1. Introduction

Population aging is an inevitable trend in the population age structure when the social economy develops to a certain stage. According to the proportional distribution of the elderly over 65 years old within the total population, the World Health Organization (WHO) classifies the aging society into three levels, namely the aging society (7%), the aged society (14%), and the super-aged society (20%) [

1]. At the same time, in 2007, the WHO issued a programmatic document, Global age-friendly cities: A guide, which lists the basic characteristics of elderly-friendly cities according to eight aspects: outdoor space and architecture, transportation, housing, social participation, respect and tolerance, citizen participation and employment, information exchange, and community support and health services [

2]. In this context, according to China’s seventh national population census, in 2020, there were 190 million people over the age of 65, accounting for 13.5% of the total population, and China is currently in the later stage of an ‘aging society’. From 2010 to 2020, the proportion of the population aged 60 and above increased by 5.44%, and the population aged 65 and above increased by 4.63% [

3]. In August 2016, China developed and adopted the Outline of the Healthy China 2030 Plan [

4]. In 2019, two important official documents from China’s central government, Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Implementing Healthy China Action and Implementation and Assessment Plan of Healthy China Action, were officially issued. Meanwhile, the institute of the Healthy China Action Promotion Committee was also established in the same year [

5,

6]. Therefore, as the core strategy, all the policies that belong to the theme of ‘Healthy China’ have aimed to respond to the aging society, and related policies have been continuously implemented since then.

Under the guidance of China’s central government, the regeneration of the elderly-friendly built environment has recently become an important and necessary issue at the sub-national level, especially at the urban level. Based on these policies, spatial objects in the elderly-friendly built environment include privately owned houses for the elderly, other privately owned commercial facilities in the city, communities shared by multi-property owners, and public spaces and public service facilities shared by all citizens. Because of the differences in the types of public and private property rights, the responsibility of local governments focuses more on public spaces and public service facilities. Among the various types of public spaces, street space is undoubtedly the most commonly and frequently used type in the city, because the elderly use street space whenever they travel [

7]. In addition to playing a basic role in citizens’ ability to commute, the street space itself is also a place where various activities, such as social interaction, leisure activities, exercise, recreation, and visiting of the elderly, take place. Thus, due to the importance of street space in the daily activities of the elderly, and the operability of urban aging-friendly renovation under the leadership of the government, this study focuses on the elderly’s subjective perception of the street form.

The street form is defined as a three-dimensional space formed by the intersection of the sidewalk, the driveway, and the building interface on both sides of the road, including road pavements, street furniture, transportation facilities, the green landscape, building facades, and other spatial elements [

8,

9]. The street form carries a traffic function and a life function [

10]. The subjective perception of the street form among the elderly involves the psychological information collection and processing of the various spatial elements themselves in the built environment, as well as the interaction between these elements. Research within human–environment relations has shown that subjective perceptions reflect the degree to which the physical built environment matches the behavioral habits of the elderly [

11]. The factors that affect psychological satisfaction include personal characteristics, personal preferences, and environmental characteristics [

12]. With the rapid development of China’s urban economy and the improvement in urban infrastructure, the travel needs of the elderly have increased, and the needs for street space are no longer limited to safety and convenience. The construction and regeneration of street space should achieve more diverse goals on the psychological level, such as improving local identity and inclusiveness. Given that related age-friendly research mostly concentrates on the aspects of housing, community, infrastructure, and public service facilities, there are fewer related studies to investigate the subjective perception at the street level. In addition, very little research has examined the relationship between the elderly group’s perception and the detailed street form. Thus, our study focuses specifically on this type of public space, and aims to offer some suggestions for the improvement of their design strategies based on the elderly’s perceptions.

This study aims to examine the diverse needs of the aging population for street space by focusing on hierarchically structured data. Accordingly, based on first-hand surveys, we explore the different priority sequences of needs, coming from different ages, genders, living conditions, and education levels. In particular, this study, by using a series of spatial indicators to describe street form, further examines the relationship between the aging population’s subjective perception (satisfaction of needs found in the former survey) and the physical urban form. Our study is important because the government-led public space regeneration under aging-friendly policy occurs not only in China, but globally, especially in developed cities with aging societies [

13,

14,

15]. However, regarding current urban regeneration practices, the construction behavior does not consider the value appeal of different stakeholders. In particular, the related planning and design does not take the psychological feelings of the elderly about the physical environment into account, resulting in a large amount of financial input and social discontent. Therefore, this paper can offer significant insights into the subjective perceptions of the aging population in developed cities regarding the daily use of the street. Furthermore, our study is also conducive to detailed design strategies’ formulation and the enhancement of aging people’s satisfaction with future street space regeneration. Moreover, our findings would promote a wider dialogue on the social sustainability of the specific social group in the attainment of a desirable city form.

This study contributes to existing knowledge in the following ways. First, it focuses on changes in aging people’s priorities and needs regarding developed cities’ streets, which is something that relatively few studies have previously explored. This study focuses on the social needs of the elderly beyond their basic traffic needs, as well as the differences and commonalities among elderly groups with different characteristics. Although the regeneration of the aging-friendly environment has been a prosperous topic in China, existing research on aging people’s spatial needs mainly focuses on traffic safety or convenience, and the layout of old-age service facilities in cities. The analysis of needs could provide significant clues about how to understand and grasp the perceived focus of this group in more detail. Second, the study employs the semantic differential method, which can help us to better understand the detailed perception of the urban form [

16]. Moreover, econometric method analysis also reveals the overall perception trend of the elderly for the street form at the macro-level for the first time. At the micro-level, we focus on individual psychological perceptions and geographical narration through interviews. Thus, the integration of different research methods is helpful to break the barriers between pure psychological cognition research and space design research.

2. Literature Review

This section discusses critical related works on streets from a historic perspective, to summarize the focuses of existing studies in different periods. Since the end of the 20th century, numerous studies have focused on street form’s effect on human beings, and have explored the design principles of street space. Streets represent the vitality of a city. A vibrant street does not only have a strong transportation capacity, but allows the integration of multiple functions. This emphasizes that the street space design should be people-oriented, and pay more attention to the needs of street users [

17]. Based on the analysis of excellent streets around the world, some scholars proposed that successful streets can contribute to good neighborhood relations and promote the establishment of safe and comfortable environments for residents [

18]. In addition, some qualitative evidence also supports the related issues, and increasing studies have begun to focus on the impact of specific spatial characteristics on residents [

19,

20,

21,

22].

At the beginning of this century, many scholars studied the behavioral characteristics of the elderly in cities and streets, based on behavioral geography, spatio-temporal geography, social investigation, and other methods [

23,

24,

25]. Vojnovic has shown that accessibility, comfort, safety, and entertainment in streets are more likely to attract people to non-motorized travel [

26]. Purciel’s research shows that if a street has a pleasant scale, a sense of place, a high degree of street recognition, high visibility, and a rich landscape configuration, it will attract people to travel actively [

27]. Millington believed that the factors contributing to pedestrianism include street aesthetics, traffic safety, mixed land use, building density, pavement, street connectivity, service facilities, proximity to sports venues, and parks and greenery [

28]. Among the many influencing factors, permeability is the main focus. Tan proposed that a street with high permeability means a high density, good connectivity, and a flat structure based on the permeability angle of the street space, which can bring more interest and choice to residents and stimulate the vitality of the city [

29]. The permeable street form has five main basic characteristics: high layout density, good connectivity, many entrances and exits, a non-hierarchical nature, and a pleasant enclosure ratio [

30]. Ewing selected eight perceptual characteristics that may affect the walking environment through a literature review, namely image, enclosure, human scale, transparency, complexity, recognizability, relevance, and coherence, and proposed a quantification method for the first five characteristics [

31]. Sugiyama found that people living in a supportive environment tend to walk, and that influencing factors include the neighborhood space, the quality and openness of green space, comfortable environmental factors, and better health conditions, through a questionnaire survey of the elderly’s outdoor activities [

32]. Neighborhood environments can promote the health of the elderly in two ways: one is to make them more active, and the other is to provide them with places to socialize with others and enjoy nature.

Recently, under the concept of the healthy city, there have been numerous studies on the impact of street form on pedestrian activities. Winters et al. recorded the daily activity trajectories of the elderly based on the question of where and how to go, and found that the elderly in the accessibility community engage in a higher frequency of walking activities, more intensive social interactions, and more walking and physical exercise; the modes of transportation during these activities are more likely to be walking or public transportation [

33]. Similarly, Elsawahli pointed out that permeability, accessibility, and walkability are key factors in age-friendly communities [

34]. Burton et al. explored the influence of the outdoor environment on the perceptions of the elderly, and they introduced the concept of ‘living street’ to propose that an elderly-friendly living street should follow the principles of familiarity, legibility, uniqueness, accessibility, comfort, and safety [

35], Sun et al., taking Hong Kong as an empirical case, put forward a similar view [

36]. By establishing a measurement system for the quality of street walking activities, Xu and Shi analyzed the relationship between quality and the built environment, and found that continuous storefronts, dense road networks, greenery, seating facilities, high-quality building facades, historical buildings, and a pleasant scale are of great significance to the improvement of the quality of walking activities [

37]. In addition, studies have shown that street space has a healing effect on users, which is related to the street’s green vision rate and street interface, and increasing the street’s green vision rate can improve the healing effect [

38]. Han et al. analyzed the impact of street attractiveness on the feasibility of activities among the elderly, and found that in terms of street life, the density of street facilities can promote leisure and social activities; in terms of street aesthetics, street greenery can positively regulate their willingness to perform daily activities, and the interface continuity of the road helps to improve the frequency of leisure social activities [

39]. Tan et al. showed that the intervention degree of the community walking environment can effectively express the health intervention performance of the walking environment regarding people’s physical activity; a community walking environment with a dense road network, convenient public transportation, excellent service facilities, and high environmental quality has a higher degree of intervention for physical activity, which helps to improve the health of people [

40].

Therefore, overall, various factors of street form can exert different effects on people, and the influential degree can be measured. However, as for the aging group, which detailed factors and which combinations of factors are determinants is still unclear. The internal difference in the aging group also does not obtain enough attention. In addition, in existing studies, the effects coming from street form, maintenance, management, and the land function layout outside the street, etc., usually are not well distinguished. Thus, in order to examine the spatial determinants related to elderly-friendly street design, this paper tries to build linear relationships between the spatial factors and perceptions of aging people by employing both space survey and social survey methods.

3. Methodology

3.1. Case Study

Shanghai is the most economically developed city in China, with a GDP of approximately USD 679.1 billion in 2021 [

41]. Meanwhile, Shanghai is one of the most serious aging cities in China. It entered an aging society in 1979 [

42]. At the end of 2019, the proportion of the elderly aged 65 and above in the household registration population reached 23.0%, and the proportion of the elderly population over 60 years old was as high as 34.4% [

43], which means that, on average, one in every three members of the registered population is over 60 years old, and one in every five in the registered population is over 65 years old.

In addition, Shanghai is also the leading city in China in the construction of elderly-friendly spaces. Since 2009, China’s central government has selected a number of cities with a serious aging phenomenon in the eastern region (the eastern coastal and northeast industrial bases), to carry out the experimental policy of building aging-friendly cities. The national policy encourages local governments to enhance the sustainable ability of cities to cope with the aging problem by improving the built environment [

44]. Shanghai was one of them. Furthermore, in recent years, Shanghai has successively issued local policies to deal with the aging society, such as the Regulations on the Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly in Shanghai and Guidelines for the Construction of Shanghai Elderly Friendly Cities (Trial), which specifically declared the requirements for the walking environment and traffic system to ensure the safety of the elderly, and the requirements for the improvement of the orientation and safety performance of the road system [

45,

46]. Thus, Shanghai constitutes a typical example of an aging society, with which we can explore the elderly’s perceptions of streets.

3.2. Study Design

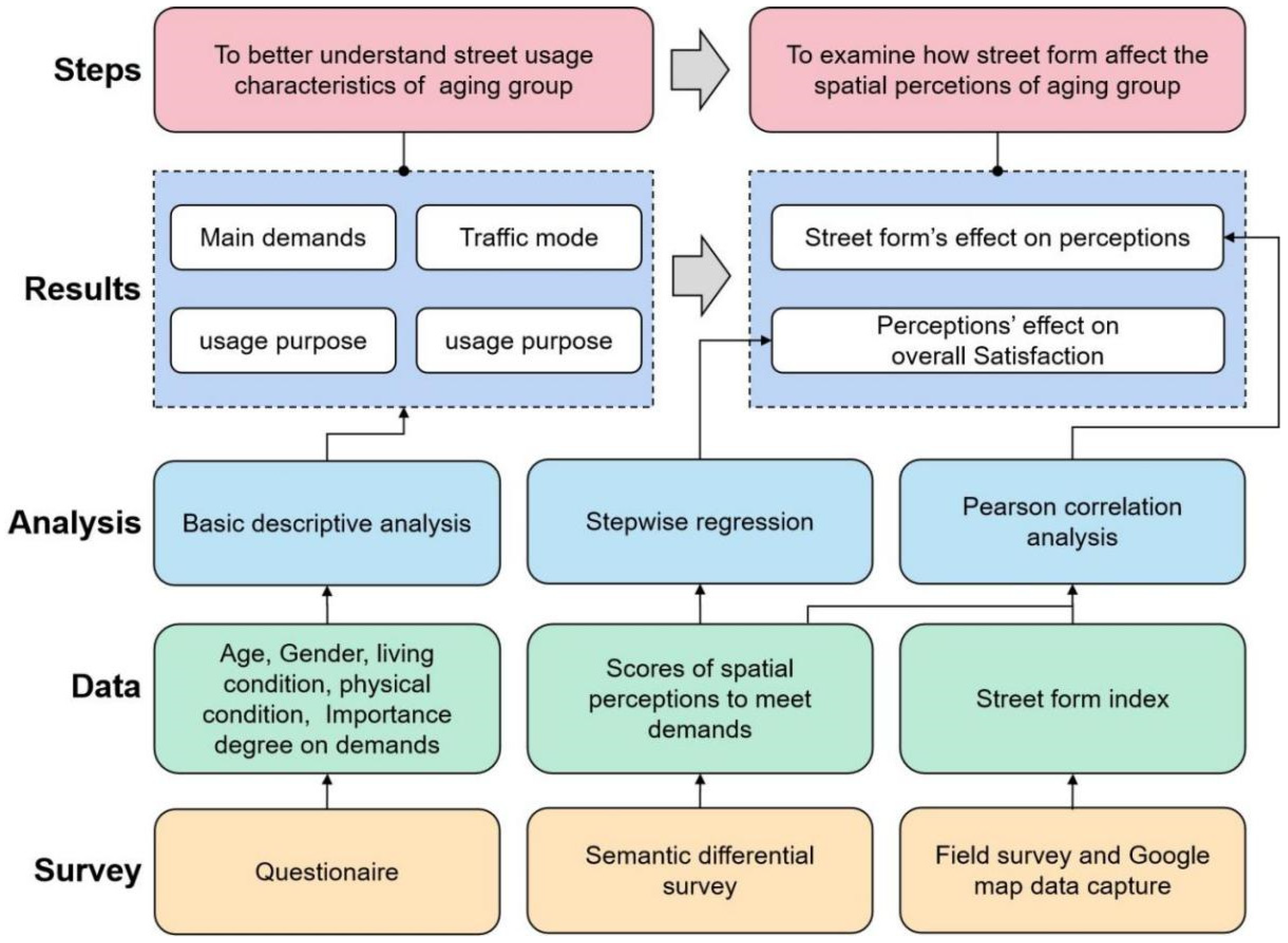

This study consists of two steps, as shown in

Figure 1. The first stage is the research of the Shanghai aging population’s needs and usage characteristics with street space. Through a questionnaire survey, preliminary statistics of the current travel habits and travel experiences of Shanghai’s aging population are explored. Then, the needs system of the aging population is further refined, and the priority of the needs is ranked.

In the second stage, different types of streets in Shanghai are selected as empirical objects. Firstly, groups of adjectives that reflect the subjective perceptions of the aging population are identified via the semantic differentiation method. Moreover, stepwise regression analysis is employed to observe the variables that affect the overall satisfaction towards the streets. Then, the physical space indexes reflecting the built environment are selected, and the relationship between the physical space indexes and the subjective perception of the elderly is tested by Pearson correlation analysis. Finally, based on the above empirical analysis, spatial development and planning strategies are put forward to promote the social welfare of the aging population.

3.3. Social Survey

Our social survey is divided into two parts: the street usage characteristics and subjective perceptions of aging people. The two-part investigation is a gradual and in-depth process. The former focuses on the superficial behavioral habits of the elderly, while the latter focuses on the psychological causes.

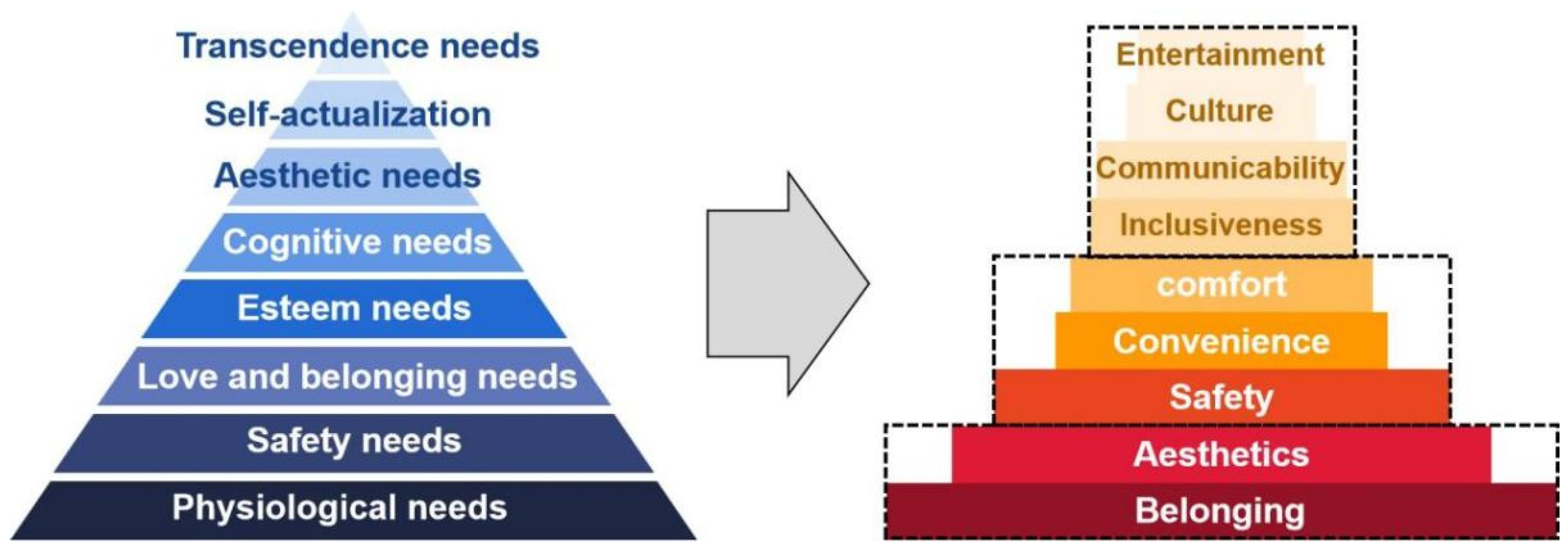

First, a questionnaire is used to obtain basic information about aging people. In order to quantify the basic information, health level, and needs for different street qualities among the elderly, this paper compares the preferences of different age groups for various street elements through cross-analysis. The contents of the questionnaire include the basic personal information of the elderly (such as age, gender, living condition, and physical condition), and the investigation of the elderly’s needs for street quality. We summarize the primary indexes of the physiological, psychological, and behavioral needs of the elderly for street space as ’safety, convenience, comfort, communicability, aesthetics, attribution, culture, entertainment, and inclusiveness’. The respondents are required to score 0 to 4 for each index factor (higher score indicating greater importance) so as to quantify and refine the needs of the elderly for street space.

Second, to quantify the elderly’s diverse perceptions of streets, we employ a semantic differential survey, which was developed by psychologist Osgood in 1957 [

47]. In the method, aiming at a given concrete or abstract research object, several opposite adjectives can be paired as a scale, and different magnitudes can then be set to quantitatively analyze and describe the research object [

48]. The semantic differential method generally selects a number of adjectives related to the described object as evaluation factors, and each pair of antonyms can be used as the two extremes of an evaluation of street perception [

49]. Based on the questionnaire results, this study selects 22 pairs of antonyms as factors, under 9 main needs, to evaluate street design, as shown in

Table 1. In order to make the description more accurate, an evaluation scale with 7 magnitudes (1 point each magnitude) is selected, in which the median is set as 0 points and the positive and negative values are 3 magnitudes, respectively. Positive values represent positive feedback from the elderly, while negative values mean negative feedback.

3.4. Statistic Analysis

This paper adopts two statistical analysis methods. The first is stepwise regression. By capturing the hierarchical structure underlying the elderly’s perceptions, as listed in

Table 1, this method helps to explore the determinants of spatial perception and their effect on overall satisfaction. The basic idea of stepwise regression analysis is to select the most important variable from many variables and establish the prediction or interpretation model of regression analysis, and finally to establish an optimal multiple linear regression equation. Its basic process includes the following: the independent variables are introduced one by one, on the condition that the sum of partial regression squares is significant after being tested, and after each new independent variable is introduced, the old independent variables should be tested one by one, and the independent variables with insignificant partial regression squares should be eliminated until neither new variables are introduced nor old variables are deleted. The basic multivariate regression model is as follows:

where

S, the dependent variable, refers to the score of the elderly’s overall satisfaction with the street.

is a set of variables (evaluation factors listed in

Table 1).

is the vector of regression coefficients used for the estimations.

is an error term. The calculation process begins with establishing univariate regression models for different independent variables and dependent variables, respectively, and calculating the value of the F-test statistic,

…

. Then, we choose the maximum value:

For a given level of significance α, we calculate the critical value as . If , then we introduce into the regression model, and can be selected as the variable index set. The next step of the calculation is to build the binary regression models. However, one of the variables has been determined in the former calculation, and the same test process will be repeated to determine another variable. We keep introducing new independent variables, and thus we can obtain a relatively ideal multiple linear regression equation, which represents the spatial perceptions’ quantified effect on satisfaction.

Second, Pearson correlation analysis is selected. This method is used to measure the linear relationship between distance variables. In our study, it helps to further examine the relationship between the subjective perceptions of the elderly and the objective index factors of street form. In the process of analysis, the research focuses on the variables determined in the previous stepwise regression model construction. Using the Pearson method, we can test the degree of influence based on the street form index on these important variables, which can provide a reference for urban planners to improve the current street’s level of aging friendliness. Designers can also respond to the elderly’s specific perceived emotions by controlling the specific spatial form.

3.5. Data Collection

The data are derived from two sets of social surveys, and fieldwork in Shanghai was conducted in 2020. Spatial data are captured by Google Maps, as a supplement to the field surveys. The design of the survey questions is based on interviews conducted in Shanghai in 2019. We derived the questions from the existing studies, but we develop them by considering more detailed spatial needs and quantifiable perceptions. Because of the different purposes of these two social surveys, the scope of the selected survey objects is also different. For the first, the basic object is the administrative district, while, for the second, it is a specific street.

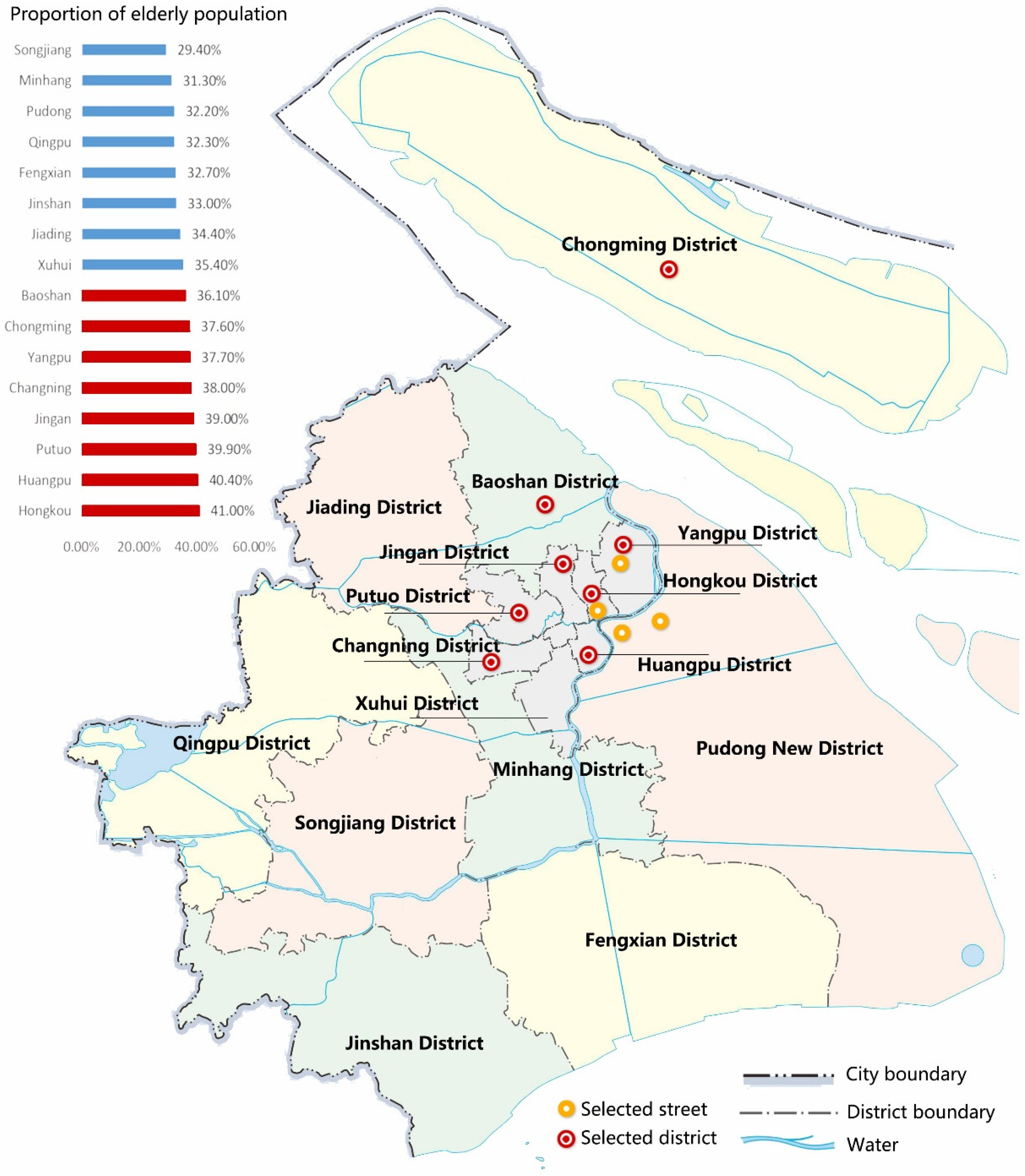

In the first step, eight of Shanghai’s 16 administrative districts are selected because they have the highest proportion of the elderly population. It can be seen clearly in

Figure 2 that most selected districts are located in the traditional central area of the city, which accords with the analysis of the spatial distribution characteristics of Shanghai’s aging population in the existing research [

50]. Fifty questionnaires were randomly distributed in each district (total of 400 questionnaires), while 381 questionnaires were collected, with an effective rate of 95.3%. In the second step of the study, four streets with different characteristics in Shanghai were selected as a research sample for the distribution of semantic differential questionnaires. Considering the elderly’s habit of going out, the questionnaires were distributed on weekdays and weekends, which were divided into three periods, namely 7–10 am, 10–2 pm, and 2–5 pm. Twenty questionnaires were distributed in each period of a distribution day, totaling 120 questionnaires per street and 480 questionnaires in total for four streets. The validity of the questionnaires was mainly determined by whether the elderly could accurately understand the logic of the SD questionnaire. Finally, 471 valid questionnaires were collected, with an effective rate of 98.1%.

In addition, in order to describe the objective form of street space, this study selects 11 index factors, as shown in

Table 2, that might affect the elderly’s feelings towards the street space from the aspects of street scale, interface, greenery, rest space, and barrier-free facilities. Street-scale indicators are very important for the elderly to evaluate the safety, convenience, comfort, and belonging of streets. Generally, the indicators used to describe street scale include the street length, total street width, vehicle lanes’ width, pedestrian sidewalk width, and ratio of width to height. We select one index of green coverage rate for street greening [

51]. The street-facing interface is the vertical interface of street space and also an important part of the street. Its color, scale, continuity, perspective, etc., all affect the elderly’s usage and experience, and have an important impact on the vitality and characteristics of the street. Therefore, the continuity and underlying transparency of the street-facing interface are selected as two indicators [

52]. Through the pre-research, we know that street parking is essential to the elderly’s perceptions of street satisfaction, so we select two indicators, the density of squares along the street and the density of rest facilities, to represent the parking space. As for barrier-free facilities, we use the setting rate of barrier-free facilities to calculate the proportion of the number of barrier-free facilities at various intersections, entrances and exits, crosswalks, and blind roads, so as to reflect the barrier-free popularity of streets.

5. The Spatial Form and Perception of Streets

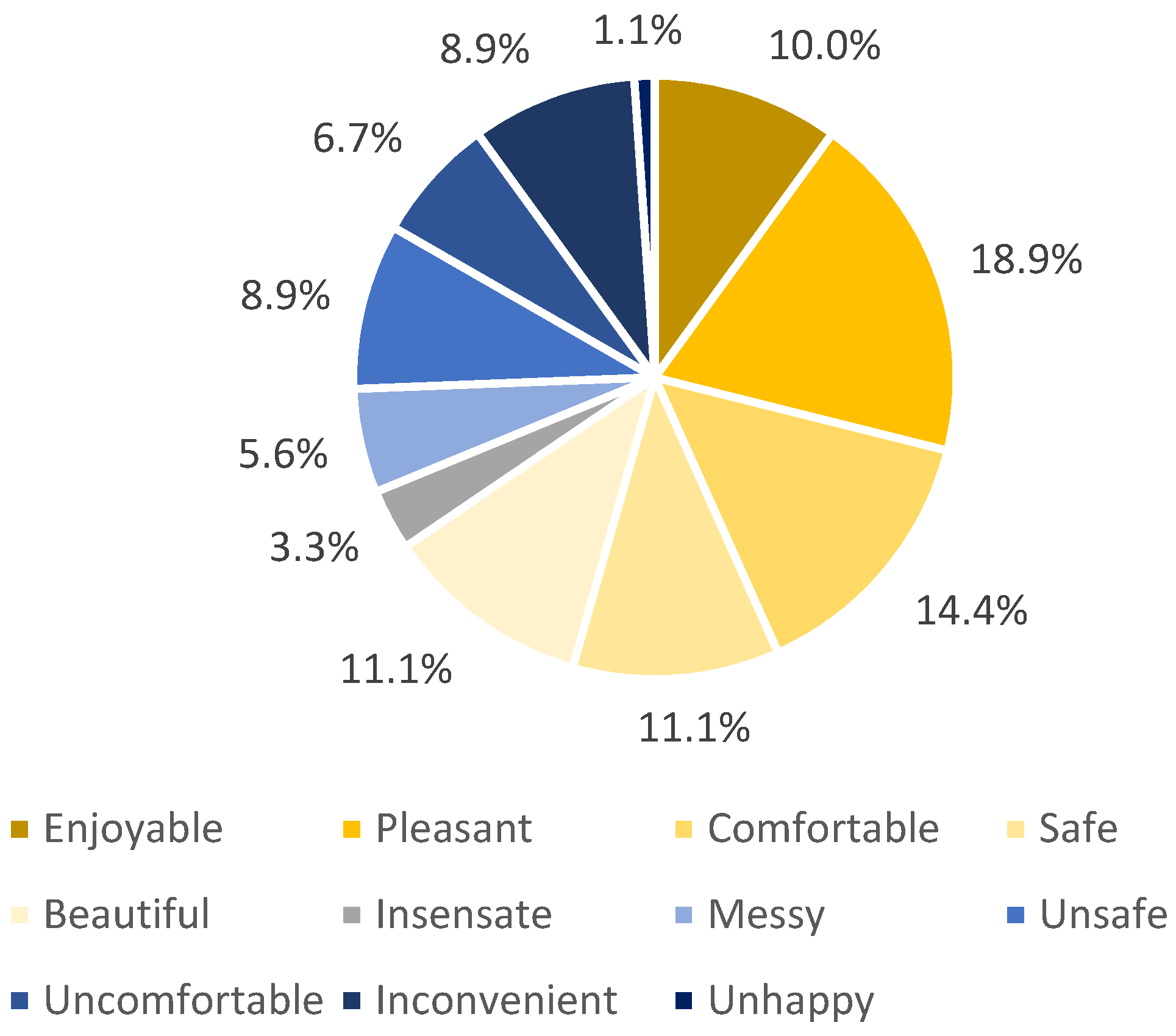

5.1. The Subjective Perception and Overall Satisfaction

In order to explore the relationship between the elderly’s overall satisfaction with the streets and various subjective perceptions, this study employs multiple linear stepwise regression to test the influence of the 22 evaluation factors listed in

Table 1 on the overall satisfaction of the elderly. The study selected four streets in Shanghai and collected their spatial index factors, listed in

Table 2. The samples were Century Avenue, a landscaped street surrounded by modern high-rise commercial buildings; Hailun Street, a historic street surrounded by traditional historic buildings and residential buildings; University Street, a commercial street surrounded by small cultural and creative commercial buildings; and Rushan Street, a residential street surrounded by multi-story old residential buildings. As shown in

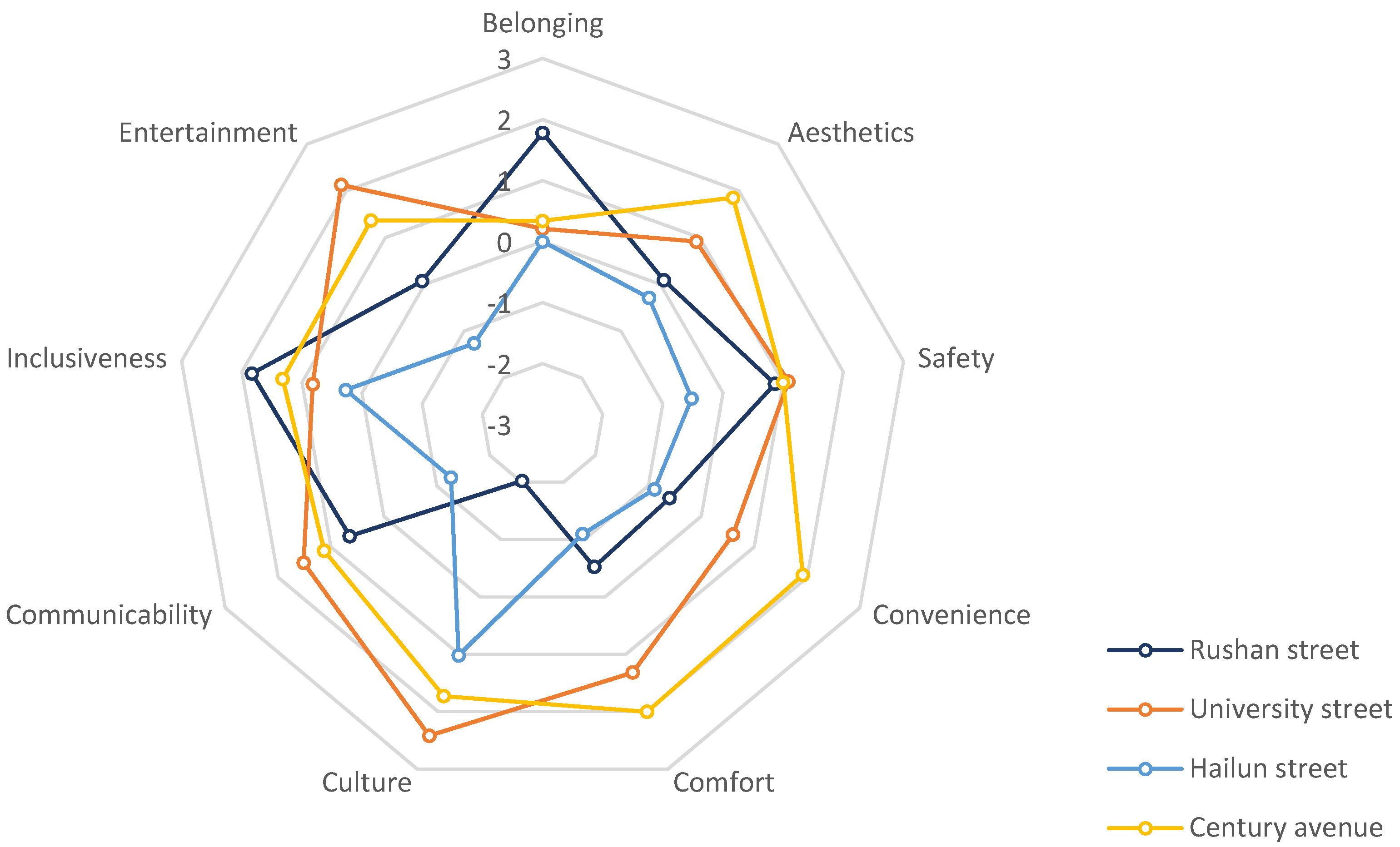

Figure 5, the results of the SD survey showed that the elderly’s subjective perceptions of the four streets differed greatly in the nine types of needs. The scores of University Street and Century Avenue were almost all above 0, and the overall satisfaction with the streets was high. The scores of Hailun Street were mostly below 0, and the overall satisfaction with the street was low. Such results reflect the different characteristics of each street, which is also consistent with the principle and original intention of the initial sample selection.

In order to avoid the effects of multicollinearity, we conduct the VIF test. The results are shown in

Table 3. All values of VIFs are less than 10, and thus the multicollinearity issue is not a challenge for our study. In the multiple linear stepwise regression analysis, five equation models were fitted, and the variables included in the models were as follows: the lighting degree of the street (9. Bright–Dim), the vitality degree (19. Lively–Deserted), the spaciousness of the sidewalk (13. Spacious–Narrow), and the staying ability of the street (18. Willing to stay–Rush by). Hypothesis testing results showed that the F values were 103.713, 67.807, 50.245, 40.001, and 52.744, respectively, and the

p values were all less than 0.001, which indicated that the regression model was statistically significant. Compared with the null model, the inclusion of independent variables was helpful to predict the dependent variables. R

2 and adjusted R

2 represent goodness of fit, and they could be used to estimate the fitting degree of the model to the observed values. From the regression analysis, it can be seen in

Table 3 that with the increase in the number of variables in models 1, 2, 3, and 4, the R

2 and the adjusted R

2 reflected an increasing trend, while model 5 showed a decreasing trend, and the adjusted R

2 of each fitting model was more than 0.5. Therefore, the explanatory degree of the independent variables to the dependent variables was relatively high. Using the above methods, the research concluded that vitality, spatial scale, and street attraction were not only important influencing factors that affected the overall satisfaction of the elderly, but also the key points that should be considered in relevant planning and construction in Shanghai.

5.2. The Subjective Perception and Objective Street Form

The study adopted Pearson correlation analysis to analyze the relationship between the 22 evaluation factors included in the SD survey in

Table 1 and 11 space index factors selected from

Table 2. The closer the Pearson correlation coefficient is to 1, the stronger the positive correlation relationship that exists. Aging people’s perceptions of street aesthetics and convenience are most influenced by the street space form, while perceptions of street comfort and safety are influenced by the street space form, and perceptions of entertainment, culture, inclusiveness, and communicability are relatively less influenced by street form. Therefore, combined with the research results on the appeal level of the elderly in the third part of this paper, we suggest that the regeneration and transformation of street form can meet the most concerned use needs of the vast majority of the elderly. Furthermore, 27 pairs of factors were significantly correlated, as shown in

Table 4, and three main findings were concluded as follows.

First, the interface’s transparency is a very important factor that affects the types of perception. The higher the index of the underlying interface’s transparency, the greater the spatial perception the elderly for the space. This is due to the magnifying effect of the transparent open interface in the line of sight. At the same time, the higher the index, the more willing the elderly are to stay on the street, which also increases their perception of the interest of the street. This is because street-facing interfaces with high transparency are often equipped with more shop glass, which not only attracts the elderly but also increases the vitality on both sides of the street. The transparent interfaces and door heads of shops are another type of street symbol, which, to a certain extent, deepens the memory of the elderly regarding the street. For this reason, the elderly also believe that a street with high transparency is relatively more memorable and more iconic. In addition, the higher the transparency of the street, the better the greenery level of the street according to the elderly. This is because streets with high transparency are normally related to a higher grade and better spatial quality, with relatively more greening plants. The higher the index of ‘continuity of street interface’, the more the elderly feel that the space is closed. The elderly prefer a street with less continuity of interface, and the transparent line of sight can appease their uneasy mood.

Second, in terms of the effect of street scale, the higher the index of the pedestrian sidewalk width, the cleaner the elderly perceive the street to be. Moreover, the more unimpeded the streets are, the more convenient they feel to find a place to rest. Wide sidewalks mean fewer people on the street, which makes people feel orderly. On the other hand, to some extent, it also means a higher level of streets. In other words, more rest facilities may be equipped on both sides of the street, which makes it more convenient for the elderly to rest. These have improved the elderly’s evaluation of the street staying ability. In addition, the smaller the ratio of height to width, the stronger the perception of safety, unblocked vision, and space openness held by the elderly, because a spacious street makes the elderly feel more secure, and a narrow street is often linked with the mixed traffic of people and vehicles. The width of streets also affects wheelchair use and walking, which may produce more uneasy feelings when inconvenience and a sense of congestion occur.

Third, as for public space and facilities, the setting rate of barrier-free facilities certainly has positive effects on the elder’s perception of safety and inclusiveness, but the density of street squares along the street is also a key factor. Higher density means that older people are more willing to stay on the street, because street squares usually provide older people with more rest and social spaces. It also improves elderly’s perceptions of order. In addition, the index of the density of street rest facilities contributes to not only better perceptions of convenience and comfort, but also the perception of the greenery level of the street, which is related to the appearance of rest facilities and greening facilities.

6. Conclusions

The regeneration of street public space is the focus of China’s urban government’s active aging policy. However, the current spatial planning and design practice generally lack evidence-based support. The project focuses on the safety of streets, but ignores the changing needs of the elderly. In China, cities with serious aging are often economically developed. The elderly in these cities use the street public space more frequently, and their needs are more diverse. Therefore, this paper aims to explore the usage characteristics of the aging population, and to reshape the intrinsic cognition of their structure of needs. Furthermore, we hope that, compared with the existing research, we can further explore which street forms affect the elderly’s perceptions of their different needs, and then provide a reference for specific street planning and design.

Our results based on the district-level survey suggest that street space is playing an extremely important role in the elderly’s daily lives. They have various travel purposes, and the frequency of street usage is high. Their needs of streets, surprisingly, differ from the common cognition. The need for a sense of belonging has replaced the position of the basic use need. They expect the streets around their communities to feel familiar, instead of rapidly changing under China’s rapid urbanization process. In addition, with the aging of the population, the aesthetic needs of the streets are more important than the safety needs. This means that retaining the local memory of the street and emphasizing the local characteristics from a visual point of view may be more important than transforming the physical facilities. In the street-level survey, this study found that aging people’s perceptions of their primary needs are highly correlated, meaning that spatial design indeed has the possibility to become an effective way to improve the social welfare of the elderly. We found that higher street vitality, more spacious sidewalks, and more street-staying space had a significant influence on this group’s overall satisfaction. Specific physical spatial indexes, such as street length, total width of street, width of walkable sidewalk, density of rest facilities, density of squares along the street, transparency of underlying interface, etc., were more important to the perceptions of convenience and aesthetics among the aging population. The ratios of height to width, interface continuity, and barrier-free setting rate impact the perception of safety and comfort, and the greenery coverage rate was also an important factor affecting comfort. For the communicative perception, the influencing factors included the walking width, the transparency of the underlying interface along the street, and the density of the squares along the street. The above-mentioned spatial characteristics should be important considerations for street space construction in Shanghai’s elderly-friendly city development.

Regarding theoretical implications, our results indicate that the specific group’s needs for specific types of space have great particularity, and may be against the need hierarchy established by existing research. The sequence of their priority may also reflect a failure to comply with the order of needs from survival to self-actualization. The high-level spiritual need can be the most fundamental need, such as the need for belonging among aging people. This represents the discomfort caused by potential social phenomena such as rapid changes in the surrounding environment and lonely living conditions. Similar conclusions often appear in community-related research, but we find that the street, as a public space frequently used by the elderly, should also respond to these important needs [

56,

57,

58].

Regarding policy implications, this paper suggests that the construction of an elderly-friendly city, especially the elderly-friendly regeneration of street space, which is the most common public space, should start from the particularity of the needs of the elderly with different geographical backgrounds, and understand the usage characteristics and subjective perceptions of local aging groups based on social investigation, so as to promote the personalization of space design strategies. This paper analyzes the subjective perceptions of the aging population towards street space, as well as the spatial elements and corresponding indicators that can improve their satisfaction, based on interviews and questionnaires. Our study can also provide a reference for similar practices in other cities. In recent years, the Chinese government has advocated for the development of a ‘people’s city’, the core of which is to formulate the development strategy of the city to meet the needs of the vast majority of citizens [

59,

60,

61]. The related actions taken are started by ‘urban physical examination’, which mostly consists of big data and social surveys to evaluate the quality of urban construction and development annually, and to guide the formulation and implementation of urban planning. The combination of survey and analysis methods in our study can be integrated with the ‘urban physical examination’ works that have been carried out in all China’s cities by adopting larger-scale and more in-depth data statistics. The differences between regions can be considered, and therefore further promotes the elderly-friendly city development at a local level. The main limitation of the study lies in the survey object and the size of the survey sample. In this paper, Shanghai, a city with a serious aging trend, is selected as the research object, and its representative streets are selected as the empirical research object. The needs and evaluations of the elderly in other types of cities and streets should be further studied and compared. Further, our social survey was carried out manually, and was not combined with the big data collection method, resulting in a small sample size compared with the huge population of the research object. Future studies can be combined with government-led urban physical examination to compensate for the shortcomings of existing research methods.