Reducing the Negative Effects of Abusive Supervision: A Step towards Organizational Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

2.1. Abusive Supervision, Work Alienation and Psychological Well-Being

2.2. The Moderating Role of Perceived Job Mobility and Regulatory Focus

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Abusive Supervision

3.2.2. Work Alienation

3.2.3. Psychological Well-Being

3.2.4. Perceived Job Mobility

3.2.5. Regulatory Focus

3.2.6. Control Variables

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Construct Validity and Common Method Bias

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

6. Managerial Implications

7. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tepper, B.J.; Simon, L.; Park, H.M. Abusive supervision. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 123–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.; Tian, A.W.; Lee, A.; Hughes, D.J. Abusive supervision: A systematic review and fundamental rethink. Leadersh. Q. 2021, 32, 101540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B.J. Abusive supervision in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and research agenda. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 261–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, Y. The relationship between psychological contract breach and employees’ counterproductive work behaviors: The mediating effect of organizational cynicism and work alienation. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Liu, J. A study on the influence of career growth on work engagement among new generation employees. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 6, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Freedy, J. Conservation of resources: A general stress theory applied to burnout. In Professional Burnout; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Tepper, B.J. Consequences of abusive supervision. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Si, S. Tit for tat? Abusive supervision and counterproductive work behaviors: The moderating effects of locus of control and perceived mobility. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2013, 30, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.P.; Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Regulatory focus theory. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; van Lange, P.A.M., Kruglanski, A.W., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2012; pp. 483–504. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman, P.L. Life stress and psychological well-being: A replication of langner’s analysis in the midtown manhattan study. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1971, 12, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; May, D.R.; Schwoerer, C.E.; Deeg, M. “Called” to speak out: Employee career calling and voice behavior. J. Career Dev. 2022, 08948453211064943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, M.I.; Weng, Q.; Umrani, W.A.; Moin, M.F. Abusive supervision and career adaptability: The role of self-efficacy and coworker support. Hum. Perform. 2021, 34, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Gordon, S.; Tang, C.H. Momentary well-being matters: Daily fluctuations in hotel employees’ turnover intention. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schriesheim, C.A.; Castro, S.L.; Cogliser, C.C. Leader-member exchange (LMX) research: A comprehensive review of theory, measurement, and data-analytic practices. Leadersh. Q. 1999, 10, 63–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottaz, C.J. Some determinants of work alienation. Sociol. Q. 1981, 22, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Chen, Y.; Sun, P.; Li, C. Authoritarian leadership and employees’ unsafe behaviors: The mediating roles of organizational cynicism and work alienation. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 38, 1668–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttar, A.K.; Keir, M.Y.A.; Mahdi, O.R.; Nassar, I.A. Antecedents and consequences of work alienation–A critical. J. Stat. Appl. Probab. 2019, 8, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaburu, D.S.; Diaz, I.; De Vos, A. Employee alienation: Relationships with careerism and career satisfaction. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013, 28, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, T.G.; Finney, R.Z.; Maes, J.D. Abusive supervision and work alienation: An exploratory study. J. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 18, 78–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ronen, S.; Donia, M.M. From abusive supervision to work outcomes: The role of autonomous and controlled motivation. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirves, K.; Kinnunen, U.; De Cuyper, N. Contract type, perceived mobility and optimism as antecedents of perceived employability. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2014, 35, 435–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinley, S.P.; Martinez, L. The moderating role of career progression on job mobility: A study of work–life conflict. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 1106–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, C.; Law, K.S.; Chen, Z.X. A structural equation model of the effects of negative affectivity, leader-member exchange, and perceived job mobility on in-role and extra-role performance: A Chinese case. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1999, 77, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilhelm, F.; Hirschi, A. Career self-management as a key factor for career wellbeing. In Theory, Research and Dynamics of Career Wellbeing; Potgieter, I.L., Ferreira, N., Coetzee, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 117–137. [Google Scholar]

- Park, I.J.; Jung, H. Relationships among future time perspective, career and organizational commitment, occupational self-efficacy, and turnover intention. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2015, 43, 1547–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Ahmed, I. Mechanism between perceived organizational support and transfer of training: Explanatory role of self-efficacy and job satisfaction. Manag. Res. Rev. 2018, 41, 296–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawley, D.; Houghton, J.D.; Bucklew, N.S. Perceived organizational support and turnover intention: The mediating effects of personal sacrifice and job fit. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 150, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, K.; Peterson, S.J.; Zhang, Z.; LePine, J.A. Realizing challenges and guarding against threats: Interactive effects of regulatory focus and stress on performance. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 3011–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmann, J.; Lanaj, K.; Bono, J.; Campana, K. Daily shifts in regulatory focus: The influence of work events and implications for employee well-being. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 1293–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wang, L.; Lin, H. The role of cognitive processes and individual differences in the relationship between abusive supervision and employee career satisfaction. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 99, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanar, A.M.; Bouckenooghe, D. Job seekers’ self-directed learning activities explained through the lens of regulatory focus. J. Career Dev. 2021, 49, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.I.; Nisar, H.G.; Bashir, T.; Ahmed, B. Impact of aversive leadership on job outcomes: Moderation and mediation model. NICE Res. J. 2018, 11, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.; Lee, J.S. Assessing factor structure and convergent validity of the work regulatory focus scale. Psychol. Rep. 2014, 115, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.F.; Richter, A.W. Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: Development and application of a slope difference test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Xi, Y.; He, Z. Is green spread? the spillover effect of community green interaction on related green purchase behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.C.; Hsieh, H.H.; Wang, Y.D. Abusive supervision and employee engagement and satisfaction: The mediating role of employee silence. Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 1845–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, J.D.; Huang, L.; He, W. You abuse and I criticize: An ego depletion and leader–member exchange examination of abusive supervision and destructive voice. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 164, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammarra, A.; Profili, S.; Innocenti, L. Do external careers pay-off for both managers and professionals? the effect of inter-organizational mobility on objective career success. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 2490–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, P.P.; Carson, K.D. Demystifying demotion: A look at the psychological and economic consequences on the demote. Bus. Horiz. 2007, 50, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkmenoglu, M.A.; Cicek, B.; Erdur, D.A. Addressing leader-member exchange and self-regulation as remedies for work alienation: Insights from private and public sectors in Turkey. J. East Eur. Manag. Stud. 2022, 27, 311–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljegren, M.; Ekberg, K. Job mobility as predictor of health and burnout. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 1.94 | 0.79 | ||||||||||

| 2. Education | 0.77 | 0.42 | −0.34 ** | |||||||||

| 3. Tenure | 2.69 | 0.99 | 0.58 ** | −0.33 ** | ||||||||

| 4. Industry | 0.59 | 0.49 | −0.01 | −0.23 ** | −0.02 | |||||||

| 5. Abusive supervision | 1.29 | 0.53 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.07 | ||||||

| 6. Work alienation | 2.60 | 0.56 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.07 | 0.16 ** | 0.31 ** | |||||

| 7. PWB | 3.70 | 0.84 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.07 | −0.15 ** | −0.17 ** | ||||

| 8. Interorg.JM | 2.87 | 0.93 | −0.11 * | 0.15 ** | −0.09 | −0.02 | 0.10 * | −0.08 | −0.02 | |||

| 9. Intraorg.JM | 2.86 | 0.90 | −0.07 | 0.11 * | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.08 | −0.20 ** | 0.03 | 0.65 ** | ||

| 10. Promotion focus | 3.25 | 0.59 | −0.11 * | 0.08 | −0.14 ** | −0.01 | −0.07 | −0.17 ** | −0.08 | 0.23 ** | 0.27 ** | |

| 11. Prevention focus | 3.73 | 0.63 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.08 | −0.24 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.02 | 0.09 * | 0.16 ** | 0.42 ** |

| Variables | Dependent Variable: Work Alienation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderating Variable: Intraorg.JM | Moderating Variable: Interorg.JM | |||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Age | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 |

| Education | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| Tenure | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| Industry | 0.17 *** | 0.13 ** | 0.13** | 0.13 ** | 0.20 *** | 0.13 ** | 0.12 ** | 0.12 ** |

| Abusive supervision (AS) | 0.24 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.29 *** | ||

| Intraorg.JM | −0.14 *** | −0.14 *** | −0.15 *** | |||||

| Interorg.JM | −0.07 | −0.08 | −0.09 * | |||||

| Prevention focus (Pre-focus) | −0.18*** | −0.18*** | −0.19 *** | −0.19 *** | −0.18 *** | −0.17 *** | ||

| Promotion focus (Pro-focus) | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.06 | ||

| AS × Intraorg.JM | −0.04 | −0.06 | ||||||

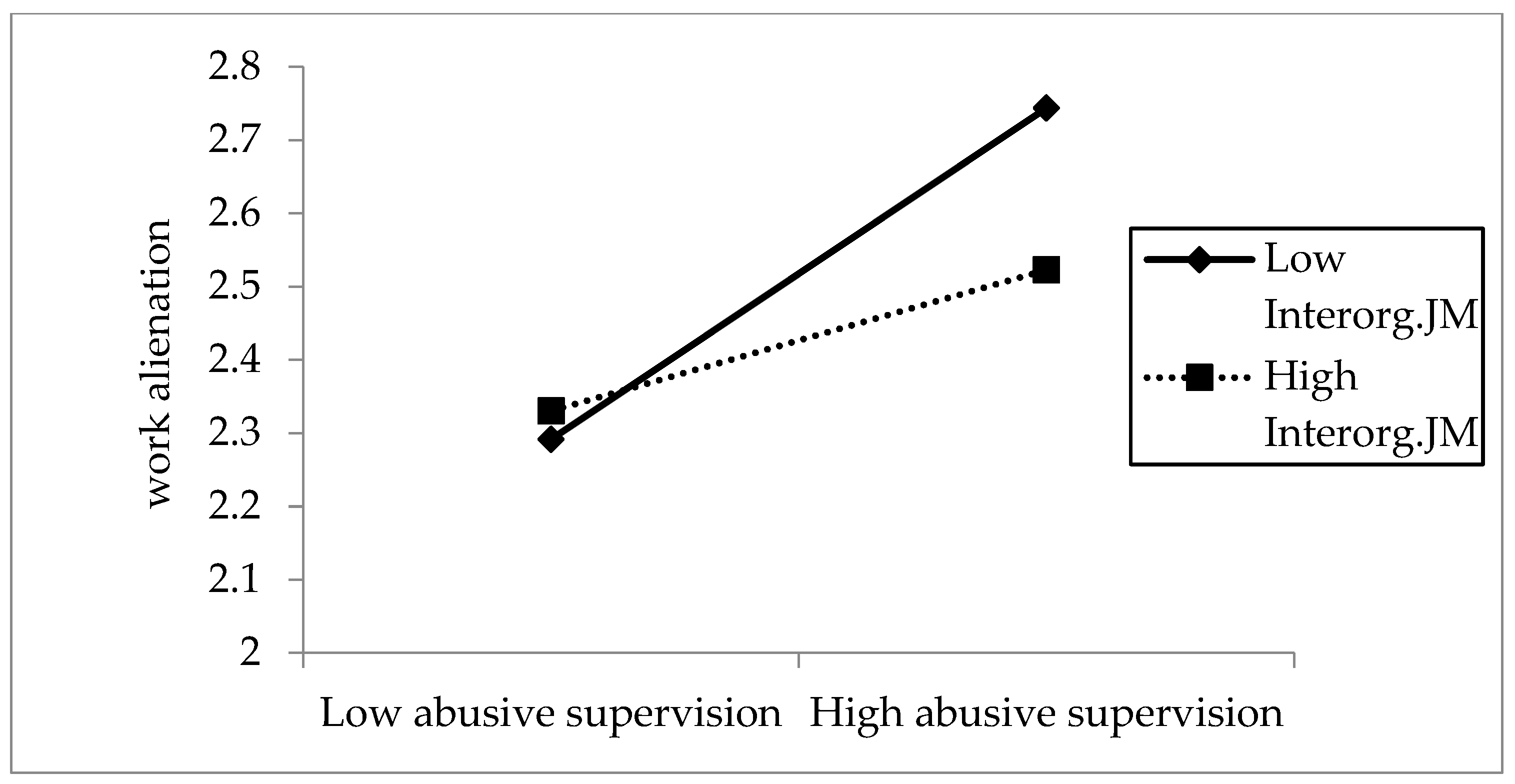

| AS × Interorg.JM | −0.11 ** | −0.14 ** | ||||||

| AS × Intraorg.JM × Pre-focus | −0.06 | |||||||

| AS × Intraorg.JM × Pro-focus | −0.04 | |||||||

| AS × Interorg.JM × Pre-focus | −0.05 | |||||||

| AS × Interorg.JM × Pro-focus | 0.04 | |||||||

| R2 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.19 |

| ΔR2 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| ΔF | 4.14 ** | 22.26 *** | 0.69 | 1.49 | 4.14 ** | 20.09 *** | 6.12 * | 0.61 |

| Variables | Dependent Variable: PWB | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderating Variable: Intraorg.JM | Moderating Variable: Interorg.JM | |||||||

| Model | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| Education | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| Tenure | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Industry | −0.08 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.08 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.03 |

| Work alienation (WA) | −0.19 *** | −0.19 *** | −0.22 *** | −0.20 *** | −0.20*** | −0.25*** | ||

| Intraorg.JM | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | |||||

| Interorg.JM | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | |||||

| Prevention focus (Pre-focus) | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.03 | ||

| Promotion focus (Pro-focus) | −0.09 | −0.09 | −0.07 | −0.08 | −0.09 | −0.06 | ||

| WA × Intraorg.JM | 0.01 | −0.04 | ||||||

| WA × Interorg.JM | −0.03 | −0.07 | ||||||

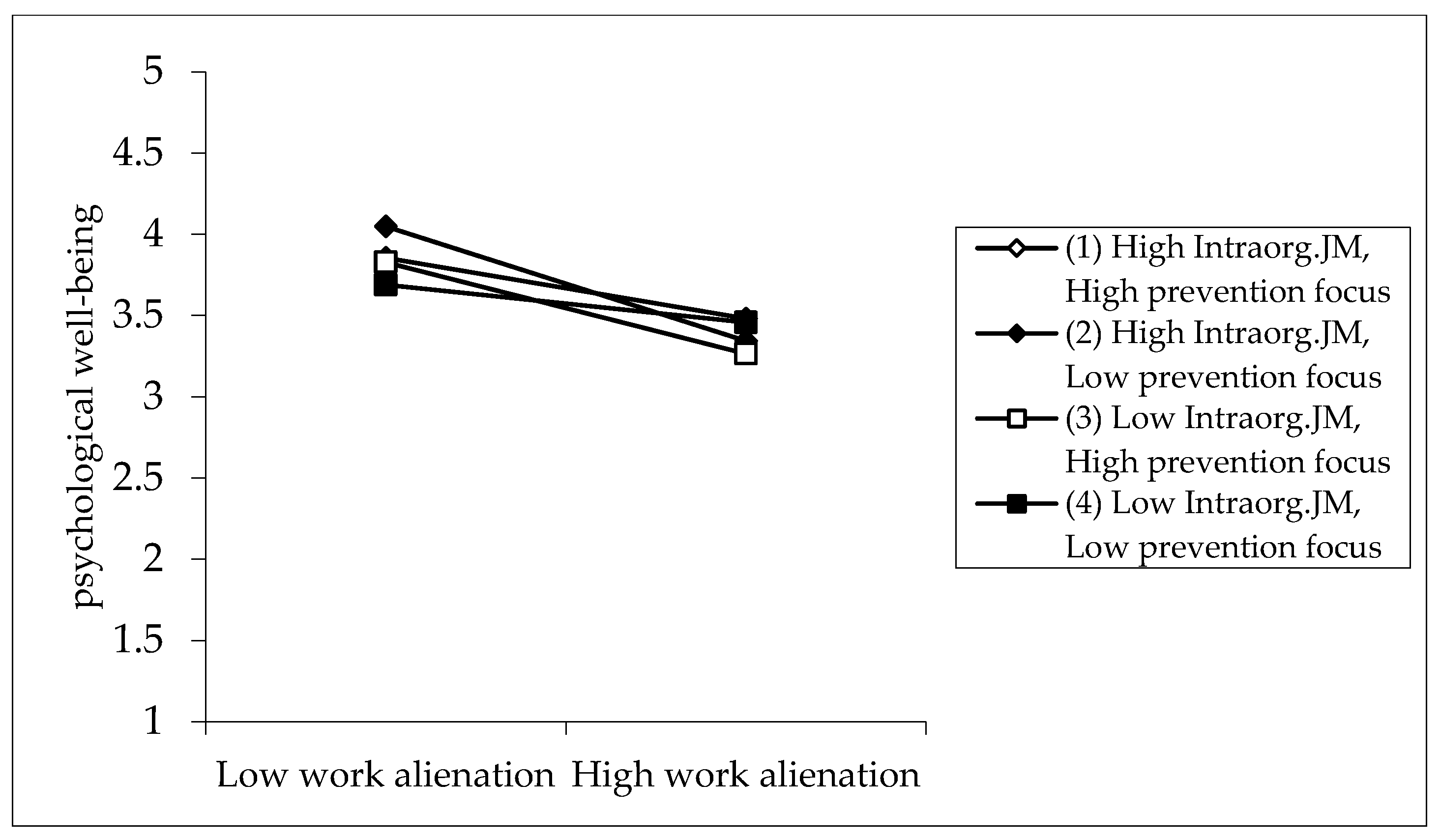

| WA× Intraorg.JM × Pre-focus | 0.14 ** | |||||||

| WA × Intraorg.JM × Pro-focus | 0.08 | |||||||

| WA × Interorg.JM × Pre-focus | 0.09 | |||||||

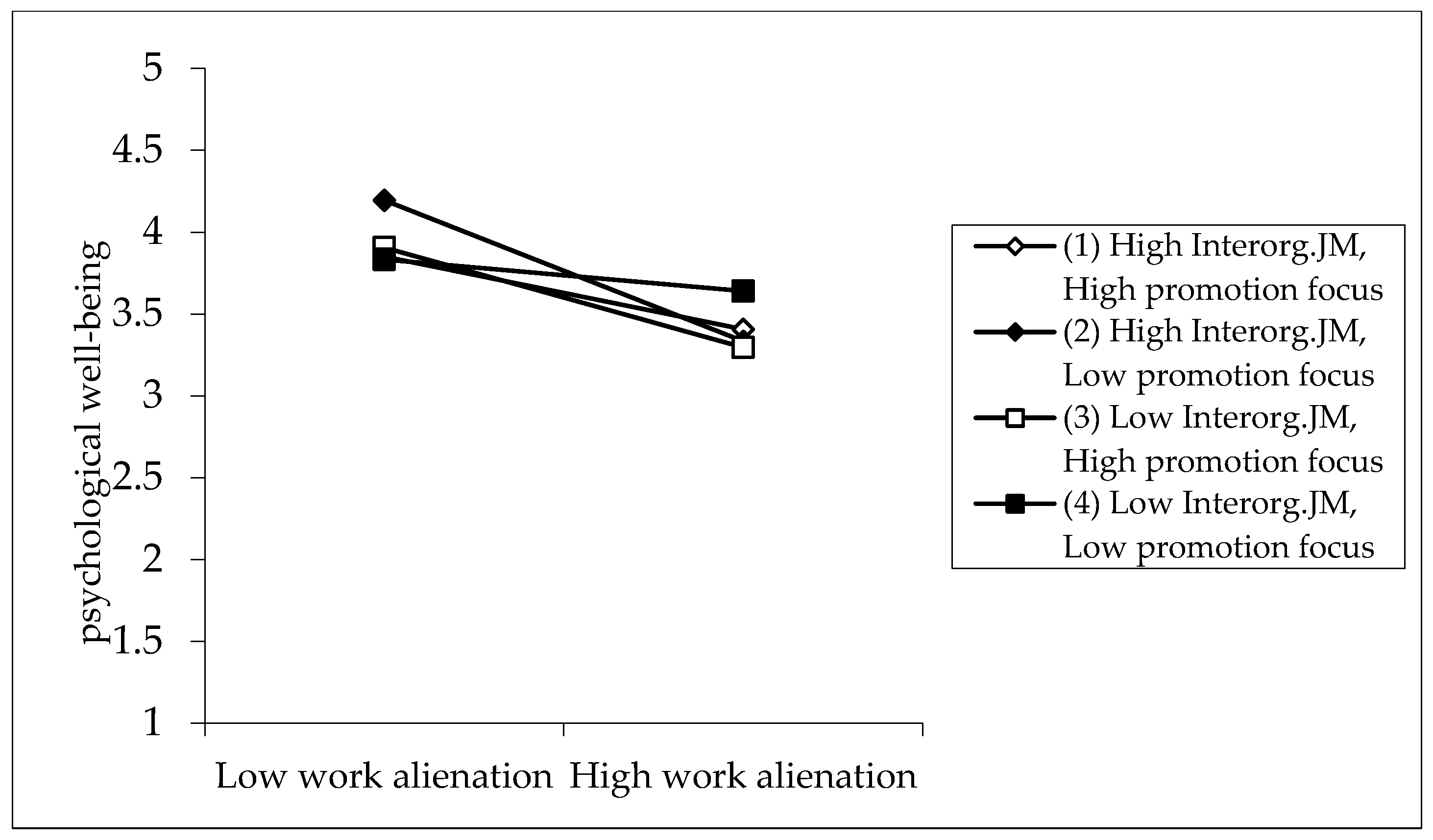

| WA × Interorg.JM × Pro-focus | 0.15 ** | |||||||

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| ΔR2 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| ΔF | 0.81 | 5.09 *** | 0.01 | 5.69 ** | 0.81 | 4.98 *** | 0.49 | 7.28 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Du, X.; Chowdhury, M.S.; Kang, D.-s. Reducing the Negative Effects of Abusive Supervision: A Step towards Organizational Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010019

Du X, Chowdhury MS, Kang D-s. Reducing the Negative Effects of Abusive Supervision: A Step towards Organizational Sustainability. Sustainability. 2023; 15(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Xinqi, Md Sohel Chowdhury, and Dae-seok Kang. 2023. "Reducing the Negative Effects of Abusive Supervision: A Step towards Organizational Sustainability" Sustainability 15, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010019

APA StyleDu, X., Chowdhury, M. S., & Kang, D.-s. (2023). Reducing the Negative Effects of Abusive Supervision: A Step towards Organizational Sustainability. Sustainability, 15(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010019