Work-Life Balance and Employee Satisfaction during COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Work-Life Balance

2.2. The Relationship between WLB and Job Satisfaction

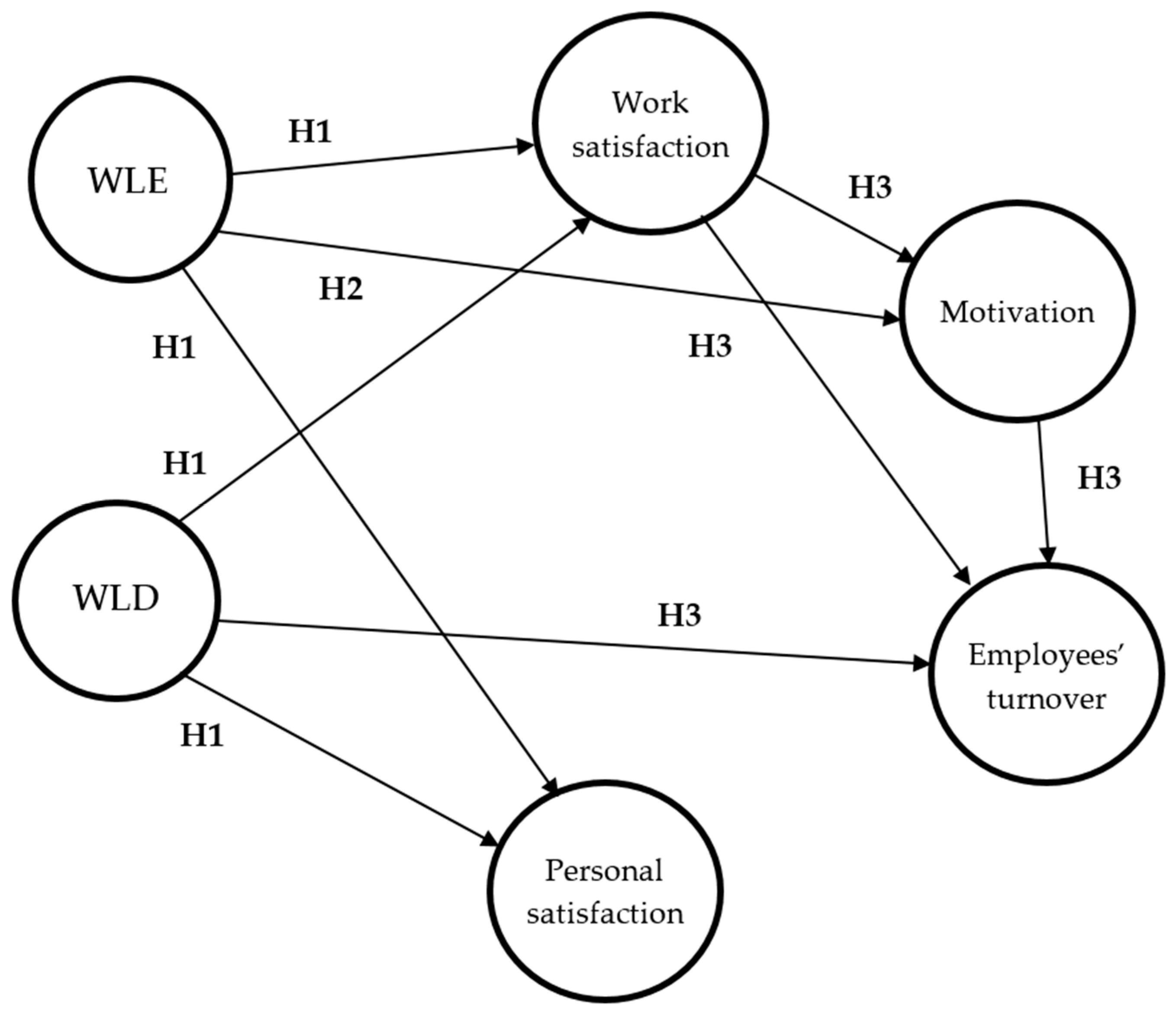

3. Research Methodology

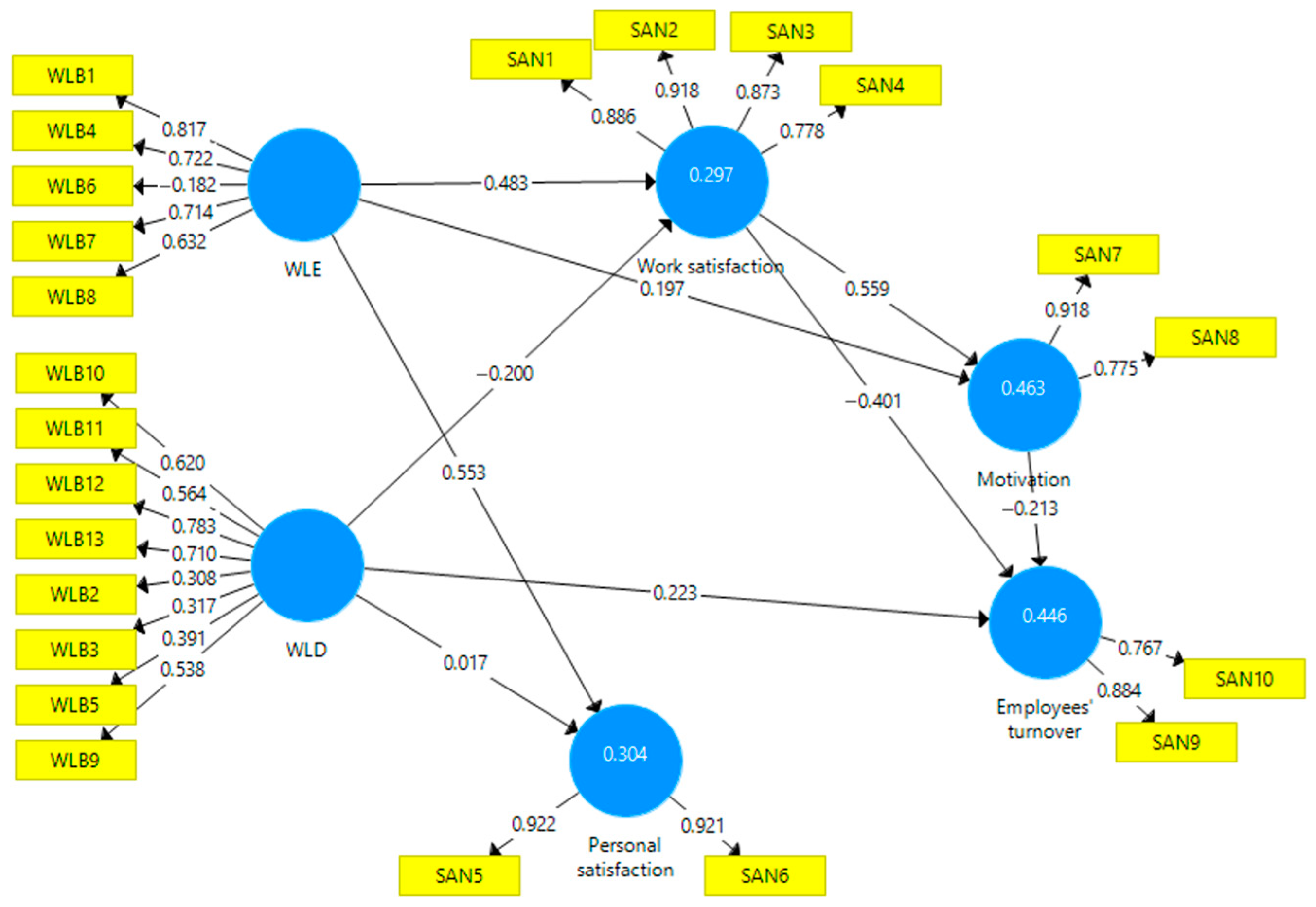

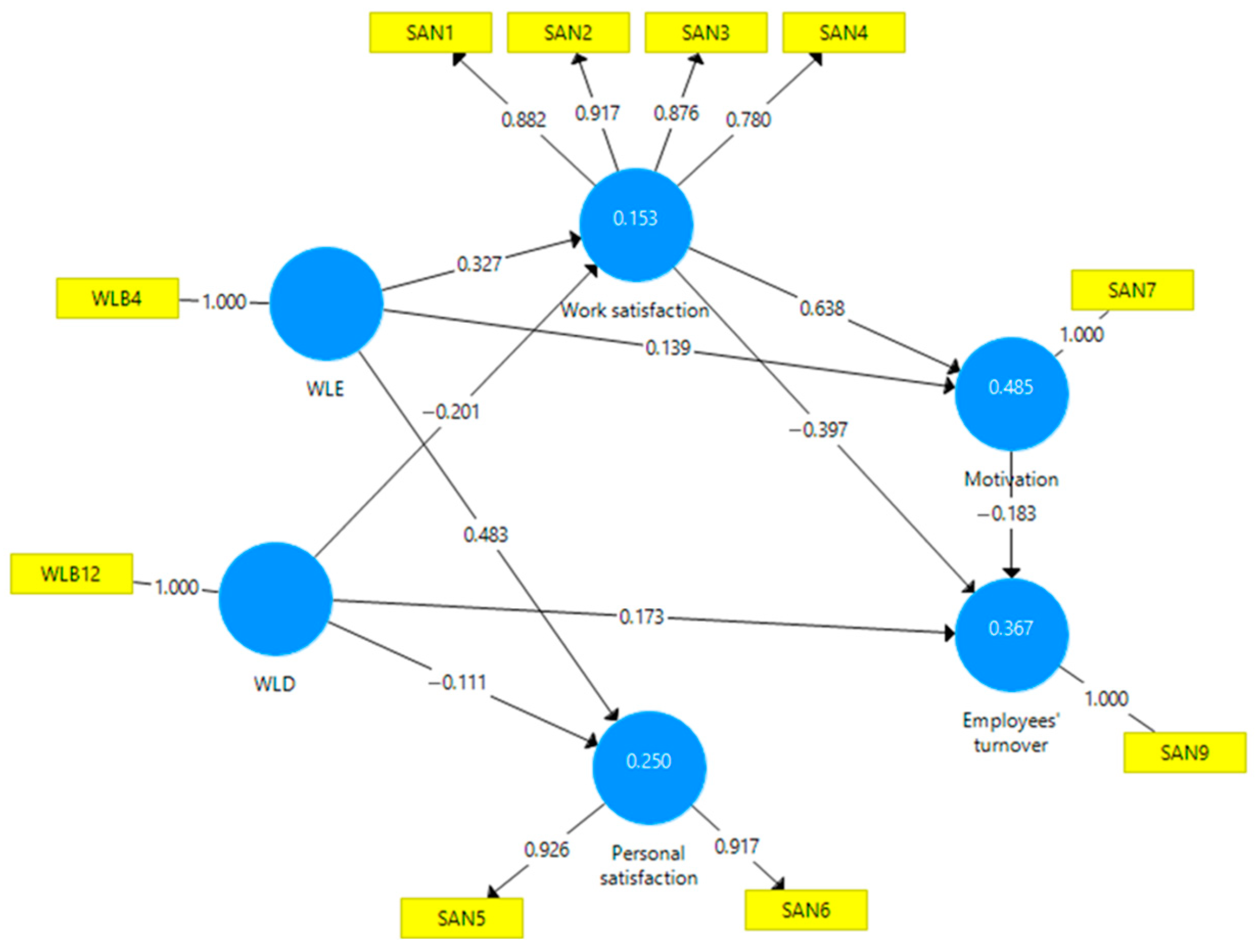

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clark, S.C. Work/Family Border Theory: A New Theory of Work/Family Balance. Hum. Relat. 2000, 53, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, H.J.; Collins, K.M.; Shaw, J.D. The Relation between Work-Family Balance and Quality of Life. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 510–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowska, U.; Tyranska, M.; Wisniewska, S. The Workplace and Work-Life Balance during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Sklodowska Sect. H-Oeconomia 2021, 55, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, P.; Gomes, S. Work-Life Balance and Work from Home Experience: Perceived Organizational Support and Resilience of European Workers during COVID-19. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Jung, S.-H.; Seok, B.-I.; Choi, H.-J. The Relationship among Four Lifestyles of Workers amid the COVID-19 Pandemic (Work-Life Balance, YOLO, Minimal Life, and Staycation) and Organizational Effectiveness: With a Focus on Four Countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erro-Garcés, A.; Urien, B.; Čyras, G.; Janušauskienė, V.M. Telework in Baltic Countries during the Pandemic: Effects on Wellbeing, Job Satisfaction, and Work-Life Balance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorber, M.; Dobnik, M. The Importance of Monitoring the Work-Life Quality during the COVID-19 Restrictions for Sustainable Management in Nursing. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordenmark, M.; Landstad, B.J.; Tjulin, Å.; Vinberg, S. Life Satisfaction among Self-Employed People in Different Welfare Regimes during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Significance of Household Finances and Concerns about Work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, B. The Agency Gap in Work-Life Balance: Applying Sen’s Capabilities Framework within European Contexts. Soc. Politics 2011, 18, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. A Treatise on the Family, Enlarged ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hogarth, T.; Bosworth, D. Future Horizons for Work—Life Balance. Beyond Current Horizons: Technology, Children, Schools, and Families. Available online: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/ier/publications/2009/ch4_hogarthterence_futurehorizonsforworklifebalance20090116.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Duncan, K.A.; Pettigrew, R.N. The effect of work arrangements on perceptions of work-family balance. Community Work Fam. 2012, 15, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voydanoff, P. Toward a conceptualization of perceived work-family fit and balance: A demands and resources approach. J. Marriage Fam. 2005, 67, 822–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wang, X.; Li, A.; Zhou, L. Predicting work–family balance: A new perspective on person–environment fit. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Carlson, D.S. Conceptualizing work-family balance: Implications for practice and research. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2007, 9, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frone, M.R. Work-family balance. In Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology; Quick, J.C., Tetrick, L.E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Wayne, J.H.; Butts, M.M.; Casper, W.J.; Allen, T.D. In search of balance: A conceptual and empirical integration of multiple meanings of work-family balance. Pers. Psychol. 2017, 70, 167–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JyothiSree, V.; Jyothi, P.N. Assessing Work-Life Balance: From Emotional Intelligence and Role Efficacy of Career Women. Adv. Manag. 2012, 5, 332. [Google Scholar]

- Folbre, N. Who Pays for the Kids: Gender and the Structure of Constraint; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan, C. Gender and Working Time in Industrialized Countries. In Working Time and Workers’ Preferences in Industrialized Countries, 1st ed.; Messenger, J.C., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 108–146. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; McCann, D. Working Time Capability: Towards Realizing Individual Choice. In Decent Working Time: New Trends, New Issues; Boulin, J.Y., Lallement, M., Messenger, J.C., Eds.; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; pp. 65–91. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_071859.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- Tziner, A.; Shkoler, O. Leadership styles, and work attitudes: Does age moderate their relationship? J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2018, 34, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pinder, C.C. Work Motivation in Organizational Behavior, 2nd ed.; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kanfer, R.; Frese, M.; Johnson, R.E. Work-related motivation: A century of progress. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 338–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, G.P.; Pinder, C.C. Work motivation theory and research at the dawn of the twenty-first century. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2005, 56, 485–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, W. Confessions of a Workaholic: The Facts about Work Addiction; World Publishing Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Harpaz, I.; Snir, R. Workaholism: Its definition and nature. Hum. Relat. 2003, 56, 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, B.J. Behavioral Perspectives on Personality and Self. Psychol. Rec. 2015, 65, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, N.; McCorduck, P. Where Are the Women in Information Technology? Available online: https://alejandrobarros.com/wp-content/uploads/old/Where_are_the_Women_in_Information_Technology.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Burke, R.J.; Fiksenbaum, L. Work Motivations, Work Outcomes, and Health: Passion versus Addiction. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, J.A.; Waters, L.E. Workaholic worker type differences in work-family conflict: The moderating role of supervisor support and flexible work scheduling. Career Dev. Int. 2006, 11, 418–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burke, R.J. Workaholism in organizations: Gender differences. Sex Roles 1999, 41, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, B.; Fahlén, S. Competing Scenarios for European Fathers: Applying Sen’s Capabilities and Agency Framework to Work-Family Balance. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2009, 624, 214–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrili, G.; Avram, A.; Nicolescu, A.C. Gender Equality and Firm Financial Performance. The Case of Central and Eastern Europe Financial and IT Sectors. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328886127_GENDER_EQUALITY_AND_FIRM_FINANCIAL_PERFORMANCE_THE_CASE_OF_CENTRAL_AND_EASTERN_EUROPE_FINANCIAL_AND_IT_SECTORS (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Aycan, Z.; Kanungo, R.N. Cross-cultural industrial and organizational psychology: A critical appraisal of the field and future directions. In Handbook of Industrial, Work and Organizational Psychology; Anderson, N., Ones, D.S., Sinangil, H.K., Viswesvaran, C., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2002; Volume 3, pp. 385–408. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, D.E. Perspectives on the Study of Work-life Balance. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2002, 41, 255–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudrack, P.E. Moral Reasoning, and Personality Traits. Psychol. Rep. 2006, 98, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, B.E.; Flowers, C.; Carroll, J. Work Stress and Marriage: A Theoretical Model Examining the Relationship between Workaholism and Marital Cohesion. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2001, 8, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Oerlemans, W.; Sonnentag, S. Workaholism and daily recovery: A day reconstruction study of leisure activities. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Hetland, J.; Molde, H.; Pallesen, S. “Workaholism” and potential outcomes in well-being and health in a cross-occupational sample. Stress Health 2011, 27, e209–e214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; Van Rhenen, W. Workaholism, burnout, and work engagement: Three of a kind or three different kinds of employee well-being? Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 173–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.; Dasgupta, S.; Huynh, T.D.; Xia, Y. Were Stay-at-Home Orders during COVID-19 Harmful for Business? The Market’s View. 2020. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm/SSRN_ID3660246_code1886367.pdf?abstractid=3660246&mirid=1 (accessed on 3 April 2022).

- Ellder, E. Telework, and daily travel: New evidence from Sweden. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 86, 102777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stănciulescu, E. Telemunca și munca la domiciliu în contextul actual [Teleworking și working from Home in the Current Environment]. CECCAR Bus. Rev. 2020, 10, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.J.; Hensher, D.A.; Wei, E. Slowly coming out of COVID-19 restrictions in Australia: Implications for working from home and commuting trips by car and public transport. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 88, 102846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawashima, T.; Nomura, S.; Tanoue, Y.; Yoneoka, D.; Eguchi, A.; Ng, C.F.S.; Matsuura, K.; Shi, S.; Makiyama, K.; Uryu, S.; et al. Excess All-Cause Deaths during Coronavirus Disease Pandemic, Japan, January–May 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, M.H. Factors influencing home-based telework in Hanoi (Vietnam) during and after the COVID-19 era. Transportation 2021, 48, 3207–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shereen, M.A.; Khan, S.; Kazmi, A.; Bashir, N.; Siddique, R. COVID-19 infection: Emergence, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J. Adv. Res. 2020, 24, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingel, J.I.; Neiman, B. How many jobs can be done at home? J. Public Econ. 2020, 189, 104235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, T. Telework in the spread of COVID-19. Inf. Econ. Policy 2022, 60, 100987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeri, T.; Caiumi, A.; Paccagnella, M. Mitigating the Work-Safety Trade-Off. Available online: https://wol.iza.org/opinions/mitigating-the-work-safety-trade-off (accessed on 16 April 2022).

- Chung, H.; van der Lippe, T. Flexible Working, Work-Life Balance, and Gender Equality: Introduction. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 151, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lopez-Igual, P.; Rodríguez-Modroño, P. Who Is Teleworking and Where from? Exploring the Main Determinants of Telework in Europe. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, A.; Kramer, K.Z. The Potential Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Occupational Status, Work from Home, and Occupational Mobility. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 119, 103442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irawanto, D.W.; Novianti, K.R.; Roz, K. Work from Home: Measuring Satisfaction between Work-Life Balance and Work Stress during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia. Economies 2021, 9, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, C.K.; Reimann, M.; Diewald, M. Do Work-Life Measures Really Matter? The Impact of Flexible Working Hours and Home-Based Teleworking in Preventing Voluntary Employee Exits. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, A.M.; Mangel, R. The Impact of Work-Life Programs on Firm Productivity. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1225–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.T.B.; Fransman, E.I. Flexi Work, Financial Well-Being, Work-Life Balance and Their Effects on Subjective Experiences of Productivity and Job Satisfaction of Females in an Institution of Higher Learning. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2018, 21, a1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lund, D.B. Organizational Culture and Job Satisfaction. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2003, 18, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D. Job attitudes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 341–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Weiss, H.W.; Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D.; Hulin, C.L. Job attitudes, job satisfaction, and job affect: A century of continuity and change. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 356–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. Job satisfaction and job performance: A theoretical analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1970, 5, 484–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.E. Job Satisfaction in Britain. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 1996, 34, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Gao, J. Does Telework Stress Employees Out? A Study on Working at Home and Subjective Well-Being for Wage/Salary Workers. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 21, 2649–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belzunegui-Eraso, A.; Erro-Garces, A. Teleworking in the Context of the COVID-19 Crisis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, G.G.; Bulger, C.A.; Smith, C.S. Beyond work and family: A measure of work/nonwork interference and enhancement. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayman, J. Psychometric assessment of an instrument designed to measure work-life balance. Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 13, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Tetrick, L.E.; Buffardi, L.C. Measurement issues in research on the work-home interface. In Work-Life Balance: A Psychological Perspective; Jones, F., Burke, R.J., Westman, M., Eds.; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2006; pp. 90–114. [Google Scholar]

- Brayfield, A.H.; Rothe, H.F. An index of job satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 1951, 35, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinval, J.; Maroco, J. Short index of job satisfaction: Validity evidence from Portugal and Brazil. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kaplan, D. Structural Equation Modeling. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Neil, J., Smelser, P., Baltes, B., Eds.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 15215–15222. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.A. Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The Measurement of Engagement and Burnout: A Two Sample Confirmatory Factor Analytic Approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beek, I.; Hu, Q.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; Schreurs, B.H.J. For Fun, Love, or Money: What Drives Workaholic, Engaged, and Burned-Out Employees at Work? Appl. Psychol. 2011, 61, 30–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nijhuis, N.; van Beek, I.; Taris, T.; Schaufeli, W. De motivatie en prestatie van werkverslaafde, bevlogen en opgebrande werknemers [The motivation and performance of workaholic, engaged, and burned-out workers]. Gedrag Organ. 2012, 25, 325–346. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.; Albrecht, S.; Leiter, M. Key questions regarding work engagement. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2011, 20, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Bal, P.M. Weekly Work Engagement and Performance: A Study among Starting Teachers. J. Occup. Psychol. 2010, 83, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cowling, M.; Brown, R.; Rocha, A. Did you save some cash for a rainy COVID-19 day? The crisis and SMEs. Int. Small Bus. J. 2020, 38, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitka, M.; Štarchoň, P.; Caha, Z.; Lorincová, S.; Sedliačiková, M. The global health pandemic and its impact on the motivation of employees in micro and small enterprises: A case study in the Slovak Republic. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraz. 2022, 35, 458–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, A.; Cattan, S.; Dias, M.S.; Farquharson, C.; Kraftman, L.; Krutikova, S.; Phimister, A.; Sevilla, A. How Are Mothers and Fathers Balancing Work and Family under Lockdown? IFS Briefing Note; BN290; Institute for Fiscal Studies: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://ifs.org.uk/uploads/BN290-Mothers-and-fathers-balancing-work-and-life-under-lockdown.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Sevilla, A.; Smith, S. Baby Steps: The Gender Division of Childcare during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2020, 36, S169–S186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Boca, D.; Oggero, N.; Profeta, P.; Rossi, M.C. Women’s Work, Housework, and Childcare, before and during COVID-19. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2020, 18, 1001–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codagnone, C.; Bogliacino, F.; Gómez, C.; Charris, R.; Montealegre, F.; Liva, G.; Lupiáñez-Villanueva, F.; Folkvord, F.; Veltri, G.A. Assessing concerns for the economic consequence of the COVID-19 response and mental health problems associated with economic vulnerability and negative economic shock in Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.J.; Hensher, D.A. Insights into the impact of COVID-19 on household travel and activities in Australia—The early days of easing restrictions. Transp. Policy 2020, 99, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound and the International Labour Office. Working Anytime, Anywhere: The Effects on the World of Work; Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg and the International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2017/workinganytime-anywhere-the-effects-on-the-world-of-work (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Takami, T. Working from Home and Work-Life Balance during COVID-19: The Latest Changes and Challenges in Japan. Available online: https://www.jil.go.jp/english/jli/documents/2021/033-03.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Abele, A.E.; Volmer, J. Dual-Career Couples: Specific Challenges for Work-Life Integration. In Creating Balance? International Perspectives on the Work-Life Integration of Professionals; Kaiser, S., Ringlstetter, M.J., Eikhof, D.R., Pina e Cunha, M., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Wepfer, A.G.; Allen, T.D.; Brauchli, R.; Jenny, G.J.; Bauer, G.F. Work-Life Boundaries and Well-Being: Does Work-to-Life Integration Impair Well-Being Through Lack of Recovery? J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 33, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, S. Work-Life-Integration through Flexible Work Arrangements: A Holistic Approach to Work-Life Balance. J. Maharaja Agrasen Coll. High. Educ. 2017, 4, 1–8. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm/SSRN_ID3379084_code2541941.pdf?abstractid=3379084&mirid=1 (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Netermeyer, R.G.; Boles, J.; Mcmurrian, R.C. Development and validation of work-family and family-work conflict scales. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.; Powell, G.N. When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstad, F.T.; Meier, T.; Laurenz, L.M.; Fasel, U.; Elfering, A.; Semmer, N. A meta-analysis of work-family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Answer Options | Frequencies (Percentage) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 41.0 |

| Female | 59.0 | |

| Age | 20–30 years | 10.1 |

| 31–45 years old | 43.3 | |

| 46–55 years old | 34.7 | |

| Over 55 years | 11.9 | |

| Education level | High school | 18.3 |

| Bachelor | 35.1 | |

| Master | 39.6 | |

| PhD | 7.1 | |

| Position | Managerial | 16.4 |

| Execution | 83.6 |

| Latent Variable | Code | Observable Variable | Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work-life equilibrium | WLB1 | I am satisfied with the way I perform my tasks at work. | Never, rarely, neutral, often, always |

| WLB4 | I have time each week for personal/family activities. | ||

| WLB6 | When I finish my work schedule, I stop thinking about tasks. | ||

| WLB7 | I prioritize my work tasks at work. | ||

| WLB8 | I prioritize the events I have to attend in private. | ||

| Work-life disequilibrium | WLB2 | During the pandemic, I exceeded my work schedule. | |

| WLB3 | When I had difficult tasks or pressing deadlines at work, I also worked in my free time. | ||

| WLB5 | My supervisor contacts me in my spare time for work-related matters. | ||

| WLB9 | During the COVID-19 pandemic, I sacrificed my sleep to spend more time with my family. | ||

| WLB10 | During the COVID-19 pandemic, we worked harder than before. | ||

| WLB11 | During the COVID-19 pandemic, I sacrificed my sleep to fulfill my duties at work. | ||

| WLB12 | During this time, I felt increased pressure/stress at work. | ||

| WLB13 | During this period, I requested more days off than before the pandemic. | ||

| Work satisfaction | SAN1 | I am happy to go to work. | Total disagreement, partial disagreement, neutral, partial agreement, total agreement |

| SAN2 | I feel fulfilled at work. | ||

| SAN3 | Work contributes to my overall happiness. | ||

| SAN4 | At work, I feel inspired and creative. | ||

| Personal satisfaction | SAN5 | I am happy with my family. | |

| SAN6 | I am satisfied with my personal life. | ||

| Motivation | SAN7 | How do you assess your level of motivation at work for the period 1 March 2020 so far? | Very demotivated, demotivated, neutral, motivated, very motivated |

| SAN8 | How do you assess your performance at work for 1 March 2020 so far, compared to the previous period? | Dropped a lot, lower, same level, slightly better, excellent | |

| Employees’ turnover intention | SAN9 | You are considering leaving the organization for a career or a better salary. | Constant, often, sometimes, rarely, never |

| SAN10 | Would you recommend the organization you work for to others looking for a job? | No, yes |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employee turnover | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Motivation | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Personal satisfaction | 0.822 | 0.918 | 0.849 |

| WLD | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| WLE | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Work satisfaction | 0.887 | 0.922 | 0.749 |

| Original Sample (O) | t-Statistics | p-Values | F-Squared | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation –> Employee turnover (H3) | −0.183 | 2.585 | 0.010 | 0.044 |

| WLD –> Employee turnover (H3) | 0.173 | 3.767 | 0.000 | 0.080 |

| WLD –> Personal satisfaction (H1) | −0.111 | 2.340 | 0.020 | 0.000 |

| WLD –> Work satisfaction (H1) | −0.201 | 3.549 | 0.000 | 0.056 |

| WLE –> Motivation (H2) | 0.139 | 2.401 | 0.017 | 0.054 |

| WLE –> Personal satisfaction (H1) | 0.483 | 9.076 | 0.000 | 0.432 |

| WLE –> Work satisfaction (H1) | 0.327 | 5.700 | 0.000 | 0.327 |

| Work satisfaction –> Employee turnover (H3) | −0.397 | 5.664 | 0.000 | 0.163 |

| Work satisfaction –> Motivation (H3) | 0.638 | 9.485 | 0.000 | 0.432 |

| Original Sample (O) | t-Statistics | p-Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WLE –> Work satisfaction –> Motivation –> Employee turnover (H3) | −0.038 | 2.308 | 0.021 |

| WLD –> Work satisfaction –> Motivation | −0.128 | 3.002 | 0.003 |

| WLE –> Work satisfaction –> Motivation | 0.209 | 4.679 | 0.000 |

| WLD –> Work satisfaction –> Employee turnover | 0.080 | 3.248 | 0.001 |

| WLE –> Work satisfaction –> Employee turnover (H3) | −0.130 | 3.716 | 0.000 |

| WLE –> Motivation –> Employee turnover (H3) | −0.026 | 1.673 | 0.095 |

| Work satisfaction –> Motivation –> Employee turnover | −0.117 | 2.513 | 0.012 |

| WLD –> Work satisfaction –> Motivation –> Employee turnover | 0.024 | 1.854 | 0.064 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bocean, C.G.; Popescu, L.; Varzaru, A.A.; Avram, C.D.; Iancu, A. Work-Life Balance and Employee Satisfaction during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11631. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511631

Bocean CG, Popescu L, Varzaru AA, Avram CD, Iancu A. Work-Life Balance and Employee Satisfaction during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11631. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511631

Chicago/Turabian StyleBocean, Claudiu George, Luminita Popescu, Anca Antoaneta Varzaru, Costin Daniel Avram, and Anica Iancu. 2023. "Work-Life Balance and Employee Satisfaction during COVID-19 Pandemic" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11631. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511631

APA StyleBocean, C. G., Popescu, L., Varzaru, A. A., Avram, C. D., & Iancu, A. (2023). Work-Life Balance and Employee Satisfaction during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 15(15), 11631. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511631