Commercial Culture as a Key Impetus in Shaping and Transforming Urban Structure: Case Study of Hangzhou, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data Resources and Methods

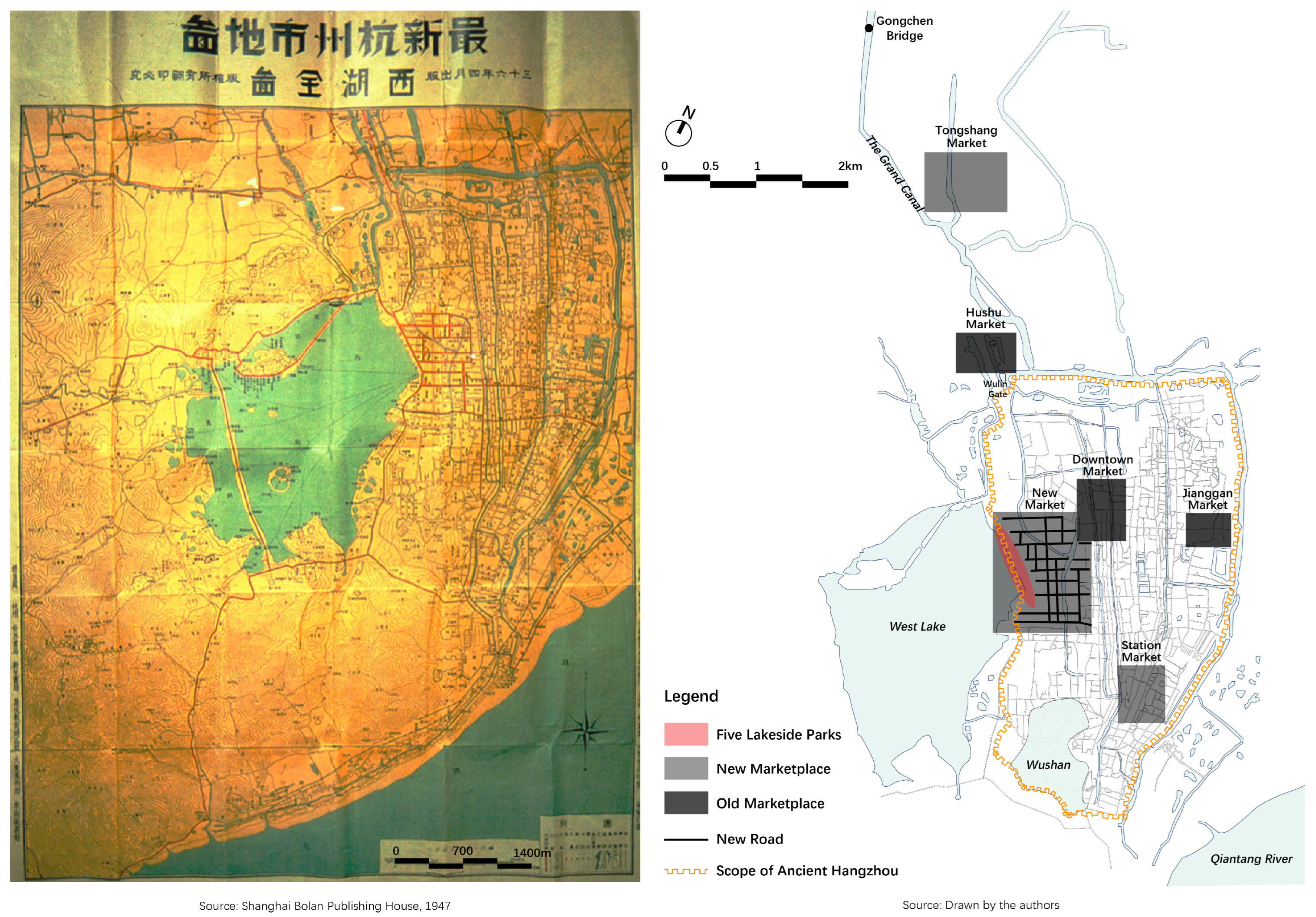

3. Transformation 1: Lin’an in the Southern Song Dynasty, 1137–1279

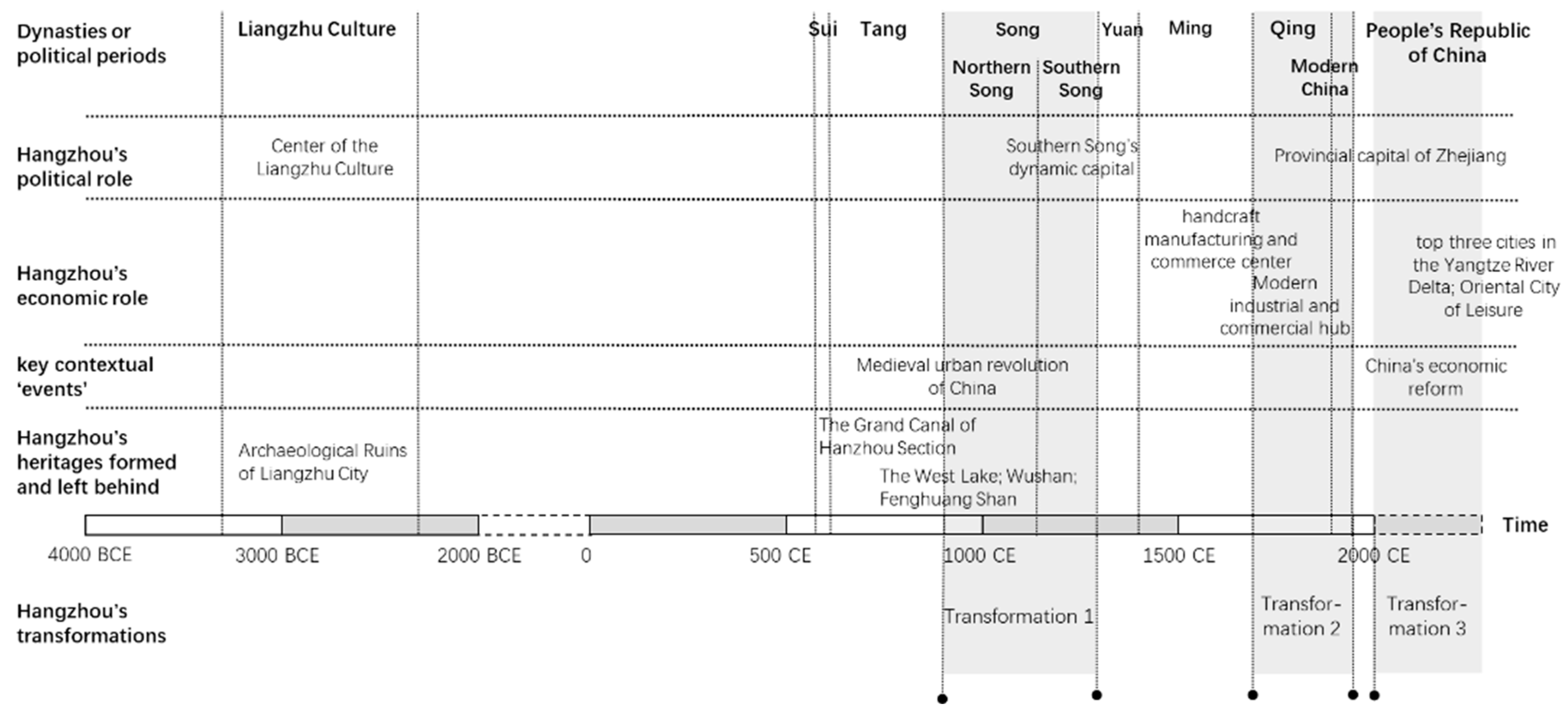

3.1. General Urban Structure before and after the Song Dynasty

3.1.1. Li-Fang System

3.1.2. Fang-Xiang System

3.2. Comparison between Chang′an and Lin’an

- City name

- Urban planning

- Markets and subsidiary facilities

- Recreational places

- Scenic areas

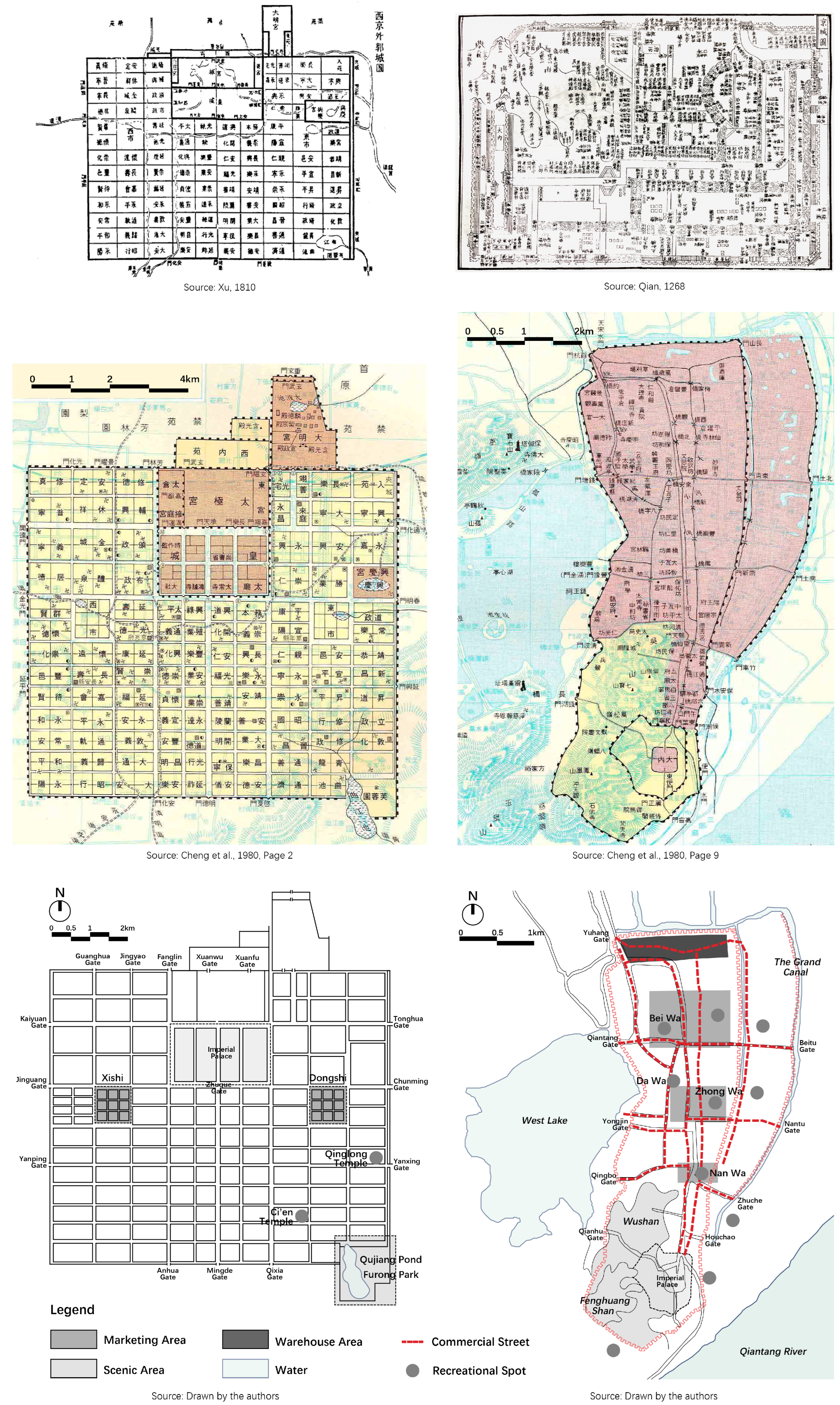

4. Transformation 2: Hangzhou in the Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China, 1636–1940s

4.1. Hangzhou in Ming and Early Qing Dynasty

4.1.1. Silk Culture as the Commercial Culture

4.1.2. Tea Culture as the Leisure Culture

4.2. Hangzhou in the Late-Qing and Early Twentieth Century

4.2.1. Modern Industrial and Commercial Culture

4.2.2. Landscape Culture

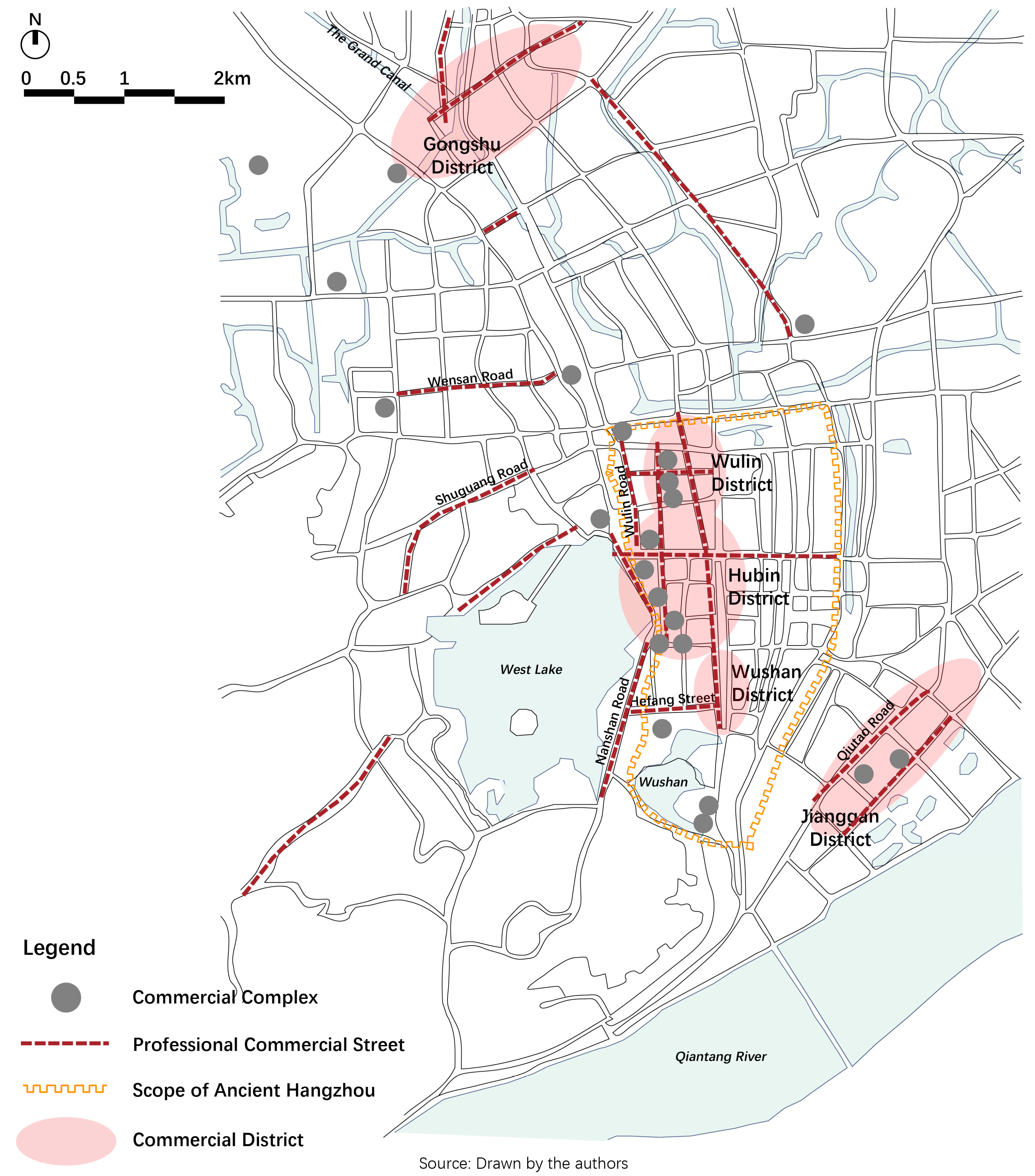

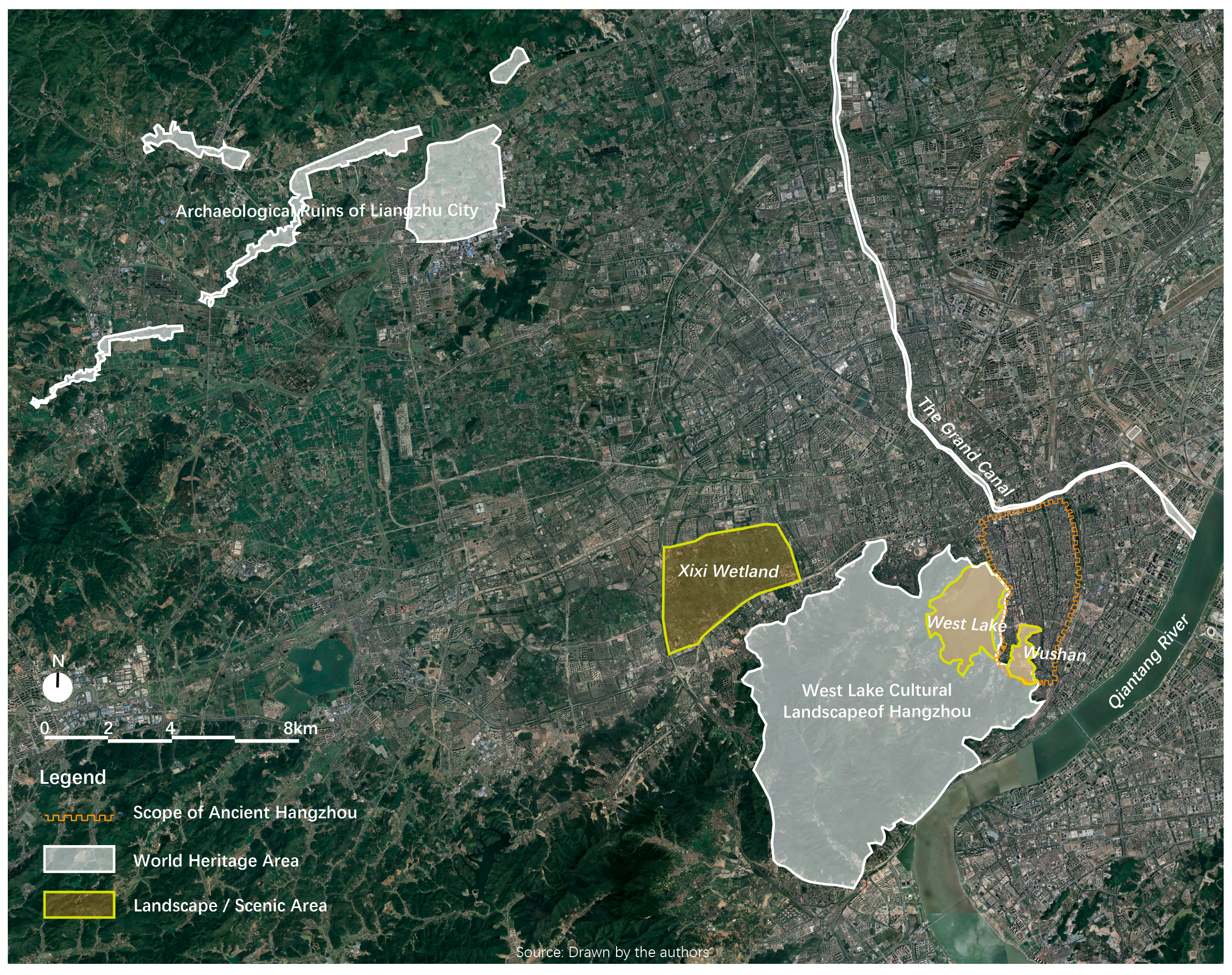

5. Transformation 3: Present Day Hangzhou, 1980s Onwards

5.1. New Elements of Commercial Culture

5.2. Leisure and Heritage Culture

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lincoln, T. An Urban History of China; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Barbera, L.; Monaco, A.I.D. Hangzhou. The Contemporary Challenges of a former Capital of Imperial China. L’architettura Delle città. J. Sci. Soc. Ludovico Quaroni 2017, 7, 5–63. [Google Scholar]

- de Pee, C.; Lam, J.S.C. Introduction, in Senses of the City: Perceptions of Hang-zhou and Southern Song China; Lam, J.S.C., Lin, S., de Pee, C., Eds.; The Chinese University Press: Hong Kong, China, 2017; pp. xiii–xxv. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, G.W. Introduction: Urban development in imperial China. In The City in Late Imperial China; Skinner, G.W., Ed.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1977; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Shiba, Y. Tyugoku Toshishi; University of Tokyo Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K. An Institutioanl History of Chinese Ancient Capital Cities; Shanghai People′s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schinz, A. The Magic Squre: Cities in Ancient China; Edition Axel Menges: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, V.C. Capital Cities and Urban Form in Pre-Modern China Luoyang, 1038 BCE to 938 CE.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, F. Study on the Form, Structure, and Layout of Song to Qing Dynasty’s Capital Cities; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q. The Archaeological Discovery and Research of Ancient Chinese Capital; Social Sciences Literature Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, C.; Kesteloot, C. Beijing′s Socio-Spatial Structure in Transition. In Studies in Segregation and Desegregation; Ostendorf, W., Schnell, I., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; pp. 27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, K. Evolution of Urban Socio-Spatial Structure in Modern Times in Xi’an, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, V.C. Sui-Tang Chang′an: A Study in the Urban History of Medieval China; Michigan Center for Chinese Studies, The University of Michigan: AnArbor, MI, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, T. A Comparative Capital City History of Sui-tang Chang′an and the Estern Asia; Northwest University Press: Xi′an, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Yang, S. A Comparison of Urban Planning in Eastern Asian Capitals during Japanese Colonial Rule: Tokyo, Taipei (1895), Seoul (1910), and Beijing (1936). Sustainability 2023, 15, 4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, H.; Chen, J.; He, Q.; Liu, Z. Spatio-temporal evolution analysis of spatial form in Nanfeng based on spatial syntax. Ann. GIS 2023, 29, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Hua, C. Multi-Scale Urban Spatial Evolution Analysis Based on Space Syntax: A Case Study in Modern Yangzhou, China. Int. J. Archit. Environ. Eng. 2019, 13, 345–352. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Q. Analysis Of the Evolution of Urban Form in Modern Hefei City and Its Dynamics Mechanism. Highlights in Science. Eng. Technol. 2023, 51, 175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, H.; Xu, S.; Aoki, N. Analysis of the Spatial and Temporal Distribution and Reuse of Urban Industrial Heritage: The Case of Tianjin, China. Land 2022, 11, 2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Du, J.; Kuang, J.; Chen, C.; Li, M.; Wang, J. Two-Scaled Identification of Landscape Character Types and Areas: A Case Study of the Yunnan–Vietnam Railway (Yunnan Section), China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mote, F.W. A millennium of Chinese urban history: Form, time and space concepts in Soochow. Rice Univ. Stud. 1973, 59, 35–65. [Google Scholar]

- Southall, A. The City in Time and Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F. Hangzhou in the Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties; Zhejiang People’s Publishing House: Hangzhou, China, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, S. Shan-shui myth and history: The locally planned process of combining the ancient city and West Lake in Hangzhou, 1896–1927. Plan. Perspect. 2016, 31, 363–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X. The Rise of West Lake: A Cultural Landmark in the Song Dynasty; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q. Post-reform under restructuring in China: The case of Hangzhou 1990–2010. Town Plan. Rev. 2012, 83, 431–455. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q. Hangzhou. Cities 2015, 48, 42–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. Urban Space and Tourism in the Social Transformation of Hangzhou; University of California: San Diego, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.D.; Fang, C. Urban expansion and land use restructuring in Hangzhou, China. Asian Geogr. 2003, 22, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Jin, P. Formation of the modern scenic city of Hangzhou: Towards conservation integrated urban planning, 1950s–1990s. Built Herit. 2020, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. Tourism and spatial change in Hangzhou, 1911–1927. In Remaking the Chinese City: Modernity and National Identity, 1900–1950; Esherick, J.W., Ed.; University of Hawai’i Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2000; pp. 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Esherick, J.W. Modernity and Nation in the Chinese City. In Remaking the Chinese City: Modernity and National Identity, 1900–1950; Esherick, J.W., Ed.; University of Hawai’i Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2000; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X. Landscape urbanism: Urban-rural relations in Hangzhou of Southern Song China. In Routledge Handbook of Chinese Architecture; Zhu, J., Wei, C., Hua, L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 143–158. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Pan, Y.; Dong, N.; Storozum, M. The rise and fall of the Liangzhu society in the perspective of subsistence economy. Chin. Archaeol. 2022, 22, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cheng, H.; Sinha, A.; Spötl, C.; Cai, Y.; Liu, B.; Kathayat, G.; Li, H.; Tian, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Collapse of the Liangzhu and other Neolithic cultures in the lower Yangtze region in response to climate change. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabi9275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Y.; Liu, B.; Qin, L. Liangzhu Culture: Society, Belief, and Art in Neolithic China; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, J.S.C.; Lin, S.; de Pee, C.; Powers, M. Senses of the City: Perceptions of Hangzhou & Southern Song China 1127–1279; The Chinese University of Hong Kong: Hong Kong, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M. Gazetteer of Chang′an. Available online: https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&res=457201&remap=gb (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Xu, S. Research of Blocks in Two Ancient Capital Cities (Xi’an and Luoyang) of Tang Dynasty; Sanqin Publishing House: Xi’an, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Y. The Dream of Hua in the Eastern Capital. Available online: https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&res=712358&remap=gb (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- The Old Man of West Lake. Record of Luxuriant Scenery by the Old Man of West Lake. Available online: https://www.zhonghuadiancang.com/tianwendili/10694/ (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Ni, D. A Record of the Capital’s Famous Scenic Spots. Available online: https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&res=178091&remap=gb (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Qian, Y. Gazetteer of Lin’an from the Xianchun Reign Period. Available online: https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&res=258802&remap=gb (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Zhou, M. Former Matters of Wulin. Available online: https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&res=24518&remap=gb (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Wu, Z. Dream of Hangzhou; Zhejiang People’s Publishing House: Hangzhou, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Xia, S. The Government Record of Hangzhou from the Chenghua Reign Period; Available online: https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&res=7435959&remap=gb (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Wang, S.; Cui, K.; Wang, K. Study On Supplementary Drawing of Lv Dafang’s ‘Chang′an City Map’ In the Northern Song Dynasty. City Plan. Rev. 2016, 40, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, G. Atlas of Chinese History; Chinese Cultural Institute Press: Taibei, China, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Pan, J.; Zhu, X. Analysis of Development Features of Dongjing’s Commercial Space in Northern Song Dynasty: Based on Interpretation of Drawing of Riverside Scene at Qingming Festival. City Plan. Rev. 2013, 37, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Que, W. Hangzhou City and Xihu History in Diagrams; Zhejiang People’s Publishing House: Hangzhou, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- The Office of Hangzhou Municipal Government. Atlas of Hangzhou; Sinomap Press: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J. A Study of Administrative Cities in Jiangnan since Ming Dynasty; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. The Ancient Capitals and Cities in Chinese History; Jiangsu People’s Publishing House: Nanjing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q. A Restoration Study of The Song Version ‘Gazetteer of Lin’an from the Xianchun Reign Period’s Four Capital City Maps; Shanghai Classics Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Moll-Murate, C. State and Crafts in the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911); Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H. Research on the Early Urban Modernization of Hangzhou: 1896–1927; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, W. Urban Study of the Song Dynasty; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Benn, J.A. Tea in China: A Religious and Cultural History; University of Hawai’i Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, D.; Wu, J.; Xu, S. An Architecture History of Modern China, Vol 2: Plural Exploration: The Modernization All Over the Country in the Early Republic of China and the Development of China’s Architecture Science; China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuan, T. World Leisure Expo for a Healthier Life. 2011. Available online: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/regional/2011-09/17/content_13746996.htm (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Wheatley, P. The Origins and Character of the Chinese City; Routledge: Abingdon, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, C.; Cao, W. An Urban History of China; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| City | Text Name | Author | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tang Chang′an | Gazetteer of Chang′an [38] | Song Minqiu (宋敏求) | 1076 |

| Research of Blocks in Two Ancient Capital Cities (Xi’an and Luoyang) of Tang Dynasty [39] | Xu Son (徐松) | 1810 | |

| Song Dongjing | The Dream of Hua in the Eastern Capital [40] | Meng Yuanlao (孟元老) | 1127 |

| Southern Song Lin’an | Record of Luxuriant Scenery by the Old Man of West Lake [41] | The Old Man of West Lake (西湖老人) | 12th century |

| A Record of the Capital’s Famous Scenic Spots [42] | Ni Deweng (耐得翁) | 1235 | |

| Gazetteer of Lin’an from the Xianchun Reign Period [43] | Qian Yueyou (潜说友) | 1268 | |

| Former Matters of Wulin [44] | Zhou Mi (周密) | 1290 | |

| Dream of Hangzhou [45] | Wu Zimu (吴自牧) | 1334 | |

| Ming and Qing Hangzhou | The Government Record of Hangzhou from the Chenghua Reign Period [46] | Chen Rang (陈让), Xia Shizheng (夏时正) | 1465–1487 |

| City | Historic Maps or Painting | Base Maps | Satellite Maps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tang Chang′an | Lv Dafang (吕大防), Chang′an City Map (长安图), 1080 [47] | Cheng Guangyu, Map of Tang Chang′an City [48] | / |

| Xu Son, Map of the Western Capital, ‘Research of Blocks in Two Ancient Capital Cities (Xi’an and Luoyang) of Tang Dynasty’, 1810 [39] | |||

| Song Dongjing | Zhang Zeduan (张择端), Riverside Scenes at the Qingming Festival (清明上河图), 1101 [49] | / | / |

| Southern Song Lin’an | Qian Yueyou, Map of the Southern Song Capital Lin’an, 1268 [43] | Cheng Guangyu, Map of Southern Song Lin’an City [48] | / |

| Qing Hangzhou | / | Zhejiang Map Bureau, Map of Zhejiang Provincial Capital, 1892 [50] | / |

| Hangzhou in the early twentieth century | / | Shanghai Bolan Publishing House, Latest Hangzhou City Map: Full Map of West Lake, 1947 [50] | / |

| Contemporary Hangzhou | / | The Office of Hangzhou Municipal Government, Map of the Eight Districts of Hangzhou [51] | Google Earth |

| Tang Chang′an | Southern Song Lin’an | |

|---|---|---|

| Role | Capital city of the Tang Dynasty and other twelve dynasties | The Southern Song’s capital city |

| Urban structure | An enclosed Li-Fang System | An open and free Fang-Xiang system |

| Marketplaces | Dongshi and Xishi | Three integrated commercial districts; commercial net stretched all over the city |

| Recreational places | Xichang in the marketplaces and Buddhist monasteries | Wazis |

| Scenic areas | Buddhist monasteries; Qujiang Pond and Furong Park | The West Lake, Wushan and Fenghuang Shan |

| Marketplaces in the Twentieth Century | Commercial Districts after the 1980s | Functions of the Commercial Districts | Urban Heritages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Downtown Market | Wulin District | Modern service industries like business, finance, securities, among others | Named after the name of Hangzhou’s major northern gate in Ming Time, Wulin Gate, which was called Yuhang Gate in the Southern Song |

| New Market | Hubin District | Leisure, tourism and upscale shopping | Inherited Hangzhou’s prosperous downtown’s business of the early twentieth century |

| - | Wushan District | Traditional or historical culture and commerce. | A commercial and cultural area originated in the Southern Song Dynasty |

| Tongshang Market | Gongshu District | Tourism and mass consumption | Modern industrial heritage along the Grand Canal |

| Hushu Market | |||

| Jianggan Market | Jianggan District | Smart commerce and retail | An eponymous district of the early twentieth century market but had different location |

| Station Market |

| Transformation 1 | Transformation 2 | Transformation 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration | Southern Song Dynasty | From Qing through to the Republic of China | From the 1990s onwards |

| Role | The Southern Song’s capital | Top national hub of handcraft manufacturing and commerce; modern industrial and commercial city | Provincial capital of Zhejiang province; top tourist destination; Oriental City of Leisure |

| Social context | Early capitalist relation of production sprouted | Colonization, modernization | China’s reform and post-reform |

| Impetus | Commercial and civil culture | Commercial (silk production, modern industry) and leisure (tea, landscape) culture | commercial culture with leisure and heritage culture |

| Transformation | From the enclosed to open and free urban structure | The formation of modern marketplaces and the merge of natural landscape and urban area | The emerging of new commercial elements and expanding of the leisure space |

| Major commercial and recreational areas | Three commercial districts, commercial net and Wazis | Teahouses and Wushan area; six marketplaces and the West Lake | Five marketplaces, eighteen professional commercial streets, hundreds of commercial complexes; three World Heritage and the Xixi Wetland |

| Changes in urban heritages | The West Lake | The West Lake; Wushan | The West Lake; the Grand Canal; the Liangzhu Prehistoric Site |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cao, K.; Xie, W.; Zhu, J.; Wei, F. Commercial Culture as a Key Impetus in Shaping and Transforming Urban Structure: Case Study of Hangzhou, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310620

Cao K, Xie W, Zhu J, Wei F. Commercial Culture as a Key Impetus in Shaping and Transforming Urban Structure: Case Study of Hangzhou, China. Sustainability. 2023; 15(13):10620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310620

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Kang, Wenbo Xie, Jin Zhu, and Fang Wei. 2023. "Commercial Culture as a Key Impetus in Shaping and Transforming Urban Structure: Case Study of Hangzhou, China" Sustainability 15, no. 13: 10620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310620

APA StyleCao, K., Xie, W., Zhu, J., & Wei, F. (2023). Commercial Culture as a Key Impetus in Shaping and Transforming Urban Structure: Case Study of Hangzhou, China. Sustainability, 15(13), 10620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310620