Abstract

Multi-stakeholder (e.g., governments, residents, the “3C” of community and “third party”) co-governance has become a hot topic in the community-renewal research field. However, the co-ordination of various rights and interests hinders the co-governance of multiple stakeholders, particularly in China. Current research on the mechanisms of multiple co-governance remains inadequate. This article presents a typical case of multi-stakeholder co-governance for community renewal with respect to adding elevators to an apartment building in Shanghai’s inner city. The multi-stakeholder co-governance process involved in this research differs from the traditional model, which is mainly led by governments. Field investigations and in-depth interviews were employed to explore how multiple stakeholders conduct dialogues and negotiations in the process of elevator installation. We summarize the key elements of community renewal, show the internal mechanism, and provide a new practical and methodological investigation of multi-stakeholder co-governance. This article highlights the significance of a good interest-co-ordination mechanism and simplification of the community-renewal process. It is also suggested to encourage the participation of multiple stakeholders and to promote co-operation between the community and enterprises in community governance.

1. Introduction

Urban renewal is a continuing, important issue worldwide that can alleviate urban decay and improve land value and the environment [1,2,3,4,5]. As the basic unit of a city, the community is the main living space for human beings, and community construction has become an important module of urban renewal [6,7,8,9]. Community renewal first emerged in developed countries [10]. In the 1930s, in response to the decay of central urban areas caused by excessive suburbanization, government-led community renewal characterized by large-scale demolition and reconstruction began to appear in the UK and France, resulting in serious social problems and damage to residents’ interests [11]. With the influence of humanism and sustainable development, progressive small-scale renewal with multiple-stakeholder participation has been widely accepted, and community-based planning has gradually developed into the main method of renewal [12,13,14,15]. Different countries have introduced different policies and guidelines, such as the UK’s “LSPS” (Local Strategic Partnerships) program and “Active Citizens” [16,17,18], the establishment of community enterprises in the Netherlands [19], and the “Urban Development Policy Act” (Loi d’Orientation de la Ville: LOV) of France [20], to promote multiple-stakeholder participation and co-operation. The US government has continuously strengthened the tripartite co-operation of the government, private sectors, and citizens, by promoting public-private partnerships (PPPs), evolving community-development corporations (CDCs), and other non-profits, to encourage community activism and engagement [21]. These strategies and methods provide a reference for community renewal in China.

Community renewal has also become an important strategic and prominent issue in China and other developing countries [22,23,24,25]. Compared with developed countries, community renewal in China was carried out later and has mainly focused on the physical restoration of old houses [26]. Problems are widespread in old communities, such as the degradation of building performance, lack of public supporting facilities, obviously backward living standards, and non-standard safety management, which have seriously affected the living safety and quality of community residents, especially with regard to aging [27,28]. According to statistics, 170,000 old urban communities needed to be renovated in China by the end of May 2019, involving hundreds of millions of residents, and 39,700 old residential areas were renovated in 2020, benefiting more than 7 million households [29,30]. China has carried out a series of programs, such as “Ecological Restoration”, “Urban Rehabilitation”, “Beautiful Home”, and “Beautiful Block”, to promote community renewal [31,32,33]. On this basis, Shanghai has also successively launched the “Walking Shanghai 2016—Community Space Micro-Renewal Plan” and issued the Shanghai Urban Master Plan (2017–2035) and Shanghai Urban Renewal White Paper (2019) to explore a community-renewal model with the broad participation of the government, residents, planners, artists, and other stakeholders.

However, owing to the complexity of old communities and the diversification of stakeholders, there are various challenges and difficulties in community renewal and governance [34]. The projects of China’s community renewal and governance are always led by the government because of China’s authoritarian system [35,36], especially in Shanghai [37]. The principal status of residents is emphasized in community planning and governance [38]; but in practice, it is difficult to carry this out as a result of the government-led model [39]. In fact, community renewal and co-governance are complex; therefore, it is also necessary to clarify the relationships among multiple stakeholders and analyze how they interact, negotiate, and form collective actions in the process of community governance.

With the aggravation of aging, the renewal of communities suitable for aging has become an urgent issue. Most old communities do not have elevators, which is inconvenient for the elderly. As one of the projects for the aging in community renewal, elevator installation has received increasing attention from the government and residents. However, the co-ordination involved in elevator installation is more complex, and it is difficult to implement. As Yuanlong Apartment is the first community in Shanghai to successfully install elevators [40], its experience can serve as a reference for other areas.

This study contributes to the literature in two ways. As a global metropolis, Shanghai has rich experience in community renewal and governance and is often regarded as a model of modernization. Therefore, based on the case of installing elevators in an apartment in Shanghai’s inner city, this article analyzes the process of multi-stakeholder co-governance and reveals the internal mechanism of multi-stakeholder interaction, which adds the Chinese approach to the community-renewal theory of multi-stakeholder co-governance. In addition, this study provides new experiences for community governance, highlighting current problems and future paths. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Following the introduction, Section 2 is a literature review, Section 3 presents the methodology, Section 4 is a case analysis of multi-stakeholder co-governance, Section 5 discusses the results and Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

In 1995, the Commission on Global Governance (CGG) defined “Governance is the sum of many ways in which individuals and institutions, whether public or private, manage their common affairs. It is a continuous process of reconciling conflicting or different interests and taking co-operative actions” [41]. This indicates the importance of co-operation between multiple stakeholders. Stoker proposed that “Governance refers to a set of institutions and actors that are drawn from but beyond government” [42], which also emphasized the momentous role of other subjects in the process of governance. In contrast to the previous government’s dominant management, governance emphasizes self-organization and resource exchange, competition, and co-operation among multiple stakeholders [43,44]. Many scholars have captured and recognized multi-stakeholder co-governance.

Community renewal involves multiple stakeholders and is a complicated process that has attracted the attention of many scholars [45,46,47,48,49]. Co-governance is becoming increasingly popular, emphasizing the participation of multiple stakeholders in addressing public affairs [50,51,52,53]. Multi-stakeholder co-governance is mainly derived from poly-centric governance theory, which points out the multi-directional co-ordination relationship of trust and co-operation between government, society, and citizens [54,55]. In social governance, multiple stakeholders are equal and jointly handle public affairs [56,57]. The government should be a resource provider, not an executor [10]. For stakeholders, the generally accepted definition is “any group or individual who can affect, or is affected by, the achievement of the organization’s objectives” [58,59,60]. Based on this, the stakeholders of community renewal are defined as groups or individuals who may affect the realization of project objectives in the process of community renewal, including residents, neighborhood committee, owner committees, property management companies, enterprises, construction teams, and the media. The opinions of these stakeholders influence the decision-making processes, and their interests are also affected.

Community governance requires a combination of top-down and bottom-up approaches [61]. The top-down government-led model has caused many social problems [62]. In most renewal projects, because of the neglect of residents’ subjectivity in governance, residents only indirectly participate in the planning survey or consultation of the project, and lack the opportunity to directly participate in the design or decision-making process. As a result, residents’ rights in the negotiation of benefit distribution are weakened [63,64], which leads to the disapproval and even opposition of stakeholders, giving rise to social injustice and inequality [65]. Governance requires the extensive participation and co-ordination of stakeholders [66,67]. Co-ordinating the conflicts of interests between multiple stakeholders with game theory and other methods, and building a reasonable stakeholder participation mechanism, will maximize the effectiveness of governance [64,68,69]. Establishing urban partnerships among multiple stakeholders, including local governments, enterprises, voluntary organizations, and community groups, is a good way to implement renewal plans in developed countries [70,71]. In China, city alliances and co-operation mechanisms have mostly been established and the government’s influence is much stronger [47,50]. Encouraging and actively listening to public opinion by the government will increase the willingness of different stakeholders [31,72].

Community renewal involves several issues and multiple stakeholders [73]. Conflicts of interest and complex relationships between multiple stakeholders hinder co-governance [34,74,75]. Awareness of civic participation in developing countries is low [76]. Leaders with a certain ability are often required to handle community public affairs [77,78,79,80]. Therefore, it is necessary to rethink the “public interest” and carry out relevant education and publicity to improve the skills and willingness of different stakeholders [60,81]. In addition, multi-stakeholder co-governance of communities in China is still in its infancy [82]. It is important to investigate the complex interactions among multiple stakeholders in the community renewal process.

3. Methodology

A qualitative method was employed in this study, which can be divided into the following parts. First, a field investigation was conducted by participating in a media activity named “City Walks”. The investigators were organized to follow the media into the community to learn about the specific process of installation of elevators in Yuanlong Apartment. Second, in-depth interviews with community residents, neighborhood-committee cadres, and employees of the elevator company were conducted, to obtain the actual process of installing elevators and various obstacles encountered from different stakeholders’ perspectives. Third, we then analyzed the role played by each stakeholder in the whole process of the elevator installation and their interactions according to the data collected. Finally, we integrated all data and preliminary analysis results and conducted a comprehensive study.

Specifically, based on the relevant materials obtained from field research, we chose the interviewees related to the case of community governance (Table A1), designed the corresponding interview outline (Table A2), conducted in-depth interviews according to the interview outline with their consent, and obtained written records of the interviews. Regarding the interviews, one with each candidate lasted approximately 20–30 min. The authors conducted a total number of 13 in-depth interviews in 2019 and 2021. Regarding the selection of interviewees, this study adhered to two principles. The first is to involve as many subjects of community governance as possible, including neighborhood-committee cadres, residents, and heads of elevator companies. The second is to select the residents participating directly and indirectly in community governance, because not all community members participated in community governance. Through sorting out interview records, some important interview contents are quoted in the paper, and some are integrated into the conclusion and discussion of the paper. All data acquisition was explained to the interviewees in advance with their consent and was indicated to be for scientific-research needs.

4. Case Analysis: Elevator Installation under Multi-Stakeholder Co-Governance

4.1. Background

Home-based care facilities in the community are of great concern in the community renewal of Shanghai. At the end of 2018, there were more than five million people aged over 60 years in the household registration system of Shanghai, and the degree of aging exceeded 34% [83]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to construct facilities for the aging in the community. The installation of elevators in existing multi-story residences has received increasing attention from governments and residents. Approximately 429 communities in Shanghai have completed the project of installing elevators through consultation with residents, of which 137 have been completed and put into operation (including 19 complete sets of renewal) and 73 are under construction [84]. As the first community to successfully install all five elevators in Shanghai, Yuanlong Apartment underwent multi-stakeholder consultation and formed a collective action throughout the entire process, which embodied the idea of co-governance by multiple stakeholders. This is a typical case of community renewal and is of great significance.

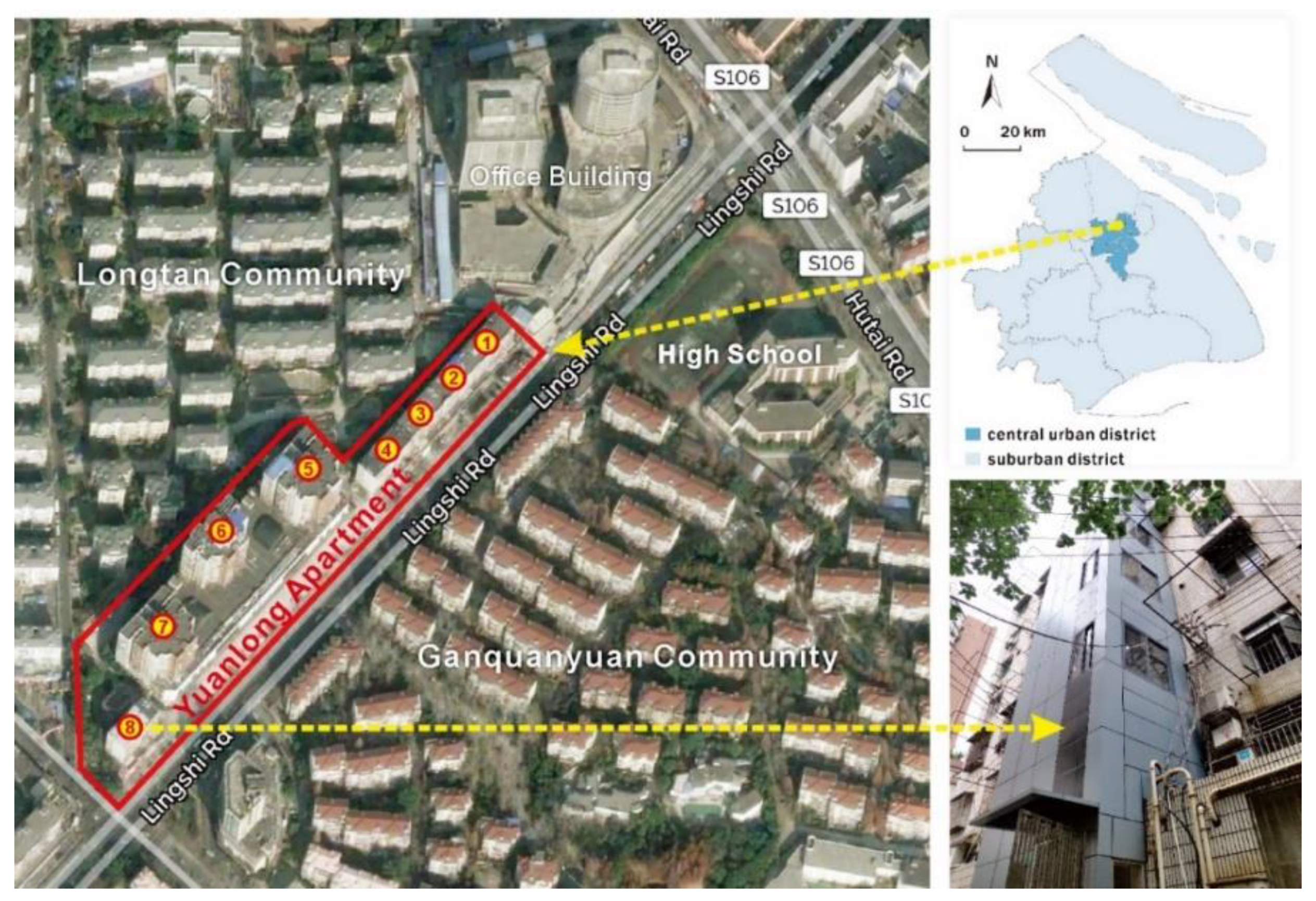

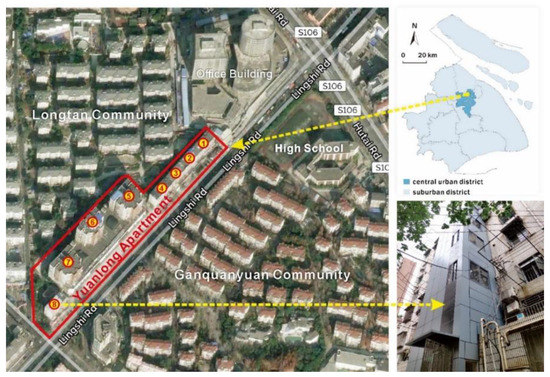

Yuanlong Apartment is in Pengpu Town, Jing’an District, in the inner city of Shanghai (Figure 1). The Jing’an District government launched the “Beautiful Home” plan in 2015 and the “Beautiful Block” plan in 2016, aiming to propel community self-governance and co-governance. As an old community built in 1997, Yuanlong covers a relatively small area (approximately 0.01 km2), with three high-rise residences (Buildings 5, 6, and 7) and five multi-story residences (Buildings 1, 2, 3, 4, and 8). There are 324 households in Yuanlong, including the majority of the local population and a few immigrants. Among them, there are 120 households in the five multi-story residences, about 70% of whom are over 60 years old, and eight of whom are over 80 years old. The lack of elevators in the five multi-story residences causes inconvenience to many elderly people, so it is a matter of great urgency to install elevators to promote community renewal.

Figure 1.

Location of Yuanlong Apartment in Shanghai.

4.2. Case Analysis of Multi-Stakeholder Co-Governance

Yuanlong Apartment planned to install the elevators in 2014. A real-estate developer in Shanghai proposed to use the “6 + 1” model to install elevators for the five multi-story residences of Yuanlong [40]. The “6 + 1” model is to add a floor to the original residential roof, and the proceeds from the sale of this floor would then be used to subsidize the costs of elevator installation and maintenance. Owing to the high housing prices in Shanghai, developers can recover costs in a short period of time, and residents can obtain an elevator conveniently without paying. Therefore, all the residents of the community signed an agreement. However, at that time, the government regarded elevator installation as a real-estate development project. The “6 + 1” model conflicted with relevant laws and regulations and in the end was not approved by the government. In 2016, the Shanghai government stepped up the pilot project and specified the procedures for installing elevators in multi-story residences. Residents of Yuanlong started to organize the elevator installation spontaneously.

4.2.1. Independent Negotiation of Residents

According to the “Notice on Approval of Construction and Management of Elevators in Existing Multistory Residences in Shanghai” ([2016] No. 833), adding elevators to existing multi-story residences should be the responsibility of the owners’ committee of the residential district to which the residence belongs [85]. However, owing to different ideas and complex interest-co-ordination issues and with no precedent for installing elevators, the owners’ committee of Yuanlong did not support or object to the project and proposed that residents organize it themselves. Therefore, led by community party members and group leaders of each building, some residents of Yuanlong spontaneously set up a joint elevator-construction group to represent all residents of the community in charge of consultation and co-ordination regarding elevator installation. A member of the joint construction group (YW5) explained as follows:

“The owners’ committee is the main body to apply for the elevator installation, but they refused, so we signed an agreement with them, that is, they are exempt from liability and only responsible for stamping, and the relevant legal responsibility and economic responsibility is our own.”

Elevator installation must first obtain the consent of community owners, which is key to obtaining government approval. According to regulations, the installation of elevators requires the consent of more than two-thirds of the owners in the property-management area and more than 90% of the owners of this building at the same time. As stipulated in the notice, as long as one owner objects to installing an elevator, the elevator cannot be installed. The members of the joint construction group (YW5) stated:

“At the first consultation, the compliance rate (consensual rate) of every building was 97% or 98%, and only one or two households in every building disagreed. However, when we later submitted the relevant materials to the district housing office after we reached an agreement rate of over 90% for every building, the staff said that there was still another regulation at the end of the document, that is, the remaining 10% of residents could not have strong objections” [40].

Residents’ opposition mainly focused on two aspects. The first was worries about the negative impact of installing elevators. Adding elevators involves the reconstruction of existing residences, which affects the safety of houses, impacts the ventilation and lighting of low-rise residents, and produces noise [40]. In addition, adding elevators will bring about changes in a house’s market value. Generally, after the installation of elevators, the market value of low-rise houses in buildings decreases, while the value of high-rise houses increases. Therefore, some low-rise residents did not agree to installing an elevator [40].

Second, there was no urgent need. Installing elevators mainly provides convenience for the elderly and residents in wheelchairs, while younger people, low-rise residents, and some owners who rented out the houses had no urgent need for the elevator, so they usually did not agree to install elevators. A resident of Yuanlong (YM10) said:

“At that time, we needed to obtain the consent of more than 90% of each building to install the elevator. There were 20 households in one building, and if two households disagreed, the elevator could not be installed. As long as one household doesn’t agree, we need to communicate and negotiate. It doesn’t matter if the household doesn’t want to pay for the installation as long as they sign up to let us install it. There was a situation where two families in a building refuse to pay for the installation, but that is not the same as not agreeing to install an elevator, and if they don’t agree with installing it, we can’t install it at all.”

In response to these objections, the members of the joint construction group carried out multi-faceted and comprehensive ideological persuasion and even invited specialized technicians and elevator-company staff to answer questions face-to-face for residents. At the invitation of residents, the elevator company, selected by Yuanlong, held consultation and briefing sessions, analyzed various pros and cons for residents, and allowed residents to experience a model elevator to dispel their doubts and obtain their trust. Finally, more than 90% of the owners in every building and 87% of the owners in the community agreed to install the elevators. The remaining residents chose to abstain. A consensus on the installation of elevators was thus reached in Yuanlong.

In addition, community residents needed to agree on the design scheme of elevator installation and the apportionment of related expenses (including installation, operation, cleaning, maintenance, and repair). The members of the joint construction group visited and inspected different elevator companies and finally decided to purchase the one-stop elevator service of an elevator company through a vote of all the owners who wanted to install elevators. The total contract cost for each elevator was CNY 610,000. After excluding government subsidies, the actual cost to residents was CNY 370,000, which was required to be apportioned among the owners of every building.

Residents also had different opinions on the apportionment of expenses. A resident of Yuanlong, who is also a neighborhood-committee cadre and a member of the joint construction group (YW2), said:

“The expenses of elevator in every building are apportioned to every floor in proportion, and then is equally apportioned to the households on each floor. However, there are four households of small size and another four of large size on the sixth floor of the five multistory residential buildings in Yuanlong, which makes some residents of small units think the scheme is unfair and opposed to it. However, the elevators are used by people, and it is also unfair to apportion expenses according to the area of the house.”

In addition, some residents did not oppose elevator installation but objected to paying for elevator installation. Through consultations with residents, a consensus was reached on expenses: The first and second floors do not need to pay. Starting from the third floor, the expense apportionment ratio was 3.02% per household, and each floor increased by 1.1 percentage points per household. Sixth-floor residents pay the highest expense ratio of 6.32% per household (Table 1). As the elevator company provided free maintenance for five years, the apportionment of related expenses (including operating, cleaning, maintenance, and repair) after the elevator installation was allocated according to the following method: The electricity cost of the elevator was apportioned by the residents of the second to sixth floors of every building. Starting from the second floor, the expense apportionment ratio was 3% per household, and each floor was increased by 0.5 percentage points per household. The cleaning, maintenance, and repair costs of elevators were apportioned equally by the owners of the elevators (Table 2). Owing to the different situations of every building, the residents would co-ordinate and adjust the proportion of elevator-related expenses according to specific situations. A group leader in community building (YM4) explained the following:

Table 1.

Cost-sharing scheme to add an elevator in Yuanlong Apartment.

Table 2.

Running-cost-sharing scheme of elevator in Yuanlong Apartment.

“Some residents are unwilling to pay, which would be apportioned equally by the remaining households on the same floor. If they want to take the elevator again, they need to pay for the expenses first.”

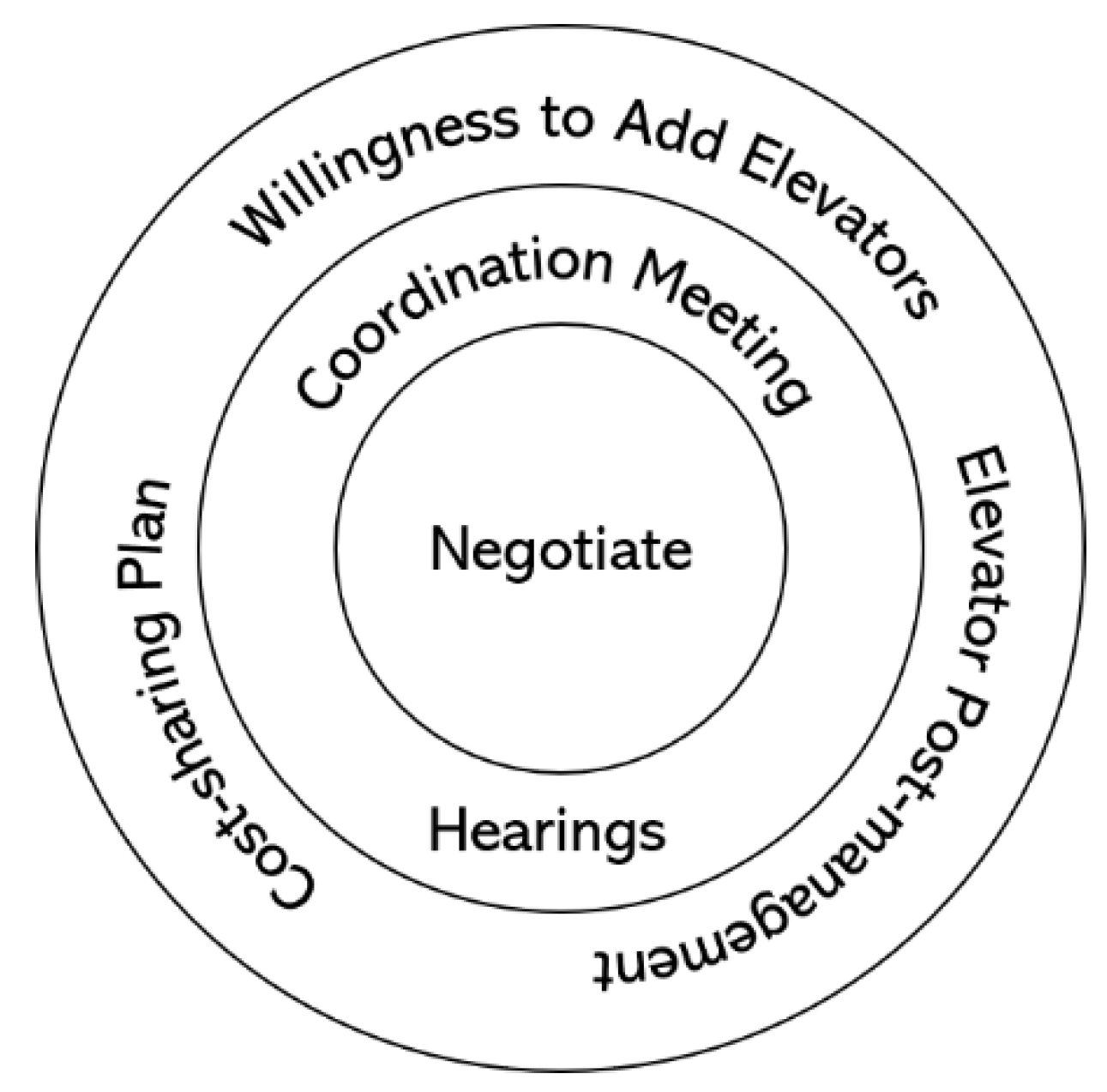

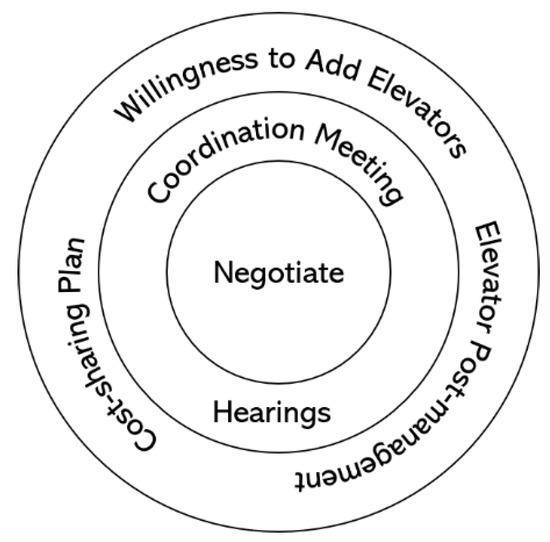

Residents’ consultations and autonomy were indispensable to the success of installing elevators (Figure 2). When the owners’ committee did not take the initiative in the installation of the elevator, the residents spontaneously set up a joint elevator-construction group to shoulder the responsibility of public affairs, which effectively prevented the decentralization of responsibility. Faced with issues such as seeking the owners’ consent, fee payments, and elevator management, on the basis of fully accepting different opinions and suggestions, residents sought the help of professionals, and held consultation meetings and hearings to resolve confusion and doubts. Information transparency, openness, and positive external guidance ensured democracy. At the same time, the residents also conducted independent negotiations and consultations. In the process of discussion and communication, contradictions were gradually resolved, consensus was reached, and the content of the agreement was gradually improved and refined. All of these effectively resolved the differences among residents and effectively protected their interests.

Figure 2.

Residents’ independent negotiation.

4.2.2. From “Lead” to “Guide” by Government

In the community-renewal project, the government is constantly changing its role from the previous “lead” to the current “guide,” to support community renewal in all aspects. This also reflects the government’s shift from management to governance. Based on the “Beautiful Home” and “Beautiful Block” plans, the Pengpu town government built a community-consultation platform to encourage community residents’ participation and co-ordinate the problems in community renewal. As for the elevator installation project, in addition to the relevant policies to guide community residents, the government also provided financial subsidies and assisted in elevator installation.

Since 2011, Shanghai has continuously issued a series of policies to support the installation of elevators in existing multi-story residences. Before 2014, the government regarded elevator installation as a real-estate development project, so the relevant procedures required for installing elevators were as complicated as residential-district development [40]. In addition, stakeholders, such as residents and developers, were unfamiliar with elevator-installation projects. All these factors stranded the “6 + 1” model. The Shanghai Finance Bureau (SFB) issued the “Notice Regarding Matters Related to Government Subsidies for Pilots of Installing Elevators in Existing Multistory Residences of Shanghai” in 2014, noting that “after the completion and acceptance of the elevator installation project, the government will subsidize 40% of the cost of installing elevator. Each elevator will not exceed 240,000 yuan, and the city government, district/county government will bear 50%, respectively” [86]. The release of this policy eases the financial burden of residents in installing elevators of existing multi-story residences and relatively reduces the difficulty of installing elevators. In 2016, the “Notice on Approval of Construction and Management of Elevators in Existing Multistory Residences in Shanghai” was issued to reduce the number of approvals for installing elevators from 46 to 15 and to shorten the time limit for approval of related materials to 52 working days [85]. Shanghai then issued the “Guide to Installing Elevators in Existing Multistory Residences” in March 2018, in which the points of design, elevator selection, implementation process, service guide, and reference figures and tables were explained in detail.

The issuance of these three policies and documents reduced the difficulty of installing elevators in Yuanlong in terms of funding, applications, and operations. Various government departments, including the Housing Management Bureau (HUB), Land and Resources Bureau (LRB), and Construction and Communications Commission (CCC), were also responsible for approving various application materials for installing elevators.

In addition, according to the policy issued by the SFB in 2014, after the completion and acceptance of the elevator installation project, the Shanghai Municipal Government and the Jing’an District Government provided a total of CNY 240,000 in subsidies for Yuanlong [86]. This was an indispensable prerequisite for the installation of elevators in Yuanlong.

The Pengpu town government also provided assistance in installing elevators in Yuanlong. Aiming at the parking problem encountered during the elevator installation of Yuanlong, the Pengpu town government actively contacted the stores around Yuanlong to provide free parking for the residents of Yuanlong. When solving the problem of an “electric wire shift”, the Pengpu town government also helped to co-ordinate matters, which promoted the smooth installation of elevators in Yuanlong.

4.2.3. Active Assistance of 3C and Third Parties

The success of elevator installation in Yuanlong is inseparable from the active assistance of the 3C and third parties. This article defines the neighborhood committee, owners committee, and property-management company as 3C, and enterprises, construction teams, and the media as the third parties of community renewal.

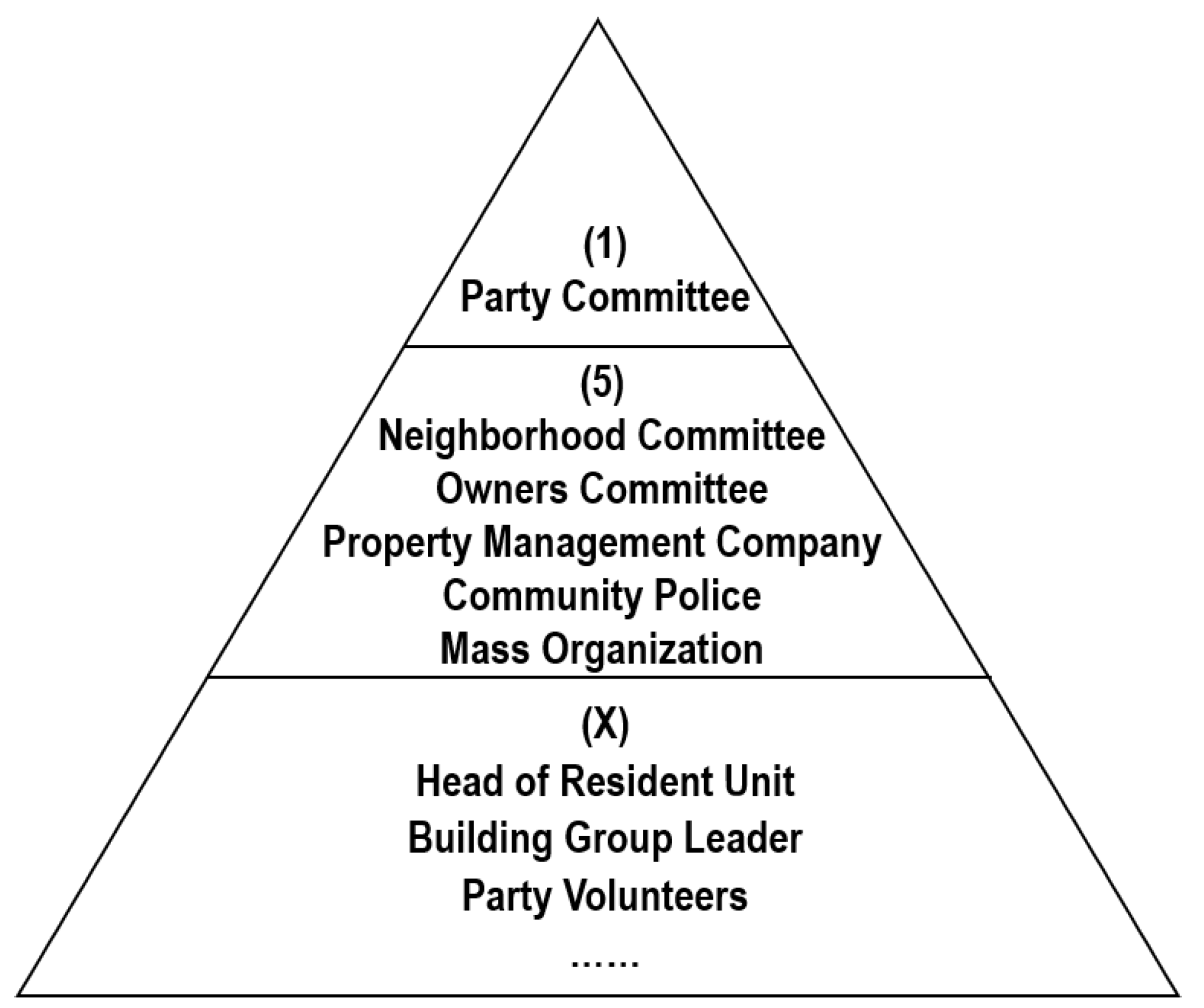

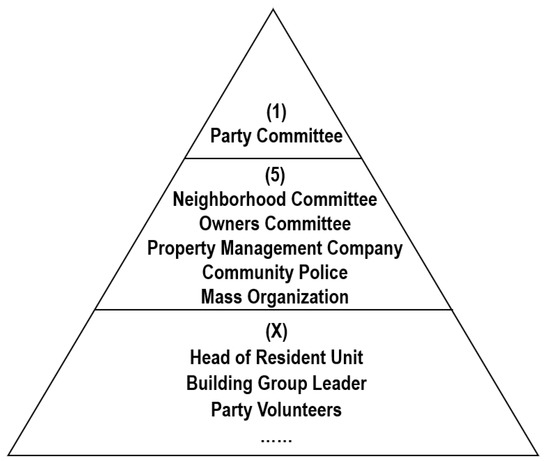

3C are the management and service organizations in the community that are essential for community renewal. When the owners’ committee and property-management company of Yuanlong turned to the neighborhood committee to solve the parking problem, the neighborhood committee immediately invited the relevant departments of Pengpu Town, property managers, members of the owners committee, police, and representatives of the co-construction units to hold the “1 + 5 + X” co-governance meeting (a negotiating platform for community renewal created by Jing’an District; Figure 3) to discuss the emergency plan. Through consultation, the final decision was to use the resources of the surrounding co-construction units to park according to the off-peak hours of employees, solving the parking problem of 14 cars, and smoothly starting the elevator-installation project [87]. The party branch secretary of Yuanlong (YW1) said:

Figure 3.

The “1 + 5 + X” co-governance meeting of the community-consultation platform.

“Yuanlong Apartment is relatively small, and many cars cannot be parked in the community because of its construction. We helped residents contact the surrounding units through the town government and neighborhood committee and let them park for free. Some cars were parked in Longtan Community (an adjacent community).”

When discussing the problem of electric wire shifting, the party organization of Yuanlong invited the members of the owners committee and the property manager of Longtan Community to hold an emergency “Trinity” meeting. Eventually, the owners’ committee and the property manager of Longtan Community agreed to knock out the garden perimeter but requested that it later be restored as before [87]. The electric-wire-shift problem that troubled Yuanlong was solved successfully, and the installation of elevators was carried out smoothly. These problems could not have been solved without the assistance of 3C.

A third party is essential for the success of community renewal. It is difficult for enterprises to enter the community and gain the trust of community residents. An enterprise must first obtain permission and assistance from the 3C. After entering the community, the enterprise needs to gain the trust of the community’s residents. Generally, residents have a wait-and-see attitude toward enterprises entering the community, and there will be various considerations when it comes to funding. The elevator company even set up an elevator-installation service center near Yuanlong, providing after-sales and consulting services for Yuanlong and residents of other communities [87].

In community renewal, the construction team needs to solicit residents’ opinions on the construction plan and inform residents of the project’s expected effects and possible problems. When encountering problems during construction, they must also negotiate with residents to solve them.

During the entire process of installing elevators in Yuanlong, the media made some in-depth reports on elevator installation that attracted the attention of the Land, Resources and Housing Bureau of Dalian, which played a role in promoting the success of elevator installation in Yuanlong.

Under the co-governance of the government, residents, neighborhood committee, owners committee, property-management company, enterprises, construction team, and media, Yuanlong’s elevator installation was completed on 18 January 2019, and all five elevators were delivered. Yuanlong Apartment became the first community in Shanghai where all elevators were successfully installed.

4.3. Results of Elevator Installation in Yuanlong Apartment

During the entire process of installing elevators in Yuanlong, the residents and government, neighborhood committee, owners committee, property-management company, elevator company, construction team, and media conducted multiple consultations and communicated. The success of the project encouraged residents to participate actively in community activities. The party secretary of Yuanlong (YW1) said:

“In the past, the residents of Yuanlong generally did not participate in community activities. Through this project, residents are now more actively participating in community activities, such as the election of the neighborhood committee last year (2018), election of the Longtan Owners Committee this year (2019), and garbage classification. In the past, residents were bystanders. Now they are actively participating, and some volunteers come out on duty every day to supervise garbage classification. Additionally, residents are very active and voluntary during the COVID-19 pandemic. We are now doing the ‘beautiful Louzu’ (each building is considered one Louzu) activities, which need to clear the corridor heap, and the residents are very cooperative. The relationship between the residents is also better. Elevator installation is a project that unites the hearts of the residents.”

To facilitate residents in using wheelchairs, movable accessibility facilities were prepared for each building. The elevator corridors were carefully decorated by the residents (Figure 4a). When referring to neighborhood relations, one resident interviewed (YM7) said:

Figure 4.

Effects of successful elevator installation in Yuanlong Apartment: (a) well-decorated elevator corridor; (b) stairwell for discussion. Sources: authors’ photographs.

“Since the elevators were installed, the relationship between the residents has become much better. A discussion corner was built in the corridor on the first floor. Sofas and chairs were provided to us by the neighborhood committee (Figure 4b). We often meet there to discuss things.”

Owing to reports from the news media, the experience of installing elevators in Yuanlong has been followed by many other communities. According to statistics, Shanghai completed the installation of 1579 elevators in 2021 and is expected to install more than 2000 elevators in 2022, greatly aiding the elderly in going downstairs [88].

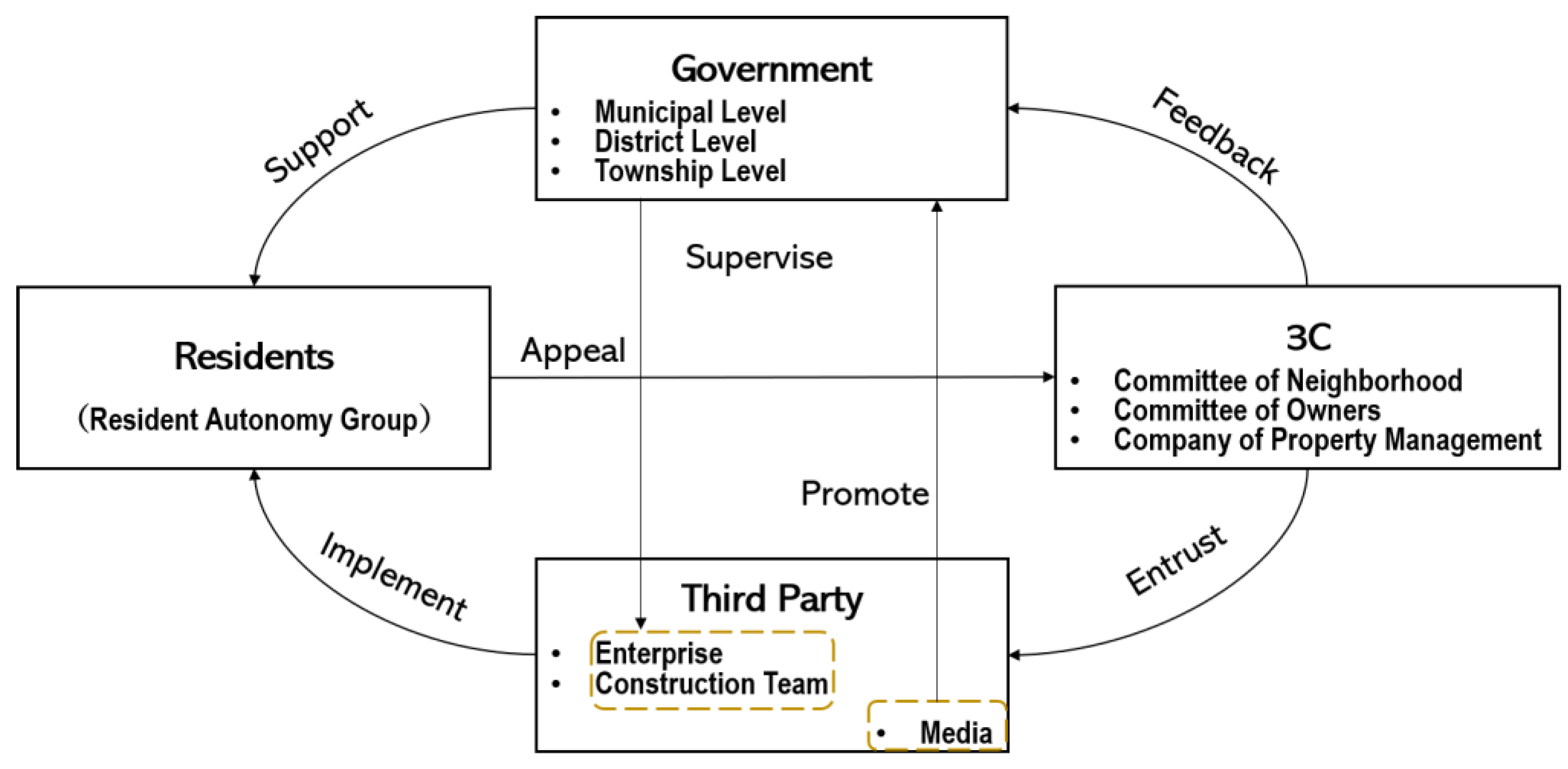

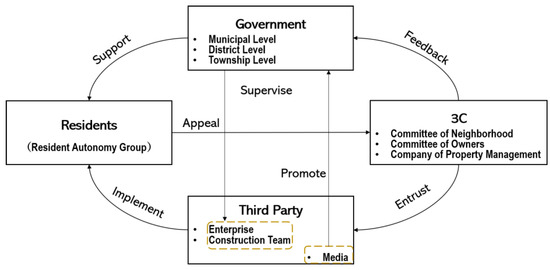

Multi-stakeholder co-governance is an important way to promote community renewal, which breaks the previous government-led model of community renewal and reflects the co-governance of multiple stakeholders, such as residents and the government, neighborhood committees, owners’ committees, property-management companies, enterprises, construction teams, and the media. This is fully reflected in the micro-case of the elevator installation in Yuanlong Apartment, Shanghai. In community renewal, none of the multiple stakeholders have rights of domination and decision; instead, they must interact with each other (Figure 5). Residents participated in the entire community-renewal process. The actions of the government, 3C, and third parties were mainly to meet residents’ needs. In community renewal, multiple stakeholders negotiate, co-operate, and co-ordinate with each other to jointly solve problems, thereby achieving community renewal.

Figure 5.

The mechanism of multi-stakeholder co-governance in community renewal.

5. Discussion

The community-renewal case of Yuanlong Apartment indicates that the key to multi-stakeholder co-governance is the co-ordination of the interests of different stakeholders. For example, high-rise residents who install elevators benefit the most, while low-rise residents not only have less demand for installing elevators, they also need to bear the risks of limited ventilation and lighting and the lower house-market value caused by installing elevators. Therefore, when co-ordinating their interests, high-rise households bear more cost sharing, first-floor households do not bear the costs of elevators, and second-floor households only bear part of the operating cost of elevators. In addition, although a good balance has been reached in cost sharing, some residents may be psychologically unbalanced, which will have a negative and subtle effect on the sense of community belonging of these residents and their relationship with neighbors. These factors should be considered first in the interest of the co-ordination of community renewal. Adhering to the principle of “equal advantage” and “compensation sharing” to ensure the maximum degree of co-ordination of material interests, it is also necessary to consider the psychological balance of residents and respect the rights and interests of each person in the community [89].

Community residents are the main body of community renewal, and their opinions and participation largely determine the community-renewal project [38]. Due to differences in age, educational level, and understanding of community-renewal projects, residents’ participation capabilities and enthusiasm are also different. These factors affect the difficulty and effectiveness of community renewal. The active participation of members of the joint construction group in Yuanlong attracted the gossip of some residents, which led to the dissolution of the group after elevator installation was completed. However, the dissolution of the group and the gossip that members suffered also led to some residents’ concerns about participating in community affairs, thus reducing their enthusiasm for community participation.

Public goods are extremely prone to the “free-riding” problem, which is a potential hazard to neighborhood relationships in the community [90]. Taking the installation of elevators as an example, some residents disagreed with elevator installation, did not sign the consent form, and did not participate in cost sharing, so there may have been a “free rider” problem, which may have led to embarrassing neighborhood relationships. Some residents even made it clear that those residents who did not participate in the cost sharing of the added elevators would not be considered when they wanted to generate funds in the future. Moreover, some high-rise residents who have added elevators are unhappy with cost sharing.

A resident in high-rise of Yuanlong (YW9) complains:

“Because of the structure of the house, we have a larger size so we paid more money. Originally, it was shared according to the floor, but later there were some quarrels saying that it should be according to the area of the house: the bigger the house, the more money they should pay. We had a bigger house than they did, so we paid more just to make sure the elevator was installed faster.”

The follow-up management of elevators installed in Yuanlong is also worth considering. The operating cost of the elevators installed in Yuanlong is paid based on the proportion agreed upon by the residents at the time of consultation, which will be charged by the building group leader every month. The elevator company promises to provide free maintenance for five years, so no maintenance fee is charged to the residents. However, after five years, whether the elevators’ follow-up management is self-managed or handed over to the property-management company needs to be verified through actual operation.

The party secretary of Yuanlong (YW1) worried that:

“(The installation of) the elevator is a recent work, the follow-up management is a big problem, many people want to hand over it to the property company, but there are no government documents. There is no standard for the takeover of property companies to refer to, and whether the property company is willing to take it over is also a problem. Five years from now, if there are problems with the elevators, the government and the community will need to jointly explore how to solve the problems.”

Most of the relevant regulations of government departments on community renewal are complicated, which adds many difficulties to community-renewal projects. Owing to conflicts between the “6 + 1” model and relevant laws and regulations, the elevator installation project was put on hold. The second attempt took three years to succeed. Moreover, when interviewing the Party Secretary of Yuanlong, many people in charge of the community called to ask about the specific operation of installing elevators. Therefore, relevant policy regulations regarding community renewal should be further adjusted. In addition, many old communities in Shanghai need to install elevators, but the government’s resources are limited. Therefore, whether the subsidy policies and government measures are sustainable and fair requires further research.

In fact, it is feasible to achieve multi-stakeholder co-governance even under the government-led mode. Whether it is the consultation of the willingness to install elevators in the early stage, the cost sharing, or the problems encountered in the later construction, or the issues of subsequent management of the elevators in the future, the residents of Yuanlong resolved these issues through independent consultation. Compared to the government-led model, this model satisfies residents’ needs to a great extent and reduces contradictions and friction, which is conducive to project implementation. However, the model requires capable and prestigious residents to lead voluntarily; otherwise, success will be difficult to achieve [78,80].

In addition, not only the spatial renewal of communities, but also the social benefits and sustainable development behind it, are issues worthy of consideration, such as the cultural continuity brought by community renewal [25,46], the cultivation of social capital [23,63,71], and the contradiction between the diversification of residents’ needs and insufficient environment space. These topics require further exploration.

Community renewal is always in progress. This study only examined the case of elevator installation in the community; there are still deficiencies in the analysis and discussion of the mechanism of multi-stakeholder co-governance in community renewal. Further research should be conducted with more cases.

6. Conclusions

Community renewal involves multiple stakeholders who require consultation and interest co-ordination among multiple stakeholders. The typical case of installing elevators in Yuanlong reflects the community renewal of multi-stakeholder co-governance outside of the government-led pattern. Residents set up an elevator installation group on their own to negotiate with the government, 3C, and third parties on elevator installation on behalf of the community residents. The government has changed its role in the installation of elevators from the previous goal of “taking on all things” to “support and guidance”, providing policy guidance and financial subsidies starting from the needs of residents. Furthermore, 3C and the third parties negotiated and communicated with residents and the government, which promoted the process of community renewal. The negotiation and co-governance of multiple stakeholders not only contributed to the successful installation of elevators in Yuanlong but also provided experience for community renewal of multi-stakeholder co-governance.

Although community renewal in China has made great progress, it still faces many challenges. The installation of elevators can reflect some important aspects of community renewal, particularly the co-ordination of the interests of multiple stakeholders. Communication, consultation, and co-operation between different stakeholders are needed to establish a fair and just interest-co-ordination mechanism. At the same time, the specific interest co-ordination mechanism should be adjusted according to the actual situation of the communities, and the opinions of all stakeholders, especially residents, should be sought.

Community renewal based on multi-stakeholder co-governance needs to be developed based on the specific conditions of communities. The case study of this article, though a micro-scale case in the inner city of a metropolis, could serve as a reference for the community renewal of other countries or cities because it provides a different path. Due to the complex co-ordination of interests among multiple stakeholders in community renewal projects, co-governance is usually difficult. Therefore, multidisciplinary, multi-method integration and multiple perspectives are required in future research. In addition, the community-renewal case in this study is of only one type. In the future, we can compare and summarize different types of co-governance in community renewal and further explore the co-ordination of interests and co-operative governance among multiple stakeholders. The stakeholders in community renewal also include social organizations, planners (teams), and others. With the emergence of more stakeholders, community co-governance will become a changing but worthwhile era, and further research is required in the future. Community renewal is a long-term process, and the satisfaction of community residents after renewal is an interesting question worthy of further study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and C.Y.; methodology, S.L. and Z.L.; software, Z.L.; validation, S.L., Z.L. and C.Y.; formal analysis, S.L. and C.Y.; investigation, S.L.; resources, Z.L.; data curation, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, S.L., Z.L. and C.Y.; visualization, Z.L.; supervision, Z.L.; project administration, C.Y.; funding acquisition, C.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Major Program of National Social Science Foundation of China (grant number 19ZDA086).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because issues of human privacy were not involved.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Personal information of interviewees.

Table A1.

Personal information of interviewees.

| Interview Coding | Total Number of Interviewing | Interview Date | Identity Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| YW1 | 3 | 30 June 2019 12 July 2019 9 March 2021 | Secretary of the Community Party Headquarters |

| YW2 | 1 | 12 July 2019 | Neighborhood-committee cadres; member of the joint construction group for adding elevators; community resident |

| YM3 | 1 | 12 July 2019 | Neighborhood-committee cadres |

| YM4 | 1 | 12 July 2019 | Community building leader |

| YW5 | 2 | 30 June 2019 9 March 2021 | Member of the joint construction group for adding elevators |

| YW6 | 1 | 30 June 2019 | Head of elevator company |

| YM7 | 1 | 12 July 2019 | Community resident |

| YW8 | |||

| YW9 | 1 | 9 March 2021 | Community resident |

| YM10 |

Notes: Code Y represents Yuanlong Apartment; code W/M represents female/male, and the code number represents the serial number of the interviewee. Total Number of Interviewing represents the number of interviews of each interviewee.

Appendix B

Table A2.

Interview outline of elevator installation in Yuanlong Apartment.

Table A2.

Interview outline of elevator installation in Yuanlong Apartment.

| I. Outline of the Interview with Neighborhood Committee |

|

| II. Outline of the Interview with Joint Construction Group Members/Ordinary Residents |

|

| III. Outline of the Interview with the Third Party |

|

References

- Adams, D.; Hastings, E.M. Urban renewal in Hong Kong: Transition from development corporation to renewal authority. Land Use Policy 2001, 18, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.K.L.; Chan, E.H.W. Factors affecting urban renewal in high-density city: Case study of Hong Kong. J. Urban Plan Dev. 2008, 134, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.L.; Chen, T.; Wang, L.Y. Development course and policy evolution of urban renewal in western cities. Human Geog. 2009, 24, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W.; Shen, G.Q.P.; Song, Y.; Sun, B.X.; Hong, J.K. Neighborhood sustainability in urban renewal: An assessment framework. Environ. Plan B-Urban. 2017, 44, 903–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Shen, G.Q.P.; Wang, H.; Hong, J.K.; Li, Z.D. Decision support for sustainable urban renewal: A multi-scale model. Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Rohe, W.M. From local to global: One hundred years of neighborhood planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2009, 75, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzaho, A.; Richardson, B.A.; Strugnell, C. Resident well-being, community connections, and neighbourhood perceptions, pride, and opportunities among disadvantage metropolitan and regional communities: Evidence from the neighbourhood renewal project. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 40, 871–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.M.; Andrews, R.; Jorda, V. Do neighbourhood renewal programs reduce crime rates? Evidence from England. J. Urban Econ. 2019, 110, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tin, W.J.; Lee, S.H. Development of neighbourhood renewal in Malaysia through case study for middle income households in New Village Jinjang, Kuala Lumpur. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 32, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, J.X. Interpretation and Reconstruction of Housing Redevelopment in China—Towards a Just Space Production; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.B.; Zhang, J.X. The urban renewal evolvement since modern times and thought of nowadays China urban renewal. Urban Probl. 2003, 5, 015. [Google Scholar]

- Bromley, R.D.F.; Tallon, A.R.; Thomas, C.J. City centre regeneration through residential development: Contributing to sustainability. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 2407–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orueta, F.D. Madrid: Urban regeneration projects and social mobilization. Cities 2007, 24, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. Urban Renewal: A New Milestone in Urban Development; National Academy of Governance Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C.; Osborne, S.P. Local strategic partnerships, neighbourhood renewal, and the limits to co-governance. Public Money Manag. 2003, 23, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinetto, M. Who wants to be an active citizen? The politics and practice of community involvement. Sociology 2003, 37, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallon, A. Urban Regeneration in the UK; Routledge: Lond, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinhans, R. False promises of co-production in neighbourhood regeneration: The case of Dutch community enterprises. Public Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 1500–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.W. France SRU Law: Experience and lessons for social housing construction in China. Urban Plan. Int. 2015, 30, 42–48, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, A.E.G.; McCarthy, L. Urban management and regeneration in the United States: State intervention or redevelopment at all costs? Local Gov. Stud. 2009, 35, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W.; Xu, Y. Assessing the social impact of revitalising historic buildings on urban renewal: The case of a local participatory mechanism. J. Des. Res. 2015, 13, 125–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, S. Participatory neighborhood revitalization effects on social capital: Evidence from Community Building Projects in Seoul. J. Urban Plan Dev. 2018, 144, 04017025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Ma, X.Y.; Cai, Y.L.; Gao, F. The countryside under multiple high-tension lines: A perspective on the rural construction of Heping Village, Shanghai. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 62, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Ma, X.Y.; Gao, Y.; Johnson, L. The lost countryside: Spatial production of rural culture in Tangwan village in Shanghai. Habitat Int. 2020, 98, 102137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.Y.; Li, D.Z.; Feng, H.B.; Gu, T.T.; Zhu, J.W. AHP-TOPSIS-Based evaluation of the relative performance of multiple neighborhood renewal projects: A case study in Nanjing, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.N.; Yang, X.J.; Li, D.L. “Micro-transformation”: The renewal method of old urban community. Urban Dev. Stud. 2017, 24, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, B.; Li, Y.; Cao, X.L. Management dilemma and resolution ways for the old residential communities: Taking the old residential communities of Shanxi Province for example. Urban Probl. 2018, 7, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Daily Online. 170,000 Old Residential Areas in Cities and Towns to Be Renovated (Published by Authorities). 2019. Available online: http://politics.people.com.cn/n1/2019/0702/c1024-31207513.html (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Chinese Government Website. The Task of Rebuilding Old Residential Areas of This Year Has Been Overfulfilled. 2020. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-12/23/content_5572404.htm (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Chen, X.L.; Zhu, H.; Yuan, Z.J. Contested memory amidst rapid urban transition: The cultural politics of urban regeneration in Guangzhou, China. Cities 2020, 102, 102755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.J.; Jiang, M.; Lu, X.G.; Liu, X.T.; Liu, B.; Zhang, J.Q.; Wang, X.W.; Tong, S.Z.; Lei, G.C.; Wang, S.Z.; et al. Aboveground biomass and its spatial distribution pattern of herbaceous marsh vegetation in China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2021, 64, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.L.; Zhang, F.Z.; Liu, Y.Q. Beyond growth machine politics: Understanding state politics and national political mandates in China’s urban redevelopment. Antipode 2022, 54, 608–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ruan, T. Conflicts in the urban renewal of the historic preservation area—Based on the investigation of Nanbuting Community in Nanjing. In Recent Developments in Chinese Urban Planning; Pan, Q.S., Cao, J., Eds.; GeoJournal Library, 114; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.R.; Fei, J.Y. State-led urban community governance: The quadripartite interactions and non-judicial dispute settlement. J. Guangxi Univ. Natl. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 39, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.R.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Y.M. How society embrace society? Business instition’s intervention in community governance in urban China. J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 3, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.I.; Kuo, C. Community governance and pastorship in Shanghai: A case study of Luwan District. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 1260–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.J.; Yuan, Z.J.; Li, J.H. The influence of Asian Games Old City Renovation Projects on community residents in Guangzhou. Planners 2010, 26, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, D. Building ‘community’: New strategies of governance in urban China. Econ. Soc. 2006, 35, 530–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thepaper.cn. Community Renewal Exhibition|Shanghai Pengpu Town①: How Difficult It Is to Install an Elevator. 2019. Available online: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_3754095 (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- The Commission on Global Governance (CCG). Our Global Neighborhood; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Stoker, G. Governance as theory: Five propositions. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 1998, 50, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Chen, R.; Chen, M.; Ye, X. A new framework of regional collaborative governance for PM2.5. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2019, 33, 109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.M.; Ye, C. A logical framework of rural-urban governance from the perspective of social-ecological resilience. Prog. Geog. 2021, 40, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.; Johnston, R. Spatial scale and neighbourhood regeneration in England: A case study of Avon. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2003, 21, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. ‘Art in capital’: Shaping distinctiveness in a culture-led urban regeneration project in Red Town, Shanghai. Cities 2009, 26, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.H.; Xin, L. Redevelopment of urban villages in Shenzhen, China—An analysis of power relations and urban coalitions. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 426–434. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X.H.; Altrock, U. Struggling for an adaptive strategy? discourse analysis of urban regeneration processes—A case study of Enning Road in Guangzhou city. Habitat Int. 2016, 56, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhou, Y.L.; Liu, G.W. Comparison of critical success paths for historic district renovation and redevelopment projects in China. Habitat Int. 2017, 67, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Fan, H.Y.; Wei, M.; Yin, K.L.; Yan, J.W. From edible landscape to vital communities: Clover Nature School Community Gardens in Shanghai. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2017, 5, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.T.; Lan, Y.X. Social co-governance a solution originated from the legitimacy demands of multiple parties. China Nonprofit Rev. 2017, 9, 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, X.H.; Leung, H.H. Exploring participatory microregeneration as sustainable renewal of built heritage community: Two case studies in Shanghai. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Liu, Z.M. Rural-urban co-governance: Multi-scale practice. Sci. Bull. 2020, 65, 778–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E.; Schroeder, L.; Wynne, S. Institutional Incentives and Sustainable Development: Infrastructure Policies in Perspective; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Third Way: The Renewal of Social Democracy; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, M.D. Polycentricity and Local Public Economies; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.H.Y.; Ng, S.T.; Skitmore, M. Conflict or consensus: An investigation of stakeholder concerns during the participation process of major infrastructure and construction projects in Hong Kong. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.Z.; Qian, Q.K.; Visscher, H.J.; Elsinga, M.G.; Wu, W.D. The role of stakeholders and their participation network in decision-making of urban renewal in China: The case of Chongqing. Cities 2019, 92, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ren, J. Social governance community and its implementation institutions design. CASS J. Polit. Sci. 2020, 1, 45–56, 125–126. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Zhou, Y.L.; Liu, G.W. Key variables for decision-making on urban renewal in China: A case study of Chongqing. Sustainability 2017, 9, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, B.Q.; Ng, M.K. Urban regeneration and social capital in China: A case study of the Drum Tower Muslim District in Xi’an. Cities 2013, 35, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.W.; Wei, L.Z.; Gu, J.P.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Y. Benefit distribution in urban renewal from the perspectives of efficiency and fairness: A game theoretical model and the government’s role in China. Cities 2020, 96, 102422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, J.; Wu, D.; Tian, D. Study on Sustainable Renovation of Urban Existing Housing in China; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Verhage, R. Renewing urban renewal in France, the UK and the Netherlands: Introduction. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2005, 20, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Liu, Z.; Cai, W.; Chen, R.; Liu, L.; Cai, Y. Spatial production and governance of urban agglomeration in China 2000–2015: Yangtze River Delta as a case. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, A.; Basu, R.; Mukherjee, C. A game theoretic approach to optimize multi-stakeholder utilities for land acquisition negotiations with informality. Socio-Econ. Plan Sci. 2020, 69, 100717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, C.; Dennemann, A. Urban regeneration and sustainable development in Britain: The example of the Liverpool Ropewalks Partnership. Cities 2020, 17, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carley, M. Urban partnerships, governance and the regeneration of Britain’s cities. Int. Plan Stud. 2000, 5, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, A.C.; Jones, B. Governance and social capital in urban regeneration: A comparison between Bristol and Naples. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 767–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hui, E.C.M.; Chen, T.T.; Lang, W.; Guo, Y.L. From Habitat III to the new urbanization agenda in China: Seeing through the practices of the “three old renewals” in Guangzhou. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.W.; Shen, G.Q.P.; Wang, H. A review of recent studies on sustainable urban renewal. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, W.B.; Yau, Y. Weightings of decision-making criteria for neighbourhood renewal: Perspectives of university students in Hong Kong. J. Urban Regen Renew. 2009, 2, 238–258. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J. Re-examining the relationship between urban renewal and everyday life through Mapping Workshop. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2017, 5, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwaja, A.I. Is increasing community participation always a good thing? J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2004, 2, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.S. China’s moderate middle class: The case of homeowners’ resistance. Asian Surv. 2005, 45, 777–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Sheng, Z. Homeowners’ activism in Beijing: Leaders with mixed motivations. China Quart. 2013, 215, 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.R.; Tu, Y.; Wu, T. Selective intervention in dispute resolution: Local government and community governance in China. J. Contemp. China 2018, 27, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.R.; Wu, T.; Fei, J.Y. Flexible governance in China: Affective care, petition social workers, and multi-pronged means of dispute resolution. Asian Surv. 2018, 58, 679–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.Z.; Qian, Q.K.; Visscher, H.J.; Elsinga, M.G. Stakeholders’ expectations in urban renewal projects in China: A key step towards sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.N.; Liu, Y.T.; Liu, Z. Co-wisdom, co-strategy, and co-benefit: Urban regeneration and community governance in Guangzhou City. Urban Dev. Stud. 2019, 26, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai Bureau of Statistics (SBS). Shanghai Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Shanghai Housing and Urban-rural Construction Management Committee (SHURCMC). Elevators Have Been Installed in Old Houses in Shanghai, and 429 Houses Have Been Approved for Construction, 137 Elevators Have Been Completed and Put Into Operation. 2019. Available online: http://zjw.sh.gov.cn/zjw/gzdt/20190515/65223.html (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Shanghai Housing and Urban-Rural Construction Management Committee (SHURCMC). Notice on Approval of Construction and Management of Elevators in Existing Multi-Storey Residences in Shanghai. 2016. Available online: http://zjw.sh.gov.cn/zjw/gfxwj/20180911/3726.html (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Shanghai Finance Bureau (SFB). Notice Regarding Matters Related to Government Subsidies for Pilots of Installing Elevators in Existing Multi-Storey Residences of Shanghai. 2014. Available online: http://www.czj.sh.gov.cn/zys_8908/zcfg_8983/zcfb_8985/csjj/201509/t20150916_156547.shtml (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Thepaper.cn. Community Renewal Stroll|Discussion: How Do Community Negotiations Work. 2019. Available online: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_3983717 (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Thepaper.cn. Shanghai CPPCC|Gong Zheng: More than 2000 Elevators Will Be Installed for Old Houses this Year. 2022. Available online: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_16416881 (accessed on 16 April 2022).

- Ning, C.Q. Theoretical analysis of compensation sharing method for installing elevators in existing residence. Urban Probl. 2014, 5, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Noonan, D.S.; Richardson, L.E.; Sadiq, A.A.; Tyler, J. What drives community flood risk management? Policy diffusion or free-riding. Int. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2020, 15, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).