Abstract

Influential and trusted opinion leaders play a crucial role in society, particularly in influencing the public about values and lifestyle aspects. However, studies that have explored the impact of opinion leaders on a sustainable lifestyle and Islamic values in a Muslim-majority country such as Malaysia are scarce. Hence, this present study investigated the moderating effect of opinion leaders on the relationship between Islamic values derived from Maqasid Shariah and a sustainable lifestyle in Malaysia. The two methods deployed in this study were survey and in-depth interviews. Data retrieved from 682 questionnaires completed by Malaysian respondents were analysed using Smart PLS. The outcomes showed that, among the five proposed hypotheses, only one was accepted—the moderating effect of opinion leaders on the relationship between preserving intellect and a sustainable lifestyle. In-depth interview sessions were held with 18 respondents encompassing Islamic figures, environmentalists, and survey respondents. Most respondents claimed that the role of opinion leaders is important, and a healthy mind (preserving intellect) should be the priority to achieve a sustainable lifestyle. The study outcomes may serve as a reference for the Malaysian government to devise effective plans for sustainable lifestyle education by incorporating the Islamic framework.

1. Introduction

Human actions have contributed to climate change, environmental degradation, health issues, and economic crises, actions that are hazardous to humans [1,2,3]. To make matters worse, this decline in environmental quality has been linked with an increase in the global human population [4] and a rise in destructive natural calamities [5]. Despite countless efforts to overcome these issues, to several Asian countries, such as China and India, environmental issues have become a serious threat to both humankind and nature [6]. Malaysia is no exception, as the country recorded severe pollution issues that caused its Environmental Performance Index (EPI) to decline in 2020 [7]. The alarming environmental issues across the globe have garnered much attention and sparked heated debates due to their heavy impact on sustainability [5]. People have also become more aware of critical environmental issues, particularly regarding the adverse impacts of global warming and pollution on our planet Earth [3].

Malaysia is a Muslim-majority country. Islam, therefore, has a strong influence on the majority of the Malay Muslim populace, in particular concerning their attire and food consumption (deemed “halal”), to name a few [8]. Further evidence of Islam’s overarching influence can be seen in the environmental reporting in Malay newspapers, which has been influenced by Islamic values, particularly the Tawhid (unity of God) and Iman (faith) values [9]. Islamic values upheld by Maqasid Shariah consist of the following five goals: preserving religion, life, progeny, intellect, and wealth. It is noteworthy to mention that the Muslims in Malaysia prioritise and comply with the Shariah principles that revolve around these five goals [10]. The underlying principles of Maqasid Shariah that emphasise harmonious living and protection of all align particularly well with the Malaysian context because the majority of Muslims here reside alongside people of different faiths, including Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity, and many more [11]. Simply put, Maqasid Shariah ascertains the well-being and welfare of people from all walks of life [12].

The evidenced impact of Maqasid Shariah on a sustainable lifestyle is in line with the theory of goal setting that emphasises the regulation of human behaviour based on the following three goals [13]: hedonism, gain, and normative goals. The theory postulates that goals can influence one’s knowledge, attitude, evaluation, and behaviour [14]. Thus, with the primary goal of preserving religion, life, progeny, intellect, and wealth under Maqasid Shariah, one is deemed to live sustainably in a society.

The role of opinion leaders, who are trusted and reliable individuals to a person or in a community to help in decision-making [15] (e.g., media, friends, family, government, celebrities, leaders, and non-governmental organisation), is imminent in establishing the relationship between the five goals of Maqasid Shariah and a sustainable lifestyle. Opinion leaders are more observant and aware of the trends and changes in any society, thus exerting more influence on encouraging people to embrace changes towards the betterment of their lives [16], including achieving a sustainable lifestyle. In the case of Malaysia, its government agencies, such as the Department of Islamic Development Malaysia (JAKIM), play a significant role as opinion leaders by amplifying the importance of living a sustainable lifestyle in adherence to the Maqasid Shariah goals, which cover, for instance, governance and education. Influential figures in society, such as Islamic leaders, also use social media platforms to convey the link between a sustainable lifestyle and Islam through the lens of the goals of Maqasid Shariah, as social media is effective at encouraging the masses to adopt environmental sustainability as their lifestyle [17].

Many studies view opinion leaders as an influential social factor [18]. In the context of Malaysia, refs. [9,15,19,20] investigated the role of opinion leaders, but omitted its link to sustainable lifestyles. While many studies have examined the effect of Maqasid Shariah in the area of social sciences [21] within the context of Malaysia, an equally high number of scholars have explored the perspectives of Maqasid Shariah, such as [22,23,24]. As their studies have mostly concentrated on the economy, business, and banking segments, this present study addressed this gap by assessing the moderating role of opinion leaders on the relationship between the goals of Maqasid Shariah and a sustainable lifestyle in Malaysia.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Lifestyles

In general terms, lifestyle refers to the unique ways in which a group or social community lives, thus addressing the question of “how to live” [25]. As a counterpoint to the prevailing unsustainable lifestyles, the very concept of a sustainable lifestyle was initiated along with the inception of sustainable development [26]. The primary principle of a sustainable lifestyle is reflected in the adoption of the “5R” framework, which revolves around reducing, re-evaluating, reusing, recycling, and rescuing [25].

A wide range of definitions of sustainable lifestyles is available. For instance, a sustainable lifestyle was defined by [25,27,28] as a cluster of habits and patterns of behaviour embedded in society and facilitated by institutions, norms, and infrastructures that minimise the use of natural resources and reduce the generation of waste while promoting fairness and prosperity for all.

The United Nations Environment Programme [29] highlighted the absence of a universal definition for a sustainable lifestyle, but rather “sustainable lifestyles” due to it being an intricate concept that reflects the cultural, economic, and social heritage of various societies. In the Muslim societies that uphold Maqasid Shariah, for instance, a sustainable lifestyle denotes the patterns of behaviour, habits, and practices guided and directed by the five goals of Shariah, while being facilitated by institutions and infrastructures to ensure a balance between ecological limits and the well-being of the people [21,30,31].

Instances of studies and projects that were undertaken to promote sustainable lifestyles were outlined in SPREAD Sustainable Lifestyles 2050 in Europe and Lifestyles of Health and Sustainability (LOHAS) in North America [32,33]. Since frameworks of sustainable lifestyles in the Asian context are scarce [34], the definition of a sustainable lifestyle in this context is vague and heavily reliant on the Western perspective.

2.2. Maqasid Shariah

Maqasid Shariah signifies the objectives or goals of Islamic law [35,36]. The goals are classified into the following three major groups, with each group consisting of sub-objectives or goals: the necessary goals, the needed goals, and the embellishment goals [35,37]. There is a dearth in the literature regarding the need and the embellishment goals, ascribable to the lower importance given to these two goals when compared to the necessary goals, which have garnered more attention among scholars. The five necessary goals are preserving religion, life, intellect, progeny, and wealth. Imminently, Maqasid Shariah has been adopted as a framework of ultimate reality and ethical guidance adhered to by many prominent Muslim scholars such as Al-Juwayni (d.1085 A.D), Al-Ghazali (d.1111 A.D), and Al-Shātibī (d.1388 A.D) due to its derivation from the revelation (i.e., the Holy Quran and the teachings of Prophet Muhamad (PBUH)) [38,39]. Endowed with a spiritual nature, Maqasid Shariah offers a broad perspective for comprehending and acting both ethically and morally with other human beings and the rest of the Almighty’s wonderful creations [39].

Some recent studies have examined the impact of goals on guiding and framing human behaviour within the environment and sustainability fields. For instance, the theory of planned behaviour has been extended by incorporating goals as significant drivers for human behaviour [40,41]. A newly proposed theory called the “goal framing theory” views goals as crucial determinants that can influence human behaviour [42]. Essentially, numerous studies have examined the effect of goals on human behaviour. For example, Reference [43] demonstrated that goals can predict sustainable behaviour. Similarly, Trask et al. [44] proved the effect of goals in directing human actions.

Despite the vast discussions on the five goals of Shariah, which cover various issues including environmental and sustainability issues, they were mostly skewed towards the normative (classical scientific method) approach, while empirical studies that examined the five Shariah goals as predictors are scarce, such as those carried out by [45,46]. As such, this present study assessed the five goals of Shariah empirically to predict sustainable behaviour (sustainable lifestyle) in Malaysia.

2.3. Opinion Leaders

Since the initiation of the two-step communication theory in the 1940s by Lazarsfeld, Berelson, and Gaudes, the concept of opinion leaders has attracted increased scholarly attention, with numerous studies from various disciplines having explored the impact of opinion leaders. Past studies have conceptualised opinion leaders in various settings and contexts [47,48]. First, opinion leaders have been defined as those who exercise influence over decisions made by others [49]. Meanwhile, Parau et al. [48] defined opinion leaders as those who heavily influence their network and the opinions of individuals connected to them. In the field of behaviour related to the environment and sustainability, opinion leaders are defined as those who inspire and mobilise others towards achieving purposeful change(s) [50]. Involving opinion leaders in the field of the environment and sustainability promotes changes in personal behaviour, such as being encouraged to use public transportation, to save water and energy, and to recycle, to name a few [51].

The vast literature has highlighted a wide range of terms and types of opinion leaders, including opinion leaders/leadership, influential leaders/users, influencers, influential nodes, block leaders, and many more [47]. While examining the controversy surrounding the distinction between opinion leaders and influencers, Bamakan et al. [47] outlined several types of opinion leaders, such as local–global opinion leaders, monomorphic–polymorphic opinion leaders, positive–destructive opinion leaders, and long–short-term opinion leaders. The literature distinguishes opinion leaders from opinion seekers [52] and high-level opinion leaders from low-level ones [53,54].

Information conveyance by opinion leaders [55] denotes a mediating role. Information is transmitted more effectively when conveyed by people from a similar social network [18]. Recent scholars have examined opinion leaders as a moderator to explore their moderating impact. Kim et al. [56], for example, assessed opinion leaders as a moderator on the relationship between five independent variables and a dependent variable. Next, Flores-Zamora & García-Madariaga [54] explored the impact of opinion leaders on the correlation between service attributes and loyalty.

3. Theoretical Framework

Both Maqasid Sharia Theory (MST) and opinion leaders were deployed as the background and guidance in this present study. First, the goals of Maqasid Shariah and their impact on human behaviour reflect an ancient notion that goes back to d.478/1085 [30]. Although many studies have looked into MST (see [30,57,58]), most of them are normative (classical scientific method) in nature [46]. According to [59], normative studies identify and inform/persuade people to execute behaviour based on a set of norms or values. The approach assumes clear and robust relationships among variables (cause and effect) [60]. Meanwhile, empirical studies rely on empirical evidence [60], an approach that recent scholars have begun to employ in investigating the aspects of MST (see [45,46,61,62,63]).

Etymologically, Maqasid Shariah outlines intents and goals [30]. The manifestation of the goals stipulated in Shariah benefits humankind [64]. Theoretically, MST is built upon a rational and goal-oriented basis [30]. Prior studies (see [40,41,43,65]) exemplified the role of goals in motivating and directing one’s behaviour in multiple settings [41], including the environment and sustainability domains (sustainable behaviour) [14].

As discussed earlier, MST comprises three major goal categories, namely necessities, needs, and embellishment goals [57]. The first category of MST goals, the necessary goals, was explored in this present study. These goals include the preserving of religion, life, intellect, progeny, and wealth. MST postulates that striving to attain these goals could affect one’s behaviour towards achieving positive well-being [30]. The study of these goals has attracted the attention of scholars from both the Muslim world and beyond. However, as elaborated earlier, most of those studies are normative with only a handful of empirical research work.

Second, the idea of opinion leaders stemming from the two-step flow of communication theory upholds that personal influence exercised by others can affect one’s attitude and actions more than information gained from other communication channels (e.g., media) [49,55]. An opinion leader denotes one’s desire to influence the opinion, attitude, decision, or behaviour of others and/or to be the person others turn to for advice due to a situation or issue [66]. The influence of opinion leaders may serve as role models for others [51,53,67].

Opinion leaders can shape or change human behaviour [50]. As people differ in terms of their desire to be opinion leaders [66], they are classified into high- and low-level opinion leaders [54,66]. High-level opinion leaders engage with others to resolve issues and behaviour related to the environment and sustainability [51,53,66,68]. Geiger et al. [68], for instance, disclosed that those well connected with opinion leaders preferred engaging in pro-environmental behaviour.

Based on the two-step flow theory that opinion leaders are placed between sender and receivers, they have a mediating role as they gain information from reliable sources and convey it to the audience [68]. Recent scholars have introduced opinion leaders as a moderator to facilitate the impact of independent variables on a dependent variable (or dependent variables) [53,54,66,67,69]. Seebauer [67] defined the moderator variable of opinion leaders as a general status of social renown and competence deriving from earlier events and interactions.

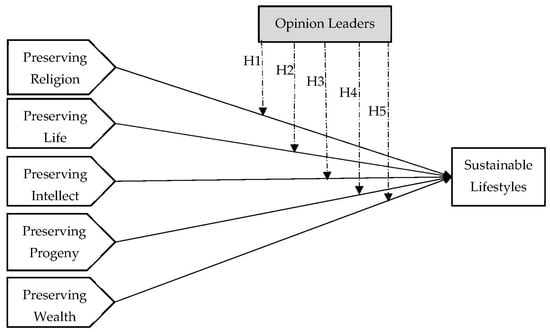

Based on the discussion above, this study assessed the moderating effect of opinion leaders on the relationships between the five goals of Shariah and a sustainable lifestyle in Malaysia. A list of hypotheses was formulated based on the research framework to meet the study’s objectives (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The proposed theoretical framework. Note: The dotted paths indicate the moderating impact.

4. Moderation Hypotheses

Past studies have extensively investigated the social influence of opinion leaders in the psychology research domain [18,70]. Numerous studies have examined opinion leaders as a mediating variable for transmitting the influence of other personal drivers [67]. As depicted earlier, only a handful of studies have deployed opinion leaders as a moderator [54]. For instance, Seebauer [67] claimed that opinion leaders serve as a gatekeeper to facilitate the impact of other drivers. Similarly, Skoric & Zhang [69] applied opinion leaders as the moderator variable in the relationships between news media and environmental knowledge and environmental engagement, as well as the correlations of Weibo use with environmental knowledge and environmental engagement. Kim et al.; Skoric & Zhang; Viswanathan et al. [56,69,70] distinguished high-level opinion leaders from low-level opinion leaders. Likewise, Flores-Zamora & García-Madariaga [54] deployed opinion leaders as the moderator variable in the relationships between service attributes (satisfaction and perceived quality) and loyalty intention. They further differentiated high-level from low-level opinion leaders. Based on the above statements, the following hypotheses are thus proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The relationship between preserving religion and sustainable lifestyles will be stronger when the individuals have a high level of opinion leadership.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The relationship between preserving life and sustainable lifestyles will be stronger when the individuals have a high level of opinion leadership.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The relationship between preserving intellect and sustainable lifestyles will be stronger when the individuals have a high level of opinion leadership.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The relationship between preserving progeny and sustainable lifestyles will be stronger when the individuals have a high level of opinion leadership.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

The relationship between preserving wealth and sustainable lifestyles will be stronger when the individuals have a high level of opinion leadership.

5. Materials and Methods

Two methods were deployed in this study: survey and in-depth interview. Initially, a survey was carried out in six Malaysian states.

5.1. Sample Size

In order to select a representative sample of the entire Malaysian population, the multistage stratified random sampling technique described by [71] was executed. Referring to the Malaysian Department of Statistics [72], the sample was divided into three strata: high, medium, and low urbanisation rates. Two states were selected to represent each stratum, as follows: Selangor (Klang Valley) and Penang to represent the high urbanisation rate, Johor and Terengganu for the medium urbanisation rate, while Sarawak and Kelantan to signify the low urbanisation rate. The G*power 3.1 software was used to identify the required sample size for this study. The result showed that a sample size of 153 respondents was required. However, following the “more is better” rule, a sample size of 682 respondents was used.

5.2. Instruments

The questionnaire comprised several sections (see Appendix A), including the first section, which gathered demographic data from the respondents, such as gender, marital status, age, religion, ethnicity, education, monthly income, and resident state. The survey questionnaire, which was developed based on past studies, consisted of items relevant to the study objectives. In total, 31 items (independent variables) were adapted from [63] to measure the five Shariah goals. Next, the dependent variable (sustainable lifestyle) was measured by using seven items retrieved from [73], whereas the moderator variable (opinion leaders) was measured based on five items obtained from [51]. A five-point Likert scale was deployed for the questionnaire with anchors ranging from 1 (totally disagree/never) to 5 (totally agree/always). The five items used to measure the opinion leaders also employed the five-point Likert with slight changes (i.e., never/very often, give very little information/give a great deal of information, not at all likely to be asked/very likely to be asked, and not used as a source of advice/often used as a source of advice). Hence, respondents that scored three and above (i.e., the mean value) were considered as having high leadership, and vice versa [74].

The questionnaire was developed in both Malay (the national language used in Malaysia) and English. In order to ensure translation accuracy, consistency in meaning, and coherence, the back-to-back translation technique was carried out. The dual-language survey enabled the respondents to provide responses in the language of their choice. The first page of the questionnaire states the details of the survey and captures consent from the respondents to participate in the survey voluntarily [75]. Upon adhering to the ethical requirement, apart from gaining consent from the respondents to participate in the survey, their identity was protected by using identification codes, and private information (i.e., the respondent’s name) was not collected during the survey [76]. The ethical aspect of the survey was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of USM (USM/JEPeM/21040327).

5.3. Data Collection

Prior to questionnaire distribution, the items were revised by a panel of two experts in the related field to evaluate and provide feedback on the clarity of the item wordings and the relevance of items incorporated into the questionnaire [71]. A pilot test with 50 respondents was conducted. The outcomes derived from the pilot survey revealed that the questionnaire was clear and comprehensible, thus attesting to its reliability and validity for data collection. As for the actual survey, which was collected through a face-to-face questionnaire, 682 completed questionnaires were gathered from Malaysian citizens between October 2021 and July 2022 in six states comprising urban and rural areas.

5.4. Data Analysis

SPSS Version 25 was deployed in this study for inferential (descriptive) analysis. The Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) method was applied to test the research hypotheses, while the conceptual model was evaluated using SmartPLS 3.0. SmartPLS was selected due to its ability to manage low sample sizes, data that lack normality, and an intricate structural model with many constructs, indicators, and model correlations [77]. Two model assessments were considered in the analysis when using SmartPLS: measurement model assessment (outer model) and structural model (inner model).

Table 1 lists the demographic data of the respondents. Among them, 44.6% were men and 55.4% were women. Overall, 43.4% of them were married and 56.0% were not. Most of the respondents (49%) were 21–30 years old. In total, 69.8% of the respondents were Malays and 72.4% were Muslims. Most of the respondents (59%) had a college or university education. The majority of the respondents earned less than RM2000 (28.6%).

Table 1.

Demographic profile of the respondents.

Phase 2 of this study involved in-depth interview sessions with selected respondents to capture more information regarding the role of opinion leaders in influencing the relationships between the five goals of Shariah and a sustainable lifestyle. Referring to [78] pertaining to the benefits of employing the mixed method approach, in-depth interviews allowed for a thorough examination of one’s point of view regarding religion and its relation to the target behaviour. The purposeful selection of the respondents for the in-depth interviews ascertained their applicability. Six interviewees from each group of the three sub-groups (i.e., key Islamic figures, environmentalists, and survey respondents) (18 respondents) were interviewed using the data saturation technique.

Six of the eighteen respondents were female, and the remaining twelve were male. The age of the respondents ranged between 25 and 56 years old. The respondents were also ethnically and religiously diverse: Malay Muslims (N = 14), Hindus (N = 3), and Chinese Christian (N = 1). Most of the respondents (N = 7) possessed a Bachelor’s degree in a vast range of subjects, including communication, human development, Islamic studies, production, and animal health. The interview respondents held a variety of professions, including mufti and deputy mufti, director, president, and officer.

In order to protect respondent anonymity, the interview sessions were conducted by adhering to the guidelines provided by the Human Research Ethics Committee of USM (USM/JEPeM/21040327). In maintaining secrecy, each interviewee was given an identity code, such as ID1 and ID2. The medium of language used during the interview sessions was determined by the respondents based on their preference: English, Malay, or a combination of both languages. The interviews were audio recorded with the consent given by the respondents. Njølstad et al. [79] prescribed that each interview session be performed between 20 and 40 min in a quiet room at the respondents’ workplace. The interview protocol was guided and developed based on the survey result. The MAXQDA software was then applied to analyse (i.e., coding, themes) the interview outcomes. To analyse the result of the interviews, Braun and Clarke’s (2006) thematic analysis framework was used as a guideline to initiate the codes and themes.

6. Results

6.1. Survey Results

In order to estimate the models using Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), two major steps were executed—the estimation of the measurement and structural models. The measurement model represents the relationships between each construct and the related indicators, whereas the structural model represents the structural paths among the constructs [80]. The structural equation modelling was determined as the best technique to comprehend more complex relationships due to its application of more sophisticated multivariate data analysis methods [81].

6.1.1. Measurement Model

Several steps were provided by [77] to assess the measurement model (or reflective measurement model). The initial step was to determine the indicator loadings. As a rule of thumb, loadings above 0.708 are recommended [77]. Second, internal consistency reliability was determined based on Composite Reliability (CR) and/or Cronbach’s alpha. If the values of CR or Cronbach’s alpha fall between 0.60 and 0.70, the result is acceptable, whereas values from 0.70 to 0.90 indicate satisfactory to good results [81]. Researchers should be cautious if the values recorded are 0.95 and above [81]. Third, it is vital to address convergent validity, which denotes the extent to which the construct converges to explain the variance of its items. Convergent validity can be determined via the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for all items on each construct. The acceptable value of the AVE is 0.50 or above [77]. The fourth step is to check discriminant validity to ensure that the constructs in the model are empirically distinct from each other. Fornell–Larcker and the Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) are the common tests applied to determine discriminant validity. The HTMT is preferred due to its superior performance. To establish discriminant validity, the HTMT values should not exceed 0.90 [77]. In addition, Fornell–Larcker assessment also shows that there is no issue with the discriminant validity, where the value for the square root of the AVE of each construct compared with all correlation values in the same column should be higher than the other values [81]. To conclude, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 indicate the absence of any issues with the measurement model of this study.

Table 2.

Reliability and validity analyses.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity, Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT).

Table 4.

Fornell–Larcker.

Prior to proceeding with further analysis to examine the structural relationships, it is important to address the issue of collinearity, as recommended by [77]. Table 5 presents the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values for all constructs, indicating their level of collinearity. The results demonstrated that all VIF values were below 3, aligning with the guidelines provided by [77]. Therefore, collinearity was not a concern in this study, ensuring the regression results were not biased by this factor.

Table 5.

Inner VIF values.

6.1.2. Structural Model

After ensuring that the measurement model has achieved a satisfactory level, the next step in assessing the PLS-SEM results involved the assessment of the structural model. Upon estimating the structural model, R2 is a crucial criterion that should be determined especially when addressing the moderating effect in a model [74]. The R2 signifies the extent to which the exogenous constructs (preserving religion, preserving life, preserving intellect, preserving progeny, preserving wealth, and opinion leaders) explain the endogenous construct (sustainable lifestyle). The orthogonalising approach with mean-centred (to differentiate between high and low leadership) was deployed to perform the moderation analysis. The finding revealed an increase in R2 after incorporating the moderating effect. The R2, which showed a value of 0.436 before including the moderating effect, increased to 0.442 when the moderating effect was incorporated. The related guideline depicts 0.25 as weak, 0.50 as moderate and 0.75 as substantial [77]. Hence, the R2 value in this study indicated a weak value. Next, ƒ2 (effect size) is another crucial criterion used to determine the moderating effect [82] and is calculated as:

Based on the guideline, ƒ2 values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35, respectively, denote small, medium, and large effects [83]. By deploying the above formula (the Effect Size Calculator or SmartPLS), the ƒ2 value was 0.01—below the value listed in the guideline. Nonetheless, based on the guideline proposed by [84], 0.005, 0.01, and 0.025 represent small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively. Hence, the effect size related to the moderating effect deployed in this study was medium. It is noteworthy to mention that the effect size of ƒ2 in this study contributed 1% to R2 as a function of the moderator.

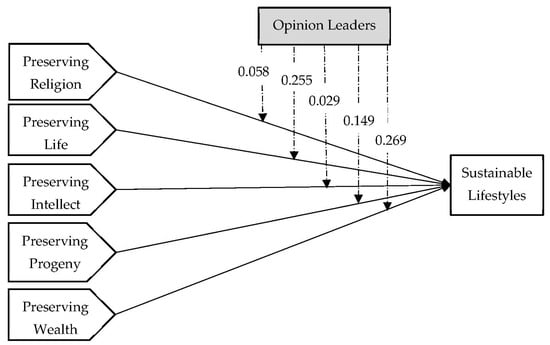

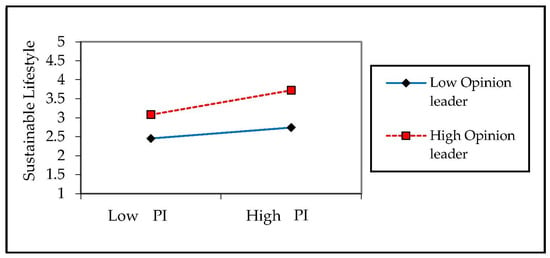

The beta coefficient for the interaction effect of Preserving Intellect (PI)*Opinion Leader (OL) was positive at 0.089 and statistically significant (p < 0.5) (see Table 6 and Figure 2). This showed that the relationship between preserving intellect and sustainable lifestyle was stronger for influential/high-level opinion leaders (see Figure 3). Thus, only H3 was accepted among the five hypotheses.

Table 6.

The results of moderation interaction.

Figure 2.

Final model with p-values.

Figure 3.

The interaction between preserving intellect and opinion leaders in predicting a sustainable lifestyle.

Figure 3 illustrates the moderating effect of opinion leaders on the relationship between preserving intellect and a sustainable lifestyle. This correlation turned stronger/weaker when the level of the opinion leaders was high/low.

6.2. Interview Results

Notably, two important themes emerged from the interviews, as elaborated in the following:

- The strong influence of opinion leaders:

Most of the interviewees described that opinion leaders have a strong impact on influencing people’s comprehension of the connection between Maqasid Shariah and a sustainable lifestyle. As opinion leaders are famous figures in a society with a sizeable number of followers and fans, they can easily influence the masses’ understanding regarding a concept or an idea. According to one of the respondents:

“Because… in Malaysia… For example, Ustaz Azhar Idrus can go up, because many people follow him. Why Ustaz Kazim can do this, because there are people with him. So, actually that’s a really good opportunity. Can make people to get exposure about the environment (Maqasid Shariah and sustainable lifestyle), and maybe when they share it with the public, they feel interested and curios about it”.(ID 6)

Some interviewees claimed that opinion leaders, such as Islamic figures, are important and prominent figures in society. Therefore, their influence on the relationship between Maqasid Shariah and a sustainable lifestyle should be significant:

“Hmmm… Because I have my view… it doesn’t matter whether it’s imam, bilal, mufti or religious teacher… They are the reference, especially if it involves matters related to religion. When they mention Maqasid Shariah (and sustainable lifestyles), it will be clear to the community and they will follow it”.(ID 15)

- 2.

- The importance of keeping a healthy mind:

Many interviewees asserted that the role of opinion leaders is obvious in influencing the relationship between preserving intellect and a sustainable lifestyle attributable to the importance of having a healthy mind, as it is the key to human action and healthy well-being. A healthy mind that is free from drugs and other addictive substances enables one to think wisely and live sustainably. As several respondents put it:

“The mind is like the CPU of a computer right, when the CPU is damaged, the computer does not work. That makes sense, right? What if we don’t take care of our minds, how can we live sustainably? How do we want to think… we want… we want a house, we want to clean the house, he… if… if we are in a state of drunkenness or take drugs for example… because all that is forbidden? If the mind is no longer… no longer able to function perfectly, life is not sustainable. Ha, obviously it can’t be sustainable”.(ID 16)

“If the mind is messed up as an example of a drug addict, I’m one hundred percent sure he won’t care about sustainability. The addict sits under the bridge; he will pollute the river, the environment, and the air”.(ID 12)

7. Discussion

This study assessed the moderating effect of opinion leaders on the relationships between the five goals Maqasid Shariah and a sustainable lifestyle. This empirical study bridged a critical gap by contributing knowledge to the scarce literature on Maqasid Shariah, a sustainable lifestyle, and sustainable behaviour. Past studies on the impact of Maqasid Shariah were mostly normative [46] or focused on phenomena apart from sustainable behaviour and a sustainable lifestyle. Only a handful of empirical studies have examined different phenomena using Maqasid Shariah as a predictor. For instance, Reference [45] assessed the influence of Maqasid Shariah on the well-being of humans, while [62,84] evaluated its impact on quality of life. As such, extensive empirical studies are sought to examine the relationships among Maqasid Shariah, a sustainable lifestyle, and behaviour.

As opposed to the theory of opinion leaders that stipulates the role of opinion leaders as significant, the empirical outcomes of this study on the moderating impact of opinion leaders revealed some setbacks of the ability of opinion leaders to exert influence on the relationships between Islamic values (Maqasid Shariah) and a sustainable lifestyle in Malaysia. Referring to Table 6, only H3 (the moderating impact of opinion leaders on the relationship between preserving intellect and a sustainable lifestyle) was supported, while the remaining four hypotheses were rejected. Turning to the interview sessions, most of the interviewees asserted that the influence of opinion leaders was more prominent in connecting a sustainable lifestyle and preserving intellect, ascribable to the human mind as the key to life. Simply put, a healthy and positive mind is imminent for people to embrace a sustainable lifestyle. Similarly, Fajzi & Erdei [85] reported on the importance of sustaining mental health because human psychology and the mind are the two integral components in practicing a sustainable lifestyle.

Notably, this study disclosed the insignificant role of opinion leaders in the relationships of preserving religion, life, wealth, and progeny with sustainable lifestyles. In line with these outcomes, Yosua et al. [86] found that the weak influence of opinion leaders stemmed from the divergence in the views between opinion leaders and the public in terms of social status, wealth, skills, and even social distance. The influence of opinion leaders could be limited within a specific community that dismisses adherence to conventional values [86]. In another study, Geiger et al. [68] claimed that the weak influence of opinion leaders is attributed to the fear that lurks among them of being perceived negatively, stemming from their unsolicited advice given to the audience.

Past studies (see [54,69]) unveiled a variance between high-level and low-level opinion leadership. Referring to the interaction plot illustrated in Figure 3, no significant difference was noted between high-level and low-level opinion leaders in influencing the relationship between preserving intellect and a sustainable lifestyle in Malaysia. In a different context, Viswanathan et al. [70] also revealed that the changes in the level of opinion leaders did not display any strong moderating effect. They added that individuals with high-level opinion leadership were more successful in drawing new customers when compared to those with low-level opinion leadership.

The moderating effect obtained in this study was at a medium level (0.01). It is noteworthy to assert that, depending on the context of a study, the reported outcomes may still be meaningful, especially if there is a meaningful change in the path coefficient [74]. In a similar vein, the results of this present study still supported the outcomes of prior investigations pertaining to the impact of opinion leaders on promoting a sustainable lifestyle [68]. As such, future studies should delve into different contexts by deploying a similar or other relevant measurement that might validate and complement the results reported in this study. For instance, Flores-Zamora & García-Madariaga [54] highlighted that opinion leaders can change their role across groups or lifecycles. In fact, more studies should assess the moderating effect of opinion leaders using, for example, a 7-point Likert scale rather than a 5-point one [82] or Multi-Group Analysis (MGA) by dividing the opinion leaders into two groups (high and low levels).

Due to the scarcity of studies exploring the influence of opinion leaders as a moderator variable, particularly within the behavioural research domain related to the environment and sustainability, several researchers, such as [68], have called for the expansion of the goal-directed influence of opinion leaders among communities. The opinion leaders in Malaysia, including the government (i.e., JAKIM) and Islamic figures, need to be more proactive in their role of communicating a sustainable lifestyle through the lens of Islam, particularly based on the five goals of Maqasid Shariah. Similarly, most of the interviewees strongly believed that opinion leaders exert a heavy impact on influencing Malaysians mainly because they are famous figures with a significant number of followers and are considered reference points by the community. Hence, it is imminent for opinion leaders, especially the famous and prominent ones, to educate the society about a sustainable lifestyle that is aligned with Islam via social media. Along that line, Al-Mulla et al. [87] claimed that the social media platform has a great persuasive role in educating about sustainable living and cultivating sustainable behaviour.

8. Implications

This study’s focus was mainly on the role of opinion leaders and their influence on the relationship between the five goals of Shariah and sustainable lifestyles in Malaysia. The implication of intervention variables (moderators) is a common strategy within behavioural and communication studies [88,89]. Opinion leaders are part of a human-based and informational intervention strategy in directing, strengthening, or weakening the relationship between independent variables (e.g., the five goals of Shariah) and the dependent variable (sustainable lifestyles).

Theoretically, the result of this study supported and contributed to the implication of the concept of opinion leaders as a moderator, which was initially applied as mediators to disseminate information, especially new ideas from the sender (typically media) to the receivers (two-step flow) [49]. Hence, those ideas will be adopted in society.

In addition, the study result contributed to the traditional literature of opinion leaders (i.e., opinion leaders and opinion seekers) by emphasising the possibility of dividing the opinion leader into high opinion leaders and low opinion leaders depending on their leadership level.

Practically, the findings of this study provide insight for the authorities to consider the role of opinion leaders in elevating individuals’ awareness about how Shariah’s values can help them to practice a more sustainable approach in life. Meanwhile, opinion leaders, especially key religious or environmentalist figures, should work closely with government or non-government organisations to disseminate information on sustainable lifestyles to the public. In addition, opinion leaders should be aware of effective communication strategies and take advantage of the available communication means (e.g., mass media, social media) to send messages that can influence individuals to change their unsustainable lifestyles to more sustainable ones.

9. Conclusions

This study explored the role of opinion leaders as a moderator variable in the link between the five goals of Maqasid Shariah and a sustainable lifestyle within the context of Malaysia. Among the five goals of Maqasid Shariah, the moderating role of opinion leaders was found to be strong in the correlation between preserving intellect and a sustainable lifestyle. On the contrary, the theory of opinion leaders, in particular on their role as prominent figures within a society, was upheld. This was especially true among individuals with high-level opinion leadership, such as government authorities. Therefore, it is important to recognise and empower the role of opinion leaders in environmental and sustainability communication matters such as a sustainable lifestyle.

The study outcomes indicated significant implications. First, the results may serve as an effective reference for the Malaysian government, such as JAKIM, to strategise their education plan by embedding Islamic values and a sustainable lifestyle. This is viewed as an integral step because it educates the community residing in Malaysia to preserve religion, life, intellect, progeny, and wealth in achieving a sustainable lifestyle. Since the role of opinion leaders emerged as insignificant in this study, it is imminent for opinion leaders (e.g., JAKIM, Islamic leaders and preachers, social media influencers, etc.) to be more proactive in their actions concerning the topic at hand. Finally, yet importantly, the study outcomes are beneficial to other Islamic countries, especially Indonesia and Brunei.

Future studies in this area should look into the specific role of a particular opinion leader (e.g., social media influencer) and investigate the varying findings, if any. As prescribed by [82], a seven-point Likert scale should be deployed to measure the moderating variable within the context of Malaysia or other similar collectivistic cultures. Moreover, careful attention should be paid to the distribution of the respondents in order to be able to generalise the result. In addition, future researchers could also explore other Islamic countries’ experiences, as not all Islamic societies are heterogenous like Malaysia. As there are more than 50 Muslim countries in the world, it is deemed important for Islamic values to be applied in the practices of a sustainable lifestyle for the populace.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.S.M.S.; methodology, M.S.M.S., A.M. and B.O.; formal analysis, A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.M.S. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, M.S.M.S.; supervision, M.S.M.S. and B.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors thank the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia for the funding support of this research under the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) with Project Code FRGS/1/2021/SSI03/USM/02/2.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Section 1: Demographic section

1. Gender: □Male □Female

2. Marital status: □Unmarried □Married

3. Age: □18~20 □21~30 □31~40 □41~50 □51~59 □60 and above

4. Religion: □Islam □Buddhism □Christianity □Hinduism □No religion

□Other, please state_____________

5. Ethnicity □Malay □Chinese □Indian □Other, please state____________

6. Educational level: □ Primary school □Secondary School

□University or college □Graduate School

7. Monthly income (RM): □No income □less than 2000 □2001~2498 □2499~4849

□4850~10,959 □10,960~15,039 □ More than 15,040

8. In which state do you live?

□Johor □Kelantan □Pulau Pinang □Selangor □Terengganu □Sarawak

Section 2: About Life objectives

The statements below are related to some aspects of your life. Think in terms of your everyday experiences and please tick the most appropriate response.

Preserving religion items

- Religion provides me guidance in my life.

- Believing in God is essential for life.

- I perform prayers regularly.

- I believe in the Divine will and decree.

- I allocate enough time to learn about religion.

Preserving life items

- I get enough food.

- I have adequate clothing.

- I live in comfortable house.

- I am living a moral life.

- I have good relations with family and relatives.

- I live in peaceful neighbourhood.

- I am adopting a healthy lifestyle.

- I have access to health facilities.

- I have good relations with neighbours.

Preserving intellect items

- I can operate a computer.

- I allocate enough time for reading.

- I had adequate nutrition during the growing age.

- I attend programs/courses to improve knowledge.

- I contribute my views in discussion regarding matters of everyday life.

Preserving progeny items

- Offspring should be provided with basic education.

- Offspring should be provided with moral education.

- Offspring should be protected from involvement in juvenile delinquencies.

- Children should have the necessary immunization.

- Children’s behaviour and activities should be monitored.

- It is my responsibility to ensure a healthy environment.

- Children should enjoy basic human rights.

Preserving wealth items

- I can manage my own and family finances.

- I save part of my earnings

- I have stable income.

- I have sufficient income.

- I have financial investments.

Section 3: About Lifestyle

The following are statements about your lifestyle on a daily basis which is represented by your behaviour. Please tick the most appropriate response that most represent your degree of actual behaviour.

- I opt for energy efficient appliances (e.g., choosing appliances with energy efficient rating (EER) labels).

- I attend seminars, workshops, conferences or exhibitions concerning the environment.

- I purchase products that can be recycled.

- I participate in environmental activities organized by institutions or organizations (e.g., tree planting activity, beach clean ups).

- I practice recycling in my household.

- I make decisions more consciously in effort to avoid over consumption.

- I advise others (i.e., family, friends) to reduce consumption of resources (e.g., water, electricity).

Section 4: About your interaction with others

Please rate yourself on the following scales relative to your interaction with friends and neighbors regarding sustainable lifestyles.

- In general, do you talk to your friends and neighbours about sustainable lifestyles?

- When you talk to your friends and neighbours about sustainable lifestyles, do you

- During the past 6 months, how many people have you talked to about sustainable lifestyles?

- Compared with your circle of friends, how likely are you to be asked about sustainable lifestyles?

- Overall in all of your discussions with friends and neighbours, are you.

Note: all the above items were measured with the five-point Likert scale with anchors ranging from 1 (totally disagree/never) to 5 (totally agree/always).

References

- Hiratsuka, J.; Perlaviciute, G.; Steg, L. Testing VBN theory in Japan: Relationships between values, beliefs, norms, and acceptability and expected effects of a car pricing policy. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 53, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.; Smith, C. Towards Sustainable Lifestyles. In The Cambridge Handbook of Psychology and Economic Behaviour, 2nd ed.; Lewis, A., Ed.; Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 481–515. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Wen, Z.; Feng, F.; Zou, H.; Fu, C.; Chen, L.; Shu, Y.; Sun, C. An online survey of the attitude and willingness of Chinese adults to receive COVID-19 vaccination. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 2279–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadegaridehkordi, E.; Foroughi, B.; Iranmanesh, M.; Nilashi, M.; Ghobakhloo, M. Determinants of environmental, financial, and social sustainable performance of manufacturing SMEs in Malaysia. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 35, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilu, R.; Darus, F.; Yusoff, H.; Mohamed, I.S. Preliminary insights on green criminology in Malaysia. J. Financ. Crime 2022, 29, 1078–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Segerson, K.; Wang, C. Is environmental regulation the answer to pollution problems in urbanizing economies? J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2023, 117, 102754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohd Hasnu, N.N.; Muhammad, I. Environmental issues in Malaysia: Suggestion to impose carbon tax/Norfakhirah Nazihah Mohd Hasnu and Izlawanie Muhammad. Asian-Pac. Manag. Account. J. 2022, 17, 65–95. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, M.S.M.; Hasan, N.N.N. Analysing Islamic Elements in Environmental News Reporting in Malaysia. Media Watch 2019, 10, 54–67. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad Saleh, M.S.; Md Kassim, N.; Alhaji Tukur, N. The influence of sustainable branding and opinion leaders on international students’ intention to study: A case of Universiti Sains Malaysia. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 23, 565–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahirah, N.; Othman, A.; Mohd Nor, N. Maqasid Shariah Applications as a Parameter for Muslim Tourism Package in Malaysia. In Proceedings of the UUM International Islamic Business Management Conference 2020 (IBMC 2020), Online, 24–30 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gunardi, S.; Mochammad Sahid, M.; Zahalan, N. The Concept of Dynamic Harmonies on Religious Life in Malaysia throught the Syariah Maqasid Approach. J. Islam. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2020, 23, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Fisol, W.N.; Fatimah, S. The Engineering of the Maqasid Shariah Theory through the Scientific Methodology of Al- Quran and Al-Sunnah in Islamic Finance. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2019, 2, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, G.P.; Locke, E.A. Self-regulation through goal setting. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 212–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenberg, S.; Steg, L. Normative, Gain and Hedonic Goal Frames Guiding Environmental Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn-Sze, J.C. Female leadership communication styles from the perspective of employees. J. Media Commun. Res. 2021, 13, 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, J.; Keum, H.; Shah, D.V. News Consumers, Opinion Leaders, and Citizen Consumers: Moderators of the Consumption–Participation Link. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 2014, 92, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, D.S.; Bakhshian, S.; Eike, R. Engaging consumers with sustainable fashion on Instagram. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2021, 25, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L. Social influence approaches to encourage resource conservation: A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaruddin, H.; Patittingi, F.; Assidiq, H.; Bachril, S.N.; Mukarramah, A.; Habaib, N. Legal Aspect of Plastic Waste Management in Indonesia and Malaysia: Addressing Marine Plastic Debris. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalli, N.B. The effectiveness of social media in assisting opinion leaders to disseminate political ideologies in developing countries: The case of Malaysia. J. Komun. Malays. J. Commun. 2016, 32, 551–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, M.S.A.; Yusof, M.A.M.; Ali, S.M. Wellbeing of the society: A Maqāşid Al-sharī‘ah approach. Afkar 2020, 2020, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Hoque, M.N.; Muda, R. Assessment of the Sharīʿah requirements in the Malaysian Islamic Financial Services Act 2013 from the managerialism and Maqāṣid al-Sharīʿah perspectives. J. Islam. Account. Bus. Res. 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahyudin, W.A.t.; Rosman, R. Performance of Islamic banks based on maqāṣid al-sharīʿah: A systematic review of current research. J. Islam. Account. Bus. Res. 2022, 13, 714–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H. Examining new measure of asnaf muslimpreneur success model: A Maqasid perspective. J. Islam. Account. Bus. Res. 2022, 13, 596–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Long, R.; Chen, H.; Yang, J. Does social interaction have an impact on residents’ sustainable lifestyle decisions? A multi-agent stimulation based on regret and game theory. Appl. Energy 2019, 251, 113366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratel, Y. Sustainable Lifestyles—An Experiment in Living Well: Northern European Examples of Sustainable Planning. Urbana Och Regionala Studier, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, 2012. Master Project.

- Lewis, A.; Chen, H. Framework for Shaping Sustainable Lifestyles: Determinants and Strategies; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Simon Gilby, C.M.; Koide, R.; Watabe, A.; Akenji, L.; Timmer, V. Sustainable Lifestyles Policy and Practice: Challenges and Way Forward; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies: Hayama, Japan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme One Earth. Sustainable Lifestyles: Options and Opportunities; UN Environment: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- El-Mesawi, M.E.T. Maqasid Al-Shart’ah: Meaning, Scope and Ramifications. Al-Shajarah 2020, 25, 263–295. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkawi, A.A.; Abdullah, A.; Dali, N.M.; Khazani, N.A.M. The philosophy of Maqasid Al-Shari’ah and its application in the built environment. J. Built Environ. Technol. Eng. 2017, 2, 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.; Feinberg, R.A. The LOHAS Lifestyle and Marketplace Behavior. In Handbook of Engaged Sustainability; Marques, J., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1069–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, J.; Woo, H. Investigating male consumers’ lifestyle of health and sustainability (LOHAS) and perception toward slow fashion. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 49, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). The Asia-Pacific Low-Carbon Lifestyles Challenge. Available online: https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/news/asia-pacific-low-carbon-lifestyles-challenge (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Afridi, M.A.K. Maqasid Al-Shari ah and preservation of basic rights under the theme@ Islam and its perspectives on global & local contemporary challenges. J. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2016, 4, 274–285. [Google Scholar]

- Haji Wahab, M.Z.; Mohamed Naim, A. The Reviews on Sustainable and Responsible Investment (SRIs) Practices According to Maqasid Shariah and Maslahah Perspectives. ETIKONOMI 2021, 20, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaakub, S.; Abdullah, N.A.H.N. Towards Maqasid Shariah in Sustaining The Environment Through Impactful Strategies. Int. J. 2020, 5, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.S.; Hasan, H. Measuring Deprivation from Maqāṣid Al-SharīʿAh Dimensionsin OIC Countries: Ranking and Policy Focus. J. King Abdulaziz Univ. Islam. Econ. 2018, 31, 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, M.J.; Smolarski, J.M. Religion and CSR: An Islamic “Political” Model of Corporate Governance. Bus. Soc. 2020, 59, 823–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Kruglanski, A.W. Reasoned action in the service of goal pursuit. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 126, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, K.; Phipps, D.J.; Schmidt, P.; Bamberg, S.; Ajzen, I. First test of the theory of reasoned goal pursuit: Predicting physical activity. Psychol. Health 2022, 62, 102222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindenberg, S. Social rationality, semi-modularity and goal-framing: What is it all about? Anal. Krit. 2008, 30, 669–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, D.; Pelletier, L.G. The roles of motivation and goals on sustainable behaviour in a resource dilemma: A self-determination theory perspective. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trask, S.; Shipman, M.L.; Green, J.T.; Bouton, M.E. Some factors that restore goal-direction to a habitual behavior. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2020, 169, 107161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mili, M. A Structural Model for Human Development, Does Maqāṣid al-Sharīʿah Matter! Islam. Econ. Stud. 2014, 22, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizam, I.; Larbani, M. A Structural Equation Model of Maqasid Al-Shari’Ah as a Socioeconomic Policy Tool. Policy Discuss. Maqasid Al-Shari’ah Socioecon. Dev. Ed. 2016, 1, 151–184. [Google Scholar]

- Bamakan, S.M.H.; Nurgaliev, I.; Qu, Q. Opinion leader detection: A methodological review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 115, 200–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parau, P.; Lemnaru, C.; Dinsoreanu, M.; Potolea, R. Chapter 10—Opinion Leader Detection. In Sentiment Analysis in Social Networks; Pozzi, F.A., Fersini, E., Messina, E., Liu, B., Eds.; Morgan Kaufmann: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Littlejohn, S.W.; Foss, K.A. Encyclopedia of Communication Theory; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Breesawitz, S.R. Conflict and Criticism: The Role of Leaders in Influencing Environmental Behavior. In Encyclopedia of the World’s Biomes; Goldstein, M.I., DellaSala, D.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 368–373. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet, M.C.; Kotcher, J.E. A two-step flow of influence?: Opinion-leader campaigns on climate change. Sci. Commun. 2009, 30, 328–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, L.R.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Eastman, J.K. Opinion leaders and opinion seekers: Two new measurement scales. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1996, 24, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, J.K.; Iyer, R.; Liao-Troth, S.; Williams, D.F.; Griffin, M. The Role of Involvement on Millennials’ Mobile Technology Behaviors: The Moderating Impact of Status Consumption, Innovation, and Opinion Leadership. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2014, 22, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Zamora, J.; García-Madariaga, J. Does opinion leadership influence service evaluation and loyalty intentions? Evidence from an arts services provider. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 39, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Liang, E.; Wu, Y. Accumulation mechanism of opinion leaders’ social interaction ties in virtual communities: Empirical evidence from China. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 82, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Jang, S.; Adler, H. What drives café customers to spread eWOM? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Haq, M.A.; Abd Wahab, N. The Maqasid Al Shariah and the Sustainability Paradigm: Literature Review and Proposed Mutual Framework for Asnaf Development. J. Account. Financ. Emerg. Econ. 2019, 5, 179–196. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, H.; Ali, S.S.; Muhammad, M. Towards a Maqāsid al-Sharī ‘ah Based Development Index. J. Islam. Bus. Manag. 2018, 8, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, L.S.; Sankar, P.L.; Boyer, J.; Jean McEwen, J.D.; Kaufman, D. Normative and conceptual ELSI research: What it is, and why it’s important. Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, E.M.; Ramos, M.O.; Alexander, A.; Jabbour, C.J.C. A systematic review of empirical and normative decision analysis of sustainability-related supplier risk management. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dali, N.M.; Abdullah, A.; Islam, R. Prioritization of the indicators and sub-indicators of Maqasid al-Shariah in measuring liveability of cities. Int. J. Anal. Hierarchy Process 2018, 10, 348–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, M.; Awang, Z.; Ali, N.A.M. Validating the maqasid shariah prison quality of Life (MSPQoL) among drug-abuse inmates using confirmatory factor analysis. Int. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. Res. 2017, 15, 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Yusof, S.A.; Budiman, M.A.; Amin, R.M.; Abideen, A. Holistic development and wellbeing based on MAQASID AL-SHARI’AH: The case of south kalimantan, Indonesia. J. Econ. Coop. Dev. 2019, 40, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Elviandari, E.; Farkhani, F.; Dimyati, K.; Absori, A. The formulation of welfare state: The perspective of Maqāid al-Sharī’ah. Indones. J. Islam Muslim Soc. 2018, 8, 117–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, W.; Lee, S. Stimulating visitors’ goal-directed behavior for environmentally responsible museums: Testing the role of moderator variables. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalman, M.D.; Chatterjee, S.; Min, J. Negative word of mouth for a failed innovation from higher/lower equity brands: Moderating roles of opinion leadership and consumer testimonials. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 115, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebauer, S. Why early adopters engage in interpersonal diffusion of technological innovations: An empirical study on electric bicycles and electric scooters. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2015, 78, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, N.; Swim, J.K.; Glenna, L. Spread the Green Word: A Social Community Perspective into Environmentally Sustainable Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 561–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoric, M.M.; Zhang, N. Opinion Leadership, Media Use, and Environmental Engagement in China. Int. J. Commun. 2019, 13, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan, V.; Tillmanns, S.; Krafft, M.; Asselmann, D. Understanding the quality–quantity conundrum of customer referral programs: Effects of contribution margin, extraversion, and opinion leadership. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2018, 46, 1108–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Statistics, Malaysia. The Key Findings Income—Poverty—Inequality—Expenditure—Basic Amenities. 2019. Available online: https://www.dosm.gov.my/portal-main/release-content/household-income-&-basic-amenities-survey-report-2019 (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Ahamad, N.R.; Ariffin, M. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice towards sustainable consumption among university students in Selangor, Malaysia. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 16, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayah, T.; Cheah, J.; Chuah, F.; Ting, H.; Memon, M.A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using smartPLS 3.0; An Updated Guide and Practical Guide to Statistical Analysis; Pearson: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarski, D. The measurement of gender expression in survey research. Soc. Sci. Res. 2023, 110, 102845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, C.; Wilson, J.; Griffin, H.; Tingle, A.; Cooper, T.; Semple, M.G.; Enoch, D.; Lee, A.; Loveday, H. The role of pandemic planning in the management of COVID-19 in England from an infection prevention and control perspective: Results of a national survey. Public Health 2023, 217, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, B.; Iyer, E.S. Motivating Sustainable Behaviors: The Role of Religiosity in a Cross-Cultural Context. J. Consum. Aff. 2021, 55, 792–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njølstad, B.W.; Mengshoel, A.M.; Sveen, U. ‘It’s like being a slave to your own body in a way’: A qualitative study of adolescents with chronic fatigue syndrome. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 26, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarstedt, M.; Cheah, J.-H. Partial least squares structural equation modeling using SmartPLS: A software review. J. Mark. Anal. 2019, 7, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Memon, M.A.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ramayah, T.; Ting, H.; Chuah, F.; Cham, T.H. Moderation analysis: Issues and guidelines. J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Model. 2019, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. Handb. Mark. Res. 2017, 26, 587–632. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, D.A. Moderator Variables: Introduction. Available online: http://davidakenny.net/cm/moderation.htm (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Fajzi, G.; Erdei, S. Sustainable positive mental health. Enhancing positive mental health through sustainable thinking and behavior. Mentálhigiéné Pszichoszomatika 2015, 16, 55–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosua, A.; Chang, S.; Deguchi, H. Opinion leaders’ influence and innovations adoption between risk-averse and risk-taking farmers. Int. J. Agric. Resour. Gov. Ecol. 2019, 15, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mulla, S.; Ari, I.; Koç, M. Social media for sustainability education: Gaining knowledge and skills into actions for sustainable living. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2022, 29, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbert, R.L.; Park, E. Conceptualizing, Organizing, and Positing Moderation in Communication Research. Commun. Theory 2019, 30, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.R.; Silva, E.A. Mapping the Landscape of Behavioral Theories: Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Lit. 2020, 35, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).