1. Introduction and Background

Overnight, in late winter or early Spring 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted education systems and their activities at all levels worldwide [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Effectively halting centuries of teaching in larger audiences or smaller groups, the pandemic forced education to adapt to online formats since social distancing measures prevented traditional face-to-face teaching in universities [

3,

5,

6].

The teaching innovations in distance or online learning that had already occurred before the pandemic [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], in terms of virtual and visual ways of communicating teaching issues, were heavily depended upon during the pandemic. At that moment, the main goal was to maintain education in any possible way undisrupted at all levels of education [

13,

14,

15]. According to Dagiene et al. (2022), “higher education has transformed and moved online; however, it is not clear whether this transformation produces positive studies outcomes” [

16].

The effects of students shifting from a completely online learning environment during the pandemic to a mix of online and offline teaching modes during [

17] and post-pandemic are unclear. Initial reports suggest that students have changed, but it is uncertain as to why. Is this change a myth? Have students changed? In the post-pandemic period, observably, students’ participatory behavior and engagement have changed. During the pandemic years, students missed interaction with fellow students and friends. What were the repercussions during the post-pandemic period? To understand what happened, we must investigate the students’ perceptions of the different teaching methods implemented due to online conditions.

We need to keep critical conditional factors constant to ensure that we only analyze how students perceived teaching during and post the pandemic. In other words, the research design aims at avoiding (isolating) the effects of other factors of importance on how the teaching is perceived in online versus face-to-face learning situations. First, we will seek out a society with high Information Technology (IT) infrastructure and skills to rule out technical issues. Second, we will identify a seminar that transpires annually with a global theme of similar significance for the students each time. Third, we need to find an established seminar with a similarly high level of teachers. Fourth, we will select a seminar that permits analysis of course-specific likes and dislikes in student feedback. Using these four selection criteria allows us to see the perception change in students without asking directly about the change. In other words, we will explore the possible attitudinal trends of similar students for the same course before, during, and after the pandemic.

One example that fits this criterion is a yearly International Seminar held by a University in Hiroshima, Japan. Since 2006, the seminar has been held in the week marking the tragic destruction of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945. This event collectivizes students from different countries alongside Japanese students. It is a powerful symbol that draws attention to the destructive potential of nationalism, war, and the disastrous effects of nuclear weapons on people and the environment. The seminar uses the history of Hiroshima to engage students in practical discussions about global citizenship and the need for individuals to understand that we are connected as citizens and that our challenges for a sustainable and peaceful future transcend borders. As stated by UNESCO (2015): “Global Citizenship Education (GCED) aims to empower learners of all ages to play an active role, both locally and globally, in building more peaceful, tolerant, inclusive and secure societies.” [

18]. As such, higher education institutions have the task of preparing students as global citizens by facilitating the development of attitudes, values, and skills about their broader responsibility for the interconnectedness of our environment and the well-being of human beings [

19,

20,

21,

22]. In this case, the seminar in Hiroshima aims to provide insight into living as engaged global citizens. It focuses on interdisciplinary topics that cross borders—thinking and solving current human and ecological problems. Professors with extensive experience and backgrounds across various disciplines and topics conduct the workshops in a 10-day program.

In short, the long history of the course qualifies it for this illustrative case. There is a common theme equally important to all students, regardless of their country of origin and professional background. Conjointly, the organizers and teachers collect extensive student feedback as part of the program. This is also the case in the years 2021 and 2022. Furthermore, in 2021 (during COVID-19) and 2022 (post-COVID-19), the organizers and teachers collected extensive student feedback as part of the program.

The seminar in Hiroshima, through its topic and location, invites a high level of shared identification among the participants. The present program satisfies the conditions for a high level of identification around global citizenship-related topics among students, and a high motivation that is already positively biased toward virtual communication. This research focuses on the dynamics within a single setting, studying this social phenomenon in this setting over time using qualitative and quantitative data. Therefore, this is a case study [

23]. Within this setting, the quantitative data from BEVI surveys explore the dynamics of learning effects and pre- and post-COVID test results are compared. Furthermore, the qualitative data from participants’ feedback in the seminar explores the participants’ perceptions regarding online versus face-to-face teaching modes.

As Japan is a highly sophisticated society in terms of advanced IT infrastructure, we rule out the effects of the infrastructure seen in previous research. For example, Chisadza et al. conducted a study investigating the factors that predict students’ performance after transitioning from face-to-face to online learning due to the COVID pandemic at a South African University [

24]. Unlike this case, improving digital infrastructure was not an impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the education system in Japan and the activities are taking place in a context with modern computer facilities with a good internet connection. COVID-19 provides us a valuable opportunity to understand and assess the impact of educational adaptation and its effect based on students’ perceptions during and post-pandemic times.

The aim of this study is to assess the impact of COVID-19 according to students’ perceptions of teaching in an international case seminar during and after the pandemic (2021–2022).

The research questions are stated below:

RQ1: What are perceptions from students’ feedback from going online to face-to-face?

RQ2: How did differences in teaching/learning tools affect the students’ perceptions during the International student seminar?

RQ3: From the students’ perspectives and behavior, what implications does this study suggest for future online global seminars?

According to Selwa Elfirdoussi et al. (2020), online learning refers to education using telecommunications equipment and internet technology [

25]. During the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in the winter of 2020, the equipment and/or support of technologically savvy colleagues became difficult for teachers to access. To achieve greater effectiveness in the shift to online education, the success of these changes relied heavily on developing and accessing information and communication technologies in the country [

13].

Almaiah and Mulhem (2018) point out that design and content are critical drivers for an e-learning system [

26]. In addition, the critical challenges and factors that influenced the e-learning system during the COVID-19 pandemic are related to the following categories: technological factors, e-learning system quality factors, cultural aspects, self-efficacy factors and trust factors [

27]. Fish, Snodgrass and Kim point out in their study in South Korea and the US, based on a comparison of graduate students’ perspectives of online versus face-to-face program characteristics during the pandemic, that the preferences of students with collectivist and individualistic cultures remain to be understood [

17].

According to a survey, students lacked motivation in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic due to stifling social interaction. The study was conducted by the Benesse Education Research and Development Institute and the Institute of Social Science at the University of Tokyo [

28]. The answers were collected from 10,000 students ranging from fourth graders to high schoolers between July and September 2021. The study found a drop in motivation due to reduced interaction among students at schools. COVID-19 has limited students’ interaction and the leisure activities they engage in at school. As a result of this restriction, students expressed a lack of motivation to learn.

The goal of this study is to investigate and analyze the perceptions of student participants who joined the International Student Seminar in 2021 held at a University in Hiroshima, Japan. In order to achieve the goal, in the first part, a quantitative analysis of BEVI data was obtained from the students in the seminar before COVID-19 and after. The result revealed that there are no changes in the way students learn. Secondly, qualitative data was obtained based on students’ perceptions in the survey. The results revealed that based on the perceptions of students of online teaching versus hybrid teaching, there were prominent differences in the students’ perceptions of their learning experience during the pre-pandemic and post-pandemic periods.

This study provided us with an opportunity and insight into our learning about best educational practices for a more inclusive and sustainable future. It is crucial to understand the significance of the international seminar held within this study, as this type of international seminar motivates students from different educational institutions around the world to understand various global issues and consider their actions as global citizens. Analyzing the effectiveness of this type of international student seminar can contribute by providing a pathway to a more inclusive and sustainable world. As the world becomes more interconnected, virtual environments, such as the ones presented within the international student seminar in Hiroshima, Japan is vital to facilitating intercultural teaching environments and the prospective implications of this paper indicate that these virtual mediums can promote inclusion, leading to a more peaceful and sustainable world.

2. Methods and Materials

In this study, we conduct a quantitative and qualitative analysis of students’ feedback collected from the International Student Seminars held at a University in Hiroshima, Japan, in 2021 and 2022. For the quantitative analysis, we use the scale items of BEVI, short for Beliefs and Values Inventory, developed by Shealy [

29,

30,

31]. It is a tool to evaluate training in international courses [

32]. The same questions beliefs and values are answered by the students before the teaching begins and after the teaching ends to see the effects of the teaching. In addition to the four scales previously used to measure the degree of shifts in world view, we added the BEVI scales that were important for the teaching purpose of the course. We report the results following the traditions of how the BEVI results are normally reported.

For the qualitative analysis, we describe the feedback of students that they were asked to provide after the teaching had ended. The feedback was structured around several issues that the teachers wanted to know how the students perceived. Students’ feedback reflects their satisfaction with the seminar content in general. In particular, the students’ feedback also indicates the quality of the various teaching modes and techniques used in the seminar.

The goal of these seminars was to unite students from ten International Seminar member institutions (2021) and nine (2022) internationally to explore how students, as global citizens, can understand the given themes and consider our actions to contribute to the world. In 2021, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the International Seminar was conducted online for the first time (the International Seminar 2020 was canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic), and the year’s theme was “Understanding Global Inequalities: Bridging the Gaps”. The student participants for 2021 consisted of 74 students (40 female, 34 male) from various countries, with predominantly Japanese student participants and numbers from three to 11 regarding participants from other universities. and the 2021 International Seminar student participant demographics are shown in

Table 1 below:

In August 2022, the International Student Seminar was conducted face-to-face after the COVID pandemic settled. This year, the seminar’s theme was “The Age of Artificial Intelligence: Opportunities and Concerns”. The seminar’s goal for 2022 aimed to explore the debate raised by the developments in A.I. The 2022 International Seminar critically considered how A.I. increasingly impacts our day-to-day life, looking at the opportunities and dangers. All the student participants for the 2022 International Seminar attended this International Seminar at a University in Hiroshima from 3 through 12 August 2022. The participants for the International Seminar in 2022 consisted of 48 students in total, with predominantly Japanese participants, and other participant countries ranging from five to two participants. and the 2022 International Seminar student participant demographics are indicated in

Table 2 below:

The 2021 International Seminar was conducted from 5 through 13 August 2021. The student participants were expected to attend all the activities in the seminar online during the program. Contents of the 2021 International Seminar program included a group presentation, four online workshops, two online keynote speeches, online interaction with a Hiroshima A-bomb survivor, an online group introduction story exchange, live streaming of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony, an online Intercultural Learning session, a Japanese language session and presentations on Japanese culture by Japanese students. Students were expected to read materials and on-demand lectures in July in preparation for the August online seminar. In addition, four pre-recorded videos of each workshop and a pre-recorded video by the A-bomb survivor were sent to students. To manage the time difference for the online participants across the globe, the students were allocated into two different groups based on time zones to enable them to work together more efficiently. Two different time slots were allocated for the online group work, depending on where students were in the world. Students from Japan (University in Hiroshima) were especially divided between the two time slots to mix them with students from different cultures to promote intercultural experiences. For example, time slot 1 included students based in the U.S.A., Argentina and Japan and time slot 2 consisted of students based in the U.K., Europe, South Africa, Indonesia and Japan. To promote intercultural experience even in a virtual environment, a group introductions story exchange was implemented. Students from nine universities worldwide joined their peers to get to know each other through story exchange on 9 August 2021. On the same day, all the students attended an online keynote speech together at 22:00–23:00 (Japan Standard Time).

Since COVID-19 restrictions had become more lenient in 2022, The 2022 International Seminar was held face-to-face on-campus in Hiroshima, Japan, from 5 through 13 August 2022. The 2022 International Seminar program included four workshops, two keynote speeches, a meeting with a Hiroshima A-bomb survivor and country group work sessions leading to a U.N. role play. While all activities and programs between 2021 and 2022 were similar, due to the format of the 2022 seminar, the United Nations general assembly role play was re-implemented after being replaced by group presentations in 2021 as conducting a virtual Model U.N. would have been quite challenging for the student participants.

Table 3 below summarizes the differences in program contents between the International Seminars in 2021 and 2022:

The study collected data from an online survey with student participant respondents (both 2021 and 2022) and feedback sessions (online in 2021 and in-person in 2022) with students. One of the authors conducted the feedback sessions as an International Seminar program moderator in both years. Samples of questions from the 2021 and 2022 International Seminars Student Feedback Survey are displayed in

Table 4 below. The full set of questions can further be found in

Appendix A.

3. Results

Within the International Seminar, the primary goal was to collectivize students internationally to interact and communicate over specific global topics. At the end of both seminars, a qualitative feedback analysis survey was conducted to rate students’ satisfaction with portions of the seminar and the experience in its entirety. Researchers chose 2021 and 2022 due to the contrasting formats the seminar was presented—online in 2021 and face-to-face in 2022. Students’ perceptions were analyzed to discern the benefits of an online versus a face-to-face format for international education seminars.

In the sections below, regarding quantitative data, BEVI scores from T1 and T2 are reported, with specific emphasis on changes in the degree of world view. Furthermore, the aggregate profiles for students at the International Seminars (pre- and post-COVID-19 are reported. Regarding qualitative data, the predominant patterns relating to students’ feedback and attitudes regarding 2021 and 2022 were collectivized and detailed below. First, the overall student satisfaction regarding 2021 and 2022 is evaluated. The student satisfaction for specific seminar contents for 2021 and 2022 was then quantified and compared—firstly regarding the aspects that were positively rated and then aspects which students were unsatisfied with. Finally, satisfaction regarding the intercultural activities within each seminar and satisfaction with workshop characteristics was assessed before further commentary, which is presented in the discussion section.

3.1. Possible Trends in Learning Effects Based on Student Participants in the Seminar

BEVI, is a mixed-method measure with scale items (quantitative) and free response items (qualitative).

BEVI is used as an assessment instrument to investigate students’ international, multicultural and transformative learning in teaching situations. BEVI questions are asked before, known as T1 and after the teaching has ended, referred to as T2. The questionnaire contains measures related to the event. It is thus fruitful as we have perceptions of students of the same teaching event from the same kinds of students. We can then explore changes in values and beliefs regarding the questions regarding the experiences of the course.

As this course teaches issues related to the global scene of topics, the measure of BEVI relating to world outlook seemingly is a plausible way to look for teaching effects (

Table 5 and

Table 6).

Seemingly, when observing the different BEVI Scales included in

Table 7, there are observable similar trends between the pre-COVID-19 (2017) and post-COVID-19 groups (2022)—with either an increase in the scales (in the case of Emotional Attunement, Social Openness, Ecological Resonance, and Global Engagement/Resonance) or decreases (Causal Needs Closure). The only scale which differs from this trend is Basic Determinism, where there was a decrease in 2017 and an increase in 2022. As a scale, Basic Determinism refers to the possible preference for simple explanations for observable differences. In the 2017 group, the overall preference for simple explanations went down. In contrast, in the 2022 group, the preference for simple explanations increased. Basically, the trends of learning effects were the same in 2017 and 2022.

3.2. Overall Satisfaction Scores of International Seminar 2021 & 2022 Seminars

The following

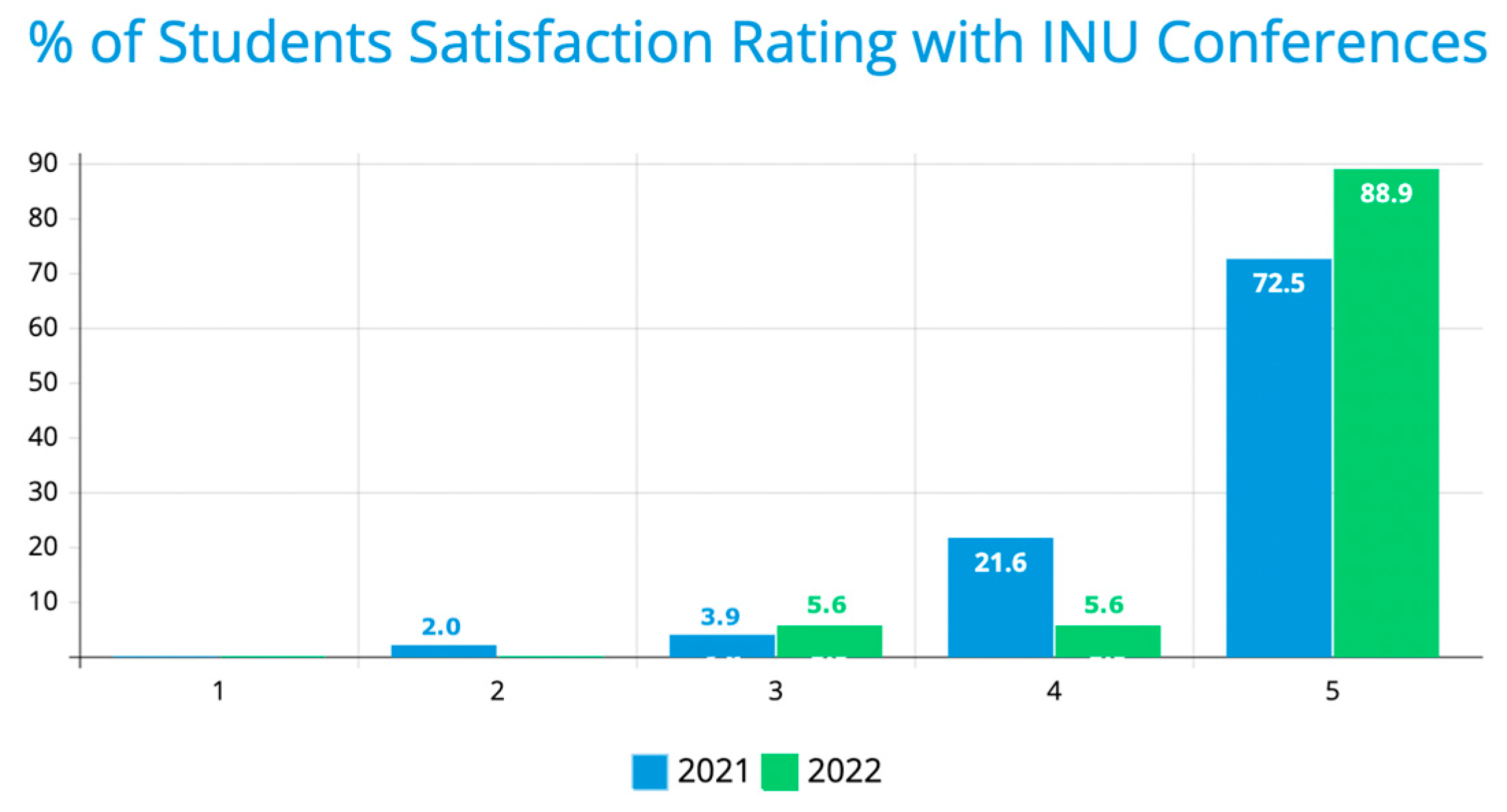

Figure 1 was constructed from analyzing satisfaction scores taken from responding International Seminar participants in post-seminar feedback surveys from International Seminar 2021 (total of 51 feedback responses) and International Seminar 2022 (18 total responses).

The x-axis relates to the overall satisfaction students felt regarding the entire International Seminar each year. A level one rating represents poor satisfaction while a five represents excellent satisfaction. In 2022, the overall level of satisfaction was higher in 2022 than in 2021. There are also fewer lower ratings in 2022 than in 2021, with only 11.6% of scores being lower than a five. In contrast, 27.5% of scores were lower than a level five satisfaction rating in 2021.

3.3. Satisfaction with Specific Seminar Contents

When prompted further about which specific aspects of the seminar they enjoyed most, results were consolidated based on specific aspects within the seminar. The percentages in the table below were taken by calculating the percentage of how many students stated a particular portion of the event over the total amount of feedback responses. It should be noted that the “trips” category is only applicable to 2022, as no trips occurred in the online 2021 seminar. The results of these calculations are as

Figure 2 shows:

For 2021 and 2022, intercultural communication was rated as the most enjoyable portion of the seminar—64.3% in 2021 and 50.0% in 2022. Events within this category permitted participants to communicate interculturally with other participants. Examples include the break-out rooms in 2021 and in-person group study sessions in 2022.

Furthermore, in 2021, keynote presentations/workshops and intercultural learning experiences (such as the Japanese language/culture sessions) are tied for second, with 14.3% stating it was the most enjoyable. The final group presentations in 2021 were also mentioned as the favorite by 7.1% of participants surveyed. In 2022, this changed as the UN Role-Play placed as the second most enjoyable aspect of the International Seminar, with a score of 16.7%. Other aspects, such as intercultural learning experiences, keynotes/workshops, and trips, tied for third with a score of 11.1%.

3.4. Perceived Dissatisfaction with Program Contents 2021

Conversely, when prompted about which aspects they disliked about the seminar, in 2021, students mainly criticized the online format—with 24.5% of respondents mentioning it in their responses, as demonstrated by the student statement, “It was quite tiring sitting in front of a laptop. Hopefully next time it will be in person!” Additionally, complaints regarding the online format prevailed in responses about other disliked issues, such as time zones and timing—with 12.2% of responses about timing stating similar accounts to the student quote, “It may not be about seminar, but the sessions are conducted on later night, so sometimes it was hard for me to keep my concentration”.

The virtual formatting of the International Seminar 2021 also influenced the responses of 12.2% of students in 2021 who stated the intercultural learning experiences were the least enjoyable—as shown by the statement below:

“The shorter workshops on culture and language. I do think it is a great idea to include culture exchange and knowledge in the workshop, but due to the online format and the short amount of time, I felt I couldn’t fully dip into the sessions.”

Moreover, issues with the language barrier comprised 12.24% of surveyors’ responses. Conjointly, issues with keynote/workshops comprised 18.4%, and 22.5% of applicants stated no issues or dislikes.

3.5. Perceived Dissatisfaction with Program Contents 2022

Comparatively, in 2022, 27.8% of survey participants critiqued the keynote speeches and workshops the most. Notably, many students expressed their dislike of the online format of keynote speeches, as portrayed in the quote below:

“Keynote speakers’ lectures were very interesting, but I prefer face-to-face lecture. Online lecture sometimes allow me to left behind because it is more difficult to ask someone else”

The second most mentioned critique in 2022 regarded timing and the in-person format (16.7% of responders for both, respectively). Specifically, students mentioned issues with jetlag or the packed schedule of the International Seminar concerning timing and issues with finding transport and remaining pandemic restrictions for critiques concerning the in-person format. The latter of which is expressed through feedback responses such as the one displayed below:

“The only thing I did not enjoy was something that was out of our control due to covid so I understand, but it would have been nice to have the arrival reception and end of the seminar reception for lack of a better word. There were not many opportunities for everyone to interact together outside of the workshop and country groups and it would have been nice to have that time to bond with one another and get to know each other better as well as end it off together.”

The remaining 11.1% of responders labeled issues with language barriers as the least enjoyable portion of the 2022 International Seminar and 27.8% of answering participants stated no dissatisfaction.

3.6. Students’ Satisfaction with Intercultural Activities 2021 & 2022

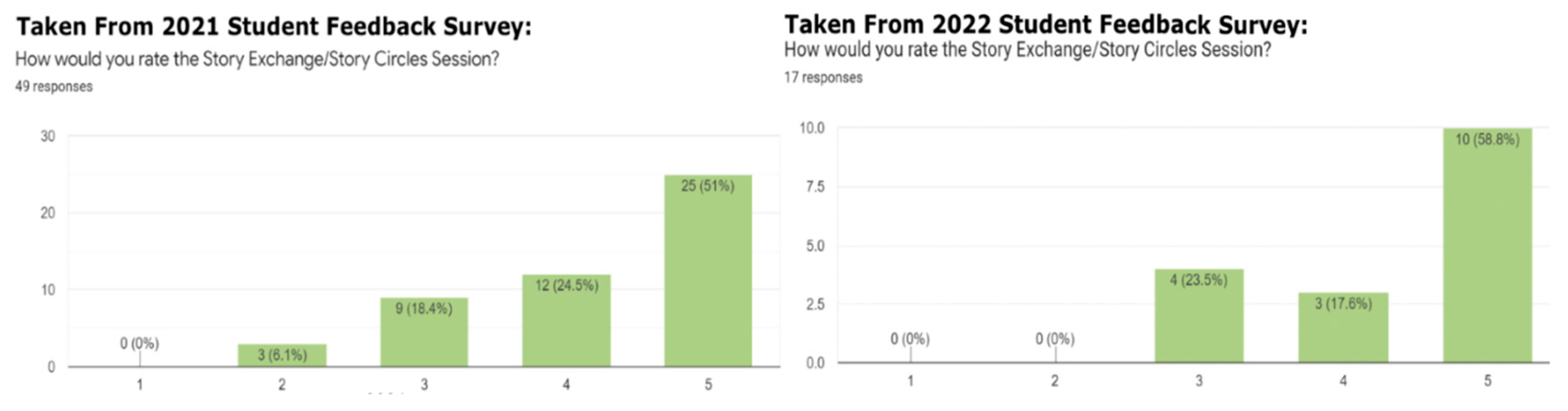

When prompted specifically about the satisfaction students felt regarding intercultural activities—with the most popular being the Japanese cultural exchanges and the story exchange/circles. For the story exchange sessions, there was an increase from 51% to 58.8% in the highest satisfaction (please refer to

Figure 3) from 2021 to 2022. A similar increase is observed regarding the Japanese culture sessions, where the highest level of satisfaction increased from 70% in 2021 to 100% in 2022 (please refer to

Figure 4). This increase was especially evident in the events that switched from online to in-person. The graphs below contrast how students rated specific intercultural activities—story exchange circles (conducted online in both years) and Japanese Culture sessions (conducted online in 2021 and in-person in 2022).

Story Exchange Sessions (2021 & 2022):

Figure 3.

Percent of Student Satisfaction Rate with Story Exchange Sessions.

Figure 3.

Percent of Student Satisfaction Rate with Story Exchange Sessions.

Japanese Culture Session:

Figure 4.

Percent of Student Satisfaction Rate with 2021 and 2022 Japanese Culture Sessions.

Figure 4.

Percent of Student Satisfaction Rate with 2021 and 2022 Japanese Culture Sessions.

The feedback responses regarding the Japanese culture session are evidence of satisfaction increase after a transfer to in-person, as the highest satisfaction ratings increased from 70% of participants in 2021 to 100% in 2022. In events that stayed online both years, such as the story exchange/story circles seminar, there was a general increase in overall satisfaction with lower scores of two, three and four, collectively decreasing from 49.2% in 2021 to 41.1% in 2022.

3.7. Satisfaction with Portions of the Workshops

Pertaining to workshops, students were also prompted about the most enjoyable aspects. Furthermore, in 2022, students were asked about the least enjoyable aspect, too. When prompted in 2021, 51.0% of student feedback discussed specific lecture topics as the most enjoyable, while 34.0% stated that communication portions such as breakout rooms and “discussion groups with students on the topics” were the most enjoyable—which is prevalent within the student quote below:

“I enjoyed that we learned poverty and inequality from intersectional perspective. It has allowed me to gain a bigger picture how the situation arises and impacts. Also, I enjoyed moments when we worked in small group sessions. It helped to engage in an interactive learning process and exchange information.”

The 14.9% of remaining feedback responses provided critiques, expressing students’ dissatisfaction with the need for more interaction and less time for keynote speakers (71.4% of total critiques). The remaining 28.6% of critiques addressed the workshop topic choice and group project. Regarding the most enjoyable portion of the workshops in 2022, 75% of feedback responses expressed that discussions in workshops were the most enjoyable portions of the lecture. The remaining 25% expressed enjoyment in specific portions of lectures. Each of these notions is expressed below:

“I enjoyed Tutik lecture the best. I could get the confidence to express my opinion in English because she made positive atmosphere to hear others’ opinions on the classroom. The warm mood looked like to have been shared among all classmates.”

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study is to investigate and evaluate the perceptions of student participants who joined the International Student Seminar in 2021 and 2022 on global citizenship and peace held at a University in Hiroshima, Japan. In the first part of a quantitative analysis of BEVI data obtained from the students in the seminar before COVID-19 and after, the result revealed that there are no changes in the way students learn. However, in the second part of qualitative data, results showed that based on the perceptions of students of online teaching versus hybrid teaching, there were prominent differences in the students’ perceptions of their learning experience during the pre-pandemic and post-pandemic periods. Overall, according to the tables and data presented above, the overall satisfaction with the International Seminar conferences increased between 2021 and 2022 after transitioning from a virtual conference to a face-to-face. In both instances, communication and interaction with other student participants and the specific International Seminar topics were the most enjoyable aspects of the seminars. In contrast, issues with the virtual setting and time zone characterized many complaints submitted in the 2021 participant feedback survey. Moreover, issues with workshop duration and online format, as well as the issues with the language barrier, were characteristic of the critiques in the 2022 survey.

As

Figure 1 indicates from the 88.9% of feedback respondents in 2022 rating the overall seminar as a “five” in contrast to the 72.5% of respondents in 2021 giving the same rating, students tend to prefer face-to-face formatting instead of online for these types of seminars. Nevertheless, it is vital to consider the discrepancies in satisfaction. While the students were generally more satisfied with 2022 than 2021, there are instances where satisfaction was higher in 2021 than in 2022. This begs the question, if students were generally happier with 2022 than 2021, why were certain parts of the seminar approved more highly in 2022 than in 2021 and vice-versa? Individual portions of the seminar must be evaluated—such as the workshops, keynote speeches, cultural activities and the final presentation/model UN role-play. When doing so, there is an observable pattern that is presented—indicating that student satisfaction is not necessarily consistently higher when presented with a face-to-face format but instead is higher when there is an emphasis on participation communication in these types of seminars—specifically those that stress intercultural awareness, experience and understanding. Therefore, the face-to-face format is generally preferred as there are usually more opportunities for communication and discussion in the traditional learning setting. However, creative online teaching modes that stress the importance of interaction (for example, via breakout rooms) can lead to higher satisfaction overall.

When looking at the results of students’ feedback survey on specific events and programs (i.e., field trips, keynotes, workshops, etcetera) in 2021 and 2022, we can see notable differences in students’ perceptions and responses based on various factors. Their perceptions were analyzed to identify the benefits of virtual versus face-to-face platforms offered in 2021 and 2022. Firstly, regarding the question, “What is your most enjoyable portion of the seminar?” intercultural communication and activities were rated as the most enjoyable, 64.3 percent in 2021 and 50 percent in 2022. In both years, student participants were encouraged to communicate with students from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Despite the virtual platform in 2021, students still rated intercultural activities the most enjoyable among all other online programs offered in the same year. Further, as can be seen in

Figure 2 (Percent of Reported Most Enjoyable Portion of the International Seminar for 2021 and 2022), more than 50.0 percent of students rated face-to-face intercultural communication as the most enjoyable part of the seminar in 2022, one of the ultimate goals of this International Seminar is to promote global citizenship in student participants’ by increasing their intercultural understanding and encouraging cross-cultural communication. Thus, this result indicates that the seminar programs’ expectations and students’ satisfaction levels match well in this area.

As for the group presentations held in 2021 and the UN (United Nations) General Assembly role-play in 2022, students rated higher for the UN role-play than group discussions. For example, one student, when reflecting on the event, stated that:

“Great! It was my first time at the MUN, and I think the event was a success and everyone worked hard to reach to a mutual conclusion. This motivated me to take part in further simulations like this one.”

Since the International Seminar was conducted online in 2021 during the COVID pandemic, due to its technical difficulties and limited virtual environments, the organizer decided not to implement the UN role-play in 2021. As a result, the final group presentations replaced the UN role-play as the concluding activity in the program. One of the disadvantages of holding an international seminar such as this online is that the event that requires high levels of interactions, discussions and negotiations, such as UN role-play, cannot be conducted virtually without difficulties. However, the final group presentations, which replaced the UN role-play in 2021, were still rated highly as one of the most enjoyable activities. Although the UN role-play could not be conducted this year, group presentations were successful in their online delivery, taking advantage of virtual techniques and creating videos using special effects, sounds and e-designs.

Though the immediate impression while observing the data indicates that overall satisfaction improved when students partook in the International Seminar conference in a face-to-face format, deeper investigation portrays the connection that portions of the event that emphasize intercultural communication and understanding are correlated to a higher level of satisfaction.

5. Conclusions

COVID-19 provides an opportunity to learn, rethink and reconfigure educational practices for a potentially more equitable, inclusive and accessible future that utilizes online learning teaching environments. These guidelines originate from the example of the seminar in Hiroshima, Japan, which held an international educational seminar serving a diverse student population during and after the pandemic. Drawing on students’ reflections on their efforts to cope and adjust to the pandemic can help educators understand, re-examine and redesign future educational seminars worldwide. Furthermore, these findings may facilitate future discussions on how best to create practical guidelines for asynchronous/synchronous virtual seminars. In adapting the seminar and study process to distance learning during the pandemic, the results of this study may imply that the teachers and organizers have executed it responsibly by preparing lectures and breaking up group sessions using many innovative learning elements and tools to approach the distance learning materials with high quality. While the online environment has progressed with new teaching tools and interactivity over time, these types of international seminars need to be constructed in a fashion where organizers and educators take advantage of various innovative tools and teaching styles online.

The limitation of this study was that the data collected in this study is limited to student participants’ perceptions and does not reflect the overall performance and outcomes of the International Seminar. Furthermore, quantitative analytical data is confined to the BEVI analysis—which assesses primarily the Belief, Values, Behaviors and Attitudes of the student participants. In order to assess the processes and outcomes of international, multicultural and transformative learning, we need to employ highly complex but measurable assessment tools in the future. Any credible assessment should require a sufficient understanding of relevant design, data and analysis by all program aspects. Further research on this topic needs to be undertaken before the association between online and face-to-face is more clearly understood. We recommend follow-up studies supplementing the comparative summary descriptive statistics with pre-post difference testing (e.g., MANOVA, paired-samples

t-test) and factor analysis to confirm the clusters of interrelated survey questions. More broadly research is also needed to determine if the results are applicable to other students populations and cultures around the world [

17].

Finally, higher education institutions around the globe are increasingly using the language of global citizenship to describe the skills they seek to cultivate in their students’ learning [

19,

20,

21,

22]. As the importance of international seminar programs ascends globally, we need to assess the outcomes thoroughly assess the outcomes and impacts of online learning and impacts of online learning more thoroughly and develop more effective and innovative international curricula.