Self-Efficacy as a Mediator of the Impact of Social Capital on Entrepreneurial Orientation: A Case of Dayak Ethnic Entrepreneurship

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Developments

2.1. Social Capital (SC) and Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO)

2.2. Self-Efficacy as a Mediator

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Validity Tests

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goel, G.; Rishi, M. Promoting entrepreneurship to alleviate poverty in India: An overview of government schemes, private-sector programs, and initiatives in the citizens’ sector. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2012, 54, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Enterprise UK. Think Global Grade Gocial. 2015. Available online: https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/seuk_british_council_think_global_report.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Hill, S.; Ionescu-Somers, A.; Coduras, A.; Guerrero, M.; Azam Roomi, M.; Bosma, N.; Sahasranamam, S.; Shay, J. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2021/2022 Global Report: Opportunity Amid Disruption; GEM: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, P.H.; Aldrich, H.E. Social Capital and Entrepreneurship. Found. Trends Entrep. 2005, 1, 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, S.S.; Mohd, R.; Kamaruddin, B.H.; Nor, N.G.M. Personal values and entrepreneurial orientations in Malay entrepreneurs in Malaysia: Mediating role of self-efficacy. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 2015, 25, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1986, 4, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Greene, P.G.; Crick, A. Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? J. Bus. Ventur. 1998, 13, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Stajkovic, A.D.; Ibrayeva, E. Environmental and psychological challenges facing entrepreneurial development in transitional economies. J. World Bus. 2000, 35, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Tuning in, tuning out: The strange disappearance of social capital in America. PS Polit. Sci. Politics 1995, 28, 664–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Altinay, L. Social embeddedness, entrepreneurial orientation and firm growth in ethnic minority small businesses in the UK. Int. Small Bus. J. 2012, 30, 3e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, Z. The effect of social capital on White, Korean, Mexican and Black business owners’ earnings in the US. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2008, 34, 955–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFC. UKM Yang Dimiliki Wanita di Indonesia: Kesempatan Emas Untuk Institusi Keuangan Lokal; IFC: Frankfurt, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- GEDI. Entrepreneurship and Business Statistics. Available online: https://thegedi.org/global-entrepreneurship-and-development-index/ (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Joshi, L.; Wijaya, K.; Sirait, M.; Mulyoutami, E. Indigenous Systems and Ecological Knowledge among Dayak People in Kutai Barat, East Kalimantan—A Preliminary Report; ICRAF Southeast Asia Working Paper, No. 2004_3; ICRAF: Bogor, Indonesia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sugianto, H.R.T.; Vasantan, P. Spiritual Capital in Entrepreneurial Spirit of Dayak Youth. KnE Soc. Sci. 2018, 616–624. [Google Scholar]

- Tateh, O.; Latip, H.A.; Awang Marikan, D.A. Entrepreneurial intentions among indigenous Dayak in Sarawak, Malaysia: An assessment of personality traits and social learning. Macrotheme Rev. 2014, 3, 110–119. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M.S. Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.R.; Miller, C. “Class Matters”: Human and Social Capital in the Entrepreneurial Process. J. Soc. Econ. 2002, 32, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.E.; Zimmer, C. Entrepreneurship through Social Networks. In The Art and Science of Entrepreneurship; Sexton, D., Smilor, R., Eds.; Ballinger: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Lee, K.; Pennings, J.M. Internal capabilities, external networks, and performance: A study on technology-based ventures. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 615–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpham, T.; Grant, E.; Thomas, E. Measuring social capital within health surveys: Key issues. Health Policy Plan 2002, 17, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcuello-Servos, C. Networks, trust and social capital: Theoretical and empirical investigations from Europe. Int. Sociol. 2007, 22, 200–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S.W. Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, V.M.; Sorenson, D.; Henchion, M.; Gellynck, X. Social capital and knowledge sharing performance of learning networks. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Welsch, H. Social Capital and Entrepreneurial Growth Aspiration: A Comparison of Technology and Non-technology Based Nascent Entrepreneurs. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2003, 14, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P.; Honig, B. The Role of Social and Human Capital Among Nascent Entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 301–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollinger. Entrepreneurship: Strategies and Resources; Austen Press: Irwin, IL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, W.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, and value creation: The role of intrafirm networks. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 464–478. [Google Scholar]

- Stam, W.; Elfring, T. Entrepreneurial orientation and new venture performance: The moderating role of intra-and extra industry social capital. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Stanton, B.; Gong, J.; Fang, X.; Li, X. Personal Social Capital Scale: An instrument for health and behavioral research. Health Educ. Res. 2009, 24, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.L. Entrepreneurial network and new organization growth. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1995, 19, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Gully, M.S.; Eden, D. General self-efficacy and self-esteem: Toward theoretical and empirical distinction between correlated self-evaluations. J. Org. Behav. 2004, 25, 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Locke, E.A.; Collins, C.J. Entrepreneurial motivation. Human Res. Manag. Rev. 2003, 13, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Gully, S.M.; Whiteman, J.A.; Kilcullen, B.N. Examination of relationships among trait-like individual differences, state-like individual differences, and learning performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 835–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Gully, S.M.; Eden, D. Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Org. Res. Methods 2001, 4, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Erez, A.; Bono, J.A. The power of being positive: The relation between positive self- concept and job performance. Human Perform. 1998, 11, 167–187. [Google Scholar]

- Salancik, G.R.; Pfeffer, J. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978, 23, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, D. The Attraction Paradigm; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Clore, G.L. Interpersonal Attraction: An Overview; General Learning Press: Morristown, NJ, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Social Comparison Processes. Human Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannadhasan, M.; Charan, P.; Singh, P.; Sivasankaran, N. Relationships among social capital, self-efficacy, and new venture creations. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, D. Entrepreneurial Behavior; Scott Foresman and Co.: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, N.G.; Vozikis, G.S. The influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1994, 18, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, G.D.; Balkin, D.B.; Baron, R.A. Inventors and new venture formation: The effects of general self-efficacy and regretful thinking. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2002, 27, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd, R.; Kamaruddin, B.H.; Hassan, S.; Muda, M.; Yahya, K.K. The important role of self-efficacy in determining entrepreneurial orientations of Malay small scale entrepreneurs in Malaysia. Int. J. Manag. Stud. 2014, 21, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd, R.; Kirana, K.; Kamaruddin, B.H.; Zainuddin, A.; Ghazali, M.C. The mediatory effect of self-efficacy on the relationship between religious values and entrepreneurial orientations: A case of Malay owner managers of SMEs in manufacturing industry. Proced. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 130, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- International Test Commission. The ITC Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests, 2nd ed.; ITC: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mayasari, M.S.; Tulistyantoro, L.; Rizqy, M.T. Kajian Semiotik Ornamen Interior Pada Lamin Dayak Kenyah (Studi Kasus Interior Lamin Di Desa Budaya Pampang). Intra 2014, 2, 288–293. [Google Scholar]

- Hadibrata, W. Musik Sampek Sebagai Kemasan Wisata Di Desa Pampang Samarinda Kalimantan Timur. Ph.D. Thesis, Institut Seni Indonesia, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Richman, W.L.; Kiesler, S.; Weisband, S.; Drasgow, F. A meta-analytic study of social desirability distortion in computer-administered questionnaires, traditional questionnaires, and interviews. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 754–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, J.M. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, D.L.; Lane, M.D. Individual entrepreneurial orientation: Development of a measurement instrument. Educat. Train. 2012, 54, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tapsell, P.; Woods, C. Potikitanga: Indigenous entrepreneurship in a Maori context. J. Enterp. Commun. People Places Glob. Econom. 2008, 2, 192–203. [Google Scholar]

- Rahdari, A.; Sepasi, S.; Moradi, M. Achieving sustainability through Schumpeterian social entrepreneurship: The role of social enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 137, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, J.G.; Venkataraman, S. The entrepreneur environment nexus: Uncertainty, innovation, and allocation. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velath, S. Social Entrepreneurs are Vital to the Achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. Available online: https://medium.com/change-maker/socialentrepreneurs-are-vital-to-the-achievement-of-the-un-sustainable-development-goals-by2030-aa9f579466c1 (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Martin, R.L.; Osberg, S.R. Getting Beyond Better: How Social Entrepreneurship Works; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Widjojo, H.; Gunawan, S. Indigenous tradition: An overlooked Encompassing-Factor in social entrepreneurship. J. Soc. Entrep. 2020, 11, 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crevello, S. Dayak land use systems and indigenous knowledge. J. Hum. Ecol. 2004, 16, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Windt, R. The Synergy Between Social Entrepreneurship, Community Empowerment and Social Capital for the Local Economic Development of the Smallholder Rubber Culture in Central Kalimantan. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Peredo, A.M.; Chrisman, J.J. Toward a theory of community-based enterprise. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sada, C.; Alas, Y.; Anshari, M. Indigenous people of Borneo (Dayak): Development, social cultural perspective and its challenges. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2019, 6, 1665936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, G.; Saks, A.M.; Hook, S. When success breeds failure: The role of self-efficacy in escalating commitment to a losing course of action. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 1997, 18, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainudin, M.; Hadi, C.; Suhariadi, F. Student Entrepreneurial Intention towards Entrepreneurship Course with Different Credit Loading Hours. Int. J. Entrep. 2019, 23, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M.Y.; Chan, W.S.; Mahmood, A. The effectiveness of entrepreneurship education in Malaysia. Educ. Train. 2009, 51, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Yunanto, Y.; Suhariadi, F.; Yulianti, P.; Andajani, W. Creating Social Entrepreneurship Value for Economic Development. Prob. Perspect. Manag. 2021, 19, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, L.; Orlikova, M. Social entrepreneurship and social enterprises: The case of Slovakia. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Innovation Management, Entrepreneurship and Corporate Sustainability (IMECS 2016), Prague, Czech Republic, 26–27 May 2016; pp. 495–505. [Google Scholar]

- Mura, L.; Kajzar, P. Small Businesses in Cultural Tourism in a Central European Country. J. Tour. Serv. 2019, 10, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larasatie, P.; Fitriastuti, T.; Yovi, E.Y.; Purnomo, H.; Nurrochmat, D.R. COVID-19 Anxiety as a Moderator of the Relationship between Organizational Change and Perception of Organizational Politics in Forestry Public Sector. Forests 2022, 13, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larasatie, P.; Setiowati, S. From Fingerprint to Footprint: Using Point of Interest (POI) Recommendation System in Marketing Applications. Asian J. Technol. Manag. 2019, 12, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 3.42 | 1.31 | 1 | ||||||

| Educational background | 2.31 | 0.74 | −0.13 | 1 | |||||

| Gender | 1.67 | 0.47 | −0.61 ** | 0.16 * | 1 | ||||

| Business tenure | 3.82 | 1.18 | 0.82 ** | −0.14 * | −0.45 ** | 1 | |||

| Social capital | 3.88 | 0.39 | 0.15 * | −0.14 | −0.10 | 0.11 | 1 | ||

| Self-efficacy | 3.92 | 0.46 | 0.06 | −0.05 | −0.10 | 0.06 | 0.30 ** | 1 | |

| Entrepreneurial orientation | 3.83 | 0.40 | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.08 | −0.03 | 0.50 ** | 0.59 ** | 1 |

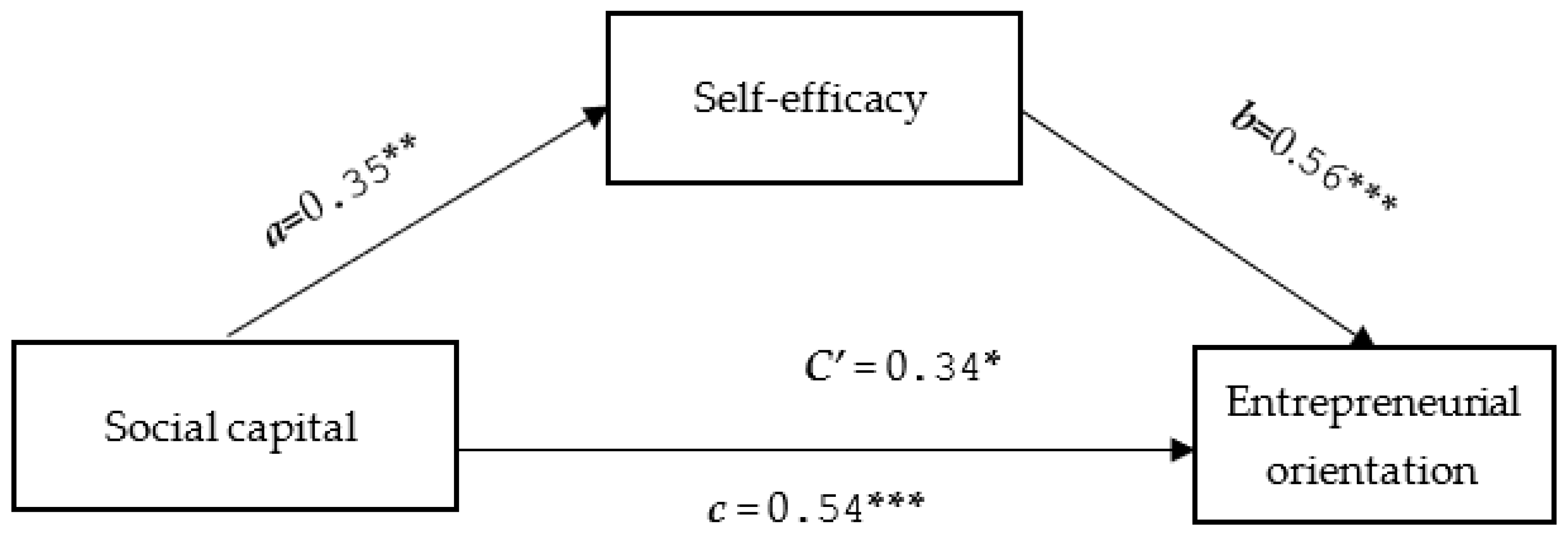

| Variable | B | SE B | β | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||||

| Constant | 1.95 *** | 0.447 | [1.07, 2.83] | |

| Social capital–entrepreneurial orientation | 0.50 *** | 0.09 | 0.39 *** | [0.32, 0.68] |

| = 0.178, F (5, 169) = 7.32, p = 0.000 | ||||

| Step 2 | ||||

| Constant | 2.74 *** | 0.43 | [1.89, 3.59] | |

| Social capital–self-efficacy | 0.35 ** | 0.08 | 0.30 ** | [0.17, 0.52] |

| = 0.09, F (5, 169) = 3.71, p = 0.032 | ||||

| Step 3 | ||||

| Constant | 0.49 | 0.42 | [−0.35, 1.33] | |

| Social capital–entrepreneurial orientation | 0.31 ** | 0.08 | 0.25 | [0.15, 0.47] |

| Social capital–self-efficacy | 0.53 *** | 0.06 | 0.49 *** | [0.39, 0.66] |

| Total (a) × (b) | 0.18 | [0.09, 0.28] | ||

| = 0.39, F (6,168) = 18.26, p = 0.000 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sulistyani, N.W.; Suhariadi, F.; Fajrianthi. Self-Efficacy as a Mediator of the Impact of Social Capital on Entrepreneurial Orientation: A Case of Dayak Ethnic Entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095620

Sulistyani NW, Suhariadi F, Fajrianthi. Self-Efficacy as a Mediator of the Impact of Social Capital on Entrepreneurial Orientation: A Case of Dayak Ethnic Entrepreneurship. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):5620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095620

Chicago/Turabian StyleSulistyani, Nuraida Wahyu, Fendy Suhariadi, and Fajrianthi. 2022. "Self-Efficacy as a Mediator of the Impact of Social Capital on Entrepreneurial Orientation: A Case of Dayak Ethnic Entrepreneurship" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 5620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095620

APA StyleSulistyani, N. W., Suhariadi, F., & Fajrianthi. (2022). Self-Efficacy as a Mediator of the Impact of Social Capital on Entrepreneurial Orientation: A Case of Dayak Ethnic Entrepreneurship. Sustainability, 14(9), 5620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095620