Abstract

One of the most important issues for higher education institutions is achieving financial viability and sustainability by expanding revenue sources, as the costs associated with ensuring the operation of higher education institutions is increasing. Therefore, raising funds through donations for universities means new challenges. Within the framework of this study, the authors have drawn attention to attracting funds to universities from patrons of universities and companies, providing a detailed analysis of trends in this field. The purpose of this study was to analyze the general trends in fundraising among university patrons and businessmen, and to identify possible solutions that could help in attracting donations to universities and promote their sustainability in the future. The research methodology applied in this research included analysis of the literature, conducting surveys, and analysis using statistical methods such as the correlation method, chi-squared test, and ANOVA. This study provides an insight into the situation in Latvia regarding the trends of patrons and entrepreneurs donating to universities. The results of this study show that philanthropic organizations should work on building a feedback relationship with patrons to promote as much fundraising as possible.

1. Introduction

The growing importance of philanthropy in higher education has been studied and confirmed by researchers around the world. This confirms that universities must invest in the formulation of their philanthropic goals and objectives [1].

In addition to state funding, universities increasingly actively seek donations for various scholarships and research projects from private patrons and entrepreneurs. This indicates that the costs of universities exceed revenues [2]. Currently, universities face unprecedented opportunities in terms of receiving funding from the state and various European grants; however, to attract this funding, additional funding must be found from patrons—both private individuals and companies—to be able to compete in the world market and prove their competitiveness at a national level. To achieve this, it is necessary to reduce costs while increasing productivity, and find alternative sources of income [3]. This problematic situation means that universities should more intensively look for various sources of funding, including donations from patrons for university projects and scholarships. Since state funding for universities is limited [4] and it can also be driven by political decisions, universities must find new solutions. Governments in many countries are reducing funding for university research projects. As state funding decreases, excellent research results are still expected from universities. Although tuition fees are gradually being increased, the quality of studies should also justify investments in higher education budgets [5]. New funding sources should be sought and one of these could be donations. Donations and public funding for research are equally important; it would be dangerous for research to depend on only one source of funding [6].

Achieving successful financial sustainability by expanding revenue sources is one of the most important issues facing universities today. The costs associated with ensuring the operation of universities is increasing. Traditional sources of income are student tuition fees and government support, along with various grants for research. That is why raising funds through donations for universities presents new challenges. In order to avoid excessive reliance on donations, universities create additional revenue streams from various other sources, such as continuing education, guaranteeing loans, providing study abroad, opening local and international branches, distance education, support services (such as technology transfer), and partnerships or alliances with other organizations. This type of activity, which was previously considered secondary in the context of universities, has now become an integral part of long-term and responsible financial strategic planning [7].

For universities to compete fully, they must not stop at what they have achieved. This is why it is crucial to expand the involvement of the private sector in university development. It is a philanthropic task [8] to increase the volume and number of private and business donations for different university projects. Worldwide, donation to universities is seen as a very important prerequisite for the full development of higher education institutions [1,9]. At the same time, researchers have discussed factors affecting the behavior of patrons [10], a successful philanthropy strategy [1], and the institutional development of universities [11]. The need to multiply philanthropic methods and increase the key role of philanthropy has been recognized worldwide [12]. Currently, university funding mainly comprises state grants, study fees, and research grants from various European Union support programs. Donating to universities is an essential part of financial support, increasing the external revenue stream [13], and contributing to the university’s development prospects.

The purpose of this study was to analyze the general trends characterizing the attraction of funding among patrons of higher education institutions and entrepreneurs, and to identify possible solutions that could contribute to the attraction of donations to higher education institutions and promote the sustainability of higher education institutions in the future.

Research hypothesis—donations from companies have a much greater advantage than individual donations.

The research will enable philanthropic organizations to improve their fundraising tactics. The data included in the study and the analysis thereof will enable philanthropic organizations to improve their daily work with donors—both current and prospective supporters.

Implications of the study on the sustainability issue. Sustainability issues have been among the most pressing research issues on the agenda of university researchers whose financial support is sought by philanthropic organizations from patrons.

The research is significant precisely because of the underfunding of higher education. This study presents an opportunity for philanthropic organizations to improve their work skills, as the result of a successful fundraising campaign depends on careful data analysis. The more patrons that support university researchers, the more knowledge-based research will be created to improve the environment, and thus the quality of life for society as a whole.

A possible weakness of this study is the impact of the pandemic and war on fundraising. However, the data indicate that fundraising trends are unaffected by these two aspects.

In the following chapters of the article, an analysis will be made of the trends in attracting donations, the profiles of donors and the amounts of donations, as well as the research of the contributions by various authors pertaining to the topics raised in the article.

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. Historical Aspects of Patronage and Experience of Other Countries

Within the framework of this subsection, the historical aspects of the emergence of patronage will be examined in order to better understand the history of patronage and the trends that have developed over the years.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the United States experienced a major shift in public support for university funding. The support dropped radically; therefore, universities had to pay more attention to attracting funds from patrons, including university graduates. Consequently, the number of philanthropic researchers increased, and they started active research to help universities and their philanthropic organizations to be more successful in raising funds. Therefore, the intensity of research on fundraising increased from the 1970s and continued until the 2010s, when there was a decline in research, because the most important aspect of fundraising had been studied in detail. Although the concept of fundraising is well known in the United States, in Europe it is still less traditional to focus on giving at the university level, and this area remains under-researched.

Latvia regained its independence in 1990; before that, any philanthropic activities were eradicated during the 50-year Soviet occupation period. Nowadays, attracting more and more funds helps to improve the country’s economic situation and allows support to be given to various projects, from environmental protection and sports, to culture and education.

The growing importance of philanthropy in higher education has been studied and confirmed by researchers around the world. This confirms that universities must invest in the formulation of their philanthropic goals and objectives [1]. Below, we will look at the trends and experiences of donations in different countries of the world.

Cultivating the traditions of philanthropy contributes to the formation of a civilized society. Philanthropy is first associated with the ideas of care and compassion. The ability to empathize and care for strangers is a sign of societal and individual maturity [14]. Universities are increasingly turning to fundraising to meet budget requirements and ensure their future sustainability. Several studies have analyzed the growing interest of universities in philanthropy, volunteer work, and non-governmental organizations, illustrating the industry’s efforts to redefine its public presence by influencing universities and researchers. The research examines various approaches that can be used to evaluate the changing place of universities in public life, the processes of change in universities, and the effectiveness of strategies used in the industry. The most effective fundraising strategies are carefully planned and implemented to achieve the set goals. The feedback is not only via the number and volume of donations made, but also the satisfaction of donors, receiving, for example, appreciation from the foundations for the donation made. Research has highlighted that philanthropy, voluntary work, and non-governmental organizations should be popularized among young researchers to ensure better organization of donation campaigns [15,16].

The types of donations in general can be vastly different. A study carried out in the United States listed a few—these can be blankets for the homeless, the purchase of various products for the provision of charity events, up to multi-million-dollar donations and billion-dollar campaigns to ensure the quality of American higher education. Civic responsibility for improving the quality of life in one’s community has been part of the American ethos since the founding of the colonial colleges. Peter Dobkin Hall in 1992 noted: “no single force has contributed more to the development of the modern university in America than the contributions of individuals and foundations” [8].

To ensure development and competitiveness in the long term, universities need to diversify their sources of external funding and the ways of obtaining it. Universities need to develop diverse networks of forms of external funding through a more strategic approach [17].

According to Perez-Esparells and Torre (2012), university fundraising could be defined as the pursuit of philanthropic private funding by seeking private individuals or organizations willing to share in the organization’s goals and results through financial contributions. It is an additional income stream to support a specific university purpose or institutional development (specified or unspecified), consisting of gifts, grants, and cash payments, returned as employee contributions and insurance payments made by donors. Volunteering should be provided to the university and its various institutions (foundations, colleges, schools, departments, institutes, alumni organizations, etc.) by alumni, foundations, corporations, or other interested organizations sharing in the values, goals, and performance of universities [18].

Institutional development of universities in the United States is a highly professional field. This is less common in universities in Europe and almost unknown in Mediterranean countries such as Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece, etc. If university fundraising is about institutional development, there needs to be a general and long-term commitment from the donor to the institution’s financial and physical growth and, hence, a wider understanding of the institution and its mission. Thus, institutional development will also contribute to the further development of voluntary giving as feedback [18].

For the higher education sector to retain the characteristics of a European welfare economy, and since public funding needs to be complemented by private funding to cover the costs of excellence, university fundraising is essential to provide the necessary additional funds. In this regard, some European countries have established schemes with similar objectives to improve excellence. Most of the European universities try to leverage funds from philanthropic sources (foundations, trusts, charities, non-profit organizations, corporate and individual donors, alumni), but with mixed results. Disappointing results are often due to a lack of a strategic approach (fundraising is not considered as part of the universities’ funding strategy) and a lack of a professional unit of fundraising or a Development office, mainly in the Mediterranean countries (France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece, etc.). Moreover, peer learning is difficult given the lack of reliable data on university fundraising in Europe, as well as the huge diversity of legal, institutional, historical, cultural, and economic contexts in European countries [18].

Economists have studied charitable motives theoretically, empirically, and experimentally, yet there is a void in the literature to understand charitable behavior in cases when the potential donor is also a client of the organization [19].

Mahone (2021) emphasized that it is now possible to successfully strategically collaborate and support alumni associations as social media and virtual opportunities are more accessible than ever before. Our institutions must embrace emerging trends and tax-advantaged opportunities while leveraging events in a way that promotes philanthropy rather than serving as the dominant strategy each fiscal year. University presidents and board members rely heavily on philanthropy as a source of outside revenue to support the operations and expansion of their institutions. As tuition revenue models exceed what our students can afford, the demand for growth will become more important in the future. Institutional leadership must have the best understanding of what philanthropy is and is not, and how their leadership and vision can support the culture of philanthropy necessary to develop competitive access to higher education [20].

Sziegat and Hong (2020) have conducted research on philanthropic fundraising policies and practices in Chinese universities, focusing on university foundations. The authors have drawn attention to the theoretical dimensions of philanthropic fundraising in higher education from a global perspective and university philanthropic fundraising models, as well as their application in Chinese universities. The study pointed to the important role of university foundations in generating philanthropic revenue in Chinese universities [21].

Rohayati, Najdi, and Williamson (2016) highlighted that while some institutions have been successful in attracting philanthropic support, many still struggle to succeed. The authors concluded that determining the basic principles of fundraising and creating an appropriate internal and external environment of the university are important organizational features for the successful philanthropic fundraising of state higher education institutions. A shift in institutional philanthropic culture is necessary to foster sustainable growth in philanthropy in public higher education. The authors believe that demographic and socio-economic characteristics also influence donors’ giving. It is important to note that different cultures and peoples have their own philanthropic traditions that form the basis of charity in society, and these should be respected and used. In a heterogeneous society, race, religion, custom, and tradition played a major role in influencing individual giving behavior in Malaysia and formed a fundamental platform that governed the fundraising system of successful institutional fundraising, compared to a more homogenous context such as Australia [22].

After analyzing various trends in attracting funds from other countries, it can be concluded that there are sufficient different studies and data analysis to be able to fully improve the attracting of funds, taking into account the experience of other countries.

2.2. Profile of Patrons and Potential Patrons, and Their Motivation

Within the framework of this subsection, the profile of patrons and potential patrons, as well as their motivation to donate, will be examined. The motivation of graduates to donate depends not only on the quality of the study environment, relationships with the administration, but also on the particular student’s own achievements in terms of their studies, quality of life, and wealth. The authors Baade and Sundbergs (1996) examined the correlation between the quality of the study environment and the quality of life of students, as well as the possible connections between the university’s administrative expenses for ensuring the quality of the study environment and donations received from graduates, their volume, and number. The authors concluded that quality variables had a positive effect on the average size and number of alumni donations. The quality of student life is also related to the amount and number of donations. The researchers concluded that the university’s development ambitions are an important factor for alumni to show their faith in the university’s development plans with their donation [23].

Referring to a study by Dvorak and Toubman (2012), it was found that women donate more often than men. This indicates that it is women who form long-term relationships more often, in this case, by donating small amounts, but more frequently. Men, on the other hand, who aspire more for recognition and attention, donate less often, but donate significantly larger amounts when they do donate. Women donate not only smaller amounts, but also to several causes or charities. Fundraising organizations should consider these factors when creating fundraising strategies, for example, these research findings indicate that women are better off making annual donations to a specific cause. However, men should preferably be invited to donate to a “special campaign” that would make their donation more unique and meaningful [24].

An important role in fundraising is played by the fundraising team, whose work is dedicated exclusively to fundraising. It is most appropriate to create one when circumstances compel the organization to raise funds. The culture of philanthropy must be developed thoughtfully and gradually, involving an increasing number of full-time employees. The relationship-building process is particularly important in the fundraising process, so that both potential and existing patrons are well informed about current projects and needs. The actual and potential patrons should propose projects that surpass the existing achievements. That is why fundraising teams should organize various events for potential and current patrons. First of all, ambitious goals should be set, and in order to realize them, three basic principles in building relationships should be observed:

- The patron is always the first, most important person.

- Work in such a way that for every dollar spent on raising funds, including staff salaries, as well as administrative and representation costs, at least two dollars must be raised.

- Never forget to thank sponsors and volunteers. They must constantly feel how important they are to the CEO personally [8,25].

Seifert, Morris, and Bartkus (2003) have been increasingly analyzing the correlations of financial data related to corporate donors. Their studies put forward two hypotheses. The first is: the amount of the donations depends on the enterprise’s potential free financial resources. It has been concluded that companies whose development strategies also provide guidance on the allocation of donations are pursuing a much more prudent financial flow policy. Researchers call this approach “strategic philanthropy”. The second hypothesis claims: There is a positive correlation between corporate philanthropy and the company’s financial performance. Research concluded that it is business executives who are more interested in making donations, as this strengthens their social wellbeing image in society. Research has revealed that corporate shareholders see donations as a loss or a decline in dividend shares [26].

Bekkers (2002) conducted a study in which he surveyed 612 citizens of the Netherlands to find out the dynamics between donating to charity and donating voluntary work to various non-governmental organizations. The researcher found that those respondents who donated their time working as volunteers were also more active donors of money to various charitable organizations. Voluntary donors generally donated funds to the non-governmental organizations where they volunteered, although donors were also found to donate to a variety of other philanthropic organizations, such as health sector philanthropies, religious organizations, and various sports organizations. Therefore, they also donated to philanthropic organizations that were not part of their daily interests. However, the researcher observed that there was no causal relationship between the determining factors of volunteering and the motivation to donate—it was not found that volunteering would significantly affect the motivation to donate. The researcher concluded that volunteering was a complementary behavior caused by approximately the same social factors as donation [27].

On the other hand, Rolland (2019) [28] pointed out that private-individual donors have become more active, and these donations provide a relatively large part of the support for non-governmental organizations. Most consider psychographic criteria, such as beliefs, values, lifestyle, social status, opinions, and activities, as a basis for patron segmentation and selection of potential target audience—donors. Researchers suggest combining socio-demographic characteristics with behavioral aspects. This would create a more comprehensive vision, allowing people to look at effective criteria for the possible segmentation of patrons. After collecting data on Austrian philanthropists, the researchers established which individuals (by age, gender, and social class) donate certain amounts, how often, to which organizations, and in what ways. After reviewing the data and statistical results, the researchers put forward three basic conditions, according to which individuals are especially favorably inclined towards donation:

- If the goal of public good is related to an area of interest to the individual.

- If a person could benefit from the services of a public benefit organization.

- If the donation is easy to make and does not require too much effort [28].

Berman and Davidson (2003) pointed out that it is generally believed that individuals would donate more to charity if they were sure that the funds would not be “wasted”. This is a common answer in surveys about the motivation to donate to charity. The research analyzed legislation and financial indicators to explore the validity of this claim in the Australian context. A responsibility variable was developed, then linked to charitable giving. The researchers concluded that the relationship between the two is statistically weak and not stable [29].

Chen, Li, and MacKie-Mason (2005) conducted one of the first web-based online experiments in fundraising. On the public library’s online donation website, it was possible to donate in four different ways: volunteer work, a larger donation, a small donation, and a donation against a donation, when the amount donated automatically attracts an equal amount from another source—the so-called “matching donation”. The study confirmed that supporters were more likely to choose to make a small donation or donation against a donation, while larger donations were less common. The technology enabled the donation procedure to be shortened and simplified, and this was proven to be justified. If the online donation mechanism offered on the internet was simple and easy to follow, donors referred directly to the simplified opportunity to donate [30].

Houston (2006) concluded that public administration employees are more likely to volunteer their time and become blood donors than those employed in the private sector. Likewise, those employees who work in non-governmental organizations have a greater understanding of the importance of volunteer work. The researcher assumes that private-sector employees donate more money because they are profit-oriented on a daily basis [31].

Bekkers and Crutzens (2007) concluded that donors have less trust in those philanthropic organizations that spend more on administrative resources. A flashy visual presentation had a negative effect on the willingness to donate among the group and indicated less trust in philanthropic organizations. A finding that appeared to contradict this interpretation is that, among random donors, the flamboyant solicitation letter design elicited more negative attitudes in those who had previously donated larger amounts to the organization in question. Perhaps this result reflects a more critical attitude towards the philanthropic organization and its new approach of sending flashy letters suggesting high administrative costs. The researchers emphasized that previous studies confirmed that donors were deterred by the high administrative costs of philanthropic organizations’ fundraising campaigns [32].

However, Khodakarami, Petersen, and Venkatesan (2015) concluded that when donating for the first time, most donors support one initiative, and these decisions are largely influenced by the donor’s own motivation. In contrast, as the donor–NGO relationship develops over time, the marketing activities of the NGO have a more significant impact on the donor’s decision to support multiple initiatives. Finally, the researchers conducted a field study that confirmed the findings of the econometric analysis and provided causal evidence that NGO marketing activities can encourage donors to donate to multiple initiatives [33].

These conditions are offered as characteristics for the selection of specific segments of donors, allowing philanthropic organizations to attract funds more effectively, using easily obtainable socio-demographic data for this purpose. The researchers observed that older people most often support social services, health care, and emergency services through volunteer work. Older people tend to choose to support such services more often than younger people, anticipating that the services they volunteer for will soon be needed themselves. Therefore, they are more interested in supporting philanthropic organizations whose work is dedicated to these areas. Individuals who are less educated prefer to donate to health care and emergency care. It can be assumed that this group, like the elderly mentioned above, is more likely to benefit from these philanthropic organizations than people with a higher education who can afford insurance or fee-based services. The researchers concluded that the propensity to donate to a particular philanthropic organization increases with the opportunity to benefit from the services of that philanthropic organization. Younger people choose to donate blood, while older residents are more likely to donate organs. Intuitively, such decisions seem reasonable, since donating blood requires a good state of health to be able to withstand the physical and psychological stress associated with it. Older people, on the other hand, often want to “do something good” in life and could hope for a lasting memory by giving permission for organs to be used by people who need them to survive [28]. For younger people, death may seem too far away to start thinking about organ donation. A study showed that older people were more likely to donate when approached directly, such as in church, on the street, or through direct mail [34].

Various studies have emphasized several important conditions that contribute to the choice of donors to make a donation. They are as follows:

- Tax credits available to donors are an important factor in deciding in favor of a donation. The application of various tax discounts motivates donations to philanthropic organizations.

- Wealthy donors are motivated by exactly the same factors that motivate any donor at the time of giving. For wealthier donors, the decision to donate could be thought out over a longer period of time, especially if long-term donation is planned. The activity of wealthy donors can also be based on a sudden accident, such as a natural disaster.

- Trusting people to volunteer their time or funds to philanthropic organizations is more likely to be seen in countries that promote economic growth while supporting less successful people. Countries with greater mutual trust can boast better functioning governments, more open markets, and lower levels of corruption. Countries with more stable mutual trust have more successful philanthropic organizations [35,36,37].

In general, when analyzing the results collected by various researchers on donation trends and influencing factors, the main factors that impact the willingness to donate individually are education, gender, age, race, income, affiliation with a philanthropic organization, motivation to donate, and marital status. The researchers recognized that the main determining factor is the wealth of private individuals, and as an additional determining factor, the researchers pointed to an additional consideration—the wealth and well-being of the city where the private individuals live. The wealthier the city, the larger the private donations to various charitable causes [38,39,40].

The purpose of the current study was to explore general fundraising trends among senior philanthropic organizations and to analyze the data from a survey of high-ranking entrepreneurs on philanthropy trends in general. It is important to compare common trends to understand whether they differ from fundraising trends of philanthropic organizations.

3. Materials and Methods

General scientific research methods were used for the theoretical research:

- Monographically descriptive, historically descriptive, scientific induction, and deduction methods were used to provide a detailed view of the theoretical aspects of the topic (historical aspects of patronage, profile of patrons and potential patrons, and their motivation to donate), based on a wide review of the international scientific literature.

- The methods of analysis and synthesis to separate research topics into theoretical and practical aspects were combined into unified systems by studying their interrelationships.

- The graphic method was used in the general funding researching attractiveness trends among entrepreneurs.

The following methods of statistical research and econometrics were used to achieve the goal set in the study:

- ANOVA was used to analyze the legal entity donors, and to clarify the correlative relationship between the size of the donation, and the annual turnover and duration of existence of the legal entity donor, as well as the sector in which it operated, through correlation analysis. Analysis of variance or ANOVA is a statistical method used to determine whether the variances (i.e., distributions of values) of two or more samples are statistically significantly different [41].

- A chi-squared test was used to test for donation types and gender. The chi-squared test is a very practical test commonly used for determining whether any (perceived) frequencies have been diverted from the frequencies that might be expected under a certain hypothesis [42]. The use of economic statistics is mainly linked to addressing two sets of problems.

- The Pearson correlation method was used to analyze the data of the Lursoft database of the statistical data portal available in Latvia on the fundraising trends of all philanthropic organizations founded by state universities, in the period from 2011 to 2020, including donations of all philanthropic organizations from individuals and legal entities. The Pearson correlation coefficient is a measure of descriptive statistics. It is a linear measurement between two quantitative random variables that allows us to know the intensity and direction of their mutual relationship [43]. A correlation was calculated that indicated a statistically significant correlation between donations from individuals and legal entities.

The methodological basis of the research consisted of the work of foreign scientists, monographs, publications, and studies on the actualities of raising funds amongst patrons and entrepreneurs. In data processing, statistical analysis of the research data and presentation of the research results was carried out using the Microsoft Excel program and IBM SPSS Statistics 26 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) program. Sources of information used in this study: theoretical and methodological sources of the doctoral thesis, the base consisted of international scientific publications and studies, as there have been practically no applicable patronage studies conducted in Latvia. The main informative databases of consisted of Scopus, Web of Science, Emerald, ScienceDirect, EBSCOHost, Springer Link, Sustainability, etc.

For the discussion on general fundraising trends among entrepreneurs, the following data were used: The respondents were from the Business Network International (BNI) Morbergs organization, which at the time of the survey, had 50 members. This is a closed group, into which members can enter only according to certain criteria, if none of the existing members object to the potential member’s inclusion. The leaders of Latvia’s leading companies from various sectors have united in the BNI Morbergs group to mutually promote business growth with the help of recommendations. BNI members exchange qualitative and high-value recommendations, which are later converted into business deals. According to the statistical data of BNI Morbergs (Latvia), on average, one BNI member receives recommendations of more than €90,000 per year. Out of the 50 members of BNI Morbergs, 30 members completed the survey, comprising 60% of the total number of potential respondents. Of these respondents, 18 were male and 12 were female. Although the gender balance was equal, men were more active and responsive. The average age of respondents was 43.9 years. Explanation: The sum of the selected answers was obtained by adding up all the answers to the respective question marked by respondents. The percentage value of each answer was obtained by dividing the number of times the specific answer was selected by the total amount of submitted answers.

This survey addressed the following key issues:

- Do entrepreneurs make more money donations compared to donations received in kind, or as volunteers donating their time or providing services pro bono—offering a high-end counselling or expert advice for free?

- Are entrepreneurs more supportive of the following donation goals through their donations: charity, raising the social well-being of deprived and socially disadvantaged groups, promoting education, and supporting sport?

- Does the motivation to donate trigger a sense of satisfaction and joy, as well as the spirit of the race, taking an example from other grandstands?

- Are the most successful companies making donations ranging from €15,000 to €50,000?

- Does it matter to the descendants that the philanthropic organization ensures the transparency of its activities, is comfortable communicating with them, has a flawless reputation, has professional staff, does not overstate administrative expenditure, and informs the descendant regarding the use of the donation at least once a year?

The results of the study are provided in the next chapter.

4. Results

4.1. General Fundraising Trends among Entrepreneurs

To conduct a study on the experience of high-end business leaders providing a donation, 14 survey questions were prepared to analyze overall fundraising trends and compare them with data on fundraising trends in philanthropic organizations of state-founded universities.

As part of the study, answers were found to the above questions, as described in the following study discussion.

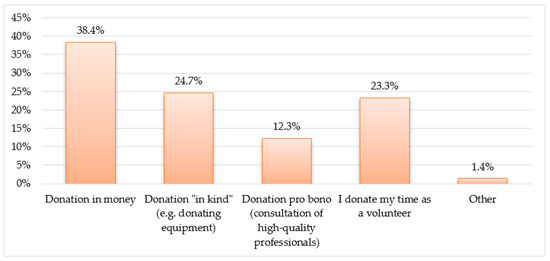

The study commenced with an analysis of the types of donations given. When asked about the types of donations provided, the majority of respondents indicated that they made monetary donations—38% of respondents. A similar assessment of respondents, with a difference of 2%, were donations in kind (e.g., gifts of equipment) (25%) and donations of time as volunteers (23%). The least-used form of donation was pro bono donations, i.e., providing high-ranking specialist advice for free. Furthermore, only 1% of respondents indicated another form of donation, which was a donation of individual shares (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Types of donations. Source: created by authors on the basis of survey results in 2022.

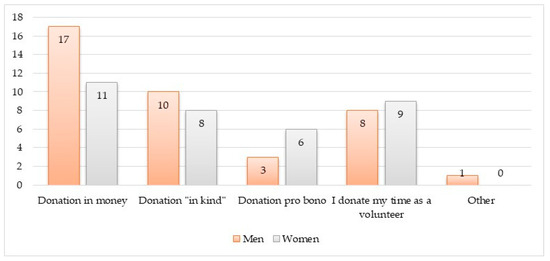

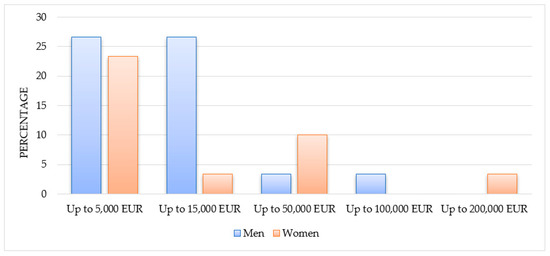

The analysis of the types of donations according to gender is depicted in Figure 2. Figure 2 shows that money donations are made more actively by men (17 respondents out of the total number of respondents), while women are more active with pro bono donations (6 respondents) and volunteers (9 respondents) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Types of donations and gender. Source: created by authors on the basis of survey results in 2022.

The chi-squared test was used below. Since χ2 = 3.24 < χ 20.05 = 9.49 (Df = 4, sign. = 0.000, n = 73), the zero hypothesis was confirmed and the questionnaire responses concerning the types of donations did not differ significantly between the respondents by gender.

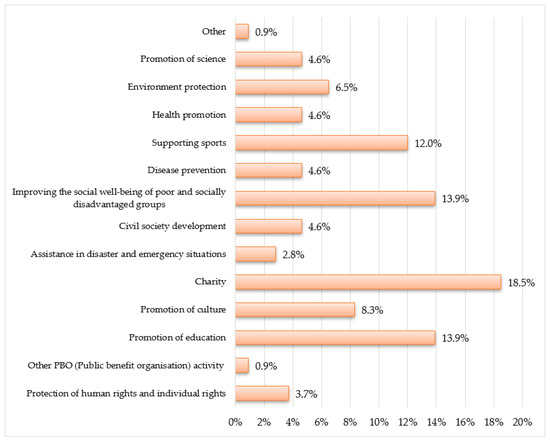

Figure 3 reflects the results of the survey dedicated to corporate donation targets. Public benefit status may be granted to organizations that have been given the opportunity to receive donations to support one of the 13 objectives listed in Figure 3. The highest proportion was achieved by “charity”, which was indicated by 19% of respondents; “raising social welfare of deprived and socially disadvantaged groups” and “promoting education” were in equal second place—14% of respondents. In third place was “supporting sports”—12% of respondents. In fourth place was “promoting culture”, which was indicated by 8% of respondents. Finally, in joint fifth place were several groups of donation targets—“protecting the environment”, “promoting science”, “promoting health”, “disease prevention”, and “developing civil society”—at 5% (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Goals of donations. Source: created by authors on the basis of survey results in 2022.

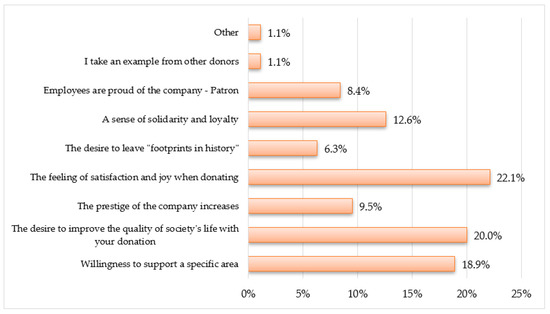

When asked about their motivation to donate, the leading response was “the feeling of satisfaction and joy when donating”, which was celebrated as motivation to donate by 22% of all respondents. The next-mentioned main motivator for donation was “the desire to improve the quality of society’s life with your donation”, which was noted by 20% of respondents. A further 18.9% of respondents noted “willingness to support a specific area”, while 12.6% of respondents donated because of “a sense of solidarity and loyalty”. Only 1.1% of respondents stated that they donated because of “I take an example from other donors”. It should be noted that the reason for this absence of the spirit of competition may be that philanthropic organizations are reluctant to use this fact in their donation campaigns (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Motivation of donations. Source: created by authors on the basis of survey results in 2022.

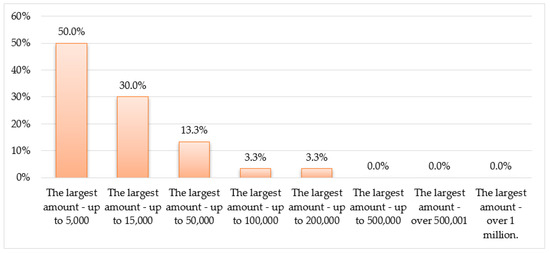

The survey results indicated that, when asked about the largest donated amount, half of respondents donated up to €5000, while 30% of respondents said they donated up to €15,000. A further 13% said they donated up to €50,000 (see Figure 5). Foreign studies indicate that donation amounts are generally higher [44]. It is accepted that this is a challenge for philanthropic organizations in their work with graduates, which unfortunately, is still at the incipient stage in terms of the University of Latvia environment.

Figure 5.

Donation amount. Source: created by authors on the basis of survey results in 2022.

The chi-squared test was used to determine the relationship between gender and the donation amount.

Since χ2 = 7.62 < χ 20.05 = 9.49 (Df = 4, sign. = 0.000, n = 30), the zero hypothesis was confirmed, and the questionnaire responses indicated that donation volumes did not differ significantly between respondents by gender.

An important aspect of philanthropy theories is the expression of gratitude to the donor for the donation. In terms of the question: “Does the gratitude of the philanthropic organizations for your donation match your expectations?”, 87% of all respondents responded positively. Only 13% responded negatively, but this number is quite large, indicating that philanthropic organizations should pay more attention to improving communication methods (see Figure 6). Most researchers have also emphasized the importance of this aspect [45].

Figure 6.

Donation amount by gender. Source: created by authors on the basis of survey results in 2022.

Respondents had the opportunity to make suggestions regarding improvements in the communication of philanthropic organizations with their patrons. Four responses were received:

- There is a lack of communication about the meaningful use of donated funds.

- More information should be available about the organization.

- Difficult to evaluate. This feedback may be different in each case. It has occasionally happened to me that they did not say “thank you”.

- Perhaps the report concerning the use of donated money.

The received answers indicate that it is important not only to say thank you, but to do it in such a way that the patron has the feeling of satisfaction and joy when donating. An important aspect, which is also indicated in the literature, is the application of the principle of transparency [46]. This means that reports on the use of the donation must be available. This is usually provided in by accountants who prepare this information for the management of philanthropic organizations. The management, in turn, contacts the patrons to pass this information on.

For example, the University of Latvia Foundation stipulates these conditions in donation agreements. For example, the donor’s right to include a clause with the following wording: “To check the use of the donation allocated to the philanthropic organization at any time, by requesting from the philanthropic organization the information that the patron needs to make sure that the allocated donation is used in accordance with the agreement. The philanthropic organization is obliged to provide the patron with the information requested by the patron to the philanthropic organization within 10 (ten) working days after the patron’s first request, at the latest, to check the use of the allocated donation”. Therefore, the philanthropic organization has agreed on specific steps for reporting.

When asked whether the respondents would like the philanthropic organization to express its pride concerning the received donation publicly, half agreed and half disagreed. On the other hand, it has been mentioned in the literature that it is important for patrons that a wider part of society learns about their donation, which could lead others to donate by their example [47]. This most clearly applied to university graduates. Setting a good example is an essential condition for additional donations [48].

When asked whether companies that donate had their own donation strategy policy, 70% of respondents said that there was no such policy. In the literature, however, it is mostly stated that companies have such donation strategy policies [49]. Admittedly, with the regaining of independence of Latvia, the companies in Latvia had an opportunity to start cooperating with philanthropic organizations, and this represented only a brief period wherein the local companies could take over the experience of their foreign partners in creating donation policies.

Respondents could also answer the question concerning whether they make donations every year. A total of 70% of respondents reported that they donate annually. It has also been confirmed by the literature that those who have started donating do so regularly [50].

When asked whether a specific purpose statement helps the company to make a positive decision to donate, 73% of respondents answered in the affirmative. This means that philanthropy practitioners should create lists of potential donation targets with descriptions. This has also been indicated by philanthropy researchers in the literature [51].

The survey asked whether the respondent agreed with the statement that women donated more frequently and in greater amounts than men, and 70% of respondents disagreed with this statement. A similar view exists in the literature [27].

The next question addressed corporate reputation, and 83% of respondents agreed with the statement that companies improve their corporate reputation by donating. The literature review expressed similar conclusions, revealing that companies care about their corporate reputation [45].

In Latvian society, there is an opinion that businessmen donate because they have tax credits. Consequently, the result was surprising, as 90% of the respondents answered that their company would donate even if there were no tax deduction. Another opinion was found in the literature, stating that the opportunity to receive tax deduction as a consequence of donation to a philanthropic organization is important for entrepreneurs [8,35,52,53,54].

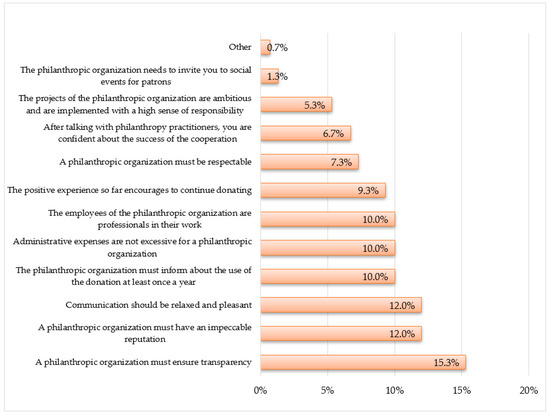

The survey also included a question inquiring as to what a philanthropic organization should do for a company to want to trust it and donate to it. Several answers were possible. The most important point for 15.3% respondents out of all the choices presented was the transparency of the philanthropic organization. This means that the philanthropic organization must provide information about the use of the donation. A total of 12% respondents believed that it was essential to ensure relaxed and pleasant communication, and they also indicated that the philanthropic organization must have an impeccable reputation (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Characteristics of the philanthropic organization. Source: created by authors on the basis of survey results in 2022.

For example, the University of Latvia (UL) Foundation specifies this rule of transparency in their donation agreements, where it is indicated that, at any time, the use of a donation allocated to the UL Foundation could be checked by requesting information in order to make sure that the donation allocated was used in accordance with the agreement. Furthermore, the UL Foundation is obliged to provide the patron with the information requested, in order to verify the use of the allocated donation, no later than 10 (ten) working days following the patron’s first request.

A total of 15 respondents considered it equally important that the philanthropic organization must inform donors about the use of the donation at least once a year, that it does not have excessive administrative expenses, and that the philanthropic organization is staffed by professionals. A total of 14 respondents reported that they believe that a previous successful experience with philanthropic organizations is the basis for continuing to donate to specific philanthropic organizations every year. A total of 11 respondents reported that they believe that a philanthropic organization should be respectable. On the other hand, 10 respondents reported that they believe that an important role is played by communication with employees of a philanthropic organization, and the confidence that arises because of negotiations will ensure that this cooperation will succeed. A total of 8 respondents agreed with the statement that the projects of a philanthropic organization should be ambitious and implemented with a high sense of responsibility. Only two respondents indicated that they would like to attend events organized by philanthropic organizations for their patrons. One respondent who chose the possible answer “other” noted that the goals of the donation should be in line with the company’s interests. Most respondents indicated that it was important for them to cooperate with philanthropic organizations that had ensured the transparency of financial flow, had an impeccable reputation, had professional staff, did not have excessive administrative expenses, and provided an overview of their outgoing finances at least once a year. The literature also values the transparency of the philanthropic organization [55], impeccable reputation [56], and pleasant mutual communication [57,58,59,60,61].

4.2. General Fundraising Trends among University Patrons

A correlation was calculated, which indicated a statistically significant correlation between the donations of individuals and legal entities. This will be further discussed below.

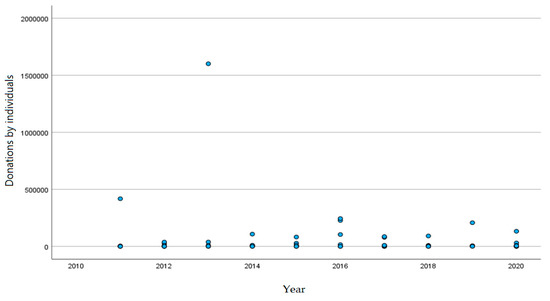

Based on Figure 8, donations from individuals are usually relatively small (smallest mode = €180, average value = €60,645) and are smaller than €500,000.

Figure 8.

Distribution of individual donors’ donations by size and by year. Source: created by authors on the basis of Lursoft database data [62].

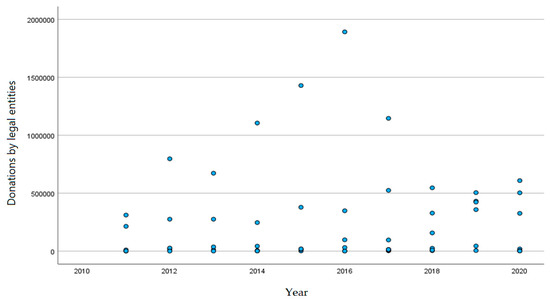

Based on Figure 9, donations from legal entities are usually much larger (mode = €1575, average value = €236,412), but most donations do not exceed €500,000. The situation, in general, does not change significantly over the years.

Figure 9.

Distribution of legal entities donations by size and by year. Source: created by authors on the basis of Lursoft database data [62].

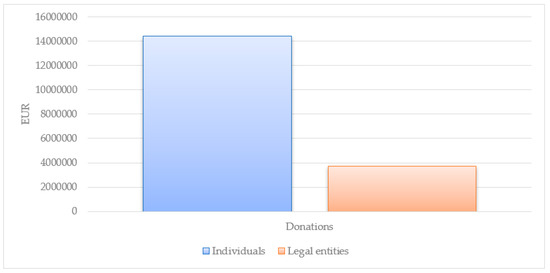

Table 1 shows a comparison of donations from individuals versus donations from legal entities. Pearson’s correlation coefficient and Sig (two-tailed) showed that increasing one does not significantly affect the other. More precisely, if the donations of individuals increase, it does not guarantee that the donations of legal entities will increase, and vice versa. Here, however, the Pearson correlation coefficient was not negative, which indicates that if one of the variables increases, the other variable will also increase (see Figure 10).

Table 1.

Correlation of donations from legal entities and individuals. Source: created by authors.

Figure 10.

Correlation of donations from legal entities. Source: created by authors on the basis of Lursoft database data [62].

Altogether, from 2011 to 2020, philanthropic organizations received €3,699,378 in donations from individuals and €1,4421,165 from legal entities, which totals €1,8120,543. It is clearly visible that the most active donors are legal entities—companies.

In addition, legal entity donors were analyzed. First of all, the correlative relationship between the size of the donation and the annual turnover of the legal entity donor and the duration of its existence, as well as the industry in which it operated, was clarified through correlation analysis. A statistically significant and positive correlation with the amount of the donation was only with the annual turnover of the legal entity donor (0.263, Sign. ≤ 0.01). Analysis of variance with GLM was performed and the main results are shown in the table below—tests of between-subjects effects (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of tests of between-subjects effects. Source: created by authors. Dependent Variable: Donation.

The factor model was not statistically significant (Sign. = 0.729), and it explained only 5.5% of the total variance, as evidenced by the coefficient of determination (Adjusted R Squared = 0.554). As can be seen from the data in the table, neither the industry code, nor the turnover and the duration of the legal entity’s activity or their mutual interaction affected the donation (0.076 > 0.05, 0.667 > 0.05, 0.064 > 0.050.117 > 0.05). According to Levene’s test, the variances of subgroups were different (Sign. < 0.05) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of Levene’s tests of equality of error variances a,b. Source: created by authors.

In general, based on the results of the study, it should be said that philanthropic organizations should work on building feedback with patrons, and providing information on the use of donations and more information on the achievements of the philanthropic organization. Overall, fundraising improves the welfare and sustainability of the organization in the future and is an essential tool in raising funds.

5. Discussion and Future Recommendations

5.1. Contributions to Theory

Many universities around the world depend on financial donations to sustain and improve their operations. Gardner and Pierce (2022) tested their hypotheses using graduates from a private college in the United States, as measured by both the amount and frequency of their donations. Authors found empirical support for a positive relationship between value congruence and commitment, and between commitment and financial donation. However, value congruence was unrelated to giving behavior; normative organizational commitment fully mediated the relationship between assesses congruence and alumni financial giving behavior [63].

One of the most important solutions for achieving the financial viability and sustainability of higher education institutions is the diversification of revenue sources, because the costs associated with ensuring the operation of higher education institutions increases every year. Raising funds through donations for universities presents new challenges that must be faced if the university wants to attract potential donors [2,4,5,6,7].

After analyzing the results collected by various researchers on donation trends and factors influencing donation, it was concluded that the main factors influencing the willingness to donate were education, gender, age, race, income, belonging to a philanthropic organization, motivation to donate, and family status. The wealth of individuals was mentioned as the main determining factor, while additional determining factors included the wealth and prosperity of the city where the individual lives—the richer the city where the donor lives, the larger the private donations for various charitable purposes [22,40].

The literature analysis yielded the conclusion that the donation amount depends on the patron’s free financial resources. Shareholders of companies are interested in polishing their image in society; therefore, they are willing to make donations. Company shareholders, who are also company managers themselves, gladly take pride in the status of being a patron. Furthermore, patronage is a great opportunity to raise the self-confidence of company employees who have directly contributed to the well-being of shareholders with their daily work, even if this is indirectly; therefore, they can also feel like patrons [7,23,24,26,28,30,32].

The relationship between donors and philanthropic organizations is extremely important in terms of successful fundraising; therefore, philanthropic organization must clearly and comprehensibly define the preliminary goals for donations and the possible types of donations. When receiving donations annually and over a long period of time, philanthropic organizations should ensure a more diverse communication flow between the donor and the philanthropic organization, in order to promote sustainability [8,9,17,24,25,27,29,33,55,58].

A demonstration of high administrative expenses on the part of philanthropic organizations repels potential and existing donors, and reduces their desire to donate, as the funds dedicated to covering such administrative expenses should rather be directed to the specific goal of fundraising. Thus, it is important to significantly focus attention on the transparency of the activities of philanthropic organizations, including the amount and necessity of administrative expenses [23].

A practical recommendation for improving the situation in Latvia in the field of donations is to increase tax credits at a national level for donors, both for private individuals and companies.

After analyzing various trends in attracting funds from other countries, it can be concluded that sufficient different studies and data analysis are currently available to advise on fundraising improvement in Latvia. A positive initiative would be philanthropic organizations having more frequent opportunities to go on experience exchange visits, particularly to lean the views of other countries’ representatives regarding how they contribute to the sustainability of philanthropic organizations, as well as to adopt examples of good practice.

5.2. Contributions to Practice

In the case of philanthropic organizations of higher education institutions founded by the state, legal entity companies are more active donors than individuals. Donations from private individuals made up 20% of the total amount and donations from legal entities made up 80% of the total donation amount for the period from 2011 to 2020. This suggests that philanthropic organizations need to invest a greater effort in attracting donations from individuals. Above all, it means more targeted work with graduates. The state-founded philanthropic organizations should focus on the following aspects in their fundraising strategies: administrative expenses should not be exaggerated, the organization must inform patrons about the use of the donation, the philanthropic organization must ensure the transparency of its activities, the organization must be pleasant to communicate with it, and the organization must have an impeccable reputation and professional employees. Philanthropic organizations can count on donations ranging from €15,000 to €50,000 in their fundraising campaigns. As a recommendation, it is necessary to provide more information to the patron about the achievements of the philanthropic organization. Furthermore, since most patrons do not have their own giving strategy, philanthropic organizations need to research potential patrons’ interests and offer them opportunities to support the ideas that are close and relevant to them.

The hypothesis put forward in the article that donations from companies have a much greater advantage than individual donations, has been confirmed. This study will enable philanthropic organizations to improve their fundraising tactics. The data presented in the study and the analysis thereof will enable philanthropic organizations to improve their daily work with donors, both current and prospective.

To determine the experience of high-profile company managers with donations, 14 survey questions were prepared, which provided an insight into the overall fundraising trends and the opportunity to compare them with the data on fundraising trends in the philanthropic organizations of state-founded universities. The respondents were from Business Network International (BNI) Morbergs, which had 50 members at the time of the survey and represents a closed group. To find out what a philanthropic organization should do in order for a company to want to trust it and donate to it, according to the (23) respondents, the most important factor was the transparency of the philanthropic organization. This means that the philanthropic organization must provide information regarding the use of the donation. A total of 18 respondents reported that they believe that it is essential to ensure relaxed and pleasant communication, as well as that the philanthropic organization has an impeccable reputation. Therefore, it can be concluded that a significant driving force for philanthropic organizations is ensuring the successful communication with patrons in order to promote the sustainability of cooperation in the future.

The analysis showed that the assumption that women donate more frequently than men s not confirmed. Most respondents emphasized that the cooperation with philanthropic organizations, so far, met their expectations. Therefore, it should be concluded that philanthropic organizations should work on creating feedback to patrons, providing information about the use of donations and more information about the achievements of the philanthropic organization to strengthen the sustainability of future cooperation.

The responses to the question regarding whether patrons wanted philanthropic organizations to be proud of them in the public space were ambiguous, the respondents did not give an unequivocal answer. Most respondents donated annually. Most of the respondents agreed that the donation improved the image of the company and its reputation. Tax credits were not the determining factor when deciding to donate. Overall, the survey of this exclusive group confirms a positive dynamic in donations. The authors found that if the donation amount by individuals increased, it would not affect the donation amount by legal entities.

Based on the results of the survey, it should be said that entrepreneurs donated more in terms of money than in donations in kind, or by donating their time as volunteers and providing pro bono services—providing high level consultations free of charge. With their donations, entrepreneurs predominantly supported the following donation goals: charity, improving the social well-being of poor and socially vulnerable groups, promoting education, and supporting sports. It was found to be important for patrons that the philanthropic organization ensures the transparency of its activities, is pleasant to communicate with, has an impeccable reputation, has professional employees, does not have excessive administrative expenses, and informs the patron about the use of the donation at least once a year. It should be emphasized that, in general, it is very important for donors that the philanthropic organization ensures the transparency of its operations and is free in terms of communication, which is one of the most important driving forces for the sustainability of the philanthropic organization.

After analyzing the results obtained regarding the main goals of donations among the selected respondents, it should be said that the largest share was attributed to “charity”, which was noted by 19% of respondents. Second place was shared by “improving the social well-being of groups of poor and socially vulnerable persons” and “promotion of education”—14% of respondents. Third place was taken by “supporting sports”—12% of respondents. Fourth place was the “promotion of culture”, indicated by 8% of respondents. Finally, fifth place was shared by several donation goals—“environmental protection”, “promotion of science”, “health promotion”, “disease prevention”, and “civil society development”—at 5%.

On the other hand, when analyzing the motivation to donate, the most important thing among the respondents was the feeling of “satisfaction and joy when donating” (22% of the respondents). The second most important motivation was “the desire to improve the quality of society’s life with your donation” (20% of the respondents), and the third most important was “the desire support a certain area” (20% of respondents).

Sustainability is one of the most pressing research topics driving philanthropic organizations to turn to patron donations for financial support. Therefore, it is essential for philanthropic organizations to improve their fundraising tactics to achieve more successful fundraising.

As part of this research, it was concluded that the donation amount depends on the patron’s free, planned financial resources. Also, patrons are often interested in donating to a noble cause and improving their image.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Recommendations

Limitations of the research: the analyzed data was solely from foundations established by state universities, which have the status of public benefit.

With regard to the improvement in general funding attraction trends among patrons of higher education institutions and businesspeople for promoting the sustainability of higher education institutions in the future, it would be essential to focus and move towards increasing the trend in individual donations, studying related methods that would contribute to the increase in individual donations. In addition, it is considered essential to focus on the development of strategies for creating successful donation campaigns, as well as to promote the role of university management in attracting funds.

6. Conclusions

This study provided a brief overview of the challenges encountered by philanthropic organizations in improving their fundraising tactics. The research data and the analysis thereof will enable philanthropic organizations to improve their daily work with existing and potential donors.

The current study is unique because sustainability problems have been among the most pressing research issues on the agenda of university researchers. This is the main reason why philanthropic organizations seek donations from patrons. However, this field has not yet been examined in detail in Latvia.

The current research is important precisely because of the insufficient funding of higher education, which may significantly impact the sustainability of higher education institutions in the future. This will be an opportunity for philanthropic organizations to improve their work skills, since the result of a successful fundraising campaign depends on careful data analysis. The more patrons that support university researchers, the more knowledge-based research will be created to improve the environment, and thus, the quality of life for society as a whole.

After analyzing the various trends prevailing in other countries regarding fundraising for universities, it can be concluded that a sufficient number of different studies and data analysis are available to enable the comprehensive attraction of funds.

Based on the obtained research results, the authors have arrived at a practical recommendation—in order to improve the situation in Latvia in the field of donations, tax credits for donors, both private individuals and companies, should be increased at the national level.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization—L.K. and L.G.; methodology, L.K. and L.G.; data curation—L.K., B.R., L.G. and P.R., software—L.G. and P.R.; validation—L.K. and P.R.; formal analysis—L.K., L.G., B.R. and P.R.; investigation—L.K., B.R., L.G. and P.R.; writing—preparation of original draft—L.K. and L.G.; writing—review and editing—L.K. and L.G.; visualization—L.G. and P.R.; supervision—L.K. and B.R.; resources—L.K., B.R., L.G. and P.R.; project administration—L.K. and B.R.; funding acquisition—L.K. and B.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies within the program “Strengthening of Scientific Capacity”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data for this study were obtained from the following database: LURSOFT https://www.lursoft.lv/ (accessed on 10 February 2023).

Acknowledgments

This article has been prepared in the framework of the project “Fundraising development trends in state-funded universities in Latvia” funded by the Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies within the program “Strengthening of Scientific Capacity”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Johnstone, D.B. University Revenue Diversification through Philanthropy: International Perspectives. 2016. Available online: http://www.intconfhighered.org/BruceJohnstone.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Sato, M. Education, Ethnicity and Economics: Higher Education Reforms in Malaysia 1957–2003. Nagoya Univ. Commer. Bus. Adm. 2005, 1, 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bloland, H.G. No longer emerging, fundraising is a profession. CASE Int. J. Educ. Adv. 2002, 3, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sirat, M.; Kaur, S. Financing Higher Education: Mapping Public Funding Options. Updates Global High. Educ. 2007, 12, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. Making the Grade 2011: A Study of the Top 10 Issues Facing Higher Education Institutions. 2011. Available online: https://studylib.net/doc/9898111/making-the-grade-2011-a-study-of-the-top-10-issues-facing (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Diamond, A.M., Jr. Does Federal Funding “Crowd In” Private Funding of Science? Contemp. Econ. Policy 1999, 17, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alstete, J.W. Revenue generation strategies: An introduction to revenue origins and changes. ASHE High. Educ. Rep. 2014, 41, 1–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.D. Inventing the Nonprofit Sector and Other Essays on Philanthropy, Voluntarism, and Nonprofit Organizations; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- White, F.L. Creating effective Board-CEO relationships and fundraising to achieve successful student outcomes. New Dir. Community Coll. 2011, 156, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Slyke, D.; Brooks, A. Why do people give? New evidence and strategies for nonprofit managers. Am. Rev. Public 2005, 35, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langseth, M.; McVeety, C. Engagement as a Core University Leadership Position and Advancement Strategy: Perspectives from an Engaged Institution. Int. J. Educ. Adv. 2007, 7, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsien, H.J.L. Why Taiwanese Companies and Foundations Donate to Public Colleges and Universities in Taiwan: An Investigation of Donation Incentives, Strategies, and Decision-Making Processes; Kent State University College: Kent, OH, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, R.A.; File, K.M. The Seven Faces of Philanthropy: A New Approach to Cultivating Major Donors; Jossey-Bass, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S. Nonprofits and public administration: Reconciling performance management and citizen engagement. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2010, 40, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.D. Teaching and research on philanthropy, voluntarism, and nonprofit organizations: A case study of academic innovation. Teach. Coll. Rec. 1992, 93, 403–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drezner, N.D. Philanthropy and Fundraising in American Higher Education; Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chung-Hoon, T.; Hite, J. Organizational integration strategies for promoting enduring donor relations in Higher Education: The value of building inner circle network relationships. Int. J. 2007, 7, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Esparells, C.; Torre, E.M. The Challenge of Fundraising in Universities in Europe. Int. J. High. Educ. 2012, 1, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heger, S.A.; Slonim, R.; Tausch, F.; Tymula, A. Altruism among consumers as donors. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2021, 189, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahone, R.L. Philanthropy versus Fundraising—An Imperative for HBCUs. In Reimagining Historically Black Colleges and Universities: Survival Beyond; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2021; pp. 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Sziegat, H.; Hong, C. University Foundations and Philanthropic Fundraising in Chinese Higher Education: A Promising Trend with Challenge. Int. J. Chin. Educ. 2020, 9, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohayati, M.I.; Youhanna, N.; Williamson, J.C. Philanthropic Fundraising of Higher Education Institutions: A Review of the Malaysian and Australian Perspectives. Sustainability 2016, 8, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baade, R.; Sundberg, J. Fourth Down and Gold to Go? Assessing the Link between Athletics and Alumni Giving. Soc. Sci. Q. 1996, 77, 789–803. [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak, T.; Toubman, S.R. Are Women More Generous than Men? Evidence from Alumni Donations. East. Econ. J. 2012, 39, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransen, F.J. Leveraging philanthropy in Higher Education. Acad. Quest. 2007, 20, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, B.; Morris, S.; Bartkus, B. Comparing Big Givers and Small Givers: Financial Correlates of Corporate Philanthropy. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 45, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, R. Giving Time and/or Money: Trade-off or Spill-over? In Proceedings of the 31st Annual ARNOVA Conference, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–16 November 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rolland, A. What Is the ‘Public Good’? Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, Fresh Perspectives from the World of Philanthropy. 2019. Available online: https://blog.philanthropy.iupui.edu/2019/06/19/what-is-the-public-good/ (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Berman, G.; Davidson, S. Do Donors Care? Some Australian Evidence. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2003, 14, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X.; MacKie-Mason, J. Online Fund-Raising Mechanisms: A Field Experiment. Contrib. Econ. Anal. Policy 2005, 5, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, D.J. “Walking the Walk” of Public Service Motivation: Public Employees and Charitable Gifts of Time, Blood, and Money. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2006, 16, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, R.; Crutzen, O. Just keep it simple: A field experiment on fundraising letters. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2007, 12, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodakarami, F.; Petersen, J.; Venkatesan, R. Developing Donor Relationships: The Role of the Breadth of Giving. J. Mark. 2015, 79, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srnka, K.J.; Grohs, R.; Eckler, I. Increasing Fundraising Efficiency by Segmenting Donors. Australas. Mark. J. 2003, 11, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reece, W.; Zieschang, K. Consistent Estimation of the Impact of Tax Deductibility on the Level of Charitable Contributions. Econometrica 1985, 53, 271–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslaner, E. The Moral Foundations of Trust; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Schervish, P.G. Major donors, major motives: The people and purposes behind major gifts. Philanthr. Fundrais. 2005, 2005, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, J. Why donors give. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 1996, 7, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielefeld, W.; Rooney, P.; Steinberg, K. How Do Need, Capacity, Geography, and Politics Influence Giving? In Gifts of Time and Money: The Role of Charity in Americas Communities; Brooks, A.C., Ed.; Rowman and Littlfield: Lanham, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 127–158. [Google Scholar]

- Mesch, D.J.; Rooney, P.M.; Steinberg, K.S.; Denton, B. The effects of race, gender, and marital status on giving and volunteering in Indiana. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2006, 35, 565–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) Explanation, Formula, and Applications. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/anova.asp (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Hayes, A. Chi-Square (χ2) Statistic: What It Is, Examples, How and When to Use the Test. Investopedia. 2022. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/chi-square-statistic.asp (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Rodgers, J.L.; Nicewander, W.A. Thirteen ways to look at the correlation coefficient. Am. Stat. 1988, 42, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiia, D.H.; Carroll, A.; Buchholtz, A. Philanthropy as Strategy. Bus. Soc. 2003, 42, 169–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, J.C.; Gallagher, G.; Shugart, S.C. More than an open door: Deploying philanthropy to student access and success in American community colleges. New Dir. Stud. Serv. 2010, 2010, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trussel, J.M.; Parsons, L.M. Financial Reporting Factors Affecting Donations to Charitable Not-for-Profit Organizations. Adv. Account. 2003, 23, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J. Recognizing Large Donations to Public Goods: An Experimental Test. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2002, 23, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumru, C.S.; Vesterlund, L. The Effect of Status on Charitable Giving. J. Public Econ. Theory 2010, 12, 709–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamens, D.H. A Theory of Corporate Civic Giving. Sociol. Perspect. 1985, 28, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbaugh, W.T. What do donations buy?—A model of philanthropy based on prestige and warm glow. J. Public Econ. 1998, 67, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, C.-I. Investigating Philanthropy Initiatives in Chinese Higher Education. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2016, 27, 2514–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellew, J.; Goldman, L. Dethroning Historical Reputations: Universities, Museums and the Commemoration of Benefactors; University of London Press: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, N.E. Time Is Money: Choosing between Charitable Activities. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2010, 2, 103–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Posnett, J. Charitable donations by UK households: Evidence from the Family Expenditure Survey. Appl. Econ. 1991, 23, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooks, G.; Sokolic, S. A Case Study for a Successful Donor-Nonprofit Relationship. J. Jew. Communal Serv. 2009, 8412, 132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Caboni, T.C. The Normative Structure of College and University Fundraising Behaviors. J. High. Educ. 2010, 81, 339–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Core, J.E.; Donaldson, T. An Economic and Ethical Approach to Charity and to Charity Endowments. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2010, 68, 261–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedro, I.M.; Pereira, L.N.; Carrasqueira, H.B. Determinants for the commitment relationship maintenance between the alumni and the alma mater. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2018, 28, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]