Abstract

Montesinho Natural Park is one of the largest Portuguese natural protected areas, presenting good biodiversity and a cultural heritage with a strong connection to the territory and its people. It constitutes a low-density territory, characterized by a human and social landscape based on community practices, such as joint aid and the community use of goods and means of agricultural production, which have contributed to the construction of the “transmontana” identity and to the richness of the habitats. The promotion of the sustainable development of this low-density rural region demands the understanding of its specificities and an appropriate approach to grasp its challenges and develop effective management tools, allowing to preserve and exploit the region’s potential from various perspectives. The purpose of this article is to develop an analytical model using a literature review and a survey of the region’s specificities. This analytical model intends to provide the basis for designing and assessing sustainable development solutions, increasing local entrepreneurship and community empowerment through regional dynamism, with a focus on environment and heritage preservation, universal tourism accessibility, collective memory and endogenous product development. The suggested model adopts an interdisciplinary perspective and stresses that, in order to ensure that the new initiatives will contribute to the territory’s sustainable development, they should be scrutinized by asking four main questions: Is the initiative promoting the rural development of the territory through the creation of synergies between agroforestry and tourism activities? Is the initiative promoting an inclusive and sustainable tourism that is based on the territory’s resources? Are heritage and collective memory being preserved and valued through the initiative? Is the initiative promoting the empowerment of local communities?

1. Introduction

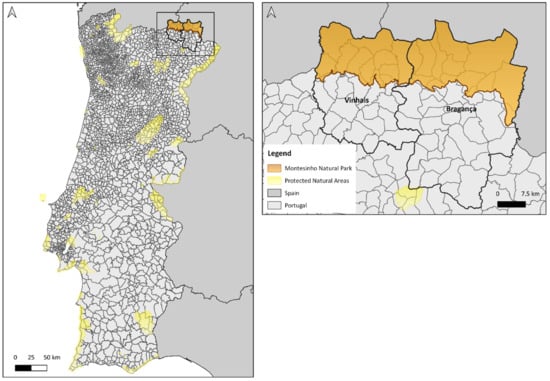

The Montesinho Natural Park (MNP) is one of several Portuguese regions with low population density, and it is located in the northeast of the country. It has a specific cultural and natural heritage, which must be studied and preserved. It is one of the largest Portuguese nature reserves, with a huge biodiversity and a cultural heritage strongly connected to the landscape and its people. The Park is distributed throughout the northern area of the municipalities of Bragança and Vinhais, bordering Spain.

The constant loss of inhabitants has led to the abandonment of several of its most characteristic and defining activities and a change in the organization of the region. At the same time, new business opportunities, associated with natural and cultural heritage and sustainability, have been slowly emerging, potentially making the region more attractive for population settlement, a fact that is not yet visible in the indicators.

In this context, arises the need for a developmental approach based on new scientific knowledge, to understand and to develop effective management tools to preserve and explore the region’s potential from several perspectives.

Research should support the creation of sustainable development solutions, increasing local entrepreneurship and enabling dissemination, and be based on the assumptions of environmental and heritage preservation and universal accessibility, thereby increasing the potential of the territory in economic and social terms. As part of the Tourism Strategy 2027 for Portugal, the country’s economic, social and environmental development must have tourism as a strategic reference, though ensuring the sustainability of the various regions. Currently, the tourism sector is one of the major levers of the Portuguese economic system, showing, in overall terms, a positive evolution since the beginning of the second decade of the twentieth century.

Based on these arguments, we propose the following hypothesis:

The characteristics of Montesinho Natural Park (natural and cultural heritage, collective memory, endogenous products, low-density rural area) can improve sustainable and accessible regional development through the implementation of innovative initiatives based on an interdisciplinary and integrated perspective.

The aim of this work, with an interdisciplinary scope, is to provide an analytical model that contributes to promote, in a sustainable way, the territory of the Montesinho Natural Park, creating conditions for the development of two strategic areas for the region: agroforestry and tourism. More specifically, it aims to develop an analytical framework that supports the emergence of concrete and viable proposals for the promotion of sustainable agroforestry activities and businesses and universally accessible cultural, historical, ethnographic and natural tourism. The study, therefore, addresses a relevant topic for scholars, policymakers and practitioners by providing a framework that can be used to design and assess development strategies for low-density regions that are based on innovative business models in tourism and agroforestry activities.

The remaining of the article is divided into four sections: the first will focus on the literature review and on the challenges of low-density rural regions and on rural tourism in those regions; the second will explain the socio-economic, cultural and geographical contextualization of Montesinho Natural Park; the third will present the suggested analytical framework for a development strategy of Montesinho Natural Park; and finally, the last section will present some concluding remarks.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Low-Density Rural Regions

Low-density rural regions face major socio-economic problems, such as desertification, ageing, unemployment the decline of infrastructure. They are considered to be economically less productive and are often captured in downward spirals due to the loss of inhabitants, especially young and highly skilled people [1]. The depopulation of rural areas has intensified since the mid-1950s in many European countries [2] and Portugal is not an exception [3]. Molinero [4,5] introduces the concept of “deep rural” areas to characterize these territories that have low population densities and are suffering from depopulation. Several economic factors are behind the depopulation trend, namely, those related to the lack of employment and business opportunities. Combating this trend requires the design of appropriate policies, which are often difficult to design and implement, to promote the sustainable development of low-density rural regions, particularly those affected by depopulation [2,6].

Since the late 1970s, scholars have made pleas for endogenous initiatives for the local socio-economic development of these territories, with growth based on home-grown assets and resources (e.g., natural resources, human capital, historically rooted skills and local business culture and traditions) [7,8]. More recently, and notably since the beginning of the 2010s, a paradigm shift has happened, with the emergence of the neo-endogenous development theory, which adds the idea that the development of any territory is both influenced by and dependent on the wider context in which it is embedded [6]. This paper adopts this perspective and understands rural development as a process that calls for the interaction between the endogenous knowledge and resources (available within the region) and the non-local knowledge and resources required for the development [9,10]. This perspective is in line with the place-based regional policy approach, which considers regional development to not be limited to endogenous development policies of local inspiration, but rather to include endogenous and exogenous dimensions, with the territory as the centrepiece of public policies, and the interaction of actors and institutions at several governance levels [11].

Until the 1960s, rural areas were mainly seen as spaces dominated by traditional agroforestry activities. Since then, other activities have gained expression, namely, landscape protection and a wide set of activities that respect the environment and its natural resources [12]. In fact, extant research has described a trend towards multifunctional agriculture in Europe [13], with a diversification in farmers’ activities, namely, by including tourism, biomass production, nature and landscape management and educational activities [14]. Nowadays, rural areas are also seen as spaces of multifunctional consumption, including leisure and recreation [15]. This multifunctionality of the rural territories can bring new opportunities for deep rural areas, which are usually dominated by agrarian activities [4]. Still, farmers’ livelihoods and rural development are closely related, as most of the rural populations still depend on agroforestry for their livelihoods. Resilient EU farmer livelihoods and the rural communities they support are crucial in the transition to sustainable systems [16].

Some scholars have been stressing the role of the development of new business models (BMs) in agroforestry and tourism activities, as part of an inclusive and sustainable approach, as an effective economic driver in the structurally weak low-density rural regions [17,18]. This would enable them to attract people and new business to the region and to promote its sustainable development, a concept that integrates the social, economic and environmental spheres [19].

Sustainable development in low-density regions that are largely dependent on agroforestry systems raises significant challenges [20]. Farmers need to innovate in several dimensions to create and implement new practices; to adapt to legislative, policy, market and environmental changes; to market their products; and to take part in collaborative processes. In this context, entrepreneurial initiatives may promote several types of innovations, helping rural areas to develop better and overcome the challenges they face [21,22]. Technological innovation, and, particularly, the use of digital technologies, is considered to be important in this process by promoting connectivity in the agri-food system and reducing inefficiencies in the value chain, with an impact on farmers’ incomes and increasing the sustainability of the system [23]. Social innovation, i.e., a process of social change that involves the empowerment of actors and the emergence of new ways of doing, organizing, knowing and framing [24], that contributes to the building of more sustainable, resilient and inclusive societies [25] is also increasingly considered to be important for the development of low-density rural territories [26,27], namely, under the neo-endogenous development approach [10]. Likewise, the literature is gradually stressing the need to introduce new practices that are based on new models of production and consumption, namely, regenerative agriculture and circular business models [28,29].

These changes (diversification, innovation and sustainability) demand the development of farmers’ entrepreneurial and organisational skills. Farms in Europe tend to be small and medium enterprises that face a set of constraints in terms of financial, human and social resources, hindering their capability to successfully change [30,31,32]. Networks (including informal contacts and formal partnerships) with a wide set of actors, namely, businesses from related sectors such as tourism and handicraft production, but also local authorities and communities, are considered to be important mechanisms for overcoming such constrains [33,34]. Accordingly, scholars progressively adopt a systematic approach to study innovation in rural contexts, where firms (e.g., farmers) interact with other stakeholders in multi-actor, multilevel systems to introduce change and promote local development [17,21].

2.2. Tourism in Low-Density Rural Regions

In the mid-1980s, it was argued that tourism in rural communities was one of the most appropriate options for the development of rural populations [35]. It is an activity that reconciles social equity and the preservation of natural and cultural heritage, without endangering future generations [36]. It is, therefore, a proposal of sustainability and local management in rural environments. Currently, the rural environment has come to be seen as an area that offers experiences related to rest, leisure and safety. Thus, it is interpreted through two prisms: as a tourist offer, by its local management, and as tourist demand, by travellers looking for new experiences [37].

Currently, tourism has an important impact on rural areas and livelihoods [38], since these areas have become attractive tourism destinations due to their landscape characteristics, which are based on rurality, traditional culture and history and natural attributes [39].

Several rural areas in Portugal are considered to be tourism destinations, despite being in an emergent phase but showing a great capacity for evolution and affirmation given their specific and distinctive characteristics [40]. This growing importance of tourism in rural areas was the result of European policies launched during the 1990s and 2000s, with the ultimate objective being to relaunch economic activity in these areas and turning them into multi-functional places [39,41]. Tourism and leisure services have been, thus, considered to be activities that are complementary to traditional agriculture practices that will help to arrest decline [41]. Even in these last years of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the tourism sector has suffered a significant decrease, these low-density rural areas have “suffered a less severe impact on tourism demand, and domestic tourism was able to mitigate some negative effect” ([42], p. 1). At the current juncture, rural tourism has the components to consolidate itself as a viable alternative for tourists by not generating crowds and developing in open and safe spaces [43].

However, the growth of tourism in these areas requires to balance the dynamic tension that characterizes the relationship between tourism development and the protection of the territory and its landscape [44], since tourism may impact negatively on natural and cultural resources [45].

New approaches to heritage management should be directed towards the sustainable development of local communities. One of these approaches, which has produced very interesting results, is the so-called working with people (WWP) model [46] for revitalizing rural areas through rural tourism, which has been mostly experimentally applied in Ayacucho (Argentina) [47].

These new approaches also advocate for the involvement of local people in the development of heritage management plans, since this will raise the awareness of residents to heritage value and contribute towards the sustainable protection of sites [8,48]. They also stress the need to consider the tourist experience in the management of heritage sites “to achieve the goal of sustainable heritage tourism” ([49], p. 269).

Although natural and cultural resources are the main attractions of a territory and the basis of its competitive advantage and endogenous growth, it is essential to take into account the way these resources are incorporated into qualified tourism products to satisfy the needs and expectations of tourist demand [50]. Thus, it is essential to have satisfied tourists and involved stakeholders to achieve sustainability in these heritage sites [49]. The sustainable management of natural and cultural heritage sites requires conciliation between conservation and the new economic and social function triggered by tourism. The practice of responsible tourism is essential, and the good use of heritage is the best guarantee of its conservation [51]. Providing accessibility to heritage sites is considered to be a way to promote the sustainable management of those regions. The concept of accessibility is usually characterized by physical and architectural aspects—space accessibility—but it goes much further, as it also concerns the accessibility of information, social, intellectual and emotional components. It means that all people, with or without special needs, must be able to participate in all activities that include the use of products, services or information [52,53].

Accessible, universal, inclusive or barrier-free tourism can be defined as tourism and travel accessible to all people, disabled or not, who may present temporary or permanent limitations concerning mobility, hearing, sight, cognitive, intellectual or psychosocial limitations [54,55]. It is associated with a way of thinking, planning and managing a specific destination, region or place. An accessible destination should allow all visitors, without exception, to enjoy and use equipment and services, without restrictions or constraints, in an equitable way.

3. The Montesinho Natural Park

3.1. Geographical Characterization

In the northeast of Portugal, in the so-called Terra Fria Transmontana, is the Montesinho Natural Park (MNP), one of the largest Portuguese nature reserves, with a size of 742,290 m2, and which houses dozens of species of flora and fauna, as well as a cultural heritage with a strong connection to the territory and its people. It covers the northern part of the municipalities of Bragança and Vinhais, bordering the east, north and west with Spain (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Montesinho Natural Park location. Source: author’s compilation based on Official Administrative Map of Portugal (CAOP) and Protected Naturas Areas Network (RNAP).

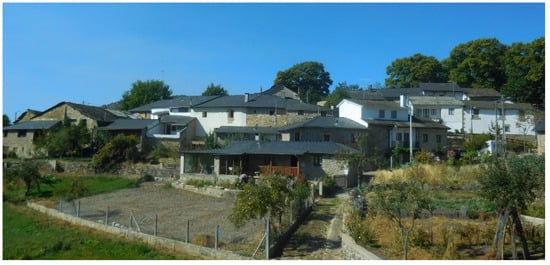

Scattered throughout this territory there are currently about ninety villages that populate its two large massifs—the Serra da Coroa, in the west, and the Serra de Montesinho, in the east. At the top of the latter, we find the village of Montesinho (Figure 2), a rural cluster characterized by the typical houses of the region, with granite walls and porches in wood and blackboard (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Village of Montesinho. Source: image captured by Sofia Matos Silva.

Figure 3.

Typical houses of Montesinho. Source: image captured by Sofia Matos Silva.

The Natural Park is crossed by several rivers, with the Tuela and Sabor rivers having the largest flow. All water lines run from north to south, integrating into the Douro watershed. Soils derived from shales are the most frequent, and among those, the richest are those near the watercourses that are of alluvial and coluvionar origin. The climatic conditions, marked by continentality, present extreme temperatures, being very cold in winter and very hot in summer.

The geographical location combined with its geomorphological configuration, soil diversity and climatic conditions, as well as the human action of the populations that inhabit this region, contribute to the great richness of habitats, both in terms of flora and fauna. There are large patches of oak and chestnut trees, alternating with agricultural land and water meadows (lameiros), or even old forests, now covered by shrubby species (e.g., rush broom) or bushes filled with heather.

The origin of the occupation of this territory is distant in time. It is possible to find archaeological remains of all prehistoric periods to the intense settlement of the Iron Age (1 millennium a.c.), with numerous fortified villages (“castros”—Iron Age hillforts) and their sculptures of “berrões”, representing the fauna of pigs and wild boars that, in the past, were an important food and which, in the present, enrich the region’s gastronomy. The Roman, Germanic and Muslim occupations followed. From the 12th century, the Kingdom of Portugal gradually developed the basis of the current settlement plot.

This humanized territory, in a concentrated settlement of population clusters, built with local raw materials (e.g., shale, granite and oak and chestnut woods) prefigured, through the ages, a unique traditional architecture, although today it is interspersed with a newer one, and associated with the white lofts and mills that maintain the original layout.

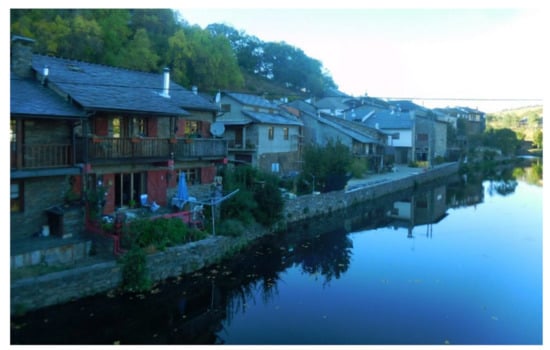

Community life has generated practices that are based on mutual help (e.g., common herds of sheep, goats and even pigs) and the common enjoyment of certain goods and means of production (breeding oxen, mills, forges and bread ovens), whose best-known example is the mill of the village of Rio de Onor, which is currently a tourist attraction (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Rio de Onor. Source: image captured by Sofia Matos Silva.

Often associated with communitarianism, several original and genuine popular festivals take place in the region that are related to ritual practices of integration in adulthood and to the cycles of life and winter solstices, such as the Festas dos Rapazes or Santo Estevão da Lombada feasts. In the summer, the feasts of patron saints animate the villages and promote the meeting of emigrants.

3.2. Demographic and Socioeconomic Trends

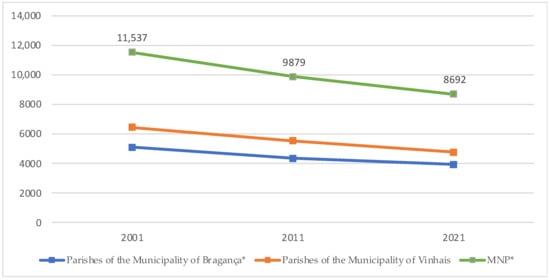

In this region, the demographic trends are similar to other European rural low-density regions, including depopulation, ageing (Figure 5) and the prevalence of a population with low educational levels [2,56,57].

Figure 5.

Ageing in Rio de Onor. Source: image captured by Sofia Matos Silva.

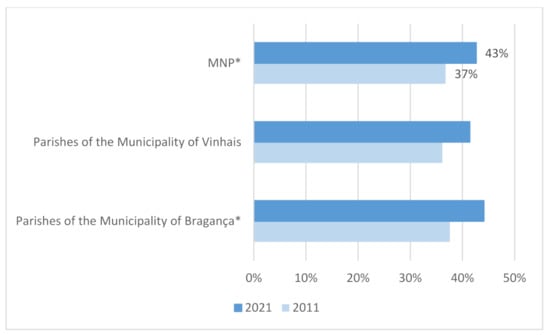

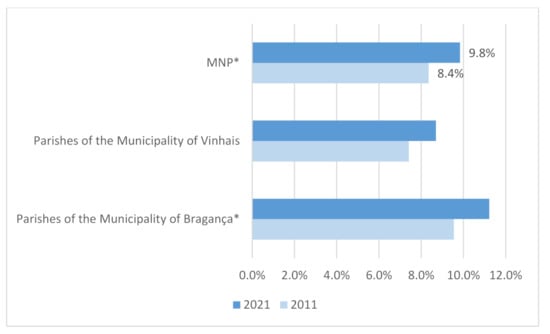

These trends are shown in Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 for the MNP territory. Figure 6 shows a steady drop of the population and a 25% loss of inhabitants between 2001 and 2021. Figure 7 shows the ageing of the population, with a rise of 6 percentage points in the share of inhabitants aged 65 or more years. Figure 8 shows the low proportion of inhabitants with a tertiary education, despite the slight increase in the last decade. Therefore, this is a “deep rural area” [4], where depopulation, ageing and de-skilling are occurring simultaneously.

Figure 6.

Evolution of the population in the MNP region. Source: author’s own elaboration using data sourced from the Portuguese census: Statistics Portugal (INE), Recenseamento da população e habitação—Censos (2001, 2011, 2021). Data are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Tables S1 and S2). * Excluding the parish “União das Freguesias de Sé, Santa Maria e Meixedo”. This parish includes the city centre of Bragança and only a small part of it is included in the territory of the Park.

Figure 7.

Share of the population aged 65 years or over. Source: author’s own elaboration using data sourced from the Portuguese census: Statistics Portugal (INE), Recenseamento da população e habitação—Censos (2011, 2021). Data are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Tables S3 and S4). * Excluding the parish “União das Freguesias de Sé, Santa Maria e Meixedo”. This parish includes the city centre of Bragança and only a small part of it is included in the territory of the Park.

Figure 8.

Share of the population with a tertiary education. Source: author’s own elaboration using data sourced from the Portuguese census: Statistics Portugal (INE), Recenseamento da população e habitação—Censos (2011, 2021). Data are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Tables S5 and S6). * Excluding the parish “União das Freguesias de Sé, Santa Maria e Meixedo”. This parish includes the city centre of Bragança and only a small part of it is included in the territory of the Park.

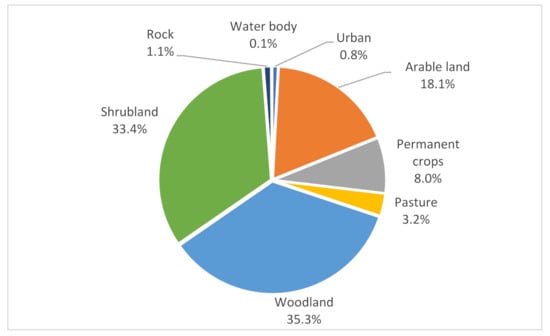

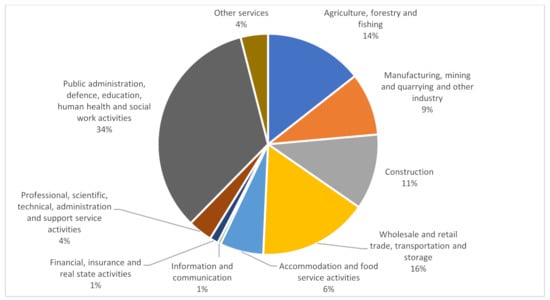

The identity of the inhabitants has a direct relationship with agriculture, one of the main economic activities (Figure 9), which is based on the culture of potatoes, the production of bread (rye and wheat), the exploitation of the chestnut trees and the use of water meadows (lameiros) and uncultivated land linked to livestock activity. Figure 8 shows that the urban land use represents less than 1% of the territory of the MNP, while woodland and shrubland represent almost 70% of that same territory. Nevertheless, according to the statistical data, only 14% of the population is employed in the agriculture and forestry sector (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Land use (ha) in 2018. Source: author’s own elaboration using data from [58].

Figure 10.

Employment of the MNP population by economic activity (2011). Source: author’s own elaboration using data sourced from the Portuguese census: Statistics Portugal (INE), Recenseamento da população e habitação—Censos (2011).

Influxes of new activities following the diversification trend related to multifunctional agricultural systems—mostly linked to gastronomy, handicraft and tourism—and the development of new business models are occurring in the region, mostly related to short supply circuits of food products, eco-certification of agroforestry products and agrotourism.

3.3. Tourism Development in the Region

It is through the Master Plan of the Montesinho Natural Park [59] that the management and the protection of the area is realized. This plan has as its area of intervention part of the municipalities of Bragança and Vinhais (Figure 1), and the intension is to ensure the maintenance and enhancement of the characteristics of natural and semi-natural landscapes and their biodiversity. It establishes measures for the use, management and safeguarding of natural resources and values, as well as for identifying a set of actions and activities to be promoted in the park, allowing its proper enjoyment. Moreover, this plan also identifies forbidden and conditioned activities. It organizes and regulates the land use through three types of areas subject to protection, such as areas of partial protection and complementary protection, for which the scope, objectives and specific provisions are established.

The areas of specific intervention include spaces and sites of relevant natural and cultural interest, which require specific safeguarding and enhancement actions. These areas integrate three typologies: specific intervention areas for the conservation and enhancement of geological heritage (Pedreira de Mármore das Maçãs, Alto da Caroceira concession, Montesinho granite massifs, Rio Frio granites and Serra das Barreiras Brancas); specific intervention areas for the conservation of nature and biodiversity (between Gondesende and Soeira, Espinhosela and Gondesende, Parâmio and Vilarinho, Poiares and Sardoal, Lagomar and Grandais, Oleiros and Donai and Baçal) and, finally, specific intervention areas for the enhancement of cultural heritage, corresponding only to the Roman Mines of France.

As a low-density rural area that maintains some of the traditional rural activities, it is possible to go through the small villages and to listen and learn about the history of this region, and the tales and the superstitions associated with it.

Inside the park, there are several support structures which also nurture knowledge by fostering interest in exploring the region, such as:

- The Interpretation Centre of the Natural Park of Montesinho, installed in the Casa da Vila, a noble residence within the walls of the castle of Vinhais;

- The Interpretation Centre of Autochthonous Breeds in Vinhais Biological Park;

- A mycological centre;

- Several observatories;

- Several hiking trails;

- A viewpoint over the protected area.

According to data provided by the National Register of Tourist Entertainment Agents (RNAAT) and the National Register of Travel Agents and Tourism (RNAVT) of Tourism of Portugal, Bragança integrates about 35% of the 42 tourist entertainment agents (fifteen companies), as well as 43% of the travel agents and tourism companies (nine entities) operating in the sub-region of Terras de Trás-os-Montes [60].

The majority of the tourism animation companies operating in the municipality of Bragança have only been registered since 2010 and promote, mainly, outdoor activities related to nature and adventure and maritime tourism, cultural and landscape tourism and nature tourism activities.

The data provided by INE show that, between 2010 and 2017, hotel establishments registered considerable increases, tripling the number of units, and almost doubling the number of beds available, especially in the northern region and in the sub-region of Bragança.

In Bragança, despite the addition of sixteen hotels, with an extra 419 beds available, the increase in the number of guests and overnight stays is negligible. The total income was also lower than expected due to the increase in supply. In turn, the average number of days of stay in hotels increased by 0.1 days at all territorial levels of analysis.

On the other hand, according to data provided by Tourism of Portugal through the National Tourism Register (RNT) and the Tourism Geographic Information System (SIGTUR), the global supply of tourist resorts in the municipality of Bragança corresponds, currently, to fifty-four tourist resorts, which include: eleven hotels (ten hotels and one pousada), thirty-eight rural tourism resorts (thirty-three country houses, four agrotourism resorts and one rural hotel), two residential tourism resorts and three camping and/or caravan sites. In it is important to stress that most of these establishments are located outside the MNP.

Aiming to enhance traditional products and natural, cultural and landscape heritage resources, the municipality of Bragança includes, in conjunction with neighbouring municipalities (Miranda do Douro, Mogadouro, Vimioso and Vinhais), two thematic routes—the Terra Fria Route and the Chestnut Route. These routes have a set of itineraries that allow the visitor to obtain knowledge regarding the natural and cultural richness of the municipality, as they are associated with the possibility of visiting museums, interpretative centres and museum centres.

As referred in the Evaluation Report on the Implementation of the Municipal Planning of the Municipal Master Plan of Bragança, dated 2020, it is noted that over the past few years, these structures have been the target of significant municipal investments towards their promotion and requalification, highlighting also the construction of the enclosure for the promotion and enhancement of indigenous wildlife.

The economic valorisation of the heritage resources is also verified by the increase in the number of tourism animation companies and travel and tourism agents operating in the municipality of Bragança, most of which have been registered since 2010/2011. These entities carry out, as mentioned above, activities related mainly with nature, the landscape and cultural tourism.

The private investment related to the dynamization and exploitation of endogenous potentialities has also materialised in the increase in the number of tourism enterprises, as well as in the boom of local accommodation, especially since 2014.

However, only a small part of the existing rural agglomerations has experienced an effective increase in competitiveness in these areas. The lack of economic and business dynamism, the closure of health and education facilities, associated with the loss of residents, and the lack of coverage of basic sanitation infrastructure networks, among other factors, have led to the loss of importance of many smaller rural agglomerations [59].

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have naturally also been felt in the decrease in all types of tourism activities, both at the level of the county seat and in the remaining geographical areas of the district, particularly in the area of the Montesinho Natural Park.

Regarding the development of tourism, it is considered that it should be grounded in social inclusion principles. More accessible tourism is not only a social responsibility, but also a way to increase the competitiveness of tourism. Accessible tourism contributes to the social, environmental and economic sustainability of destinations and has positive impacts on the local community [61]. It is, therefore, important to promote the conditions for universal accessibility and inclusion, which are based on the exploration and promotion of its potentialities in terms of heritage [62], geographical potentialities and sustainability.

This should not be limited to physical accessibility, but also, and with special emphasis, on information and communicational accessibility, as well as info-accessibility or virtual accessibility [63], enhancing the visitor’s experience and its meanings.

The promotion of accessible and sustainable tourism in the MNP can be realized through the implementation of organisational innovation by adopting “pioneering services, products and technical processes” ([64], p. 277). This can be achieved through the combination of several tools, namely geographical information systems (GIS) that are an added value for decision-making processes in several areas, including tourism, agriculture and the sustainable management of heritage sites. They provide resource inventories and development models, helping to identify the most suitable locations for development, measure impacts, map relationships between different types of data and produce maps of the tourist destination [65,66,67].

Despite the concern of the Municipality of Bragança with the promotion and dissemination of the brand of the region and the assumption of the need for a more inclusive and accessible tourism, we could not locate the existence of accessible routes or find any attempts to adapt the various places of interest regarding universal accessibility.

Given the little information available on accessible tourism, a brief analysis of the virtual accessibility of the most representative websites was carried out. For this, the automatic validator AccessMonitor version 2.1, developed by the ACCESS Unit of the Foundation for Science and Technology, was used, allowing us to verify the degree of compliance with the recommendations of WCAG 2.0 for the different URLs. This analysis allowed us to know if websites meet the accessibility requirements of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (W3C) of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) (WCAG 2.0), as set out in Directive (EU) 2016/2102 of the European Parliament and European standard EN 17161:2019.

Thus, the website Parque Natural de Montesinho—Visit Bragança (https://turismo.cm-braganca.pt/paisagens-e-biodiversidade/parque-natural-de-montesinho, accessed on 11 November 2021) had an encouraging, albeit insufficient, result of 8.5 (an increase since October 2021, when the value was 6.2) related to compliance with the recommendations of WCAG 2.0. A visit to the website allowed us to verify the existence, though it was not prevalent, of a virtual translation model for several languages of the signs of several walking and mountain biking routes, although there are no references to the type of accessibility related to them.

Another website analysed was the one of the Natural Park of Vinhais (Parque Biológico de Vinhais—Natural.pt). This refers in its website and, in the tab, to “universal accessibility” whereby “The paths of the park are accessible to people with reduced mobility”, revealing the absence of real knowledge of the concept of universal accessibility, which, of course, is not only of a physical character. This finding is confirmed by the web accessibility practices report (WCAG 2.1 of the W3C), with a score of 4.6, which is negative.

4. Analytical Model for Regional Enhancement through Sustainable and Inclusive Tourism and Endogenous Products in Montesinho Natural Park

The analysis, synthesis and interpretation of the literature and the characterization of the territory have enabled us to identify four main inter-related dimensions that need to be included in the analytical model for the design and assessment of the development of Montesinho Natural Park (Figure 11): tourism development, rural development, heritage and collective memory and empowerment of local communities.

Figure 11.

Analytical Model for the development of the MNP. Source: created by authors.

The model draws on the literature on culture and heritage, as well on academic studies on tourism and agroforestry systems, which are increasingly interested in developing new strategies for low-density territories, as mentioned above. It is also aligned with the United Nations’ sustainable development goals (SDGs), considering that it is essential to create innovative strategies, use locally generated resources and promote the employment and quality of life of local communities. Considering the specificities of the territory of Montesinho Natural Park, the proposed model intends to contribute to three SDGs, namely: (8) Decent work and economic growth; (10) Reduce inequalities; (11) Sustainable cities and communities. It advocates for sustainable economic growth through the development and implementation of policies to promote a multidimensional territory, namely, through sustainable and inclusive tourism, enhancing the creation of conditions to promote local culture and products without harming the environment, while allowing people to have stable and decent jobs that stimulate the economy (SDG 8). By promoting universal accessibility and inclusion, it will contribute to SDG 10. Social inequalities stem from multiple conditions, including territorial, gender or age inequalities and social class, resource, educational, political or religion inequalities. SDG 10 focuses on the need to empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, regardless of age, gender, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion, economic condition or other. Tourism, especially in low-density territories, can be a key activity to reduce these inequalities, contributing to higher quality, more inclusive tourism and, actually, to a better society. Finally, it contributes to SDG 11, which advocates and synthesizes the main goals to be achieved with the development of sustainable cities and communities. Accessibility in the territories is one of the priorities of tourism activity. Better inclusivity, with areas accessible to all, makes it possible to achieve the pillar of social sustainability with efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage, with this pillar also based on the improvement of agroforestry activities and, of course, of companies in this sector.

The model suggests that to promote the sustainable development of the Montesinho Natural Park, the new initiatives should be designed and assessed by asking four questions: Is the initiative promoting the rural development of the territory though the creation of synergies between agroforestry and tourism activities? Is the initiative promoting an inclusive and sustainable tourism that is based on the territory’s resources? Are heritage and collective memory being preserved and valued through the initiative? Is the initiative promoting the empowerment of local communities? These questions correspond to the four interrelated dimensions of the model that will be described in the remainder of this section.

As shown above, the Montesinho Natural Park is as a territory with great potential for rural development through the recognition and use of its endogenous characteristics and cultural heritage, namely, ethnographic resources and its involved areas, where natural resources (geology, geomorphology and biodiversity) are included. However, strategies that have been implemented in the territory did not bring, so far, the expected results and, as described above, the region has not been able to reverse the trend towards population loss. Thus, it is necessary to further create innovative dynamics and increase the socio-economic impacts of new business initiatives, namely, in agroforestry and tourism activities and in their interaction, which have a huge potential to foster regional development based on endogenous resources. However, the development of this activities also requires a balance between the environment and economy and the respect for the territory’s heritage. Innovations need to respect and renew traditions, not to eliminate them [29,68].

Tourism development is considered to be central in this process. The model considers that sustainability, inclusion and accessibility in tourism is a goal and a path to pursue in new projects. It is mandatory to consider visitor’s needs, the tourism sector and the communities, as well as its environmental, economic and social impacts, in the present and in the future. The current pandemic crisis offers an opportunity to rethink the positioning of the tourism sector, especially in terms of its relationship with the territory and the communities, respecting the socio-cultural authenticity and ensuring that economic activities are viable in long term. In this way, tourism development in this area should follow the sustainable principles, ensuring the balance between the economic development and the protection of the diversity, ecological and social values of the area, in the same way as that which has been implemented for rural development.

To provide universal access to safe, inclusive, accessible and green public spaces, particularly for women and children, older people and people with disabilities, it is crucial to adopt a non-discriminatory and inclusive type of tourism. Accessible tourism, universal tourism, inclusive tourism and tourism without barriers make it possible to strengthen the competitiveness of businesses, sustainable communities and tourist destinations.

The development of tourism will depend on the heritage and collective memory that make this territory unique. Montesinho Natural Park is a territory that has great potential for development through the recognition and use of its endogenous characteristics and cultural heritage, namely, ethnographic resources and its involved areas, where natural resources (geology, geomorphology and biodiversity) are included. Cultural tourism around cultural heritage and the improvement of agroforestry activities provides the foundations of sustainability to communities. It will also make it possible to improve the territory’s image through various factors, such as the rehabilitation and conservation of heritage. Tourists are increasingly looking for authentic products that reflect their own identity, and which establish a link between the cultural and the natural.

These changes should contribute to the empowerment of local communities. Involving the local communities will raise awareness in the residents concerning the need to protect their heritage and the endogenous resources, which is an added value for the sustainable protection of the region [8,48]. This would promote the commitment and involvement of stakeholders who will act in close coordination, the creation of partnerships between the tourism-related communities and public–private and civil society partnerships and the innovative management of companies and agroforestry activities, alongside the strategic action of regional tourism structures to ensure desirable sustainable, inclusive and accessible tourism based on cultural heritage.

Therefore, the model values the identity, strengths and potential of the region as a multi-sector and multi-purpose rural area [47]. Additionally, this model should be seen in an integrated way and as a whole, in which each dimension is dependent on the others.

These issues, among others that are directly related to the reality of the local communities, should be the focus of solid research, deepening the various themes in order to create sustainability solutions, increase local entrepreneurship and allow for dissemination and promotion based on the assumptions of universal accessibility, also increasing accessible tourism.

5. Concluding Remarks

This paper offers an analytical framework to support the analysis of local development initiatives in a low-density rural territory—Montesinho Natural Park. The analysis of the territory’s dynamics show that it has been subject to a negative socioeconomic evolution, characterized by depopulation and ageing, despite the existence of some efforts to promote tourism in the region and to promote innovation and business opportunities.

However, the analysis also proves that the territory has a rich endogenous resource-base, with emphasis on its landscape and natural resources (geology, geomorphology and biodiversity) and cultural heritage and ethnographic resources. These resources could be leveraged to develop multifunctional systems to attract new businesses and people, while keeping their distinctive traits, as a part of sustainable development.

In order to guide the design and assessment of new initiatives, the model includes four interrelated dimensions: the empowerment of local communities related to capacity building and participation in decision making; the valorisation of the territory’s heritage and collective memory; the development of a sustainable and inclusive tourism strategy; and the promotion of rural development based on innovative sustainable and inclusive business models. Therefore, the model offers a framework for the scrutiny of initiatives grounded on four questions: Does it promote the territory’s rural development though the creation of synergies between agroforestry and tourism activities? Does it promote an inclusive and sustainable tourism that is based on the territory’s resources? Does it preserve and value the territory’s heritage and collective memory? Does it promote the empowerment of local communities?

The application of the model would contribute to an integrated and multidimensional analysis that could be a useful tool to local and regional policymakers, local development associations, tourism entities, environmental groups and business associations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su14074373/s1. Table S1: Resident Population—Bragança Parishes; Table S2: Resident Population—Vinhais Parishe; Table S3: Population aged 65 years or over—Bragança Parishes; Table S4: Population aged 65 years or over—Vinhais Parishes; Table S5: Population with tertiary education—Bragança Parishes; Table S6: Population with tertiary education—Vinhais Parishes.

Author Contributions

This study is a joint work of the authors. Conceptualization, F.M.S., C.S. and H.A.; formal analysis, F.M.S., C.S. and H.A.; investigation, F.M.S., C.S. and H.A.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M.S., C.S. and H.A.; writing—review and editing, F.M.S., C.S. and H.A.; visualization, F.M.S., C.S. and H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article and in the supplementary material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Christmann, G.B. Social entrepreneurs on the periphery: Uncovering emerging pioneers of regional development. disP—Plan. Rev. 2014, 50, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinilla, V.; Sáez, L.A. What do public policies teach us about rural depopulation: The case study of Spain. Eur. Countrys. 2021, 13, 330–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.A.P.D. Fighting depopulation in Portugal: Local and central government policies in times of crisis. Port. J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 17, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinero Hernando, F. Dinámica, discursos, valores y representaciones: La diferenciación del espacio rural. In Espacios Rurales y Retos Demográficos: Una Mirada Desde los Territorios de la Despoblación; Grupo de Didáctica de la Geografía (AGE): Valladolid, Spain, 2021; pp. 7–37. [Google Scholar]

- Molinero Hernando, F. La España Profunda. In Several Authors, Agricultura Familiar en España, Anuario 2017. Agricultura, Desarrollo e Innovación en los Territorios Rurales; Fundación de Estudios Rurales: Madrid, Spain, 2017; pp. 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cañete, J.A.; Navarro, F.; Cejudo, E. Territorially unequal rural development: The cases of the LEADER Initiative and the PRODER Programme in Andalusia (Spain). Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 726–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tödtling, F. Endogenous approaches to local and regional. In Handbook of Local and Regional Development; Pike, A., Rodriguez-Pose, A., Tomaney, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 333–342. [Google Scholar]

- Río-Rama, M.; Maldonado-Erazo, C.; Durán-Sánchez, A.; Álvarez-García, J. Mountain tourism research. A review. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 22, 130–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, C. The EU LEADER programme: Rural development laboratory. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeier, S. Why do social innovations in rural development matter and should they be considered more seriously in rural development research?—Proposal for a stronger focus on social innovations in rural development research. Sociol. Rural. 2012, 52, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, F.; McCann, P.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. The case for regional development intervention: Place-based versus place-neutral approaches. J. Reg. Sci. 2012, 52, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, A.; Baker, K. The socioeconomics of Agriculture. Soc. Econ. Dev. 2010, I, 219. [Google Scholar]

- Renting, H.; Rossing, W.A.H.; Groot, J.C.J.; Van der Ploeg, J.D.; Laurent, C.; Perraud, D.; Van Ittersum, M.K. Exploring multifunctional agriculture. A review of conceptual approaches and prospects for an integrative transitional framework. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, S112–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.A. From ‘weak’ to ‘strong’ multifunctionality: Conceptualising farm-level multifunctional transitional pathways. J. Rural Stud. 2008, 24, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfmann, H.; Markantoni, M.; van Hoven, B. The role of side activities in building rural resilience: The case study of Kiel-Windeweer (The Netherlands). In Regional Resilience, Economy and Society: Globalising Rural Places; Revilla Diez, J., Tamasy, C., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing: Farnham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Recanati, F.; Maughan, C.; Pedrotti, M.; Dembska, K.; Antonelli, M. Assessing the role of CAP for more sustainable and healthier food systems in Europe: A literature review. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 908–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meinhold, K.; Darr, D. Using a multi-stakeholder approach to increase value for traditional agroforestry systems: The case of baobab (Adansonia digitata L.) in Kilifi, Kenya. Agrofor. Syst. 2021, 95, 1343–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanaguli, A.; Kaur, P.; Mazzoleni, A.; Dhir, A. The innovation ecosystem in rural tourism and hospitality—A systematic review of innovation in rural tourism. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.B. Beyond the pillars: Sustainability assessment as a framework for effective integration of social, economic and ecological considerations in significant decision-making. In Tools, Techniques and Approaches for Sustainability: Collected Writings in Environmental Assessment Policy and Management; Sheate, W., Ed.; World Scientific Pub. Co.: Singapore, 2010; pp. 389–410. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, G.; Allain, S.; Bergez, J.; Burger-Leenhardt, D.; Constantin, J.; Duru, M.; Hazard, L.; Id, C.; Lacombe, C.; Magda, D.; et al. How to Address the Sustainability Transition of Farming Systems? A Conceptual Framework to Organize Research. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreiro, M.F.; Sousa, C. Governance, institutions and innovation in rural territories: The case of Coruche innovation network. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2019, 11, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.B. Entrepreneurship as Organizing: Selected Papers of William, B. Gartner; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2016; 400p. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group. Future of Food: Harnessing Digital Technologies to Improve Food System Outcomes; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/31565 (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Pel, B.; Weaver, P.; Dumitru, A.; Haxeltine, A.; O’Riordan, T. Transformative social innovation and (dis)empowerment. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 145, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhurst, N.; Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.; Weaver, P.; Dumitru, A.; Hielscher, S.; Elle, M. Experimenting with alternative economies: Four emergent counter-narratives of urban economic development. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 22, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreiro, M.F.; Sousa, C.; Sheikh, F.A.; Novikova, M. Social innovation and rural territories: Exploring invisible contexts and actors in Portugal and India. J. Rural Stud. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, F.; Labianca, M.; Cejudo, E.; de Rubertis, S.; Salento, A.; Maroto, J.C.; Belliggiano, A. Interpretations of innovation in rural development. The cases of Leader projects in Lecce (Italy) and Granada (Spain) in 2007–2013 period. Eur. Countrys. 2018, 10, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therond, O.; Duru, M.; Roger-Estrade, J.; Richard, G. A new analytical framework of farming system and agriculture model diversities. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 37, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchella, A.; Previtali, P. Circular business models for sustainable development: A “waste is food” restorative ecosystem. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElwee, G.; Smith, R. Classifying the strategic capability of farmers: A segmentation framework. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2012, 4, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šūmane, S.; Kunda, I.; Knickel, K.; Strauss, A.; Tisenkopfs, T.; des Ios Rios, I.; Ashkenazy, A. Local and farmers’ knowledge matters! How integrating informal and formal knowledge enhances sustainable and resilient agriculture. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 59, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, C.; Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J. Entrepreneurs in rural tourism: Do lifestyle motivations contribute to management practices that enhance sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, A.; Teasdale, S. Unlocking the potential of rural social enterprise. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschitz, H.; Roep, D.; Brunori, G.; Tisenkopfs, T. Learning and innovation networks for sustainable agriculture: Processes of co-evolution, joint reflection and facilitation. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2015, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, S.; Jeong, Y.; Kim, S.I.; Milanés, C.B. Why community-based tourism and rural tourism in developing and developed nations are treated differently? A review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H. Can community-based tourism contribute to sustainable development? Evidence from residents’ perceptions of the sustainability. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez, V.A. La teoría del ciclo de vida de los destinos turísticos: El caso de Tandil. Realidad. Tend. Desafíos Tur. (CONDET) 2020, 18, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, S.; Korsgaard, S. Resources and bridging: The role of spatial context in rural entrepreneurship. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2018, 30, 224–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lópes-Sanz, J.M.; Penelas-Leguía, A.; Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, P.; Cuesta-Valiño, P. Sustainable Development and Rural Tourism in Depopulated Areas. Land 2021, 10, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, P.; Baltazar, M.S. Os territórios rurais de baixa densidade como espaço de lazer e de turismo—O Destino turístico Aldeias Históricas de Portugal (Low density rural territories as a leisure and tourism space—the tourism destination Historical Villages of Portugal). Reis 2019, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E. Turismo rural—Reinventar para sustentar? In Reinventar o Turismo Rural em Portugal: Cocriação de Experiências Turísticas Sustentáveis; Kastenholz, E., Eusébio, C., Figueiredo, E., Carneiro, M.J., Lima, J., Eds.; UA Editora: Aveiro, Portugal, 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, N.; Moreira, C. Uncertainty and expectations in Portugal’s tourism activities. Impacts of COVID-19. Res. Glob. 2021, 3, 100071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, J. Turismo Rural. Nuevos Retos Ante la Pandemia del Coronavirus. In El Turismo Después de la Pandemia Global Análisis, Perspectivas y Vías de Recuperación; En, F., Bauzá, J., Melgosa, F.J., Eds.; Asociación Española de Expertos Científicos en Turismo: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. UNWTO Tourism Highlights 2017 Edition; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Garau, C. Perspectives on cultural and sustainable rural tourism in a smart region: The case study of Marmilla in Sardinia (Italy). Sustainability 2015, 7, 6412–6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla, A.; De los Ríos, I.; Salvo, M. Working with People (WWP) in rural development projects: A proposal from Social Learning. Cuad. Desarro. Rural 2013, 10, 131–157. [Google Scholar]

- Acuña, R.; Carmenado, I. Knowledge and Action in Rural Development Planning through Rural Tourism: Ayacucho a Case Study (Buenos Aires, Argentina). Ambiente Desarro. 2018, 22, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, F.; Albuquerque, H.; Sousa, C.; Borges, L. Heritage and accessible tourism in the Côa region: A review of ideas and concepts. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Tourism Research, Universidad Europea, Valencia, Spain, 27–28 March 2020; pp. 268–275. [Google Scholar]

- Alazaizeh, M.M.; Hallo, J.C.; Backman, S.J.; Norman, W.C.; Vogel, M.A. Giving voice to heritage tourists: Indicators of quality for a sustainable heritage experience at Petra, Jordan. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2019, 17, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.; Borges, I. The management of tourism animation in World Heritage destination—Cultural events: St. John’s Festival in Porto and The Harvest Festival in Douro Valley. In Proceedings of the 5th UNESCO UNITWIN 2017 Conference, Coimbra, Portugal, 18–22 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cravidão, F.D.; Cunha, L. Turismo, investimento e impacto ambiental. Cad. Geogr. 1991, 10, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.F.M.; Borges, I. Accessibility on the Ways of Santiago: The Portuguese Central Way. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2019, 7, 62–75. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.F.M.; Borges, I. Digital Accessibility on Institutional Websites of Portuguese Tourism. In Technological Progress, Inequality and Entrepreneurship, Studies on Entrepreneurship, Structural Change and Industrial Dynamics; Ratten, V., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Chapter V; pp. 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Takayama Declaration on the Development of Communities-for-All in Asia and the Pacific—Appendix, UNESCAP Takayama. In Proceedings of the Congress on the Creation of an Inclusive and Accessible Community in Asia and the Pacific 2009, Takayama, Gifu Prefecture, Japan, 24–26 November 2009.

- Darcy, S.; Dickson, T. A Whole-of-Life Approach to Tourism: The Case for Accessible Tourism Experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2009, 16, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolton-Thornton, N. How should policy respond to land abandonment in Europe? Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The future of Food and Farming. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament. 2017; COM (2017) 713 final. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, J.; Castro, M.; Gomez-Sal, A. Changes on the Climatic Edge: Adaptation of and Challenges to Pastoralism in Montesinho (Northern Portugal). Mt. Res. Dev. 2021, 41, R29–R37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICN. Plano de Ordenamento do Parque Natural de Montesinho (POPNM), Estudos de Caracterização 2008; ICN: Bragança, Portugal, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, V.; Dias, R. Relatório de Avaliação da Execução do Planeamento Municipal do Plano Diretor Municipal de Bragança, Município de Bragança 2020. Available online: https://pcgt.dgterritorio.gov.pt/system/files/2020-07-24_rpdmb_fase_1_raepm_revisao.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Silva, M.F.M.; Borges, I. Accessible territories development: Hostels and religious architecture in Portuguese way to Santiago. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Tourism Research—ICTR 2019, Hosted by University Portucalense, Porto, Portugal, 14–15 March 2019; Academic Conferences and Publishing International Limited: Reading, UK, 2019; pp. 308–320. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.F.M. Valorización de los poblados fortificados de la edad del hierro del noroeste de la península ibérica y el turismo arqueológico. In Conserva 2015 20; Centro Nacional de Conservación y Restauración (CNCR) de la Dirección de Bibliotecas, Archivos y Museos de Chile: Santiago, Chile; pp. 23–41. Available online: http://www.cncr.cl/611/articles-57154_archivo_05.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Silva, M.F.M.; Borges, I. Religious Tourism and Pilgrimages in the Central Portuguese Way to Santiago and the Issue of Accessibility. In Handbook of Research on Socio-Economic Impacts of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage; Álvarez-García, J., Rama, M.R., Gómez-Ullate, M., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 375–395. [Google Scholar]

- Blasco Lopez, M.F.; Recuero Virto, N.; Aldas Manzano, J.; Garcia-Madariaga, J. Tourism sustainability in archaeological sites. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 8, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahaire, T.; Elliott-White, M. The application of Geographical Information Systems (GIS) in sustainable tourism planning: A review. J. Sustain. Tour. 1999, 7, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, H.; Martins, F.; Raposo, R.; Cardoso, L.G.; Beça Pereira, P.; Dias, P. Construction of a web-based geographical information system—The case of “Ria de Aveiro” region. Anatolia 2016, 27, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, H.; Costa, C.; Martins, F. The use of Geographical Information Systems for Tourism Marketing purposes in Aveiro region (Portugal). Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreiro, M.F.; Sheikh, F.A.; Reidolf, M.; Sousa, C.; Bhaduri, S. Tradition and Innovation: Between Dynamics and Tensions. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2019, 11, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).