1. Introduction

Affected by the COVID-19 epidemic and the unstable world situation, global cross-border investment has been hit hard in recent years. According to a report from UNCTAD in 2020, global cross-border investment has fallen to its lowest level since 2005. The number of restrictive investment policies published in 2020 reached at an all-time high. Outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) has been proved to be an important way for emerging countries to seek knowledge spillover and to improve their technology. However, the global trend of investment protectionism and the severe health crisis have made emerging countries face more serious sustainable development issues. Therefore, how to improve the efficiency of technology spillover from the multinational enterprises (MNEs) of developing country through OFDI is an urgent question.

According to recent data, China’s outward investment stock reached USD 1.98 trillion in 2018, ranking third in the world. In addition, China’s OFDI in tertiary industries, especially in science- and technology-intensive fields, has soared sharply, accounting for more than 70% of the total foreign investment stock. These data imply that the purpose of Chinese foreign investment has shifted from exploring natural resources and opening up additional markets to acquiring knowledge and innovation from foreign countries. Therefore, this paper chooses Chinese MNEs as a sample through which to study the influencing factors of OFDI MNEs’ innovation performance.

Multiple scholars tend to analyze this question from the perspective of OFDI reverse technology spillovers. In existing research, the reverse technology spillover effect is used to describe the phenomenon that OFDI in knowledge-intensive developed markets will positively affect the technological capabilities of the parent MNEs in emerging countries [

1]. The existing research on the factors contributing to the spillover effect mainly include three aspects; namely, China’s absorptive capacity [

2], enterprise-based activities [

3], and the characteristic differences between the home country and host country [

4]. Institutional distance, an essential aspect of heterogeneity between the home country and host country, also serves as one of the elements that can be used to build a comparative advantage in traditional international trade theory [

5]. Therefore, introducing institutional distance into the research framework of reverse technology spillover has a certain theoretical basis and relevance. Nonetheless, in extant research, scholars mostly focus on the influence of rigid constraints, such as technology gaps and economic development disparity [

6], and pay less attention to the relationship between institutional distance and innovation performance. Even though some researchers have noticed institutional factors, their research is simply centered on the impact of institutional quality [

7].

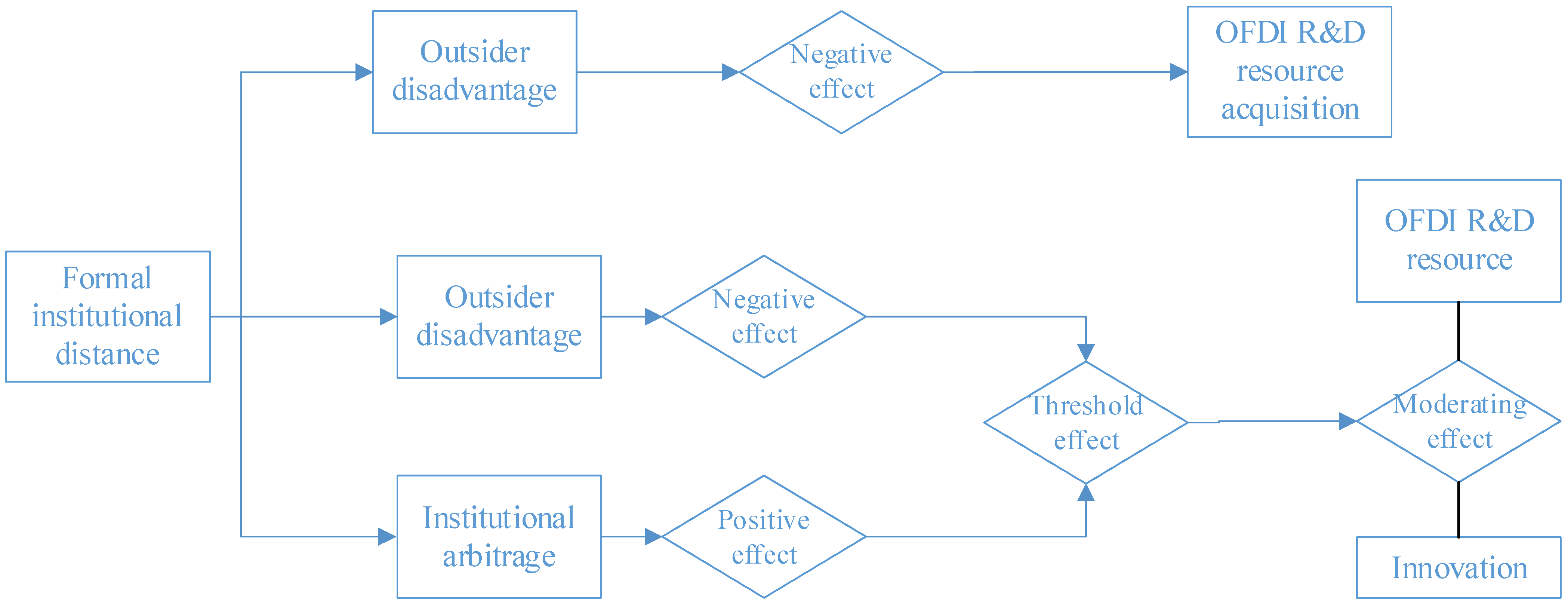

There are two different perspectives explaining how institutional distance shapes innovation performance of parent MNEs from developing economies. From the perspective of outsider disadvantages, MNEs from developing economies encounter higher institutional complexity in distant host countries that can demotivate these companies to engage in innovation activities and magnify the difficulties of achieving any innovation outcomes [

8,

9]. Therefore, outsider disadvantages perspective predicts negative effects of institutional distance on innovation performance of MNEs from developing economies.

However, from the institutional arbitrage perspective, different institutional environments in host countries may provide OFDI companies more favorable business environments that could promote their innovation activities [

10]. This is especially true for MNEs from developing economies where the market mechanisms in their home country is rudimentary or immature, and home-country governments are less efficient in providing high-quality public services, thereby forcing these companies to conduct OFDI as a way to “escape” unfavorable home market to operate in more munificent host countries [

11]. Moreover, institutional distance can also provide firms more diversified knowledge that can contribute to innovation performance.

Reconciling these two different perspectives, this paper innovatively differentiates two stages of the reverse technology spillover effect, namely the OFDI R&D resources acquisition and the transformation from OFDI R&D resources to innovation performance, and we examine the differential roles of institutional distance in these two stages. Empirical analyses based on data of China’s OFDI in 28 major trading partners from 2003 to 2017 largely support our propositions.

This study contributes to the literature on OFDI reverse technology spillover effect in three ways: first, we provide a more comprehensive measure of institutional distance based on the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), which expands the current discussion on technology gaps and economic development disparity. Second, by dividing the reverse technology spillover process into two stages, we provide more fine-grained perspectives on the effects of institutional distance, and, to a certain extent, reconcile the conflicting views on the relationship between institutional distance and innovation performance. Third, using the more advanced threshold regression method, we provide empirical evidence on the nonlinear moderating effects of institutional distance in the OFDI R&D resource utilization process.

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews relevant literature and develops hypotheses. In

Section 3, the methodology, as well as a description of the data, the measurement of the variables, and the empirical strategy, is presented.

Section 4 presents the main results.

Section 5 discusses our main findings, as well as theoretical and practical implications, and draws conclusions of this paper.

3. Method

3.1. Data and Sample

Our paper selects China as the investment home country sample to study the FID and innovation performance of OFDI firms. The reasons for this are as follows: first of all, China represents an emerging market with the largest OFDI stock and has sufficient OFDI practices that covers a wide range of host countries, allowing us to collect a large amount of available host country data and investment cases for research during the analysis. Moreover, having witnessed its market-oriented development trajectory with continuous improvements and changes at the institutional quality level over the past four decades, China, a surging emerging country, provides a favorable background for this study to examine how multinational enterprises respond to changes in the FID. Moreover, the purpose of this study is to provide certain policy recommendations for Chinese OFDI firms to promote their internationalization.

Given the availability and objectivity of the data, we selected the countries to which most of China’s OFDI went to from 2003–2017 to represent the host country sample according to the Statistical Bulletin of China’s OFDI. The China OFDI Statistical Bulletin, which is jointly prepared by the Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, the National Bureau of Statistics, and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange, introduces an overview of OFDI and a data report on the investment situation of major economies in the world with high authenticity and authority. In this paper, the main economic variables and WGI variables from the World Bank database and OECD Main Science and Technology Indicators for the sample countries are combined to obtain the basic data to support this study. This paper excludes host countries that are obvious tax havens from the sample and also excludes countries with a large number of missing data, and the countries with OFDI flows of less than 1%, obtaining a final sample of 28 host countries. Among them are 18 developed countries, namely Denmark, Norway, Sweden, New Zealand, Canada, Czech Republic, Germany, Spain, Finland, France, the UK, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, The Netherlands, the US, and Singapore, and 10 developing countries, specifically, Chile, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Mexico, Poland, Greece, Portugal, and Turkey. According to the 2018 Annual China Outward Foreign Direct Investment Statistical Bulletin, China’s OFDI in the above countries accounts for more than 70% of the total amount, proving the representability of the sample selection.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Dependent Variables

The innovation performance of the OFDI MNEs was used as the dependent variable and denotes IP. This was proxied by the whole number of valid patents applied by Chinese MNEs in each host country during the period of 2003–2017. The number of valid patents was estimated using the World Intellectual Property Organization database. This method effectively measures the innovation completed by the subsidiary in the OFDI host country and, to a certain extent, simultaneously controls the mutual influence between companies.

3.2.2. Independent Variable

FID (FID)

To measure our key independent variable, the FID, the six World Governance Indicators (WGI) of the World Bank were used to explain the FID [

33]. This indicator measures the effectiveness of government governance from six perspectives. The six factors are “voice and accountability” (voice), “political stability and absence of violence” (sta), “government effectiveness” (gov), “regulatory quality” (rq), “rule of law” (rule), and “control of corruption” (control).

After the variables for the

FID were obtained, the Kogut–Singh index [

34] of distance was used to estimate the value of the

FID and was calculated as follows:

where

represents the

FID between host country

j and China;

i is a variable;

is the

ith variable value of the

jth country;

is the

ith variable value of China; and

suggests the variance in the index under the

ith dimension.

OFDI R&D Resource Acquisition (Sf)

This paper uses the total amount of OFDI R&D resource acquired per year to measure the OFDI R&D resource acquisition capacity, which can be calculated as follows [

4]:

where

represents the stock of foreign R&D resources obtained by China from OFDI in country

j in year

t;

denotes the stock of OFDI in country

j by China in year

t;

refers to the local stock of R&D resources in country

j in year

t; and

is the fixed assets index of country

j in year

t. The perpetual inventory method is employed to calculate

, and the calculation formula is:

where

is the depreciation rate, which is 5% in accordance with the method of Han and Wang [

4]. Concurrently, the calculation method uses 2003 as the base period for determining the R&D resource stock, and

signifies the amount of R&D resource expenditures in country

j in year

t. To eliminate the impact of price changes, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for the year 2000 as the base period and the fixed asset formation index of each country

were chosen for conversion. In this paper, the host country’s R&D resource stock, fixed asset formation, and fixed asset formation index are all from the OECD Main Science and Technology Indicators database.

Control Variables

Selected from relevant literature and models, several control variables are introduced to reduce confounding effects. With regard to technology spillover, the host country’s related condition will have an impact on the innovation performance of the subsidiaries of OFDI [

35]. In this paper, we controlled the human resource level, innovation intensity, trade openness, economic distance, and market size (

Table 1). These variables have been considered to be factors that influence the transmission paths of technology spillover and have been deemed to affect the innovation performance of OFDI subsidiaries by interfering with the technology density of the host country and the difficulty of exchanging OFDI information in previous studies.

Human Resource Level (HR)

In the OFDI process, the employment of labor in the host country by subsidiaries is considered to be an important way to acquire knowledge spillover [

3]. Therefore, the quality of labor in the host country is an important factor affecting the knowledge spillover process. We use the proportion of the population with higher education to measure the human resource level.

Innovation Intensity (IPP)

Higher innovation intensity represents a better innovation environment in the host country and easier access to knowledge spillover from local sources by subsidiaries. R&D investments are crucial for firms who are engaged in innovation activities; they are also an important means to improve a firm’s innovation capabilities, so this paper uses the log of the proportion of R&D expenses in revenue to measure the innovation intensity.

Trade Openness (Open)

A country’s degree of trade openness can reflect its acceptance of foreign investment, and the greater the degree of trade openness, the fewer restrictions on foreign investment, and the easier it is for OFDI MXEs to obtain knowledge spillover. This paper uses the log of the proportion of the import and export trade volume in the GDP in the host country to measure the trade openness.

Economic Distance (ED)

Previous studies in the literature have proven that the various differences between the home country and the host country will have certain impacts on the difficulty of technology spillover [

24]. The difference between better empirical test results was chosen as the control variable to control the influence of the difference between the home country and the host country except for the FID. The disparity in the economic development level of the two countries may manipulate the difficulty and transmission path for reverse technology spillover in OFDI. The smaller the gap in the economic development level, the more similar the stage of development between two countries and the consumption habits of their residents are, which helps to remove the obstacles to obtaining OFDI technology spillover. The absolute value of the difference between the per capita GDP of the host country and the home country is utilized herein to measure the distance between the economic development levels of the two countries.

Market Size (Size)

Market size is a frequently used control variable in OFDI studies, and this paper uses the log of the population in the host country to measure the market size.

3.3. Analysis of Correlation between the Variables

The descriptive statistical results of this paper are shown in

Table 2, and the Spearman analysis results are shown in

Table 3. To ensure the validity of the regression model, the correlations between all of them were examined to ascertain whether there was severe multicollinearity. This paper will use variance expression factor analysis to verify whether there is multicollinearity in the model of the variables. Generally speaking, if the VIF value is greater than 10, there may be multicollinearity. Combining the results of the Spearman and VIF tests, multicollinearity is not the concern of this paper.

To prevent the “false regression” phenomenon in the empirical analysis and to ensure the accuracy of the regression results, the panel data unit root test method, namely the LLC test and IPS test, were used to perform the unit root test on the sample. It can be seen from

Table 4 that all of the variables passed the unit root test and that there is no unit root presence and that the variables are quite stable.

3.4. Estimation Approach

3.4.1. The Model of the Effects of FID on the R&D Resource Acquisition

To examine the effects of the FID on the R&D resource acquisition, a panel regression model was defined as follows:

In this model, we list the log of dependent variables, Sf, for regression. A serves as the control variable, containing the human resource level (HR), the innovation intensity (IPP), the trade openness (Open), the economic distance (ED), and the market size (Size).

3.4.2. The Model of the Moderating Effects of FID

In an attempt to verify the influence of the

FID on the relationship between OFDI’s R&D resource and innovation performance, we first constructed a panel regression model to test the effect of OFDI R&D resource on innovation performance using the

FID as the moderating variable. If the coefficient of the interaction term is significant, there is a moderating effect. Conversely, if the interaction term is insignificant, there is no moderating effect. The model was defined as follows:

In this model, we list the log of dependent variables, IP, for regression. is the coefficient of the mediating effect. A serves as the control variable, containing the human resource level (HR), the innovation intensity (IPP), the trade openness (Open), the economic distance (ED), and the market size (Size).

To verify whether the

FID moderating effect in the hypothesis is nonlinear, the threshold regression model is further constructed in this paper. We introduce the

FID as a threshold variable conforming to the OFDI R&D resource and the innovation output model and further analyze its moderating effect. Based on the research of Hansen [

36] and referring to Li and Liu [

16] regarding the analysis method for determining the technology spillover threshold regression, this paper constructs a regression model to investigate the

FID threshold effect. First, the dummy variable D is set as follows:

D is an indicative function, and the

FID is a threshold variable.

m is the threshold value discussed in this paper. Through the above processing, the model is transformed into a piecewise function for the OFDI technology overflow coefficient β.

When the threshold variable is lower than the threshold m, the technology spillover coefficient of OFDI R&D resource stands as β5; when the threshold variable is higher than the threshold m, the technology spillover coefficient of OFDI becomes β6.

After constructing the threshold regression model, we need to determine the threshold value m. Pursuant to the panel data threshold regression theory proposed by Chan (1993), when a threshold value is given, other parameters can be estimated, and the residual sum of squares of the model can be obtained. The smaller the regression sum of residual squares, the closer the segmentation point m is to the threshold value. In this context, this paper sorts the samples in light of the threshold variables, continuously gives possible threshold values, observes the changes in the residual sum of squares, and plots the residual sum of squares corresponding to different threshold values into an image, and the threshold value corresponding to the minimum value position is taken. This is the threshold of possible technology spillover effects. Aiming at the possible threshold value, this paper will also test whether the corresponding β5 and β6 are significantly different.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Regression Analyses of the Effevts of FID on the OFDI R&D Resource Acquisition

We will discuss the impact of the FID from the perspective of the acquisition of OFDI R&D resources. Since this paper uses a multiple regression model of panel data, it is necessary to determine whether to use fixed or random effects regression using the Hausmann test. The results of the Hausmann test shows that the

p value is 0.000 and that fixed effects should be used. The relevant results are shown in

Table 5.

Model 1 is an empty model that includes the OFDI R&D resource and control variables. The empirical test results indicate that all of the control variables are positive for the OFDI R&D resource, which is consistent with the expected hypothesis. Model 2 lists the result obtained by introducing the FID. The elasticity of the FID and OFDI R&D resource is −0.991. It can be seen that the FID has a significant negative effect on the OFDI R&D resource. The larger the FID between the home and host countries, the weaker the absorptive capacity of the OFDI R&D resource. Consequently, this result proves Hypothesis 1. This result shows that the outsider disadvantage theory has dominant explanatory power between the FID and OFDI R&D resource acquisition. When the FID is large, MNEs have to spend money to adapt to the institutional environment of the host country and to gain legitimacy, while the communication gap due to institutional differences increases the difficulty of OFDI R&D resource acquisition.

In the pursuit of clarifying the path and reason of the impact, we will also explore the impacts incurred by each sub-dimension, as the FID covers six sub-dimensions. The results are presented in the

Appendix A. According to the results, we found that the distance between government effectiveness, political stability, rule of law, and regulatory quality have a significant negative impact on the OFDI R&D resource that outperforms the positive impact created by the distance between the control of corruption and political democracy.

4.2. Regression Analyses of the Moderating Effevts of FID

The regression results of the moderating effect of the FID on the relationship between R&D resource and innovation performance are displayed in

Table 6. Model 3 is the null model and shows the relationship between the control and dependent variables. Model 4 is a model that introduces the OFDI R&D resource as the dependent variable, which tests whether there is a knowledge spillover effect in the sample. According to the regression results, the OFDI R&D resource can significantly and positively affect innovation performance, and the elasticity of the two is 0.201; the coefficient of the log of OFDI R&D resource is the efficiency of the OFDI R&D resource on innovation performance. This suggests that China has a significant positive knowledge spillover effect.

Model 5 is a moderating model that introduces moderating variables. In Model 5, the regression coefficient of the interaction term of the OFDI R&D resource and the FID is −0.184 and reaches significance at the 5% level; this shows that the FID has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between the OFDI R&D resource and the innovation performance. The larger the FID, the lower the impact of the OFDI R&D resource on the innovation performance. Hypothesis 2 is confirmed. This result illustrates that the FID increases the difficulty of translating the results as the MNEs transform the acquired OFDI R&D resource into their own innovation capabilities. The larger the FID, the greater the probability that the management experience and knowledge and technology absorbed from the host country will conflict with the technological and management environment of the home country, resulting in absorption and transformation difficulties and low utilization.

To verify whether the moderating effect of the FID is nonlinear,

Table 7 shows the threshold regression results.

In a bid to verify whether the threshold effect exists, the full sample in this paper was set up with 200 grid search points and 300 self-sampling replications, based on which the test results imply that the original hypothesis is rejected at the significance level of 5% and that there is a single FID threshold that is significant, indicating that the FID is a non-linear factor affecting the relationship between the OFDI R&D resource and innovation performance. When the FID is below 8.841, the elasticity between the innovation performance and the OFDI R&D resource is 0.238. When the FID is over the threshold, 8.841, the elasticity between the innovation performance and the OFDI R&D resource is 0.111. Both elasticity and significance decreased, which infers that a shorter FID makes it less difficult for the MNEs to adapt to the institutional environment of host countries. Furthermore, when the FID is too large, the MNES will be confronted with difficulties in accepting and utilizing the advanced technology of the host country and difficulties in absorbing technology spillover through the demonstration effect and the imitation effect.

The results in

Table 7 demonstrate the nonlinear characteristic of the moderating effect of the FID. As the FID increases, the effect of the positive moderating effect of the FID that is explained in the institutional arbitrage theory begins to appear, offsetting the negative moderating effect to some extent, making the overall regulating effect of the FID take on a nonlinear form, and proving Hypothesis 3.

According to the thresholds value calculated in this paper, there are 12 countries in the 2017 sample that lie below the threshold: Turkey, Mexico, Hungary, Greece, Italy, South Korea, Latvia, the United States, Chile, Spain, the Czech Republic, and Poland, 5 of which are developed countries and 7 of which are developing countries. Additionally, there are 16 countries above the threshold: France, Lithuania, Portugal, Estonia, Japan, Singapore, Britain, Canada, Ireland, Germany, Denmark, Finland, The Netherlands, Switzerland, Norway, and New Zealand, among which, 13 are developed countries and 3 are developing countries.

In order to explore the FID threshold effect more deeply and specifically, this paper substitutes each of the six sub-dimensions of the FID into the model as a threshold variable, and the results are listed in

Table 8. According to the regression results, only government effectiveness distance and the political democracy distance have a significant threshold effect, so the threshold effect of the FID may originate from the government effectiveness distance and the political democracy distance. This conclusion needs to be further verified.

4.3. Robustness Test

To ensure the robustness of the empirical results, this section replaces the FID variable and adopts the Heritage Foundation’s “economic freedom” indicator, as described in Estrin [

37]. The “economic freedom” indicator consists of ten sub-indicators, including trade freedom, investment freedom, and financial freedom, to measure the degree of government intervention in the economy, each of which is rated on a scale of 0–100 and is deemed by Estrin to be a reasonable proxy for the three-pillar FID theory. In this paper, the absolute value of the difference of “economic freedom” between China and each host country is used as a proxy for the FID in the model of the relationship between the FID and OFDI R&D resource and the FID model on the relationship between OFDI R&D resource and innovation performance separately for robustness testing, and the results are presented in

Table 9 and

Table 10.

Per the test results, the regression results are basically consistent with the above. On the one hand, the FID is detrimental to the OFDI R&D resource stock. On the other hand, the FID also presents a threshold effect. In other words, in case the FID is higher than the threshold value, the coefficient of the OFDI R&D resources would drop remarkably.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In recent years, affected by the COVID-19 epidemic and trade protectionism, the OFDI from developing countries, especially OFDI with the main purpose of knowledge seeking, has been seriously affected. OFDI in developed countries has become an important means for developing countries to achieve technological progress, so how to improve the knowledge spillover effect resulting from OFDI plays a great role in solving the sustainable development problems of developing countries. This study focuses on the efficiency of emerging country MNEs to improve their innovation capabilities by seeking and transferring knowledge from developed countries. Although it has been proven that OFDI in developed countries has already become a significant approach through which emerging country MNEs seek knowledge, little is known about the factors affecting the efficiency of MNEs from emerging countries to improve their innovation capabilities using this approach. Our study contributes to this research area. We argued that the FID can affect the innovation performance of OFDI firms in two ways: by means of OFDI R&D resource acquisition and the innovation performance of OFDI R&D resource. According to the outsider disadvantage theory, the FID will have a negative effect on OFDI R&D resource acquisition and will have a negative moderating effect on the relationship between OFDI R&D resource and innovation performance. However, due to the institutional arbitrage theory, the moderating effect of the FID will be weakened for emerging countries when the FID is over the threshold value.

5.1. Main Findings

Using country-level panel data from 28 major OFID destinations in China over the period from 2003 to 2017, we found robust evidence to prove the impact of the FID on the innovation performance of Chinese OFDI companies from the perspectives of OFDI R&D resource acquisition and the relationship between OFDI R&D resource and innovation performance. The following main conclusions could be drawn:

First, the FID has a significant negative effect on the acquisition of OFDI R&D resources; that is, the greater the FID between China and the host country, the more difficult it is to obtain OFDI R&D resources.

Second, this paper also found that the FID has a significant negative moderating effect on the relationship between OFDI R&D resources and innovation performance. Compared to the results before the introduction of the FID, the positive relationship between the OFDI R&D resources and innovation performance is significantly weakened. When the FID is narrow, it is less difficult for Chinese companies to adapt to the host country’s institutional environment. On the contrary, if the FID is too large, it is hard for Chinese MNEs to accept the advanced technologies from host countries.

Thirdly, the FID has a significant threshold effect on the effect of the OFDI R&D resources and innovation performance. This result illustrates that the moderating effect of the FID is nonlinear and that the moderating effect is negative and significant when the FID is less than the threshold, and becomes smaller in absolute value and significance when it is higher than the threshold.

Finally, the threshold effect of the FID comes from the government effectiveness distance and the political democracy distance, both of which also have a significant threshold effect on the relationship between the OFDI R&D resources and innovation performance.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

For scholars who are interested in the reverse technology spillover effect of OFDI, our work creates new insights. Most of the literature on influence factor of the reverse technology spillover effect focuses on the country’s quality and economic and technological gaps. However, some invisible factors, such as institution, have not been fully discussed. Our work draws on the discussion of Ran et al. and Yi et al. on the relationship between institutional quality and reverse technology spillover [

7,

24]. Their views provide the basis for the theory of institutional arbitrage seen in this paper. Our work develops the point of Lin et al. [

23] that the FID negatively moderates the relevance between innovation capability and the OFDI reverse technology spillover effect at the empirical level. Our results demonstrate that the negative moderating effect of the FID is nonlinear and takes the form of a threshold effect. Compared to the existing literature, the contribution of this paper is to decompose the reverse technology spillover process into OFDI R&D resource acquisition and the relationship between OFDI R&D resource and innovation performance to explain the conclusions under the theory of outsider disadvantages and institutional arbitrage.

5.3. Political Implications

Our findings have two key implications for practices related to knowledge seeking through OFDI. First, the MNEs from emerging markets that are interested in knowledge acquisition should pay more attention to the FID when choosing the host countries to be used as investment targets. Our studies suggest that they should choose countries within the FID threshold as investment targets. Second, among the six dimensions covered by the FID, the MNEs from existing markets should focus on the government effectiveness distance and the political democracy distance, both of which have a more significant threshold effect than other dimensions.

5.4. Suggested Future Extensions

Future studies can extend our research in multiple ways. First, future research could explore the specific impact of the FID on OFDI decisions of MNEs at the firm level. The existing innovation literature suggests the importance of company-level factors [

38,

39]. This paper mainly explores the relationship between the FID and innovation in OFDI MNEs at the country level, but firm-level data can further refine the influence mechanism by sorting out changes in firm behavior, such as R&D investment. Second, we encourage future studies to adopt more detailed innovation output variables to capture the technological capabilities of MNEs, such as types of patents, the number of new products, and the sales of new products. Thirdly, future research can clarify the factors influencing innovation through mediating variables, and the existing literature has sorted out several possible paths of influence, such as local supply chains, as well as collaboration with local technical teams.