Exploring the Effect of Tour Guide Cultural Interpretation on Tourists’ Loyalty in the Context of the Southern Journey by Emperor Qianlong

Abstract

:1. Introduction

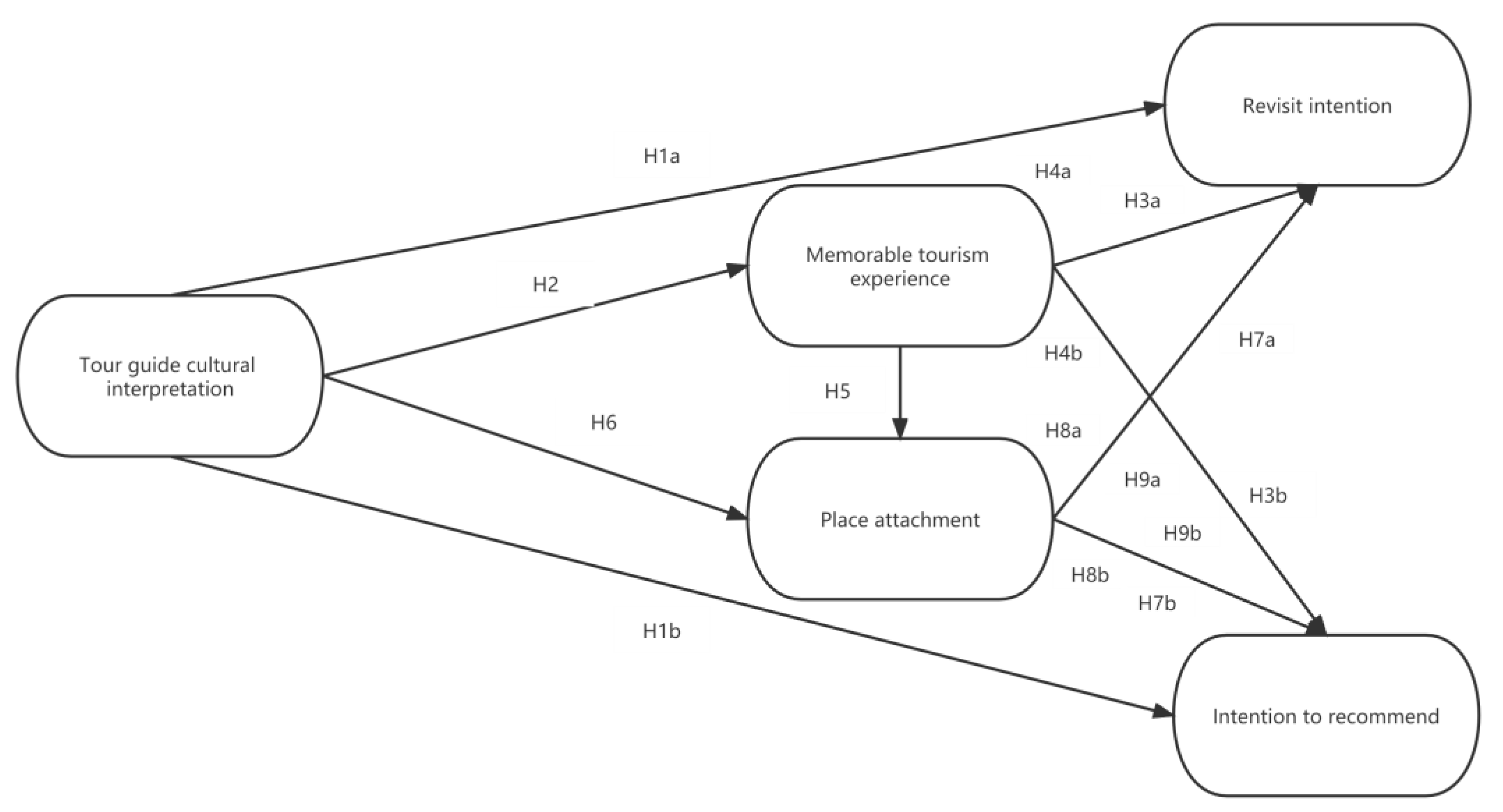

- Does TCI have a positive effect, and a direct or indirect effect, on tourists’ loyalty?

- Do MTE and PA have mediating effects on the relationship between TCI and tourists’ loyalty?

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Tour Guide Interpretation and Tourists’ Loyalty

2.2. Tour Guide Cultural Interpretation and Memorable Tourism Experience

2.3. Memorable Tourism Experience and Tourists’ Loyalty

2.4. The Mediating Role of MTE

2.5. MTE and Place Attachment

2.6. Tour Guide Cultural Interpretation and Place Attachment

2.7. Place Attachment and Tourists’ Loyalty

2.8. The Mediating Role of Place Attachment

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Testing the Hypothesized Structural Model

4.4. Test of Mediating Effect

5. Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xinhuanet, [Story of Yanxi Palace Ratings Lead the National Day]. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1613992885061968298&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 11 October 2018).

- Asian Academy Creative Awards, 2019 FINAL WINNERS LIST. Available online: https://www.asianacademycreativeawards.com/2019-final-winners-list/ (accessed on 7 December 2019).

- Enlightent, [10 Billion Broadcast TV Series]. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzkxNzUxMzI1OA==&mid=2247504219&idx=1&sn=86b916ed559f722c8580a57f6ed0e71b&source=41#wechat_redirect (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- Zhang, H.J. A Flourishing but Starving Age; Chongqing Publishing Group: Chongqing, China, 2016; ISBN 978-7-22-910667-6. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L. Shengjing Palace Painting and Calligraphy; Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2012; ISBN 978-7-53-263718-8. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J. Research on Cultural Activities during Southern Inspection of Emperor Kangxi and Emperor Qianlong-Centered on the Landscape Culture of the Jiangnan Area. Doctoral Dissertation, Soochow University, Suzhou, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Z. An Intellectual History of China; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume two, ISBN 978-90-04-28134-9. Available online: https://brill.com/display/title/25458 (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Kuhn, P.A. Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; ISBN 0-674-82152-1. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Rahman, I. Cultural tourism: An analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.K.; Pinke-Sziva, I.; Berezvai, Z.; Buczkowska-Gołąbek, K. The changing nature of the cultural tourist: Motivations, profiles and experiences of cultural tourists in Budapest. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2021, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogutu, H.; Adol, G.F.C.; Bujdosó, Z.; Andrea, B.; Fekete-Farkas, M.; Dávid, L.D. Theoretical Nexus of Knowledge Management and Tourism Business Enterprise Competitiveness: An Integrated Overview. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Wei, W.; Ding, S.; Xue, J. The relationship between place attachment and tourist loyalty: A meta-analysis. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 43, 100983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, M. Tourism destination loyalty. J. Travel Res. 2000, 39, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.-Q.; Qu, H. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jeon, S.; Kim, D. The impact of tour quality and tourist satisfaction on tourist loyalty: The case of Chinese tourists in Korea. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, M. Conducting Tours, 3rd ed.; Thomson Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0766814196. [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger, Y.; Steiner, C. Reconceptualising Interpretation: The Role of Tour Guides in Authentic Tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2006, 9, 481–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazaizeh, M.M.; Jamaliah, M.M.; Alzghoul, Y.A.; Mgonja, J.T. Tour Guide and Tourist Loyalty toward Cultural Heritage Sites: A Signaling Theory Perspective. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetıinkaya, M.Y.; Öter, Z. Role of tour guides on tourist satisfaction level in guided tours and impact on revisiting Intention: A research in Istanbul. Eur. J. Tour. Hosp. Recreat. 2016, 7, 40–54. [Google Scholar]

- Syakier, W.A.; Hanafiah, M.H. Tour Guide Performances, Tourist Satisfaction and Behavioural Intentions: A Study on Tours in Kuala Lumpur City Centre. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 23, 597–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Li, S.; Xu, J.; Liu, M.; Chen, G. Examining tour guide humor as a driver of tourists’ positive word of mouth: A comprehensive mediation model. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 1824–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Hsu, C.H.C.; Chan, A. Tour Guide Performance and Tourist Satisfaction: A Study of the Package Tours in Shanghai. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2009, 34, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Io, M.-U.; Hallo, L. A Comparative Study of Tour Guides’ Interpretation: The Case of Macao. Tour. Anal. 2012, 17, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, G.; Yarcan, S. The professional relationship between tour guides and tour operators. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Jahwari, D.S.; Sirakaya-Turk, E.; Altintas, V. Evaluating communication competency of tour guides using a modified importance-performance analysis (MIPA). Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabel, A.; Pearce, P.L. Highlighting the benefits of tourism humour: The views of tourists. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 16, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Io, M.-U. Testing a model of effective interpretation to boost the heritage tourism experience: A case study in Macao. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 900–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L. The dilemma of and countermeasures for the tour guide permission system in China. Tour. Trib. 2018, 33, 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, N.-T.; Cheng, Y.-S.; Chang, K.-C.; Chuang, L.-Y. The Asymmetric Effect of Tour Guide Service Quality on Tourist Satisfaction. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 19, 521–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Culture and Tourism, [Notice on Organizing and Implementing the 2023 National Tour Guide Qualification Examination by the Market Management Department of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism]. Available online: https://zwgk.mct.gov.cn/zfxxgkml/scgl/202307/t20230704_945598.html (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- Cheng, Y.-S.; Kuo, N.-T.; Chang, K.-C.; Chen, C.-H. How a Tour Guide Interpretation Service Creates Intention to Revisit for Tourists from Mainland China: The Mediating Effect of Perceived Value. J. China Tour. Res. 2018, 15, 84–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, S. Cultural influences on memorable tourism experiences. Anatolia 2019, 30, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. The Impact of Memorable Tourism Experiences on Loyalty Behaviors: The Mediating Effects of Destination Image and Satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2017, 57, 856–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagi, T.; Frenzel, F. Tourism and urban heritage in Kibera. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 92, 103325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Huang, L.; Xu, C.; He, K.; Shen, K.; Liang, P. Analysis of the Mediating Role of Place Attachment in the Link between Tourists’ Authentic Experiences of, Involvement in, and Loyalty to Rural Tourism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.F.; Li, Z.W. Destination authenticity, place attachment and loyalty: Evaluating tourist experiences at traditional villages. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 1–16. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13683500.2022.2153012 (accessed on 11 October 2022). [CrossRef]

- Bonn, M.A.; Joseph-Mathews, S.M.; Dai, M.; Hayes, S.; Cave, J. Heritage/Cultural Attraction Atmospherics: Creating the Right Environment for the Heritage/Cultural Visitor. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, B.; Black, R. The changing face of the tour guide: One-way communicator to choreographer to co-creator of the tourist experience. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2015, 40, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Preko, A.; Amoako, G.K.; Dzogbenuku, R.K.; Kosiba, J. Digital tourism experience for tourist site revisit: An empirical view from Ghana. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2022, 6, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Weiler, B.; Assaker, G. Effects of Interpretive Guiding Outcomes on Tourist Satisfaction and Behavioral Intention. J. Travel Res. 2014, 54, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Tian, J.; Kong, Y.; Gao, J. Impact of tour guide humor on tourist pro-environmental behavior: Utilizing the conservation of resources theory. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 25, 100728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Lin, M.-L.; Chen, Y.-C. How Tour Guides’ Professional Competencies Influence on Service Quality of Tour Guiding and Tourist Satisfaction: An Exploratory Research. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Stud. 2017, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X. Interpreting disaster: How interpretation types predict tourist satisfaction and loyalty to dark tourism sites. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 22, 100656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, N.-T.; Chang, K.-C.; Cheng, Y.-S.; Lin, J.-C. Effects of Tour Guide Interpretation and Tourist Satisfaction on Destination Loyalty in Taiwan’s Kinmen Battlefield Tourism: Perceived Playfulness and Perceived Flow as Moderators. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 33, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyitoğlu, F. Tourist Experiences of Guided Culinary Tours: The Case of Istanbul. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2020, 19, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.; Liang, Z.; Bao, J. The effect of tour interpretation on perceived heritage values: A comparison of tourists with and without tour guiding interpretation at a heritage destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 16, 100431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazaizeh, M.M.; Jamaliah, M.M.; Mgonja, J.T.; Ababneh, A. Tour guide performance and sustainable visitor behavior at cultural heritage sites. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1708–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrades, L.; Dimanche, F. Destination competitiveness in Russia: Tourism professionals’ skills and competences. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 910–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Ritchie, J.R.B.; McCormick, B. Development of a Scale to Measure Memorable Tourism Experiences. J. Travel Res. 2010, 51, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, C.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, C.; Huang, K. Psychological factors affecting memorable tourism experiences. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coudounaris, D.N.; Sthapit, E. Antecedents of memorable tourism experience related to behavioral intentions. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 1084–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Chandralal, L.; Rindfleish, J.; Valenzuela, F. An Application of Travel Blog Narratives to Explore Memorable Tourism Experiences. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 20, 680–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C. The role of the rural tourism experience economy in place attachment and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathisen, L. The Exploration of the Memorable Tourist Experience. In Advances in Hospitality and Leisure; Chen, S.J., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2012; Volume 8, pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Seyfi, S.; Rather, R.A.; Hall, C.M. Investigating the mediating role of visitor satisfaction in the relationship between memorable tourism experiences and behavioral intentions in heritage tourism context. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 687–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Noor, S.M.; Schuberth, F.; Jaafar, M. Investigating the effects of tourist engagement on satisfaction and loyalty. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 39, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.I.; Lim, X.-J.; Hall, C.M.; Tee, K.K.; Basha, N.K.; Ibrahim, W.S.N.B.; Koupaei, S.N. Time for Tea: Factors of Service Quality, Memorable Tourism Experience and in Sustainable Tea Loyalty Tourism Destination. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, O.C.; Cifci, I. Modeling self-identification, memorable tourism experience, overall satisfaction and destination loyalty: Empirical evidence from small island destinations. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2022, 6, 1001–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Wei, L.; Zhang, T. Impact of tourist experience on memorability and authenticity: A study of creative tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, J.E.; Ritchie, J.R.B. The service experience in tourism. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.; Guo, W.; Xiao, X.; Yan, M. The Relationship between Tour Guide Humor and Tourists’ Behavior Intention: A Cross-Level Analysis. J. Travel Res. 2019, 59, 1478–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irimiás, A.; Mitev, A.; Michalkó, G. The multidimensional realities of mediatized places: The transformative role of tour guides. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2020, 19, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.F.; Zhang, Y.; Quan, H. The relationship among food perceived value, memorable tourism experiences and behaviour intention: The case of the Macao food festival. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2020, 19, 258–268. [Google Scholar]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M.; Hatamifar, P. Understanding memorable tourism experiences and behavioural intentions of heritage tourists. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 21, 100621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, J.; Shaver, P.R. (Eds.) Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 1-57230-087-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.N.; Lee, C.; Chen, H.J. The relationship among tourists’ involvement, place attachment and interpretation satisfaction in Taiwan’s national parks. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapito, D.; Mendes, J.; Valle, P. Exploring the conceptualization of the sensory dimension of tourist experiences. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, D.J.; Jenkins, J.M. Appraisive images of tourist areas: Application of personal constructs. Aust. Geogr. 1993, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinanda, O.; Sari, A.Y.; Cerya, E.; Riski, T.R. Predicting place attachment through selfie tourism, memorable tourism experience and hedonic well-being. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2022, 8, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, E.; Björk, P.; Coudounaris, D.N.; Jiménez-Barreto, J. Memorable Halal Tourism Experience and Its Effects on Place Attachment. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2022, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, B.; Black, R. Tour Guiding Research. Insights, Issues and Implications; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1845414689. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, M.L.; Choi, Y.; Lee, C.K.; Ahmad, M.S. Effects of place attachment and image on revisit intention in an ecotourism destination: Using an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.Y.; Tsaur, S.H.; Yen, C.H.; Lai, H.R. Tour member fit and tour member–leader fit on group package tours: Influences on tourists’ positive emotions, rapport, and satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Prayag, G.; van der Veen, R.; Huang, S.; Deesilatham, S. Mediating Effects of Place Attachment and Satisfaction on the Relationship between Tourists’ Emotions and Intention to Recommend. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cardinale, S.; Nguyen, B.; Melewar, T.C. Place-based brand experience, place attachment and loyalty. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2016, 34, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, J. Antecedents and consequences of place attachment: A comparison of Chinese and Western urban tourists in Hangzhou, China. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.-K.; Kok, Y.-S.; Choon, S.-W. Sense of place and sustainability of intangible cultural heritage—The case of George Town and Melaka. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sable, P. What is adult attachment? Clin. Soc. Work. J. 2008, 36, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vada, S.; Prentice, C.; Hsiao, A. The influence of tourism experience and well-being on place attachment. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The measurement of place attachment: Validity and generalizability of a psychometric approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar]

- Kyle, G.; Graefe, A.; Manning, R. Testing the Dimensionality of Place Attachment in Recreational Settings. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, A.G.; Mowen, A.J.; Graefe, A.R. Predicting Intentions to Return to a Nature Center after an Interpretive Special Event. J. Interpret. Res. 2017, 22, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, S.M.; Ariyanto, H.H.; Kiumarsi, S. The effect of place attachment on visitors’ revisit intentions: Evidence from Batam. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 22, 51–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Chen, N.; Del Chiappa, G. Domestic tourists to Sardinia: Motivation, overall attitude, attachment, and behavioural intentions. Anatolia 2017, 29, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Xiong, Q.; Li, P.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.-E.; Ryan, C. Celebrity involvement and film tourist loyalty: Destination image and place attachment as mediators. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 54, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J. Nanxun Shengdian. Available online: https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&chapter=128946&remap=gb. (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Tsaur, S.-H.; Teng, H.-Y. Exploring tour guiding styles: The perspective of tour leader roles. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Muskat, B.; Del Chiappa, G. Understanding the relationships between tourists’ emotional experiences, perceived overall image, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Curtin, S. Managing the wildlife tourism experience: The importance of tour leaders. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 12, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 147 | 35.3 |

| Female | 269 | 64.7 | |

| Age | <25 | 79 | 19.0 |

| 25–35 | 152 | 36.5 | |

| 36–40 | 95 | 22.8 | |

| 41–45 | 53 | 12.7 | |

| >45 | 37 | 8.9 | |

| Education | Middle school | 43 | 10.34 |

| Junior college | 115 | 27.64 | |

| Undergraduate | 203 | 48.80 | |

| Postgraduate and above | 55 | 13.22 | |

| Travel companion | None | 14 | 3.37 |

| Family | 276 | 66.35 | |

| Other | 126 | 30.29 | |

| Number of visits | 1 | 318 | 76.44 |

| 2 | 69 | 16.59 | |

| 3 | 25 | 6.01 | |

| Above 3 | 4 | 0.96 | |

| Occupation | Civil servant | 11 | 2.64 |

| Enterprise employee | 233 | 56.01 | |

| Sole trader | 76 | 18.27 | |

| Teacher | 29 | 6.97 | |

| Farmer | 18 | 4.33 | |

| Student | 49 | 11.78 | |

| Total | 416 | 100 |

| Constructs | Measurement Items | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Tour guide cultural interpretation | 1. My tour guide will introduce the cultural background of tourist attractions in detail. | Tsaur and Teng, 2017 [89] |

| 2. My tour guide will encourage tour members to experience culture and be involved in local life. | ||

| 3. My tour guide will teach tour members about local languages. | ||

| 4. My tour guide will include local people, events, and objects in interpretations. | ||

| Memorable tourism experience | 1. I had a once-in-a-lifetime experience. | Vada et al., 2019 [80] |

| 2. I had a unique experience. | ||

| 3. My trip was different from previous trips. | ||

| 4. I experienced something new. | ||

| Place attachment | 1. I feel that this place is a part of me. | Vada et al., 2019 [80] |

| 2. This place is the best place for what I like to do. | ||

| 3. This place is very special to me. | ||

| 4. No other place can compare to this place. | ||

| Revisit intention | 1. I would revisit this place in the future. | Bonn et al., 2007 [37] |

| 2. If given the opportunity, I would return to this place. | ||

| 3. I am loyal to this cultural destination. | ||

| Intention to recommend | 1. I would recommend this place to my friends. | Bonn et al., 2007 [37] |

| 2. I would say positive things about this place. | ||

| 3. I would encourage friends and relatives to visit this place. |

| Variables | Codes | Rotated Component Matrix | Cronbach’s Alpha | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Tour guide’s cultural-oriented interpretation | TCI1 | 0.088 | 0.890 | 0.066 | −0.004 | 0.082 | 0.896 |

| TCI2 | 0.054 | 0.832 | 0.075 | 0.026 | 0.056 | ||

| TCI3 | 0.095 | 0.885 | 0.030 | 0.013 | 0.056 | ||

| TCI4 | 0.061 | 0.855 | 0.070 | −0.013 | 0.078 | ||

| Memorable tourism experience | MTE1 | 0.887 | 0.072 | 0.071 | 0.066 | 0.084 | 0.917 |

| MTE2 | 0.875 | 0.082 | 0.057 | 0.092 | 0.132 | ||

| MTE3 | 0.859 | 0.079 | 0.037 | 0.116 | 0.142 | ||

| MTE4 | 0.886 | 0.081 | 0.084 | 0.067 | 0.119 | ||

| Place attachment | PA1 | 0.059 | 0.077 | 0.861 | 0.025 | 0.126 | 0.869 |

| PA2 | 0.035 | 0.081 | 0.840 | 0.068 | 0.047 | ||

| PA3 | 0.033 | 0.047 | 0.790 | 0.079 | 0.200 | ||

| PA4 | 0.110 | 0.038 | 0.850 | 0.096 | −0.001 | ||

| Revisit intention | RI1 | 0.152 | 0.070 | 0.097 | 0.060 | 0.902 | 0.914 |

| RI2 | 0.163 | 0.101 | 0.112 | 0.083 | 0.893 | ||

| RI3 | 0.133 | 0.095 | 0.145 | 0.040 | 0.895 | ||

| Intention to recommend | IR1 | 0.110 | −0.020 | 0.098 | 0.926 | 0.070 | 0.930 |

| IR1 | 0.095 | 0.023 | 0.073 | 0.913 | 0.061 | ||

| IR1 | 0.102 | 0.014 | 0.086 | 0.936 | 0.046 | ||

| Eigen Value (Rotated) | 3.215 | 3.063 | 2.891 | 2.633 | 2.559 | ||

| Explained Variance (%) | 17.860 | 17.015 | 16.059 | 14.628 | 14.215 | ||

| Cumulative Variance (%) | 17.860 | 34.874 | 50.993 | 65.561 | 79.776 | ||

| KMO = 0.828; Bartlett = 5052.719; Sig = 0.000; df = 153 | |||||||

| Variables | Codes | Unstd. | S.E. | Z | p | Std. | Cronbach’s Alpha | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tour guide’s cultural-oriented interpretation | TCI4 | 1 | 0.813 | 0.896 | 0.686 | 0.897 | |||

| TCI3 | 1.032 | 0.052 | 19.72 | *** | 0.853 | ||||

| TCI2 | 0.916 | 0.054 | 17.084 | *** | 0.764 | ||||

| TCI1 | 1.081 | 0.053 | 20.407 | *** | 0.879 | ||||

| Memorable tourism experience | MTE4 | 1 | 0.872 | 0.917 | 0.734 | 0.917 | |||

| MTE3 | 0.99 | 0.045 | 21.795 | *** | 0.836 | ||||

| MTE2 | 0.986 | 0.043 | 22.817 | *** | 0.859 | ||||

| MTE1 | 0.969 | 0.042 | 22.863 | *** | 0.86 | ||||

| Place attachment | PA4 | 1 | 0.798 | 0.869 | 0.626 | 0.870 | |||

| PA3 | 0.91 | 0.059 | 15.531 | *** | 0.742 | ||||

| PA2 | 1.03 | 0.062 | 16.495 | *** | 0.782 | ||||

| PA1 | 1.061 | 0.06 | 17.72 | *** | 0.84 | ||||

| Revisit intention | RI3 | 1 | 0.882 | 0.914 | 0.780 | 0.914 | |||

| RI2 | 0.989 | 0.041 | 24.142 | *** | 0.886 | ||||

| RI1 | 0.98 | 0.041 | 24.016 | *** | 0.882 | ||||

| Intention to recommend | IR3 | 1 | 0.932 | 0.930 | 0.818 | 0.931 | |||

| IR2 | 0.894 | 0.033 | 26.732 | *** | 0.865 | ||||

| IR1 | 0.975 | 0.032 | 30.018 | *** | 0.915 | ||||

| χ2 = 160.249, DF = 125, χ2/DF = 1.282, RMSEA = 0.026, GFI = 0.960, IFI = 0.993, TLI = 0.991, CFI = 0.993 | |||||||||

| Note: *** p < 0.000. | |||||||||

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCI | 0.828 | ||||

| MTE | 0.186 ** | 0.856 | |||

| PA | 0.154 ** | 0.165 ** | 0.791 | ||

| RI | 0.194 ** | 0.311 ** | 0.255 ** | 0.883 | |

| IR | 0.032 | 0.217 ** | 0.183 ** | 0.156 ** | 0.904 |

| Mean | 3.201 | 3.267 | 3.365 | 3.343 | 3.982 |

| Std. Deviation | 0.998 | 0.976 | 1.023 | 0.959 | 1.007 |

| Hypothesis | Standardized Estimate | Unstandardized Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a TCI→RI | 0.12 | 0.116 | 0.05 | 2.321 | 0.02 | Supported |

| H1b TCI→IR | −0.039 | −0.041 | 0.056 | −0.73 | 0.465 | Not Supported |

| H2 TCI→MTE | 0.207 | 0.202 | 0.053 | 3.85 | *** | Supported |

| H3a MTE→RI | 0.276 | 0.272 | 0.052 | 5.254 | *** | Supported |

| H3b MTE→IR | 0.21 | 0.226 | 0.058 | 3.902 | *** | Supported |

| H5 MTE→PA | 0.158 | 0.164 | 0.058 | 2.846 | 0.004 | Supported |

| H6 TCI→PA | 0.139 | 0.141 | 0.057 | 2.492 | 0.013 | Supported |

| H7a PA→RI | 0.211 | 0.201 | 0.051 | 3.971 | *** | Supported |

| H7b PA→IR | 0.168 | 0.174 | 0.057 | 3.071 | 0.002 | Supported |

| χ2 = 160.249, DF = 125, χ2/DF = 1.282, RMSEA = 0.026, GFI = 0.960, IFI = 0.993, TLI = 0.991, CFI = 0.993 | ||||||

| Hypothesized Path | Estimate | S.E. | Bias-Corrected 95%CI | Percentile 95%CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | p | Lower | Upper | p | |||

| TCI→MTE→RI (H4a) | 0.055 | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.108 | 0.000 | 0.019 | 0.102 | 0.001 |

| TCI→MTE→IR (H4b) | 0.046 | 0.018 | 0.017 | 0.091 | 0.001 | 0.014 | 0.083 | 0.002 |

| TCI→PA→RI (H8a) | 0.028 | 0.016 | 0.005 | 0.070 | 0.015 | 0.003 | 0.066 | 0.025 |

| TCI→PA→IR (H8b) | 0.025 | 0.015 | 0.004 | 0.065 | 0.016 | 0.001 | 0.060 | 0.033 |

| TCI→MTE→PA→RI (H9a) | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.019 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.015 | 0.008 |

| TCI→MTE→PA→IR (H9b) | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.018 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.015 | 0.016 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, L.; Ma, J.-Y.; Ann, C.-O. Exploring the Effect of Tour Guide Cultural Interpretation on Tourists’ Loyalty in the Context of the Southern Journey by Emperor Qianlong. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11585. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511585

Shi L, Ma J-Y, Ann C-O. Exploring the Effect of Tour Guide Cultural Interpretation on Tourists’ Loyalty in the Context of the Southern Journey by Emperor Qianlong. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11585. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511585

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Lei, Jing-Yan Ma, and Chul-Ok Ann. 2023. "Exploring the Effect of Tour Guide Cultural Interpretation on Tourists’ Loyalty in the Context of the Southern Journey by Emperor Qianlong" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11585. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511585

APA StyleShi, L., Ma, J.-Y., & Ann, C.-O. (2023). Exploring the Effect of Tour Guide Cultural Interpretation on Tourists’ Loyalty in the Context of the Southern Journey by Emperor Qianlong. Sustainability, 15(15), 11585. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511585