Promoting Urban Health through the Green Building Movement in Vietnam: An Intersectoral Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

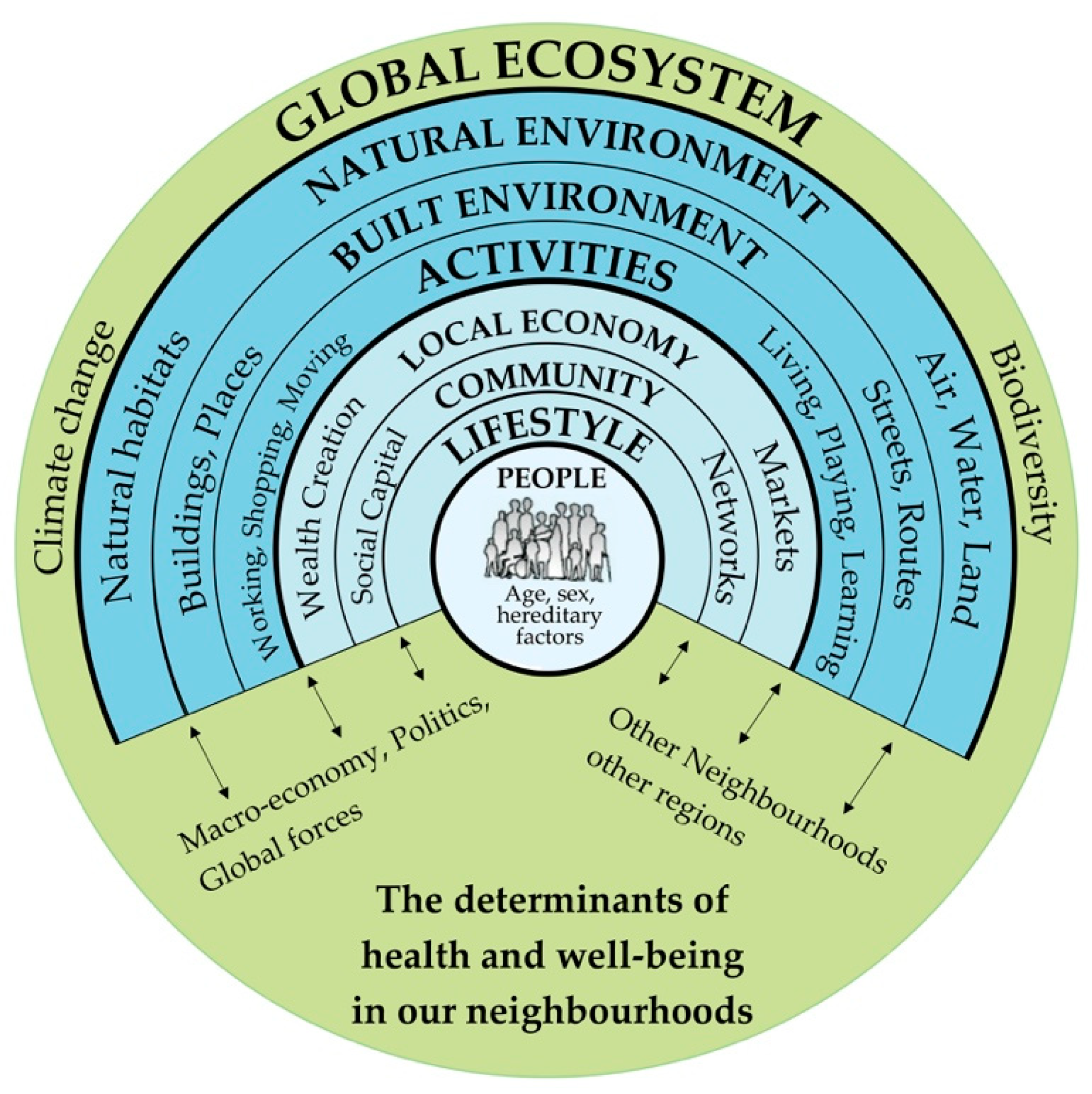

2. Literature Overview

3. Methodology

4. Results

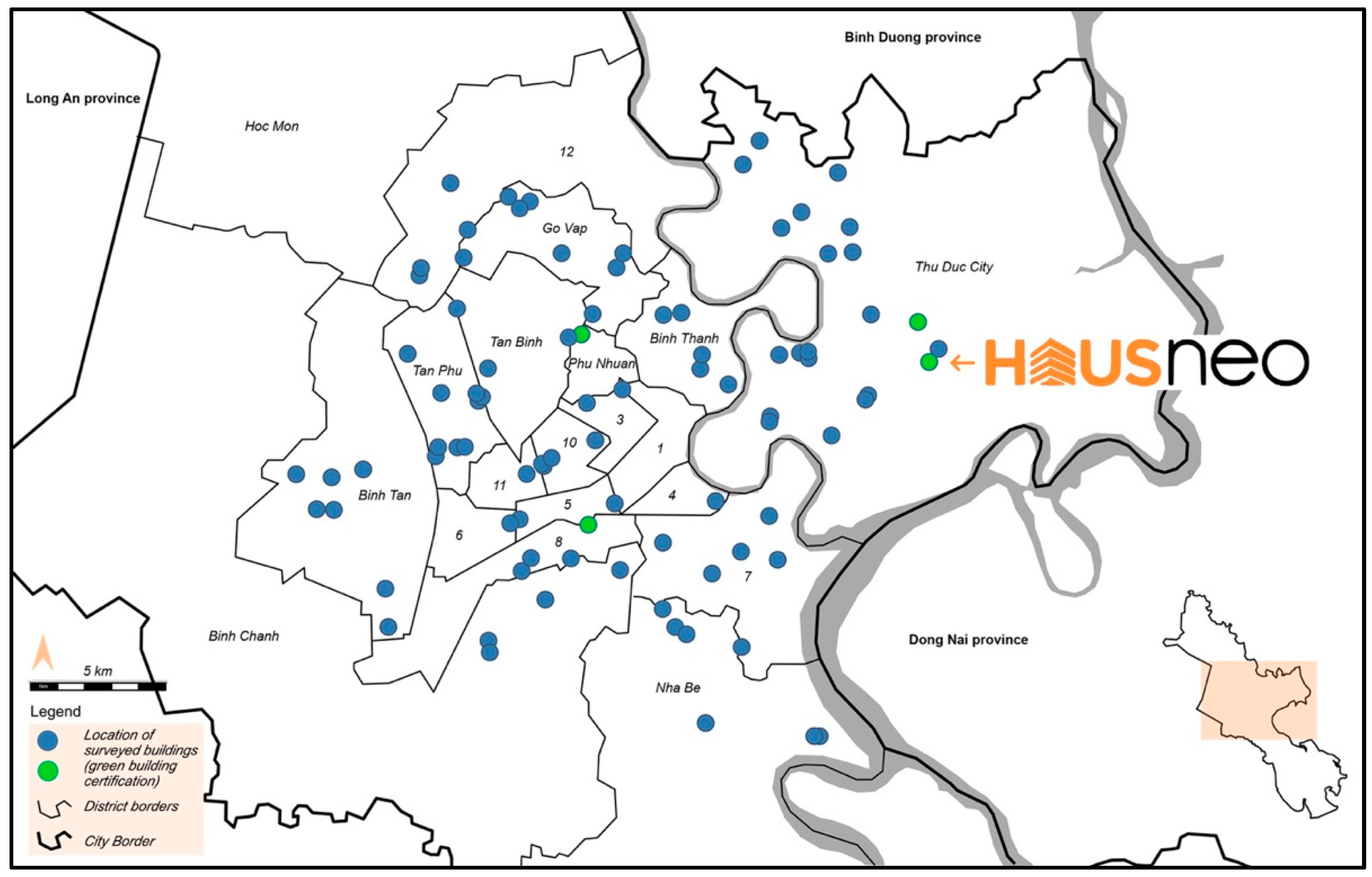

4.1. Introduction to HausNeo Building Characteristics

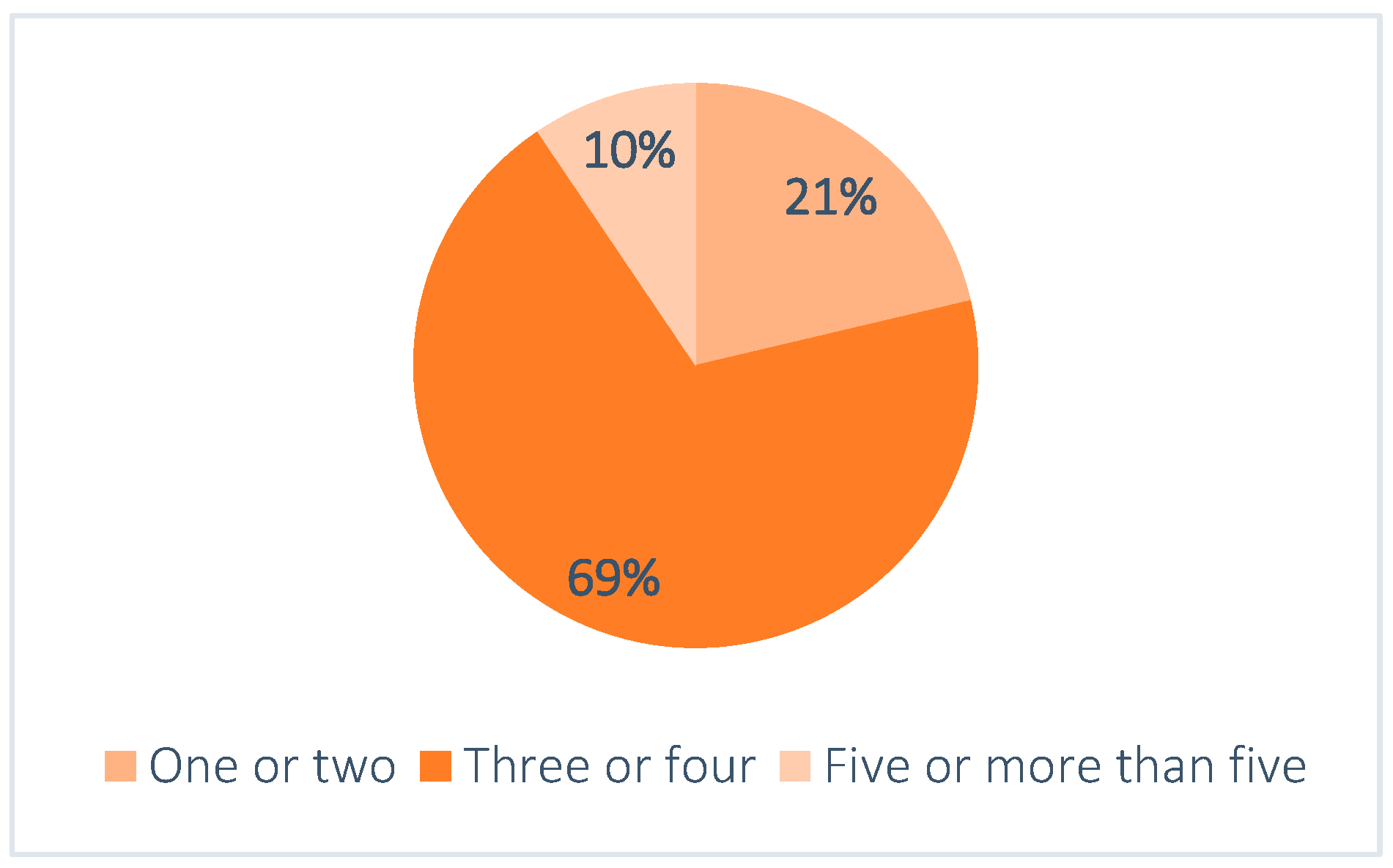

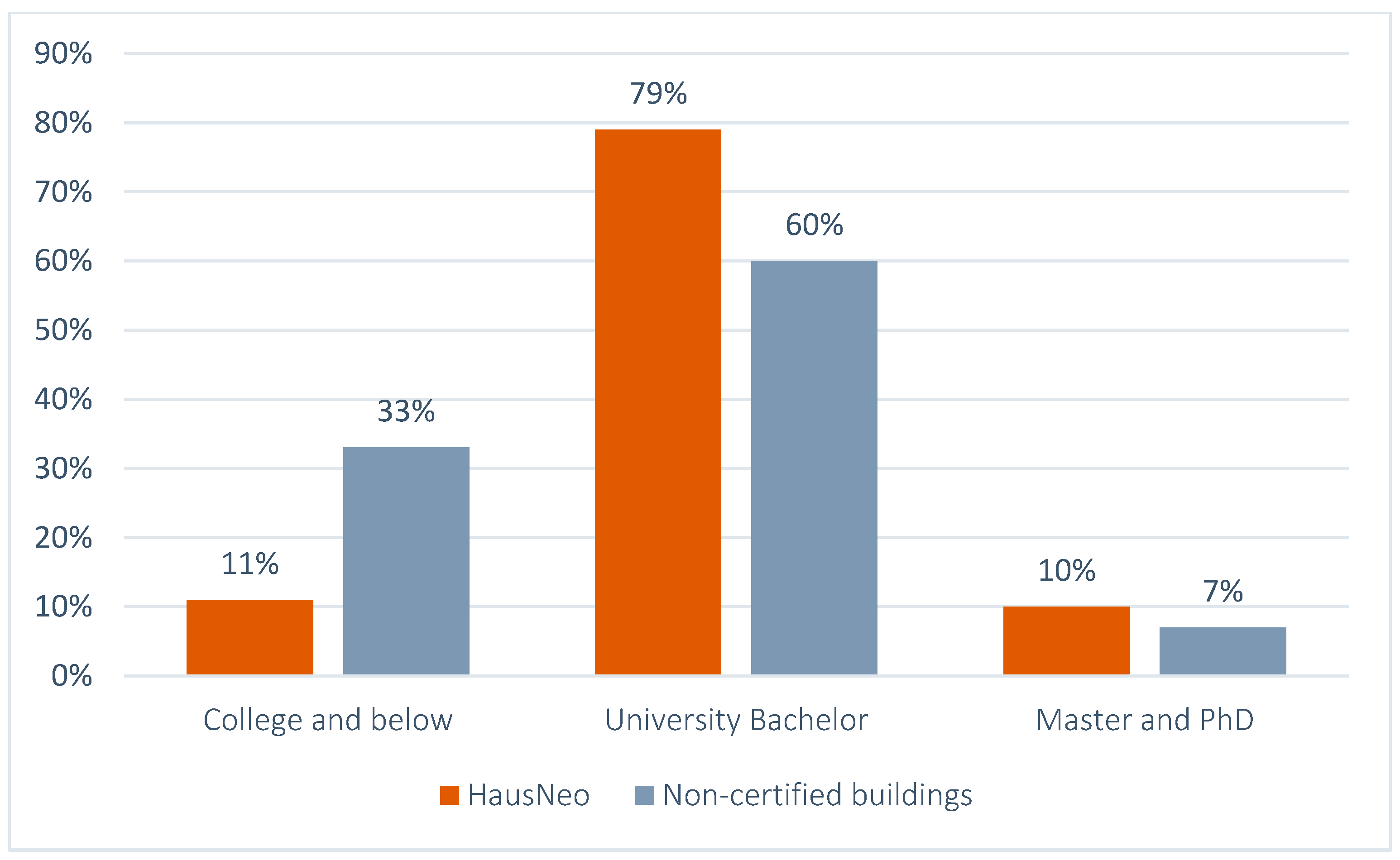

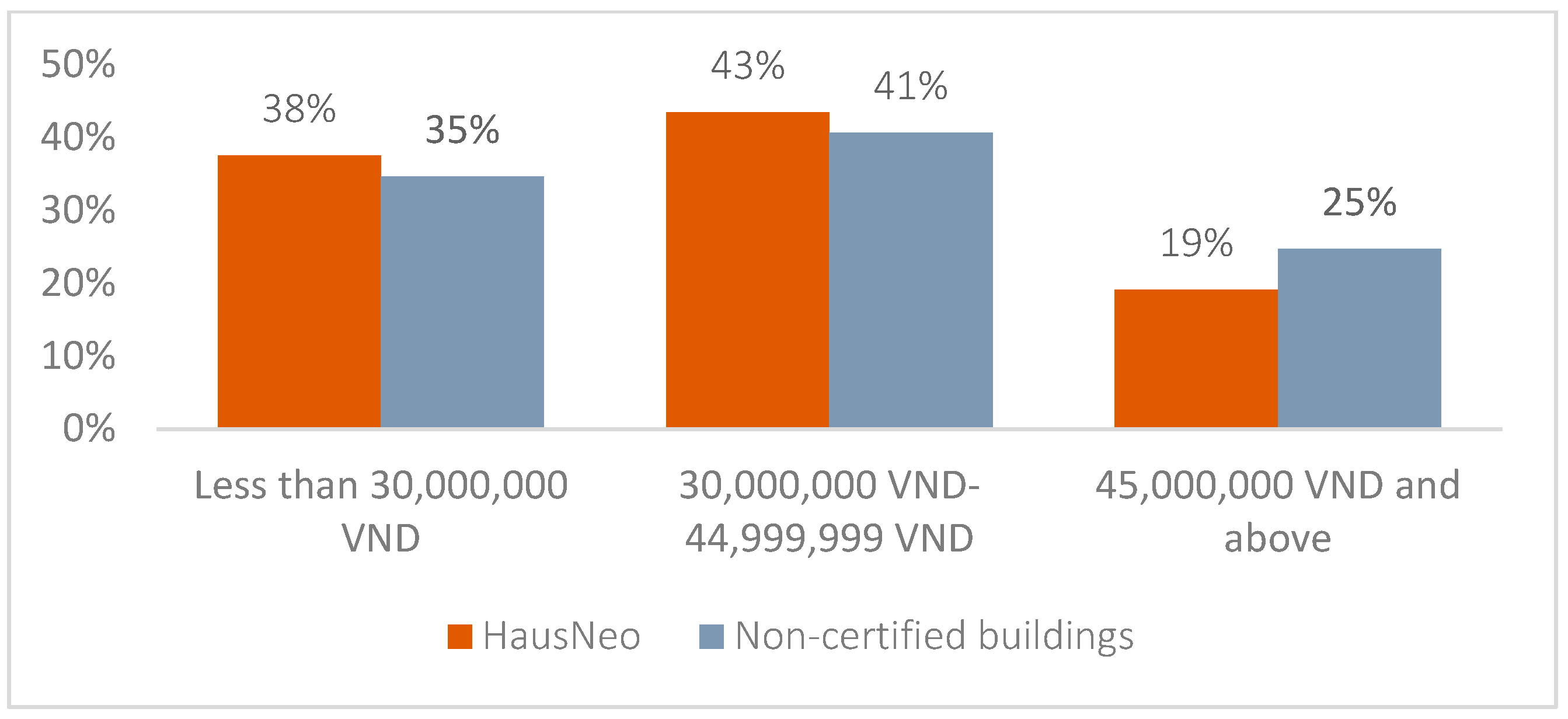

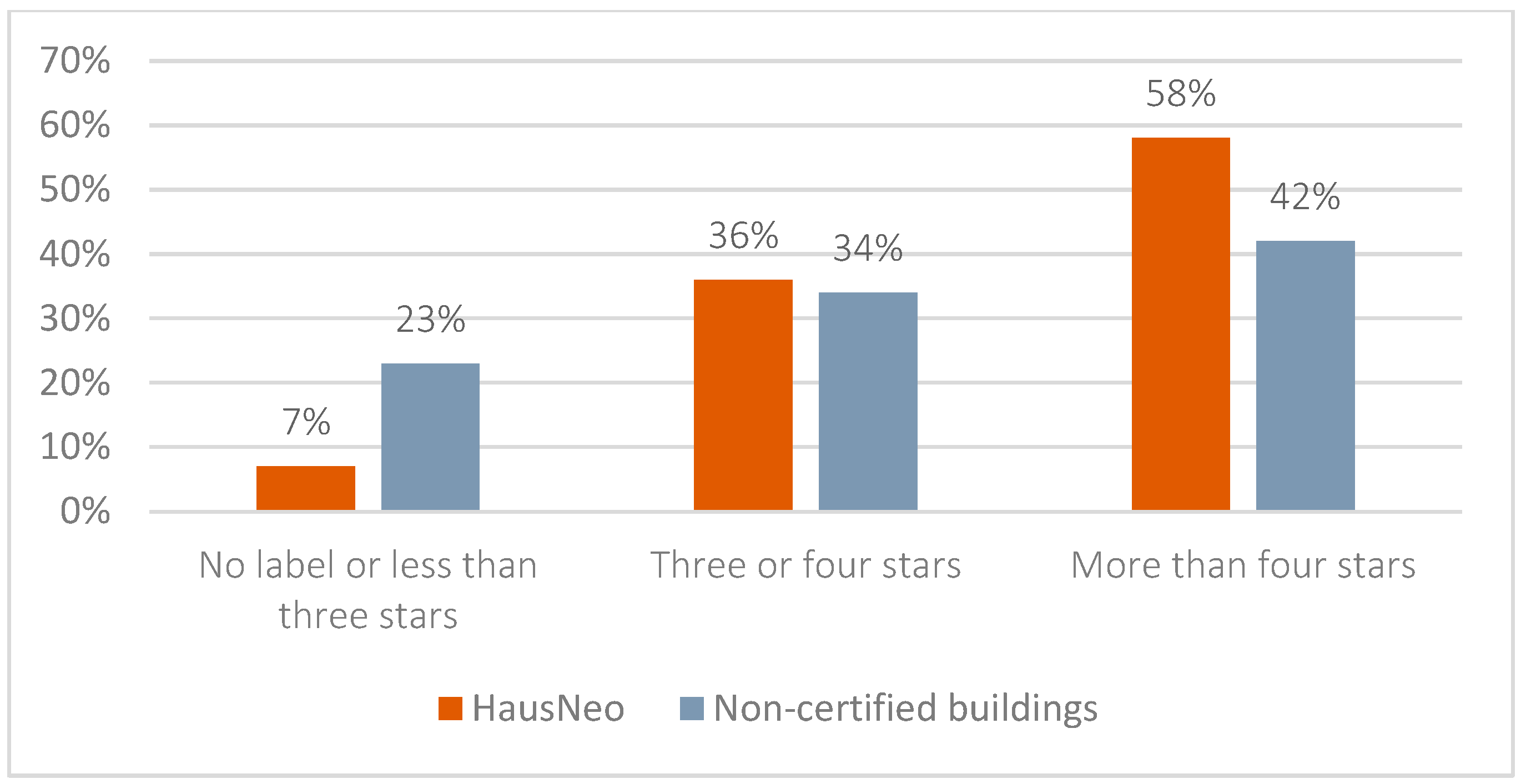

4.2. Households’ Socio-Economic Conditions

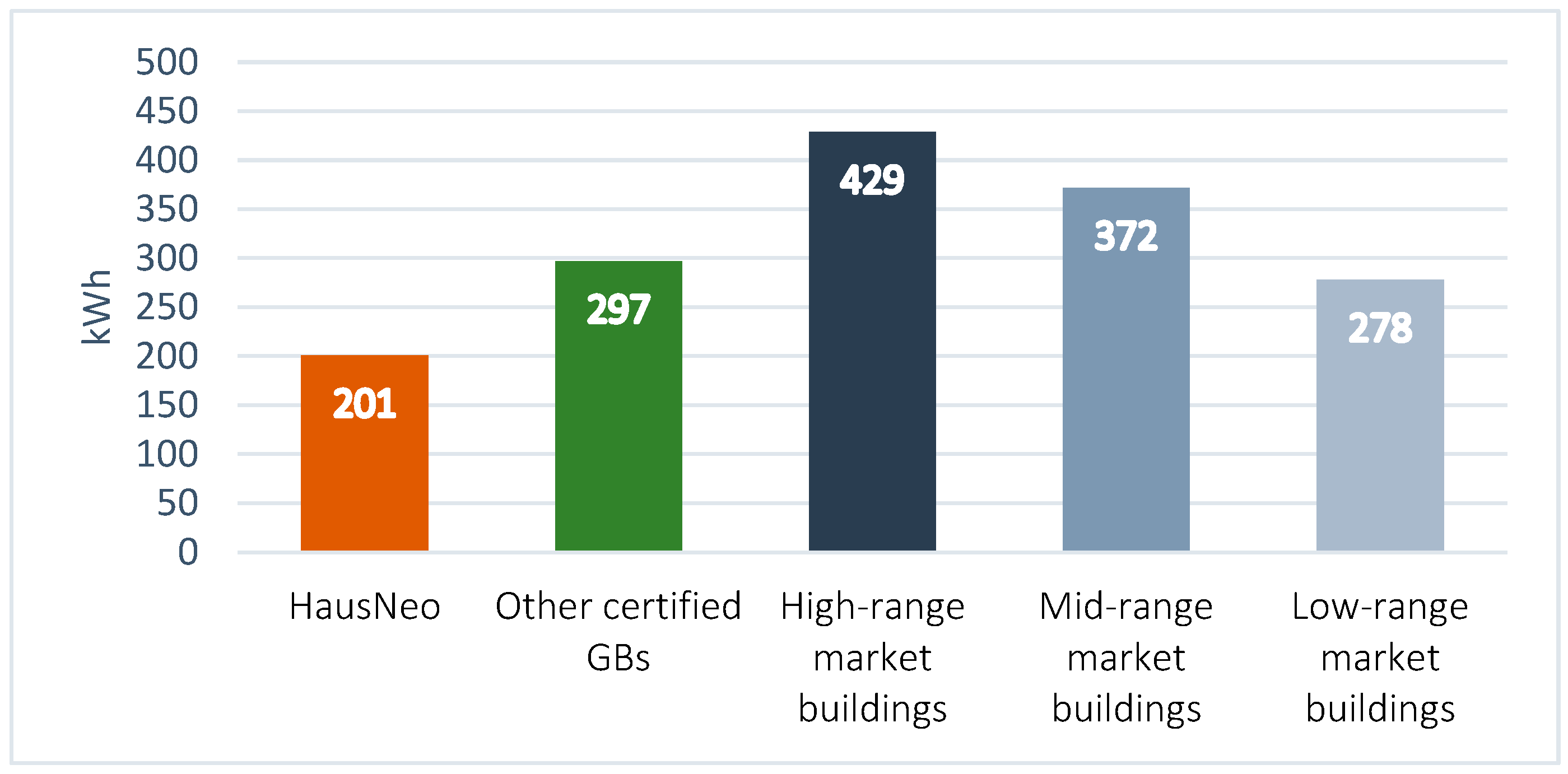

4.3. Power Consumption

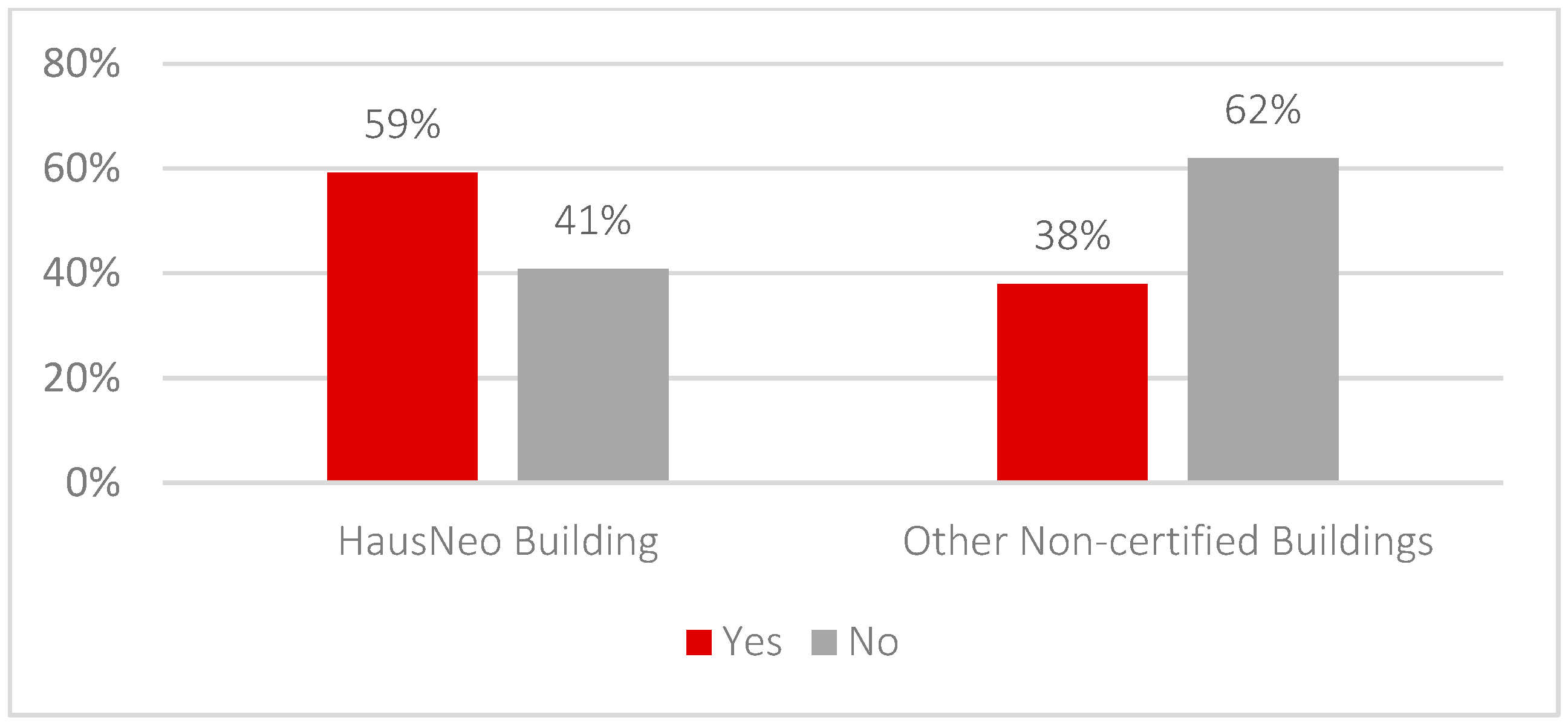

4.4. Knowledge about Green Building Certification

4.5. Factors Influencing Homebuyers’ Decisions

4.6. Sustainable Building Features

4.7. Apartment Price Per Sqm and Energy-Saving Technical Features

4.8. Other Homebuying Influencing Factors

4.9. Households’ Concerns

4.10. Experts’ Opinions on Health Co-Benefits of Green Buildings

5. Discussion

5.1. Green Buildings’ Low Energy Consumption and The Potential to Improve Users’ Health

5.2. High Attention to Green Building Features Versus Low Awareness about Green Building Certification

5.3. Health Concern Versus Low Priority for Apartment Price and Energy Savings

5.4. The Need for Consideration of Health Co-Benefits in Vietnamese GBM

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Order | Webinar Title | Date | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Presentation on primary research analysis results with the Developer Company of HausNeo, EZ Land, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam | 5 April 2021 | W1 |

| 2 | Challenges and Opportunities of Green Building Movement in Vietnam, collaboration with Green Sector Business Committee of European Chamber of Commerce, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam | 6 September 2021 | W2 |

| 3 | Challenges and Opportunities of promoting green buildings in the coastal areas of Central Vietnam, collaboration with Central University of Civil Engineering (MUCE), Tuy Hoa, Vietnam | 16 December 2021 | W3 |

| 4 | HOPE 1: Policies and Practices to engage with building users in creating well-being and sustainable living environment in Vietnamese cities, collaboration with the Competence Center for Sustainable Buildings in Vietnam (CCSB-VN) and Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Hanoi, Vietnam | 20 April 2022 | W4 |

| 5 | HOPE 2: Health Governance to promote inclusive urban planning approaches targeting the quality of life for citizens in Vietnam collaboration with the Competence Center for Sustainable Buildings in Vietnam (CCSB-VN) and Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Hanoi, Vietnam | 30 June 2022 | W5 |

| 6 | HOPE 3: Green building design and sustainable neighborhood development towards public health in the built environment of Vietnam collaboration with the Competence Center for Sustainable Buildings in Vietnam (CCSB-VN) and Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Hanoi, Vietnam | 18 August 2022 | W6 |

| 7 | HOPE 4: Health governance to promote comprehensive life cycle assessment of materials in regard of sustainable construction in Vietnam collaboration with the Competence Center for Sustainable Buildings in Vietnam (CCSB-VN) and Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Hanoi, Vietnam | 28 September 2022 | W7 |

| Order | Experts’ Anonym and Position | Date | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dr. A, Lecturer at Hanoi University of Civil Engineering | 15 November 2021 | E1 |

| 2 | Assoc. Prof. B, Lecturer at Hanoi University of Civil Engineering | 5 June 2021 | E2 |

| 3 | MA. C, Engineer, Construction Company, Vietnam | 2 July 2021 | E3 |

| 4 | Mr. D, Engineer, Landscape Design Company, Vietnam | 20 January 2022 | E4 |

| 5 | Mr. E, Architect, Green Building Consultant, Vietnam | 18 March 2022 | E5 |

| 6 | Mr. F, Architect, Architectural Design Studio, Vietnam | 25 March 2022 | E6 |

| 7 | Mr. G, Green Building Developer, Vietnam | 07 May 2021 | E7 |

| 8 | Mr. H, Green Building Development, Vietnam | 24 May 2022 | E8 |

| 9 | Dr. I, Economist, Green Building Developer, Vietnam | 08 November 2021 | E9 |

| 10 | Ms. J, Engineer, Green Building Certifying Organization, Vietnam | 31 May 2022 | E10 |

| 11 | Mr. K, Engineer, Green Building Certifying Organization, Vietnam | 05 June 2022 | E11 |

Appendix B

| 1 | INTERVIEW DATE AND CONTACT |

| This section helps (1) to identify the interviewer for eventual check-backs and (2) to link the questionnaire to the building fact sheet. | |

| 1.1 | date of interview (dd/mm/yyyy) |

| 1.2 | Name of the interviewee |

| If interviewee is under 18 years, ask another person in the household; if there is none, end the interview. | |

| 1.3 | Phone number of interviewee (optional) |

| 2 | INFORMATION ABOUT THE BUILDING |

| 2.1 | Name and address of the building |

| 2.2 | Name of investor/developer |

| 2.3 | Date of opening after completion of construction in month and year |

| 2.4 | Type of buildings (Single HRB of multi-purposes/complexed urban center/KĐTM |

| 2.5 | Geographical condition (city core center/city sub-core center/newly developed peripheral area) |

| 2.6 | Average price range per m2 |

| 2.7 | Total number of floors (excluding basements), apartments, construction density |

| 2.8 | Select the type of green certification, the building has: |

| 2.9 | Do the building have any solution to increase EE/reduce energy consumption (e.g., window materials/window-wall ratio/shading solution/renewable energy generation |

| 2.10 | Does the building have any distinguished facilities, compared with other HRB |

| 3 | INFORMATION ABOUT THE APARTMENT |

| 3.1 | Room number |

| 3.2 | Floor |

| 3.3 | Size |

| 3.4 | Orientation |

| 3.5 | Energy Efficiency Solutions (Window material, Window-to-wall ratio, etc.) |

| 4 | INFORMATION ABOUT THE INTERVIEWEE |

| 4.1 | Gender: |

| male/female/other | |

| 4.2 | What is your age? |

| If interviewee is under 18 years, ask another person in the household; if there is none, end the interview. | |

| 4.3 | Are you a decision maker in your household? e.g. you know details about the spending of the household and the maintenance of the apartment. |

| If not, ask for another person in the household; if there is none, end the interview. | |

| 5 | HOUSEHOLD PROFILE |

| We would like to know more about the comfort in your apartment and your satisfaction with it. But before, we would like to ask you some general questions about your household situation and apartment. | |

| 5.1 | How many people live in your apartment permanently, you included? Mark the number of adults and children. |

| Adults | |

| 1/2/3/4/5 | |

| Individuals below the age of 18 years | |

| 0/1/2/3/4/5 | |

| 5.2 | What is your household’s monthly income (total in VND)? Of course, you can refuse to give this information. |

| below 5,500,000/5,500,000–6,499,999/6,500,000–7,499,999/7,500,000–8,499,999/8,500,000–9,499,999/9,500,000–10,499,999/10,500,000–11,499,999/11,500,000–12,499,999/12,500,000–13,499,999/13,500,000–14,999,999/15,000,000–29,999,999/30,000,000–44,999,999/45,000,000–74,999,999/75,000,000–149,999,999/150,000,000 and higher | |

| Tick, if interviewee refuses to answer this question | |

| 5.3 | What is the highest educational level within your household? |

| less than high school/high school/college/university Bachelor/university Master & PhD | |

| 5.4 | Did someone in your household got education abroad? |

| Master abroad | |

| PhD abroad | |

| 5.5. | How many cars and/or motorcycles does your household own? 0 means, your household does not own cars/motorcycles. |

| cars | |

| motorcycles | |

| 5.6 | Do you own and rent out real estate? |

| 5.7 | How much do you pay for the building management fee per month (without parking) in VND? |

| 5.8 | Could you please provide us the power consumption records of the year 2019 and 2020. (The data can be accessed via evnhanoi.com.vn with your household’s customer number and password) |

| Tick, if interviewee refuses to give the information | |

| After giving information about your household’s energy consumption, would you tell us about the high-energy domestic appliances your household owns? | |

| 5.9 | How many of these items owns your household? 0 means, you don’t own the article. |

| e-car | |

| e-bike | |

| microwave | |

| TV | |

| fridge | |

| baking oven | |

| washing machine (with and without drying option) | |

| water heater (privately owned) | |

| A/C | |

| 6 | HOUSEHOLDS’ HABITS/BEHAVIOUR AND ATTITUDE |

| We are interested in your satisfaction with the temperature, humidity and general air quality with your apartment. Before we ask you about that, we would like to understand better, what kind of climate regulation you use and how. | |

| 6.1 | What is the type of cooling system that you use in your apartment? Select one of the options given below. |

| completely air-conditioned apartment/mixed: partly air-conditioned, partly with fans and natural ventilation/mechanical ventilation (fans, movable or ceiling)/completely naturally ventilated (windows) in all rooms/I am not sure | |

| 6.2 | When you buy electric appliances, how important are price, brand, and energy label for your decision? Please rate with very important, important, so-so, less important, not important. |

| How important is the price of electric appliances, e.g., air-conditioner, fridge, or water boiler, for you? | |

| very important/important/so-so/less important/not important | |

| How important is the brand of electric appliances, e.g., air-conditioner, fridge, for you? | |

| very important/important/so-so/less important/not important | |

| How important is the energy star label of electric appliances, e.g., air-conditioner, fridge, for you? | |

| very important/important/so-so/less important/not important | |

| 6.3 | Now, we would like to know more about the energy-efficiency of your A/C. |

| Have you bought the A/Cs in your apartment yourself? | |

| How many energy stars have your A/Cs? If you own more than one A/C with several energy star ratings, please select the energy star rating with the lowest rating. | |

| no certificate/1 star/2 stars/3 stars/4 stars/5 stars | |

| What is the brand of your A/C? | |

| We would like to know more about how exactly you use the A/Cs in the living room and your sleeping room. We will ask you about how you use them in springtime, in summer, in autumn and in winter. Please have a look with me at the matrix (matrix 2) | |

| 6.4 | How do your household use the A/Cs in the sleeping room (when, mode, temperature setting and temperature change) |

| 6.5 | How much do you agree to the following statements? Please rate with I strongly agree/I somewhat agree/so-so/I somewhat disagree/I strongly disagree. |

| Whenever possible, I turn off the A/C and switch to window and electric fan. | |

| I strongly agree/I somewhat agree/so-so/I somewhat disagree/I strongly disagree | |

| In the hot season, I let the A/C run the whole night in the sleeping room. | |

| I strongly agree/I somewhat agree/so-so/I somewhat disagree/I strongly disagree | |

| I use an A/C temperature and A/C mode that helps me to save energy costs. | |

| I strongly agree/I somewhat agree/so-so/I somewhat disagree/I strongly disagree | |

| I turn off the A/C after a while, because the climate gets uncomfortable, e.g., too cold, or too dry. | |

| I strongly agree/I somewhat agree/so-so/I somewhat disagree/I strongly disagree | |

| I keep the windows closed, because the high noise level outside disturbs me. | |

| I strongly agree/I somewhat agree/so-so/I somewhat disagree/I strongly disagree | |

| I keep the windows closed to protect my home from dust and outdoor pollution. | |

| I strongly agree/I somewhat agree/so-so/I somewhat disagree/I strongly disagree | |

| 6.6 | When you decided to buy the apartment, how important were the following factors for your decision? Rate with very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/unimportant |

| the services offered within the building (swimming pool, shops, playground, gym, etc.) | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/unimportant | |

| apartment is on the “cooler”, sun- and weather-protected side of the building | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/unimportant | |

| the location of the building, e.g., proximity to workplace, family members, schools | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/unimportant | |

| good price/sq. m of the apartment | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/unimportant | |

| Bright rooms and big windows | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/unimportant | |

| Good natural ventilation of the rooms | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/unimportant | |

| Apartment is a good investment and its value develops positively | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/unimportant | |

| A good construction quality (e.g., of windows, walls, cooling system, insolation) | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/unimportant | |

| A good noise protection by sound insolation | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/unimportant | |

| Apartment suits to feng shui | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/unimportant | |

| Technical features of the apartment and building support energy-saving | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/unimportant | |

| A great view | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/unimportant | |

| 6.7 | Please answer the following questions about energy-saving, health, and certifications. |

| I would like to know more about solutions that help me to save energy in my home. | |

| I would like to know more about how the indoor climate of my apartment affects the health of my family | |

| I trust the energy certification of electronic devices, e.g., energy star. | |

| 6.8 | Do you know green building certificates like Lotus, EDGE, LEED? |

| If yes, how much do you agree with the following statements? | |

| I trust Green Building certificates, such as Lotus, EDGE, LEED. | |

| I strongly agree/I somewhat agree/so-so/I somewhat disagree/I strongly disagree | |

| when buying my apartment, a green building certificate was important to my decision. | |

| I strongly agree/I somewhat agree/so-so/I somewhat disagree/I strongly disagree | |

| 6.9 | What are the main concerns for your household? Please rate from very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/not important at all for each item. |

| education and career | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/not important at all | |

| leisure and vacation | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/not important at all | |

| spending time with my family | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/not important at all | |

| the energy prices | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/not important at all | |

| family health | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/not important at all | |

| saving for high-value products and services (a car, a travel abroad etc.) | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/not important at all | |

| to live environmental-friendly (e.g., save water and energy, eat less meat, etc.) | |

| very important/somewhat important/so-so/somewhat unimportant/not important at all | |

| END OF QUESTIONNAIRE—THANK YOU FOR YOUR TIME | |

Appendix C

| NỘI DUNG BẢNG HỎI | |

| 1 | THỜI GIAN VÀ NGƯỜI PHỎNG VẨN |

| 1.1 | Phần này giúp (1) xác định người phỏng vấn để kiểm tra lại sau cùng và (2) liên kết bảng câu hỏi với tờ thông tin về tòa nhà. Ngày phỏng vấn (ngày/tháng/năm) |

| 1.2 | Tên người được phỏng vấn |

| Nếu người phỏng vấn dưới 18 tuổi, phải hỏi người khác trên 18 Nếu không có ai trên 18 tuổi, kết thúc cuộc phỏng vấn. | |

| 1.3 | Số điện thoại liên hệ của người được phỏng vấn |

| 2 | THÔNG TIN VỀ TOÀ NHÀ |

| 2.1 | Tên và địa chỉ toà nhà |

| 2.2 | Tên chủ đầu tư/đơn vị phát triển nhà |

| 2.3 | Ngày khởi công/hoàn thành dự án nhà chung cư |

| 2.4 | Loại dự án chung cư (Toà nhà phức hợp nhiều mục đích/Tổ hợp khu đô thị mới) |

| 2.5 | Vị trí địa lý (Trung tâm lõi thành phố/Khu vực kề trung tâm thành phố/Khu ngoại vi mới đô thị hoá |

| 2.6 | Khung giá trung bình/m2. |

| 2.7 | Số tầng (không tính tầng hầm), số căn hộ, mật độ xây dựng |

| 2.8 | Loại chứng chỉ công trình xanh của dự án (nếu có) |

| 2.9 | Toà chung cư có áp dụng giải pháp nào để tăng cường tiết kiệm năng lượng/giảm sử dụng điện (e.g., vật liệu cửa sổ/tỉ lệ giữa tường và cửa sổ/giải pháp tạo bóng râm/năng lượng tái tạo) |

| Dự án chung cư có dịch vụ/cơ sở vật chất nào khác biệt so với các chung cư thông thường khác | |

| 3 | THÔNG TIN VỀ CĂN HỘ |

| 3.1 | Số phòng |

| 3.2 | Tầng |

| 3.3 | Diện tích |

| 3.4 | Hướng |

| 3.5 | Giải pháp tiết kiệm năng lượng (vật liệu cửa sổ, tỉ suất giữa tường và cửa sổ, vv) |

| 4 | THÔNG TIN VỀ NGƯỜI ĐƯỢC PHỎNG VẤN |

| 4.1 | Giới tính |

| Nam/Nữ/Khác | |

| 4.2 | Tuỏi |

| 4.3 | Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị có phải là chủ hộ gia đình không? Ví dụ, Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị có biết mức độ chi tiêu trong gia đình và việc bảo trì căn hộ không? |

| Nếu người phỏng vấn cần phải là chủ hộ. Nếu không cần dừng cuộc phỏng vấn. | |

| 5 | THÔNG TIN VỀ HỘ GIA ĐÌNH |

| 5.1 | Có bao nhiêu người sống trong hộ gia đình Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị |

| Người lớn | |

| 1/2/3/4/5 | |

| Người dưới 18 tuổi | |

| 0/1/2/3/4/5 | |

| 5.2 | Tổng thu nhập của hộ gia đình là bao nhiêu (bằng VNĐ). Người được phỏng vấn có thể không cần chia sẻ thông tin này |

| Dưới 5,500,000/5,500,000–6,499,999/6,500,000–7,499,999/7,500,000–8,499,999/ 8,500,000–9,499,999/9,500,000–10,499,999/10,500,000–11,499,999/11,500,000–12,499,999/12,500,000–13,499,999/13,500,000–14,999,999/15,000,000–29,999,999/30,000,000–44,999,999/45,000,000–74,999,999/75,000,000–149,999,999/150,000,000 và cao hơn | |

| Tích vào ô nếu người được phỏng vấn từ chối | |

| 5.3 | Trình độ học vấn cao nhất trong hộ gia đình |

| Dưới mức trung học phổ thông/Trung học phổ thông/Cao đẳng/Đại học/Thạc sỹ & Tiến sỹ | |

| 5.4 | Trong gia đình có ai được đào tạo ở nước ngoài không? |

| Thạc sỹ | |

| Tiến sỹ | |

| 5.5. | Hộ gia đình Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị có bao nhiêu xe ô tô và xe máy? |

| Ô tô | |

| Xe máy | |

| 5.6 | Gia đình Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị có bất động sản cho thuê không? |

| 5.7 | Hộ gia đình Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị phải trả bao nhiêu phí quản lý dịch vụ căn hộ một tháng? |

| 5.8 | Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị có thể chia sẻ thông tin về chỉ số điện sử dụng của hộ gia đình trong năm 2019 và 2020 không? Thông tin cần được truy cập qua tài khoản với mã số khách hàng trên website của Điện lực Việt Nam (evnhanoi.vn) |

| Tích vào ô nếu người được phỏng vấn từ chối | |

| Sau khi chia sẻ thông tin về chỉ số điện, Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị có thể cho biết thiết bị điện nào sử dụng nhiều điện nhất trong gia đình | |

| 5.9 | Gia đình Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị có bao nhiêu phương tiện/thiết bị nào sau đây? |

| Ô tô điện | |

| Xe đạp điện | |

| Lò vi sóng | |

| TV | |

| Tủ lạnh | |

| Lò nướng | |

| Máy giặt (có hoặc không có máy sấy) | |

| Bình nước nóng (riêng trong căn hộ) | |

| Điều hoà | |

| Quạt điện | |

| Máy rửa bát | |

| Khác | |

| 6 | THÔNG TIN VỀ THÓI QUEN/THÁI ĐỘ CỦA HỘ GIA ĐÌNH |

| 6.1 | Gia đình Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị làm mát căn hộ bằng cách nào? |

| hoàn toàn bằng máy điều hoà/kết hợp giữa máy điều hoà, thông gió tự nhiên và quạt/chỉ bằng quạt (quạt cây, quạt tràn)/hoàn toàn thông gió tự nhiên ở tất cả các phòng/không chắc chắn. | |

| 6.2 | Khi Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị mua thiết bị điện, các yếu tố sau đây có tầm quan trọng như thế nào? Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị hãy chọn một trong các phương án. |

| Giá thiết bị điện có tầm quan trọng như thế nào (như điều hoà, tủ lạnh, bình nước nóng, vv) ? | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Thương hiệu thiết bị điện có tầm quan trọng như thế nào (như điều hoà, tủ lạnh, bình nước nóng, vv) ? | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Nhãn dán năng lượng có tầm quan trọng như thế nào (như điều hoà, tủ lạnh, bình nước nóng, vv) ? | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| 6.3 | Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị có thể chia sẻ thông tin về điều hoà trong gia đình không? |

| Hộ gia đình có tự lắp điều hoà không? | |

| Nhãn dán năng lượng của máy điều hoà của hộ gia đình có mấy sao? Lấy số sao cao nhất trong hộ gia đình | |

| Không có nhãn dán năng lượng/1 sao/2 sao/3 sao/4 sao/5 sao | |

| Thương hiệu máy điều hoà | |

| 6.4 | Gia đình Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị sử dụng điều hoà như thế nào? (khi nào, chế độ, nhiệt độ, việc thay đổi nhiệt độ) |

| 6.5 | Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị đồng ý như thế nào với các mệnh đề sau? Hãy chọn một trong các phương án: rất đồng ý/cũng đồng ý/bình thường/không đồng ý lắm/phản đối. |

| Khi nào có thể, tôi tắt điều hoà và chuyển sang mở cửa sổ và dùng quạt | |

| rất đồng ý/cũng đồng ý/bình thường/không đồng ý lắm/phản đối. | |

| Vào mùa nóng, tôi bật điều hoà suốt đêm trong phòng ngủ | |

| rất đồng ý/cũng đồng ý/bình thường/không đồng ý lắm/phản đối. | |

| Tôi bật chế độ và nhiệt độ điều hoà theo chế độ tiết kiệm điện | |

| rất đồng ý/cũng đồng ý/bình thường/không đồng ý lắm/phản đối. | |

| Tôi tắt điều hoà sau một thời gian vì nhiệt độ trong phòng trở nên quá lạnh/quá nóng | |

| rất đồng ý/cũng đồng ý/bình thường/không đồng ý lắm/phản đối. | |

| Tôi đóng cửa sổ vì tiếng ồn bên ngoài làm tôi khó chịu | |

| rất đồng ý/cũng đồng ý/bình thường/không đồng ý lắm/phản đối. | |

| Tôi đóng cửa sổ để tránh bụi và ô nhiễm bên ngoài | |

| rất đồng ý/cũng đồng ý/bình thường/không đồng ý lắm/phản đối. | |

| 6.6 | Khi mua căn hộ chung cư, các yếu tố sau đây tác động như thế nào đến quyết định của Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị. Xin chọn một trong các phương án rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng |

| Dịch vụ đi kèm trong toà nhà (Bể bơi, cửa hàng, sân chơi, phòng tập gym, vv) | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Căn hộ ở hướng mát, không bị ảnh hưởng bởi mặt trời, và thời tiết. | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Vị trí chung cư, gần nơi làm việc, gia đình, trường học | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Gíá căn hộ/m2 | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Phòng sáng và cửa sổ to | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Thông gió tự nhiên của các phòng trong căn hộ | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Giá trị căn hộ tăng để làm tài sản đầu tư | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Chất lượng xây dựng và vật liệu trong căn hộ (cửa sổ, tường, vv) | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Căn hộ được chống ồn tốt | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Phong thuỷ của căn hộ | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Đặc tính kỹ thuật của căn hộ và chung cư giúp tiết kiệm năng lượng | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Một cái nhìn tuyệt vời | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| 6.7 | Xin Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị cho ý kiến về các mệnh đề sau |

| Tôi muốn tìm hiểu các giải pháp giúp tôi tiết kiệm năng lượng cho căn hộ của mình | |

| Tôi muốn biết điều kiện vi khí hậu trong căn hộ ảnh hưởng đến sức khoẻ của gia đình tôi như thế nào | |

| Tôi tin tưởng nhãn dán năng lượng phản ánh đúng chất lượng tiết kiệm điện của các thiết bị | |

| 6.8 | Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị có biết các chứng chỉ công trình xanh như Lotus, EDGE, LEED không? |

| Nếu có, Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị đồng ý như thế nào với các mệnh đề sau | |

| Tôi tin các chứng chỉ công trình xanh | |

| rất đồng ý/cũng đồng ý/bình thường/không đồng ý lắm/phản đối. | |

| Khi mua căn hộ chung cư, việc dự án có chứng chỉ công trình xanh ảnh hưởng đến quyết định của tôi | |

| rất đồng ý/cũng đồng ý/bình thường/không đồng ý lắm/phản đối. | |

| 6.9 | Mối quan tâm của gia đình Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị là gì. Xin Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị lựa chọn một trong các phương án sau: rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng |

| Giáo dục và sự nghiệp | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Vui chơi, kỳ nghỉ | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Dành thời gian cho gia đình | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Chi phí sử dụng năng lượng | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Sức khoẻ gia đình | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Tiết kiệm tiền để mua phương tiện đắt tiền (xe ô tô) hoặc đi du lịch | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| Sống thân thiện với môi trường (tiết kiệm nước, điện, giảm ăn thịt, vv) | |

| rất quan trọng/cũng quan trọng/bình thường/không quan trọng lắm/hoàn toàn không quan trọng | |

| KẾT THÚC PHỎNG VẤN—CẢM ƠN SỰ THAM GIA CỦA Bác/Cô/Chú/Anh/Chị | |

References

- United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects 2018, Highlights; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pineo, H.; Glonti, K.; Rutter, H.; Zimmermann, N.; Wilkinson, P.; Davies, M. Urban health indicator tools of the physical environment: A systematic review. J. Urban Health 2018, 95, 613–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatzweiler, F.W.; Boufford, J.I.; Pomykala, A. Harness urban complexity for health and well-being. In Urban Planet Knowledge towards Sustainable Cities; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, M.; Brown, C.; Caiaffa, W.T.; Capon, A.; Corburn, J.; Coutts, C.; Crespo, C.J.; Ellis, G.; Ferguson, G.; Fudge, C.; et al. Cities and health: An evolving global conversation. Cities Health 2017, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, H.; Grant, M. A health map for the local human habitat. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health 2006, 126, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, R.J. Constancy and change: Key issues in housing and health research, 1987–2017. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, D.; Gola, M.; Appolloni, L.; Dettori, M.; Fara, G.M.; Rebecchi, A.; Settimo, G.; Capolongo, S. COVID-19 and living space challenge. Well-being and public health recommendations for a healthy, safe, and sustainable housing. Acta Biomed. Atenei Parm. 2020, 91, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, M.; Dahlgren, G. What can be done about inequalities in health? Lancet 1991, 338, 1059–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, H.; Davis, G.; Guise, R. Sustainable Settlements: A Guide for Planners, Designers and Developers; Local Government Management Board: Bristol, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, H.; Grant, M.; Guise, R. Shaping Neighbourhoods: For Local Health and Global Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, H. A health map for urban planners. Built Environ. 2005, 31, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ige-Elegbede, J.; Pilkington, P.; Orme, J.; Williams, B.; Prestwood, E.; Black, D.; Carmichael, L. Designing healthier neighbourhoods: A systematic review of the impact of the neighbourhood design on health and wellbeing. Cities Health 2022, 6, 1004–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R.J. Collective and creative consortia: Combining knowledge, ways of knowing and praxis. Cities Health 2020, 4, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrick, C. An urban health worthy of the post-2015 era. Environ. Urban. 2016, 28, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Environmental Program (UNEP). Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction: Towards a Zero-Emission, Efficient and Resilient Buildings and Construction Sector; UN Environmental Program (UNEP): Nairobi, Kenya, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- REN21. Renewables 2023 Global Status Report Collection, Renewables in Energy Demand, 2023; REN21 Secretariat: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Retzlaff, R. Developing policies for green buildings: What can the United States learn from the Netherlands? Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2010, 6, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Skitmore, M.; Gray, M.; Zhang, X.; Olanipekun, A.O. Will green building development take off? An exploratory study of barriers to green building in Vietnam. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastenrath, S.; Braun, B. Sustainability transition pathways in the building sector: Energy-efficient building in Freiburg (Germany). Appl. Geogr. 2018, 90, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Horr, Y.; Arif, M.; Kaushik, A.; Mazroei, A.; Elsarrag, E.; Mishra, S. Occupant productivity and indoor environment quality: A case of GSAS. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2017, 6, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Meyfroidt, P. Land use transitions: Socio-ecological feedback versus socio-economic change. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Market Research Vietnam, The Growth of the Construction Industry in Vietnam. Available online: https://www.researchinvietnam.com/insight/growth-of-the-construction-industry-in-vietnam (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Nguyen, T.T.; Trevisan, M. Vietnam a country in transition: Health challenges. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2020, 3, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Continuous Growth of Housing Need in Vietnam. Available online: https://tapchitaichinh.vn/thi-truong-tai-chinh/nhu-cau-nha-o-tiep-tuc-tang-trong-thap-ky-toi-330828.html (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Vietnamese Government, Decision 2127/QĐ-TTg, approving the Vietnamese National Housing Development Strategy. 2011. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/EN/Bat-dong-san/Decision-No-2127-QD-TTg-approve-the-national-strategy-on-housing-development (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Vietnamese Government, Housing Law. 2014. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/EN/Bat-dong-san/Law-No-65-2014-QH13-on-housing (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Nguyen, H.T.; Gray, M. A review on green building in Vietnam. Procedia Eng. 2016, 142, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, H.; Francisco, A.; Khosrowpour, A.; Taylor, J.E.; Mohammadi, N. Method for visualizing energy use in building information models. Energy Procedia 2017, 142, 2541–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotus Projects. Available online: https://vgbc.vn/danh-sach-du-an-lotus/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Pham, D.H.; Lee, J.; Ahn, Y. Implementing LEED v4 BD+ C projects in Vietnam: Contributions and challenges for general contractor. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, T.Q.; Truong, N.H.; Hieu, N.T.; Hung, N.M.; Nazird, S. Vietnam general contractors’ perceptions on challenges to the delivery of green building projects. J. Sci. Technol. Civ. Eng. 2022, 16, 116–128. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, P.T.; Chan, E.H.; Poon, C.S.; Chau, C.K.; Chun, K.P. Factors affecting the implementation of green specifications in construction. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Leeuw, E. Global and local (glocal) health: The WHO healthy cities programme. Glob. Chang. Hum. Health 2001, 2, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potrč Obrecht, T.; Kunič, R.; Jordan, S.; Dovjak, M. Comparison of health and well-being aspects in building certification schemes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, J.J.; Powell, C. Health and wellness in commercial buildings: Systematic review of sustainable building rating systems and alignment with contemporary research. Build. Environ. 2020, 171, 106635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illankoon, I.C.S.; Tam, V.W.; Le, K.N.; Shen, L. Key credit criteria among international green building rating tools. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WELL Certified. Available online: https://www.wellcertified.com (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Fitwel Certification. Available online: https://www.fitwell.org (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Ding, Z.; Fan, Z.; Tam, V.W.; Bian, Y.; Li, S.; Illankoon, I.C.S.; Moon, S. Green building evaluation system implementation. Build. Environ. 2018, 133, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilakaratne, R.; Lew, V. Is LEED leading Asia?: An analysis of global adaptation and trends. Procedia Eng. 2011, 21, 1136–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, R.T.; Pope, C.A., III; Ezzati, M.; Olives, C.; Lim, S.S.; Mehta, S.; Shin, H.H.; Singh, G.; Hubbell, B.; Brauer, M.; et al. An integrated risk function for estimating the global burden of disease attributable to ambient fine particulate matter exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, R.D.; Rajagopalan, S.; Pope, C.A., III; Brook, J.R.; Bhatnagar, A.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Holguin, F.; Hong, Y.; Luepker, R.V.; Mittleman, M.A.; et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010, 121, 2331–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.G.; MacNaughton, P.; Laurent, J.G.C.; Flanigan, S.S.; Eitland, E.S.; Spengler, J.D. Green buildings and health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2015, 2, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, C.L.; Needy, K.L.; Ries, R.; Hupp, D.; Bilec, M.M. Building design and performance: A comparative longitudinal assessment of a Children’s hospital. Build. Environ. 2014, 78, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNaughton, P.; Cao, X.; Buonocore, J.; Cedeno-Laurent, J.; Spengler, J.; Bernstein, A.; Allen, J. Energy savings, emission reductions, and health co-benefits of the green building movement. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2018, 28, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragge, P.; Lauren, N.; Pattuwage, L.; Waddell, A.; Lennox, A. Co-benefits of sustainable building and implications for Southeast Asia. In Review Document. Melbourne, Australia: MSDI Evidence Review Service, Monash University and Global Buildings Performance Network; Monash University: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Elnaklah, R.; Walker, I.; Natarajan, S. Moving to a green building: Indoor environment quality, thermal comfort and health. Build. Environ. 2021, 191, 107592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.H.; Qian, Q.K.; Lam, P.T. The market for green building in developed Asian cities—The perspectives of building designers. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 3061–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah-Attipoe, J.; Reponen, T.; Salmela, A.; Veijalainen, A.M.; Pasanen, P. Susceptibility of green and conventional building materials to microbial growth. Indoor Air 2015, 25, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, K.J.; Gibbs, D.C. Towards a sustainable economy? Socio-technical transitions in the green building sector. Local Environ. 2014, 19, 572–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ametepey, O.; Aigbavboa, C.; Ansah, K. Barriers to successful implementation of sustainable construction in the Ghanaian construction industry. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 3, 1682–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.C.; Darko, A.; Olanipekun, A.O.; Ameyaw, E.E. Critical barriers to green building technologies adoption in developing countries: The case of Ghana. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Olanipekun, A.O.; Bai, L. A successful delivery process of green buildings: The project owners’ view, motivation and commitment. Renew. Energy 2019, 138, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubba, S. Green building materials and products. In Handbook of Green Building Design and Construction; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, S.M. Project Management in Construction; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Portnov, B.A.; Trop, T.; Svechkina, A.; Ofek, S.; Akron, S.; Ghermandi, A. Factors affecting homebuyers’ willingness to pay green building price premium: Evidence from a nationwide survey in Israel. Build. Environ. 2018, 137, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintali; SGS Vietnam; Gobal Climate Partnership Fund. (Eds.) Tổng Kết Hoạt Động Công Trình Xanh Năm 2022—Vietnam Green Building 2022 Market Summary. Report on the Occasion of the New Lunar Year 2023; SGS Vietnam Co., Ltd.: Hanoi, Vietnam, February 2023; 4p. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, H.D.; Do, Q.N.; Macchion, L. Assessing Risk Factors in the Implementation of Green Building Projects: Empirical Research from Vietnam. In Asia Conference on Environment and Sustainable Development; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 261–271. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, Q.; Huang, D. Using PLS-SEM to analyze challenges hindering success of green building projects in Vietnam. J. Econ. Dev. 2022, 24, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.; Kim, S.Y.; Luu, T.V. Managerial perceptions on barriers to sustainable construction in developing countries: Vietnam case. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 2979–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Finance Coorporation (IFC). EDGE Certification, Introduction of HausNeo Project. Available online: https://edgebuildings.com/project-studies/hausneo/ (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Durdyev, S.; Ihtiyar, A. Attitudes of Cambodian Homebuyers towards the Factors Influencing Their Intention to Purchase Green Building; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, N.R.N.A.; Shaharudin, M.R. Customer’s purchase intention for a green home. Int. J. Procure. Manag. 2017, 10, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waibel, M. New Consumers as Key Target Groups for Sustainability before the Background of Climate Change in Emerging Economies: The Case of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. In Proceedings of the 5th Urban Research Symposium of the Cities and Climate Change: Responding to an Urgent Agenda, Marseille, France, 28–30 June 2009; World Bank Group, Ed.; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, L.B.W. Middle class landscapes in a transforming city: Hanoi in the 21st century. In The Reinvention of Distinction: Modernity and the Middle Class in Urban Vietnam; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2011; pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, D.; Kwon, Y. In-migration and housing choice in Ho Chi Minh City: Toward sustainable housing development in Vietnam. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bich, P. The Vietnamese Family in Change: The Case of the Red River Delta; Routledge: Oxfordshire, England, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- De Koning, J.I.J.C.; Crul, M.R.M.; Wever, R.; Brezet, J.C. Sustainable consumption in Vietnam: An explorative study among the urban middle class. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phu, L.V. Electricity price and residential electricity demand in Vietnam. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2020, 22, 509–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuters. Vietnam Raises Retail Electricity Price by 3%. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/vietnam-raises-retail-electricity-price-by-3-2023-05-04/ (accessed on 8 June 2023).

| Number | Building Type | Number of Interviews in Each Building Type | Share |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EZ LAND HausNeo | 169 | 30.2% |

| 2 | Other certified green buildings | 31 | 5.5% |

| 3 | High-range non-certified buildings | 94 | 16.8% |

| 4 | Mid-range non-certified buildings | 92 | 16.4% |

| 5 | Low-range non-certified buildings | 174 | 31.1% |

| Total | 560 | 100.0% |

| Apartment Price Per Sqm | Bright Rooms and Big Windows | Good Natural Ventilation of the Rooms | Apartment Investment Value | Good Construction Quality | Fengshui Alignment | Technical Features for Energy Saving | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HausNeo | 1.4 (N = 169) | 1.4 (N = 169) | 1.2 (N = 168) | 1.7 (N = 116) | 1.2 (N = 169) | 2.1 (N = 169) | 1.6 (N = 169) |

| Conventional buildings | 1.7 (N = 363) | 1.6 (N = 345) | 1.5 (N = 363) | 1.7 (N = 358) | 1.4 (N = 363) | 1.7 (N = 345) | 1.6 (N = 362) |

| Total | 1.6 (N = 532) | 1.5 (N = 514) | 1.4 (N = 531) | 1.7 (N = 474) | 1.3 (N = 532) | 1.9 (N = 514) | 1.6 (N = 531) |

| Family Education | Time with Family | Energy Price | Family Health | Saving for High Value Products and Services | Environmentally Friendly Lifestyle | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HausNeo (N = 169) | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1.6 |

| Conventional buildings (N = 345) | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.6 |

| Total (N = 415) | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 1.7 |

| Age Group 18–25 (%) | Age Group 26–40 (%) | Age Group 41–55 (%) | Age Group above 56 (%) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very important | 60 (N = 3) | 87 (N = 86) | 88 (N = 7) | 100 (N = 4) | 86 (N = 100) |

| Somewhat important | 40 (N = 2) | 13 (N = 13) | 13 (N = 1) | 0 (N = 0) | 14 (N = 16) |

| HausNeo | High-Range Market Buildings | Mid-Range Market Buildings | Low-Range Market Buildings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very important | 88% (N = 165) | 87% (N = 64) | 79% (N = 73) | 68% (N = 119) |

| Somewhat important | 12% (N = 23) | 12% (N = 9) | 21% (N = 19) | 26% (N = 46) |

| So so | 0% (N = 0) | 1% (N = 1) | 0% (N = 0) | 5% (N = 9) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, T.T.T.; Waibel, M. Promoting Urban Health through the Green Building Movement in Vietnam: An Intersectoral Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10296. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310296

Nguyen TTT, Waibel M. Promoting Urban Health through the Green Building Movement in Vietnam: An Intersectoral Perspective. Sustainability. 2023; 15(13):10296. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310296

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Thuy Thi Thu, and Michael Waibel. 2023. "Promoting Urban Health through the Green Building Movement in Vietnam: An Intersectoral Perspective" Sustainability 15, no. 13: 10296. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310296

APA StyleNguyen, T. T. T., & Waibel, M. (2023). Promoting Urban Health through the Green Building Movement in Vietnam: An Intersectoral Perspective. Sustainability, 15(13), 10296. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310296