Green Development Policies for China’s Manufacturing Industry: Characteristics, Evolution, and Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Intensified Environmental Pressure from the Development of Manufacturing Industry

2.1. Rapid Expansion of the Manufacturing Industry

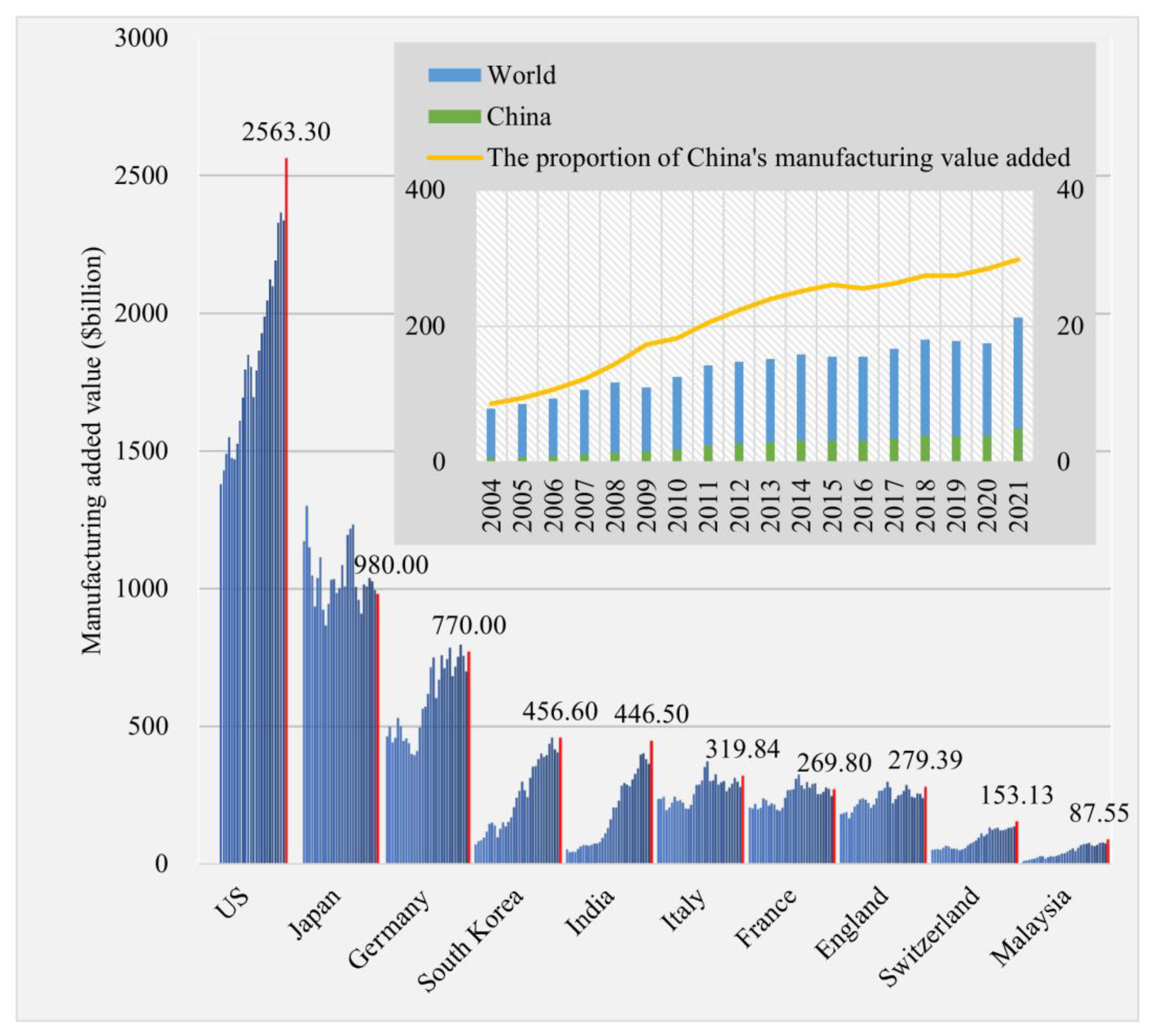

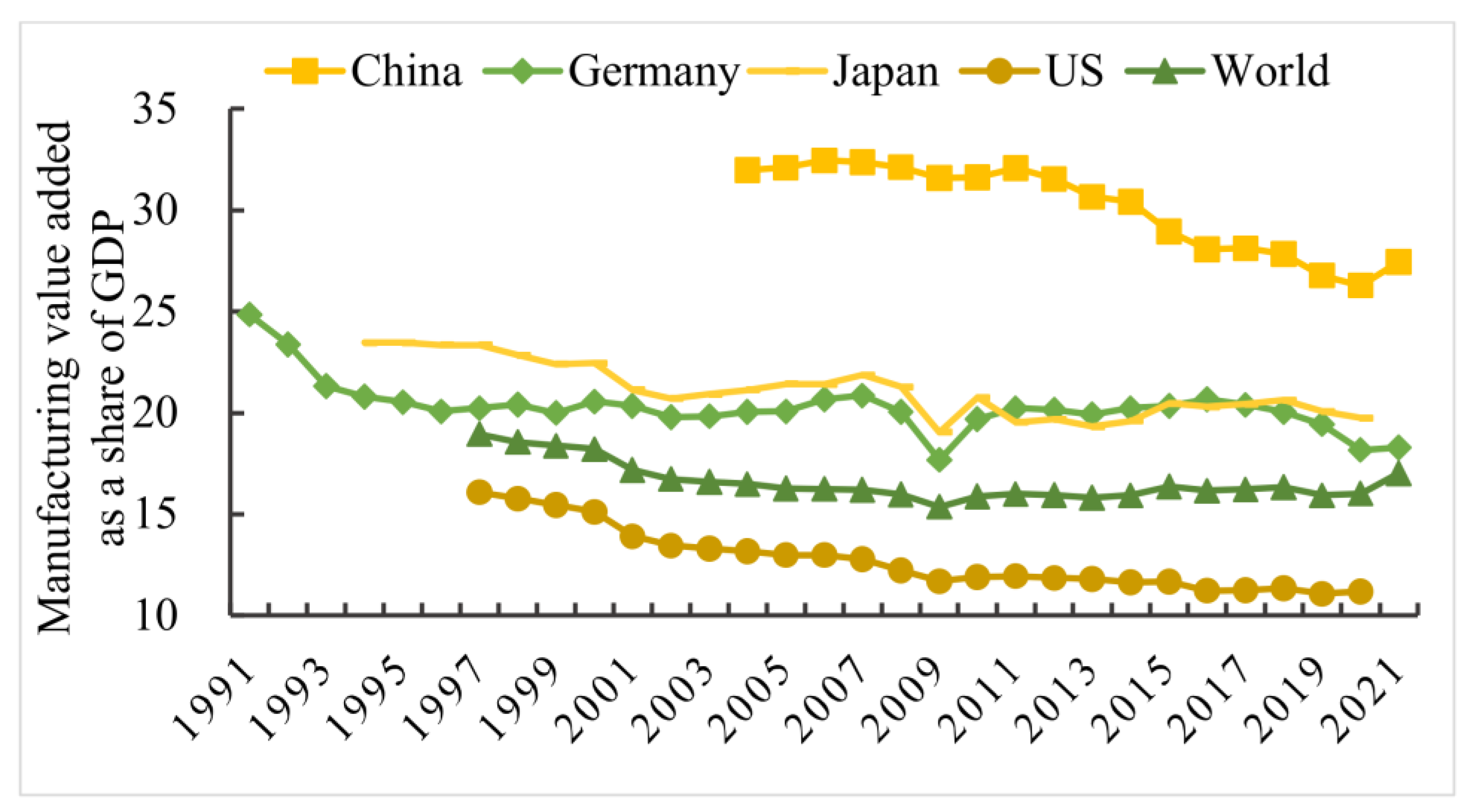

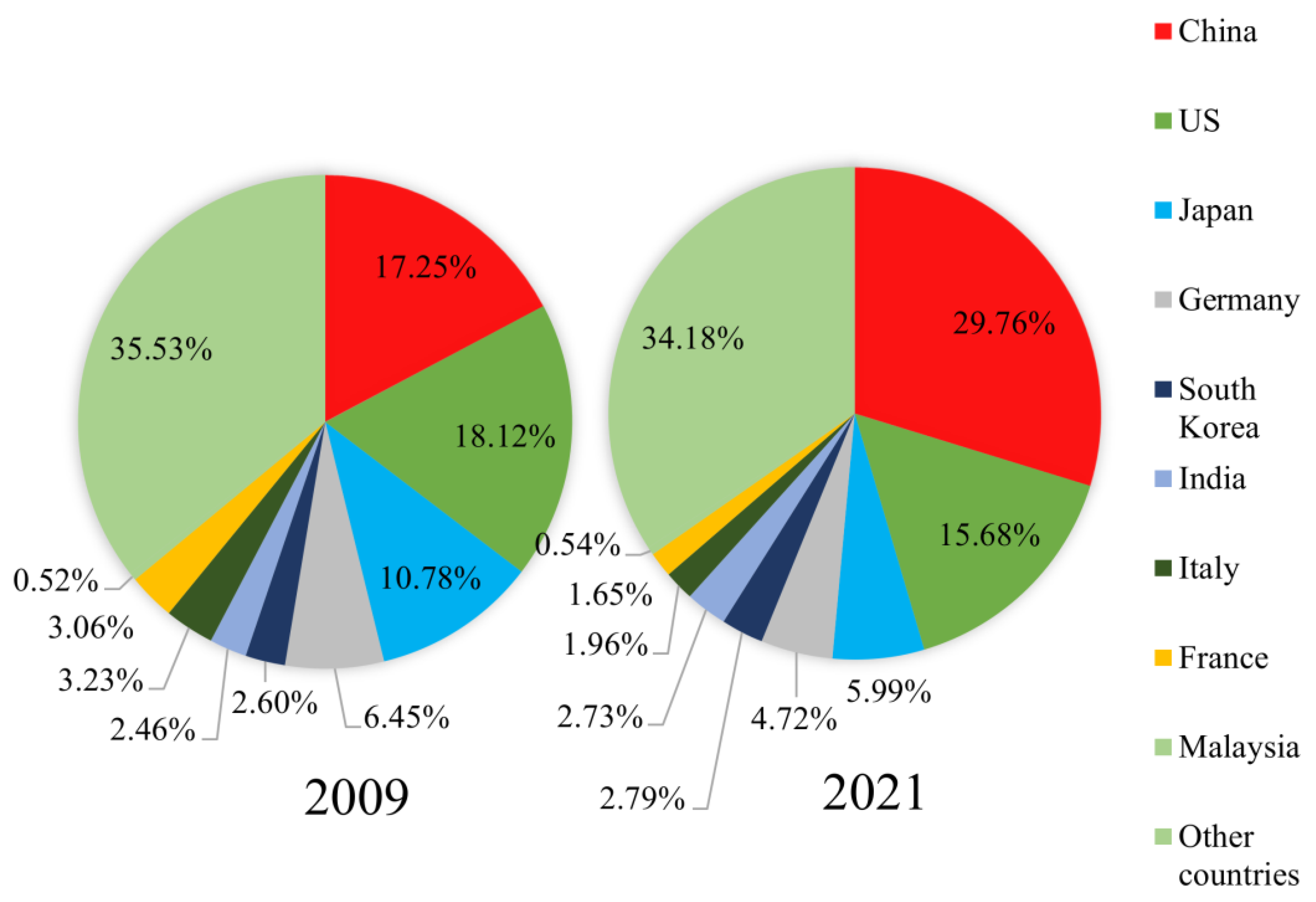

2.1.1. Growth of the Global Manufacturing Industry

2.1.2. Growth of China’s Manufacturing Industry

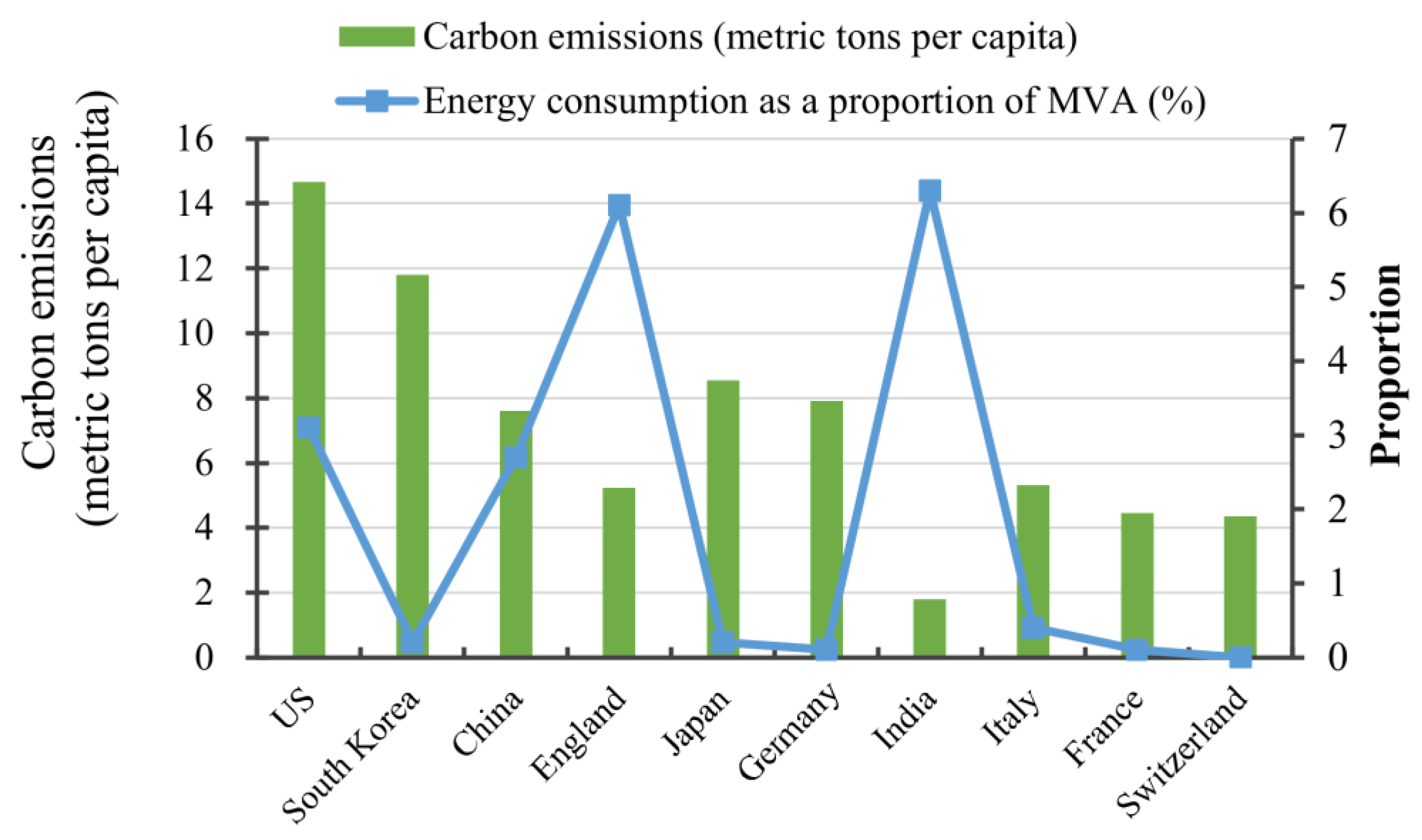

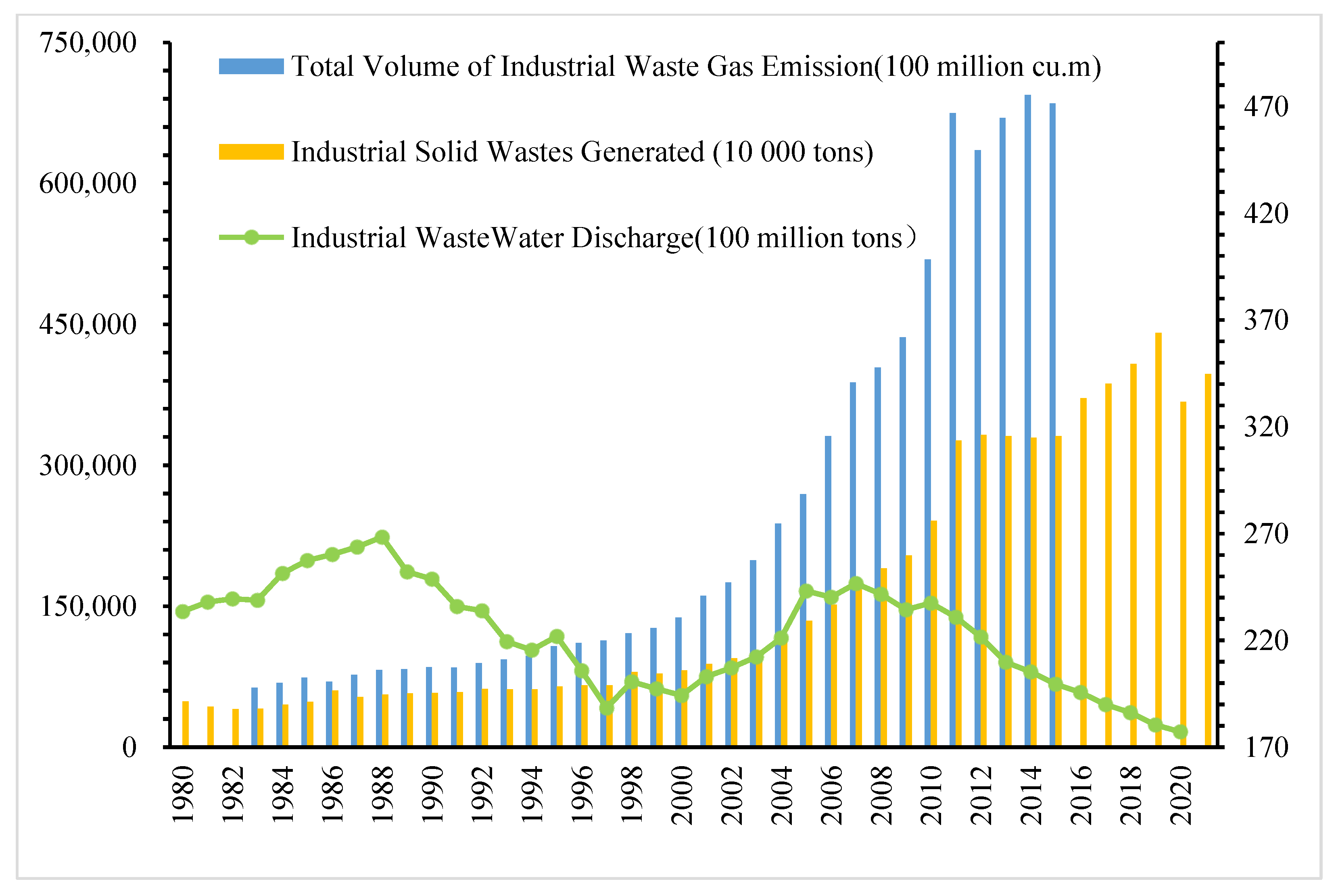

2.2. The Manufacturing Industry Is a Major Source of Pollution

2.2.1. Global Manufacturing Pollution

2.2.2. Pollution in China’s Manufacturing Industry

3. Methods and Data Sources

3.1. Methods

3.2. Data Sources

4. The Evolution of Manufacturing Policies for Green Development in China

4.1. The Exploring Period (1949–1977)

4.2. The Formal Establishment Period (1978–2001)

4.3. The Improvement and Strengthening Period (2002–2011)

4.4. The Comprehensive Improvement Period (2012 to Present)

5. Evolutionary Characteristics of China’s Green Development Policies for the Manufacturing Industry

5.1. Policy Quantities from Less to More

5.2. Policy Categories from “Government Intervention” to “Market Incentives” and “Public Participation”

5.3. Policy Concept from “Pollution Prevention and Control” to “Ecological Civilization”

6. Challenges for Green Development of China’s Manufacturing Industry

6.1. Compatibility between Economic Development and Environmental Protection Needs to Be Strengthened

6.2. Primarily Command-and-Control Based Policy Structure Needs to Be Reformed

6.3. Collaboration of Multi-Departmental Management System Needs to Be Enhanced

7. Prospects of Green Development Policy for China’s Manufacturing Industry

7.1. Aligning Environmental and Manufacturing Policies in Setting Strategic Objectives and Benchmarks

7.2. Concentrating on the Systemic Nature of Policies and the Interdependence of Policy Tools

7.3. Enhancing Processes for Policy Creation, Implementation, Monitoring, and Evaluation

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Yang, J. The asymmetric effects of economic growth, urbanization and deindustrialization on carbon emissions: Evidence from China. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asumadu-Sarkodie, S.; Owusu, P.A. Carbon dioxide emission, electricity consumption, industrialization, and economic growth nexus: The Beninese case. Energy Source Part B 2016, 11, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltrin, L.; Mah, A.; Brown, D. Noxious deindustrialization: Experiences of precarity and pollution in Scotland’s petrochemical capital. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2022, 40, 950–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Lin, B. How to promote the growth of new energy industry at different stages? Energy Policy 2018, 118, 390–403. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.; Lin, B. Can expanding natural gas consumption reduce China’s CO2 emissions? Energy Econ. 2019, 81, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Xu, B. R&D investment, carbon intensity and regional carbon dioxide emissions. J. Xiamen Univ. Arts Soc. Sci. Edn. 2020, 80, 70–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Nazzal, M.A.; Darras, B.M. Cyber-Physical Systems as an Enabler of Circular Economy to Achieve Sustainable Development Goals: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 2022, 9, 955–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharlemann, J.P.; Brock, R.C.; Balfour, N.; Brown, C.; Burgess, N.D.; Guth, M.K.; Ingram, D.J.; Lane, R.; Martin, J.G.; Wicander, S.; et al. Towards understanding interactions between sustainable development goals: The role of environment–human linkages. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 15, 1573–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warchold, A.; Pradhan, P.; Kropp, J.P. Variations in sustainable development goal interactions: Population, regional, and income disaggregation. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, P.P.; Jalal, K.F.; Boyd, J.A. An Introduction to Sustainable Development; Earthscan: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.Z. Review and Prospect of the UN Efforts for Sustainable Development. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2012, 10, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Benanav, A. Automation and the Future of Work; Verso Books: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rowthorn, R.; Ramaswamy, R. Deindustrialization: Causes and Implications; IMP Working Paper; IMF Publication: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, A. Coping with deindustrialization in the global North and South. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2022, 26, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D. The Green Development and the New Stage of Industrialization: Progress in China and Comparison with Others. China Ind. Econ. 2018, 10, 5–18. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Abdouli, M.; Hammami, S. Economic growth, FDI inflows and their impact on the environment: An empirical study for the MENA countries. Qual. Quant. 2017, 51, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J. A new look at the FDI-income-energy-environment nexus: Dynamic panel data analysis of ASEAN. Energy Policy. 2016, 91, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, G.A.; Alam, K.; Gow, J. Ecological and economic growth interdependency in the Asian economies: An empirical analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 13159–13172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, B.; Chu, C.J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.T.; Yang, S.H.; Wang, Q. Assessing the Coordinate Development between Economy and Ecological Environment in China’s 30 Provinces from 2013 to 2019. Environ. Model. Assess. 2022, 28, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peizhen, J.; Chong, P.; Malin, S. Macroeconomic uncertainty, high-level innovation, and urban green development performance in China. China Econ. Rev. 2019, 55, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.Z.; Tong, Y.L.; Zou, W. The evolution and a temporal-spatial difference analysis of green development in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 41, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.M.; Appolloni, A.; Cavallaro, F.; D’Adamo, I.; Di Vaio, A.; Ferella, F.; Gastaldi, M.; Ikram, M.; Kumar, N.M.; Martin, M.A.; et al. Development Goals towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Khan, S.; Ozturk, I.; Murshed, M. The role of renewable energy investment in tackling climate change concerns: En-vironmental policies for achieving SDG-13. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 1888–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.M.; Nguyen, L.D. The relationship between urbanization and economic growth: An empirical study on ASEAN countries. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2018, 42, 316–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Industry and China. The Added Value of China’s Manufacturing Industry Has Ranked First Worldwide for 13 Consecutive Years. 2022. Available online: https://news.cctv.com/2023/03/01/ARTIYpYprQc6CpWy2PkQHi6x230301.shtml (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5 °C. 2022. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2022/06/SR15_Full_Report_HR.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Yang, L.; Ouyang, H.; Fang, K.N.; Ye, L.L.; Zhang, J. Evaluation of regional environmental efficiencies in China based on super-efficiency-DEA. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 51, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BP. Global Energy Review. 2022. Available online: https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business~sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy~economics/statistical~review/bpstats~review~2022~full~report.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Margrit, S.; Christoph, S.; Markus, J.; Thomas, D.; Amanda, W. Qualitative Content Analysis: Conceptualizations and Challenges in Research Practice—Introduction to the FQS Special Issue “Qualitative Content Analysis I”. Forum Qual. Soz. 2019, 20, 38. [Google Scholar]

- The National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. Common Program of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. 1949. Available online: http://www.cppcc.gov.cn/2011/12/16/ARTI1513309181327976.shtml (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- The National Construction Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Interim Health Standards for Industrial Enterprise Design. People’s Health Publishing House, Beijing. 1956. Available online: http://47.108.163.154/GBZ12010%E5%B7%A5%E4%B8%9A%E4%BC%81%E4%B8%9A%E8%AE%BE%E8%AE%A1%E5%8D%AB%E7%94%9F%E6%A0%87%E5%87%86.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- The Eighth Central Committee of the Communist Party of China at the Tenth Meeting. Communiqué of the Tenth Plenary Session of the Eighth Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. 1962. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/test/2008-06/05/content_1006834.htm (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- The Eleventh Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. Communiqué of the Third Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. 1978. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/test/2009-10/13/content_1437683.htm (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Chen, S.Y. Energy Consumption, CO2 Emission and Sustainable Development in Chinese Industry. Econ. Res. J. 2009, 44, 41–55. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- The Sixth National People’s Congress at Its Fourth Meeting. The 7th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China. 1986. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/fggz/fzzlgh/gjfzgh/200709/P020191029595676468654.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- The Standing Committee of the Seventh National People’s Congress at Its Eleventh Meeting. Environmental Law of the People’s Republic of China. 1989. Available online: https://www.audit.gov.cn/oldweb/n8/n28/c10241260/part/10241580.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- The State Council. Decision of the State Council on Further Strengthening Environmental Protection. 1990. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/zcwj/gwywj/201811/t20181129_676353.shtml (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- The Ninth National People’s Congress at Its Fourth Meeting. Outline of the 10th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China. 2001. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2001/content_60699.htm (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Chen, Y.W. The policy and practice innovation of low-carbon economy in Western countries and its enlightenment to China. Inq. Into Econ. Issues 2010, 8, 1–7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- The Standing Committee of the Ninth National People’s Congress at Its Twenty-Eighth Meeting. Cleaner Production Improvement Law. 2002. Available online: https://gkml.samr.gov.cn/nsjg/bgt/202211/t20221103_351318.html (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Jiang, Z.M. Report of the 16th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. 2002. Available online: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/kpchinese.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- The State Council. Interim Provisions on Promoting Industrial Structure Adjustment. 2005. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2005-12/21/content_133214.htm (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- The Eleventh National People’s Congress at Its Fourth Meeting. Outline of the 12th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development. 2011. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/2011lh/content_1825838.htm (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Hu, J.T. Report of the 16th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. 2012. Available online: http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2012/1118/c64094-19612151.html (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- The Standing Committee of the Twelfth National People’s Congress at Its Eighth Meeting. The New Environmental Protection Law. 2014. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/fgbz/fl/201404/t20140425_271040.shtml (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- The State Council. Made in China 2025. 2015. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-05/19/content_9784.htm (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. Industrial Green Development Plan (2016–2020). 2016. Available online: http://www.scio.gov.cn/xwfbh/xwbfbh/wqfbh/33978/34888/xgzc34894/Docume (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- The Standing Committee of the Twelfth National People’s Congress at Its Twenty-Fifth Meeting. Environmental Protection Tax Law. 2016. Available online: http://www.chinatax.gov.cn/chinatax/n610/c5178958/content.html (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- The State Council. Environmental Protection Tax Law Implementation Regulations. 2017. Available online: http://www.chinatax.gov.cn/n810341/n810755/c3002759/content.html (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Xi, J.P. Report of the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. 2022. Available online: https://www.chinacourt.org/article/detail/2022/10/id/6975843.shtml (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Zhang, X.Y.; Liu, J.J. The Evolution and Orientation Choice of Environmental Regulation Policy in PRC from 1949 to 2019. Reform 2009, 10, 16–25. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Juan, L. Review on the Construction of Ecological Civilization System in China Since Reform and Opening up. Soc. Sci. Chin. High. Educ. Inst. 2019, 2, 33–42. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=QhvK1uXUvSM6ChjSPg20g0JD9LIcBTBqZ4vvDnNfJpUe56kngBBK2s-zscw41FN9McTH9y0Bs9BohLNeIfgkN0NSW4vXCneEceO9MB0xLiCPkUSUm6vtuADxh0DBOkWt_ES2roWILhg=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 12 May 2023). (In Chinese).

- Lütkenhorst, W.; Altenburg, T.; Pegels, A.; Vidican, G. Green Industrial Policy: Managing Transformation under Uncertainty; Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik Discussion Paper; IDOS: Bonn, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.P.; Zhang, Y.J.; Jiang, F.T. Green Industrial Policy: Theory Evolution and Chinese Practice. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 45, 4–27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, X.R.; Chen, L.P.; Yuan, X.L.; Tang, Y.Z.; Yuan, Q.; Chen, R.; Wang, Q.S.; Ma, Q.; Zuo, J.; Liu, H.W. Green supply chain management for a more sustainable manufacturing industry in China: A critical review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 1151–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, J. Industrial Policy for a Green Economy; International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Borrás, S.; Edquist, C. The choice of innovation policy instruments. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2013, 80, 1513–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, D. Green industrial policy. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2014, 30, 469–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, A.; Rodrik, D. Green Industrial Policy: Accelerating Structural Change towards Wealthy Green Economies; Green Industrial Policy; IDOS: Bonn, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stéphane, H.; Fay, M.; Vogt-Schilb, A. Green Industrial Policies: When and How; World Bank Policy Research Working; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- DRC. Industrial Upgrading for Green Growth in China: Thematic Focus on Environment: Key Findings and Recommendations; Development Research Centre of the State Council of China, DRC: Beijing, China, 2017.

| Year | Representative Policies | Main Potent |

|---|---|---|

| 1949 | Common Program of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference [30] | Focus should be placed on the systematic restoration and development of heavy industries in order to create the foundation for national industrialization. In addition, people’s standard of living should be restored and expanded in order to meet their daily consumption needs. |

| 1956 | Interim Health Standards for Industrial Enterprise Design [31] | The policy is comprehensively to address the health and safety problems of industrial enterprises. |

| 1962 | Communiqué of the Tenth Plenary Session of the Eighth Central Committee of the Communist Party of China [32] | Agriculture should be the foundation, and industry the mainstay. |

| Year | Representative Policies | Main Potent |

|---|---|---|

| 1978 | Communiqué of the Third Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee of the Communist Party of China [33] | It was decided to shift the focus of the Party and the state’s work to economic construction and to initiate reform and opening up. |

| 1986 | Seventh Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China [35] | The need to accelerate energy development and conservation and vigorously strengthen the development of electrical equipment, mining equipment, and petroleum equipment in response to the bottleneck of coal, electricity, oil, transportation, materials, and other resources. |

| 1989 | The Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China [36] | Priority procurement and use of environmentally friendly products, equipment, and facilities and the new five systems for strengthening environmental management. |

| 1990 | Decision of the State Council on Further Strengthening Environmental Protection [37] | To formulate eight systems of environmental protection which included the addition of the environmental impact assessment system, the “three simultaneous” system, and the sewage charging system to the original five systems. |

| 2001 | Outline of the Tenth Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China [38] | To study and formulate policies and measures to revitalize the equipment manufacturing industry, develop competitive manufacturing and high-tech industries, and energetically promote service industries. |

| Year | Representative Policies | Main Potent |

|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Cleaner Production Improvement Law [40] | Pollution control mode begins to change from end treatment to whole process control. |

| 2002 | Report of the 16th National Congress of the Communist Party of China [41] | Taking a new type of industrialization road with high technological content, good economic efficiency, low resource consumption, and less environmental pollution, and the advantages of human resources are given full play. |

| 2005 | Interim Provisions on Promoting Industrial Structure Adjustment [42] | Promoting the optimization and upgrading of industrial structure and the healthy and coordinated development of the primary, secondary, and tertiary industries. |

| 2011 | Outline of the 12th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development [43] | Vigorously cultivate and develop strategic emerging industries. |

| Year | Representative Policies | Main Potent |

|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Report of the 16th National Congress of the Communist Party of China [44] | Emphasizing that tighter standards for the path of the manufacturing industry’s development should be proposed from the peak of ecological civilization construction, together with a more comprehensive theoretical system and policy actions. |

| 2014 | The New Environmental Protection Law [45] | The responsibility of the government and enterprises for environmental governance has been strengthened, and penalties for environmental violations have been greatly strengthened. |

| 2015 | Made in China 2025 [46] | In accordance with the “innovation-driven, quality first, green development, structural optimization, talent-oriented” basic policy to promote the development of manufacturing. |

| 2016 | Industrial Green Development Plan (2016–2020) [47] | Promoting green development of manufacturing industry. |

| 2016 | Environmental Protection Tax Law [48] | First separate tax law to embody a “green tax system”. |

| 2017 | Environmental Protection Tax Law Implementation [49] | Environmental protection “fee to tax” officially completed. |

| 2022 | Report of the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China [50] | Promoting the high-end, intelligent and green development of the manufacturing industry. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, W.; Xu, L.; Wu, S.; Xu, Y.; Han, S. Green Development Policies for China’s Manufacturing Industry: Characteristics, Evolution, and Challenges. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310618

Jin W, Xu L, Wu S, Xu Y, Han S. Green Development Policies for China’s Manufacturing Industry: Characteristics, Evolution, and Challenges. Sustainability. 2023; 15(13):10618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310618

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Weibo, Lijie Xu, Shiping Wu, Yao Xu, and Shiwen Han. 2023. "Green Development Policies for China’s Manufacturing Industry: Characteristics, Evolution, and Challenges" Sustainability 15, no. 13: 10618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310618

APA StyleJin, W., Xu, L., Wu, S., Xu, Y., & Han, S. (2023). Green Development Policies for China’s Manufacturing Industry: Characteristics, Evolution, and Challenges. Sustainability, 15(13), 10618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310618