4.1. Analysis 1: The Effect of Institutional Obstacles on Credit Constraints

First,

Table 1 presents the influence of institutional obstacles on credit constraints in four country groups. Columns (1), (3), (5), and (7) are the results of regressions without the set of control variables (Model 1), and Columns (2), (4), (6), and (8) are the results of Model 2.

Overall, most results show that all four institutional obstacles positively correlate with credit constraints in Models 1 and 2, except for a few special cases. These findings imply that firms are likely to increase their credit constraint as pressures from obstacles increase, such that excessive tax rates, business license administration in government agencies, political instability, and corruption are exacerbated. In particular:

Tax rate: Tax rate constraints exacerbate credit problems in all countries. The correlation coefficients of tax rates are all positive and significant at the 1% level, regardless of the presence of the control variable in the models (except column 2, significance level 5%). Comparing the four types of institutional obstacles, the tax rate barrier has the most substantial impact on increasing the probability of credit restriction, except for the

LI group (Columns 1 and 2). Meanwhile, comparing between countries, the unreasonable tax rate has the most potent effect on credit status in firms of the group

LMI (Columns 3 and 4). This result is consistent with the inferences about the role of state control over business in developing countries. Fisman [

61] and Johnson [

62] pointed out that firms can receive advantages such as tax breaks, credit subsidies, etc., based on political connections. [

63] Kim’s research showed the impact of the relationship between government and firms on corporate tax rates in Southeast Asian companies. Meanwhile, Adhikari [

64] and Derashid [

65] also found evidence that tight government control over the firm is more robust in developing countries. Therefore, firms in these countries are more likely to take advantage of political connections to receive tax favors than in developed countries. In addition, the tax costs of firms are diverse and expensive. In addition to corporate income tax, their other business activities are also subject to national tax (e.g., capital transfer tax, foreign contractor tax, commercial property tax). Tax costs account for more than one-third of total expenses (according to Worldbank’s assessment (

https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/thematic-reports/paying-taxes-2020 (accessed on 5 April 2022)). Therefore, increasing tax rates is likely to reduce the attractiveness of external credits to firms. Its impact might be more potent than other types of institutional obstacles. Countries often use tax rates as an effective tool to gain strategic goals. The government might impose different tax rates on business-oriented groups. For example, Vietnam applies a standard corporate tax rate of 20%. However, in some special cases (such as the oil and gas industry and mining, depending on each project’s location and specific conditions (Article 11 Circular 78/2014/TT-BTC, Law on corporate tax in Vietnam)), the corporate tax rate is 30 to 50%. To encourage new entry firms, firms operating in disadvantaged areas, and those employing many female workers, the government applies a regime that allows taxpayers to enjoy tax incentives or tax reductions. A high tax rate can hinder and even stop a firm’s operation.

Political instability: Political instability almost negatively affects the ability of firms to access credit in groups of countries. In Columns 1 and 5–8, an increase in political instability might be detrimental to firms’ access to finance, as the correlation is positive. Once the political environment becomes prone to instability, it will be the most significant disadvantage for firms in the developed economy (

HI group) in accessing finance. This conclusion supports the view of Roe [

66]. She argued that political factors drive financial market development. A stable, democratic politics can ensure the interests of investors and protect assets for firms. Therefore, political instability creates an inefficient investment environment and many uncertainties in business. In addition, due to the risk of political instability, banks might restrict disbursement to high-risk industries by tightening loan conditions, increasing collateral conditions, etc. As a result, firms’ opportunities to access loans are narrowed [

67]. More interestingly, we find a negative relationship between political instability and credit constraints in the

LMI countries (Columns 3 and 4), but the effect is the opposite for the rest. This result implies that instability in countries

LMI is likely to reduce corporate credit constraints. Dinc [

68] explained that state-owned banks are likely to loosen conditions and increase corporate lending during the election process. In addition, Barro [

69] commented that political instability covers many aspects, such as instability in the government apparatus, political violence, frequent government changes, policies, etc. Therefore, the relationship between political instability may be different if the causes separate the types of instability. In this study, we did not clearly distinguish the types of instability. Despite government ownership being likely to affect the access to capital of firms [

68], the ownership form of credit institutions is also not considered in this study. Therefore, although we cannot provide a definite explanation for the phenomenon in

LMI countries, the results give some confidence in their interactions, similar to the conclusions of Roe [

66].

Corruption: Corruption is not only a leading problem in developing countries or emerging economies. This problem is global and manifests in many different forms. Corruption seriously affects the sustainable development of the economy and society [

70]. In particular, some researchers believe that corruption reduces competitiveness and distorts the nature of trade [

71]. Therefore, a country with a high rate of corruption is often unattractive to foreign investors and domestic investors. As a result, the domestic economy cannot afford to face difficulties caused by integration and free trade. Moreover, according to Olken [

72], the manipulation of bribe-takers in the state management apparatus makes the rights and interests of business entities infringed. Over time, it weakens a country’s institutional system. However, this research did not find out a relationship between corruption and credit constraints in the

LI group (Columns 1 and 2) (as the correlation coefficients are significant at a level of more than 10%). Corruption is likely to increase by 4.8% (Column 4) the probability of credit constraints in the

LMI group. For the model without control variables, the impact of corruption on credit constraints is less than insignificant (0.3%, Column 3). This finding aligns with Wellalage’ study [

73] that in five South Asia countries including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Pakistan in 2014 (According to the World Bank’s 2020 National Income Classification, Afghanistan is

LI country, the remaining four countries are

LMI countries

Appendix A. However, the number of observed firms in Afghanistan only account for 3.77%. Thus, these findings can represent the

LMI group). The results showed that corruption increases the probability of credit constraints by almost 8%. The impact of corruption was most significant in the

HI group. The probability of a credit constraints can increase by 9.3% (Column 8) when a business has a corruption problem. This is almost five times higher than the impact of this barrier in the

UMI group (Column 5—correlation coefficient 0.019). These findings are consistent with some previous views, such as Meon [

74] and Shleifer [

75]. The authors supported the view that corruption poses a major disadvantage to business development, especially access to finance. In addition, our findings are consistent with the hypothesis of Avnimelech [

76]. Based on Huntington [

77] and Leff [

78], Avnimelech argued that corruption increases the cost of borrowing and creates a negative assessment of the stable development of the market. Therefore, it negatively impacts firms’ need to enter and expand the market. This conclusion implies that firms may experience a reduced need for loans due to psychological effects caused by corruption, even though they still have demand. In addition, Avnimelech found evidence that doing business in developed countries is particularly sensitive to corruption. The negative impact of corruption in developed countries is twice that of non-developed countries. Therefore, our results imply that anti-corruption is essential for every country. However, high-income countries should have stricter measures focused on reducing the negative effects of corruption.

Business Licensing and Permit: Our study finds evidence about the effect of a business licensing on accessing external credit, except for firms in the

UMI group (Columns 5 and 6). Columns 2 and 4 show that when firm characteristics are controlled, business licensing obstacles are likely to increase the probability of credit constraints in

LI and

LMI groups, 4.7% and 4.8%, respectively. These findings are consistent with several previous studies. Shleifer [

79] demonstrated that the law, regulations, and conditions are all critical to the size and extent of capital markets. Therefore, the enforcement of laws and administrative procedures can affect the willingness to lend and the ability to access credit. Similarly, Skosples [

80] emphasized that the regulations about establishment and closure in transition economies negatively influence bank lending decisions. The author argued that the overlapping regulations and the legal inefficiency directly affect the disposal of bank collateral if the loan is not reimbursed. In the

HI group, the impact of this obstacle is more significant. In particular, the probability of credit constraints is likely to increase by 6% (Column 7) when firms face difficulties with a business license and permit. However, differences in firm and owner characteristics emerge (Column 8), suggesting that firms find it harder to access credit when they face this barrier, as the probability of credit constraints increases by 7.9%.

Although the results indicate that if the government introduces strict and complicated procedures for licensing, it can be detrimental to firms in accessing formal loans. To increase their chances of receiving healthy credit, restructuring the legal process, removing cumbersome regulations, and strengthening the legal framework are necessary. However, this recommendation does not mean that all barriers need to be removed. Although it can create favorable conditions for firms, removing barriers poses many risks to credit institutions and the economy. For example, minimum capital provisions for the issuance of business licenses, export licenses, certificates related to collateral, origin, etc., are necessary to guarantee loan repayment. Therefore, a reasonable regulatory framework and proper licensing procedures are needed rather than repealed.

Moreover, the negative correlation coefficient of control variables also supports the previous hypothesis. The results show that it is easier for exporting firms to obtain loans than domestic ones. In addition, firm size is also correlated with access to credit. In addition, the significant negative relationship between a firm’s age and credit restriction implies that long-standing firms have more advantages than young ones regarding access to credit. Beck [

53] determined that older and larger firms are associated with better management capacity, more collateral choices, and high reputation. These are positive factors that determine the credit-worthiness of the firm. Therefore, large and older firms are more likely to access credit than young and small-scale firms [

81,

82].

In addition, possessing international certifications means that the firm is recognized for quality and reputation. Therefore, international certification can create favorable conditions for firms to access external funding. Nevertheless, the coefficient between innovation, foreign ownership, and credit constraint is insignificant (

p > 0.1). The results indicate that firms located in large cities of middle-income countries (

LI and

HI) might access credit more easily. This finding is the opposite of firms in

LMI countries. As pointed out by Lee [

83], geographic location significantly affects credit status. The author believed that the city’s geographical size is associated with economic advantages. He surveyed 97 countries and found that large cities—more than 1 million inhabitants—facilitate access to finance better than other cities because firms located in the big city receive more opportunities to access advanced facilities, increase network connectivity, and increase professional training [

84]. Some scientists, such as Brambor [

85] and Martin [

86], argued that the geographical gap would gradually disappear due to the growing digital science. However, the empirical results show that the influence of geographical location on the development of financial markets and firms cannot be denied, especially in developed countries.

In brief, all four mentioned institutional obstacles affect the firm’s credit status in the HI and LMI groups. Meanwhile, corruption in the least developed countries (the low-income nation—LI) does not seem to correlate with access to credit. In addition, the excessive control of administrative procedures such as the business licenses and permits aggravates the firm’s limited credit situation, except for the UMI group. Finally, the impact of political stability is different across country groups.

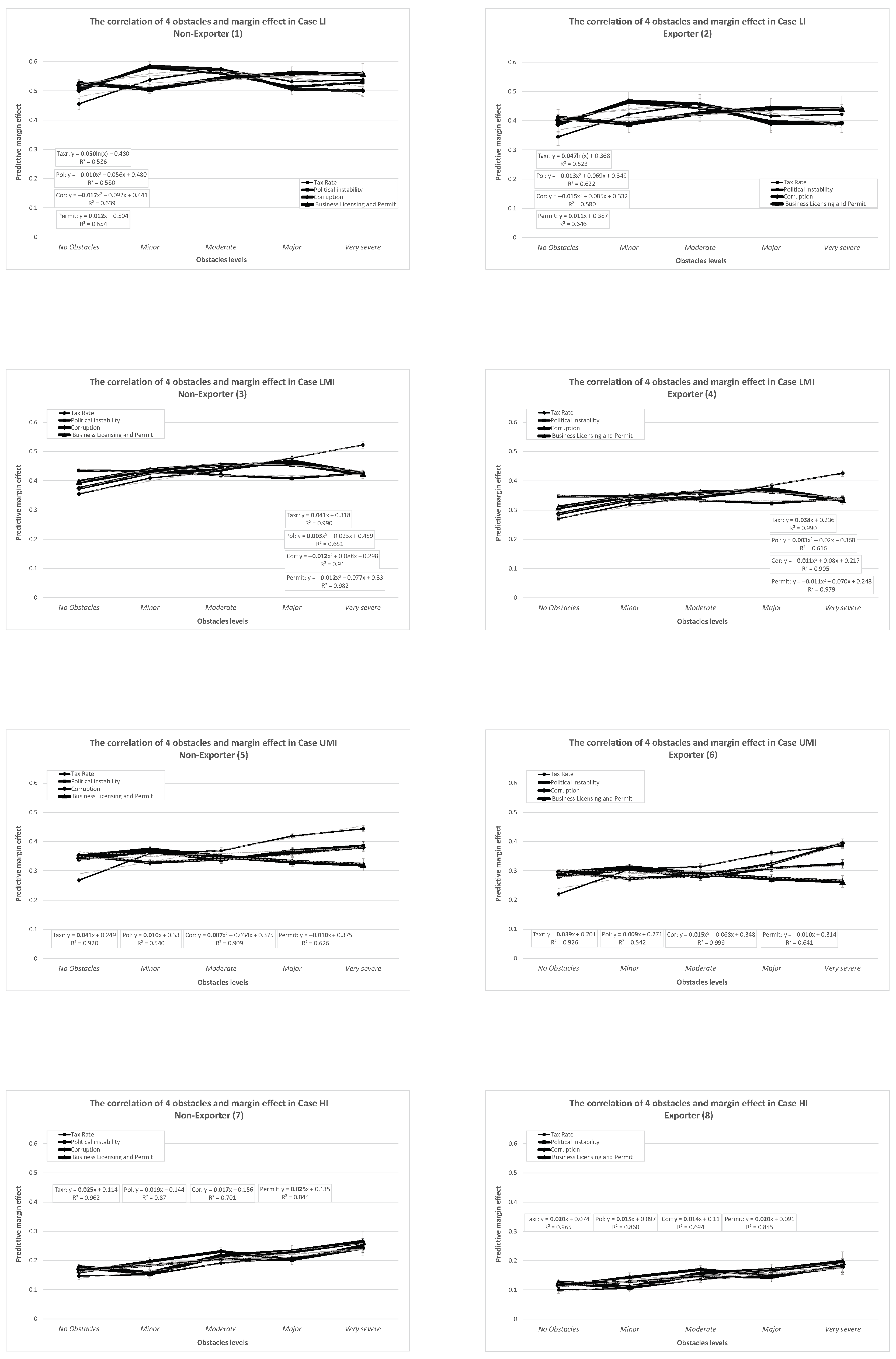

In the second step, we predict the margin effect of the obstacles levels for credit constraints. Then, we compare non-exporters and exporters to further assess the impact of each perceived level obstacle on credit constraint.

Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the marginal effect of obstacles on credit constraints at the 95% confidence interval, compared between four groups of countries. In general, firms’ perceptions of barriers have a significant marginal effect on credit constraints. At first glance, the charts of the two groups by export status do not reflect a stark difference. The results found heterogeneity in the trend of the impact of constraints on credit restriction in the

LI,

LMI, and

UMI groups. However, the image of the

HI group showed a similar effect of the hindrances. An exciting feature is that in the first two groups (

Figure 1(1–4)), the impacts of all types of obstacles on non-exporters across all levels are significantly higher than those of exporters. Meanwhile, there is little difference between the two groups by export in the rest of the countries (

Figure 1(5–8)). Numerous previous empirical studies scrutinized a correlation between institutional quality and economic growth. Easterly [

24] argues that underdeveloped countries in Africa are characterized by weak institutional frameworks, poverty, and backwardness. In addition, Hall [

87] and Easterly [

88] found that countries with better institutions are often associated with high

GDP per capita. This impact mechanism is explained through the growth of

FDI investment and the speed of opening of the economy. The above arguments imply that efficient institutions often characterize developed countries. Therefore, discrimination between firm groups is narrowed. This hypothesis suggests that institutional obstacles to credit constraints are nearly the same in all firm groups, regardless of export status.

In more detail, the relationship between tax rate and the probability of the credit constraint is predicted as a positive linear function, with

being more than 92%, except in the

LI group. Access to credit becomes increasingly disadvantageous as tax barriers become more severe for firms. The results show that the marginal effect of tax rates is most substantial in medium-developed countries (

LMI and

UMI groups) and lowest in developed countries (

HI groups). The proof is that the histogram increases steadily with a smaller amplitude in the

HI group, compared to the other groups. Although the tax rate impact is predicted to be a saturation function in

LI countries (

Figure 1(1,2)), the coefficient of determination is only about 50%. This value of

might suggest that the tax rate association explains only about 50% of the differences in credit restriction between individuals. This implication can lead to doubts about the appropriateness of the model. However, after testing the model prediction with other functional forms such as linear, polynomial, etc., the saturation function seems most suitable. The trendlines are predicted as polynomial functions for the remaining three barriers. The cubic function is predicted to be suitable for the group of emerging countries (

LI), and the polynomial of order 2 is ideal for the group of

LMI.

In contrast, in more prosperous countries (

UMI and

HI), the majority conforms to the linear functional form (except for corruption in

UMI countries). In the

LI countries, the impact of political instability and corruption on the margin effect of credit constraints is similar for both exporting and non-exporting groups (

Figure 1(1,2)). The most explicit disparity in the marginal impact of credit constraints is between the No Obstacles and Minor levels. The marginal effect of credit constraints increased sharply before trending down at subsequent levels of barriers. The result then tends to become saturated.

The marginal effect of credit constraints decreases once firms move from a perception of no obstacles to a perception of a mild impediment to business licensing restrictions. After that, this marginal effect tends to increase significantly before saturating at the Major level. For the (

LMI group of countries (

Figure 1(3,4)), the predicted trend lines are mainly polynomials of order two, where corruption and permit are concave functions. Higher levels of national corruption and tight policy regulation increase the expected marginal and peak near 0.5 when the barrier is Major level.

In

UMI countries (

Figure 1(5,6)), the marginal effect of corruption is predicted to be a convex quadratic polynomial. As the level of corruption gradually moves from low corruption (Minor) to higher levels, it increases the margin effect on credit restriction. However, the graph is steeper for exporters (

Figure 1(6)) compared to domestic firms (

Figure 1(5)). Instead of fluctuating as much as other groups, in the prosperous country group (

HI), institutional weakness affects credit constraints and is predicted as a linear function.

Thus, it can be seen that under the influence of different country characteristics (different average income), the impact of some unfavorable institutional features has a different effect on accessing credit. Hence, the graphs showing the marginal impact in each country group can be described by different functional forms. The graphs fluctuate more strongly in poorer countries. These results suggest that policymakers in emerging countries might clean up the morality of the government apparatus, restructure legal processes, etc., to limit the adverse effects of a weak institutional system. The government should offer more tax support policies (tax reduction, tax return support, and stricter tax management) to create favorable conditions for firms’ development.

In the third step,

Table 2 summarizes the regression results in the robustness test. The credit constraints is measured by a qualitative method. Overall, all regression coefficients are statistically significant at the 1% level. In addition, all four institutional obstacles have a positive relationship with credit constraints. In other words, an increase in the perception of institutional obstacles can increase the likelihood of perceived financial limitations. In addition, regardless of controlling for firm-specific variables, the results did not change significantly. These findings support the main regression results (shown in

Table 1).

However, the level of institutional impact on firms’ access to finance is stronger than the quantitative credit constraints. For example, in

LI countries—Column 1—the marginal effect of the business licensing barrier on the alternative credit constraint is 0.230, which is four times higher than on the original credit constraint (Column 1,

Table 1). In addition, according to these qualitative credit constraints, the impact of licensing barriers is more pronounced. This barrier has the most substantial influence compared with the remaining obstacles (except for the

UMI group). In addition, the effect of control variables is not different from the results in

Table 1.

In conclusion, access to credit is governed by an institutional framework in every country. A weak institutions inhibits firms’ opportunities to access finance. Furthermore, the firm’s characteristic contributes to this negative. These results suggest that developing countries should build a more affordable tax system for small firms. Additionally, governments need to maintain political stability and clean up bureaucracy. Importantly, this is not only necessary for poor and emerging countries. The effects of political instability and corruption are also evident in prosperous economies. The cumbersome and redundant legal procedures are barriers to the development of enterprises. Therefore, restructuring the management and licensing mechanism is essential to support enterprises in accessing capital. Finally, the establishment of mechanisms and policies to help SMEs and firms in remote areas are also measures to consider to reduce their difficulty in accessing financial resources.

4.2. Analysis 2: The Linkage between Credit Constraints and Export Decision

The endogenous tests is performed and presented in

Table 3. The Hausman test results reveal that

and is significant with

. This result confirms the existence of the endogenous phenomenon and, at the same time, shows that the selected instrumental variable meets the requirements that there is no correlation with the residuals of the original regression model. Therefore, it has successfully overcome the endogenous phenomenon caused by the credit constraint variable. This conclusion is strongly supported by the results of the LM-statistic and the Cragg–Donald–Wald

F-statistic because the results of these two tests are significant with

. In summary, these tests provide evidence to confirm that the instrumental variable is valid and has adequate power in mitigating the endogeneity problem.

Then,

Table 4 summarizes the effects of credit constraints and control variables on exports with and without controlling institutional obstacles. Overall, the findings show a negative impact of credit constraints on firms’ exports to international markets. However, these adverse effects tend to increase with the wealth of countries. Looking at the group of lowest-income countries (Column 1), we find no relationship between credit constraints and export status. Weak institutions can increase uncertainty and the cost of trade, leading to underperforming markets [

89]. Consequently, firms in poor and emerging countries are more dependent on institutional quality [

90]. This robust dependence might be why removing institutional obstacles from the model is inappropriate. After further examination of institutional specifications, Column 2 shows the negative outcome of credit constraints. Under institutional obstacles, firms that struggle to access credit might reduce their ability to participate in exports by 4.6%. These firms seem to be affected only by tax rates and licensing procedures. The interaction between exports and the other two types of institutions, including political instability and corruption, was not statistically significant. This result evokes contemplation because, according to Olken [

72], corruption and instability are severe problems in underdeveloped and developing countries.

On the other hand, North [

45] argued that the impact of informal institutions is more significant in weak economies. In addition, informal funding is the most common for small-size firms. However, in the framework of this study, only formal credits are considered. This is why the results in this group were not as expected.

Despite the institutional obstacles, credit constraints presumably affect their ability to participate in international markets in the remaining three groups. This findings align with Muuls [

1], Manova [

91]. Under institutional interaction, credit-restricted firms are likely to reduce the probability of firms exporting in

LMI and

UMI countries by 8.1% (Column 4) and 6.6% (Column 6), respectively. These negative effects were more severe in the

HI group. In particular, the probability of exporting is likely to be reduced by approximately 20% (Column 8) when enterprises have difficulty accessing capital.

The set of control variables contributes significantly to explaining the relationship between credit constraints and export probability. Foreign-invested enterprises create favorable conditions for export development, especially in

LMI countries. International certificate holdings and innovation tend to have a substantial impact on the export probabilities in the least developed economies (group

LI) and medium developed countries (groups

LMI and

UMI). Similar to Bilkey [

92], firm size has a positive effect on the ability to export. Large firms tend to export more easily than small firms. Freeman [

93] believed that geographical location in large-scale cities creates many development opportunities for firms. Although the competition here can be fierce, challenges always come with opportunities if firms take advantage and develop efforts [

94]. Therefore, these difficulties push firms to improve products, human resources, and management. Investments in big cities can support firms to export. However, headquarters located in big cities do not seem to bring export advantages in other countries

LMI).

In a nutshell, this study shows that credit restriction reduces the likelihood of international market entry. Furthermore, the export disadvantage is exacerbated by institutional constraints in the LI and LMI countries. Since specifications characteristics are different across country groups, the effect of institutional obstacles and credit constraints on export status is thus different across groups.

Next,

Table 5 reports the results in the further analysis when each institutional obstacles are considered separately. From the comparison between groups by institutional obstacles status, the nexus between credit constraints and exports is elucidated. In general, once each institutional obstacle is considered separately, the interaction of each institutional obstacle on the relationship between credit status and exports is more pronounced. Institutional obstacles significantly moderate the relationship between credit constraints on firms’ export status in

LMI,

UMI, and

HI groups, except for a few cases. However, for low-income countries, this interaction does not explain the likelihood of a firm entering the international market.

Panel A shows that in countries with an unreasonable tax rate framework (Column 2) and cumbersome licensing procedures (Column 8), easy access to credit creates an export advantage for firms. Particularly, credit-constrained firms are likely to reduce their export probabilities by 2.3% when they also face a tax rate obstacle. Meanwhile, the export probability doubled (4.7%) when that firm encountered obstacles in business licensing and permits. However, political instability and corruption cannot moderate the relationship between credit restrictions and exports, as the correlation coefficients were not statistically significant. This result was predictable, as the relationship between political instability, corruption, and credit constraints was not found in

Table 1.

Panel B reflects the negative outcome of credit constraints in the

LMI group. The difference in the impact of each institution type on the relationship between credit restrictions and exports is almost negligible. Particularly, for firms that suffer in business licenses (Column 8), credit constraints are likely to reduce their probability of entering the international market by 5.8%. Meanwhile, this figure is 5.6% (Column 2) for firms facing tax rate obstacle, 5.5% and 5.4% for the other two types of obstacles (Columns 4 and 6). These results support for Bernard’s study [

39]. Firms wishing to enter export markets or expand exports may have more substantial capital requirements. These firms need to borrow more to meet their capital needs. As a result, they might struggle once rejected or only receive partial credit. Even in the case of non-credit constrained firms, the correlation coefficient of credit constraints is found to be significant. However, the presence of obstacles alleviates this negative impact. Among institutional constraints, the interaction of corruption is most effective. Specifically, credit constraints have negative impacts even in healthy institution conditions (Column 5—the probability of export decreases 17%). However, under the influence of corruption, access to credit has the weakest effect on export probability (Column 6—the probability of export decreases 5.4%). This finding supports Klapper [

95]. He argued that in developing countries or where corruption is high, bribery could help firms clear up obstacles. He found the adverse effects of institutional barriers on the opportunities for firms to enter foreign markets in countries with low corruption rates. However, the regulatory obstacles have not reduced the number of firms entering the market.

Panels C and D reflect the negative results in the UMI and HI groups. The responses to export decisions when firms face credit constraints and institutional obstacles are pretty similar between these two country groups (except for the results of political instability). In particular, our results do not find a relationship between credit constraints and exports in both groups for firms with or without institutional constraints (Columns 1, 5, and 7). Meanwhile, credit constraints reduce the firm’s favorable to export (Columns 2, 6, and 8). However, the results recorded in the HI group were nearly three times more robust than in the UMI group. Typically (Column 2), the export probability in the HI group is likely to be reduced by 28.8% due to credit constraints, which is three times higher than that of counterparts in UMI group (7.5%). These findings emphasize the importance of institutional issues in business operations. The healthy institution almost eliminated the adverse effects of credit constraints. However, when the institution begins to show weakness, inconsistency, and transparency, the disadvantages caused by credit restrictions are recognized. In a weak institution, the ability to participate in international markets is reduced when firms have difficulty accessing finance.

In summary, obstacles clustering has provided some very significant results. Regardless of institutional obstacles, for firms in LMI group, difficulty accessing credit is a barrier to exporting. For the rest of the countries. However, the findings indicate that credit constraints only really affect exports when institutional obstacles are controlled in the model.

In the further analysis,

Table 6 presents all findings in two group by firm size. Overall, the negative consequences of credit constraints on international trade are evident. Regardless of the firm size, available external finance is an advantage for firms to enter the export market.

Columns 1 and Column 3 report the findings from Model 3. The variable of major interest is credit constraints, which negatively affect the ability to enter the export market of

SMEs and large-sized firms, by 16.3% and 10.6%, respectively. These findings are not inconsistent with those of Pietrovito’s study [

96]. They found that credit constraints reduced the export advantage of

SMEs. An

SME with easy access to finance is 2.5% more likely to be an exporter than an

SME with limited credit. Pietrovito’s study covered 65 emerging and developing countries from 2003 to 2014. In comparison, our research uses a broader dataset and covers 131 countries over the recent period. This reason might explain why our coefficient is more considerable.

Columns 2 and 4 report the results from regression Model 4. Under the participation of four explanatory variables representing institutional obstacles, the correlation coefficient obtained in both groups is not much different. However, it is worth noting that the weakness of institutions makes the effect of credit constraints on exports stronger (from 16.3% to 16.6%). In addition, SMEs are negatively affected by inconsistencies, cumbersome mechanisms, corruption, and political instability. Meanwhile, we only find the impact of corruption on the export status of large firms at the 10% significance level. When large enterprises face institutional constraints, credit-constrained firms reduce the probability of exporting by 0.1% compared to their counterparts.

In addition, a firm’s characteristics also contribute to the impact on the firm’s ability to export, regardless of firm size. Firm age is particularly significant for

SMEs. As previously argued by Beck [

53] and Shinkle [

97], it is difficult to export for a small and young firm located in small cities. Furthermore, innovation and experience also play essential roles in explaining export advantages.

In summary, Analysis 2 was carried out to find the relationship between credit constraints and export and the role of institution obstacles in this linkage. The findings show that firms’ access to capital negatively affects exports in all regions. The results in the group of rich countries are most pronounced. In addition, institutions’ health exacerbates the impact of credit restrictions on exports. Firms that operate in weak institutions are also less likely to participate in exports. Moreover, SMEs suffer the consequences of credit constraints more clearly than large-sized firms. In addition, this is also a vulnerable group of firms in a weak institution.