1. Introduction

In recent years, the concept of well-being has gained considerable attention globally [

1], with an emphasis on satisfying human requirements such as enhanced health, work–life balance, commitment, and gender equality in the workplace [

2,

3]. The palm oil industry is pivotal to several nations’ economic growth and development, notably in Southeast Asia [

4]. The expansion of the palm oil industry in Malaysia and Indonesia, particularly on a large scale, has been viewed as diversifying away from rubber production, promoting rural development, and alleviating poverty [

5,

6]. For the industry to maintain its sustainability and success, employee well-being is essential, as satisfied employees in a healthy work environment tend to be more engaged, productive, and committed to their work [

7]. Focusing on employee well-being benefits individual employees and positively impacts the organization’s performance and bottom line. The labor-intensive nature of the palm oil industry has led to contentious issues such as labor shortages, forced labor, and inadequate working conditions [

8,

9]. To prepare for its future, Malaysia requires a sustainable approach to well-being. Unfortunately, over 60% of the forest in the Malay Peninsula and 80% of the rainforest in Sarawak have already been cleared due to various agricultural practices, mining, logging, and urbanization.

These activities have resulted in significant environmental degradation, including tree cover loss, climate change, erosion and sedimentation, floods, water cycle imbalances, and biodiversity loss [

10]. Thus, improving workers’ well-being can enhance the indutry’s reputation, reduce turnover rates and increase productivity [

11,

12].

Given the current challenge faced by the palm oil industry to improve the well-being of its workers, the adoption of sustainable development practices can prove beneficial in fulfilling the needs of stakeholders in both the present and the future [

13]. The stakeholder theory states that organizations ought to prioritize the interests of all stakeholders and establish trust with them [

14]. Regarding this matter, employees and workers are considered critical stakeholder groups and their reactions to an organization’s sustainability efforts are crucial to understanding the social good generated by such initiatives [

15]. Sustainability and employee well-being are interconnected in the palm oil industry. Thus, the industry must prioritize its workers’ physical and mental health and their job satisfaction to achieve long-term sustainability. These sustainable practices can help create a safer, healthier, and happier workplace for laborers, which can improve their well-being. In this vein, during the 39th Palm Oil Familiarization Programme (POFP) in 2019, the Minister of Primary Industries, Teresa Kok, stated that the Malaysian government had implemented policies to promote sustainable oil palm cultivation. One such measure is to set a limit on the total area of land that can be used for oil palm cultivation to 6.5 million hectares. It is aimed at preventing further deforestation and destruction of natural habitats and means that any additional expansion beyond this limit would not be permitted.

While economic sustainability remains essential, the palm oil industry has recognized that neglecting environmental and social factors can have significant long-term economic consequences [

15,

16]. For instance, environmental degradation can harm the productivity and resilience of ecosystems that are essential for the industry’s long-term viability [

17,

18]. Similarly, social conflicts and human rights abuses can undermine the industry’s social license to operate, potentially leading to decreased demand and economic losses [

19]. Thus, stakeholders, including consumers, civil society organizations, and governments, demand a more sustainable approach to the industry, with more significant consideration for environmental and social factors. Although many companies and scholars have been implementing employee well-being and CSR initiatives to address the social and environmental factors of sustainable development in the palm oil industry (e.g., [

20,

21,

22]), the industry has encountered more significant challenges than anticipated in resolving these underlying issues (e.g., [

22,

23]).

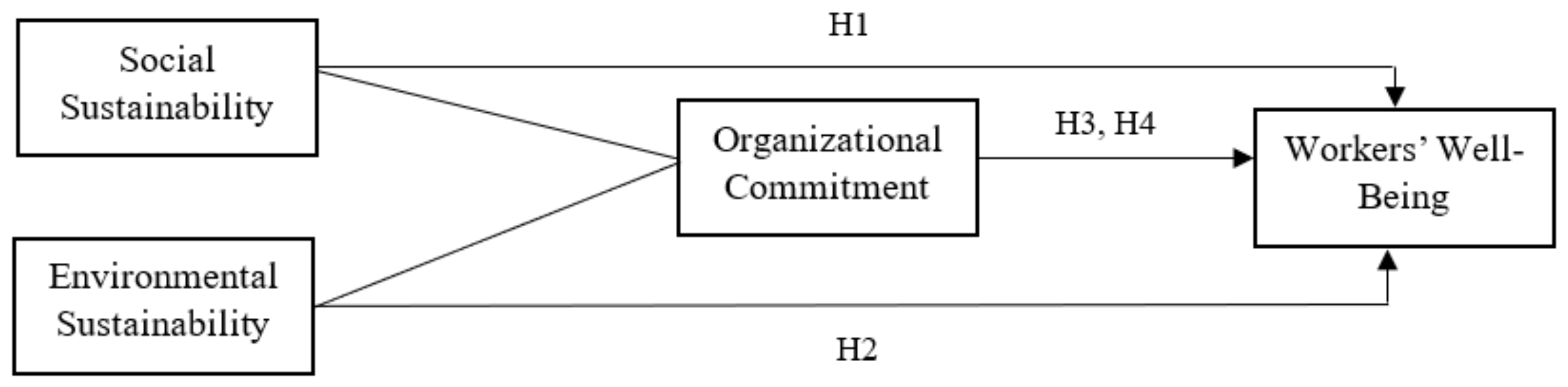

Additionally, limited attention has been devoted to the effects of sustainability in the palm oil industry from workers’ perspectives. Their job satisfaction can play a vital role in boosting corporate identity and reputation [

24,

25]. This study utilizes stakeholder theory to fulfil stakeholders’ requirements [

24]. It expands upon the social exchange theory [

26] for employees’ attitudes and behaviors in an organization by introducing additional variables that contribute to a greater understanding of employee well-being, particularly in the context of social and environmental sustainably factors in the palm oil sector. Therefore, the first objective of this study is to find whether social and environmental factors affect workers’ well-being in the Malaysian palm oil industry.

Moreover, employers face a significant challenge in fostering workers’ organizational commitment [

27]. Based on the social exchange theory (SET), when an organization engages in supportive actions with its employees, it cultivates a sense of organizational commitment [

28]. However, prioritizing sustainability by organizations can create a culture that values social and environmental responsibility, leading to higher levels of employee commitment. Committed workers are more engaged, productive, and satisfied with their work, ultimately promoting their well-being [

29]. Therefore, the second objective of this study is to investigate the potential mediating role of organizational commitment in the association between social and environmental sustainability factors and workers’ well-being in the palm oil industry.

This study makes several contributions to the existing literature. Firstly, it addresses the call made by some previous studies, such as refs. [

30,

31], to expand the empirical evidence on the effects of social and environmental sustainability factors on the well-being of employees, which is crucial for their health, safety, and productivity. This is why organizations must adopt a proactive approach towards environmental issues by utilizing socially acceptable technologies and involving stakeholders in environmental management. Such actions are essential for the industry’s sustainable development and for meeting stakeholders’ expectations. Secondly, it informs the development of sustainable practices and policies that promote workers’ well-being and the industry’s sustainability. Thirdly, this is the first study to examine the mediating effect of organizational commitment on the sustainability factors and workers’ well-being in the palm oil industry. Finally, it helps build a more robust understanding of the linkages between sustainability and employee well-being, which can benefit other industries facing similar challenges. Studying the relationship between sustainable development and workers’ well-being can lead to better outcomes for workers, stakeholders, and the palm oil industry.

The remainder of this study is structured as follows: The subsequent section reviews the relevant literature and outlines the hypotheses. The study’s design is then explained, including details on the sample selection and descriptive statistics, after which the main results are presented. Finally, the discussion and conclusion are provided in the last sections.

3. Research Methodology

This study examines how social and environmental sustainability factors impact workers’ well-being in Malaysia’s palm oil industry. Additionally, the study investigates the mediating role of affective organizational commitment in the relationship between these factors and workers’ well-being.

The research design for this study was quantitative and non-probability sampling, specifically convenience sampling, was used to select the participants. The selection of participants was based on accessibility and approachability. Data were collected through questionnaires distributed during personal visits to four different regions in Peninsular Malaysia, where palm oil plantations were located. A total of 300 questionnaires were distributed; 112 were returned and considered helpful for subsequent analysis, resulting in a response rate of 27 per cent, comprising 66 local employees and 46 foreigner employees. Despite a low response rate, a study conducted by ref. [

65] explains that a survey with a small sample size, such as less than 500, and a response rate of 20–25% and a sample with at least 500 and a response rate of 5–10% is sufficient in providing a fairly confident estimate. The researchers explain that there is no evidence that a high response rate of 80% or higher is an optimum response rate for a survey [

65]. The first possible factor of a low response rate in this study includes employees’ attitudes in answering the questions due to perception-based questions that truly represented their own thinking. The second possible factor might be due to the lack of incentives that were given to the employees; evidently, incentives boost the response rates. The survey was conducted between August 2022 and December 2022 and included palm oil plantation workers aged between 20 to 60 years old.

One set of coded structured questionnaires was created, comprising five (5) sections: profile of the participants, workers’ well-being, social and environmental sustainability, and affective organizational commitment. The questionnaire developed for the present study consisted of a total of 32 items, with 12 items measuring workers’ well-being, that is, job satisfaction adapted from ref. [

64] and workplace health adapted from ref. [

65]; 6 items to measure environmental sustainability adapted from ref. [

64]; 6 items to measure social sustainability adapted from ref. [

64]. It also enclosed six items that measured affective organizational commitment adapted from ref. [

60]. The sample of items used to measure all the constructs, as mentioned above, is provided in

Appendix A.

A five-point Likert-type scale ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree” was employed to measure workers’ well-being, affective organizational commitment, and social and environmental sustainability. The survey questionnaire was designed in both English and the national language of Malaysia (Malay). Research assistants aided in surveying the close supervision of the researchers.

Bu et al. from refs. [

64,

65] stated that a measure is considered reliable when it produces consistent outcomes. Therefore, reliability is widely accepted as a confirmation of the stability and consistency of the instrument [

66,

67]. In this study, the reliability of each instrument examined was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha value, the most commonly used method to test instrument reliability. Prior to distributing the questionnaire, a pilot test was conducted with thirty (30) local plantation workers in a small palm oil plantation in Changloon, Kedah in the northern region of Malaysia to examine the internal consistencies of the instruments using Cronbach’s alpha. Ref. [

66] suggested that a reliability value between 0.70 and 0.90 is generally considered reliable. Typically, a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is regarded as excellent if the value is more significant than 0.90, good if it is around 0.8, acceptable if the value is approximately 0.7, questionable if the value is about 0.6, and weak and intolerable if it is below 0.60 [

66,

67].

Referring to

Table 1 below, the value of Cronbach’s alpha for organizational commitment is 0.917, demonstrating good consistency. For social and environmental sustainability, the values of Cronbach’s alpha are 0.919 and 0.912, respectively, indicating good consistency. Meanwhile, the reliability for job satisfaction and workplace health is 0.861 and 0.843, respectively. All four instruments used were regarded as reliable. In order to examine the content validity of the instruments, two experts from a public university and a manager of a palm oil plantation were involved in reviewing the questionnaire to confirm that all the items used in the instruments evaluate all aspects of the constructs that they are designed to measure. This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

To test the hypotheses, this study follows the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS–SEM) approach appropriate for exploratory study on total variance. The objective is to explain the relationships between exogenous and endogenous constructs. First and foremost, PLS has been confirmed effective by many researchers in exploring relationships between one or more dependent variables from a set of one or more independents [

66,

68]. Furthermore, PLS-SEM is a multivariate technique that permits the simultaneous evaluation of several equations. Finally, refs. [

66,

69] stated that PLS-SEM is able to run factor analysis and regression analysis in a single step [

69,

70].

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper aims to investigate the potential impact of environmental and social sustainability factors on the well-being of workers in the palm oil industry in Malaysia. Further, we examine how mediating roles of affective organizational commitment explain the positive relationship of environmental and social sustainability with workers’ well-being in the palm oil industry of Malaysia.

Previous research has examined the effects of CSR and sustainability on organizational outcomes and employee well-being. This study contributes to the literature by focusing specifically on the well-being of workers in the palm oil industry, which faces challenges in addressing social and environmental sustainability issues [

23,

75]. Given the demanding and labor-intensive nature of the industry, workers’ well-being is of great importance, as they are more likely to experience stressful situations [

62].

Our findings demonstrate that social sustainability is positively associated with workers’ well-being. It encompasses the social aspects of the workplace, including fair treatment, respect, and inclusion, which can lead to higher levels of job satisfaction, stronger relationships with colleagues and supervisors, and a sense of belonging [

41]. These social factors can contribute to workers’ well-being by reducing stress levels, improving mental health outcomes, and increasing motivation and engagement at work [

45,

50]. When workers feel that they are valued and supported by their organization, they are more likely to have positive attitudes towards their work, which can translate into better physical and mental health outcomes. This correlation can be clarified by the social exchange theory, which proposes that workers are incentivized to excel in their work when they believe their organization respects and appreciates them [

28]. Our findings are consistent with previous research showing that investing in social sustainability practices and prioritizing employee well-being can create a supportive and fulfilling work environment (e.g., [

43,

44,

45]).

In addition, our study reveals that the palm oil industry has been scrutinized for its impact on the environment and its contribution to climate change. We find that the environmental sustainability factor positively impacts workers’ well-being. When organizations focus on environmental sustainability, it can create a healthier and safer work environment for workers [

53]. Additionally, an environmentally sustainable workplace can promote a sense of pride and purpose among workers, who may feel more connected to the organization’s values and mission. This positive impact on workers’ well-being is supported by previous research findings [

50,

52,

56].

Our study also finds that affective organizational commitment mediates the relationships between social and environmental sustainability and workers’ well-being. These findings suggest that an organization’s involvement in social and environmental initiatives, such as sustainability practices, can improve workers’ well-being by strengthening their emotional connection to the organization. It helps to explain how the positive effects of sustainability practices can be translated into improved well-being for workers. By understanding the mediating role of affective organizational commitment, organizations can design interventions that not only promote sustainability but also enhance the well-being of their employees. This finding aligns with earlier research that has demonstrated a positive association between having a meaningful work purpose and employees’ commitment to the organization [

76]. Specifically, employees who derive a sense of pride from working for a socially responsible organization are more likely to form a strong emotional bond with their employer, resulting in higher levels of well-being. This result is consistent with the previous literature that has identified affective commitment as a vital contributor to employee well-being [

76,

77]. By adopting sustainable practices, employees can feel they are contributing to a greater good and are part of a larger mission, resulting in greater job satisfaction and motivation to work hard. Affective commitment to an organization has been shown to increase the likelihood of workers continuing to work towards the organization’s goals [

21], which can ultimately enhance well-being.

Previous studies have mainly focused on CSR reports and activities in the palm oil industry (e.g., [

24,

25]). This study breaks new ground by examining social and environmental sustainability approaches, workers’ well-being (including workplace health and job satisfaction), and organizational commitment variables within the social exchange theory in the Malaysian palm oil industry context. The findings of this study will significantly benefit academics by expanding our understanding of Malaysian palm oil plantation organizations’ perceptions of the role of sustainability (particularly in environmental and social dimensions) as a long-term strategy that can help develop intangible assets such as long-term performance and reputations. Moreover, this study sheds light on the indirect role of affective organizational commitment in promoting workers’ well-being by enhancing sustainability practices. As such, this pioneering study offers new perspectives and empirical evidence that can inform policymakers and practitioners about the potential benefits of sustainable practices for promoting workers’ well-being in the palm oil industry.

The findings of our study have significant implications, particularly for stakeholders such as consumer goods manufacturers and retailers interested in making investment decisions in the palm oil sector. Our research provides valuable information regarding the effects of sustainability practices on employee/worker well-being, which can inform these stakeholders’ decision-making processes. By considering the impact of sustainability practices on workers’ well-being, investors and analysts can make more informed and responsible investment decisions that align with their values and social responsibility objectives. Moreover, the finding can reduce shareholders’ uncertainty regarding the palm oil sector’s future sustainability practices. Due to their significance in the agricultural industry, palm oil plantation companies face labor shortage issues, while contributing significantly to Malaysia’s GDP [

40,

78,

79]. Therefore, our research findings can provide valuable information to policymakers and the government, such as the ministry of primary industries, in both developed and developing countries to predict the future of employees’ well-being in Malaysia. This includes an explicit policy on employees’ workplace health, such as training in relation to organizational health, safety (i.e., necessary precautions while working in the plantation, working conditions, no discrimination policy, pay-related matters), and knowledge about their workplace. However, the palm oil industry encounters complex challenges such as deforestation, loss of biodiversity, human rights violations, and climate change, which require the transformation of the entire industry. This transformation necessitates the collaboration of all plantation companies and stakeholders committed to addressing these sustainability issues. By collaborating in this manner, employees’ commitment to their work in the plantation will be strengthened and their overall well-being will be improved. Thus, when employees take pride in their work at the plantation site, they experience a sense of comfort and willingness to contribute, leading to increased loyalty and a stronger desire to remain at the plantation site.

This study has some limitations that highlight areas for future research. Specifically, the study focuses solely on the sustainability of environmental and social dimensions, which are critical in the palm oil industry. However, future studies could benefit from a more comprehensive three-dimensional approach that covers all aspects of corporate operation sustainability. This would provide a more precise evaluation of progress towards sustainability and enable companies to develop more effective strategies for achieving sustainable outcomes. Extending the empirical models to other palm oil-producing countries, such as Indonesia, Thailand, Colombia, and Nigeria, would be valuable for future research. The study’s findings suggest that investors and regulators in Malaysia should consider the distinct impacts of social and environmental sustainability factors on the well-being of employees and workers when making investment decisions.