Circular Business Model Value Dimension Canvas: Tool Redesign for Innovation and Validation through an Australian Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

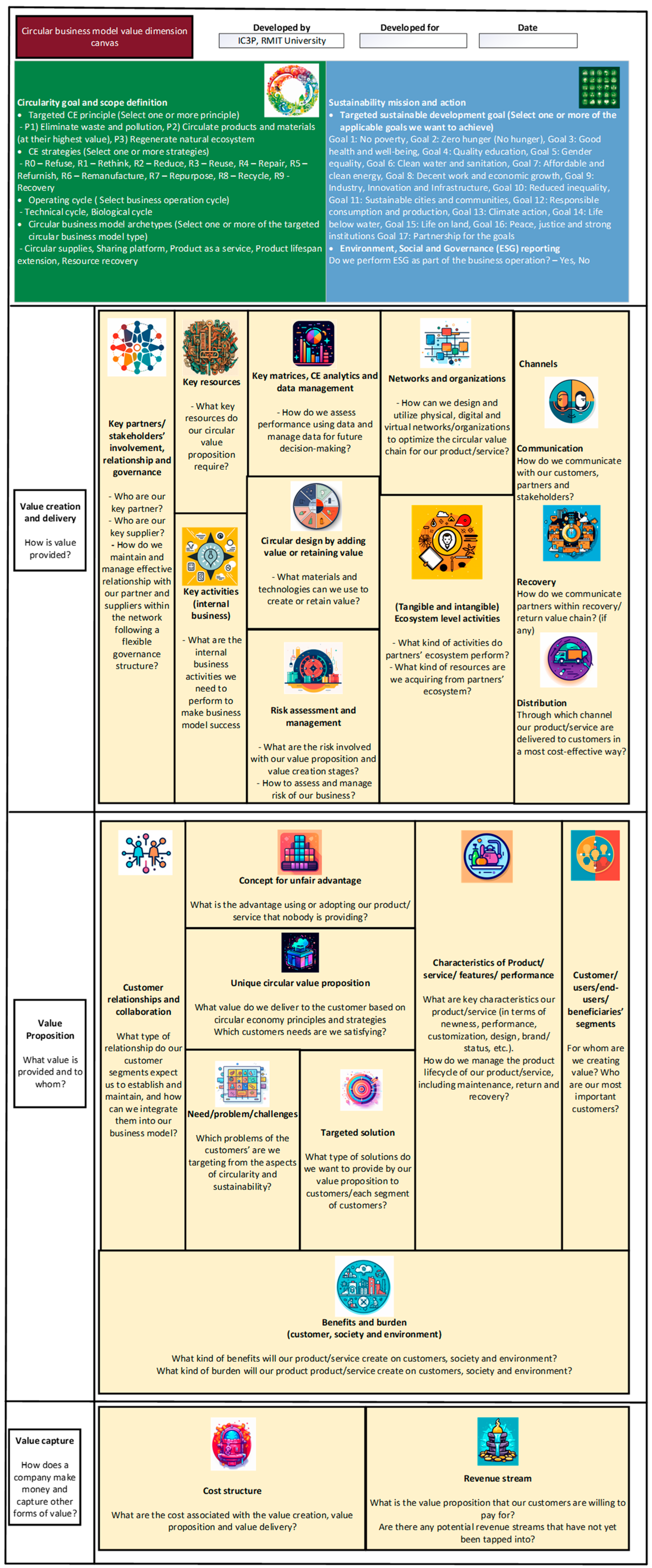

2. Literature Review

2.1. Circular Economy

2.2. Circular Business Model

2.3. Theories in CBM

2.4. Canvas and Framework-Based CBMI Tools

2.4.1. Architecture and Building Blocks of the Selected Tools and Frameworks

2.4.2. Sustainability and Circularity Aspects in CBM

2.5. Social Enterprise and CBM

2.6. Australian Context of CBM

3. Circular Business Model Value Dimension Canvas—Development and Characterization of Building Blocks

4. Methodology

5. Results

5.1. Company X—Social Enterprise (Hybrid CBM—Resource Recovery, Sharing Platform and Product Lifespan Extension)

5.2. Circularity and Sustainability at Company X

5.3. Value Creation and Delivery

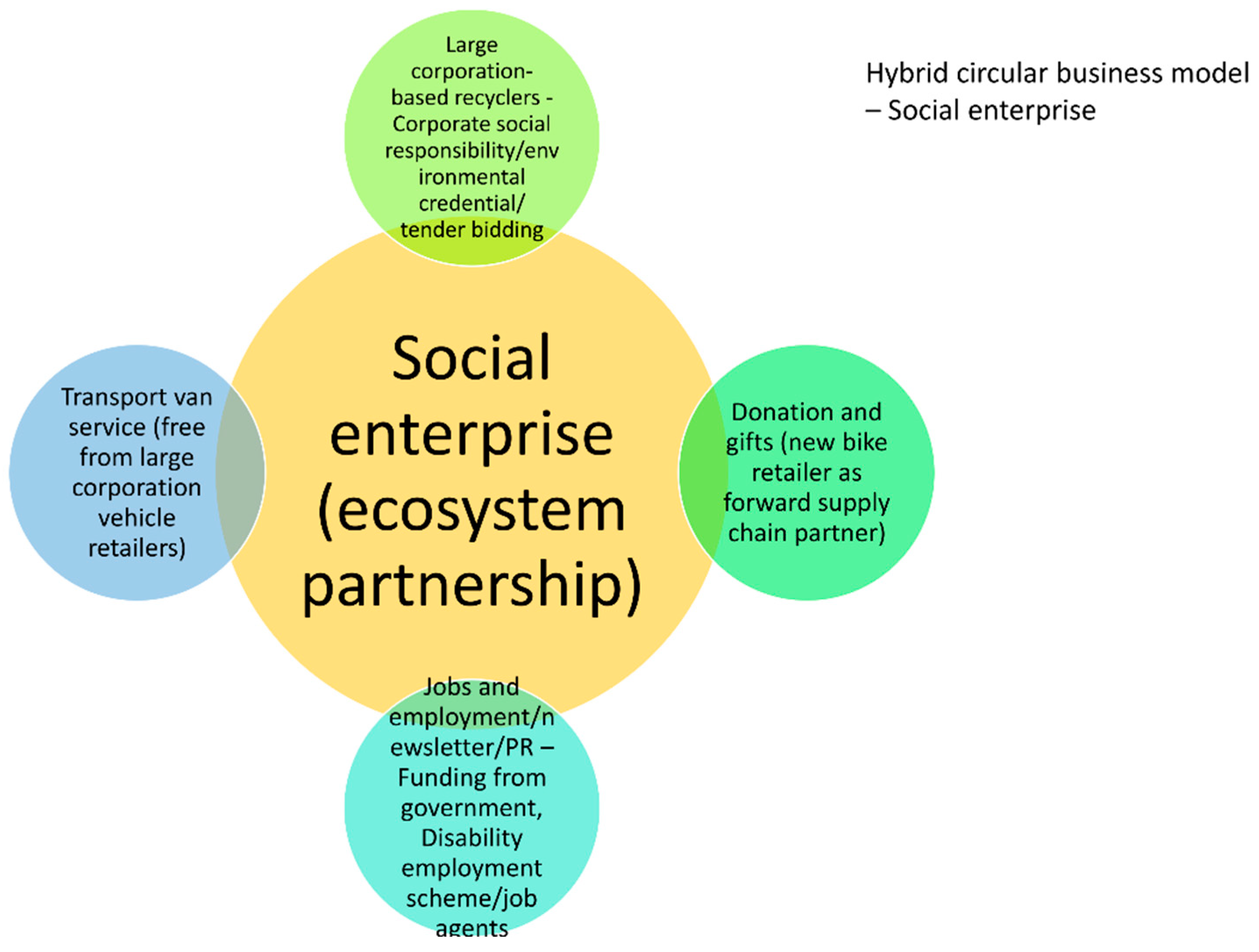

5.3.1. Key Partners/Stakeholders’ Involvement, Relationship, and Governance

5.3.2. Key Resources

5.3.3. Key Activities (Internal Business)

5.3.4. Key Matrices, CE Analytics, and Data Management

5.3.5. Circular Design by Adding Value or Retain Value

5.3.6. Risk Assessment and Management

- -

- There is a lack of awareness and culture regarding the value of waste, which may present difficulties when attempting to attract consumers.

- -

- The company confronts unbalanced competition from retailers that sell cheaper bicycles.

- -

- In addition, they emphasized the need for an unpredictably continuous supply of economically viable inputs, such as used bicycles.

- -

- Furthermore, the cost of repairing bicycles sourced from diverse channels and the difficulty of regulating the supply chain were identified as potential risks.

- -

- Inadequate sales and reliance on an uncertain workforce, especially trainees who may pursue conventional employment, were also cited as causes for concern.

5.3.7. Networks and Organizations

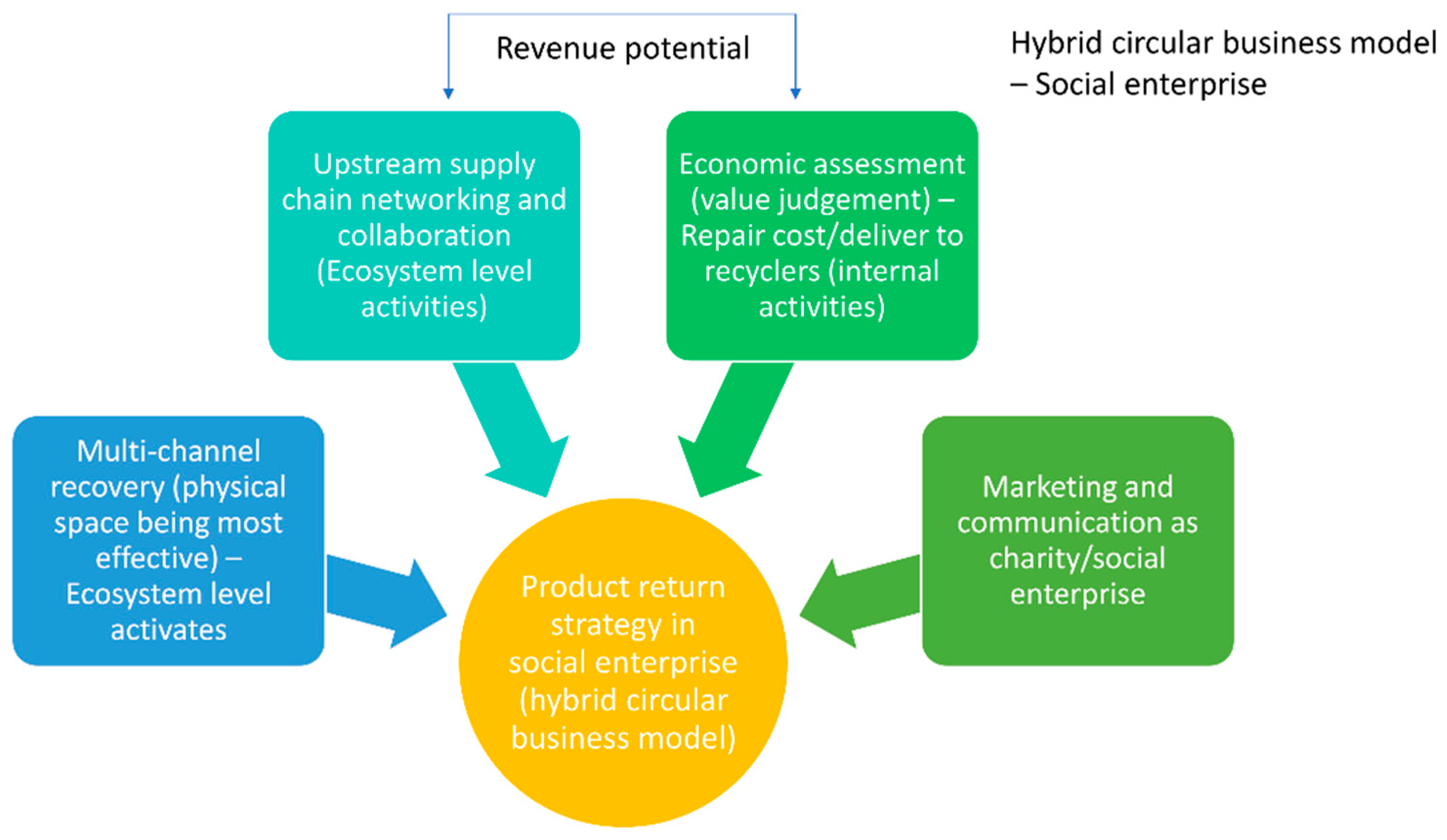

5.3.8. (Tangible and Intangible) Ecosystem Level Activities

5.3.9. Channel

Communication

Recovery

Distribution

5.4. Value Proposition

5.4.1. Customer Relationships and Collaboration

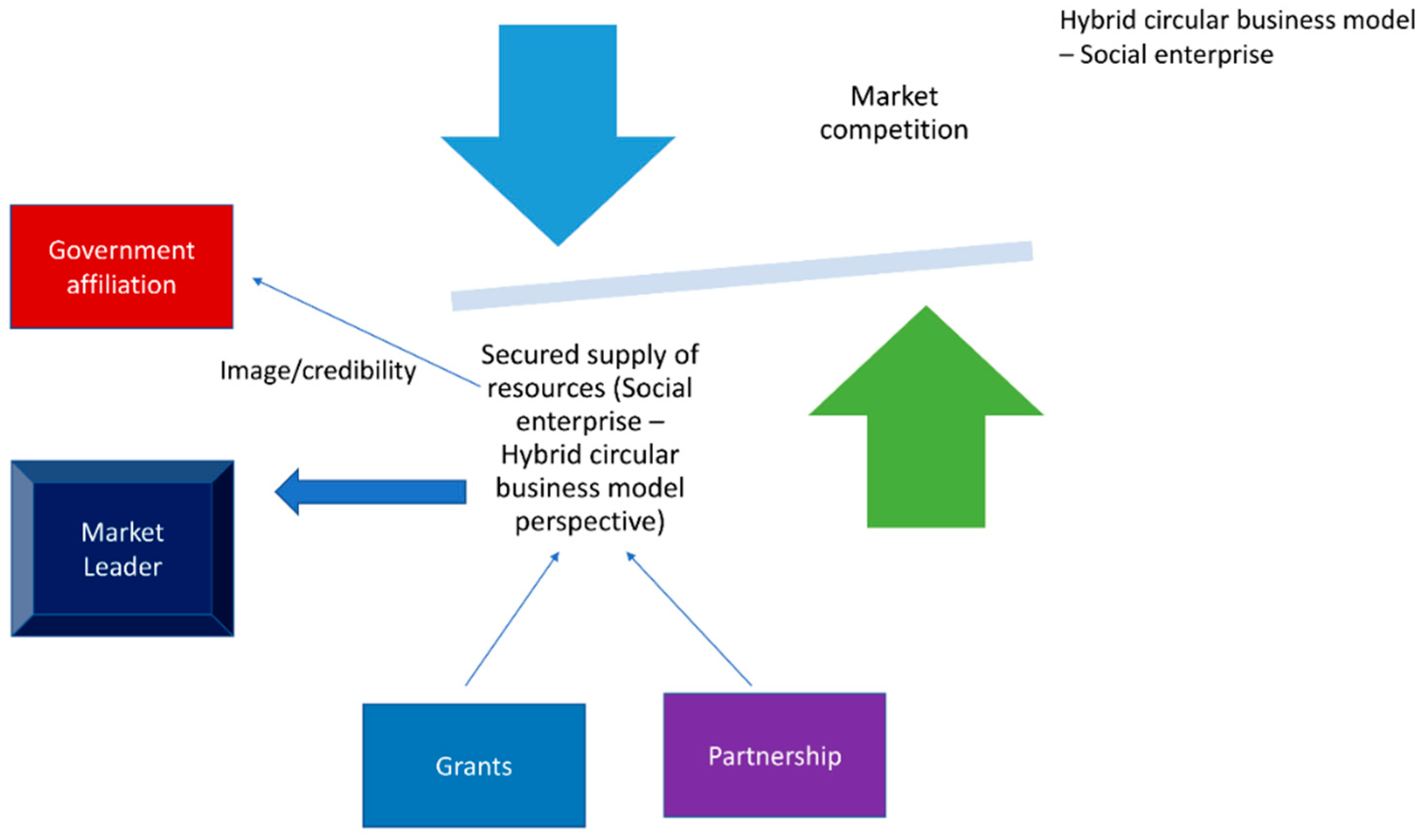

5.4.2. Concept for Unfair Advantage

5.4.3. A Unique Circular Value Proposition

5.4.4. Needs/Problems/Challenges

5.4.5. Targeted Solutions

5.4.6. Characteristics of Product/Service/Features/Performance

5.4.7. Customer/Users/End-Users/Beneficiaries Segments

5.4.8. Benefits and Burden (Customer, Society, and Environment)

5.5. Value Capture

5.5.1. Cost Structure

5.5.2. Revenue Stream

6. Discussion

6.1. Methodological and Canvas Design Perspectives

6.2. Theoretical Perspectives

6.3. Circular Social Entrepreneurship and Business Models

6.4. Contextual Factors of Hybrid Business Model—Focusing on Social Enterprise

6.4.1. Synergic Partnership and Collaboration

6.4.2. Dynamics Capabilities and Business Resilience

6.4.3. Critical Resources Base for Success

6.4.4. Organizational and Operational Risks

6.4.5. Circular Product Design and Product Lifecycle Management

6.4.6. Data Management and Performance Enhancement

6.4.7. Institution and Infrastructural Support for Market Leadership

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Value Dimension | Building Block | Origin/Background |

|---|---|---|

| Circular economy goal and scope definition | This block tends to identify user’s circularity goals and associated R-strategies [7] tend to implement in their business model. It also identifies operating cycle and potential CBM types [11]. | |

| Sustainability mission and action | Sustainable development goals described by United Nations [87] and environmental performance and sustainability consideration within circular business from the context of environmental, social, and governance (ESG). ESG inclusion is not a prominent approach within CBM. Previously, Fatimah et. al. [60] focused on ESG from the lens of e-business model. | |

| Value creation and delivery | Key partners/stakeholders’ involvement, relationship, and governance | This block is inspired originally by Osterwalder and Pigneur [3]’s BMC and the building block of “Key partners”. Further modification was made to include the aspects of relationship, involvement, and governance-related aspects in one single place. Previously, stakeholder relationship is being mentioned by Daou et al. [20], while stakeholder involvement by Maria and Katri [42]. The governance-related aspects were drawn from “Social stakeholder Business Model Canvas” by Joyce and Paquin [18]. |

| Key resources | This block is inspired originally from Osterwalder and Pigneur [3]’s BMC and the building block of “Key partners”. In addition to that tangible and intangible resources mentioned by Lauten-Weiss and Ramesohl [40] are also compiled in this building block. Service and infrastructure-related aspects are also included mentioned by Scheepens et al. [88]. | |

| Key activities (internal business) | Key internal business activities such as procurement, maintenance, staffing, and others come under these aspects keeping in mind the R-strategies and CE principles. Supplier outsourcing-related aspects are also included mentioned by Joyce and Paquin [18] in their environmental life cycle layer of the triple-layered business model canvas. | |

| Key matrices, CE analytics and data management | This “Key matric” was a building block of [39] by which a business can assess its performance. In [40], authors mentioned CE analytics. Kozlowski, Searcy, and Bardecki [38] highlighted data management aspects in their (re)Design canvas. All these aspects were taken into consideration for the block. This should be considered a powerhouse of knowledge and information by which business can assess their performance. | |

| Circular design by adding value or retain value | Value recovery, retain value, optimal use circular design, described by Achterberg, Hinfelaar, and Bocken [34] were comprehensively represented via this block. Circular design-related aspects were also mentioned by Lauten-Weiss and Ramesohl [40]. | |

| Risk assessment and management | This building block was inspired by Wit and Pylak [24] who previously focused on reverse logistics only and this is generalized identifying various types of risks such as supply risk, unexpected policy and regulation, volatile market environment, unstable material and energy price, workforce shortage and others. | |

| Networks and organizations | This block is inspired from the Achterberg, Hinfelaar and Bocken [34]’s value hill. Furthermore, concept of circular business network and circular business network relationships were also included illustrated by Hofmann, Marwede, Nissen and Lang [17]. | |

| (Tangible and intangible) ecosystem level activities | Inspired from Osterwalder and Pigneur [3]’s BMC but later included with the aspects mentioned by [40]. However, [40] did not mentioned it as part of the activities, which is revised in this canvas. Value co-creation and co-destruction aspects should also be considered under the block mentioned by [28] | |

| Channel—Communication | This building block is inspired from Daou, Mallat, Chammas, Cerantola, Kayed and Saliba [20] and Hamwi, Lizarralde and Legardeur [16] who identified associated building block communication and sales and communication channel, respectively. | |

| Channel—Recovery | Take-back aspects particular mentioned by [19], while Maria and Katri [42] highlighted reverse logistics issues. From there, this block is inspired. | |

| Channel—Distribution | Channel was mentioned by Maurya [39] and Osterwalder and Pigneur [3] highlighting the forward distribution channel. | |

| Customer relationships and collaboration | Originally inspired from Osterwalder and Pigneur [3] which was later modified by Maria and Katri [42] as customer relationship and collaboration which is directly included as a building block in the canvas. | |

| Concept for unfair advantage | Inspired from the lean canvas by Maurya [39]. | |

| Value proposition (what value is provided and to whom?) | Unique circular value proposition | Value proposition is one of the core components of almost all the canvases. The original is from Osterwalder and Pigneur [3] which was later modified by several authors. |

| Need/problem/challenges | “Problem” as a building block was mentioned by [39], which was later changed by [20]. Logically, this block should be started by a business while using the canvas described in this study. | |

| Targeted solution | Solutions was mentioned by [39]. | |

| Characteristics of Product/service/features/performance | Inspired from the building blocks of characteristics of product service portfolio [46], service [88], product flexibility [16], service attribute [16], functional value [18]. However, the block proposed in the canvas has not been explicitly mentioned in any of the canvases. | |

| Customer/users/end-users/beneficiaries segments | Inspired from Osterwalder and Pigneur [3] called it as “Customer segment”. Several authors then modified it according to the needs. For example, beneficiaries [54], users and customers [89]. All these aspects are consolidated in this block. | |

| Benefits and burden (customer, society, and environment) | Sustainability impacts (sustainability benefits) [42], environmental benefits [18], social benefits [18] and benefits and burden [15] were some of the inspirations developing the building block. | |

| Value capture | Cost structure | Inspired from Osterwalder and Pigneur [3]. |

| Revenue stream | Inspired from Osterwalder and Pigneur [3]. |

| Value Dimension | Building Block | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Circular economy goal and scope definition | This block tends to identify users’/businesses’ circularity goals and intended R-strategies to be implemented in their organization, along with potential scope in terms of business operating cycle and alignment with CBM archetypes. | |

| Sustainability mission and action | Users will define their overarching sustainable development goals and their intention/plan for ESG reporting at present/in future. | |

| Value creation and delivery | Key partners/stakeholders’ involvement, relationship, and governance | This block encompasses all associated aspects of making business processes operational with the context of CE, CBM and circular supply chain concerning business partners, stakeholders, and the relationship among the actors. |

| Key resources | This block represents the resources require to create the circular value proposition and aspects required to be a market leader. | |

| Key activities (internal business) | Key internal business activities such as procurement, maintenance, staffing, and others come under these aspects keeping in mind the R-strategies and CE principles. | |

| Key matrices, CE analytics and data management | Performance assessment is a critical task for both large and small businesses. CE analytics, key metrics, and data management systems have become integral part where state-of-the-art technologies such as IoT, could computing is utilized for product as a service model. That is also true for resource recovery-type business models where resource hotspots, material flow, landfill avoidance, and reduced material use are some of the key performance parameters that could be used by a business. | |

| Circular design by adding value or retain value | In addition to value recovery, retaining value, optimal use by circular design, materials, and technologies required to create or retain such value is also included in this building block. Resource strategies (e.g., slowing, closing, regenerating, narrowing resource loop) are closely connected with the circular design and particular method of transformation which should be defined in this building block. Value retention and value addition could be two of the potential ways of value creation. In such aspect, material and technology play critical roles in selecting specific objective-driven paths (i.e., are we going to use existing technology or go for new technology and material development?) | |

| Risk assessment and management | This block represents the associated risk and potential mitigation measures against those risk for a business. Early identification of the potential market risk for commercialization as well as operational or any kind of financial risk could better help devising strategies around value creation. Risk management strategy both at internal business level and at ecosystem level could further be assessed and monitored as part of the business model innovation process. | |

| Networks and organizations | It defines a distinct set of entity that could help businesses move fast forward both in terms of providing funding support, startup inclusion and providing necessary contacts and innovation opportunity both at technological level as well as advisory level. These could be non-government, government organizations and their associated network that help business accelerate in their innovation process. Business association, CE business hub, circular platform, (regional) innovation hub could be some of the examples about that. | |

| (Tangible and intangible) ecosystem level activities | Business activities associated with the ecosystem should be mentioned here. This block is separated from the key internal activities as at ecosystem level activities, co-design/co-creation effort should be required. Material and informational exchange, supply chain activities are associated with the block. Here material could be tangible and information as intangible, thus this block is referred to as (tangible and intangible) ecosystem level activities. | |

| Channel—Communication | Communication both with customers and business stakeholders is an essential part of the value creation process. Motivating customers to return their used items in a return scheme or operational feedback via third party are some of the examples. This block would define communication strategy of a business across the supply chain partners including customers for the purpose of value creation. | |

| Channel—Recovery | In various types of business models, reverse supply chain is the main aspect, and it creates value to a business. That is why recovery channel was identified as critical component under channel. | |

| Channel—Distribution | This block represents the forward supply and distribution related channels. | |

| Customer relationships and collaboration | It focuses on involving customers and nurturing collaboration throughout the value chain to drive innovation and loyalty. By adopting a customer-centric and collaborative strategy, businesses can foster innovation, increase customer loyalty, and expedite the shift towards circular and sustainable practices. | |

| Concept for unfair advantage | It emphasizes the development of a unique proposition that sets a company apart in the circular economy, fostering innovation, differentiation, and collaboration. | |

| Value proposition (what value is provided and to whom?) | Unique circular value proposition | It highlights the importance of providing distinctive solutions that incorporate circular principles, positioning businesses as leaders in the circular economy. |

| Need/problem/challenges | This block emphasizes the identification and understanding of market, societal, and environmental needs, problems, and challenges to drive the development of innovative circular solutions. | |

| Targeted solution | It emphasizes the development of targeted solutions that resolve identified needs, problems, and challenges while embracing circular principles. By incorporating circularity into product design, business models, technologies, and collaborations, businesses can develop solutions that promote resource efficiency, waste reduction, and overall sustainability. | |

| Characteristics of Product/service/features/performance | This block emphasizes the need to define and accentuate the attributes that make the offering sustainable, circular, and competitive. Businesses can differentiate themselves and contribute to a more sustainable and circular future by integrating characteristics such as sustainable materials, durability, closed-loop design, energy efficiency, and superior performance. Product lifecycle perspective particularly important in this block. | |

| Customer/users/end-users/beneficiaries segments | This block emphasizes the significance of identifying and comprehending the distinct categories of customers, users, or beneficiaries who will derive value from the circular offering. Businesses can drive the adoption of sustainable and circular practices by conducting extensive market research, segmenting the target audience, and customizing the circular solution to suit the needs of each segment. | |

| Benefits and burden (customer, society, and environment) | It focuses on assessing and understanding the impacts of a circular business model on customers, society, and the environment. It involves evaluating the positive outcomes and advantages that the model brings to customers, such as enhanced product value, improved user experiences, and increased access to sustainable solutions. Additionally, the building block addresses the potential burdens or challenges that may arise, including the need for behaviour change, higher upfront costs, or adjustments in existing systems and processes. Triple bottom lines are integrated in this block which then connected with the circular goal and scope definition and sustainability mission and action building block. Other forms of value capture can be considered as part of the benefits in this block. | |

| Value capture | Cost structure | Understanding and managing the costs associated with implementing circular practices constitutes the “Cost Structure”. It is necessary to consider both traditional and additional costs associated with the transition to a circular model. |

| Revenue stream | The “Revenue Stream” building block entails identifying and developing revenue sources that align with circular and sustainable practices. |

| Value Dimension | Building Block | Key Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Circular economy goal and scope definition |

| |

| Sustainability mission and action |

| |

| Value creation and delivery | Key partners/stakeholders’ involvement, relationship, and governance |

|

| Key resources |

| |

| Key activities (internal business) |

| |

| Key matrices, CE analytics and data management |

| |

| Circular design by adding value or retain value |

| |

| Risk assessment and management |

| |

| Networks and organizations |

| |

| (Tangible and intangible) Ecosystem level activities |

| |

| Channel—Communication |

| |

| Channel—Recovery |

| |

| Channel—Distribution |

| |

| Customer relationships and collaboration |

| |

| Concept for unfair advantage |

| |

| Value proposition (what value is provided and to whom?) | Unique circular value proposition |

|

| Need/problem/challenges |

| |

| Targeted solution |

| |

| Characteristics of product/service/features/performance |

| |

| Customer/users/end-users/beneficiaries segments |

| |

| Benefits and burden (customer, society, and environment) |

| |

| Value capture | Cost structure |

|

| Revenue stream |

|

References

- Pieroni, P.P.; McAloone, C.; Pigosso, C.A. Configuring New Business Models for Circular Economy through Product–Service Systems. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Pieroni, M.P.; Pigosso, D.C.; Soufani, K. Circular business models: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador, R.; Barros, M.V.; Freire, F.; Halog, A.; Piekarski, C.M.; De Francisco, A.C. Circular economy strategies on business modelling: Identifying the greatest influences. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 299, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the circular economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2013, 2, 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potting, J.; Hekkert, M.P.; Worrell, E.; Hanemaaijer, A. Circular Economy: Measuring Innovation in the Product Chain; Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ekins, P.; Domenech Aparisi, T.; Drummond, P.; Bleischwitz, R.; Hughes, N.; Lotti, L. The Circular Economy: What, Why, How and Where. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/regionaldevelopment/Ekins-2019-Circular-Economy-What-Why-How-Where.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Bocken, N.M.; De Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; Van Der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konietzko, J.; Bocken, N.; Hultink, E.J. Circular ecosystem innovation: An initial set of principles. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordic Innovation. Circular Business Models in the Nordic Manufacturing Industry. Available online: http://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1738958/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Rosenbloom, R.S. The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: Evidence from Xerox Corporation’s technology spin-off companies. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2002, 11, 529–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giourka, P.; Sanders, M.W.; Angelakoglou, K.; Pramangioulis, D.; Nikolopoulos, N.; Rakopoulos, D.; Tryferidis, A.; Tzovaras, D. The smart city business model canvas—A smart city business modeling framework and practical tool. Energies 2019, 12, 4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardeal, G.; Höse, K.; Ribeiro, I.; Götze, U. Sustainable business models–canvas for sustainability, evaluation method, and their application to additive manufacturing in aircraft maintenance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamwi, M.; Lizarralde, I.; Legardeur, J. Demand response business model canvas: A tool for flexibility creation in the electricity markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 282, 124539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, F.; Marwede, M.; Nissen, N.; Lang, K. Circular added value: Business model design in the circular economy. In PLATE: Product Lifetimes and the Environment; IOS Press: Tepper Drive Clifton, VA, USA, 2017; pp. 171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, A.; Paquin, R.L. The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1474–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, M. Designing the business models for circular economy—Towards the conceptual framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daou, A.; Mallat, C.; Chammas, G.; Cerantola, N.; Kayed, S.; Saliba, N.A. The Ecocanvas as a business model canvas for a circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, J.; Osmani, M.; Grubnic, S.; Díaz, A.I.; Grobe, K.; Kaba, A.; Ünlüer, Ö.; Panchal, R. Implementing a circular economy business model canvas in the electrical and electronic manufacturing sector: A case study approach. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 2023, 36, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okorie, O.; Charnley, F.; Russell, J.; Tiwari, A.; Moreno, M. Circular business models in high value manufacturing: Five industry cases to bridge theory and practice. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2021, 30, 1780–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nußholz, J.L. Circular business models: Defining a concept and framing an emerging research field. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wit, B.; Pylak, K. Implementation of triple bottom line to a business model canvas in reverse logistics. Electron. Mark. 2020, 30, 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurucz, E.C.; Colbert, B.A.; Luedeke-Freund, F.; Upward, A.; Willard, B. Relational leadership for strategic sustainability: Practices and capabilities to advance the design and assessment of sustainable business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N. Conceptual framework for shared value creation based on value mapping. In Proceedings of the Global Cleaner Production Conference, Sitges, Barcelona, 1–4 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Basile, V.; Capobianco, N.; Vona, R. The usefulness of sustainable business models: Analysis from oil and gas industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1801–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoveskog, M.; Halila, F.; Mattsson, M.; Upward, A.; Karlsson, N. Education for Sustainable Development: Business modelling for flourishing. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 4383–4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Schuit, C.S.C.; Kraaijenhagen, C. Experimenting with a circular business model: Lessons from eight cases. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 28, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahdari, A.; Sepasi, S.; Moradi, M. Achieving sustainability through Schumpeterian social entrepreneurship: The role of social enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P.; Baldassarre, B.; Konietzko, J.; Bocken, N.; Balkenende, R. A tool for collaborative circular proposition design. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Chea, R.; Vimalnath, P.; Bocken, N.; Tietze, F.; Eppinger, E. Integrating intellectual property and sustainable business models: The SBM-IP canvas. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achterberg, E.; Hinfelaar, J.; Bocken, N. Master Circular Busienss with the Value Hill. Available online: https://assets.website-files.com/5d26d80e8836af2d12ed1269/5dea74fe88e8a5c63e2c7121_finance-white-paper-20160923.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Rana, P.; Short, S.W. Value mapping for sustainable business thinking. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2015, 32, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Vladimirova, D.; Evans, S. Sustainable business model innovation: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.; Strupeit, L.; Whalen, K.; Nußholz, J. A review and evaluation of circular business model innovation tools. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, A.; Searcy, C.; Bardecki, M. The reDesign canvas: Fashion design as a tool for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, A. Running Lean: Iterate from Plan A to a Plan That Works; O’Reill y Media Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lauten-Weiss, J.; Ramesohl, S. The Circular Business Framework for Building, Developing and Steering Businesses in the Circular Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballie, J.; Woods, M. Circular by Design: A Model for Engaging Fashion/Textile SMEs with Strategies for Designed Reuse; Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.: Bingley, UK, 2018; pp. 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Antikainen, M.; Valkokari, K. A Framework for Sustainable Circular Business Model Innovation. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2016, 6, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuit, C.; Baldassarre, B.; Bocken, N. Sustainable business model experimentation practices: Evidence from three start-ups. In PLATE: Product Lifetimes and the Environment; IOS Press: Tepper Drive Clifton, VA, USA, 2017; pp. 370–376. [Google Scholar]

- Donner, M.; Radić, I.; Erraach, Y.; El Hadad-Gauthier, F. Implementation of Circular Business Models for Olive Oil Waste and By-Product Valorization. Resources 2022, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, J.M.E.; Gallego-Schmid, A.; Azapagic, A. Building a business case for implementation of a circular economy in higher education institutions. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, J.M.F.; Sharmina, M.; Gallego-Schmid, A.; Heyes, G.; Azapagic, A. Integrating Backcasting and Eco-Design for the Circular Economy: The BECE Framework. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 526–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Stijn, A.; Gruis, V. Towards a circular built environment: An integral design tool for circular building components. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2020, 9, 635–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Worksheet-Business Model Canvas. Available online: https://emf.thirdlight.com/link/tzb3y1er2tg1-iebwi8/@/preview/1?o (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Mentink, B. Circular Business Model Innovation: A Process Framework and a Tool for Business Model Innovation in a Circular Economy. Master’s Thesis, Lahti University of Technology, Lappeenranta, Finland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nußholz, J.L.K. A circular business model mapping tool for creating value from prolonged product lifetime and closed material loops. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepin, M.; Tremblay, M.; Audebrand, M. Responsible Business Model Canvas. Available online: https://chaires.fsa.ulaval.ca/espritentrepreneuriat/en/our-tools/responsible-business-model-canvas/ (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Gjøsæter, Å.S.; Kyvik, Ø.; Nesse, J.G.; Årethun, T. Business models as framework for sustainable value-creation: Strategic and operative leadership challenges. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 15, 50–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.; Carter, C. The creative business model canvas. Soc. Enterp. J. 2020, 16, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egusquiza, A.; Arana-Bollar, M.; Sopelana, A.; Babí Almenar, J. Conceptual and Operational Integration of Governance, Financing, and Business Models for Urban Nature-Based Solutions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stål, H.I.; Corvellec, H. A decoupling perspective on circular business model implementation: Illustrations from Swedish apparel. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, R.; Barros, M.V.; Donner, M.; Brito, P.; Halog, A.; De Francisco, A.C. How to advance regional circular bioeconomy systems? Identifying barriers, challenges, drivers, and opportunities. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 2022, 32, 248–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Carroux, S.; Joyce, A.; Massa, L.; Breuer, H. The sustainable business model pattern taxonomy—45 patterns to support sustainability-oriented business model innovation. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 2018, 15, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ellen MacArthur Foundation. The Butterfly Diagram: Visualising the Circular Economy. Available online: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy-diagram (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Richardson, J.E. The business model: An integrative framework for strategy execution. Strateg. Chang. 2008, 17, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, Y.A.; Kannan, D.; Govindan, K.; Hasibuan, Z.A. Circular economy e-business model portfolio development for e-business applications: Impacts on ESG and sustainability performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 415, 137528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Konietzko, J.; Bocken, N. How do companies measure and forecast environmental impacts when experimenting with circular business models? Sustain. Prod. Consump. 2022, 29, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamidullaeva, L.; Shmeleva, N.; Tolstykh, T.; Shmatko, A. An assessment approach to circular business models within an industrial ecosystem for sustainable territorial development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Marfil, J.-A.; Arimany-Serrat, N.; Hitchen, E.L.; Viladecans-Riera, C. Recycling technology innovation as a source of competitive advantage: The sustainable and circular business model of a bicentennial company. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smitskikh, K.V.; Titova, N.Y.; Shumik, E.G. The model of social entrepreneurship dynamic development in circular economy. Univ. Y Soc. 2020, 12, 248–253. [Google Scholar]

- Staicu, D. Characteristics of textile and clothing sector social entrepreneurs in the transition to the circular economy. Ind. Textila 2021, 72, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłoński, A.; Jabłoński, M. Business Models in Water Supply Companies—Key Implications of Trust. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staicu, D.; Pop, O. Mapping the interactions between the stakeholders of the circular economy ecosystem applied to the textile and apparel sector in Romania. Manag. Mark. 2018, 13, 1190–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Chaarani, H.; Raimi, L. Determinant factors of successful social entrepreneurship in the emerging circular economy of Lebanon: Exploring the moderating role of NGOs. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2022, 14, 874–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real, M.; Lizarralde, I.; Tyl, B. Exploring Local Business Model Development for Regional Circular Textile Transition in France. Fash. Pract. 2020, 12, 6–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, F. When the business is circular and social: A dynamic grounded analysis in the clothing recycle. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 135216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chineme, A.; Assefa, G.; Herremans, I.M.; Wylant, B.; Shumo, M. African Indigenous Female Entrepreneurs (IFÉs): A Closed-Looped Social Circular Economy Waste Management Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, R.; Yarnold, J.; Pushpamali, N.N.C. Circular economy 4 business: A program and framework for small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs) with three case studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 412, 137114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piller, L.W. Designing for circularity: Sustainable pathways for Australian fashion small to medium enterprises. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2023, 27, 287–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, G. Business Model Innovation to Create and Capture Resource Value in Future Circular Material Chains. Resources 2014, 3, 248–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, O.; Ritala, P.; Keränen, J. Digital Platforms for the Circular Economy: Exploring Meta-Organizational Orchestration Mechanisms. Organ. Environ. 2022, 36, 10860266221130717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohal, A.; De Vass, T. Australian SME’s experience in transitioning to circular economy. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perey, R.; Benn, S.; Agarwal, R.; Edwards, M. The place of waste: Changing business value for the circular economy. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2018, 27, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, K. Design-led innovation and Circular Economy practices in regional Queensland. Local Econ. 2019, 34, 382–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daljit Singh, J.K.; Molinari, G.; Bui, J.; Soltani, B.; Rajarathnam, G.P.; Abbas, A. Life Cycle Assessment of Disposed and Recycled End-of-Life Photovoltaic Panels in Australia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasabapathy, S.; Alashwal, A.; Perera, S. Exploring the barriers for implementing waste trading practices in the construction industry in Australia. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2021, 11, 559–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Hong Kong, China, 2009; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Nygaard, S.; Kokholm, A.R.; Huulgaard, R.D. Incorporating the sustainable development goals in small- to medium-sized enterprises. J. Urban Ecol. 2022, 8, juac022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, E.; de la Cuesta-González, M.; Boronat-Navarro, M. How Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Can Uptake the Sustainable Development Goals through a Cluster Management Organization: A Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, I.; Khan, M.N.A.; Hasan, R.; Ashfaq, M. Corporate board for innovative managerial control: Implications of corporate governance deviance perspective. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2021, 21, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, I.; Tahir, S.H.; Batool, Z. Beyond diversity: Why the inclusion is imperative for boards to promote sustainability among agile non-profit organisations? Int. J. Agil. Syst. Manag. 2021, 14, 254–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, M.; Hoogenstrijd, T.; Kirchherr, J. Motivations and identities of “grassroots” circular entrepreneurs: An initial exploration. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2022, 32, 1122–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The 17 Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Scheepens, A.E.; Vogtlander, J.G.; Brezet, J.C. Two life cycle assessment (LCA) based methods to analyse and design complex (regional) circular economy systems. Case: Making water tourism more sustainable. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Kumar, A.; Anwar, S.; Gupta, S.N. Technology oriented value propositions for Bluetown Case. In Proceedings of the 2019 22nd International Symposium on Wireless Personal Multimedia Communications (WPMC), Lisbon, Portugal, 24–27 November 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

| Name of the Canvas | Reference | Country of Origin of the Canvas According to the First Author | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Business model canvas (BMC) | Osterwalder and Pigneur [3] | Switzerland | The “Business Model Canvas” is an adaptable framework for conceptualizing, completing, and evaluating business models. |

| Lean canvas | Maurya [39] | Nigeria | The lean canvas is the ideal one-page format for generating potential business models; the blocks direct you through logical stages beginning with your customers’ problems and ending with your competitive advantage. |

| Value proposition canvas | Osterwalder and Pigneur [3] | Switzerland | The framework was developed to ensure that the product and market are compatible. It is an instrument for modeling the relationship between consumer segments and value propositions, two components of Osterwalder’s business model canvas. |

| Circular business framework (CBF) | Lauten-Weiss and Ramesohl [40] | Germany | It follows design research methodology (DRM) and structures business ideas. |

| ECOCANVAS | Daou, Mallat, Chammas, Cerantola, Kayed and Saliba [20] | Lebanon | Tool that highlights unique circular value propositions based on a lifecycle perspective. |

| Circular collaboration canvas | Brown, Baldassarre, Konietzko, Bocken and Balkenende [32] | The Netherlands | Focuses on design thinking approach to stimulate collaborative ideation of circular propositions. |

| Circular by design canvas | Ballie and Woods [41] | Scotland | The instrument is intended to assist SMEs in adopting closed-loop systems and identifying the most suitable sustainable design strategies for their business. |

| reDesign canvas | Kozlowski, Searcy and Bardecki [38] | Canada | The instrument is intended to assist fashion designers in establishing sustainable businesses. |

| Flourishing business canvas | Hoveskog, Halila, Mattsson, Upward and Karlsson [28] | Canada | A tool for collaborative visual business modeling integrated with the service-learning pedagogic approach. |

| Strongly sustainable business model canvas | Kurucz, Colbert, Luedeke-Freund, Upward and Willard [25] | Canada | Based on the Framework for Strategic Sustainable Development (FSSD) advancing strategic sustainable organization management. |

| Demand response business model canvas | Hamwi, Lizarralde and Legardeur [16] | France | Cost-efficient and sustainable power system. The framework helps to understand, integrate, and develop flexible electricity products. |

| Social enterprise (SE) to sustainability canvas | Rahdari, Sepasi and Moradi [30] | Iran | It is predominantly of interest to socio-economic policymakers and scholars of social entrepreneurship, but it also benefits social and commercial enterprises integrating sustainable development goals. |

| Sustainable circular business model innovation framework | Maria and Katri [42] | Finland | Recognizing trends and drivers at the ecosystem level, comprehending the value to partners and constituents within a business, and evaluating the impact of sustainability and circularity led to the development of the framework. |

| Sustainable business model canvas | Schuit et al. [43] | the Netherlands | Experimentation practices and business model experimentation among startups. |

| Adapted sustainable business model canvas | Bocken, Schuit and Kraaijenhagen [29] | Sweden | It focused on “circular economy” as a driver for sustainability. |

| Sustainable business model framework | Bocken [26] | The Netherlands | This framework aims to assist businesses in transforming their business models for the creation of shared value, resulting in sustainable business models. |

| Conceptual framework for business case analysis | Donner et al. [44] | France | Provided an understanding of the CBMs valorizing olive oil waste and by-products. |

| Sustainable business model canvas for offshore platforms | Basile, Capobianco and Vona [27] | Italy | The instrument provides a holistic perspective of the various multiuse management options and their social and environmental impacts. |

| Integrated SBM-IP canvas. | Hernández-Chea, Vimalnath, Bocken, Tietze and Eppinger [33] | Sweden | It focuses on innovations in sustainable business models (SBM) as a means of systemically transforming businesses towards sustainability. |

| Circular and Sustainable business model canvas | Mendoza et al. [45] | United Kingdom | It emphasizes an action-driven, step-by-step approach to developing a business case and putting circular economy thinking into practice. |

| Back casting and eco-design for the circular economy (BECE) framework | Mendoza et al. [46] | United Kingdom | Focuses on CE thinking and requirements from organizational context. |

| The circular business model canvas | Okorie, Charnley, Russell, Tiwari and Moreno [22] | United Kingdom | CBM adoption in high value manufacturing (HVM) sector focusing on resource flows, supply chains, and business models and value creation. |

| Triple bottom line business model canvas (TLBMC) | Joyce and Paquin [18] | Canada | The instrument facilitates the development and communication of a more comprehensive and unified view of a business model. |

| Circular building components generator” (CBC-generator) | van Stijn and Gruis [47] | The Netherlands | A design tool that aids in the creation of circular structural components. |

| Framework of the circular business model canvas | Lewandowski [19] | Poland | Designing a CBM and conceptualization of an extended framework for the CBM canvas. |

| The value hill | Achterberg, Hinfelaar, and Bocken [34] | The Netherlands | It aids in the development of future business strategies for the circular economy. |

| Business model canvas | The Ellen MacArthur Foundation [48] | United Kingdom | Modifications made in terms of specific questions placed in the building blocks of the traditional BMC. |

| C3 Business model canvas | Hofmann, Marwede, Nissen and Lang [17] | Germany | To implement the concept of circularity in enterprise architecture at the business level, integrated strategies comprised of factors of sufficiency, consistency, and efficiency are required. |

| Business cycle canvas | Mentink [49] | The Netherlands | It outlines a process of 18 typical obstacles—or challenges. |

| Circular business model framework | Nußholz [23] | Sweden | Highlighted the necessity of resource efficiency strategy with circular strategies with an emphasis on product lifecycle management. |

| Circular business model mapping tool | Nußholz [50] | Sweden | The tool is more focused on reverse supply chain (e.g., product recovery). |

| The responsible business model canvas (RBMC) | Pepin et al. [51] | Canada | It involves in-depth consideration of the requirements of sustainable development. |

| Three-dimensional canvas of the sustainable business model with risk components | Wit and Pylak [24] | Poland | It illustrated reverse logistics with a specific focus on stakeholders’ perspective. |

| The smart city business model framework | Giourka, Sanders, Angelakoglou, Pramangioulis, Nikolopoulos, Rakopoulos, Tryferidis and Tzovaras [14] | Greece | The framework facilitates the development and communication of a more integrative and integrated business model for smart cities. |

| Business model canvas for sustainability | Cardeal, Höse, Ribeiro and Götze [15] | Portugal | The tool provides a procedure and evaluation model that facilitates the design and evaluation of sustainable business models. |

| The business model canvas (adapted) | Gjøsæter et al. [52] | Norway | Corporate sustainability management and development. It suggests adjustments to a company’s resources and capabilities, as well as its strategic and industrial environment and operations. |

| Creative business model canvas (CBMC) | Carter and Carter [53] | Australia | It demonstrated the value of business planning for a visual artist from the perspective of sustainable business models by incorporating organizational motivations and financial objectives. |

| Governance, finance, and commercial models (NBS)-based canvas | Egusquiza et al. [54] | Spain | It can evaluate business model components with a focus on urban nature-based solutions (NBS). |

| Circular economy business model canvas | Pollard, Osmani, Grubnic, Díaz, Grobe, Kaba, Ünlüer and Panchal [21] | United Kingdom | It supports electrical and electronic (E&E) manufacturers in developing circular economy (CE) actions that lead to value proposition, creation, and capture opportunities. |

| Circular business model tool | Geissdoerfer, Pieroni, Pigosso and Soufani [2] | United Kingdom | CBM related aspects are directly incorporated in the CBM strategies inside the canvas. |

| Name of the Canvas | Reference | Sustainability-Related Aspects | Circularity Related Aspects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circular business framework (CBF) | Lauten-Weiss and Ramesohl [40] | Environment | Three CE principles, circular design, CE analytics. |

| ECOCANVAS | Daou, Mallat, Chammas, Cerantola, Kayed and Saliba [20] | Environmental and social foresight and impact | CBM and innovation, circular value chain, unique circular value proposition. |

| Circular collaboration canvas | Brown, Baldassarre, Konietzko, Bocken and Balkenende [32] | - | Partner identification for circular value proposition design. |

| Circular by design canvas | Ballie and Woods [41] | - | Circular design, product/process lifecycle-specific. |

| reDesign canvas | Kozlowski, Searcy and Bardecki [38] | Supply chain and business model perspectives | Circular strategies (slowing the loop, closing the resource loops, and narrowing resource loop), circular cycles. |

| Flourishing business canvas | Hoveskog, Halila, Mattsson, Upward and Karlsson [28] | In the environment layer in the canvas, the canvas has two main components: biophysical stocks and ecosystem service, while ecosystem actors, and needs are overlayed in the three layers concurrently. | - |

| Strongly sustainable business model canvas’ | Kurucz, Colbert, Luedeke-Freund, Upward and Willard [25] | Triple bottom line contexts included | - |

| Social enterprise (SE) to sustainability canvas | Rahdari, Sepasi and Moradi [30] | Sustainable development, sustainable and responsible products/service, operation/processes, attitudes, and sustainable responsible business model | - |

| Sustainable circular business model innovation framework | Maria and Katri [42] | Sustainability requirements, sustainability benefits | Circularity evaluation. |

| Sustainable business model canvas | Schuit, Baldassarre and Bocken [43] | Sustainable business model (SBM) | - |

| Adapted sustainable business model canvas | Bocken, Schuit and Kraaijenhagen [29] | Value as the main essence that separates the conventional business model and SBM | - |

| Conceptual framework for business case analysis | Donner, Radic, Erraach and El Hadad-Gauthier [44] | - | CE principles, and business models. |

| Sustainable business model canvas for offshore platforms | Basile, Capobianco and Vona [27] | SBM, eco-social aspects of business model | - |

| Circular and sustainable business model canvas | Mendoza, Gallego-Schmid and Azapagic [45] | Value proposition building block integrating economic, social and environmental sustainability | Integration of circular campus. |

| Back casting and eco-design for the circular economy (BECE) framework | Mendoza, Sharmina, Gallego-Schmid, Heyes and Azapagic [46] | Environmental impacts, eco-design indicators, lifecycle assessment | CE vision, strategies, and scenarios. |

| The circular business model canvas | Okorie, Charnley, Russell, Tiwari and Moreno [22] | Economic value, social responsibility, environmental value | - |

| Triple bottom line business model canvas (TLBMC) | Joyce and Paquin [18] | Representing triple bottom line for various building blocks in economic, social and environment dimensions. | - |

| Circular building components generator” (CBC-generator) | Van Stijn and Gruis [47] | Greener products | Circular design, circular building component (CBC)-generator. |

| Framework of the circular business model canvas | Lewandowski [19] | PEST factors including social and environmental aspects of business model | Take-back systems. |

| The value hill | Achterberg, Hinfelaar, and Bocken [34] | Five R-strategies: repair/maintain, reuse/redistribute, refurbish, remanufacture, recycle. | Yes. Covered mainly CE principle: P2 with specific focus on circular materials as part of the P1. |

| Business model canvas | The Ellen MacArthur Foundation [48] | - | In all aspects, specifically, in key partnerships, key resources. |

| C3 business model canvas | Hofmann, Marwede, Nissen and Lang [17] | Biosphere as an environmental/ecological aspect with ecological cost as part of cost structure. Stakeholder as social dimension, and circular business model as economic dimension. Social component was highlighted in the VP as social affiliation. | Mostly focused on circular business network-oriented narrative. Circular added value-based business model design. |

| Business cycle canvas | Mentink [49] | - | CBMI, circular supply chain. |

| Circular business model framework | Nußholz [23] | Resource efficiency strategies | Business model canvas that incorporates lifecycle value management systematically: the nine building blocks of the business model canvas are offset to three circular lifecycle points (resource recovery, prolong lifespan, and end-of-life). |

| Circular business model mapping tool | Nußholz [50] | Value dimensions from SBM framework of Schuit, Baldassarre and Bocken [43]. | Product lifecycle perspectives and resource strategies. |

| The responsible business model canvas (RBMC) | Pepin, Tremblay and Audebrand [51] | Impacts areas are focused on triple bottom lines | - |

| 3D canvas of the sustainable business model with risk components | Wit and Pylak [24] | Economic, social, and environmental responsibility | - |

| The smart city business model framework | Giourka, Sanders, Angelakoglou, Pramangioulis, Nikolopoulos, Rakopoulos, Tryferidis and Tzovaras [14] | Sustainable value creation | - |

| Business model canvas for sustainability | Cardeal, Höse, Ribeiro and Götze [15] | Sustainability assessment, lifecycle costing, lifecycle assessment | - |

| The business model canvas (adapted) | Gjøsæter, Kyvik, Nesse and Årethun [52] | Corporate sustainability management | - |

| Creative business model canvas (CBMC) | Carter and Carter [53] | Focused on social enterprise organizations | - |

| Governance, finance, and commercial models (NBS)-based canvas | Egusquiza, Arana-Bollar, Sopelana and Babí Almenar [54] | Integration of sustainable business model (SBM) approach and market-shaping techniques. | - |

| Circular economy business model canvas | Pollard, Osmani, Grubnic, Díaz, Grobe, Kaba, Ünlüer and Panchal [21] | Corporate social responsibility, eco-design | Logistics and distribution, skills, and training. |

| Circular business model tool | Geissdoerfer, Pieroni, Pigosso and Soufani [2] | - | CBM strategies such as cycling, extending, intensifying, and dematerializing. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Islam, M.T.; Iyer-Raniga, U. Circular Business Model Value Dimension Canvas: Tool Redesign for Innovation and Validation through an Australian Case Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511553

Islam MT, Iyer-Raniga U. Circular Business Model Value Dimension Canvas: Tool Redesign for Innovation and Validation through an Australian Case Study. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511553

Chicago/Turabian StyleIslam, Md Tasbirul, and Usha Iyer-Raniga. 2023. "Circular Business Model Value Dimension Canvas: Tool Redesign for Innovation and Validation through an Australian Case Study" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511553

APA StyleIslam, M. T., & Iyer-Raniga, U. (2023). Circular Business Model Value Dimension Canvas: Tool Redesign for Innovation and Validation through an Australian Case Study. Sustainability, 15(15), 11553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511553