Tourists’ Intention of Undertaking Environmentally Responsible Behavior in National Forest Trails: A Comparative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

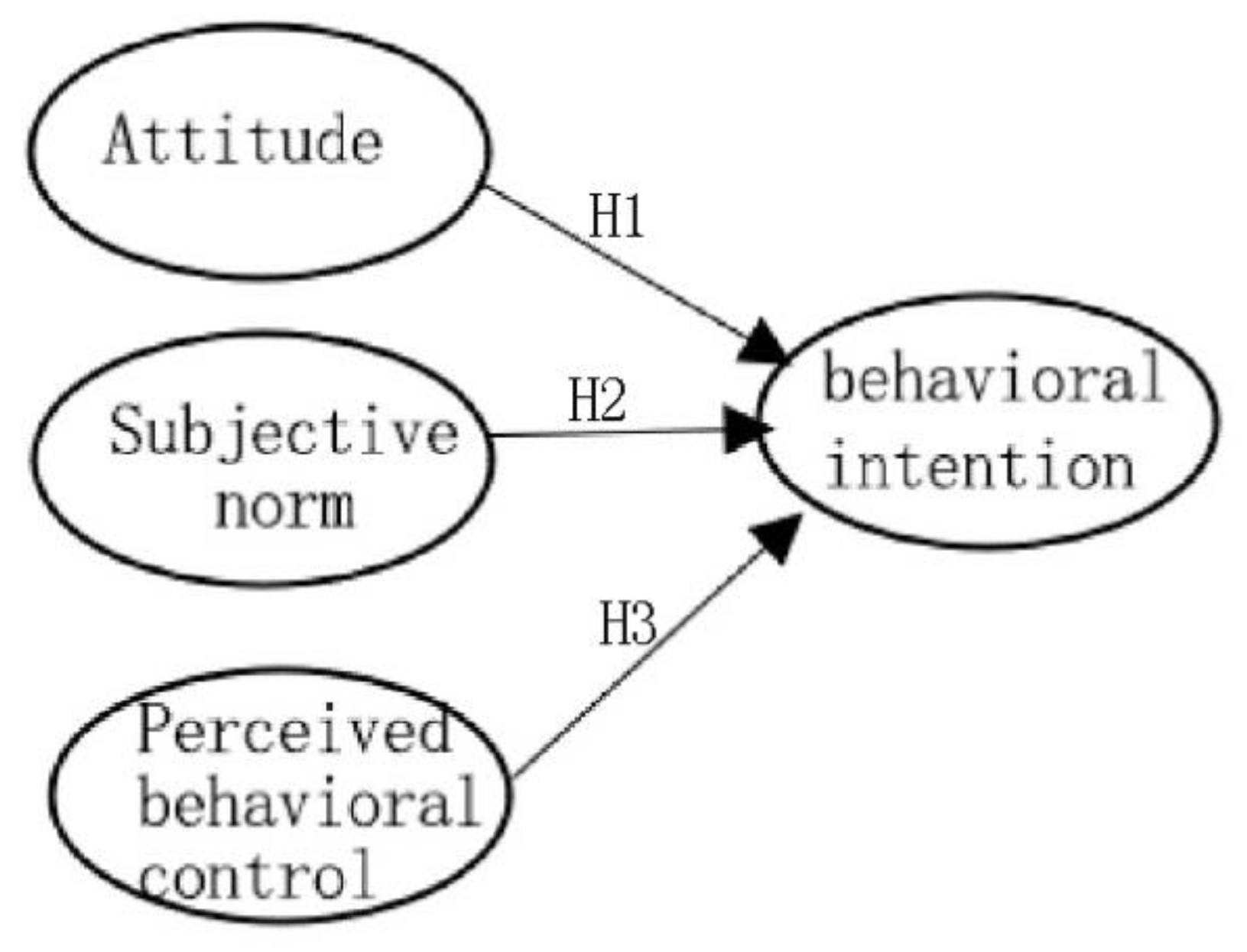

2.1. Rationality and ERB

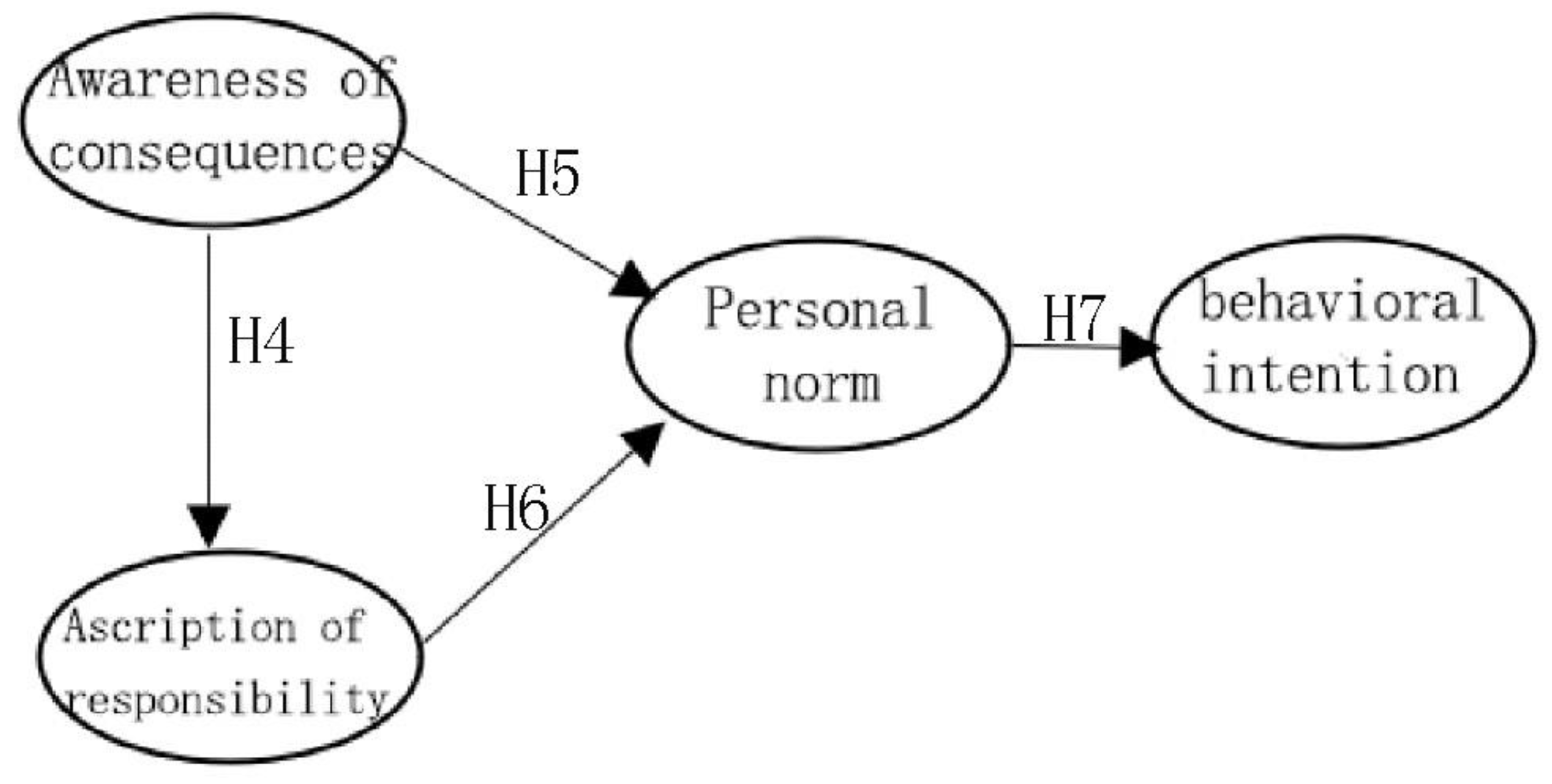

2.2. Morality and ERB

2.3. Comparison of TPB and NAM in Visitors’ ERB

3. Method

3.1. Research Sites

3.2. Instrument Measure in Survey

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sample Demographics

4.2. Reliability and Validity Test

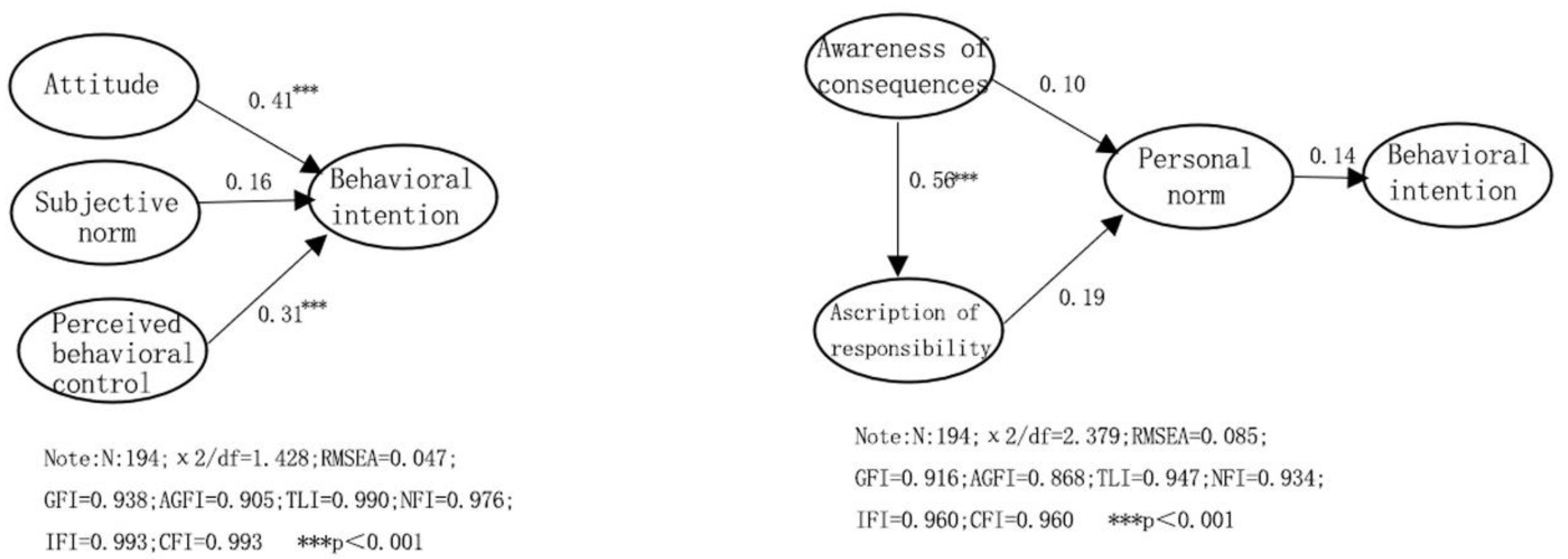

4.3. Total Sample Test on TPB and NAM Models

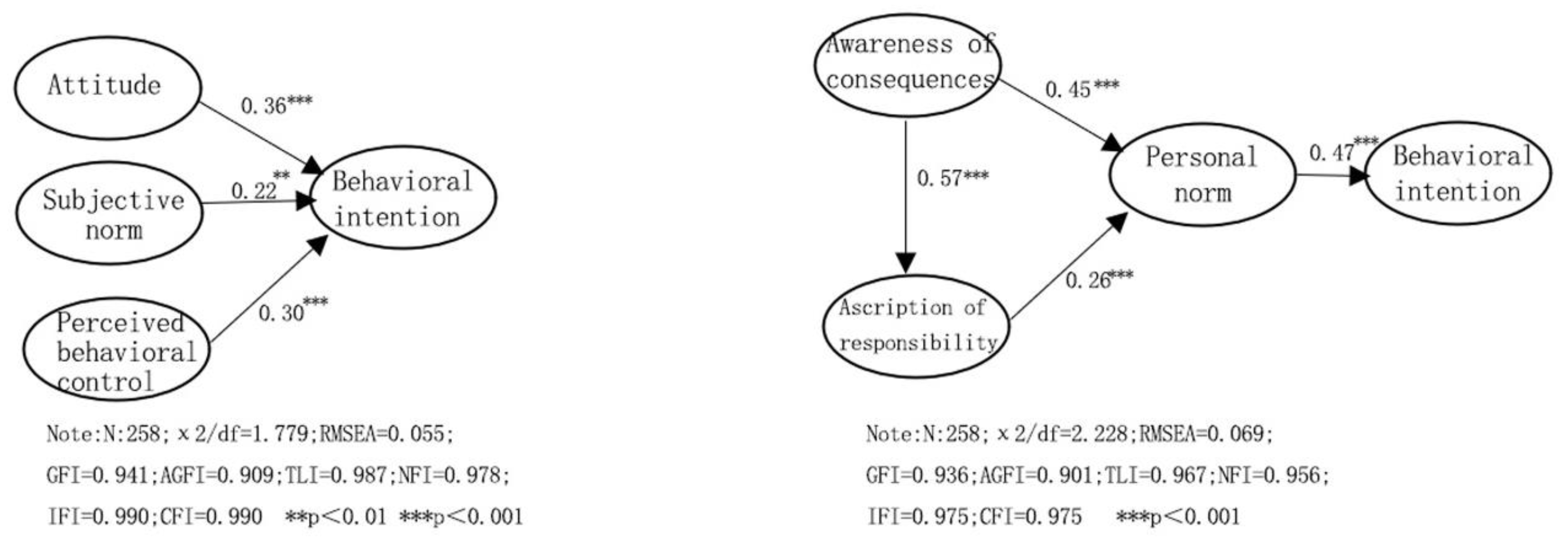

4.4. Comparison of TPB and NAM Models between Beginners and Experienced Trail Tourists

5. Conclusions

5.1. Discussion of the Results

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arbulú, I.; Lozano, J.; Rey-Maquieira, J. The challenges of municipal solid waste management systems provided by public-private partnerships in mature tourist destinations: The case of Mallorca. Waste Manag. 2016, 51, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Line, N.D.; Hanks, L.; Miao, L. Image matters: Incentivizing green tourism behavior. J. Travel. Res. 2018, 57, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Zhang, J.; Ye, Y.Y.; Wu, Q.T.; Jin, L.X.; Zhang, H.G. Residents’ Environmental Conservation Behaviors at Tourist Sites: Broadening the Norm Activation Framework by Adopting Environment Attachment. Sustainability 2016, 8, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.C.; Chao, W.X.; Alastair, M.; Morrison; Kun, Z. Fostering Resident Pro-Environmental Behavior: The Roles of Destination Image and Confucian Culture. Sustainability 2020, 12, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunkoo, R.; Seetanah, B.; Rifkha, Z.; Jaffur, K.; George, P.; Moraghen, W. Tourism and Economic Growth: A Meta-regression Analysis. J. Travel. Res. 2019, 59, 404–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Hou, Y.; Li, G. Tourists and air pollution: How and why air pollution magnifies tourists’ suspicion of service providers. J. Travel. Res. 2020, 59, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Yang, F. Do motivations contribute to local residents’ engagement in pro-environmental behaviors? Resident-destination relationship and pro-environmental climate perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 834–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evju, M.; Hagen, D.; Jokerud, M.; Olsen, S.L.; Selvaag, S.K.; Vistad, O.I. Effects of mountain biking versus hiking on trails under different environmental conditions. J Environ Manag. 2021, 278, 111554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zou, L.; Morrison, A.M.; Wu, F. Do situations influence the environmentally responsible behaviors of national park visitors? Survey from Shennongjia National Park, Hubei Province, China. Land 2021, 10, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Arora, N.; Sharma, R.; Mishra, A. Determinants of Tourists’ Site-Specific Environmentally Responsible Behavior: An Eco-Sensitive Zone Perspective. J. Travel. Res. 2021, 00472875211030328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Jeong, C. Effects of pro-environmental destination image and leisure sports mania on motivation and pro-environmental behavior of visitors to Korea’s national parks. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 10, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ji, C.; He, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L. Tourists’ waste reduction behavioral intentions at tourist destinations: An integrative research framework. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 2021, 25, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.S.; Font, X.; Liu, J. The elusive impact of pro-environmental intention on holiday on pro-environmental behaviour at home. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, I.; Ehsani, M.; Moghimehfar, F.; Aroufzad, S. Predicting Mountain Hikers’ Pro-Environmental Behavioral Intention: An Extension to the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2021, 39, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhang, J.; Chu, G.; Yang, J.; Yu, P. Factors influencing tourists’ litter management behavior in mountainous tourism areas in China. Waste Manag. 2018, 79, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, S.; Tian, Y.; Lu, L.; Eimontaite, I.; Xie, T.; Sun, Y. An exploration of hiking risk perception: Dimensions and antecedent factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019, 16, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Witte, A. “Chinese don’t walk?”–The emergence of domestic walking tourism on China’s Ancient Tea Horse Road. J. Leis. Res. 2021, 52, 424–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ge, X.; Liu, C. Hiking trails and tourism impact assessment in protected area: Jiuzhaigou Biosphere Reserve, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2005, 108, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuniyal, J.C. Solid waste management in the Himalayan trails and expedition summits. J. Sustain. Tour. 2005, 13, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.H.; Lee, M.J.; Hwang, Y.-S. Tourists’ ERB in response to climate change and tourist experiences in nature-based. Sustainability 2016, 8, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, H. Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in tourism and hospitality: A review of theories, concepts, and latest research. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1021–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Ma, Y.; Bai, K.; Li, Y.; Liu, X. Which factors influence individual pro-environmental behavior in the tourism context: Rationality, affect, or morality? Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 516–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Jin, H.Z.; Jing, J.C.; Huan, H.; Peng, Y. The influence of environmental background on tourists’ environmentally responsible behaviour. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 231, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.R.; Wang, Z.J. Study on the driving factors of tourists’ERB based on the theory of planned behavior-A case study of Beijing Bajia country park. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2018, 3, 203–207. [Google Scholar]

- Untaru, E.N.; Epuran, G.H.; Ispas, A.A. conceptual framework of consumers’pro-enviromental attitudes and behaviours in the tourism context. Econ. Sci. 2014, 7, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Beauchamp, M.R.; Conner, M.; Bruijn, G.J.D.; Kaushal, N.; Latimer, C.A. Prediction of depot-based specialty recycling behavior using an extended theory of planned behavior. Environ. Behav. 2015, 47, 1001–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.; Sheu, C. Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Drivers of customer decision to visit an environmentally responsible museum: Merging the theory of planned behavior and norm activation theory. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Maki, A.; Chen, C.; Dong, B.; Day, J.K. Investigating willingness to save energy and communication about energy use in the American workplace with the attitude-behavior-context model. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 32, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jin, C.; Ge, X.; Wang, Y. Study of influencing factors of household waste reduction behaviors in Beijing. Int. J. Appl. Environ. Sci. 2013, 8, 615–624. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.J.; Jin, H.R.; Lou, C.W. Norm Activation Model:An Effeective Theoretical Model for Predicting Citizens’ Pro-environmental Behaviors. J. Northeast. Nat. 2016, 18, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.S.; Myong, J.; JinSoo, H. Cruise travelers’ environmentally responsible decision-making: An integrative framework of goal-directed behavior and norm activation process. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 56, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G.; Bartels, J. The norm activation model: An exploration of the functions of anticipated pride and guilt in pro-environmental behaviour. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013, 39, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, H.C.; Hsieh, C.-M.; Ramkissoon, H. Face consciousness, personal norms, and environmentally responsible behavior of Chinese tourists: Evidence from a lake tourism site. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 50, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Luzon, M.D.C.; Calvo-Salguero, A.; Salinas, J.M. Comparative study between the theory of planned behavior and the valueebeliefenorm model regarding the environment, on Spanish housewives’ recycling behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 2797–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.S. Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Hunecke, M.; Blobaum, A. Social context, personal norms and the use of public transportation: Two field studies. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Action-Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhl, J., Beckman, J., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg/Berlin, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhan, W. How to activate moral norm to adopt electric vehicles in China? An empirical study based on extended norm activation theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3546–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Font, X.; Jing, Y.L. Tourists’ Pro-environmental Behaviors:Moral Obligation or Disengagement? J. Travel. Res. 2020, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ping, L.; Zhou, B.; Chris, R. Hiking in China: A fuzzy model of satisfaction. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 22, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.; Hanim, N.; Azmi, M. Satisfaction in Tourism Operations. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Change 2019, 8, 18–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, C.A.; Harbor, L.C. Pro-environmental tourism: Lessons from adventure, wellness and eco-tourism (AWE) in Costa Rica. J. Outdoor. Rec. Tour. 2019, 7, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A.; Manthiou, A.; Chiang, L.; Tang, L.R. An assessment of value dimensions in hiking tourism: Pathways toward quality of life. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 20, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhama, B. The meta-analysis of ecotourism in National Parks. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2020, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Torbidoni, E.I.F. Managing for recreational experience opportunities: The case of hikers in protected areas in Catalonia, Spain. Environ. Manag. 2011, 47, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Kreiner, N.; Kliot, N. Why do people hike? Hiking the Israel National Trail. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2017, 108, 669–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.L.; Tsung, H.L. How do recreation experiences affect visitors’ ERB? Evidence from recreationists visiting ancient trails in Taiwan. J. Sustain. Tour 2020, 28, 705–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, H.; Jin, H.Z.; Chang, W.; Peng, Y.; Guang, C. What influences tourists’ intention to participate in the Zero Litter Initiative in mountainous tourism areas: A case study of Huangshan National Park, China. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 657, 1127–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen; Driver. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Leisure Choice. J. Leisure Res. 1992, 24, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. Developing an extended theory of planned behavior model to predict consumers’ intention to visit green hotels. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonglet, M.; Phillips, P.S.; Bates, M.P. Determining the drivers for householder pro-environmental behavior: Waste minimization compared to recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 2004, 42, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.C.; Huang, S. An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior Model for Tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2010, 36, 390–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.J.; Geng, G.J. Ping Sun Determinants and implications of citizens’ environmental complaint in China: Integrating theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behavior: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Fan, J.; Zhao, D. Predicting Household PM2.5-Reduction Behavior in Chinese Urban Areas: An Integrative Model of Theory of Planned Behavior and Norm Activation Theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 145, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.-P.; Chan, H.-W. Generalized trust narrows the gap between environmental concern and pro-environmental behavior: Multilevel evidence. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 48, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Knezevic Cvelbar, L.; Grün, B. A sharing-based approach to enticing tourists to behave more environmentally friendly. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Judith, I.M.; De, G.; Linda, S. Morality and Prosocial Behavior: The Role of Awareness, Responsibility, and Norms in the Norm Activation Model. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 149, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J.; Lee, M.J.; Kim, J. Word-of-mouth, buying, and sacrifice intentions for eco-cruises: Exploring the function of norm activation and value-attitude behavior. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Yu, A. The role of perceived effectiveness of policy measures in predicting recycling behaviour in Hong Kong. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 2014, 83, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory of Moral Thought and Action. In Handbook of Moral Behavior and Development; Kurtines, W.M., Gewirtz, J.L., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 45–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory in Cultural Context. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 51, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Leisch, F. An Investigation of Tourists’ Patterns of Obligation to Protect the Environment. J. Travel Res. 2008, 46, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.C.; Wu, M.Y. Rationality or Morality? A Comparative Study of Pro-environmental Intention of Local and Nonlocal Visitors in Nature-Based Destinations. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 11, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, N. Willingness to Pay for Carbon Reduction Against Climate Change: A Social Survey in Beijing, China. Int. J. Sci. Res. Multidiscip. Stud. 2020, 6, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, G. Antecedents of employee electricity saving behavior in organizations: An empirical study based on norm activation model. Energ. Policy 2013, 62, 1120–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, V.D.W.; Steg, L. One model to predict them all: Predicting energy behaviours with the norm activation model. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenberg, I.; Blöbaum, A.; Matthies, E. Environmental motivations for energy use in PV households: Proposal of a modified norm activation model for the specific context of PV households. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 55, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Ranney, M.; Hartig, T.; Bowler, P.A. Ecological behaviour, environmental attitude, and feelings of responsibility for the environment. Eur. Psychol. 1999, 4, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sparks, P.; Shepherd, R. The role of moral judgments within expectancy-value based attitude-behavior models. Ethics Behav. 2002, 12, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellette, J.A.; Wood, W. Habit and intention in everyday life: The multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knussen, C.; Yule, F.; MacKenzie, J.; Wells, M. An analysis of intentions to recycle household waste: The roles of past behaviour, perceived habit, and perceived lack of facilities. J. Environ. Sci. 2004, 24, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. College youth travelers’ eco-purchase behavior and recycling activity while traveling: An examination of gender difference. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 740–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalot, F.; Quiamzade, A.; Falomir-Pichastor, J.M.; Gollwitzer, P.M. When does self-identity predict intention to act green? A self-completion account relying on past behaviour and majority-minority support for pro-environmental values. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 61, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzad, F.; Nanthini, A.; Mohammad, I.; Kavigtha, M.K.; Ming-Lang, T.; Nelson, L. Determinants of hotel guests’ pro-environmental behaviour: Past behaviour as moderator. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 102, 103167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, G.D.; Leo, M.D. Repeated behavior and environmental psychology: The role of personal involvement and habit formation in explaining water consumption. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 33, 1261–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untaru, E.N.; Ispas, A.; Candrea, A.N.; Luca, M.; Epuran, G. Predictors of individuals’ intention to conserve water in a lodging context: The application of an extended theory of reasoned action. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 59, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutcher, D.D.; Finley, J.C.; Luloff, A.E.; Johnson, J.B. Connectivity With Nature as a Measure of Environmental Values. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 474–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, E.; Williams, K.J.H. Connectedness to nature, place attachment and conservation behavior: Testing connectedness theory among farmers. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J.; Lee, S. Cognitive, affective, normative, and moral triggers of sustainable intentions among convention-goers. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, K.; Teng, F.; Chow, J.T.; Chen, Z. Desiring to connect to nature: The effect of ostracism on ecological behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M.P. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schultz, P.W. The structure of environmental concern: Concern for self, other people, and the biosphere. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, M.; Vonderembse, M.A.; Lim, J.S. Manufacturing technology and strategy formulation: Keys to enhancing competitiveness and improving performance. J. Oper. Manag. 1999, 17, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Wu, M. Tourists’ pro-environmental behaviour in travel destinations: Benchmarking the power of social interaction and individual attitude. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1371–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J.; Benjamin, S.; Leonard, H. Recycling on vacation: Does pro-environmental behavior change when consumers travel? J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2019, 29, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Wei, W. Consumers’ pro-environmental behavior and its determinants in the lodging segment. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2016, 40, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cui, F.; Wu, S.S.; Wu, W.Z. Analysis of the factors impacting on air travelers’ willingness to pay for carbon offsets: Based on theory of planned behavior and theory of norm-activation. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2017, 11, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Wong, N.; Abe, S.; Bergami, M. Cultural and situational contingencies and the theory of reasoned action: Application to fast food restaurant consumption. J. Consum. Psychol. 2000, 9, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapinski, M.K.; Rimal, R.N. An Explication of Social Norms. Commun. Theor. 2005, 15, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, R.N.; Real, K. How Behaviors are Influenced by Perceived Norms. Commun. Res. 2005, 32, 389–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder, D.A. Some determinants of the persuasive power of in-groups and out-groups: Organization of information and attributions of independence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 1202–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Mosquera, N.; García, T.; Barrena, R. An extension of the theory of planned behavior to predict willingness to pay for the conservation of an urban park. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 135, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ha, S. Understanding consumer recycling behavior: Combining the theory of planned behavior and the norm activation model. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2014, 42, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs and Variable Items | Factor Loading | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude (ATT) Participating in ERB in national forest hiking trails is wise (ATT1) | 0.782 | 0.962 | 0.873 |

| Participating in ERB in national forest hiking trails is good (ATT2) | 0.786 | ||

| Participating in ERB in national forest hiking trails is worthwhile (ATT3) | 0.807 | ||

| Participating in ERB in national forest hiking trails is beneficial (ATT4) | 0.804 | ||

| Subjective norm (SN) My friend’s support for my ERB (SN1) | 0.819 | 0.945 | 0.829 |

| People who are important to me think I should participate in ERB (SN2) | 0.802 | ||

| People who are important to me would want me to participate in ERB (SN3) | 0.734 | ||

| Perceived behavioral control (PBC) I have enough physical strength to participate in protecting the environment (PBC1) | 0.819 | 0.968 | 0.869 |

| I am confident that I can do something helpful to protect the environment (PBC2) | 0.833 | ||

| I have sufficient time to participate in protecting the environment (PBC3) | 0.839 | ||

| Awareness of consequences (AC) Trail tourists’ activities have negative impacts on natural environment (AC1) | 0.812 | 0.916 | 0.870 |

| Trail tourists’ activities have negative impacts on wild animals and plants (AC2) | 0.815 | ||

| Trail tourists’ activities lead to water pollution (AC3) | 0.865 | ||

| Ascription of responsibility (AR) I believe that every trail tourist is partially responsible for environmental problems in this trail (AR1) | 0.835 | 0.867 | 0.869 |

| I feel that all trail tourists are jointly responsible for environmental problems in this trail (AR2) | 0.869 | ||

| Every trail tourist must take responsibility for environmental problems in this trail (AR3) | 0.783 | ||

| Personal norm (PN) I feel guilty for not doing ERB (PN1) | 0.771 | 0.874 | 0.857 |

| I think ERB is a moral obligation (PN2) | 0.853 | ||

| ERB is part of my ethics (PN3) | 0.824 | ||

| Behavioral intention (BI) I am willing to participate in ERB (BI1) | 0.764 | 0.952 | 0.783 |

| I plan to participate in ERB (BI2) | 0.736 | ||

| I am willing to ask my relatives and friends to participate in ERB (BI3) | 0.716 |

| TPB Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | NAM Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | 0.795 | AC | 0.831 | ||||||

| SN | 0.704 ** | 0.786 | AR | 0.481 ** | 0.829 | ||||

| PBC | 0.645 ** | 0.697 ** | 0.831 | PN | 0.521 ** | 0.428 ** | 0.816 | ||

| BI | 0.695 ** | 0.667 ** | 0.664 ** | 0.739 | BI | 0.393 ** | 0.361 ** | 0.383 ** | 0.739 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Q.; Popa, A.; Sun, H.; Guo, W.; Meng, F. Tourists’ Intention of Undertaking Environmentally Responsible Behavior in National Forest Trails: A Comparative Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095542

Zhang Q, Popa A, Sun H, Guo W, Meng F. Tourists’ Intention of Undertaking Environmentally Responsible Behavior in National Forest Trails: A Comparative Study. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):5542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095542

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Qing, Arporn Popa, Huazhen Sun, Weifeng Guo, and Fang Meng. 2022. "Tourists’ Intention of Undertaking Environmentally Responsible Behavior in National Forest Trails: A Comparative Study" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 5542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095542

APA StyleZhang, Q., Popa, A., Sun, H., Guo, W., & Meng, F. (2022). Tourists’ Intention of Undertaking Environmentally Responsible Behavior in National Forest Trails: A Comparative Study. Sustainability, 14(9), 5542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095542