence in cross-cultural assessment: An overview. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 54, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Polit, D.; Beck, C. Essentials of Nursing Research: Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadephia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.; Fidell, L. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed.; Pearson: Essex, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Child, D. The Essentials of Factor Analysis, 3rd ed.; Continuum International Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Eval. 2005, 10, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, J.L. A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika 1965, 30, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velicer, W.F.; Eaton, C.A.; Fava, J.L. Construct explication through factor or component analysis: A review and evaluation of alternative procedures for determining the number of factors or components. In Problems and Solutions in Human Assessment: Honoring Douglas N. Jackson at Seventy; Goffin, R.D., Helmes, E., Eds.; Kluwer Academic: Norwell, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 41–71. [Google Scholar]

- Cattell, R.B. The scree test for the number of factors. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1966, 1, 245–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttman, L. Some necessary conditions for common-factor analysis. Psychometrika 1954, 19, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’connor, B.P. SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer’s MAP test. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2000, 32, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Bearden, W.O.; Sharma, S. Scaling Procedures: Issues and Applications; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington, R.L.; Whittaker, T.A. Scale development research: A content analysis and recommendations for best practices. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 34, 806–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 8.80. Lincolnwood; Scientific Software International Inc.: Skokie, IL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra, A.; Bentler, P.M. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika 2001, 66, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bentler, P.M. EQS Structural Equations Program Manual, 6th ed.; Multivariate Software, Inc.: Encino, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Steiger, J.H. Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1990, 25, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Test. Struct. Equ. Model. 1993, 154, 136–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language; Scientific Software International: Skokie, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M.F.; Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R.D. Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory (WAMI). J. Career Assess. 2012, 20, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pavot, W.; Diener, E. Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychol. Assess. 1993, 5, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, B.A.; Tebbe, E.A.; Bouchard, L.M.; Duffy, R.D. Access to decent and meaningful work in a sexual minority population. J. Career Assess. 2019, 27, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlveen, P.; Hoare, P.N.; Perera, H.N.; Kossen, C.; Mason, L.; Munday, S.; Alchin, C.; Creed, A.; McDonald, N. Decent work’s association with job satisfaction, work engagement, and withdrawal intentions in Australian working adults. J. Career Assess. 2021, 29, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnano, P.; Zarbo, R.; Santisi, G. Evaluating meaningful work: Psychometric properties of the work and meaning inventory (WAMI) in Italian context. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 12756–12767. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.D. Mean and covariance structures (MACS) analyses of cross-cultural data: Practicaland theoretical issues. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1997, 32, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusticus, S.A.; Hubley, A.M.; Zumbo, B.D. Measurement invariance of the Appearance Schemas Inventory–Revised and the Body Image Quality of Life Inventory across age and gender. Assessment 2008, 15, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, B.M.; Stewart, S.M. Teacher’s corner: The MACS approach to testing for multigroup invariance of a second-order structure: A walk through the process. Struct. Equ. Model. 2006, 13, 287–321. [Google Scholar]

- Okpara, J.O. Gender and the relationship between perceived fairness in pay, promotion, and job satisfaction in a sub-Saharan African economy. Women Manag. Rev. 2006, 21, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, C.; Monk-Turner, E.; Sumter, M. Promotional opportunities: How women in corrections perceive their chances for advancement at work. Gend. Issues 2010, 27, 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wynn, A.T. Gender, parenthood, and perceived chances of promotion. Sociol. Persp. 2017, 60, 645–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, H. Career adaptability as a strategy to improve sustainable employment: A proactive personality perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12889. [Google Scholar]

- Soresi, S.; Nota, L.; Ferrari, L. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale-Italian Form: Psychometric properties and relationships to breadth of interests, quality of life, and perceived barriers. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 705–711. [Google Scholar]

- Nota, L.; Soresi, S.; Ginevra, M.C.; Santilli, S.; Di Maggio, I. The tools of the “Stay passionate, courageous, inclusive, sustainable…” project for guidance to benefit the pursuit of the 2030 Agenda goals. In Proceedings of the XIX National Conference of the Italian Society of Vocational Guidance (SIO), Enna, Italy, 17–19 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Little, T.D. Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, L.M. Analysis of longitudinal data: The integration of theoretical model, temporal design, and statistical model. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2006, 57, 505–528. [Google Scholar]

- Selig, J.P.; Preacher, K.J. Mediation models for longitudinal data in developmental research. Res. Hum. Dev. 2009, 6, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables. Mplus User’s Guide; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Little, T.D.; Cunningham, W.A.; Shahar, G.; Widaman, K.F. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, S.M.; Maxwell, S.E. Implications of recent developments in structural equation modeling for counseling psychology. Couns. Psychol. 1999, 27, 485–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, B.A.; Autin, K.L.; Duffy, R.D.; Sterling, H.M. Decent and meaningful work: A longitudinal study. J. Couns. Psychol. 2020, 67, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D.L.; Lysova, E.I.; Duffy, R.D. Understanding decent work and meaningful work. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2023, 10, 289–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammitti, A.; Moreno-Morilla, C.; Romero-Rodríguez, S.; Magnano, P.; Marcionetti, J. Relationships between self-efficacy, job instability, decent work, and life satisfaction in a sample of Italian, Swiss, and Spanish students. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masdonati, J.; Schreiber, M.; Marcionetti, J.; Rossier, J. Decent work in Switzerland: Context, conceptualization, and assessment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 12–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J.A.; Haase, R.F.; Santos, E.R.; Rabaça, J.A.; Figueiredo, L.; Hemami, H.G.; Almeida, L.M. Decent work in Portugal: Context, conceptualization, and assessment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 112, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimrose, J.; McMahon, M.; Watson, M. Women’s Career Development throughout the Lifespan: An International Exploration; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fassinger, R.E. Workplace diversity and public policy: Challenges and opportunities for psychology. Am. Psychol. 2008, 63, 252–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Kim, H.J.; Allan, B.A.; Prieto, C.G. Predictors of decent work across time: Testing propositions from Psychology of Working Theory. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 123, 103507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson-Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

| Item | M | DS | Range | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 4.23 | 0.97 | 1–5 | −1.41 | 1.76 |

| Item 2 | 4.30 | 0.98 | 1–5 | −1.51 | 1.84 |

| Item 3 | 4.06 | 0.91 | 1–5 | −0.81 | 0.39 |

| Item 4 | 3.72 | 1.15 | 1–5 | −0.57 | −0.54 |

| Item 5 | 4.14 | 0.97 | 1–5 | −1.04 | 0.59 |

| Item 6 | 4.05 | 0.97 | 1–5 | −0.91 | 0.60 |

| Item 7 | 4.68 | 0.61 | 1–5 | −2.16 | 5.55 |

| Variable | Real Data Eigenvalues | Mean of Random Eigenvalues | 95th Percentile of Random Eigenvalues |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.526 | 1.148 | 1.212413 |

| 2 | 0.878 | 1.076 | 1.112576 |

| 3 | 0.770 | 1.024 | 1.054759 |

| 4 | 0.704 | 0.973 | 0.999049 |

| 5 | 0.610 | 0.922 | 0.957782 |

| 6 | 0.512 | 0.859 | 0.901972 |

| Item | Factor Loading |

|---|---|

| Item 1 | 0.60 |

| Item 2 | 0.51 |

| Item 3 | 0.47 |

| Item 4 | 0.46 |

| Item 5 | 0.69 |

| Item 6 | 0.58 |

| Meaningful Work | Life Satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|

| Decent work | 0.21 ** | 0.15 ** |

| χ2 | df | p | ∆χ2 | ∆df | P | RMSEA | RMSEA 90% CI | CFI | NNFI | SRMR | Latent Mean: Man | Latent Mean: Woman | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural invariance | 23.46 | 18 | 0.17 | - | - | - | 0.035 | 0.000–0.069 | 0.990 | 0.983 | 0.036 | - | - |

| Weak invariance | 25.77 | 23 | 0.31 | - | - | - | 0.022 | 0.000–0.057 | 0.995 | 0.993 | 0.035 | - | - |

| Strong invariance | 34.21 | 28 | 0.19 | - | - | - | 0.028 | 0.000–0.059 | 0.988 | 0.988 | 0.038 | - | - |

| Homogeneity of variance | 36.26 | 29 | 0.16 | 2.04 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.030 | 0.000–0.059 | 0.987 | 0.986 | 0.050 | - | - |

| Latent mean invariance | 68.67 | 29 | <0.001 | 34.46 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.071 | 0.049–0.093 | 0.926 | 0.924 | 0.035 | 3.85 | 4.18 |

| Men | Women | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ω | 2 | 3 | M | SD | M | SD | |

| 1. Social Economy | 0.77 | 0.168 * | 0.324 ** | 22.13 | 3.73 | 23.83 | 3.50 |

| 2. Curiosity | 0.92 | 0.17 * | 23.48 | 3.35 | 23.65 | 3.48 | |

| 3. Decent Work | 0.83 | 22.48 | 3.79 | 23.60 | 4.52 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zammitti, A.; Valbusa, I.; Santilli, S.; Ginevra, M.C.; Soresi, S.; Nota, L. Development and Validation of the Decent Work for Inclusive and Sustainable Future Construction Scale in Italy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11749. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511749

Zammitti A, Valbusa I, Santilli S, Ginevra MC, Soresi S, Nota L. Development and Validation of the Decent Work for Inclusive and Sustainable Future Construction Scale in Italy. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11749. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511749

Chicago/Turabian StyleZammitti, Andrea, Isabella Valbusa, Sara Santilli, Maria Cristina Ginevra, Salvatore Soresi, and Laura Nota. 2023. "Development and Validation of the Decent Work for Inclusive and Sustainable Future Construction Scale in Italy" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11749. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511749

APA StyleZammitti, A., Valbusa, I., Santilli, S., Ginevra, M. C., Soresi, S., & Nota, L. (2023). Development and Validation of the Decent Work for Inclusive and Sustainable Future Construction Scale in Italy. Sustainability, 15(15), 11749. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511749