Does Workplace Spirituality Foster Employee Ambidexterity? Evidence from IT Employees

Abstract

1. Introduction

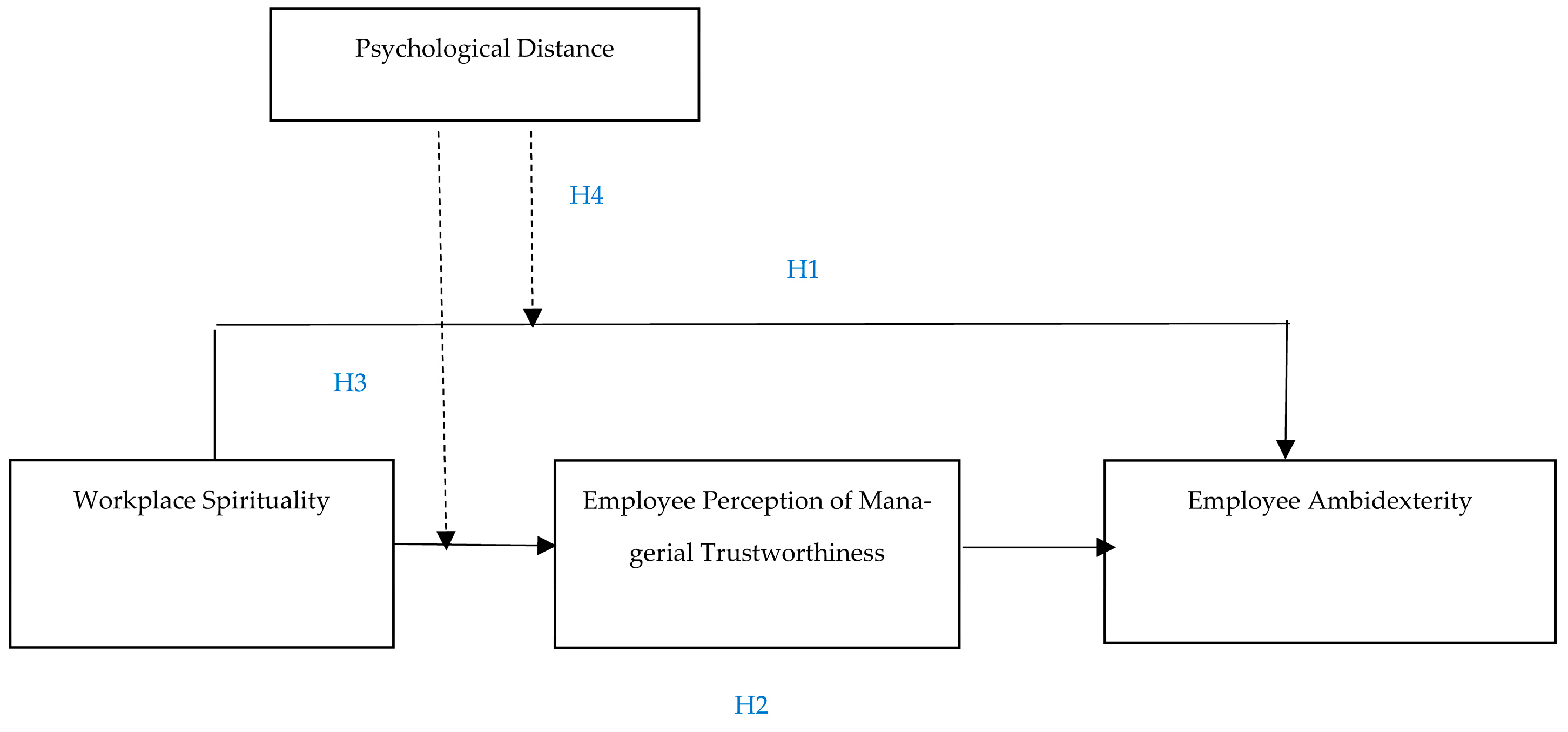

- Research Question (RQ1): Does workplace spirituality foster employee ambidexterity in the IT industry?

- Research Question (RQ2): Does employee perception of managerial trustworthiness mediate the relationship between workplace spirituality and employee ambidexterity in the IT industry?

- Research Question (RQ3): Does psychological distance moderate the relationship between workplace spirituality and employee perception of managerial trustworthiness in the IT industry?

- Research Question (RQ4): Does psychological distance moderate the relationship between workplace spirituality and employee ambidexterity in the IT industry?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Exchange Theory

2.2. Workplace Spirituality and Employee Ambidexterity

Ambidexterity is the ability to both use and refine existing knowledge (exploitation) whilst also creating new knowledge to overcome knowledge deficiencies or absences identified within the execution of the work (exploration).[39] p. 9

2.3. Mediating Role of Employee Perception of Managerial Trustworthiness

2.4. Moderating Role of Psychological Distance

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Sample and Procedures

3.2. Study Tools

4. Results

4.1. Pre-Test and Pilot-Test

4.2. Common Method Bias (CMB)

4.3. Data Analysis and Measurement Model Assessment through Smart-PLS

4.4. Assessment of the Structural Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Managerial Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fernandes Bella, R.L.; Gonçalves Quelhas, O.L.; Toledo Ferraz, F.; Soares Bezerra, M.J. Workplace Spirituality: Sustainable Work Experience from a Human Factors Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraz, Z. Tips on How Employees can Combat Anxiety and Focus on Their Mental Health. Hindustan TimesHindustan Times, 28 January 2023. Available online: http://www.hindustantimes.com/lifestyle/health/tips-on-how-employees-can-combat-anxiety-and-focus-on-their-mental-health-101674899283453.html (accessed on 13 May 2023).

- Lips-Wiersma, M.; Mills, A.J. Understanding the Basic Assumptions about Human Nature in Workplace Spirituality: Beyond the Critical versus Positive Divide. J. Manag. Inq. 2014, 23, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashmos, D.P.; Duchon, D. Spirituality at Work: A Conceptualization and Measure. J. Manag. Inq. 2000, 9, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahnke, K.; Giacalone, R.A.; Jurkiewicz, C.L. Point-counterpoint: Measuring Workplace Spirituality. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2003, 16, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulphey, M.M. A Meta-Analytic Literature Study on the Relationship Between Workplace Spirituality and Sustainability. J. Relig. Health 2022, 61, 4674–4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahipalan, M.; Sheena, S. Workplace Spirituality, Psychological Well-Being and Mediating Role of Subjective Stress: A Case of Secondary School Teachers in India. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2019, 35, 725–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belwalkar, S.; Vohra, V.; Pandey, A. The Relationship between Workplace Spirituality, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors–an Empirical Study. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 14, 410–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Jena, L.K.; Sahoo, K. Workplace Spirituality and Workforce Agility: A Psychological Exploration Among Teaching Professionals. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldorai, K.; Kim, W.G.; Chang, H.; Li, J. Workplace Spirituality as a Mediator between Ethical Climate and Workplace Deviant Behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 86, 102372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beekun, R.I.; Badawi, J.A. Balancing Ethical Responsibility among Multiple Organizational Stakeholders: The Islamic Perspective. J. Bus. ethics 2005, 60, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geigle, D. Workplace spirituality empirical research: A literature review. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2012, 2, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Adnan, N.; Bhatti, O.K.; Farooq, W. Relating Ethical Leadership with Work Engagement: How Workplace Spirituality Mediates? Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1739494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASSCOM. The IT-BPM Industry in India 2017: A Strategic Review; NASSCOM: Noida, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nazir, T. About 43% Indian Employees in Private Sector Suffer from Mental Health Issues at Workplace: Study. The Logical Indian, 30 November 2021. Available online: https://thelogicalindian.com/mentalhealth/43-indian-employeesprivate-sector-suffer-from-mental-health-issues-32308?infinitescroll=1 (accessed on 13 May 2023).

- Iqbal, M.; Adawiyah, W.R.; Suroso, A.; Wihuda, F. Exploring the Impact of Workplace Spirituality on Nurse Work Engagement: An Empirical Study on Indonesian Government Hospitals. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2020, 36, 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, I.; Khan, J.; Zada, M.; Ullah, R.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Contreras-Barraza, N. Towards Examining the Link between Workplace Spirituality and Workforce Agility: Exploring Higher Educational Institutions. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.K.; Kumra, R. Relationship between Workplace Spirituality, Organizational Justice and Mental Health: Mediation Role of Employee Engagement. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2020, 17, 627–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantha, T.; Nayak, U. The Relation of Workplace Spirituality with Employees’ Innovative Work Behaviour: The Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2021, 13, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mom, T.J.M.; Van Den Bosch, F.A.J.; Volberda, H.W. Understanding Variation in Managers’ Ambidexterity: Investigating Direct and Interaction Effects of Formal Structural and Personal Coordination Mechanisms. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 812–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniëls, M.C.J.; Veld, M. Employee Ambidexterity, High Performance Work Systems and Innovative Work Behaviour: How Much Balance Do We Need? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 30, 565–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napier, B.J.; Ferris, G.R. Distance in Organizations. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1993, 3, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, D. A Note on Psychological Distance and Export Market Selection. J. Int. Mark. 2000, 8, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantha, T.; Nayak, U. The Relation of Workplace Spirituality with Employee Creativity among Indian Software Professionals: Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment. South Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junni, P.; Sarala, R.M.; Taras, V.A.S.; Tarba, S.Y. Organizational Ambidexterity and Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H.; Robinson, A.J.; Rosing, K. Ambidextrous Leadership and Employees’ Self-reported Innovative Performance: The Role of Exploration and Exploitation Behaviors. J. Creat. Behav. 2016, 50, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtner, S.; Reinhardt, R. Ambidextrous Idea Generation—Antecedents and Outcomes. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2016, 33, 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnellbächer, B.; Heidenreich, S.; Wald, A. Antecedents and Effects of Individual Ambidexterity–A Cross-Level Investigation of Exploration and Exploitation Activities at the Employee Level. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Social Exchange. Int. Encycl. Soc. Sci. 1968, 7, 452–457. [Google Scholar]

- Homans, G.C. The Humanities and the Social Sciences. Am. Behav. Sci. 1961, 4, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audenaert, M.; Decramer, A.; Lange, T.; Vanderstraeten, A. Setting High Expectations Is Not Enough. Int. J. Manpow. 2016, 37, 1024–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Li, J.; Mao, Z.E.; Lu, Z. Can Ethical Leadership Inspire Employee Loyalty in Hotels in China?-From the Perspective of the Social Exchange Theory. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 49, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliman, J.; Czaplewski, A.J.; Ferguson, J. Workplace Spirituality and Employee Work Attitudes: An Exploratory Empirical Assessment. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2003, 16, 426–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, N. Workplace Spirituality and Employee Well-Being: An Empirical Exploration. J. Hum. Values 2017, 23, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Zamor, J. Workplace Spirituality and Organizational Performance. Public Adm. Rev. 2003, 63, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodinsky, R.W.; Giacalone, R.A.; Jurkiewicz, C.L. Workplace Values and Outcomes: Exploring Personal, Organizational, and Interactive Workplace Spirituality. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, B.S. Individual Spirituality, Workplace Spirituality and Work Attitudes: An Empirical Test of Direct and Interaction Effects. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2009, 30, 759–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, S.; Jamal, T. In Search of Spiritual Workplaces: An Empirical Evidence Of Workplace Spirituality And Employee Performance In The Indian IT Industry. Inter. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 9, 1116–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Jena, L.K. Does Workplace Spirituality Lead to Raising Employee Performance? The Role of Citizenship Behavior and Emotional Intelligence. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2022, 30, 1309–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.; Swart, J.; Maylor, H. Mechanisms for Managing Ambidexterity: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertusa-Ortega, E.M.; Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Tarí, J.J.; Pereira-Moliner, J.; López-Gamero, M.D. The Microfoundations of Organizational Ambidexterity: A Systematic Review of Individual Ambidexterity through a Multilevel Framework. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2020, 24, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, F.; Van Horne, C. Individual ambidexterity and antecedents In A Changing Context. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 23, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Snell, S.A. Intellectual Capital Architectures and Ambidextrous Learning: A Framework for Human Resource Management. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 65–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.B.; Birkinshaw, J. The Antecedents, Consequences, and Mediating Role of Organizational Ambidexterity. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniëls, M.C.J.; Neghina, C.; Schaetsaert, N. Ambidexterity of Employees: The Role of Empowerment and Knowledge Sharing. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 1098–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Smith, K.G.; Shalley, C.E. The Interplay between Exploration and Exploitation. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, F.; Guest, D.; Ramos, J.; Gracia, F.J. High Commitment HR Practices, the Employment Relationship and Job Performance: A Test of a Mediation Model. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.T.M.; Liu, G.; Ko, W.W.; Curtis, A. Harmonious Workplace Climate and Employee Altruistic Behavior: From Social Exchange Perspective. Int. J. Manpow. 2021, 42, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Manage. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.J.; Perry, J.L. Intrinsic Motivation and Employee Attitudes: Role of Managerial Trustworthiness, Goal Directedness, and Extrinsic Reward Expectancy. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2012, 32, 382–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner-Marsh, F.; Conley, J. The Fourth Wave: The Spiritually-based Firm. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 1999, 12, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Bin Nadeem, A.; Akhter, A. Impact of Workplace Spirituality on Job Satisfaction: Mediating Effect of Trust. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2016, 3, 1189808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, J. Socializing a Capitalistic World: Redefining the Bottom Line. J. Am. Acad. Bus. 2005, 7, 283–287. [Google Scholar]

- Dirks, K.T.; Ferrin, D.L. The Role of Trust in Organizational Settings. Organ. Sci. 2001, 12, 450–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Sumanth, J.J. Mission Possible? The Performance of Prosocially Motivated Employees Depends on Manager Trustworthiness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapierre, L.M. Supervisor Trustworthiness and Subordinates’ Willingness to Provide Extra-Role Efforts 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 272–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldner, A.W. The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.; Han, T.; Chuang, J. The Relationship between High-commitment HRM and Knowledge-sharing Behavior and Its Mediators. Int. J. Manpow. 2011, 32, 604–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagil, D. Charismatic Leadership and Organizational Hierarchy: Attribution of Charisma to Close and Distant Leaders. Leadersh. Q. 1998, 9, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkutlu, H.; Chafra, J. Leader Machiavellianism and Follower Silence: The Mediating Role of Relational Identification and the Moderating Role of Psychological Distance. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 28, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Story, J.S.P.; Barbuto Jr, J.E. Global Mindset: A Construct Clarification and Framework. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2011, 18, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.J. Compassion Momentum Model in Supervisory Relationships. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2017, 27, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, S. Measuring the Psychological Distance between an Organization and Its Members—The Construction and Validation of a New Scale. Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Klerk, J.J.; Boshoff, A.B.; Van Wyk, R. Spirituality in Practice: Relationships between Meaning in Life, Commitment and Motivation. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 2006, 3, 319–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, J.L. Workplace Spirituality and Stress: Evidence from Mexico and US. Manag. Res. Rev. 2015, 38, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mom, T.J.M.; Van Den Bosch, F.A.J.; Volberda, H.W. Investigating Managers’ Exploration and Exploitation Activities: The Influence of Top-down, Bottom-up, and Horizontal Knowledge Inflows. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 44, 910–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nitzl, C.; Roldan, J.L.; Cepeda, G. Mediation Analysis in Partial Least Squares Path Modeling: Helping Researchers Discuss More Sophisticated Models. Ind. Manag. data Syst. 2016, 116, 1849–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM: A Full Collinearity Assessment Approach. Int. J. e-Collaboration 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: A Comparative Evaluation of Composite-Based Structural Equation Modeling Methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Mitchell, R.; Gudergan, S.P. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling in HRM Research. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 1617–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. Cross-validatory choice and assessment of statistical predictions. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1974, 36, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnakumar, S.; Neck, C.P. The “What”, “Why” and “How” of Spirituality in the Workplace. J. Manag. Psychol. 2002, 17, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J.B. Some problems and misconceptions related to the construct of internal versus external control of reinforcement. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1975, 43, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.H.; Lim, A.K.H. Trust in coworkers and trust in organizations. J. Psychol. 2009, 143, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palframan, J.T.; Lancaster, B.L. Workplace spirituality and person–organization fit theory: Development of a theoretical model. J. Human Values 2019, 25, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Info | Categories | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 20–30 | 92 | 23.96 |

| 31–40 | 110 | 28.65 | |

| 41–50 | 148 | 38.54 | |

| 51–60 | 34 | 8.85 | |

| Experience | less than 5 years | 102 | 26.56 |

| 5 to 10 years | 110 | 28.65 | |

| 11 years 15 years | 145 | 37.76 | |

| more than 15 years | 27 | 7.03 | |

| Gender | Male | 187 | 48.70 |

| Female | 197 | 51.30 | |

| Designation | Help desk technician | 66 | 17.19 |

| IT technician | 47 | 12.24 | |

| Web developer | 58 | 15.10 | |

| System administrator | 69 | 17.97 | |

| System analyst | 44 | 11.46 | |

| Others | 100 | 26.04 |

| Variables | Mean | SD | Age | Exper. | Gender | Design. | WS | PD | EPMT | EA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 2.323 | 0.937 | 1 | |||||||

| Experience | 2.253 | 0.929 | 0.038 | 1 | ||||||

| Gender | 1.513 | 0.500 | 0.063 | 0.057 | 1 | |||||

| Desig. | 3.724 | 1.810 | 0.030 | 0.021 | 0.062 | 1 | ||||

| WS | 3.809 | 0.777 | 0.216 ** | 0.022 | 0.012 | 0.078 | 1 | |||

| PD | 3.753 | 0.811 | 0.186 ** | −0.022 | 0.029 | 0.000 | 0.526 ** | 1 | ||

| EPMT | 3.461 | 0.804 | 0.127 * | 0.054 | −0.046 | 0.044 | 0.330 ** | 0.371 ** | 1 | |

| EA | 3.963 | 0.783 | 0.175 ** | 0.091 | 0.107 * | −0.022 | 0.277 ** | 0.217 ** | 0.299 ** | 1 |

| Constructs | Items | FL | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA | EA01 | 0.809 | 0.942 | 0.950 | 0.657 |

| EA02 | 0.793 | ||||

| EA03 | 0.818 | ||||

| EA04 | 0.820 | ||||

| EA05 | 0.800 | ||||

| EA06 | 0.820 | ||||

| EA07 | 0.860 | ||||

| EA08 | 0.799 | ||||

| EA09 | 0.782 | ||||

| EA10 | 0.803 | ||||

| EPMT | EMPT04 | 0.827 | 0.863 | 0.901 | 0.645 |

| EPMT01 | 0.814 | ||||

| EPMT02 | 0.802 | ||||

| EPMT03 | 0.801 | ||||

| EPMT05 | 0.771 | ||||

| PD | PD01 | 0.877 | 0.837 | 0.902 | 0.754 |

| PD02 | 0.856 | ||||

| PD03 | 0.871 | ||||

| WS | WS02 | 0.787 | 0.905 | 0.923 | 0.571 |

| WS03 | 0.794 | ||||

| WS04 | 0.833 | ||||

| WS05 | 0.755 | ||||

| WS06 | 0.808 | ||||

| WS07 | 0.715 | ||||

| WS08 | 0.658 | ||||

| WS09 | 0.664 | ||||

| WS01 | 0.768 |

| Fornell–Larcker | HTMT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constructs | EA | EPMT | PD | WS | EA | EPMT | PD | WS |

| EA | 0.811 | |||||||

| EPMT | 0.304 | 0.803 | 0.332 | |||||

| PD | 0.222 | 0.374 | 0.868 | 0.245 | 0.437 | |||

| WS | 0.284 | 0.333 | 0.527 | 0.756 | 0.303 | 0.373 | 0.606 | |

| R-Square | Endogenous Variables | R Square | R Square Adjusted | 0.26: Substantial, 0.13: Moderate, 0.02: Weak [72]) |

| EA | 0.140 | 0.131 | ||

| EPMT | 0.166 | 0.159 | ||

| Effect Size (F-Square) | Exogenous Variables | EA | EPMT | 0.35: Substantial, 0.15: Medium effect, 0.02: Weak effect [72] |

| EPMT | 0.049 | |||

| WS | 0.028 | 0.030 | ||

| Colinearity (Inner VIF) | Exogenous Variables | EA | EPMT | VIF ≤ 5.0 [73] |

| EPMT | 1.199 | |||

| WS | 1.428 | 1.386 | ||

| Predictive Relevance (Q-Square) | Endogenous Variables | CCR | CCC | Value higher than o indicates Predictive Relevance [74] |

| EA | 0.087 | 0.577 | ||

| EPMT | 0.102 | 0.463 |

| Hypotheses | OS/Beta | SD | 95% C.I. Bias Corrected | T | P | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||||

| H1: WS → EA | 0.184 | 0.056 | 0.070 | 0.278 | 3.291 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H2: WS → EPMT → EA | 0.042 | 0.017 | 0.012 | 0.078 | 2.428 | 0.016 | Supported |

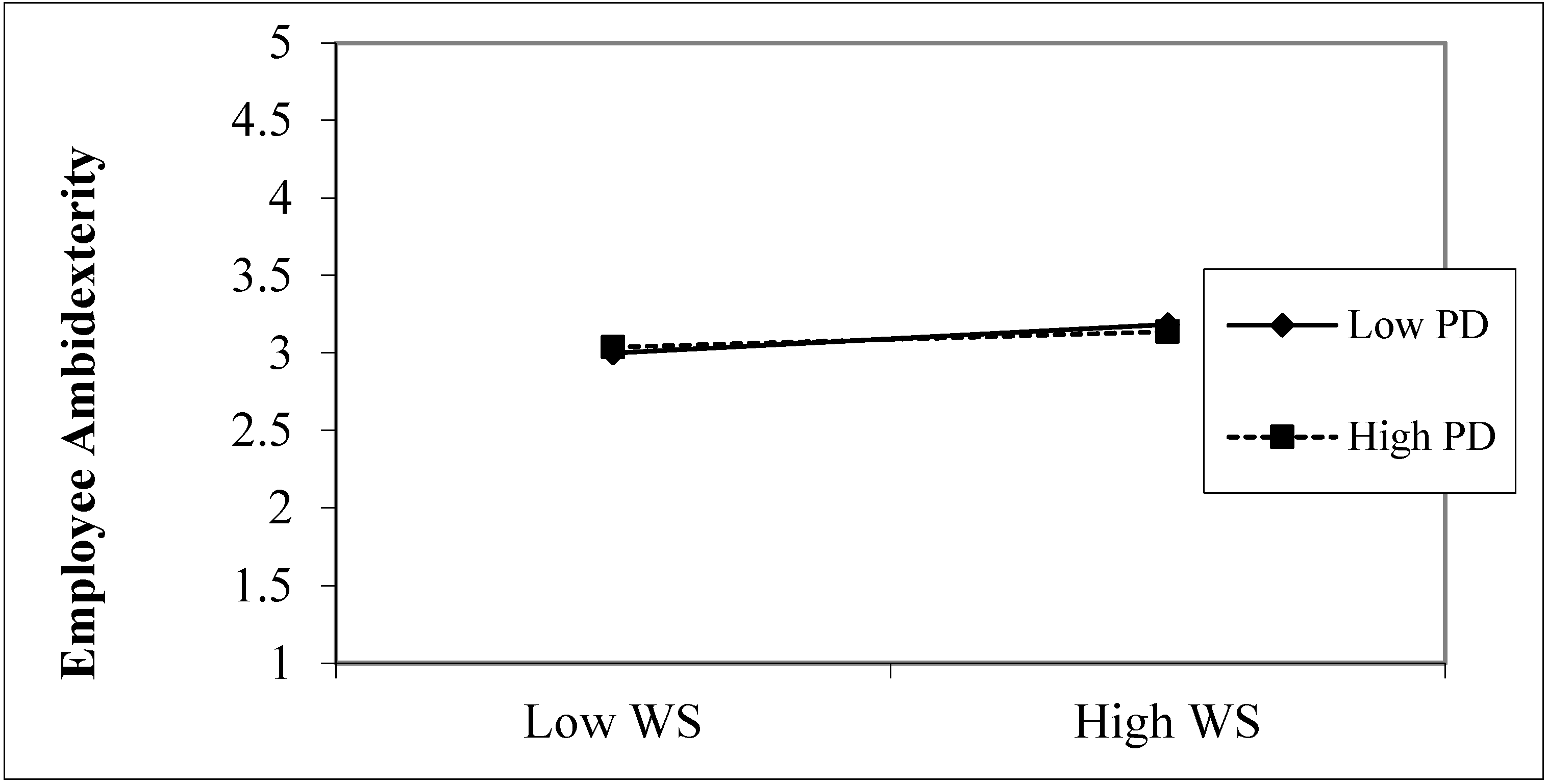

| H3: PD × WS → EPMT | −0.022 | 0.052 | −0.126 | 0.072 | 0.429 | 0.668 | Not Supported |

| H4: PD × WS → EA | −0.081 | 0.041 | −0.155 | 0.005 | 1.971 | 0.049 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alam, M.N.; Iqbal, J.; Alotaibi, H.S.; Nguyen, N.T.; Mat, N.; Alsiehemy, A. Does Workplace Spirituality Foster Employee Ambidexterity? Evidence from IT Employees. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11190. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411190

Alam MN, Iqbal J, Alotaibi HS, Nguyen NT, Mat N, Alsiehemy A. Does Workplace Spirituality Foster Employee Ambidexterity? Evidence from IT Employees. Sustainability. 2023; 15(14):11190. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411190

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlam, Mohammad Nurul, Juman Iqbal, Hammad S. Alotaibi, Nhat Tan Nguyen, Norazuwa Mat, and Ali Alsiehemy. 2023. "Does Workplace Spirituality Foster Employee Ambidexterity? Evidence from IT Employees" Sustainability 15, no. 14: 11190. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411190

APA StyleAlam, M. N., Iqbal, J., Alotaibi, H. S., Nguyen, N. T., Mat, N., & Alsiehemy, A. (2023). Does Workplace Spirituality Foster Employee Ambidexterity? Evidence from IT Employees. Sustainability, 15(14), 11190. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411190