The Role of Eudaimonic Motivation on the Well-Being of College Athletes: The Chain-Mediating Effect of Meaning Searching and Meaning Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

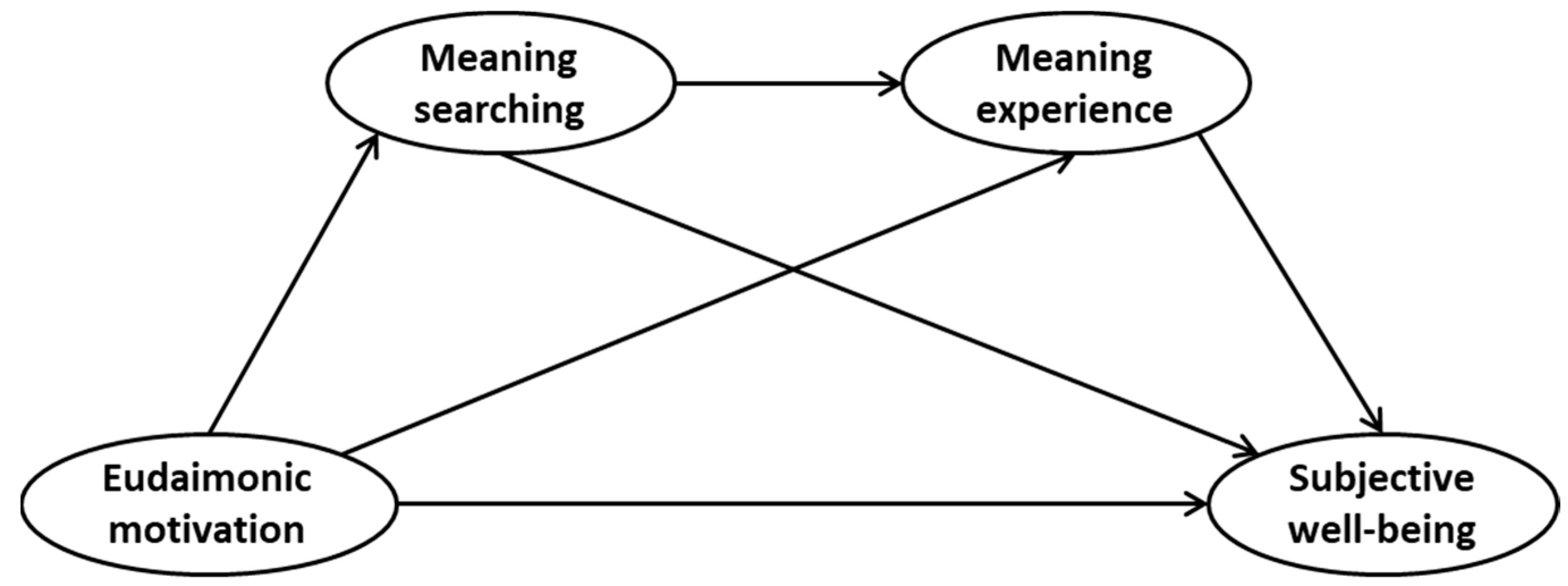

1.1. Eudaimonic Motivation and Subjective Well-Being of College Athletes

1.2. The Role of Meaning Searching in Eudaimonic Motivation and Subjective Well-Being

1.3. The Role of Meaning Experience in Eudaimonic Motivation and Subjective Well-Being

1.4. The Relationship between Meaning Searching and Meaning Experience

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Eudaimonic Motivation

2.2.2. Meaning Searching and Meaning Experience

2.2.3. Positive Emotions and Negative Emotions

2.2.4. Life Satisfaction

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Results of the Common Method Biases Test

3.2. Correlation Analysis Results

3.3. The Chain Mediating Model Analysis Results

4. Discussion

4.1. The Influence of Eudaimonic Motivation on Subjective Well-Being of College Athletes

4.2. The Mediating Effect of Meaning Experience

4.3. The Role of Meaning Searching

4.4. The Chain Mediating Effect of Meaning Searching and Meaning Experience

5. Contributions and Limitations

5.1. Contributions

5.2. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karagiorgakis, A.; Blaker, E.R. The effects of stress on USCAA student-athlete academics and sport enjoyment. Coll. Stud. J. 2021, 55, 429–439. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Oja, B.D.; Kim, H.S.; Chin, J. Developing Student-Athlete School Satisfaction and Psychological Well-Being: The Effects of Academic Psychological Capital and Engagement. J. Sport Manag. 2020, 34, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, A.L.; Milroy, J.J.; Wyrick, D.L.; Hebard, S.P. A social ecological framework: Counselors’ role in improving student athletes’ help-seeking behaviors. J. Coll. Couns. 2021, 24, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, H.; Gayles, J.G.; Bell, L. Student-athletes and mental health experiences. N. Dir. Stud. Serv. 2018, 163, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.T. Mind, Body and Sport: Understanding and Supporting Student-Athlete Mental Wellness. National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2014. Available online: https://www.ncaapublications.com/productdownloads/MindBodySport.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Gustafsson, H.; Carlin, M.; Podlog, L.; Stenling, A.; Lindwall, M. Motivational profiles and burnout in elite athletes: A person-centered approach. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2018, 35, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.M.; King, L. Why positive psychology is necessary. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 216–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Oishi, S. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and life satisfaction. In Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Sanjuán, P.; Ávila, M. The Mediating Role of Coping Strategies on the Relationships between Goal Motives and Affective and Cognitive Components of Subjective Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 1057–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zheng, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Tian, L.; Fang, P. Does goal conflict necessarily undermine wellbeing? A moderated mediating effect of mixed emotion and construal level. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 653512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denny, K.G.; Steiner, H. External and internal factors influencing happiness in elite collegiate athletes. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2009, 40, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingaz, E.O.; Solmaz, S.; Ekiz, M.A.; Guvendi, B. The Relationship between mindfulness and happiness in student-athletes: The role of self-compassion—Mediator or moderator? J. Ration. Emot. Cogn. B 2022, 40, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Brick by brick: The origins, development, and future of self-determination theory. Adv. Motiv. Sci. 2019, 6, 111–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huta, V.; Ryan, R.M. Pursuing pleasure or virtue: The differential and overlapping well-being benefits of hedonic and eudaimonic motives. J. Happiness Stud. 2010, 11, 735–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huta, V.; Waterman, A.S. Eudaimonia and its distinction from hedonia: Developing a classification and terminology for understanding conceptual and operational definitions. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 1425–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortner, C.; Corno, D.; Fung, T.Y.; Rapinda, K. The roles of hedonic and eudaimonic motives in emotion regulation. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2018, 120, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandler, N.; Krauss, A.; Proyer, R.T. Authentic happiness at work: Self- and peer-rated orientations to happiness, work satisfaction, and stress coping. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschor, C.; Proyer, R.T.; Ruch, W. Self- and peer-rated character strengths: How do they relate to satisfaction with life and orientations to happiness? J. Posit. Psychol. 2013, 8, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Frazier, P.; Oishi, S.; Kaler, M. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 53, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; He, M.; Li, J. The relationship between meaning in life and subjective well-being in China: A Meta-analysis. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 24, 1854–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, M.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Peng, K. The search for meaning in life: Growth or crisis. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 26, 2192–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F. Wrestling with our better selves: The search for meaning in life. In The Psychology of Meaning; Markman, K.D., Proulx, T., Lindberg, M.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 215–233. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M.F.; Kawabata, Y.; Shimai, S.; Otake, K. The meaningful life in Japan and the United States: Levels and correlates of meaning in life. J. Res. Personal. 2008, 42, 660–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Liu, L.; Zheng, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Fang, P. Why eudemonia bring more happiness: The multiple mediating roles of meaning of life and emotions. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, V.E. Man’s Search for Meaning; Washington Square Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, M.Y.; Cheung, F.M.; Cheung, S.F. The role of meaning in life and optimism in promoting well-being. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2010, 48, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huta, V. Eudaimonic and hedonic orientations: Theoretical considerations and research findings. In Handbook of Eudaimonic Well-Being; Vitters, J., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Asano, R.; Tsukamoto, S.; Igarashi, T.; Huta, V. Psychometric properties of measures of hedonic and eudaimonic orientations in Japan: The HEMA scale. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braaten, A.; Huta, V.; Tyrany, L.; Thompson, A. Hedonic and eudaimonic motives toward university studies: How they relate to each other and to well-being derived from school. J. Posit. Psychol. Wellbeing 2019, 3, 179–196. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, L.W.; Knight, T.; Richardson, B. An exploration of the well-being benefits of hedonic and eudaimonic behaviour. J. Posit. Psychol. 2013, 8, 322–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, N.; Hunecke, M. The Mindful Hedonist? Relationships between Well-Being Orientations, Mindfulness and Well-Being Experiences. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 3111–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.; Park, N.; Seligman, M.E. Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full life versus the empty life. J. Happiness Stud. 2005, 6, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, S.A.; Masters, K.S.; Park, C.L. A meaningful life is a healthy life: A conceptual model linking meaning and meaning salience to health. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2018, 22, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Oishi, S.; Kashdan, T.B. Meaning in life across the life span: Levels and correlates of meaning in life from emerging adulthood to older adulthood. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.L. Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 13, 257–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Qian, Y.; Ye, J. The relationship between life meaning, life purpose and subjective well-being of medical students. China J. Health Psychol. 2018, 26, 1253–1257. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bradburn, N.M. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1969; pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, L.C.; Ntoumanis, N.; Arthur, C.A. Goal motives and well-being in student-athletes: A person-centered approach. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2020, 42, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Elfenbein, H.A.; Sinha, R.; Bottom, W.P. The effects of emotional expressions in negotiation: A meta-analysis and future directions for research. Hum. Perform. 2020, 33, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. Updated thinking on positivity ratios. Am. Psychol. 2013, 68, 814–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinchenko, A.; Obermeier, C.; Kanske, P.; Schröger, E.; Villringer, A.; Kotz, S.A. The influence of negative emotion on cognitive and emotional control remains intact in aging. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, K.; Cairns, D. Is searching for meaning in life associated with reduced subjective well-being? Confirmation and possible moderators. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 13, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Vohs, K.D.; Aaker, J.L.; Garbinsky, E.N. Some key differences between a happy life and a meaningful life. J. Posit. Psychol. 2013, 8, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L. Understanding happiness: A look into the Chinese folk psychology. J. Happiness Stud. 2001, 2, 407–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Modern economic growth, culture, and subjective wellbeing: Evidence from Arctic Alaska. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 2621–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, F.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X. Chinese adolescents’ coping tactics in a parent-adolescent conflict and their relationships with life satisfaction: The differences between coping with mother and father. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | - | - | 1 | |||||||||

| 2. Grade | - | - | −0.62 | 1 | ||||||||

| 3. Major | - | - | −0.12 ** | −0.06 | 1 | |||||||

| 4. Age | 19.80 | 1.50 | −0.01 | 0.40 *** | −0.01 | 1 | ||||||

| 5. Eudaimonic motivation | 5.10 | 1.20 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 1 | |||||

| 6. Meaning searching | 5.14 | 1.19 | 0.04 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.47 *** | 1 | ||||

| 7. Meaning experience | 4.68 | 1.14 | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.51 *** | 0.40 *** | 1 | |||

| 8. Positive emotions | 2.66 | 0.64 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.47 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.49 *** | 1 | ||

| 9. Negative emotions | 2.13 | 0.59 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.12 ** | 0.04 | −0.22 *** | −0.15 *** | 1 | |

| 10. Life satisfaction | 4.18 | 1.36 | −0.10 * | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.39 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.51 *** | −0.19 *** | 1 |

| Paths | Effect Size | Boot SE | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | |||

| Eudaimonic motivation →Subjective well-being (Direct effect) | 0.359 *** | 0.066 | 0.226 | 0.485 |

| Eudaimonic motivation → Meaning searching → Subjective well-being | −0.040 | 0.038 | −0.117 | 0.032 |

| Eudaimonic motivation → Meaning experience → Subjective well-being | 0.225 *** | 0.045 | 0.148 | 0.326 |

| Eudaimonic motivation → Meaning searching → Meaning experience → Subjective well-being | 0.088 *** | 0.028 | 0.045 | 0.154 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.272 *** | 0.047 | 0.190 | 0.374 |

| Total effect | 0.632 *** | 0.042 | 0.548 | 0.710 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, G.; Sun, W.; Liu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Ding, X.; Liu, Y. The Role of Eudaimonic Motivation on the Well-Being of College Athletes: The Chain-Mediating Effect of Meaning Searching and Meaning Experience. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11598. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511598

Wang G, Sun W, Liu L, Jiang Y, Ding X, Liu Y. The Role of Eudaimonic Motivation on the Well-Being of College Athletes: The Chain-Mediating Effect of Meaning Searching and Meaning Experience. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11598. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511598

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Guangjun, Wujun Sun, Lei Liu, Yuan Jiang, Xiaosheng Ding, and Yuan Liu. 2023. "The Role of Eudaimonic Motivation on the Well-Being of College Athletes: The Chain-Mediating Effect of Meaning Searching and Meaning Experience" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11598. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511598

APA StyleWang, G., Sun, W., Liu, L., Jiang, Y., Ding, X., & Liu, Y. (2023). The Role of Eudaimonic Motivation on the Well-Being of College Athletes: The Chain-Mediating Effect of Meaning Searching and Meaning Experience. Sustainability, 15(15), 11598. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511598