What Attributes of Meat Substitutes Matter Most to Consumers? The Role of Sustainability Education and the Meat Substitutes Perceptions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

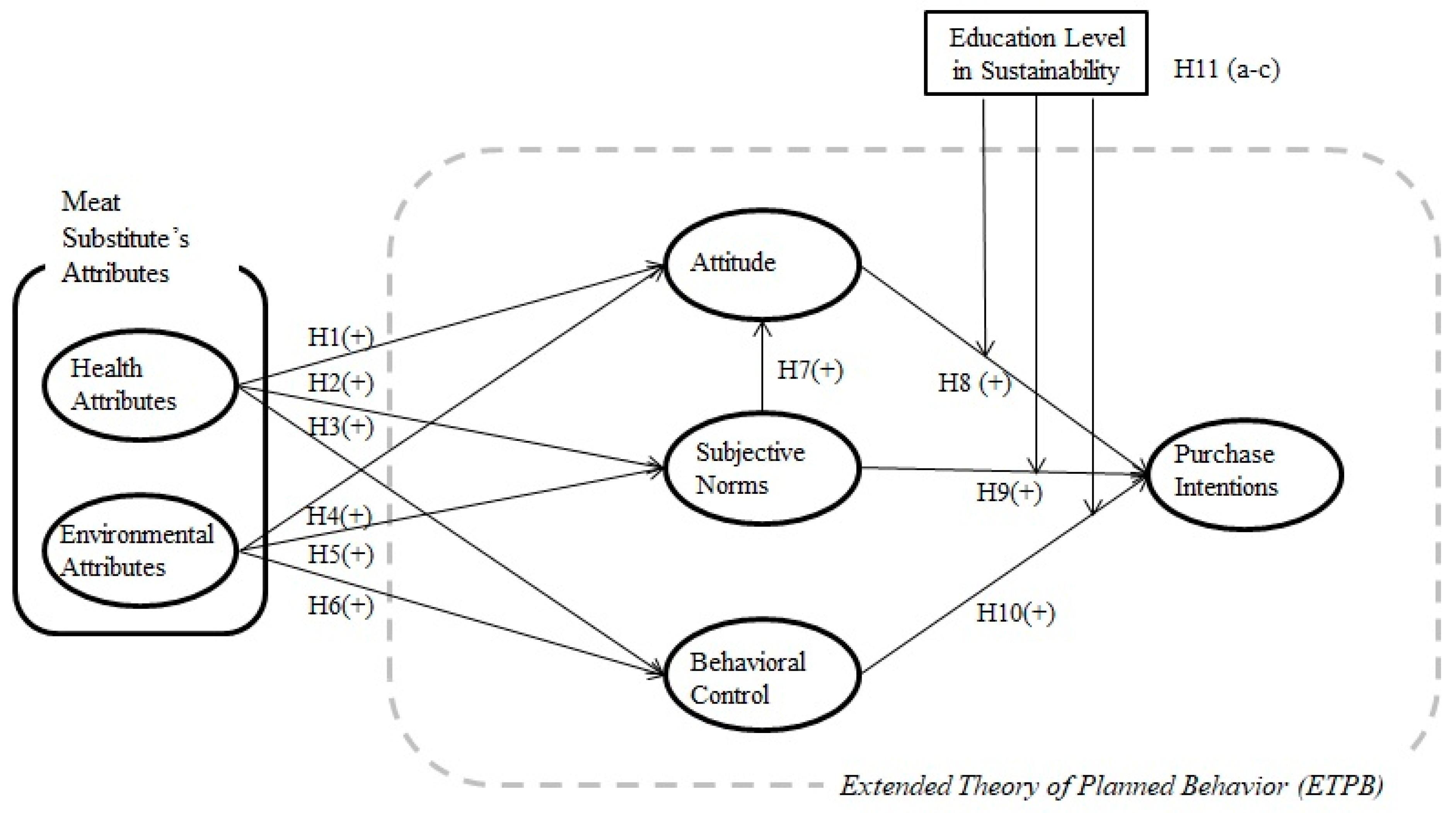

- This study examines the relationships between meat substitutes’ health and environmental attributes and consumer attitude, subjective norms, and behavioral control;

- Applying the extended TPB model, this study verifies the relationships between consumer attitude, subjective norms, and behavioral control and the meat substitutes’ purchase intention;

- This study investigates the moderating effect of education levels in sustainability (high vs. low) on the relationships between consumer attitude, subjective norms, behavioral control, and the meat substitutes’ purchase intention.

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Attributes of Meat Substitutes

2.2. Extended Theory of Planned Behavior (ETPB)

2.3. Meat Substitutes’ Attributes and Their Effects on Attitude, Subjective Norms, and Behavioral Control

2.4. Relationship between Subjective Norms and Attitude

2.5. Attitude, Subjective Norms, and Behavioral Control and Their Effect on the Intention to Purchase Meat Substitutes

2.6. Moderating Roles of Education Level in Sustainability

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Study Participants

3.2. Survey Instrument and Measures

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. Validity and Reliability of Measurements

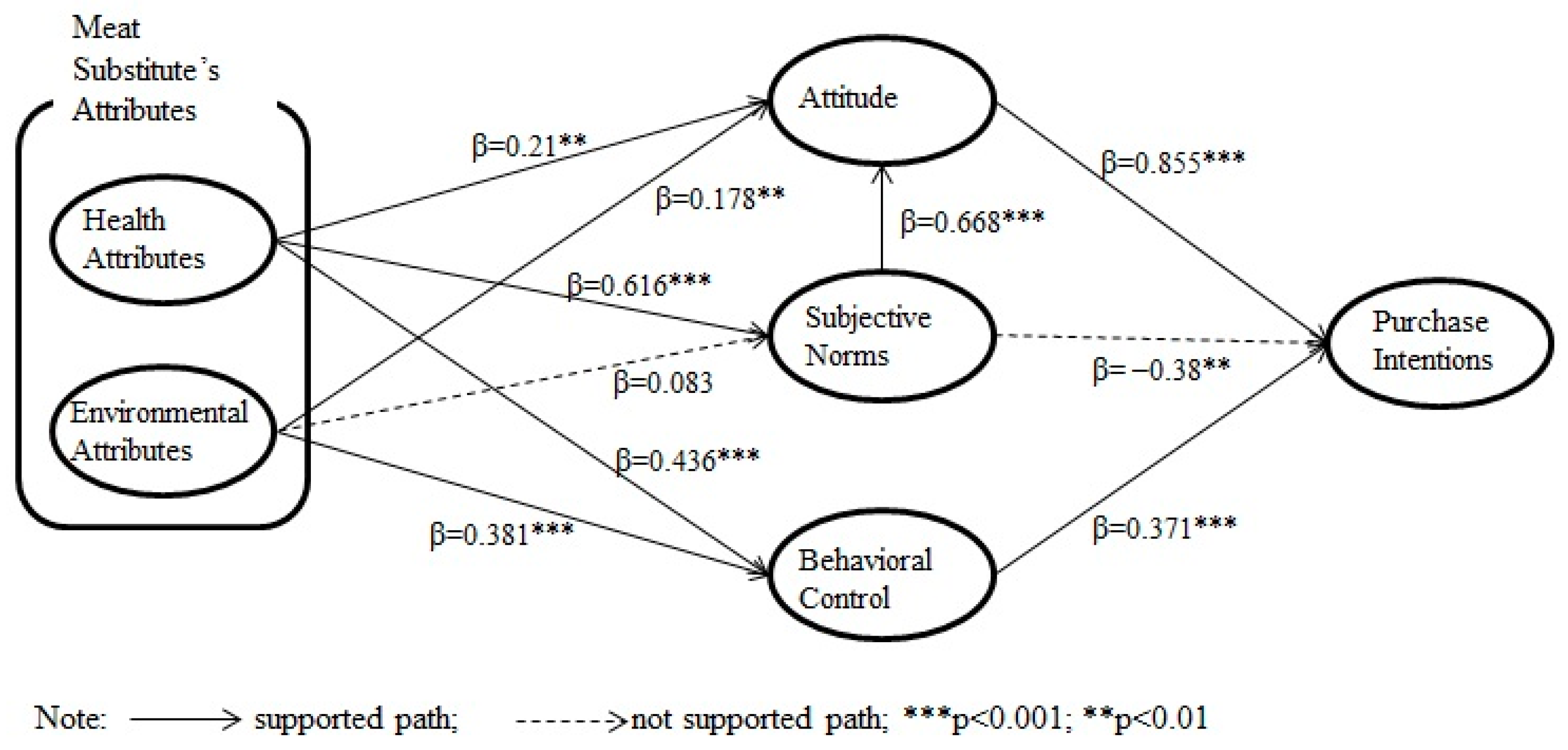

4.3. Results of Testing Hypotheses 1 through 10

4.4. Results of Testing Hypothesis 11

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stephens, W.O. Fake meat. In Encyclopedia of Food and Agricultural Ethics; Thompson, P.B., Kaplan, D.M., Eds.; Springer Nature: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, I.; Hwang, Y.H.; Joo, S.T. Meat analog as future food: A review. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2020, 62, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thavamani, A.; Sferra, T.J.; Sankararaman, S. Meet the meat alternatives: The value of alternative protein sources. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2020, 9, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayhall, T.A. The meat of the matter: Regulating a laboratory-grown alternative. Food Drug Law J. 2019, 74, 151. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, A. China’s New 5-Year Plan Is a Blueprint for the Future of Meat. Times News. 2022. Available online: https://time.com/6143109/china-future-of-cultivated-meat/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Tobias, N. Are Alternative Meats a Good Option for the Environment? Food Tank News. 2022. Available online: https://foodtank.com/news/2022/01/are-alternative-meats-a-good-option-for-the-environment/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Flink, T. Why the Best New Vegan Meat Products Will Come from Korea. Veg News. 2022. Available online: https://vegnews.com/2022/1/best-new-vegan-meat-products-korea (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Mancini, M.C.; Antonioli, F. To what extent are consumers’ perception and acceptance of alternative meat production systems affected by information? The case of cultured meat. Animals 2020, 10, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, R.A.; Edwards, D.; Palmer, A.; Ramsing, R.; Righter, A.; Wolfson, J. Reducing meat consumption in the USA: A nationally representative survey of attitudes and behaviours. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1835–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nestle, M. Is Fake Meat Better for Us—And the Planet—Than the Real Thing? Let.’s Ask Marion; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Santo, R.E.; Kim, B.F.; Goldman, S.E.; Dutkiewicz, J.; Biehl, E.M.B.; Bloem, M.W.; Neff, R.A.; Nachman, K.E. Considering plant-based meat substitutes and cell-based meats: A public health and food systems perspective. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Con. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Ham, S.; Yang, I.S.; Choi, J.G. The roles of attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control in the formation of consumers’ behavioral intentions to read menu labels in the restaurant industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Hancer, M. The role of attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and moral norm in the intention to purchase local food products. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2016, 19, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkiainen, A.; Sundqvist, S. Subjective norms, attitudes and intentions of Finnish consumers in buying organic food. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 808–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonnett, M. Education for sustainability as a frame of mind. Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Raath, S.; Lazzarini, B.; Vargas, V.R.; de Souza, L.; Anholon, R.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Haddad, R.; Klavins, M.; Orlovic, V.L. The role of transformation in learning and education for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 199, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J. Education as sustainability. Environ. Educ. Res. 2001, 7, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrib, A.R.; Pertiwi, N.; Dirawan, G.D. The effect of education level on Farmer’s behavior eco-friendly to application in Gowa, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Statistics, Mathematics, Teaching, and Research, Makassar, Indonesia, 9–10 October 2017; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018; Volume 1028, p. 012016. [Google Scholar]

- Kwol, V.S.; Eluwole, K.K.; Avci, T.; Lasisi, T.T. Another look into the Knowledge Attitude Practice (KAP) model for food control: An investigation of the mediating role of food handlers’ attitudes. Food Control 2020, 110, 107025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela-Candamio, L.; Novo-Corti, I.; García-Álvarez, M.T. The importance of environmental education in the determinants of green behavior: A meta-analysis approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 1565–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, I.A.; Amjed, S.; Jaboob, S. The moderating role of entrepreneurship education in shaping entrepreneurial intentions. J. Econ. Struct. 2020, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Regnier-Davies, J. Fake meat and Cabbageworms. Connecting Perceptions of Food Safety and Household Level Food Security in Urban China. Master’s Thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; You, J.; Moon, J.; Jeong, J. Factors affecting consumers’ alternative meats buying intentions: Plant-based meat alternative and cultured meat. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah Alam, S.; Mohamed Sayuti, N. Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) in halal food purchasing. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 2011, 21, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.; Ismail, A.; Alam, S.S.; Makhbul, Z.M.; Omar, N.A. Exploring the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) in relation to a halal food scandal: The Malaysia Cadbury chocolate case. Int. Food Res. J. 2018, 25, S79–S86. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Sherwani, M.; Ali, A.; Ali, Z.; Sherwani, S. The moderating role of individualism/collectivism and materialism: An application of the theory of planned behavior (TPB) in halal food purchasing. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2020, 26, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haro, A. Understanding TPB model, availability, and information on consumer purchase intention for halal food. Int. J. Bus. Com. 2016, 5, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Suleman, S.; Sibghatullah, A.; Azam, M. Religiosity, halal food consumption, and physical well-being: An extension of the TPB. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1860385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Swidi, A.; Mohammed Rafiul Huque, S.; Haroon Hafeez, M.; Noor Mohd Shariff, M. The role of subjective norms in theory of planned behavior in the context of organic food consumption. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1561–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalco, A.; Noventa, S.; Sartori, R.; Ceschi, A. Predicting organic food consumption: A meta-analytic structural equation model based on the theory of planned behavior. Appetite 2017, 112, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Intention to purchase organic food among young consumers: Evidences from a developing nation. Appetite 2016, 96, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choe, J.Y.; Kim, J.J.; Hwang, J. Innovative marketing strategies for the successful construction of drone food delivery services: Merging TAM with TPB. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F. Attitude toward organic foods among Taiwanese as related to health consciousness, environmental attitudes, and the mediating effects of a healthy lifestyle. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Yun, Z.S. Consumers’ perceptions of organic food attributes and cognitive and affective attitudes as determinants of their purchase intentions toward organic food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, M.I.; Sarwar, H.; Ahmed, R. ‘A healthy outside starts from the inside’: A matter of sustainable consumption behavior in Italy and Pakistan. Bus. Ethics Environ. Respons. 2021, 30, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayyam, M.; Chuanmin, S.; Qasim, H.; Ihtisham, M.; Anjum, R.; Jiaxin, L.; Tikhomirova, A.; Khan, N. Food consumption behavior of Pakistani students living in China: The role of food safety and health consciousness in the wake of coronavirus disease 2019 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 673771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, D.R.; Haddad, E.H.; Lee, J.W.; Johnston, P.K.; Hodgkin, G.E. Psychosocial predictors of healthful dietary behavior in adolescents. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2002, 34, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidwell, B.; Jewell, R.D. An examination of perceived behavioral control: Internal and external influences on intention. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 625–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.; Büssing, A.G.; Jarzyna, R.; Fiebelkorn, F. Do German student biology teachers intend to eat sustainably? Extending the theory of planned behavior with nature relatedness and environmental concern. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troise, C.; O’Driscoll, A.; Tani, M.; Prisco, A. Online food delivery services and behavioural intention–a test of an integrated TAM and TPB framework. Br. Food J. 2020, 123, 664–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkarimi, K.; Mansourian, M.; Kabir, M.J.; Ozouni-Davaji, R.B.; Eri, M.; Hosseini, S.G.; Qorbani, M.; Safari, O.; Mehr, B.R.; Noroozi, M.; et al. Fast food consumption behaviors in high-school students based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Int. J. Pediatr. 2016, 4, 2131–2142. [Google Scholar]

- Vabø, M.; Hansen, H. Purchase intentions for domestic food: A moderated TPB-explanation. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 2372–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Pradhan, R.K.; Panigrahy, N.P.; Jena, L.K. Self-efficacy and workplace well-being: Moderating role of sustainability practices. Benchmarking Int. J. 2019, 26, 1692–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Hallak, R. Investigating the moderating role of education on a structural model of restaurant performance using multi-group PLS-SEM analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlhan Ertuna, Z.I.; Gurel, E. The moderating role of higher education on entrepreneurship. Educ. Train. 2011, 53, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Capelleras, J.L.; Contín-Pilart, I.; Larraza-Kintana, M.; Martin-Sanchez, V. Unemployment and growth aspirations: The moderating role of education. Strateg. Chang. 2016, 25, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahverdi, M.; Ismail, K.; Qureshi, M.I. The effect of perceived barriers on social entrepreneurship intention in Malaysian universities: The moderating role of education. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2018, 8, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Hünnemeyer, A.; Veeman, M.; Adamowicz, W.; Srivastava, L. Trading off health, environmental and genetic modification attributes in food. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2004, 31, 389–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erten, I.H. Validating Myself-as-A-Learner Scale (MALS) in the Turkish context. Novitas-ROYAL Res. Youth Lang. 2015, 9, 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rohland, B.M.; Kruse, G.R.; Rohrer, J.E. Validation of a single-item measure of burnout against the Maslach Burnout Inventory among physicians. Stress Health 2004, 20, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, K.; Clemes, S.; Bull, F. Can a single question provide an accurate measure of physical activity? Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K. Tourism Research and Statistical Analysis; Daewangsa: Seoul, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Anderson, R.; Babin, B. Multivariate Data Analysis (8, illustrated ed.). Cengage Learn. EMEA 2018, 27, 1951–1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, J.S. Good Meat Will Replace Dead Meat. Readers News. 2022. Available online: https://www.readersnews.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=104807&replyAll=&reply_sc_order_by=C (accessed on 1 March 2022).

| Characteristics | n (%) | Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Monthly income | ||

| 18–19 | 0 (0%) | ≤USD 1000 | 30 (9.4%) |

| 20–29 | 82 (25.7%) | USD 1001–2000 | 38 (11.9%) |

| 30–39 | 100 (31.3%) | USD 2001–3000 | 104 (32.6%) |

| 40–49 | 94 (29.5%) | USD 3001–4000 | 53 (16.6%) |

| 50–59 | 33 (10.3%) | USD 4001–5000 | 44 (13.8%) |

| 60 or older | 10 (3.1%) | USD 5001≤ | 50 (15.7%) |

| Gender | Occupation | ||

| Men | 157 (49.2%) | Student | 36 (11.3%) |

| Women | 162 (50.8%) | Office job | 145 (45.5%) |

| Marital status | Self-employed | 21 (6.6%) | |

| Unmarried | 165 (51.7%) | Professional job | 61 (19.1%) |

| Married | 150 (47%) | Homemaker | 31 (9.7%) |

| Other | 4 (1.3%) | Other | 25 (7.8%) |

| Educational level | |||

| High school | 41 (12.9%) | ||

| Two-year college | 53 (16.6%) | ||

| University | 187 (58.6%) | ||

| Graduate school | 38 (11.9%) |

| Construct | Standardized Loadings | t-Value | AVEa | CCRb | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ndardHealth Attributes | 0.695 | 0.901 | 0.901 | ||

| Meat substitutes are beneficial to health | 0.808 | Fixed | |||

| Meat substitutes consist of nutrients that are beneficial to health | 0.795 | 15.969 | |||

| Meat substitutes help our health in many ways | 0.864 | 17.925 | |||

| Meat substitutes have various benefits for health | 0.866 | 17.999 | |||

| Environmental Attributes | 0.675 | 0.892 | 0.893 | ||

| Meat substitutes are environmentally friendly ingredients | 0.784 | Fixed | |||

| Meat substitutes are an environmentally friendly food | 0.845 | 16.427 | |||

| Meat substitutes have many benefits for the environment | 0.828 | 16.030 | |||

| Meat substitute consumption is a solution to protect our environment | 0.828 | 16.017 | |||

| Attitudes | 0.625 | 0.869 | 0.879 | ||

| I prefer meat substitutes because they are more nutritious than real meat | 0.782 | Fixed | |||

| I prefer meat substitutes as they cause fewer diseases than real meat | 0.803 | 20.848 | |||

| I prefer meat substitutes because they are environment-friendly food | 0.739 | 13.937 | |||

| It is exciting for me to eat meat substitutes | 0.834 | 16.170 | |||

| Subjective Norms | 0.677 | 0.893 | 0.894 | ||

| The trend of buying meat substitutes among people around me is increasing | 0.812 | Fixed | |||

| People around me generally believe that it is better for health to use meat substitutes | 0.814 | 16.578 | |||

| My close friends and family members would appreciate it if I bought meat substitutes | 0.813 | 16.553 | |||

| My close friends and family members would appreciate it if I chose meat substitutes | 0.851 | 17.641 | |||

| Behavioral Control | 0.565 | 0.795 | 0.791 | ||

| I can take the decision to buy meat substitutes independently | 0.754 | Fixed | |||

| I have the time to buy meat substitutes | 0.72 | 12.349 | |||

| I can handle any (money, time, information-related) difficulties associated with my buying decision | 0.779 | 13.369 | |||

| Purchase Intentions | 0.731 | 0.916 | 0.913 | ||

| I would look for specialty shops to buy meat substitutes | 0.882 | Fixed | |||

| I am willing to buy meat substitutes in future | 0.867 | 21.327 | |||

| I am willing to buy meat substitutes regularly | 0.85 | 20.513 | |||

| I would also recommend to others to buy meat substitutes | 0.819 | 19.157 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Mean | SDb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Health Attributes | 0.833a | 3.518 | 0.743 | |||||

| 2. Environmental Attributes | 0.727 | 0.821a | 3.717 | 0.719 | ||||

| 3. Attitude | 0.702 | 0.632 | 0.79a | 3.159 | 0.837 | |||

| 4. Subjective Norms | 0.620 | 0.531 | 0.807 | 0.822a | 2.991 | 0.88 | ||

| 5. Behavioral Control | 0.618 | 0.617 | 0.667 | 0.667 | 0.751a | 3.373 | 0.797 | |

| 6. Purchase Intentions | 0.657 | 0.626 | 0.746 | 0.642 | 0.678 | 0.854a | 3.431 | 0.876 |

| Structural Relationship | High (n = 131) | Low (n = 79) | Free | Constrained | Δχ2 | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-Value | t-Value | χ2 (df = 116) | χ2 (df = 115) | ||||||

| H11a | A→PI | 0.386 | 1.492 | 0.336 | 1.402 | 919.657 | 919.783 | 0.126 | Not Supported |

| H11b | SN→PI | −0.166 | −0.778 | 0.286 | 1.218 | 919.657 | 921.489 | 1.832 | Not Supported |

| H11c | BC→PI | 0.585 | 4.312 *** | 0.088 | 0.864 | 919.657 | 923.600 | 3.943 | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jang, H.-W.; Cho, M. What Attributes of Meat Substitutes Matter Most to Consumers? The Role of Sustainability Education and the Meat Substitutes Perceptions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4866. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094866

Jang H-W, Cho M. What Attributes of Meat Substitutes Matter Most to Consumers? The Role of Sustainability Education and the Meat Substitutes Perceptions. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):4866. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094866

Chicago/Turabian StyleJang, Ha-Won, and Meehee Cho. 2022. "What Attributes of Meat Substitutes Matter Most to Consumers? The Role of Sustainability Education and the Meat Substitutes Perceptions" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 4866. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094866

APA StyleJang, H.-W., & Cho, M. (2022). What Attributes of Meat Substitutes Matter Most to Consumers? The Role of Sustainability Education and the Meat Substitutes Perceptions. Sustainability, 14(9), 4866. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094866