Abstract

This study investigated the influence of organizational democracy on organizational citizenship behaviors in digital transformation, by considering the mediating effects of job satisfaction and organizational commitment for smart services. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to investigate the factors, which was followed by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and path analysis to test the hypotheses. The sample consisted of 144 full-time employees of the largest bank in North Cyprus. The findings suggest that organizational democracy had a significant positive direct effect on the job satisfaction and organizational commitment, whereas the direct effect on the organizational citizenship behaviors was not significant. The mediating effect of organizational commitment was found to be significantly positive. Job satisfaction was found not to be a significant mediator. The indirect effect of organizational democracy on the organizational citizenship behaviors was significant.

1. Introduction

In the last few decades, organizational democracy has been becoming more relevant in order to improve employee performance and behavior. The changing organizational context and business environment has urged organizations to implement new managerial styles and adopt new philosophies that create a supportive, innovative, democratic, and ethical organizational climate [1,2]. Among these philosophies, organizational democracy serves as a model that is an ethical and efficient alternative to manage today’s modern organizations [3,4,5]. A democratic organization can be described as one with the active participation of all stakeholders toward the common goal of creating value for the organization and its stakeholders [6]. The active engagement of stakeholders is necessary in order to observe organizational democracy [7]. Geckil and Tikici [3] suggested organizational democracy as a tool to achieve better organizational performance. Organizational democracy creates a democratic climate within an organization, where employees and managers can communicate efficiently [8,9]. Thereby, employees can contribute to the decision-making process within the organization. Organizational democracy is defined as broad-based with institutionalized employee-influencing processes that are not occasional or ad hoc in nature [10]. In this study, the concept of organizational democracy requires employee participation, organizational justice, accountability, and transparency within the workplace [3].

Several organizational outcomes can be promoted by implementing organizational democracy within the workplace such as trust [11], organizational citizenship behaviors (OCB) [12,13], job satisfaction and commitment [14,15], and turnover intentions [12]. However, the influence of organizational democracy on different employee behaviors has only been studied by a limited number of empirical studies [15].

Based on the increase in novel digital innovations [16], digital transformation has remained a topical issue in education [17], health [18], banking [16,18], and other academic fields. Organizations, in basically all areas, are directing numerous drives to investigate and take advantage of digital transformation benefits [16,19]. Recognizing the competitive nature of the banking sector, Alhosani and Tariq [20] noted that the vast majority of banks have modified their policies and roles to provide smart services via web-based applications, which are products of digital transformation, making service quality turns into a fundamental system for such organizations that will affect their capacity to retain their level of competitiveness and profitability potentials.

A lot of contemporary professional and academic interest in investigating digital transformation and organization frameworks has zeroed in on the organizations’ external forces or the technology, neglecting internal forces [21], specifically the employees’ psychologically driven factors [22] such as OCB, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment [23], which can have effects on several factors such as work meaningfulness, retention, and turnover.

The existing studies on the influence of organizational democracy on OCB, job satisfaction, and commitment reported inconclusive and complex findings. Therefore, a consensus could not be achieved within the existing literature [12]. Moreover, the majority of the studies that focused on employee engagement/participation and organizational behaviors did not consider democratic organizations in their samples [15].

The significance of this study is embedded in the focus of the study to direct empirical exploration toward recognizing internal forces in digital transformation and organizational frameworks, specifically the employees’ psychologically driven factors, by exploring the effects of organizational democracy on OCB in digital transformation via the mediating role of job satisfaction and organizational commitment for smart services, which are products of digital transformation. This study will definitely add to the existing body of literature on digital transformation, OCB, organizational democracy, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and smart services.

Purpose of the Study

This study has several objectives. First, in order to fill the research gap, the influence of organizational democracy on employee behaviors such as OCB, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and social loafing is examined. Secondly, examining the effect of organizational democracy on OCB through the mediating effects of job satisfaction, organizational commitment and social loafing is expected to support the relevant literature. Third, this study was intended to provide more insights into the concept of organizational democracy within the context of developing countries and the banking sector. The banking sector of the TRNC is a highly competitive industry that has significant contributions to the overall economy of the country. However, there is a limited number of studies that focused on banking sector employees. Lastly, it was aimed at providing guidelines and insights to managers in order to adapt their organizations to the changing context of the business environment.

2. Need for the Study

2.1. Role of Digital Transformation and Sustainable Smart Services

Matt, Hess, and Benlian [24] and Sahu, Deng, and Mollah [25] portrayed digital transformation as the change in an organization’s functions, structure, business models, and processes as a result of technology adoption. It is dependent on the indirect and direct impacts of applying digital technologies and methods to organizational and economic circumstances from one viewpoint and novel services and products from the other [26]. Bousdekis and Kardaras [27] referred to the concept of digital transformation from the perspective of the public sector as an innovative means of working with stakeholders, developing novel systems of service delivery, and building new systems of relationships.

Despite the fact that there is little debate with respect to the definition of smart services, different scholars accentuate various perspectives and attributes of smart services [25], although some factors, such as the providers, customers, and digital technologies, are central to the available definitions [28]. Smart services refer to services aided by digital products, which allude to products that show both digital components such as software, data storage, etc., and physical components such as electronic and mechanical parts [29,30].

Digital transformation plays a great role in establishing smart services in every sector. In this respect, paying attention to digital technologies within transformation becomes the essential focus of organizational structures [17,18]. Therefore, looking into the following terms, from the perspective of sustainable smart services in digital transformation, is highly needed for service quality in the future.

Digital transformation is a firm’s way of using digital technologies to develop a new, more affordable digital business model that helps create more value for the. This type of transformation affects business processes, operational routines, and organizational capabilities [31,32,33].

Digital transformation, caused by the changes created by the application of digital technology in all areas of human society, adopts digital technologies and transforms elements such as business strategy, digital strategy, operation, product, marketing approach, and target. This is the renewal of and change within the business world. It is a service management system that provides a comprehensive solution, which accelerates the sales and growth of companies. The transformation phase means that digital uses enable new kinds of innovation and creativity in a given field, rather than simply amplifying and supplementing traditional methods [34,35,36,37].

2.2. Organizational Democracy

The multidimensional construct of organizational democracy has its basis in politics, organizational psychology, and in the management literature. Employee participation, workplace democracy, and participative management style are different conceptualizations of organizational democracy within the literature [4,13]. Ahmed, Adeel, Ali, and Rehman [12] defined organizational democracy as “a responsibility toward the governed ones: equal rights of participation; free movement of information; and representation of the governed subjects”. Similarly, [6] defined organizational democracy as the share of power between groups of people within the organization and the shared contribution of decision-making practices among employees. Thus, organizational democracy can be a way of mitigating the dysfunctional behavior of employees and improving their performance [13]. Geckil and Tikici [3] defined organizational democracy as the implementation of political and governmental democracy within an organization as a tool. Tutar, Tuzcuoglu, and Altınöz [38] typified organizational democracy as the participation of employees toward the common will of the organization. The active participation of employees in the management and governance of the organization means organizational duties and responsibilities are distributed to the employees regarding the process of decision making [39].

Organizational democracy was separated and conceptualized as six dimensions by [3], which aimed to develop an organizational democracy scale. As a result of reviewing the previous literature, the authors proposed seven dimensions: participation, criticism, transparency, justice, equality, accountability, and power [3]. Participation is the active participation of employees at all levels of the mechanisms within the organization and contributes to decision making [40]. Geckil and Tikici [3] proposed participation, which refers to the active contribution of employees to all stages of decision making within the organization. This can make the employees feel important to the organization, and, thus, they will develop positive perceptions of the organization. The criticism dimension of organizational democracy involves the evaluation and criticism of the policy and procedures within and about an organization by the employees [3]. Organizational transparency is the timely disclosure and communication of accurate information by an organization [41]. Moreover, it emphasizes that the information must be openly shared with all stakeholders, so it can be classified as a transparent disclosure of information [41]. According to [3], organizational justice indicates the employees’ perceptions of these processes on the basis of equality, fairness, and justice. Employees will likely positively perceive the fairness behind the allocation of rewards and punishment. The equality dimension of organizational democracy refers to providing equal opportunities to every employee within an organization. The rights that are provided by the policies of the organization should be equally distributed to the employees [3]. The accountability dimension of organizational democracy refers to the degree of accountability for certain actions carried out by employees and the organization’s managers. According to [42], organizations and employees must be kept accountable for their actions and should acknowledge the consequences. Power sharing is defined by [43] as the influence of one employee on another, which affects their behavior. The power dimension includes the share of power amongst employees, the process of decision making, and the process of deciding employees’ levels of power [3].

2.3. Organizational Democracy and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors Nexus

OCB is defined as discretionary or extra-role behaviors of employees at the workplace that are voluntary in nature [44]. According to [45], OCB can be defined as employees’ behaviors that are voluntary and not expected by their job requirements or rewarded by the organization. OCB is used synonymously with extra-role behaviors within the literature. Organ [44] and Konovsky and Organ [46] defined OCB as conceptually encompassing five dimensions: conscientiousness, courtesy, civic virtue, altruism, and sportsmanship. Recently, OCB has been divided into two aspects: OCB for the organization (OCB-O) and OCB for individuals (OCB-I) [47]. OCB-I covers altruism and kindness, while OCB-O covers civic virtue, conscientiousness, and sportsmanship [48,49].

In the current age, the competitive business environment requires organizations to go beyond their duties and to have employees who want to add value to organizations. Sesen and Basim [49] emphasized that employees who are willing to show extra-role behaviors demonstrate a higher level of cooperation and enhance productivity within the workplace. In accordance with the social cognitive theory proposed, a democratic climate within the workplace can affect employees’ behaviors [50,51]. Organizational democracy contributes to various pro-social organizational behaviors, which include OCB [46]. The democratic climate within an organization influences the employees to participate in decision-making processes throughout the organization. Therefore, they can recognize the importance of employee participation and extra-role behaviors for the organization, as they benefit the whole organization and its stakeholders. This can improve cooperation within the organization and also improve pro-social behaviors such as OCB [52,53]. The social cognitive theory suggests that a democratic organization and democratic organizational climate affect the pro-social behaviors of employees such as OCB [51]. In this study, two dimensions of OCB were adopted, as categorized by [47], with subdivisions: altruism and courtesy, which make up OCB toward individuals (OCB-I); conscientiousness, civic virtue, and sportsmanship, which makeup OCB toward organizations (OCB-O).

Therefore, it is proposed that organizational democracy enhances employees’ OCB.

H1.

Organizational democracy has a positive influence on organizational citizenship behaviors.

2.4. Mediating Roles of Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment

The implementation of organizational democracy is expected to have significant benefits for the organization and its stakeholders. Harrison and Freeman [6] concluded that democracy within the workplace led to increased commitment, satisfaction, and productivity of employees with improved participation within the workplace. A democratic culture will not only help satisfaction and commitment but also create freedom of speech and an opportunity for whistleblowing within the company [54]. It has been proven by previous research that the democratic practices of an organization can influence the organizational climate and culture, so employees tend to show positive employee behaviors [15,53]. According to [13], organizational citizenship behaviors can be improved as a result of these positive employee behaviors.

A democratic organization provides more rights and power to employees, which improves their psychological needs such as self-fulfillment and self-esteem [51]. This is expected to enhance workplace efficiency and the effectiveness of employees by reducing conflicts within the organization [55]. The existing literature provides evidence for the influence of organizational democracy on various organizational outcomes such as OCB [13], job satisfaction and organizational commitment [14], employee participation and engagement [6], equality within the workplace [56], cooperation and collaboration within between employees [5], and employee well-being.

Social exchange theory has been used to define the effect of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on OCB [57]. It is possible for a satisfied and dedicated employee to increase and respond to out-of-role behaviors in the workplace [58]. Locke [59] explained that job satisfaction is expressed as a pleasurable or positive emotional state, as a result of the evaluation of an employee’s work and work experience. In addition, job satisfaction significantly contributes to the OCB of employees [45,48,60]. A meta-analysis of 55 studies conducted by [45] provided significant evidence for the influence of job satisfaction on OCB. Together with job satisfaction, organizational commitment is also a contributor to the OCB of employees [61,62]. Organizational commitment is defined as employees’ identification with, endogenizing of, and involvement in organizational goals and objectives. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment have been proven to be a contributor to OCB in various studies [63,64]. Perceived organizational democracy is expected to influence the organizational commitment and job satisfaction of employees [15,65]. According to [66], organizations enhance democracy within the workplace in order to enhance employees’ satisfaction and commitment. Therefore, it is proposed that organizational democracy enhances job satisfaction and organizational commitment, which improves OCB.

H2.

Job satisfaction mediates the relationship between organizational democracy and organizational citizenship behaviors.

H3.

Organizational commitment mediates the relationship between organizational democracy and organizational citizenship behaviors.

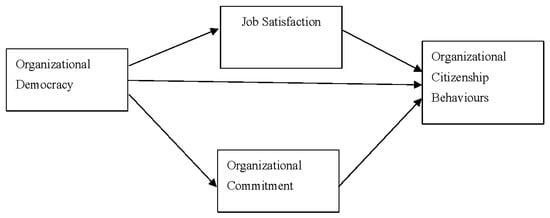

In light of the literature represented in this study, Figure 1 depicts the proposed relationship between variables.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3. Methodology

In this study, simple random sampling method was used, in which every employee of commercial banks has an equal opportunity of being selected from the entire population of commercial banks employees in North Cyprus, so the sample consists of full-time employees working at the commercial banks in North Cyprus. The authors distributed the questionnaires using a face-to-face approach with the employees. To indicate the aim, anonymity, and confidentiality of the research, a cover letter was included in the questionnaire. Social desirability bias was reduced by following [67] suggestions, and the same information was shared with the respondent orally. Completed questionnaires were collected within the period in order to reduce the common method bias [68]. A total of 200 questionnaires were distributed, and 144 were returned by the candidates, which represents a suitable sample size for this study [69]. In addition, t test was conducted to analyze the non-response bias, and the demographic distributions of the employees who answered the survey and those who did not respond were compared. The results showed that non-response bias was not observed in this research.

The data of this research were collected by using 5-point Likert scale questions, which range from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The total number of items included within the questionnaire was 113, including 8 items to measure demographic variables, 28 items to measure organizational democracy, 20 items to measure job satisfaction, 33 items to measure organizational commitment, and 24 items to measure OCB. The organizational democracy scale, developed by [3], includes items such as “management takes into consideration the criticisms by employees”. This scale includes six subdimensions: participation, criticism, transparency, justice, equality, and accountability. The job satisfaction scale, which is used in this study, was developed by Weiss, Dawis, and England [70], and includes items such as “I can use my abilities”. The OCB scale was developed by [71]. The scale consists of five subdimensions: courtesy and altruism toward the individuals who make up OCB (OCB-I) and the conscience, civic virtue, and sportsmanship that make up OCB for organizations (OCB-O). A sample item is “I help my co-workers with higher workloads’’. Lastly, the organizational commitment scale, developed by [72], includes items such as “I have a sense of belongingness towards my organization”.

The demographic information of the respondents is as follows. In total, 67% of the respondents were female, and 33% were male. The justification for dominance of females can be linked to women in finance in Turkey, which indicated that women have over 50% representation in the finance sector of Turkey; North Cyprus, as a protectorate of Turkey, is also a reflection of that report. Overall, 40% of the participants were between the ages of 18–29, the rate of participants aged 30–40 was 48%, and the rate of participants over 40 was 12%. When the educational status of the participants is examined, 10% of them were high school graduates, while the rate of participants with a bachelor’s degree was 67%, and the rate of participants with a graduate degree as 23%. While 55% of the participants in the research were married, 45% were not. In total, 20% of the respondents had 2 years or fewer years of experience, 33% of the respondents had experience levels between 2 and 5 years, 30% of the respondents had experience levels between 5 and 15 years, and 5% of the respondents had more than 15 years of experience.

4. Results

Analysis of a Moment Structures (AMOS) 21 and Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 21 were employed in order to analyze the data and test the proposed hypotheses. The initial stage of the analysis was the data-screening process, which checked the data for any missing or outlier observations. The second stage consisted of checking for the normality, linearity, homoscedasticity, and multicollinearity of the data. The third stage consisted of testing for the reliability and validity of the data. Lastly, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to investigate the factors, followed by path analysis and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test the hypotheses. The control variables did not have a significant contribution to the variables. Thus, they were excluded from the model [73].

Measurement Model

Results of the EFA showed that the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test was 0.803, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.01), which are satisfactory results. Table 1 shows the reliability, validity, and correlation matrix of the variables. Composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), and maximum shared variance (MSV) were used to measure the reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the constructs. Validity and reliability criteria were put forward by Hair, Black, Babin, and Anderson [74]. Accordingly, for convergent validity, the AVE should be higher than 0.50; it is stated that the CR should be greater than 0.70 to ensure reliability, and the MSV should be lower than the AVE for discriminant validity. The constructs met the criteria for reliability and validity. The common method variance was tested by using a common latent factor. The findings show that the common method variance was below 50%, which indicates that common method bias was not a problem.

Table 1.

Reliability and validity.

CFA was conducted using AMOS 21 software in order to test the construct loadings and model fit. The factor loadings, standard errors, and p-values are presented in Table 2. The goodness of fit indices considered were the comparative fit index (CFI), the goodness of fit index (GFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), the chi-squared mean/degree of freedom (CMIN/df), the root-mean-square error (RMSEA), and the standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR). According to the cut-off values suggested, GFI, CFI, and TLI must be above 0.90, RMSEA must be below 0.05, and SRMR must be below 0.09 [74]. The results of the CFA showed that the model has an acceptable model fit (CMIN/df = 1.42; CFI = 0.96; GFI = 0.90; TLI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.04; SRMR = 0.04).

Table 2.

Item loadings.

5. Hypothesis Testing

Table 3 presents the direct implications of the constructs, for testing the hypotheses and the mediating effects of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. First, a model excluding the mediators from the organizational democracy to the OCB was tested, which was found not to be significant (p > 0.05). Hypothesis 1, which proposed the direct effect of organizational democracy on OCB, is not accepted. According to [75], this indicates that a mediated model is superior to the direct effect model. This provided support for the mediating effects of job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Table 3.

Direct effects.

Organizational democracy had a significantly positive influence on job satisfaction (0.679, p < 0.01) and on organizational commitment (0.557, p < 0.01). In addition, organizational commitment was found to have a significantly positive influence on OCB (0.435, p < 0.01). The direct effect of job satisfaction and organizational democracy on OCB was found to be insignificant (p > 0.05).

Table 4 shows the indirect effect of organizational democracy on OCB through the mediating effects of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. In order to analyze the indirect effects, 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals (N = 5000) were conducted. The results showed that job satisfaction does not significantly mediate the relationship between organizational democracy and OCB (p > 0.05), whereas organizational commitment was found to be a significant and positive mediator between organizational democracy and OCB (0.245, p < 0.01).

Table 4.

Mediating effects.

Therefore, hypothesis 2, which proposed the mediating effect of job satisfaction between organizational democracy and OCB, is not accepted. Hypothesis 3, which proposed the mediating effect of organizational commitment between the organizational democracy and OCB, is accepted.

6. Discussion

Recent models of organizational systems have focused on the fundamentals of flexibility, endorsement, and enhanced communication within organizations [76]. Increased organizational democracy enhances organizational performance [77,78]. The main aim of this study was to investigate the influence of democratic practices within an organization on employee behaviors. First, it was proposed that job satisfaction mediates the relationship between organizational democracy and OCB. Second, it was proposed that organizational commitment mediates the relationship between organizational democracy and OCB. Further insights into the concept of organizational democracy were also provided. The findings confirmed the importance of enhancing organizational democracy within the workplace, as it has a direct and significant influence on job satisfaction and organizational commitment and an indirect influence on OCB. The findings also supported the social cognitive theory and social exchange theory.

The literature provides evidence that organizational democracy has an influence on the employee behaviors such as commitment, satisfaction, trust, turnover, and citizenship behaviors [6,12,54]. The findings of this study are in line with the studies that have concluded that organizational democracy has a positive effect on organizational commitment [4,79]. A study conducted by [4] found significant evidence that organizational democracy has a positive influence on commitment within a sample of 263 gas company employees. In addition, renference [80] claimed that organizational democracy should be implemented with a normative approach in order to observe organizational commitment. This will give employees more freedom and motivation to contribute and participate in organizational decision making and, thus, increase commitment [81]. As well as commitment, job satisfaction is also a significant construct that is affected by organizational democracy. According to [82], adopting democratic practices within the organization enhances satisfaction and commitment. Çakar and Yildiz [83] confirmed that justice, as one of the dimensions of democracy, increased the job satisfaction of employees. Weber, Unterrainer, and Höge [51] conducted a meta-analysis of 60 studies and concluded that the participation dimension of democracy contributes to the job satisfaction of employees.

Furthermore, organizationnal democracy influences OCB [13] and also perceived servant leadership can be achieved through organizational democracy and can reduce workplace bullying [16], Adeel, Ali, and Rehman [12] conducted a study in Pakistan and confirmed the influence of empowerment on various organizational behaviors including commitment, OCB, and turnover intentions. This study provided evidence that organizational democracy has an indirect effect on OCB through organizational commitment.

7. Conclusions

Organizational democracy as a dynamic concept is a key aspect of sustainable organizational performance. This study provided empirical evidence and contributed to the existing body of literature on organizational democracy, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and OCB. The importance of organizational democracy was supported, as it was found to be a significant and direct positive contributor to job satisfaction and organizational commitment, indirectly contributing to OCB. The mediating effect of organizational commitment was also supported. The results showed that in order to observe the effect of organizational democracy on OCB, organizational commitment should exist.

7.1. Theoretical Implications

This study provided significant evidence that organizational democracy has effects on OCB, that empowerment enhanced by organizational democracy can also increase OCB, and that organizational democracy has an indirect effect on OCB through organizational commitment.

7.2. Practical Implications

These findings can provide a road map for managers working in the banking sector, which is a highly labor-intensive industry. Managers should focus on creating a democratic climate within their organizations, in order to achieve various employee outcomes that, in turn, can contribute to the types of employee behaviors that are critical for organizational performance. Enhancing participation, criticism, transparency, justice, equality, and accountability within an organization can help companies to observe increased job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and OCB.

7.3. Limitations and Future Directions

However, this research had certain limitations, such as its focus on one sector, which can limit the generalizability of the findings. It is also essential to note that this study controlled the position held by bank employees by holding it as a constant. Further research should focus on different industries and countries, account for the position held by bank employees, and investigate different employee outcomes such as trust.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.H., T.S. and S.E.; methodology, S.E.; software, T.S.; validation, S.E. and C.S.G.H.; formal analysis, E.H., T.S. and S.E.; investigation, E.H., T.S. and S.E; resources, C.S.G.H.; data curation, T.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.H.; writing—review and editing, T.S.; visualization, S.E.; supervision, T.S.; project administration, S.E.; funding acquisition, E.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical Committee of Near East University in January 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Handy, C.B. The Second Curve: Thoughts on Reinventing Society; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, S.; Tripathi, D. Organizational climate and organizational politics: Understanding the role of employees using parallel mediation. In Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Geckil, T.; Tikici, M. A Study on Developing the Organizational Democracy Scale. Amme İdaresi Derg. 2015, 48, 41–78. Available online: http://abakus.inonu.edu.tr/xmlui/handle/11616/14567 (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Safari, A.; Salehzadeh, R.; Ghaziasgar, E. Exploring the antecedents and consequences of organizational democracy. TQM J. 2018, 30, 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdorfer, A.P.; Weber, W.G.; Unterrainer, C.; Seyr, S. The relationship between organizational democracy and socio-moral climate: Exploring effects of the ethical context in organizations. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2013, 34, 423–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.S.; Freeman, R.E. Is Organizational Democracy Worth the Effort? Acad. Manag. Exec. (1993–2005) 2004, 18, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Norval, A.J. Democratic Identification: A Wittgensteinian Approach. Political Theory 2006, 34, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frega, R. Firms as coalitions of democratic cultures: Towards an organizational theory of workplace democracy. Crit. Rev. Int. Soc. Political Philos. 2022, 25, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stohl, C.; Cheney, G. Participatory Processes/Paradoxical Practices: Communication and the Dilemmas of Organizational Democracy. Manag. Commun. Q. 2001, 14, 349–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegge, J.; Jeppesen, H.J.; Weber, W.G.; Pearce, C.L.; Silva, S.A.; Pundt, A.; Jonsson, T.; Wolf, S.; Wassenaar, C.L.; Unterrainer, C. Promoting work motivation in organizations: Should employee involvement in organizational leadership become a new tool in the organizational psychologist′s kit? J. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 9, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzhausen, D.R. The Effect of Workplace Democracy on Employee Communication Behaviour: Implications for Competitive Advantage. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2002, 12, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Adeel, A.; Ali, R.; Rehman, R.U. Organizational democracy and employee outcomes: The mediating role of organizational justice. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2019, 2, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geckil, D.T.; Tikici, M. Hospital employees′ organizational democracy perceptions and its effects on organizational citizenship behaviors. Asian Pac. J. Health Sci. 2016, 3, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterrainer, C.; Palgi, M.; Weber, W.G.; Iwanowa, A.; Oesterreich, R. Structurally anchored organizational democracy: Does it reach the employee? J. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 10, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, W.G.; Unterrainer, C.; Schmid, B.E. The influence of organizational democracy on employees′ socio-moral climate and prosocial behavioral orientations. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 1127–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snape, E.; Redman, T. HRM Practices, Organizational Citizenship Behaviour, and Performance: A Multi-Level Analysis. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 1219–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedoyin, O.B.; Soykan, E. COVID-19 pandemic and online learning: The challenges and opportunities. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omarini, A. The digital transformation in banking and the role of FinTechs in the new financial intermediation scenario. Int. J. Financ. Econ. Trade 2017, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, J.; Amorim, M.; Melão, N.; Matos, P. Digital transformation: A literature review and guidelines for future research. In World Conference on Information Systems and Technologies; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 411–421. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S.; Schiavone, F.; Pluzhnikova, A.; Invernizzi, A.C. Digital transformation in healthcare: Analyzing the current state-of-research. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhosani, F.A.; Tariq, M.U. Improving Service quality of smart banking using quality management methods in UAE. Int. J. Mech. Prod. Eng. Res. Dev. 2020, 10, 2249–8001. [Google Scholar]

- Kozanoglu, D.C.; Abedin, B. Understanding the role of employees in digital transformation: Conceptualization of digital literacy of employees as a multi-dimensional organizational affordance. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2020, 34, 1649–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romi, M.; Soetjipto, N.; Widaningsih, S.; Manik, E.; Riswanto, A. Enhancing organizational commitment by exploring job satisfaction, organizational citizenship behavior and emotional intelligence. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2021, 11, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, B. Bank failure in Nigeria: A consequence of capital inadequacy, lack of transparency and non-performing loans? Banks Bank Syst. 2011, 6, 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Matt, C.; Hess, T.; Benlian, A. Digital transformation strategies. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2015, 57, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, N.; Deng, H.; Mollah, A. Investigating the critical success factors of digital transformation for improving customer experience. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Resources Management (CONF-IRM), Ningbo, China, 3–5 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Anke, J. Design-integrated financial assessment of smart services. Electron. Mark. 2019, 29, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousdekis, A.; Kardaras, D. Digital transformation of local government: A case study from Greece. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 22nd Conference on Business Informatics (CBI), Antwerp, Belgium, 22–24 June 2020; Volume 2, pp. 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer, S.; Olivotti, D.; Lebek, B.; Breitner, M.H. Focusing the customer through smart services: A literature review. Electron. Mark. 2019, 29, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. Women in Finance in Turkey. 2017. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/tr/en/pages/financial-services/articles/turkiyede-finans-dunyasinda-kadin.html (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Ahmad, S.; Islam, T.; D’Cruz, P.; Noronha, E. Caring for those in your charge: The role of servant leadership and compassion in managing bullying in the workplace. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2022, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Su, F.; Zhang, W.; Mao, J.Y. Digital transformation by SME entrepreneurs: A capability perspective. Inf. Syst. J. 2018, 28, 1129–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Broekhuizen, T.; Bart, Y.; Bhattacharya, A.; Dong, J.Q.; Fabian, N.; Haenlein, M. Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarazzo, M.; Penco, L.; Profumo, G.; Quaglia, R. Digital transformation and customer value creation in Made in Italy SMEs: A dynamic capabilities perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 123, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, T.; Matt, C.; Benlian, A.; Wiesböck, F. Options for formulating a digital transformation strategy. MIS Q. Exec. 2016, 15, 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Hess, T. How chief digital officers promote the digital transformation of their companies. MIS Q. Exec. 2017, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tutar, H.; Tuzcuoglu, F.; Altınöz, M. Kurumsal demokrasinin algılanması üzerine karşılaştırmalı bir inceleme. In Proceedings of the International Davraz Congress, Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi, Isparta, Turkey, 24–27 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, P.F. Knowledge-Worker Productivity: The Biggest Challenge. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1999, 41, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, A.; Gollan, P.J.; Marchington, M.; Lewin, D. Conceptualizing Employee Participation in Organizations. In The Oxford Handbook of Participation in Organizations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnackenberg, A.K.; Tomlinson, E.C. Organizational Transparency: A New Perspective on Managing Trust in Organization-Stakeholder Relationships. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1784–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindkvist, L.; Llewellyn, S. Accountability, responsibility and organization. Scand. J. Manag. 2003, 19, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.P.; Judge, T. Organizational Behavior; Pearson: Boston, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books/D. C. Heath and Com.: Boston, MA, USA, 1988; p. xiii, 132. [Google Scholar]

- Organ, D.W.; Ryan, K. A meta-analytic review of attitudinal and dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship behavior. Pers. Psychol. 1995, 48, 775–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovsky, M.A.; Organ, D.W. Dispositional and contextual determinants of organizational citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 1996, 17, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, J.A.; Erez, A.; Johnson, D.E. The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: A critical review and meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cek, K.; Eyupoglu, S.Z. Does teachers′ perceived corporate social responsibility lead to organisational citizenship behaviour? The mediating roles of job satisfaction and organisational identification. S. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 50, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesen, H.; Basim, N.H. Impact of satisfaction and commitment on teachers′ organizational citizenship. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, W.G.; Unterrainer, C.; Höge, T. Psychological Research on Organisational Democracy: A Meta-Analysis of Individual, Organisational, and Societal Outcomes. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 69, 1009–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, D.; Reeves, E.; Turner, T. The impact of privatization and employee share ownership on employee commitment and citizen behaviour. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2010, 31, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, W.G.; Unterrainer, C.; Hoege, T. Sociomoral Atmosphere and Prosocial and Democratic Value Orientations in Enterprises with Different Levels of Structurally Anchored Participation. Ger. J. Res. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 22, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, N. Organizational Democracy and Organization Structure Link: Role of Strategic Leadership & Environmental Uncertainty. Soc. Sci. Res. Netw. 2006, 5, 1858264. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1858264 (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Battilana, J.; Fuerstein, M.; Lee, M. New prospoects for organizational democracy? How to joint pursuit of social and financial goals challenges traditional organizational designs. In Capitalism beyond Mutuality? Perspectives Integrating Philosophy and Social Science; Rangan, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Oseen, C. ‘It′s not only what we say but what we do’: Pay inequalities and gendered workplace democracy in Argentinian worker coops. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2016, 37, 219–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, S.; Gürbüz, S.; Sert, M. A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior: Test of potential moderator variables. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2015, 27, 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.; Keren, D. Individual Values and Social Exchange Variables: Examining Their Relationship to and Mutual Effect on In-Role Performance and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Group Organ. Manag. 2008, 33, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Dunnette, M.D., Ed.; Rand McNally College Pub. Co.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Foote, D.A.; Tang, T.L.-P. Job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB): Does team commitment make a difference in self-directed teams? Manag. Decis. 2008, 46, 933–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schappe, S.P. The Influence of Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, and Fairness Perceptions on Organizational Citizenship Behavior. J. Psychol. 1998, 132, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganster, D.C.; Schaubroeck, J. Work Stress and Employee Health. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 235–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currivan, D.B. The Causal Order of Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment in Models of Employee Turnover. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1999, 9, 495–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Scotter, J.; Motowidlo, S.J.; Cross, T.C. Effects of task performance and contextual performance on systemic rewards. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jong, G.; Van Witteloostuijn, A. Successful corporate democracy: Sustainable cooperation of capital and labor in the Dutch Breman Group. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2004, 18, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, D.; Clarke, M. Organizational politics: The cornerstone for organizational democracy. Organ. Dyn. 2002, 31, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Monroe, G.S. Exploring Social Desirability Bias. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, D.J.; Dawis, R.V.; England, G.W. Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. Minn. Stud. Vocat. Rehabil. 1967, 22, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Moorman, R.H.; Fetter, R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers′ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 1990, 1, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersitzke, M. Supervisor Psychological Contract Management; Gabler GWV Fachverlage: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson new internat. Ed.; Pearson: Essex, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Raykov, T.; Marcoulides, G.A. On desirability of parsimony in structural equation model selection. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, N. Telling Tales: Press, Politics, Power, and the Public Interest. Telev. New Media 2012, 13, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.S.; Wäger, M. Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: An ongoing process of strategic renewal. Long Range Plan. 2019, 52, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, M.; Kruschwitz, N.; Bonnet, D.; Welch, M. Embracing digital technology: A new strategic imperative. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2014, 55, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Medina, F.; López Bohle, S.; Jiang, L.; Chambel, M.J.; Ugarte, S.M. Qualitative job insecurity and voice behavior: Evaluation of the mediating effect of affective organizational commitment. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2022, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. An Exploration of Determinants of Organizational Commitment: Emphasis on the Relationship between Organizational Democracy and Commitment. Master’s Thesis, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, M.F.Y.; Wu, W. Participatory management and employee work outcomes: The moderating role of supervisor–subordinate guanxi. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2011, 49, 344–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirvis, P. Employee Engagement and CSR: Transactional, Relational, and Developmental Approaches. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2012, 54, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakar, N.D.; Yildiz, S. ÖRGÜTSEL ADALETİN İŞ TATMİNİ ÜZERİNDEKİ ETKİSİ: “ALGILANAN ÖRGÜTSEL DESTEK” BİR ARA DEĞİŞKEN Mİ? Elektron. Sos. Bilim. Derg. 2009, 8, 68–90. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).