The Clean Your Plate Campaign: Resisting Table Food Waste in an Unstable World

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- RQ1: What kinds of clean plate campaigns have been carried out?

- RQ2: What are the factors that influence table food waste?

- RQ3: In terms of policy factors, what are the characteristics and effects of the various anti-food waste laws?

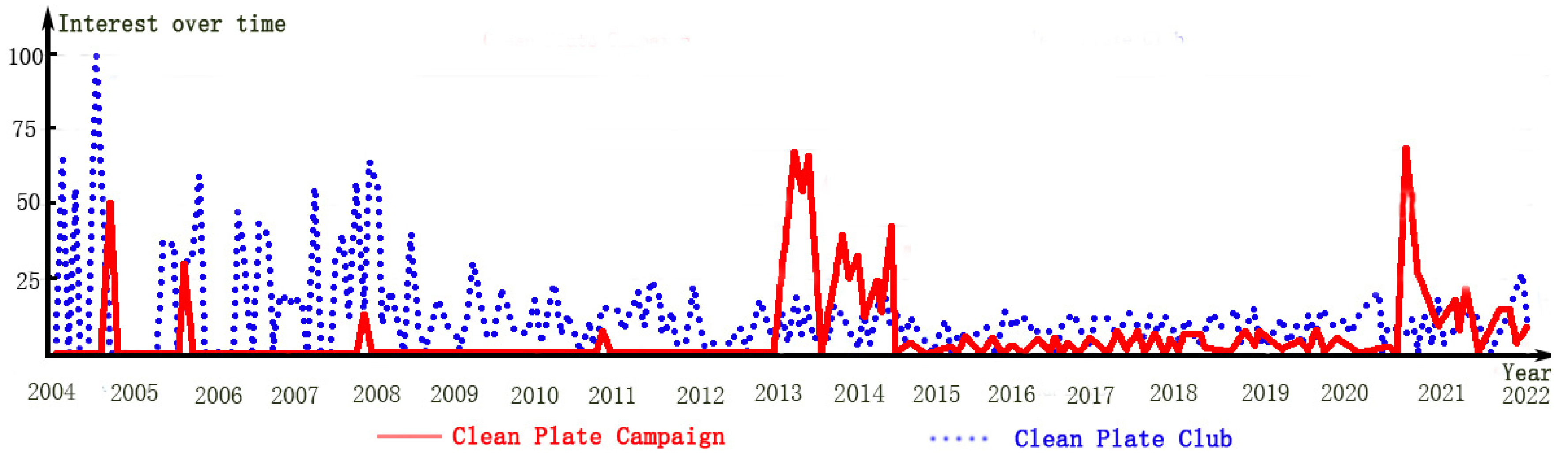

2. Clean Plate Campaigns around the World

2.1. Basic Description

2.2. Comparison of Different Countries

3. The Factors That Influence Food Waste

3.1. Behavioral Interventions

3.2. Cultural Factors

3.3. Political Factors

3.4. COVID-19 Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Babbitt, C.W.; Babbitt, G.A.; Oehman, J.M. Behavioral impacts on residential food provisioning, use, and waste during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nutritionlibrary/publications/state-food-security-nutrition-2020-inbrief-en.pdf?sfvrsn=65fbc6ed_4 (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ca6030en/ca6030en.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Foresight. The Future of Food and Farming: Final Project Report; Foresight: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Global Food Losses and Food Waste. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/mb060e/mb060e00.pdf#:~:text=The%20results%20of%20the%20study%20suggest%20that%20roughly,amounts%20to%20about%201.3%20billion%20tons%20per%20year (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- UNEP. UNEP Food Waste Index Report 2021. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021 (accessed on 26 January 2022).

- Ishangulyyev, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.H. Understanding Food Loss and Waste-Why Are We Losing and Wasting Food? Foods 2019, 8, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thyberg, K.L.; Tonjes, D.J. Drivers of food waste and their implications for sustainable policy development. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 106, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Food Wastage Footprint: Impacts on Natural Resources. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i3347e/i3347e.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Roodhuyzen, D.M.A.; Luning, P.A.; Fogliano, V.; Steenbekkers, L.F.A. Putting together the puzzle of consumer food waste: Towards an integral perspective. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 68, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.; Sobal, J.; Lyson, T.A. An analysis of a community food waste stream. Agric. Hum. Values 2009, 26, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secondi, L.; Principato, L.; Laureti, T. Household food waste behaviour in EU-27 countries: A multilevel analysis. Food Policy 2015, 56, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummu, M.; De Moel, H.; Porkka, M.; Siebert, S.; Varis, O.; Ward, P.J. Lost food, wasted resources: Global food supply chain losses and their impacts on freshwater, cropland, and fertiliser use. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 438, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfitt, J.; Barthel, M.; Macnaughton, S. Food waste within food supply chains: Quantification and potential for change to 2050. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 3065–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qian, L.; Li, F.; Liu, H.B.; Wang, L.G.; McCarthy, B.; Jin, S.S. Rice vs. Wheat: Does staple food consumption pattern affect food waste in Chinese university canteens? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 176, 105902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velez, C.; Majda, S.; Wansink, B. The Clean Plate Club’s: Multi-Generational Impact on Child and Adult BMI. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B.; Johnson, K.A. Adults only: Why don’t children belong to the clean-plate club? REPLY. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 39, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.S.; Kim, S.W.; Jung, S.Y.; Choi, B.D.; Mun, S.J.; Lee, D.H. Clean plate movement and empowerment of civil leadership for developing sustainable life style. In Proceedings of the World Summit on Knowledge Society, Mykonos, Greece, 21–23 September 2010; pp. 405–411. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.-K.; Kim, D.-G.; Kim, S.-W.; Jung, S.-Y.; Choi, K.-S. Effect of Clean Plate Education on Food Wastes Reduction in University Dormitory. J. Environ. Sci. Int. 2012, 21, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xian, J.N.; Bian, J. China Launches Clean Plate Campaign 2.0 as Xi Calls for End to Food Wastage. Available online: http://en.people.cn/n3/2020/0813/c90000-9721038.html (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Choksey, T. Mission Clean Plate 2.0—China’s Anti-Food Wastage Campaign. Available online: https://www.eatmy.news/2021/04/mission-clean-plate-20-chinas-anti-food.html (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Song, D. Xu Zhijun: A New Era at the Table. 2021, p. 5. Available online: http://www.eeo.com.cn/2021/0417/485204.shtml (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Zhao, Z.Q. Keeping the “Food” in Mind: Making Frugality a Conscious Action. The People’s Congress of China. 2020, pp. 25–27. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2020&filename=ZGRE202018008&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=tm8Ke-7BlVEfoqyLavOK8xZot7jNgTF-UFbeEeIZlHiqwDzM-peLLN_VGNwcDdpA (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Wang, Q. China Launches Clean Plate Campaign 2.0 as Xi Calls for End to Food Wastage. Available online: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202008/1197577.shtml (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Priefer, C.; Jörissen, J.; Bräutigam, K.-R. Food waste prevention in Europe—A cause-driven approach to identify the most relevant leverage points for action. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 109, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyen, M.; Sirieix, L. How does a local initiative contribute to social inclusion and promote sustainable food practices? Focus on the example of social cooking workshops. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamri, G.B.; Azizal, N.K.A.; Nakamura, S.; Okada, K.; Nordin, N.H.; Othman, N.; Nadia, F.; Sobian, A.; Kaida, N.; Hara, H. Delivery, impact and approach of household food waste reduction campaigns. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 118969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, V.; Haugaard, P.; Lähteenmäki, L. Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: Two routes to food waste. Appetite 2016, 96, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WRAP. UK Progress Against Courtauld 2025 Targets and UN Sustainable Development Goal 12.3. Available online: https://wrap.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-09/UK-progress-against-Courtauld-2025-targets-and-UN-SDG-123.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2021).

- Haque, A.; Karunasena, G.G.; Pearson, D. Household food waste and pathways to responsible consumer behaviour: Evidence from Australia. Br. Food J. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porpino, G. Household food waste behavior: Avenues for future research. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2016, 1, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jungowska, J.; Kulczynski, B.; Sidor, A.; Gramza-Michalowska, A. Assessment of Factors Affecting the Amount of Food Waste in Households Run by Polish Women Aware of Well-Being. Sustainability 2021, 13, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, V.; van Herpen, E.; Tudoran, A.A.; Lähteenmäki, L. Avoiding food waste by Romanian consumers: The importance of planning and shopping routines. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritikou, T.; Panagiotakos, D.; Abeliotis, K.; Lasaridi, K. Investigating the Determinants of Greek Households Food Waste Prevention Behaviour. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Wang, X.B.; Yu, X.H. Does dietary knowledge affect household food waste in the developing economy of China? Food Policy 2021, 98, 101896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörissen, J.; Priefer, C.; Bräutigam, K.-R. Food waste generation at household level: Results of a survey among employees of two European research centers in Italy and Germany. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2695–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, H.; Wikström, F.; Otterbring, T.; Löfgren, M.; Gustafsson, A. Reasons for household food waste with special attention to packaging. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 24, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abeliotis, K.; Lasaridi, K.; Chroni, C. Attitudes and behaviour of Greek households regarding food waste prevention. Waste Manag. Res. 2014, 32, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda, J.; Karunasena, G.G.; Mitsis, A.; Kansal, M.; Pearson, D. Analysing behavioural and socio-demographic factors and practices influencing Australian household food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 306, 127280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hooge, I.E.; Oostindjer, M.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Normann, A.; Loose, S.M.; Almli, V.L. This apple is too ugly for me!: Consumer preferences for suboptimal food products in the supermarket and at home. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 56, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivupuro, H.K.; Hartikainen, H.; Silvennoinen, K.; Katajajuuri, J.M.; Heikintalo, N.; Reinikainen, A.; Jalkanen, L. Influence of socio-demographical, behavioural and attitudinal factors on the amount of avoidable food waste generated in Finnish households. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.Q.; Yu, T.E.; Huang, W.Z.; Wang, Z.H. Home Food Waste in China and the Associated Determinants. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2018, 9, 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hazuchova, N.; Antosova, I.; Stavkova, J. Food wastage as a display of consumer behaviour. J. Compet. 2020, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chammas, G.; Yehya, N.A. Lebanese meal management practices and cultural constructions of food waste. Appetite 2020, 155, 104803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilska, B.; Tomaszewska, M.; Kolozyn-Krajewska, D. Analysis of the Behaviors of Polish Consumers in Relation to Food Waste. Sustainability 2020, 12, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grasso, A.C.; Olthof, M.R.; Boeve, A.J.; van Dooren, C.; Lahteenmaki, L.; Brouwer, I.A. Socio-Demographic Predictors of Food Waste Behavior in Denmark and Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dolan, P.; Hallsworth, M.; Halpern, D.; King, D.; Vlaev, I. Mindspace: Influencing Behavior Through Public Policy; The Institute for Government and Cabinet Office: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, F. First Goal of David Cameron’s ‘Nudge Unit’ is to Encourage Healthy Living. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2010/nov/12/david-cameron-nudge-unit (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Manomaivibool, P.; Chart-asa, C.; Unroj, P. Measuring the impacts of a save food campaign to reduce food waste on campus in Thailand. Appl. Environ. Res. 2016, 38, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Duan, H.; Andric, J.M.; Song, M.; Yang, B. Characterization of household food waste and strategies for its reduction: A Shenzhen City case study. Waste Manag. 2018, 78, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehair, K.J.; Shanklin, C.W.; Brannon, L.A. Written messages improve edible food waste behaviors in a university dining facility. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Roe, B.E. Foodservice Composting Crowds Out Consumer Food Waste Reduction Behavior in a Dining Experiment. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 99, 1159–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.Y. A study on the impact of the Clean Your Plate Compaign on the restaurant industry and countermeasures. Manag. Obs. 2014, 32–33. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2014&filename=GLKW201425013&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=kWL-Z_6rZ6VZdUp8i2jupawwqyj0c1fzDSDGqrStuMb4bj5m4QAJ-66QPFQl6t7Z (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Wang, Z.; Liao, W.; Zhang, W. Can “Clear Dishes” Action Reduce Grain Waste in Universities and Colleges?—Based on 237 Questionnaires of Students of Universities and Colleges in Beijing. Agric. Econ. Manag. 2018, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe, J.J.; Ellison, B.; Hamdi, N.; Richardson, R.; Prescott, M.P. A systematic review of school meal nudge interventions to improve youth food behaviors. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 237, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.A.; Bruening, M.; Ohri-Vachaspati, P.; Hurley, J.C. Location of school lunch salad bars and fruit and vegetable consumption in middle schools: A cross-sectional plate waste study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallbekken, S.; Slen, H. ‘Nudging’ hotel guests to reduce food waste as a win–win environmental measure. Econ. Lett. 2013, 119, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B.; Van Ittersum, K. Portion size me: Plate-size induced consumption norms and win-win solutions for reducing food intake and waste. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2013, 19, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, S.; Block, L.G.; Keller, P.A. Of waste and waists: The effect of plate material on food consumption and waste. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2016, 1, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.; Goucher, L.; Quested, T.; Bromley, S.; Gillick, S.; Wells, V.K.; Evans, D.; Koh, L.; Kanyama, A.C.; Katzeff, C.; et al. Review: Consumption-stage food waste reduction interventions—What works and how to design better interventions. Food Policy 2019, 83, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaney, L.; Davies, A.R. Disrupting household food consumption through experimental HomeLabs: Outcomes, connections, contexts. J. Consum. Cult. 2017, 17, 823–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rozin, P. Food choice: An introduction. In Understanding Consumers of Food Products; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dhar, A.R.; Oita, A.; Matsubae, K. The Effect of Religious Dietary Cultures on Food Nitrogen and Phosphorus Footprints: A Case Study of India. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelradi, F. Food waste behaviour at the household level: A conceptual framework. Waste Manag. 2018, 71, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, E.A.; Xie, H.J.; Gurel-Atay, E.; Kahle, L.R. Greening up because of God: The relations among religion, sustainable consumption and subjective well-being. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, E.A.; Kahle, L.R.; Kim, C.H. Religion and motives for sustainable behaviors: A cross-cultural comparison and contrast. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1937–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhoushy, S.; Jang, S. Religiosity and food waste reduction intentions: A conceptual model. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; de Hooge, I.; Amani, P.; Bech-Larsen, T.; Oostindjer, M. Consumer-Related Food Waste: Causes and Potential for Action. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6457–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bloom, J. American Wasteland: How America Throws Away Nearly Half of Its Food (and What we Can Do About It); Da Capo Lifelong Books: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Minton, E.A.; Johnson, K.A.; Vizcaino, M.; Wharton, C. Is it godly to waste food? How understanding consumers’ religion can help reduce consumer food waste. J. Consum. Aff. 2020, 54, 1246–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmenofi, A.; Capone, R.; Waked, S.; Debs, P.; Bottalico, F.; El Bilali, H. An exploratory survey on household food waste in Egypt. In Proceedings of the VI International Scientific Agriculture Symposium Agrosym, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 15–18 October 2015; pp. 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Abiad, M.G.; Meho, L.I. Food loss and food waste research in the Arab world: A systematic review. Food Secur. 2018, 10, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.; Sobaih, A.E.; Alyahya, M.; Abu Elnasr, A. The Impact of Religiosity and Food Consumption Culture on Food Waste Intention in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Matute, J.; Kubal-Czerwinska, M.; Krzesiwo, K.; Mika, M. The determinants of consumer engagement in restaurant food waste mitigation in Poland: An exploratory study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelau, C.; Sarbu, R.; Serban, D. Cultural Influences on Fruit and Vegetable Food-Wasting Behavior in the European Union. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halloran, A.; Clement, J.; Kornum, N.; Bucatariu, C.; Magid, J. Addressing food waste reduction in Denmark. Food Policy 2014, 49, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirani, S.I.; Arafat, H.A. Reduction of food waste generation in the hospitality industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 132, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiak, M.; Butovskaya, M.; Sorokowski, P. Ecology shapes moral judgments towards food-wasting behavior: Evidence from the Yali of West Papua, the Ngorongoro Maasai, and Poles. Appetite 2018, 125, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozin, P. The meaning of food in our lives: A cross-cultural perspective on eating and well-being. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2005, 37, S107–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condrasky, M.; Ledikwe, J.H.; Flood, J.E.; Rolls, B.J. Chefs’ opinions of restaurant portion sizes. Obesity 2007, 15, 2086–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geier, A.B.; Rozin, P.; Doros, G. Unit bias: A new heuristic that helps explain the effect of portion size on food intake. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 17, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirola, N.; Sutinen, U.M.; Narvanen, E.; Mesiranta, N.; Mattila, M. Mottainai!—A Practice Theoretical Analysis of Japanese Consumers’ Food Waste Reduction. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baig, M.B.; Al-Zahrani, K.H.; Schneider, F.; Straquadine, G.S.; Mourad, M. Food waste posing a serious threat to sustainability in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—A systematic review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.T.; Juvan, E.; Qiu, H.Q.; Dolnicar, S. Context- and culture-dependent behaviors for the greater good: A comparative analysis of plate waste generation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.J.; McCarthy, B.; Kapetanaki, A.B. To be ethical or to be good? The impact of ‘Good Provider’ and moral norms on food waste decisions in two countries. Glob. Environ. Change-Hum. Policy Dimens. 2021, 69, 102300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschers, V.H.M.; Wickli, N.; Siegrist, M. Sorting out food waste behaviour: A survey on the motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.H. Chinese Characteristics; Shuhai Publishing House: Taiyuan, China, 2004; p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- He, A.Z.; Deng, T.X. A study on the mechanism of typical non-green consumption behaviour. Bus. Manag. J. 2014, 36, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, C.H.; Hong, J.; Zhao, D.T.; Zhang, S.; Chen, C.H. Confucian Culture as Determinants of Consumers’ Food Leftover Generation: Evidence from Chengdu, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 14919–14933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.G.; Hu, X.J. Face: The Chinese Power Game; China Renmin University Press (CRUP): Beijing, China, 2004; p. 242. [Google Scholar]

- Fen, B.Y. Favor Society and Contract Society: On the Perspective of Theory of Social Exchange. J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.E.; Liu, G.; Liu, X.J.; Liu, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhou, B.; Gao, S.; Cheng, S.K. The weight of unfinished plate: A survey based characterization of restaurant food waste in Chinese cities. Waste Manag. 2017, 66, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culliford, A.; Bradbury, J. A cross-sectional survey of the readiness of consumers to adopt an environmentally sustainable diet. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monier, V.; Shailendra, M.; Escalon, V.; O’Connor, C.; Gibon, T.; Anderson, G.; Hortense, M.; Reisinger, H. Preparatory Study on Food Waste across EU 27. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/eussd/pdf/bio_foodwaste_report.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Gao, Y. Policy of Ensuring Food Security of China in 1990-ies. Nauchnyi Dialog. 2017, 10, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, J.J. Suggestion of Special Legislation to Curb Food Waste. Sci. Technol. Cereals Oils Foods 2021, 29, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, M.B.; Henderson, K.E.; Read, M.; Danna, N.; Ickovics, J.R. New school meal regulations increase fruit consumption and do not increase total plate waste. Child. Obes. 2015, 11, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittuari, M.; Azzurro, P.; Gaiani, S.; Gheoldus, M.; Burgos, S.; Aramyan, L.; Valeeva, N.; Rogers, D.; Ostergren, K.; Timmermans, T.; et al. Recommendations and Guidelines for a Common European Food Waste Policy Framework; Bologna, Italy, 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316351481 (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Giordano, C.; Falasconi, L.; Cicatiello, C.; Pancino, B. The role of food waste hierarchy in addressing policy and research: A comparative analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinko, K. France Passes New Law Forbidding Food Waste. Available online: https://www.treehugger.com/france-passes-new-law-forbidding-food-waste-4850682 (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Saltzman, M.; Livesay, C.; Bittman, M. Is France’s Groundbreaking Food-Waste Law Working? Available online: https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/frances-groundbreaking-food-waste-law-working (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Mourad, M.; Finn, S. France’s Ban on Food Waste Three Years Later. Available online: https://foodtank.com/news/2019/06/opinion-frances-ban-on-food-waste-three-years-later/ (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Eubanks, L.B. From A Culture of Food Waste to A Culture of Food Security: A Comparison of Food Waste Law and Policy in France and in The United States. Wm. Mary Envtl. L. Poly Rev. 2018, 43, 667. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, C.; Franco, S. Household Food Waste from an International Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busetti, S. A theory-based evaluation of food waste policy: Evidence from Italy. Food Policy 2019, 88, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayako, K. New Japan Law to Aid Food Banks and Spread Food Loss Awareness. Available online: https://zenbird.media/new-japan-law-to-aid-food-banks-and-spread-food-loss-awareness/ (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Aldaco, R.; Hoehn, D.; Laso, J.; Margallo, M.; Ruiz-Salmon, J.; Cristobal, J.; Kahhat, R.; Villanueva-Rey, P.; Bala, A.; Batlle-Bayer, L.; et al. Food waste management during the COVID-19 outbreak: A holistic climate, economic and nutritional approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 742, 140524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guney, O.I.; Sangun, L. How COVID-19 affects individuals’ food consumption behaviour: A consumer survey on attitudes and habits in Turkey. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 2307–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, B.; McFadden, B.; Rickard, B.J.; Wilson, N.L. Examining food purchase behavior and food values during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2021, 43, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H.; Allahyari, M.S.; Berjan, S.; Fotina, O. Food purchase and eating behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey of Russian adults. Appetite 2021, 165, 105309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H.; Allahyari, M.S. Impact of COVID-19 on Food Behavior and Consumption in Qatar. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H.; Allahyari, M.S.; Al Samman, H.; Marzban, S. Observations on Food Consumption Behaviors During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Oman. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 779654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Kunugi, H. Apitherapy for Age-Related Skeletal Muscle Dysfunction (Sarcopenia): A Review on the Effects of Royal Jelly, Propolis, and Bee Pollen. Foods 2020, 9, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H.; Allahyari, M.S.; Karabasevic, D.; Radosavac, A.; Berjan, S.; Vasko, Z.; Radanov, P.; Obhodas, I. Food Behavior Changes during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Statistical Analysis of Consumer Survey Data from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murendo, C.; Manyanga, M.; Mapfungautsi, R.; Dube, T. COVID-19 nationwide lockdown and disruptions in the food environment in Zimbabwe. Cogent Food Agric. 2021, 7, 1945257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H.; Allahyari, M.S.; Morrar, R. Food attitudes and consumer behavior towards food in conflict-affected zones during the COVID-19 pandemic: Case of the Palestinian territories. Br. Food J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H.; Allahyari, M.S.; Charbel, L. Food shopping, preparation and consumption practices in times of COVID-19: Case of Lebanon. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bilali, H.; Ben Hassen, T.; Chatti, C.B.; Abouabdillah, A.; Alaoui, S.B. Exploring Household Food Dynamics During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Morocco. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 724803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cranfield, J.A.L. Framing consumer food demand responses in a viral pandemic. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Rev. Can. D Agroecon. 2020, 68, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H.; Allahyari, M.S.; Berjan, S.; Karabasevic, D.; Radosavac, A.; Dasic, G.; Dervida, R. Preparing for the Worst? Household Food Stockpiling during the Second Wave of COVID-19 in Serbia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, K.; Vizcaino, M.; Wharton, C. COVID-19-Related Changes in Perceived Household Food Waste in the United States: A Cross-Sectional Descriptive Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brizi, A.; Biraglia, A. “Do I have enough food?” How need for cognitive closure and gender impact stockpiling and food waste during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-national study in India and the United States of America. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 168, 110396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkodie, S.A.; Owusu, P.A. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on waste management. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 7951–7960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bunditsakulchai, P.; Zhuo, Q.N. Impact of COVID-19 on Food and Plastic Waste Generated by Consumers in Bangkok. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsellino, V.; Kaliji, S.A.; Schimmenti, E. COVID-19 Drives Consumer Behaviour and Agro-Food Markets towards Healthier and More Sustainable Patterns. Sustainability 2020, 1, 8366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scacchi, A.; Catozzi, D.; Boietti, E.; Bert, F.; Siliquini, R. COVID-19 Lockdown and Self-Perceived Changes of Food Choice, Waste, Impulse Buying and Their Determinants in Italy: QuarantEat, a Cross-Sectional Study. Foods 2021, 10, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.H.; Ghazi, T.I.M.; Hamzah, M.H.; Manaf, L.A.; Tahir, R.M.; Nasir, A.M.; Omar, A.E. Impact of Movement Control Order (MCO) due to Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) on Food Waste Generation: A Case Study in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlea-Schiopoiu, A.; Ogarca, R.F.; Barbu, C.M.; Craciun, L.; Baloi, I.C.; Mihai, L.S. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on food waste behaviour of young people. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, F.; Scalvedi, M.L.; Scognamiglio, U.; Turrini, A.; Rossi, L. Eating Habits during the COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy: The Nutritional and Lifestyle Side Effects of the Pandemic. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jribi, S.; Ben Ismail, H.; Doggui, D.; Debbabi, H. COVID-19 virus outbreak lockdown: What impacts on household food wastage? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 3939–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pappalardo, G.; Cerroni, S.; Nayga, R.M.; Yang, W. Impact of Covid-19 on Household Food Waste: The Case of Italy. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 585090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Lombardo, C.; Cerolini, S.; Franko, D.L.; Omori, M.; Linardon, J.; Guillaume, S.; Fischer, L.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. “Waste not and stay at home” evidence of decreased food waste during the COVID-19 pandemic from the US and Italy. Appetite 2021, 160, 105110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicarelli, V.; Tricase, C.; Spada, A.; Bux, C. Households’ Food Waste Behavior at Local Scale: A Cluster Analysis after the COVID-19 Lockdown. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, B.; Reynolds, C.; Martins, C.A.; Frankowska, A.; Levy, R.B.; Rauber, F.; Osei-Kwasi, H.A.; Vega, M.; Cediel, G.; Schmidt, X.; et al. Food insecurity, food waste, food behaviours and cooking confidence of UK citizens at the start of the COVID-19 lockdown. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 2959–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Mones, B.; Barco, H.; Diaz-Ruiz, R.; Fernandez-Zamudio, M.A. Citizens’ Food Habit Behavior and Food Waste Consequences during the First COVID-19 Lockdown in Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Javadi, F.; Hiramatsu, M. Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Household Food Waste Behavior in Japan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.S.; Kallas, Z.; Rahmani, D. Did the COVID-19 lockdown affect consumers’ sustainable behaviour in food purchasing and consumption in China? Food Control 2022, 132, 108352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wang, C.; Cui, Z.L.; Liu, X.J.; Jiang, J.; Yin, J.; Feng, H.J.; Dou, Z.X. COVID-19 affected the food behavior of different age groups in Chinese households. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoddard, G. I Want to Stop Cleaning My Plate out of Habit. Available online: https://www.openfit.com/why-you-are-not-losing-weight-clean-plate-club (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Liu, R. The derivation and evolution of ancient Chinese dining styles. Cult. J. 2014, 151–154. Available online: https://t.cnki.net/kcms/detail?v=F8ybyWdFT3UdtmOhlYYvQawY_RUho7NRrTRUp3yz1zu27DNHiz3BIgbe5GTUU8FMlwYt1nmlAbD4eFuiGdAaU90YVmb1coIxlt7MTq-mgdsW8pNdhaRSg==&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Porpino, G.; Parente, J.; Wansink, B. Food waste paradox: Antecedents of food disposal in low income households. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aleshaiwi, A.; Harries, T. A step in the journey to food waste: How and why mealtime surpluses become unwanted. Appetite 2021, 158, 105040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisanne, V.G.; Herpen, E.V.; Sijtsema, S.; Trijp, H.V. Food waste as the consequence of competing motivations, lack of opportunities, and insufficient abilities. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 5, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenmarck, A.; Jensen, C.; Quested, T.; Moates, G. Estimates of European Food Waste Levels. Available online: https://www.eu-fusions.org/phocadownload/Publications/Estimates%20of%20European%20food%20waste%20levels.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Delley, M.; Brunner, T.A. Household food waste quantification: Comparison of two methods. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1504–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cequea, M.M.; Neyra, J.M.V.; Schmitt, V.G.H.; Ferasso, M. Household Food Consumption and Wastage during the COVID-19 Pandemic Outbreak: A Comparison between Peru and Brazil. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, B.E.; Bender, K.; Qi, D.Y. The Impact of COVID-19 on Consumer Food WasteJEL codes. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2021, 43, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| United States | South Korea | China | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Clean Plate Club | Clean Plate movement | CYPC I | CYPC II |

| Time period | Wartime | Daily | Daily | COVID-19 |

| Originator | Government agency | Formal social organization | Informal social organization | Government |

| Scale | 500,000 women volunteers, fourteen million families supported | 1000 volunteers, 1.5 million people pledged, pledge fund of 140,000 dollars was gathered | Nearly 30 members, CYPC was reposted 50 million times on Weibo, 60,000 leaflets were distributed, and over 5000 posters were put up in Beijing | Nationwide, conducted at all levels of government from top to bottom, with full participation of the catering industry and schools |

| The role of the state | Proposer, leader | Supporter, collaborators | Supporter | Proposer, leader |

| Main tactics | Political power, patriotic fervor | Religion (Buddhist philosophy) | Morality | Law, regulations |

| Others | 1. Citizens were urged to sign pledge cards 2. The US Food Administration was responsible | 1. Various targeted models: home model, school model, military model, restaurant model 2. The pledgers (except for children) were obligated to donate 1 dollar | 1. The campaign is advocacy, not compulsion 2. IN-33 offline activities were mainly in Beijing | 1. Backed by anti-food waste laws 2. The target group extends from officials to the public |

| France (https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000032036289, Accessed on 16 March 2022) | Italy (https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2016/08/30/16G00179/sg, Accessed on 16 March 2022) | Japan (https://perma.cc/LK8H-A8KU, accessed on 16 March 2022) | China (http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/c30834/202104/83b2946e514b449ba313eb4f508c6f29.shtml, Accessed on 16 March 2022) | |

| Adoption time | 11 February 2016 | 19 August 2016 | 24 May 2019 | 29 April 2021 |

| Main approach | Regulatory | Suasive | Suasive | Suasive |

| Main instrument | Public services | Market-based | Public services | Public services |

| Main objects | Retailers, charities | General public, catering service providers | Governments | Governments, catering service providers |

| Main stage | Re-use, prevention | Prevention, re-use | Prevention | Prevention |

| Funding | No | Yes | No | No |

| Donations | Mandatory (Fine) | Incentive (Tax reduction) | Supported | Guided |

| Main points | 1. Food retailers are forbidden to destroy unsold food products still fit for consumption. 2. Obligation to establish a partnership with a charity organization to donate unsold food products, for stores over 4305 square feet. | 1. Municipalities may apply a waste tax reduction for entities engaged in food donation. 2. For a donation below €15,000, no official procedures are required. 3. Donation of products that are beyond the minimum term of conservation is possible 4. The law establishes a stakeholders’ committee on food waste. | 1. Local municipalities will be urged to draft and act on their own plans. 2. October becomes the annual Food Loss Reduction Month 3. The law also sets up a body for the promotion of food loss reduction within the Cabinet Office. | 1. An anti-food waste supervision and inspection mechanism should be established. 2. Restaurants must provide small portions, display anti-waste signs, and offer packing services. 3. Prohibit the spread of content promoting food waste (overeating) or face fines. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, G. The Clean Your Plate Campaign: Resisting Table Food Waste in an Unstable World. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4699. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084699

Wang L, Yang Y, Wang G. The Clean Your Plate Campaign: Resisting Table Food Waste in an Unstable World. Sustainability. 2022; 14(8):4699. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084699

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Lingfei, Yuqin Yang, and Guoyan Wang. 2022. "The Clean Your Plate Campaign: Resisting Table Food Waste in an Unstable World" Sustainability 14, no. 8: 4699. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084699

APA StyleWang, L., Yang, Y., & Wang, G. (2022). The Clean Your Plate Campaign: Resisting Table Food Waste in an Unstable World. Sustainability, 14(8), 4699. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084699