Social Media and the Pandemic: Consumption Habits of the Spanish Population before and during the COVID-19 Lockdown

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection Process

2.3. Instruments

3. Results

3.1. Access to and Frequency of Use of Technological Devices before and during the Lockdown

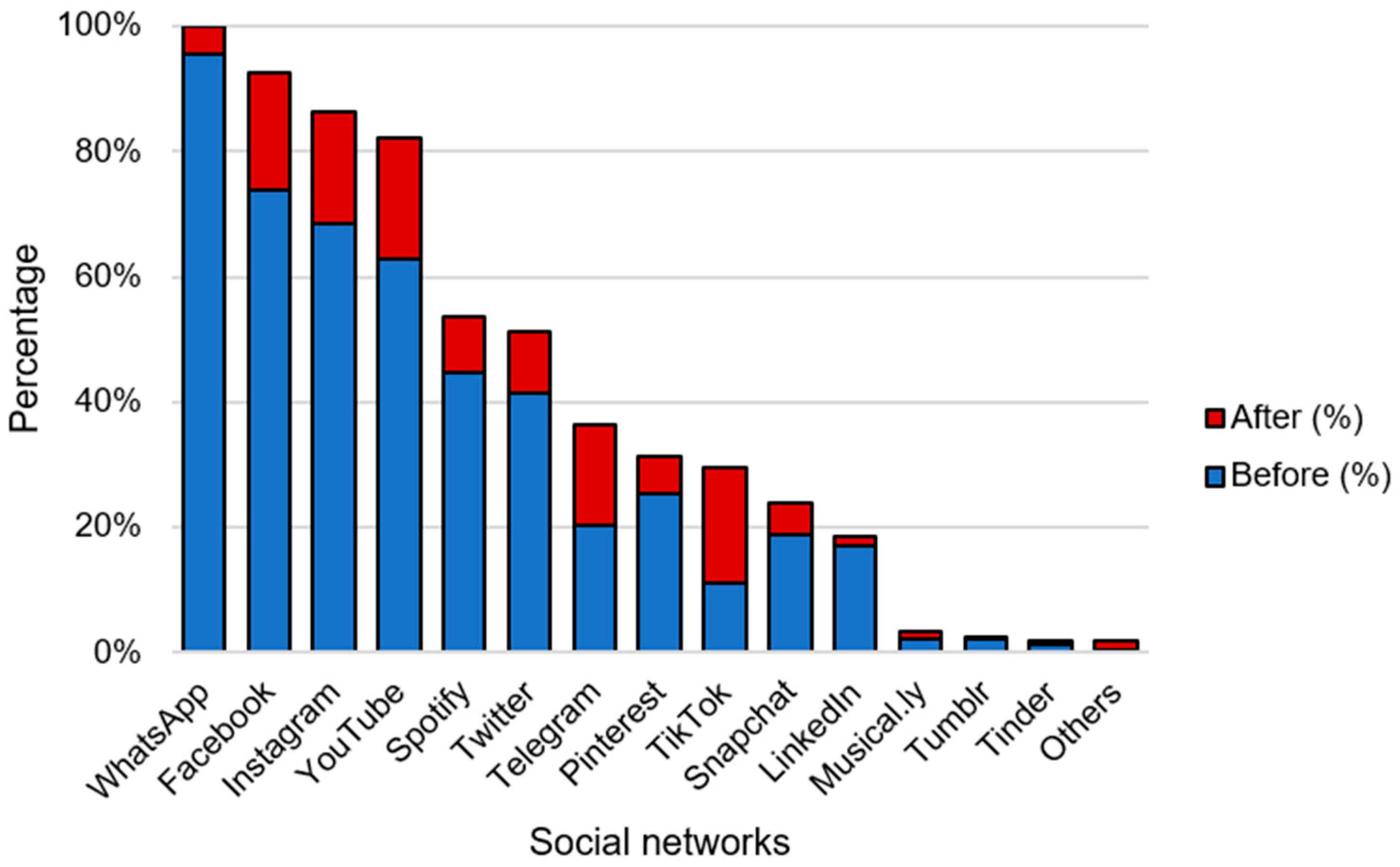

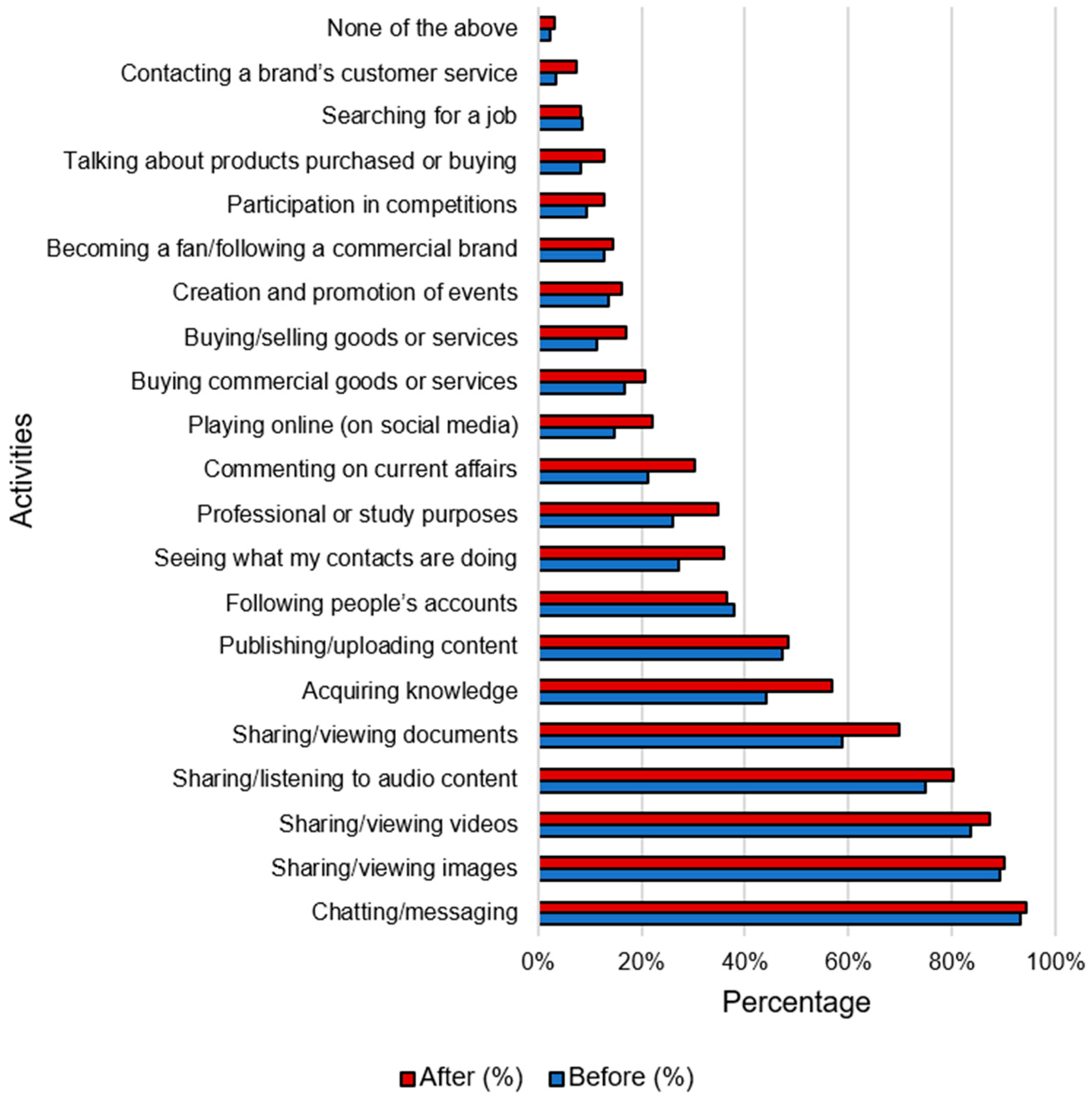

3.2. Registration, Frequency and Type of Use of Social Media

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

4.2. Practical Contributions

4.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McQuail, D.; Windahl, S. Communication Models for the Study of Mass Communication; Longman: Harlow, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tai, Z.; Sun, T. Media dependencies in a changing media environment: The case of the 2003 SARS epidemic in China. New Media Soc. 2007, 9, 987–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, M.; Karatas, K.; Arpaci, I. Psychological and socio-economic effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Turkish Population. In Emerging Technologies during the Era of COVID-19 Pandemic. Studies in Systems, Decision and Control; Arpaci, I., Al-Emran, M.A., Al-Sharafi, M., Marques, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Király, O.; Potenza, M.N.; Stein, D.J.; King, D.L.; Hodgins, D.C.; Saunders, J.B.; Griffiths, M.D.; Gjoneska, B.; Billieux, J.; Brand, M.; et al. Preventing problematic internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consensus guidance. Compr. Psychiatry 2020, 100, 152180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornmoen, H.; Backholm, K. Social Media Use in Crisis and Risk Communication: Emergencies, Concerns and Awareness; Emerald Group Publishing: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Diezhandino, M.P. Periodismo y Poder. Políticos, Periodistas y Ciudadanos Voluntariamente Desinformados; Pearson Prentice-Hall: Madrid, Spain, 2008; pp. 296–298. [Google Scholar]

- Rodero, E. Radio: The medium that best copes in crises. Listening habits, consumption, and perception of radio listeners during the lockdown by the COVID-19. Prof. Inf. 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, M.M.; Castellà, C.O.; Raso, M.L. Impacto de la pandemia de COVID-19 en el consumo de medios en España. Rev. Lat. De Comun. Soc. 2020, 78, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, R.K.; Fletcher, R.; Newman, N.; Brenne, J.S.; Howard, P.N. Navegando la ‘Infodemia’: Así Consume y Califica las Noticias y la Información Sobre el Coronavirus la Gente en Seis Países; Reuters Institute: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, N.S.; Hussain, Z.; Hamid, H.S.A.; Khairani, A.Z. Roles of social media and counselling support in reducing anxiety among Malaysian during COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 63, 102456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Yang, F.; Lu, X.; Hao, W. Internet Addiction and Related Psychological Factors among Children and Adolescents in China during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Epidemic. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Chen, W.; Liao, Y. Social media use in China before and during COVID-19: Preliminary results from an online retro-spective survey. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 140, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werling, A.M.; Walitza, S.; Grünblatt, E.; Dreschsler, R. Media use before, during and after COVID-19 lockdown according to parents in a clinically referred simple in child and adolescent psychiatry: Results of an online survey in Switzerland. Compr. Psychiatry 2021, 109, 152260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, T. The changes in the effects of social media use of Cypriots due to COVID-19 pandemic. Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, M.; Vassio, L.; Giordano, D. Debate on online social networks at the time of COVID-19: An Italian case study. Online Soc. Netw. Media 2021, 23, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemenager, T.; Neissner, M.; Koopmann, A.; Reinhard, I.; Georgiadou, E.; Müller, A.; Kiefer, F.; Hillemacher, T. COVID-19 Lockdown Restrictions and Online Media Consumption in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Andrío, R.; Bernal, C.; Palomero, I. Uso de las redes sociales entre los jóvenes y ciudadanía digital: Análisis tras la COVID-REIDICS. Rev. Investig. Didáctica Cienc. Soc. 2020, 7, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelazim, A.; Ajmi, Q.A.; AlBusaidi, H. The effect of Web 2.0 applications on the development of educational communication activities in teaching. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Lang. Stud. 2021, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qaysi, N.; Mohamad-Nordin, N.; Al-Emran, M. What leads to social learning? Students’ attitudes towards using social media applications in Omani higher education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 2157–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cívico, A.; Cuevas, N.; Colomo, E.; Gabarda, V. Jóvenes y uso problemático de las tecnologías durante la pandemia: Una preocupación familiar. Hachetetepé Rev. Científica Educ. Comun. 2021, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormes, J.M. Under the influence of Facebook? Excess use of social networking sites and drinking motives, consequences, and attitudes in college students. J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 5, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Torsheim, T.; Brunborg, G.S.; Pallesen, S. Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychol. Rep. 2012, 110, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; McPhetres, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.G.; Rand, D.G. Fighting COVID-19 Misinformation on Social Media: Experimental Evidence for a Scalable Accuracy-Nudge Intervention. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.-H.; Chen, C.-Y.; Pakpour, A.H.; Griffiths, M.D.; Lin, C.-Y. Internet-Related Behaviors and Psychological Distress among School children during COVID-19 School Suspension. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 159, 1099–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegmann, E.; Stodt, B.; Brand, M. Addictive use of social networking sites can be explained by the interaction of Internet use expectancies, Internet literacy, and psychopathological symptoms. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shaw, R.; Kim, Y.-K.; Hua, J. Governance, technology and citizen behavior in pandemic: Lessons from COVID-19 in East Asia. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 6, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, W.; Vidal-Alaball, J.; Downing, J.; Seguí, F.L. COVID-19 and the 5G Conspiracy Theory: Social Network Analysis of Twitter Data. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Rico, C.; González-Esteban, J.; Martínez-Hernández, A. Consumo de información en redes sociales durante la crisis de la COVID-19 en España. Rev. De Comun. Salud 2020, 10, 461–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K. 2019-nCoV, fake news, and racism. Lancet 2020, 395, 685–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, N.; Ortega, I. Generación Z: Todo lo Que Necesitas Saber Sobre los Jóvenes Que Han Dejado Viejos a los Millennials; Plataforma Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Interactive Advertising Bureau. Estudio Anual de Redes Sociales 2020; IAB: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qaysi, N.; Mohamad-Nordin, N.; Al-Emran, M. Employing the technology acceptance model in social media: A systematic review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 4961–5002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Hogares con Conexión a Internet. Indicadores de Equipamiento y Uso de TIC en los Hogares; INE: Cáceres, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Morduchowicz, R.; Marcon, A.; Sylvestre, V.; Ballestrini, F. Los Adolescentes y las Redes Sociales; Ministerio de Educación Presidencial de la Nación: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Trevisan, M.; Giordano, D.; Drago, I.; Munafo, M.M.; Mellia, M. Five Years at the Edge: Watching Internet from the ISP Network. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2020, 28, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Romay, E.; Mirón, S.G. Influencers y coronavirus. Los contenidos sobre la pandemia COVID-19 en las publicaciones de prescriptores de redes sociales en España (2020): El caso de Instagram. Quad. CAC 2020, 23, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Z.; Zhang, R.; Xiao, J. Passive social media use and psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of social comparison and emotion regulation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 127, 107050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age * | Gender | Count (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10–26 years (Generation Z) | Female | 105 (26.45%) | 151 (38.04%) |

| Male | 46 (11.59%) | ||

| 27–39 years (Generation Y) | Female | 54 (13.60%) | 75 (18.89%) |

| Male | 21 (5.29%) | ||

| 40–51 years (Generation X) | Female | 37 (9.32%) | 54 (13.60%) |

| Male | 17 (4.28%) | ||

| 52–71 years (Baby Boomer) | Female | 64 (16.12%) | 90 (22.67%) |

| Male | 26 (6.55%) | ||

| 72–90 years (Silent Generation) | Female | 10 (2.52%) | 27 (6.80%) |

| Male | 17 (4.28%) |

| Dimensions | Items | Total | Typology |

|---|---|---|---|

| (D1) Sociodemographic data | 1–7 | 7 | Closed dichotomous nominal (gender) and polytomous interval questions (age) |

| (D2) Use of social media before the lockdown | 8, 10, 11, 14 | 4 | Closed polytomous questions of a nominal nature with multiple-choice answers (several options may be chosen) |

| (D3) Use of social media during the lockdown | 9, 12, 13, 15 | 4 | Closed polytomous questions of a nominal nature with multiple-choice answers (several options may be chosen) |

| Total | 15 |

| Use | Moment | Smart Phone | PC | Laptop | Tablet | Smart TV | Smart Watch | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Before | 8 (2%) | 253 (63.7%) | 71 (17.9%) | 180 (45.3%) | 157 (39.5%) | 312 (78.6%) | 374 (94.2%) |

| During | 8 (2%) | 249 (62.7%) | 78 (19.6%) | 183 (46.1%) | 161 (40.6%) | 312 (78.6%) | 371 (93.5%) | |

| Less than 1 h | Before | 46 (11.6%) | 97 (24.4%) | 144 (36.3%) | 130 (32.7%) | 66 (16.6%) | 52 (13.1%) | 15 (3.8%) |

| During | 13 (3.3%) | 62 (15.6%) | 59 (14.9%) | 72 (18.1%) | 37 (9.3%) | 44 (11.1%) | 10 (2.5%) | |

| 1 to 2 h | Before | 100 (25.2%) | 21 (5.3%) | 88 (22.2%) | 55 (13.9%) | 92 (23.2%) | 10 (2.5%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| During | 62 (15.6%) | 24 (6%) | 43 (10.8%) | 58 (14.6%) | 55 (13.9%) | 12 (3%) | 7 (1.8%) | |

| 2 to 3 h | Before | 131 (33%) | 9 (2.3%) | 49 (12.3%) | 23 (5.8%) | 55 (13.9%) | 9 (2.3%) | 3 (0.8%) |

| During | 135 (34%) | 31 (7.8%) | 95 (23.9%) | 47 (11.8%) | 83 (20.9%) | 8 (2%) | 4 (1%) | |

| 3 to 5 h | Before | 72 (18.1%) | 7 (1.8%) | 30 (7.6%) | 8 (2%) | 19 (4.8%) | 4 (1%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| During | 90 (22.7%) | 15 (3.8%) | 52 (13.1%) | 20 (5%) | 32 (8.1%) | 7 (1.8%) | 1 (0.3%) | |

| More than 5 h | Before | 40 (10.1%) | 10 (2.5%) | 15 (3.8%) | 1 (0.3%) | 8 (2%) | 10 (2.5%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| During | 89 (22.4%) | 16 (4%) | 70 (17.6%) | 17 (4.3%) | 29 (7.3%) | 14 (3.5%) | 4 (1%) | |

| Total | Before | 389 (98%) | 144 (36.3%) | 326 (82.2%) | 217 (54.7%) | 240 (60.5%) | 85 (21.4%) | 23 (5.9%) |

| During | 389 (98%) | 148 (37.2%) | 319 (80.3%) | 214 (53.8%) | 236 (59.5%) | 85 (21.4%) | 26 (6.6%) |

| Social Media | None | Less than 1 h | 1 to 2 h | 2 to 3 h | 3 to 5 h | More than 5 h | Total * | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | D | B | D | B | D | B | D | B | D | B | D | B | D | |

| 103 (25.9%) | 150 (37.8%) | 197 (49.6%) | 91 (22.9%) | 71 (17.9%) | 88 (22.2%) | 19 (4.8%) | 44 (11.1%) | 4 (1%) | 16 (4%) | 3 (0.8%) | 8 (2%) | 294 (74.1%) | 247 (62.2%) | |

| 17 (4.3%) | 83 (20.9%) | 84 (21.2%) | 30 (7.6%) | 127 (32.2%) | 85 (21.4%) | 76 (19.1%) | 90 (22.7%) | 52 (13.1%) | 57 (14.4%) | 41 (10.3%) | 52 (13.1%) | 380 (95.9%) | 314 (79.2%) | |

| YouTube | 131 (33%) | 173 (43.6%) | 134 (33.8%) | 67 (16.9%) | 76 (19.1%) | 54 (13.6%) | 34 (8.6%) | 66 (16.6%) | 16 (4%) | 25 (6.3%) | 6 (1.5%) | 12 (3%) | 266 (67%) | 224 (56.4%) |

| 127 (32%) | 171 (43.1%) | 99 (24.9%) | 59 (14.9%) | 69 (17.4%) | 57 (14.4%) | 52 (13.1%) | 50 (12.6%) | 34 (8.6%) | 28 (7.1%) | 16 (4%) | 32 (8.1%) | 270 (68%) | 226 (57.1%) | |

| 241 (60.7%) | 267 (67.3%) | 99 (24.9%) | 58 (14.6%) | 34 (8.6%) | 33 (8.3%) | 15 (3.8%) | 23 (5.8%) | 5 (1.3%) | 12 (3%) | 3 (0.8%) | 4 (1%) | 156 (39.4%) | 130 (32.7%) | |

| Spotify | 228 (57.4%) | 259 (65.2%) | 78 (19.9%) | 52 (13.1%) | 38 (9.6%) | 22 (5.5%) | 22 (5.5%) | 28 (7.1%) | 21 (5.3%) | 14 (3.5%) | 10 (2.5%) | 22 (5.5%) | 169 (42.8%) | 138 (34.7%) |

| 332 (83.6%) | 344 (86.6%) | 57 (14.4%) | 41 (10.3%) | 3 (0.8%) | 10 (2.5%) | 3 (0.8%) | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.5%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 65 (16.5%) | 53 (13.4%) | |

| 302 (76.1%) | 322 (81.1%) | 81 (20.4%) | 48 (12.1%) | 10 (2.5%) | 12 (3%) | 2 (0.5%) | 12 (3%) | 2 (0.5%) | 2 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 95 (23.9%) | 75 (18.9%) | |

| Telegram | 316 (79.6%) | 294 (74.1%) | 67 (16.9%) | 54 (13.6%) | 8 (2%) | 18 (4.5%) | 3 (0.8%) | 16 (4%) | 1 (0.3%) | 4 (1%) | 2 (0.5%) | 11 (2.8%) | 81 (20.5%) | 103 (25.9%) |

| Snapchat | 323 (81.4%) | 344 (86.6%) | 67 (16.9%) | 45 (11.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 4 (1%) | 3 (0.8%) | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.5%) | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.5%) | 74 (18.8%) | 53 (13.4%) |

| Tinder | 386 (97.2%) | 388 (97.7%) | 9 (2.3%) | 8 (2%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (2.9%) | 9 (2.3%) |

| Tumblr | 383 (96.5%) | 390 (98.2%) | 12 (3%) | 7 (1.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (3.6%) | 7 (1.8%) |

| Musical.ly | 384 (96.7%) | 385 (97%) | 7 (1.8%) | 6 (1.5%) | 4 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.5%) | 6 (1.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (3.3%) | 12 (3%) |

| TikTok | 355 (89.4%) | 303 (76.3%) | 21 (5.3%) | 43 (10.8%) | 10 (2.5%) | 20 (5%) | 7 (1.8%) | 18 (4.5%) | 3 (0.8%) | 11 (2.8%) | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.5%) | 42 (10.7%) | 94 (23.6%) |

| Other | 391 (98.5%) | 388 (97.7%) | 4 (1%) | 8 (2%) | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (1.6%) | 9 (2.3%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gudiño, D.; Fernández-Sánchez, M.J.; Becerra-Traver, M.T.; Sánchez, S. Social Media and the Pandemic: Consumption Habits of the Spanish Population before and during the COVID-19 Lockdown. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5490. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095490

Gudiño D, Fernández-Sánchez MJ, Becerra-Traver MT, Sánchez S. Social Media and the Pandemic: Consumption Habits of the Spanish Population before and during the COVID-19 Lockdown. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):5490. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095490

Chicago/Turabian StyleGudiño, Diego, María Jesús Fernández-Sánchez, María Teresa Becerra-Traver, and Susana Sánchez. 2022. "Social Media and the Pandemic: Consumption Habits of the Spanish Population before and during the COVID-19 Lockdown" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 5490. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095490

APA StyleGudiño, D., Fernández-Sánchez, M. J., Becerra-Traver, M. T., & Sánchez, S. (2022). Social Media and the Pandemic: Consumption Habits of the Spanish Population before and during the COVID-19 Lockdown. Sustainability, 14(9), 5490. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095490