Abstract

The present umbrella review aimed to: (i) analyze review manuscripts on sport management knowledge/competencies/skills; (ii) propose a harmonized, evidence-based, competency framework for a comprehensive understanding of the intertwined relationships between knowledge, competencies, and skills in determining sport managers’ expected working performance and need for training; and (iii) provide insights for a sound implementation of educational curricula. Based on the PRIO guidelines, inclusion criteria encompassed systematic and narrative literature peer-reviewed review manuscripts relevant to sport management knowledge/competencies/skills, published between 2012 and 2022 in English. The search was performed on three databases, resulting in twenty-two retained review manuscripts representing different research topics. From 277 recorded elements, 72 knowledge/competencies/skills items were extracted. Leadership skills, Finance and administration, Marketing, and Effective communication accounted for the highest representation. Based on the identified evidence, a sport management comprehensive framework was developed including: (1) Life-long learning; (2) Necessary knowledge; (3) What is needed to be done; (4) How things get done; (5) Modulating factors; (6) Transversality within the industry; and (7) Dynamic interaction and intertwined relations. In considering the research propositions and relative recommendations for curricula implementation and future research, the present findings could foster the debate for the sustainable growth of this research area.

1. Introduction

Sport is a large, fast-growing, and employment-intensive economic activity, fully settled into mainstream business and with well-established relationships with political, educational, and economic sectors [1,2]. Since its early stages as an academic discipline [2,3,4], sports management (SM) has needed to clearly define its foundational knowledge and to update programs for providing adequate business/administration-related knowledge, competencies, and skills (K/C/S) to sport managers and administrators [3,4,5]. Furthermore, the establishment of international SM bodies (e.g., NASSM, EASM, WASM, and COSMA), the global implementation of formal (e.g., higher education) and non-formal (e.g., vocational) educational paths, and the growing scholars’ interest in SM-related research progressively legitimized SM as an autonomous academic discipline [2,3,6,7]. In this framework, there is a need to continue stimulating research, academic exchange, and collaborations between SM academic and industry stakeholders on dominant field-related trends to adjust academic and vocational training [8].

Recently, a growing body of research has focused on SM educational curricula, employability, sport managers’ attributes, and organizational dynamics within sport organizations (SOs). This process has contributed to strengthening the characterization of the SM foundational knowledge, relevant K/C/S, roles and responsibilities in managing and leading SOs, and teaching/learning methodologies to enhance the whole sector’s professionalization, SM graduates’ preparedness, and employees’ performance [3,4,6,7,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. However, several factors contribute to reinforcing the complexity of this peculiar labor market sector. First, the policy, non-profit, and other sectors are increasingly interested in the educational, health, recreational, and cultural dimensions of sports in society, which bridge the gaps of inequality by bonding different peoples, social classes, religions, nations, etc. [26,27,28,29]. Therefore, there is a need for a universal language to implement programs and actions meeting the needs of a wider population. Second, in being a powerful driver of irrational passions, emotions, and engagement, sport events attract billions of people worldwide and are unique platforms of convergent interest of several stakeholders (e.g., spectators, athletes, coaches, staff, clubs/associations, fans, managers, leaders, governing bodies, policy institutions, and the actors in the business and media sectors), becoming the perfect avenue for entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship of actors interested in gaining a competitive advantage through the sports environment [30,31,32]. Finally, profound differences between SOs in relation to their nature (e.g., public vs. private; non-profit vs. for-profit), size (e.g., governing bodies vs. local sport clubs), organizational structure (e.g., very structured/professionalized vs. less structured/professionalized), and goals (e.g., commercial and social) determine a huge variety of K/C/S related to a range of different tasks (e.g., very limited and/or specialized vs. diverse and/or less specialized and/or spreading across different organizational departments) within different contextual settings [9,11,33].

Effective SM higher educational programs should bridge the gap between industry demands and graduates’ preparedness to prepare graduates for career development in terms of vertical progression and/or horizontal/transversal job mobility [21,34,35]. Thus, a continuous update of scientific evidence could foster SM sustainable growth and innovation of educational contents, delivery, and skills development strategies [14,25,36,37] in relation to different contexts [38,39] and historical contingency [3,40].

In Europe, the reform of higher education supported the establishment of a European academic framework [41]. Furthermore, an international consensus in relation to the main foundational knowledge included in the SM academic paths exists [3,4]. However, curricula and educational approaches vary considerably within, between, and among national contexts, and no specific competency framework and/or guidelines for competence-driven curricula exist [21]. Furthermore, industry demands that employees excel in a variety of C and S (e.g., soft skills, SS; and hard-technical skills, HS) when planning, implementing, coordinating, and evaluating activities and tasks. Therefore, to drive innovation in societal changing conditions and to align with international policies, there is a call for subsuming a theoretical-based approach in educating SM professionals [21,33,42,43]. Actually, a consistent body of research addressed specific K/C/S in SM education for entry, middle, and senior level managers [6,7,9,24]. Furthermore, the European Skills, Competences, Qualifications and Occupations [44] and the International Standard Classification of Occupations [45] recognize SM occupational profiles, highlighting essential and optional K and S. However, fragmented and multifaceted information on relevant K/C/S emerged. Therefore, it is necessary to continue exploring this research area and to structure a comprehensive, evidence-based, and sustainable competency framework for sport managers.

To promote gender equality in SOs, the European Commission recently co-founded the New Miracle Project, which aims to identify relevant C and S education to empower female SM through a tailored training program [46]. Therefore, the purpose of the present umbrella review (UR) was three-fold: (i) to analyze the evidence on the major K/C/S within the SM-related systematic and narrative literature reviews; (ii) to structure a harmonized, evidence-based, K/C/S framework for a comprehensive understanding of the intertwined relationships between knowledge, competencies, and skills in determining sport managers’ expected working performance and consequent need for training; and (iii) to provide insights for a sound implementation of educational curricula and future research directions to foster the debate in this exciting research area.

2. Materials and Methods

This work was conducted as a part of the Erasmus+ Sport Collaborative Partnership “Women—new leader’s empowerment in sport and physical education industry—New Miracle” project, co-financed by the European Commission (Project number: 622391-EPP-1-2020-1-LT-SPO-SCP).

2.1. Protocol and Eligibility Criteria

The present study was based on a modified version of the Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of systematic reviews (PRIO) guidelines [47]. Inclusion criteria for the studies encompassed: (i) a peer-reviewed systematic literature review (SLR) and narrative review (NR) of manuscripts; (ii) scientific contributions published in English in the last ten years (January 2012–December 2022); (iii) the presence of K/C/S listed within the full text, relevant in relation to the research objectives; and (iv) a moderate to strong methodological quality [48,49]. Exclusion criteria were: (i) primary research articles (identified and retained for other research purposes); (ii) not peer-reviewed publications (e.g., book chapters, book reviews, commentaries); (iii) a weak methodological quality [48,49]; and (iv) the absence of cited K/C/S.

2.2. Literature Search Process

The search string applied on three databases (i.e., Google Scholar, SPORTDiscus (EBSCOhost), and Scopus) included: (sport management) AND (competence OR competencies OR skill*), with the asterisk (*) allowing to retrieve similar root (i.e., skill* = skill and skills). Alert notifications after September 2022 until December 2022 (i.e., end of the data collection) were activated in all the included databases to ensure the inclusion of the most updated articles.

2.3. Selection of Studies and Data Extraction

Based on title, keywords, abstract, and full text screening, two researchers from the New Miracle Project Team independently evaluated the retrieved manuscripts, reporting reasons for exclusion. The opinion of a third researcher was required in case of disagreement on eligibility. Then, data extraction included author(s), year of publication, editorial source, geographical context, research setting, applied search range, total number of studies included in the reviews, and main findings including the listed K/C/S within the full text.

2.4. Assessment of the Methodological Quality

An adapted version of the Quality Assessment Tool for Reviews [48] was used to assess the methodological quality of the included SLRs, which proved a reliable appraisal evaluation in several research contexts [50,51]. Eight quality criteria questions were applied (Supplementary Material S1), with 1 pt. assigned to positive (e.g., “Yes”) answers, and 0 pt. to negative (e.g., “No”) or doubtful (e.g., “Can’t tell”) ones, respectively. Based on the scored quality values (range 0–8 pt.), each manuscript was labeled as weak (range: 0–3 pt), moderate (range: 4–6 pt), or strong (range: 7–8 pt). Only moderate and strong quality studies were retained in the final list to avoid the inclusion of SLRs with a weak methodological quality.

Developed as a brief critical appraisal tool for assessing the construct quality of non-systematic articles, the Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA) [49] was applied to NR. This tool includes six items (Supplementary Material S1), to be rated from 0 pt (low standard) to 2 pt (high standard), with 1 pt as an intermediate score, and a maximal summative score of 12 pt. Papers accounting for 1–4 pt, 5–8 pt, and 9–12 pt were categorized as showing weak, moderate, and strong construct quality, respectively. A SANRA ≥ 5 pt threshold was applied to avoid the inclusion of NR showing a weak construct quality.

2.5. Data Analysis

Each included manuscript was critically analyzed to provide major information regarding research purposes and outcomes, also in relation to the present UR’s specific research target (e.g., SM-relevant K/C/S). Extracted data were recorded in an Excel file for data processing, which included thematic analysis for clustering the collected K/C/S and descriptive statistics in relation to the frequency of occurrence (%) of each item.

3. Results

3.1. General Findings from the Umbrella Review

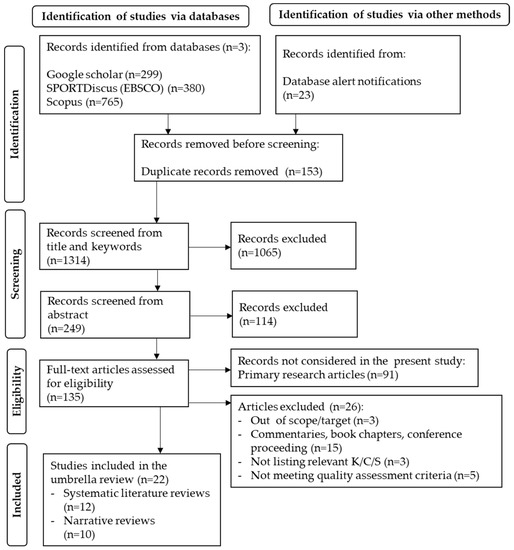

The literature search reported 1467 records. After removal of duplicates, title/keywords screening, and abstract evaluation, 135 papers were retained for further analysis, which excluded 91 primary research articles. From the remaining 48 manuscripts processed for full text evaluation, 26 articles were excluded due to: (i) not meeting the inclusion criteria (n = 15); (ii) out of scope/target (n = 3); (iii) not meeting quality assessment criteria (n = 5); and (iv) lack of relevant K/C/S (n = 3). The final list of included manuscripts (n = 22) included twelve SLRs and ten NRs (Figure 1 and Table 1) published in academic journals ranked from no to first quartile.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the umbrella review process.

Within the considered time frame, eight manuscripts were published after the year 2020, mostly in western countries (Europe: n = 11; North America: n = 8; Oceania: n = 2; Asia: n = 1). For the SLRs, the number of used databases ranged from 1 to 9, including studies ranging from 757 in the bibliometric study of Ciomaga [7] to 19 [52]. Conversely, the manuscripts included in the NRs ranged from 21 [53] to 169 [2].

Independently from the study typology, no contribution reached the highest quality (Table 1 and Supplementary Material S1), with only one SLR [31] showing a strong quality (7 pt), whereas eight NRs [3,25,54,55,56,57,58] presented a strong construct quality (range: 9–11 pt).

Regarding the identified research purposes and outcomes of the included manuscripts, major information is reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Purpose, target, and main outcomes of the included manuscripts.

Table 1.

List of the included manuscripts in the present umbrella review, according to the publication year for SLRs and NRs. The codes refer to the citation order in the text.

Table 1.

List of the included manuscripts in the present umbrella review, according to the publication year for SLRs and NRs. The codes refer to the citation order in the text.

| Code | Authors | Review Type | Country | Journal Abbreviation | Journal Q | Papers Included | Databases (n) | QS | QL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [7] | Ciomaga, 2013 | SLR | Canada | ESMQ | 1 | 757 | 2, and 3 specific journals | 6 | Moderate |

| [28] | Bjärsholm, 2017 | SLR | Sweden | JSM | 1 | 33 | 13 | 6 | Moderate |

| [6] | Miragaia and Soares, 2017 | SLR | Portugal | JoHLSTE | 2 | 98 | 2, and 4 specific journals | 6 | Moderate |

| [30] | Jalonen et al., 2018 | SLR | Finland | OJBM | 0 | 74 | 4 | 4 | Moderate |

| [59] | Megheirkouni, 2018 | SLR | United Kingdom | Choregia | 0 | 44 | 4, and 4 specific journals | 5 | Moderate |

| [60] | Evans and Pfister, 2021 | SLR | Denmark | Int. Rev. Sport Sociol. | 1 | 154 | 1 (main) + 3 (informal search) | 5 | Moderate |

| [9] | Vllasaj, 2021 | SLR | Hungary | OJBM | 1 | 79 | 4 | 6 | Moderate |

| [10] | Yarmohammadi-Monfared et al., 2021 | SLR | Iran | JBSO | 0 | 54 | 9 | 4 | Moderate |

| [52] | Costa and Miragaia, 2022 | SLR | Portugal | Gend. Manag. | 1 | 19 | 2 | 6 | Moderate |

| [29] | Fechner et al., 2022 | SLR | Australia | ESMQ | 1 | 42 | 6 (main) + 1 (forward search) | 4 | Moderate |

| [31] | Lara-Bocanegra et al., 2022 | SLR | Spain | Int. J. Sports Mark. | 2 | 49 | 6 | 7 | Strong |

| [11] | Santos et al., 2022 | SLR | Portugal | SPORT TK | 4 | 65 | 4 | 5 | Moderate |

| [54] | Stylianos, 2013 | NR | Greece | Am. J. Sports Sci | 0 | 137 | 9 | Strong | |

| [3] | Seifried, 2014 | NR | United States | J. Manag. Hist. | 1 | 98 | 10 | Strong | |

| [55] | Demir and Söderman, 2015 | NR | Sweden | ESMQ | 1 | 153 | 11 | Strong | |

| [56] | Peachey et al., 2015 | NR | United States | JSM | 1 | 44 | 11 | Strong | |

| [53] | Pfleegor and Seifried, 2015 | NR | United States | J. Contemp. Athl. | 0 | 21 | 6 | Moderate | |

| [61] | Brandon-Lai et al., 2016 | NR | United States | JASM | 0 | 47 | 7 | Moderate | |

| [57] | Magnusen and Perrewé, 2016 | NR | United States | Sport Manag. Educ. | 3 | 76 | 10 | Strong | |

| [25] | de Schepper and Sotiriadou, 2018 | NR | Australia | Ann. Leis. Res | 1 | 105 | 11 | Strong | |

| [58] | Robinson et al., 2018 | NR | United States | Sport Manag. Educ. | 3 | 97 | 10 | Strong | |

| [2] | Cunningham et al., 2021 | NR | United States | Kinesiol. Rev. | 2 | 169 | 11 | Strong |

Note: Journal Q = journal quartile, assessed using the Scimago journal rank portal. QS = Quality Score; QL = Quality label.

3.2. Critical Synthesis from a SM K/C/S Perspective

The major thematic topics found were as follows: SM as a research area [2,3,7], education [6,25,61], leadership [56,57,58,59], SOs dynamics [9,10,54], business and entrepreneurship in sport [28,30,31], sponsorships [29,55], gender-related issues [52,60], ethical issues in SM [53], and the sport managers’ competency and task profile [11]. Only one study perfectly met the specific purpose of this UR [11]. Because sport managers need to be proficient in a variety of K/C/S, the selected manuscripts addressed different research areas, specific aspects and/or tasks and/or responsibilities in the SM field, and general, specific, and transversal K/C/S. The extracted K/C/S items for each contribution are reported in the Supplementary Material S3.

Regarding the manuscripts focusing on SM as a research topic, the bibliometric study of Ciomaga [7] showed the relevant increase in scholars’ interest in this area, reflecting the progressive search for its legitimacy, and highlighting a growing emphasis on themes that resonate with a commercial logic. In light of the shift towards quantitative research methodologies to enhance the SM scientific rigor and the academic position between other disciplines, the importance of framing the historical development and future growth of SM has been advocated [3]. Furthermore, a comprehensive picture of the SM developmental phases and emerging trends [2] presented a growing focus on the understanding of SOs dynamics and operations through social sciences theories, which produced valuable insights to enhance the management of sport at all levels. As an academic field, SM was found to be fully established and grounded in its foundations, and projected towards further maturation, expansion, and progress, especially given the growing importance of sport as a mechanism to attain various social and humanitarian goals.

For future implementation and research areas on SM education, studies [6,25,61] addressed educational needs, characteristics of academic programs and course design, accreditations, internships/experiential learning, student’s employability, and major C and S. In reconfirming the relevance of SM-related foundational BK, the crucial role of C and S for the implementation of different tasks and activities in SOs emerged. To nurture the student’s skills, pedagogical approaches should consider learning and internship experiences adjusted to the contemporary global dynamics of the industry demands [61]. Specifically, higher educational institutions should combine formal and informal learning methodologies and integrate theoretical learning with activities designed to stimulate the social dimension of students’ critical reflection skills [25].

Leadership and its related skills in sports settings have been investigated in relation to a myriad of styles and behaviors and their related outcomes at individual, dyadic, group, and organizational levels, in both on-the-field (e.g., athletic team) and off-the-field (e.g., management of the SO itself) settings [56]. Four selected studies addressed this topic from an historical/conceptual [56,58], methodological [59], social [57], and educational perspective. In portraying a comprehensive picture of different leadership styles and related research approaches, a lack of mixed methods research designs in this area emerged [59]. To enable a greater understanding of the leadership in the SM field, different leadership styles and modulators have been framed for developing a conceptual model [56]. Furthermore, the crucial role of social effectiveness and skills in sport leaders has been emphasized when considering the social dimension of leadership [57]. Based on the positive outcomes of a centered leading approach motivated by a core altruistic calling and genuine empathy that benefit others, the servant leadership style has been presented as a conceptual model in the field of sport (e.g., the Three-Sphere Model), and teaching activities to educate SM students as future servant leaders have been proposed [58]. In this framework, SM education should consider the implementation of educational curricula with the integration of activities designed to stimulate leadership and political skills to better prepare future leaders.

Leadership research also underpins contextual, cultural, and situational domains, such as ethical issues and gender equality in sport [52,53,60]. Building on the growing ethical misconducts within intercollegiate sports, the need to raise the awareness of sport managers and administrators towards the adoption of ethical decision-making processes has been deemed crucial to sustain their maturity and moral growth, and to guide them towards more effective and efficient decisions concerning ethical dilemmas [53]. Regarding the underrepresentation of women as SOs’ executives due to persistent patriarchal selection practices, gendered language, stereotypes, and organizational cultures reinforcing inequity, the literature on gender-related issues has been critically examined [60]. In this framework, women should be supported in developing outstanding C and S related to the effective management of SOs and entrepreneurship to meet the (extra) challenges of this male-hegemonic labor market sector, which is resilient to change, despite the increase in gender equality policies and concrete actions over the last decades [52,60].

Three studies specifically addressed SOs, particularly as non-profit bodies [9], in relation to the establishment of a meritocracy system [10], and the systematic adoption of personnel appraisal tools [54]. In exploring the literature on the management of non-profit SOs, the relevance of several subtopics emerged regarding organizational capacity, human resources, board and governance strategies, and inter-organizational partnerships, which urge managers and leaders to develop appropriate attributes for enhancing tasks and responsibility management [9]. To promote excellence in managing in a long-term perspective, to avoid corruption and misconduct, and to motivate employees to engage in life-long learning to ameliorate their professional capacities and prospective position, SOs are recommended to establish a meritocracy system for hiring, train good practices based on managers’ actual competencies [10], and systematically evaluate the employees’ performance through valid and reliable tools [54].

Business and entrepreneurship in sport represents another area of converging interests from different actors involved in the process of creating, delivering, and promoting products, with companies consistently investing in elite athletes, top teams, and sports events [28,30,31]. From a value-creation perspective, different actors participating in sports play a role as both value creators and value beneficiaries in this complex context, with sports managers being essential in nurturing the interaction between sport and business [30]. In considering that both for-profit and non-profit SOs share a common interest in value creation to ensure their financial future, sport managers should show special K/C/S in planning and implementing business plans in and through sport perspectives [30]. Aside its financial dimension, sport also plays a crucial role in the promotion of social values. As an emerging interdisciplinary research field in a time of societal change, social entrepreneurship in sport represents a relatively new concept influencing organizations within all sectors of society, particularly the non-profit ones [28]. To develop and implement innovative social-business plans, especially when reacting to diminished governmental budgets and excessive dependence on public funding, managers need to be proficient in a range of C and S, and have appropriate knowledge and awareness of differences existing between social entrepreneurship and other features, such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) and philanthropy [28]. Although a sharp increase in research in this area has been reported, the role of sport has been found to be limited. Therefore, it is crucial to foster the research regarding the precursors and contextual variables leading innovative behaviors, and to implement specific training programs on entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship for SM professionals [28,31].

Another area of critical attention pertains to sport sponsorships, which registered a progressive growth in expenditure attracting high business investments in major small-scale European events [29,55]. Because sponsoring is a strategic lever in professional sport, managers need competence and professionalization in three main strategies (i.e., sponsorship as investment, relation, and animation) to develop specific sponsoring activities (e.g., philanthropic, brand, alliance, dealmaker, activation, and collective sponsoring), which determine relevant consequences for the acquisition, development, and retention of strategic resources across individual, organizational, network, and event levels [55]. Aside from the role of sponsorship in elite sports, charity sport events (CSEs) have also experienced continuous growth, attracting the interest of scholars from the marketing, sport and event management, and psychology disciplines on the social value of sport and its role in the implementation of companies’ CSR strategies and non-profit areas [29]. To mindfully design CSE sponsorship programs, sport managers should be equipped with adequate K/C/S to establish effective, sustainable, and long-term relationship with sponsors, taking into consideration several crucial aspects such as the effective collaboration between managers and sponsor representatives, the event sponsor fit, the long-term perspective in establishing cooperation and agreements, the development of meaningful leverage initiatives to facilitate the sponsor-attendees engagement, and event participants’ segmentation based on appropriate criteria [29].

Finally, only one study was specifically focused on framing sport managers’ competency and task profile, reporting general demographic (i.e., predominantly men in their thirties and forties, with less than ten years of experience in their actual job) and educational characteristics (i.e., mostly the tertiary education level without specific academic education in SM) of sport managers [11]. In considering the lack of professionalization and proficiency in S and C relevant to organizational performance, to accomplish important and time-consuming tasks the need to better educate sport managers in a wide range of K/C/S emerged (e.g., leadership, integrity, specific knowledge, resource allocation, authorities’ delegation, employees’ motivation, and innovative thinking) [11].

3.3. Analysis of Extracted K/C/S

A total of 277 recorded elements emerged from the full text analysis (Supplementary Material S2), labeled into a final list of 72 individual thematic items representing common themes. Seven main categories have been applied to cluster each item:: (1) Background knowledge (BK), including SM theoretical foundations acquired through formal academic degrees and/or certified SM qualifications (i.e., non-formal education); (2) Competencies (C), which is “the ability to meet complex demands successfully through the mobilization of mental prerequisites. Each competence is structured around a demand and corresponds to a combination of interrelated cognitive and practical skills, knowledge, motivation, values and ethics, attitudes, emotions, and other social and behavioral components that together can be mobilized for effective action in a particular context” [62]; (3) General Experience (GE), acquired through personal and/or work experiences in the sport sector; (4) Hard Skills (HS) relevant to employee productivity and efficiency, encompassing technical skills attained through formal, non-formal, and informal education; (5) Personal traits/attributes (PT/A), relatively stable over time and influencing behavior and action in the workplace; (6) Soft Skills (SS), representing non-technical skills pertain inter- or intra-personal dimensions, requested for an array of tasks and activities [63].

Table 3 reports major findings regarding K/C/S data extraction. A frequency occurrence ≥30% was registered for Leadership skills (64%), Finance and administration (55%), Marketing (55%), and Effective interpersonal communication (internal/external) skills (50%); Human resources, Business and entrepreneurship, and Cross-cultural competence (41%), Strategic management (36%), Planning/organization/coordination skills (36%), and Social skills/People skills (36%), Networking (32%), and CSR (32%) were also strongly represented. Another consistent pool of items represented 27% (e.g., Legal and sport policy, Managerial knowledge/experience, Sport-specific knowledge/experience, Communication skills (written/oral), Technological/digital/social media skills, Political skills, Stakeholders management) and 23% (e.g., Sport management education, qualifications, Analytic/evaluation/control skills, Decision Making skills, Sponsorship management, Tasks and resources management, Motivation/Enthusiasm/Passion, Creativity and innovation skills, Ethical commitment and behavior/integrity, Problem solving skills, Teamwork) of the included studies, respectively. Seventeen items accounted for between 18% and 9% of frequency of occurrence, whereas the remaining twenty-six items presented a lower representation.

Table 3.

Frequency of occurrence of the identified K/C/S within the included manuscripts.

Among the top most cited K/C/S (≥25%, n = 19 items), BK was the most cited cluster (n = 6 items), with Finance and administration, Marketing, Human resources, Strategic management and change management, Corporate social responsibility (CSR), and Legal and sport policy considered a crucial theoretical foundation for SM. SS was the second most relevant cluster (n = 5 items), with Leadership skills, Effective interpersonal communication skills (internal/external), Social skills/People skills, Networking, and Political skills considered extremely relevant features in this labor market sector. A lower impact emerged for the other clusters (C = 3 items: Cross-cultural competence, Planning/organization/coordination skills, Stakeholders management; GE = 3 items: Managerial, Sport-specific, and Business and entrepreneurship experience; HS = 2 items: Communication skills (written/oral), Technological/digital/social media skills). Furthermore, no PT/A was considered a fundamental requisite in SM.

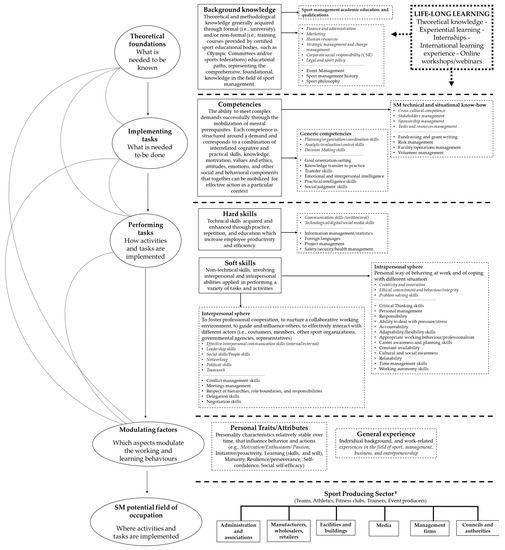

3.4. Harmonized Competency Framework

Based on the main findings presented in the included manuscripts and the K/C/S data extracted in relation to their cluster and relevance (items receiving higher frequency of occurrence are presented first, and in italic font), a K/C/S framework for SM was developed to harmonize results deriving from different research areas (Figure 2). In support of this framework, several research propositions have been formulated with relative recommendations for both SM curricula implementation (SM-CI) and future research (FR).

Figure 2.

The sport management harmonized K/C/S framework.

Proposition 1:

SM education should be a life-long learning process.

Sport managers operating in different contexts and at different levels (e.g., entry, middle, senior) should be encouraged to foster their education in relation to their different training needs, career stage, and situational and/or contextual contingency (e.g., micro level: individual; meso level: organizational; macro level: national context; global level: international context).

SM-CI: integration of different types of learning (e.g., formal, non-formal, and informal); provision of both theoretical and practical learning; adapted pedagogical approaches; internationalization of educational pathways.

FR: harmonization of different learning/teaching approaches within SM curricula; sport managers training needs in relation to their operational context and managerial level.

Proposition 2:

Theoretical foundation—What sport managers need to know.

The present umbrella review confirmed the relevance of several aspects that should be considered to be the core SM knowledge, independently from the potential differences between SM curricula across national and international contexts.

SM-CI: worldwide, SM higher education curricula aligned with international standards in relation to foundational discipline-related knowledge.

FR: cross-national comparisons in relation to curricula content and delivery methodologies; exploitation of best practices.

Proposition 3:

Implementing tasks—What is needed to be done.

The implementation of different activities requires sport managers to be proficient in performing a variety of generic and/or technical/situational C to foster organizational effectiveness.

SM-CI: provision of adequate learning opportunities; development of practical skills and competencies to meet industry demands; fostering of the knowledge transfer to practice to facilitate the transition into the labor market.

FR: further explore managers’ perceived possess, relevance, and performance in relation to their C, also in different organizational and/or national contexts.

Proposition 4:

Performing tasks—How things get done.

Competent sport managers should apply both technical and non-technical skills to increase their efficiency and productivity when performing tasks and activities. In particular, technical skills should be developed to ameliorate working processes from a practical perspective. In both the interpersonal and the intrapersonal spheres, SS help employees to effectively interact with colleagues and/or supervisors and/or other stakeholders, nurturing a collaborative, safe, and respectful working environment.

SM-CI: inclusion of HS and SS training in SM educational programs; implementation of tailored training activities; involvement of industry experts in the development of adequate training activities to better align SM education to labor market demands.

FR: further research on the role of soft skills in managing SOs and their relevance in relation to the different managerial levels.

Proposition 5:

Modulating factors.

Personality traits and previous managerial, sport, and business and entrepreneurship experiences might facilitate sport managers’ career progression and job mobility.

SM-CI: recognition of different types of learning and relevant field experiences; alignment of training programs to actual training needs.

FR: further research on the role of personality traits and previous experiences in modulating career success.

Proposition 6:

Transversality within the industry.

A SM career could occur in different areas of the sport industry. Based on the type of organization, nature, size, structure, and level of professionalization, sport managers could be required to implement different tasks and activities.

SM-CI: a wide variety of K/C/S to ensure adequate opportunities of career development and progression, and potential job mobility; involvement of sport industry experts in SM educational paths (e.g., workshops, seminars, internships); provide students with relevant insights regarding potential occupational opportunities and major expected employability skills in relation to the different labor market areas.

FR: further explore graduates’ preparedness in relation to the different SM-related employment sectors.

Proposition 7:

Dynamic interaction and intertwined relations.

Sport managers’ K/C/S training and performance should be considered a dynamic process rather than a stationary structure. In fact, in executing different tasks, sport managers are required to mobilize their K towards the implementation of adequate solutions through the application of C and S, with previous experiences and personality traits modulating this process. Thus, sport managers are urged to be intellectually dynamic, proficient in variety of aspects, creative, flexible, and smart to implement tailored innovative solutions to actual problems.

SM-CI: develop a comprehensive, holistic educational approach to nurture intellectual dynamicity in sport managers.

FR: investigate the intertwined relations of K, C, S, PT/A, and GE in determining effective SM practices within SOs.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The present UR aimed to provide a comprehensive overview of relevant K/C/S within the SM review literature, taking into consideration different research perspectives represented in the included manuscripts. Major findings substantiate a growing scholars’ interest in deepening the understanding of SM educational and professional contexts, and in providing evidence-based information to align industry demands with educational provision. In particular, the present study confirmed the multifaceted nature of this research area, determining the need to harmonize information from different sectors to effectively adjust SM academic and vocational training. To foster the sustainable growth of the sector and to avoid the disconnect between the labor market and the academic environments in relation to graduates and/or employees’ preparedness, proficiency, and performance, it is crucial to systematically update SM curricula through a multi-stakeholder perspective and a holistic approach. Finally, the present UR represents an original attempt to: (i) provide a comprehensive, evidence-based overview of existing information on SM-relevant K/C/S collected through the analysis of review manuscripts on different research topics; (ii) highlight the relevance of each recorded item through a systematic and reliable approach to data extraction and synthesis; (iii) develop a harmonized and comprehensive framework based on the identification of an appropriate cluster (e.g., BK, C, HS, SS, GE, PT/A) for each recorded item; (iv) remark on the intertwined and dynamic relationship between the proposed clusters, determining appropriate sport managers’ working behaviors and actions in accomplishing activities and tasks and in solving work-related issues (e.g., mobilization of knowledge through tailored competencies and skills); and (v) formulate propositions and guidelines for SM curricula implementation and future research. Therefore, the present findings could be considered a useful tool in fostering the sustainable growth in SM and in providing useful insights to the relevant stakeholders in the sector.

Regarding the major research topics and trends, the retained manuscripts confirmed the complex nature of SM as an academic discipline [2,3,4]. In fact, no prevalence in relation to the identified research topics emerged, with only leadership-related research accounting for four retained studies. This result confirms that SM represents an avenue of convergent interest from a variety of actors, reflecting the need to address this area through a holistic and dynamic perspective in research, educational, and practical domains to nurture multiple K/C/S in sport managers [1,2,3,4,5]. To promote future employability of SM graduates and to enhance sport managers’ effectiveness, the need to integrate the academic and working environments through harmonized educational paths, provision of intertwined theoretical and experiential pedagogical approaches, and learning opportunities emerged [6,25,61,64]. Furthermore, the establishment of inter-institutional cooperation agreements between sport and educational bodies and an international perspective are recommended [4,6,11,40], in line with the European strategies on higher education for universities [65].

The present UM highlighted the need to strengthen the educational focus towards the development of both business and entrepreneurship-related K/C/S, as well as an outstanding cross-cultural competence to meet the challenges related to the social value of sport. In confirming sport as a complex and multifaceted area, sport managers should be able to implement for-profit business plans [30,31,55], efficiently cooperate with sponsors and other stakeholders [29,55], and promote activities addressing the contemporary societal issues [2,28,29,53] through an ethical-based approach [11,53]. Furthermore, the relevance of the non-profit sector [9,28,56] determines the need to continue to professionalize paid staff and leading volunteers within sport organizations to meet the challenges of the working sector and to foster its sustainable growth. Therefore, lifelong learning and periodical vocational training and courses should be encouraged, targeting K/C/S in relation to the different labor market areas, professional profiles, and levels (e.g., entry, middle, senior; leaders in SOs).

The present study substantiates the leading role of Western liberal societies in the SM research area [3,60], with 86% of the included studies performed in European and North American research settings, and the crucial role of international and continental organizations [8] and policy interventions [41,42,43,44] in stimulating the dialogue and exchange between the academic and labor market sectors crucial for nurturing quality education, research, and employability.

Regarding gender, the present UR confirmed the prevalent high imbalance in SOs and the related prejudices/stereotypes regarding the limited women’s management and leadership capability [11,52,54,60]. In fact, a strong male hegemony traditionally characterizes sport governance and management, with the glass ceiling phenomenon influencing women’s career progression towards executive positions. In considering the gender equality quest in society and policy recommendations in this area [66,67,68,69,70,71], the empowerment of all women and girls for having a greater role in sports should be nurtured. Furthermore, to achieve an adequate gender representation in SOs and to increase women’s competitiveness in the labor market, there is a need to implement inclusive and sustainable educational interventions specifically tailored for women managers and new leaders at different career stages, with the ERASMUS+ New Miracle Project representing a best practice.

Regarding the relevant K/C/S, aside from the central role of foundational BK, leadership skills emerge as the most relevant component, being embedded in both SM-specific and not-specific manuscripts. Given its centrality, a better understanding of the different sport leadership styles and contextual modulators, as well as the implementation of tailored activities to educate SM students and leaders, has been recommended [56,57,58]. Moreover, the present study emphasizes the crucial role of C and SS to succeed in this working sector. In fact, SS (e.g., effective communication, networking, social skills, and political skills) and C (e.g., planning/organization, analytic/evaluation, and decision making) accounted for a remarkable frequency of occurrence, suggesting their relevant impact in determining sport managers’ effectiveness. This result confirms that in highly competitive labor market sectors where knowledge and qualifications are not exclusive discriminants of potential candidates, the possession of non-technical skills should not be underestimated [72]. Therefore, SM education should go beyond a theoretical-based approach, incorporating SS and a competency-based approach within traditional curricula [6,25,36]. In fact, in bridging the existing gap between academic and labor market sectors, higher education is urged to overcome its traditional resistance to change and to reflect the changes occurring in business and society, stimulating knowledge transfer to practice, creativity and innovation, and technological and digital skills [2,37,42,73,74]. Coherently, the present UR presents a comprehensive, evidence-based, harmonized, and dynamic framework with relative propositions reflecting the intertwined relations between tasks to be accomplished and solutions to be implemented through the application of a variety of generic and/or specific C and S.

In conclusion, this work not only contributes to enriching the existing knowledge in relation to SM K/C/S, but also fosters the debate in this “exciting” research area. In particular, evidence-based recommendations for curricula adjustments and future research perspectives have been formulated. However, some limitations may have influenced the results. In particular, the restrictive approach used to ensure the quality of the included studies could have influenced the number of identified records and retained manuscripts. Moreover, being specifically focused on review manuscripts, the present study did not consider primary research. Thus, a broader research approach, enlarging the data collection and including different study typologies, might provide additional meaningful insights in this field. Future research should also be envisioned to verify the accuracy of the proposed harmonized framework. Finally, in considering the complex structure of the SM labor market, future studies should investigate relevant K/C/S in relation to the different types of SOs and the different managerial levels.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su15129515/s1, Supplementary Material S1: Quality assessment (QA) of the included manuscripts; Supplementary Material S2: Relevant K/C/S extracted from the selected manuscripts; Supplementary Material S3: PRIO checklist of items to include when reporting an Overview of Systematic Reviews.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.G., S.D., S.C. and L.C.; methodology, F.G., S.D. and L.C.; software, F.G. and S.D.; validation, F.G. and S.C.; formal analysis, F.G., S.D. and S.C.; investigation, F.G. and S.D.; resources, L.C.; data curation, F.G., S.C. and S.D.; writing—original draft preparation, F.G., S.D., S.C. and L.C.; writing—review and editing, F.G., S.D., S.C. and L.C.; visualization, F.G. and L.C.; supervision, L.C.; project administration, F.G.; funding acquisition, L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the ERASMUS+ SPORT PROGRAMME of the EUROPEAN COMMISSION, grant number 622391-EPP-1-2020-1-LT-SPO-SCP.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The present study received external approval by the Erasmus+ Sport Programme of the European Commission financing the “Women—new leader’s empowerment in sport and physical education industry—New Miracle” project (Project number: 622391-EPP-1-2020-1-LT-SPO-SCP9.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

As partners of the Erasmus+ Sport Collaborative Partnership “Women—new leader’s empowerment in sport and physical education industry—New Miracle” project (Project number: 622391-EPP-1-2020-1-LT-SPO-SCP), the authors want to acknowledge the following managers and leaders: Vanagienė A., and Mačianskienė V. (Lithuanian National Olympic Committee); Petronis T. (NGO Inovaciju akademija, Lithuania); Pizzo P. (Italian National Olympic Committee); Gantnerová P. (Slovakian National Olympic Committee); and Taima M. (Latvian National Olympic Committee).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- European Commission. Study on the Economic Impact of Sport through Sport Satellite Accounts. Research Report. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/865ef44c-5ca1-11e8-ab41-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-71256399 (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Cunningham, G.B.; Fink, J.S.; Zhang, J.J. The Distinctiveness of Sport Management Theory and Research. Kinesiol. Rev. 2021, 10, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifried, C. A Review of the North American Society for Sport Management and Its Foundational Core: Mapping the Influence of “History”. J. Manag. Hist. 2014, 20, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifried, C.; Agyemang, K.J.; Walker, N.; Soebbing, B. Sport management and business schools: A growing partnership in a changing higher education environment. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutović, T.; Relja, R.; Popović, T. The constitution of profession in a sociological sense: An example of sports management. Econ. Sociol. 2020, 13, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miragaia, D.A.; Soares, J.A. Higher education in sport management: A systematic review of research topics and trends. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2017, 21, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciomaga, B. Sport management: A bibliometric study on central themes and trends. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2013, 13, 557–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Association for Sport Management. World Association for Sport Management. Available online: https://wasmorg.com/ (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Vllasaj, K. Inspecting the dominant management patterns of nonprofit sport organizations: A systematic review. Cross-Cult. Manag. J. 2021, 23, 90–106. [Google Scholar]

- Yarmohammadi-Monfared, S.; Naghizade-Baghi, A.; Moharamzade, M.; Azizian-Kohan, N. The Importance of Establishing a Meritocracy System in Sports Organizations. Behav. Stud. Organ. 2021, 6, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.M.; Batista, P.; Carvalho, M.J. Framing sport managers’ profile: A systematic review of the literature between 2000 and 2019. Sport TK-Revista Euroam. Cienc. Del Deport. 2022, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eksteen, E.; Malan, D.D.J.; Lotriet, R. Management Competencies of Sport Club Managers in the North West Province, South Africa. Afr. J. Phys. Act. Health Sci. 2013, 19, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Benar, N.; Nejad, R.R.; Surani, M.; Rostami, H.G.; Yeganehfar, N. Designing a Managerial Skills Model for Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) of Professional Sports Clubs in Isfahan Province. Sport Sci. Rev. 2014, 23, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLuca, J.R.; Braunstein-Minkove, J. An Evaluation of Sport Management Student Preparedness: Recommendations for Adapting Curriculum to Meet Industry Needs. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2016, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsitskari, E.; Goudas, M.; Tsalouchou, E.; Michalopoulou, M. Employers’ expectations of the employability skills needed in the sport and recreation environment. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2017, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreffler, M.B.; Schmidt, S.H.; Weiner, J. Sales Training in Career Preparation: An Examination of Sales Curricula in Sport Management Education. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2018, 12, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, D. Analysis of sport sales courses in the sport management curriculum. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2019, 24, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfart, O.; Adam, S.; García-Unanue, J.; Hovemann, G.; Skirstad, B.; Strittmatter, A.-M. Internationalization of the Sport Management Labor Market and Curriculum Perspectives: Insights From Germany, Norway, and Spain. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2020, 14, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ströbel, T.; Ridpath, B.D.; Woratschek, H.; O’reilly, N.; Buser, M.; Pfahl, M. Co-Branding Through an International Double Degree Program: A Single Case Study in Sport Management Education. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2020, 14, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, J.R.; Bosley, A.T. Understanding the Skills and Competencies Athletic Department Social Media Staff Seek in Sport Management Graduates. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2020, 14, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfart, O.; Adam, S.; Hovemann, G. Aligning competence-oriented qualifications in sport management higher education with industry requirements: An importance–performance analysis. Ind. High. Educ. 2022, 36, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duclos-Bastías, D.; Giakoni-Ramírez, F.; Parra-Camacho, D.; Rendic-Vera, W.; Rementería-Vera, N.; Gajardo-Araya, G. Better Managers for More Sustainability Sports Organizations: Validation of Sports Managers Competency Scale (COSM) in Chile. Sustainability 2021, 13, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Carril, S.; Villamón, M.; González-Serrano, M.H. Linked(In)g Sport Management Education with the Sport Industry: A Preliminary Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nová, J. New Directions for Professional Preparation—A Competency-Based Model for Training Sport Management Personnel. In Sport Governance and Operations; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 244–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schepper, J.; Sotiriadou, P. A framework for critical reflection in sport management education and graduate employability. Ann. Leis. Res. 2018, 21, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenger, A.; Schumacher, F. The Social Functions of Sport: A Theoretical Approach to the Interplay of Emerging Powers, National Identity, and Global Sport Events. J. Glob. Stud. 2015, 2, 231–248. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. White Paper on Sport. Available online: https://www.aop.pt/upload/tb_content/320160419151552/35716314642829/whitepaperfullen.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- Bjärsholm, D. Sport and Social Entrepreneurship: A Review of a Concept in Progress. J. Sport Manag. 2017, 31, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fechner, D.; Filo, K.; Reid, S.; Cameron, R. A systematic literature review of charity sport event sponsorship. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalonen, H.; Tuominen, S.; Ryömä, A.; Haltia, J.; Nenonen, J.; Kuikka, A. How Does Value Creation Manifest Itself in the Nexus of Sport and Business? A Systematic Literature Review. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 06, 103–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Bocanegra, A.; Bohórquez, M.R.; García-Fernández, J. Innovation from sport’s entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship: Opportunities from a systematic review. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2021, 23, 863–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woratschek, H.; Horbel, C.; Popp, B. The sport value framework–a new fundamental logic for analyses in sport management. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2014, 14, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrner, M.; Schüttoff, U. Analysing the context-specific relevance of competencies–sport management alumni perspectives. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2020, 20, 344–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, G.; Won, D.; Shonk, D.J. Entry-Level Employment in Intercollegiate Athletic Departments: Non-Readily Observables and Readily Observable Attributes of Job Candidates. J. Sport Adm. Superv. 2012, 4, 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Won, D.; Bravo, G.; Lee, C. Careers in collegiate athletic administration: Hiring criteria and skills needed for success. Manag. Leis. 2013, 18, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schepper, J.; Sotiriadou, P.; Hill, B. The role of critical reflection as an employability skill in sport management. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2021, 21, 280–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Carril, S.; Villamón, M.; McBride, S. Social Media in Sport Management Education: Connecting Universities and Sport Industry. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2020, 20, 3706–3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, E.S.Y.; Kim, C. Construction of Sports Business Professional Competence Cultivation Indicators in Asian Higher Education. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2014, 36, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Eksteen, E.; Willemse, Y.; Malan, D.D.J.; Ellis, S. Competencies and Training Needs for School Sport Managers in the North-West Province of South Africa. J. Physic. Educ. Sport Manag. 2015, 6, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Weese, W.J.; El-Khoury, M.; Brown, G.; Weese, W.Z. The Future Is Now: Preparing Sport Management Graduates in Times of Disruption and Change. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 813504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Higher Education Area and Bologna Process. European Higher Education Area and Bologna Process. Available online: http://www.ehea.info/index.php (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- European Commission. Communication on a European Skills Agenda for Sustainable Competitiveness, Social Fairness and Resilience; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. Skills, Qualifications and Jobs in the EU: The Making of a Perfect match? Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/3072_en.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- European Skills, C.Q. and O. (ESCO). European Skills, Competences, Qualifications and Occupations (ESCO). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/esco/portal/home?resetLanguage=true&newLanguage=en (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO). International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/esco/portal/escopedia/International_Standard_Classification_of_Occupations__40_ISCO_41_?resetLanguage=true&newLanguage=en (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- New Miracle Project. Women’s Empowerment in Sport and Physical Education Industry. Available online: http://www.newmiracle.simplex.lt (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Bougioukas, K.I.; Liakos, A.; Tsapas, A.; Ntzani, E.; Haidich, A.-B. Preferred reporting items for overviews of systematic reviews including harms checklist: A pilot tool to be used for balanced reporting of benefits and harms. J. Clin. Epidemiology 2018, 93, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleddens, E.F.; Kroeze, W.; Kohl, L.F.; Bolten, L.M.; Velema, E.; Kaspers, P.J.; Brug, J.; Kremers, S.P. Determinants of dietary behavior among youth: An umbrella review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA—A scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vet, E.; de Ridder, D.T.D.; de Wit, J.B.F. Environmental correlates of physical activity and dietary behaviours among young people: A systematic review of reviews. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, e130–e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condello, G.; Puggina, A.; Aleksovska, K.; Buck, C.; Burns, C.; Cardon, G.; Carlin, A.; Simon, C.; Ciarapica, D.; Coppinger, T.; et al. Behavioral determinants of physical activity across the life course: A “DEterminants of DIet and Physical ACtivity” (DEDIPAC) umbrella systematic literature review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.; Miragaia, D.A.M. A Systematic Review of Women’s Entrepreneurship in the Sports Industry. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 37, 988–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfleegor, A.G.; Seifried, C.S. Where To Draw the Line? A Review of Ethical Decision-Making Models for Intercollegiate Sport Managers. J. Contemp. Athl. 2015, 9, 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Stylianos, K. Employee Performance Appraisal in Health Clubs and Sport Organizations: A Review. Am. J. Sports Sci. 2013, 1, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, R.; Söderman, S. Strategic sponsoring in professional sport: A review and conceptualization. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2015, 15, 271–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peachey, J.W.; Damon, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Burton, L.J. Forty Years of Leadership Research in Sport Management: A Review, Synthesis, and Conceptual Framework. J. Sport Manag. 2015, 29, 570–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusen, M.; Perrewé, P.L. The Role of Social Effectiveness in Leadership: A Critical Review and Lessons for Sport Management. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2016, 10, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, G.M.; Neubert, M.J.; Miller, G. Servant Leadership in Sport: A Review, Synthesis, and Applications for Sport Management Classrooms. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2018, 12, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megheirkouni, M. Mixed Methods in Sport Leadership Research: A Review of Sport Management Practices. Choregia 2018, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.B.; Pfister, G.U. Women in sports leadership: A systematic narrative review. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2020, 56, 317–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon-Lai, S.A.; Armstrong, C.G.; Bunds, K.S. Sport Management Internship Quality and the Development of Political Skill: A Conceptual Model. J. Appl. Sport Manag. 2016, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychen, D.; Salganik, L. A Holistic Model of Competence. In Key Competencies for a Successful Life and Well-Functioning Society; Rychen, D., Salganik, L., Eds.; Hogrefe and Huber: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Matteson, M.L.; Anderson, L.; Boyden, C. “Soft Skills”: A Phrase in Search of Meaning. Portal Libr. Acad. 2016, 16, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Europass. Validation of Non-Formal and Informal Learning. Available online: https://europa.eu/europass/en/validation-non-formal-and-informal-learning (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- European Commission. European Universities Initiative. Available online: https://education.ec.europa.eu/education-levels/higher-education/european-universities-initiative (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- UN General Assembly. Resolution Adopted on 25 September 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N15/291/89/PDF/N1529189.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- European Parliament. Motion for a European Parliament Resolution on EU Sports Policy: Assessment and Possible Ways Forward. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9-2021-0318_EN.html (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- European Commission. Towards More Gender Equality in Sport—Recommendations and Action Plan from the High Level Group on Gender Equality in Sport. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/684ab3af-9f57-11ec-83e1-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- European Institute for Gender Equality. Gender in Sport. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/publications/gender-sport (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- International Olympic Committee. IOC Gender Equality Review Project. Available online: https://stillmed.olympic.org/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/IOC/What-We-Do/Promote-Olympism/Women-And-Sport/Boxes%20CTA/IOC-Gender-Equality-Report-March-2018.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- International Olympic Committee. IOC Factsheet—Women in the Olympic Movement. Available online: https://stillmed.olympics.com/media/Documents/Olympic-Movement/Factsheets/Women-in-the-Olympic-Movement.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Emery, P.R.; Crabtree, R.M.; Kerr, A.K. The Australian sport management job market: An advertisement audit of employer need. Ann. Leis. Res. 2012, 15, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinkins, L. Innovation Opportunities in Sport Management: Agile Business, Flash Teams, and Human-Centered Design. Sports Innov. J. 2021, 2, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Carril, S.; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Parganas, P. Social media in sport management education: Introducing LinkedIn. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2020, 27, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).