Abstract

Today’s online voting systems pose security concerns and cannot be used for public elections, while offline voting costs significantly more. As a result, a decentralized electronic voting system is emerging, backed by blockchain technology. With blockchain technology applied to online voting, the system can guarantee transparency and confidentiality because individual voter information and aggregate information are stored in a distributed fashion. Due to its decentralized nature, a blockchain-based voting system is more secure than the existing central server-based online voting system. In this study, an Ethereum-based electronic voting system was developed. This system resolves the issue of fraudulent voting by enhancing the safety and reliability of the electronic voting system.

1. Introduction

While information technology has brought about many changes to our daily lives, our democracy requires the adoption of electronic voting to progress further. Centralized electronic voting methods emerged as an alternative to paper voting, resolving the problem of the low voting rate, as voters are not restricted by time or physical location. However, as it is relatively easy to tamper with and manipulate data, the integrity of online voting cannot be guaranteed during the counting process due to arbitrary manipulation or third-party attacks.

At its core, a blockchain-based decentralized form of electronic voting applies distributed ledger technology (DLT) [1]. Every voting participant becomes a member and maintains the integrity of the voting results by possessing one’s voting data and synchronizing them. In other words, the system operates in a way in which voting data do not exist in a centralized repository. Therefore, the system makes it difficult to tamper with and manipulate voting data and prevents invalid or illegal votes, guaranteeing voting integrity and ensuring high reliability [2]. However, this method eventually requires the disclosure of the voting information of all users because it matches users one-to-one with an account address and records the account address and transaction details as a transaction history in the block. Therefore, this method cannot be applied to anonymous voting, as it violates the principle of confidentiality.

Electronic voting is a digitized voting method in which election processes, such as voter registration, voting, and ballot counting, are conducted online [1]. Since voters are not required to visit a specific location to cast a vote, costs can be minimized, and the participation rate can be increased because the system provides greater convenience to voters. Hence, many countries and institutions are paying ever-increasing attention to adopting an electronic voting system. Despite its benefits, the current electronic voting system is rarely adopted in practical use cases due to its security and reliability issues [2].

Therefore, in this study, a blockchain-based online voting system was developed by applying distributed ledger technology as an alternative to the existing server-based online voting system. In this study, the Ethereum platform was selected among the different blockchain technologies, and the voting system was developed using smart contracts based on Solidity, Ethereum’s programming language.

2. Related Studies

2.1. Electronic Voting

Electronic voting is a method of voting through electronic means that replaces traditional paper voting. Paper voting has drawbacks of voters having to go to a designated physical location and the high costs of time and money in printing, transporting, storing, and counting the voting papers. The existing paper voting method causes many problems with respect to fraudulent voting. For example, there are cases where the ballot box has been changed, and there are cases where fake votes have been made using the information of people who did not vote. Electronic voting provides a way to resolve these disadvantages [3]. Anyone can participate in electronic voting either by visiting a designated polling place in person or through an online electronic voting system via a web browser or mobile phone. Electronic voting has the benefits of being cost-efficient as well as not being constrained by time and place. In addition, people with disabilities can participate in voting, and the large-scale voting expenses that occur every year can be reduced. However, electronic voting requires more caution than paper voting because the election process is conducted remotely [4,5,6]. All valid votes must be accurately accounted for in the voting results, and the system must prevent any interference from fraudulent voting attempts. Voters without voting rights must not be allowed to vote, and even if they have the right, the system must ensure that a voter can cast up to only one vote. However, it is not easy to authenticate voters’ real identities and register electronic votes. This poses security issues in tampering with the voting results due to cyberattacks during the voting process. In addition, the confidentiality of voting details and the voters’ personal information may be leaked to third parties. Finally, there is a problem with verification and trust in ensuring the voting results can be checked and validated. Many studies have tried to resolve such known issues of the electronic voting system by conducting theoretical research and analyzing methods to safely perform electronic voting [7]. While technologies such as cryptographic systems, SHA256 encryption, and digital signatures are being utilized in implementing a more secure electronic voting system, research using blockchain technology has only recently begun [8,9]. Therefore, in this study, we designed and implemented a blockchain-based electronic voting system, which is at the domestic research stage.

The Council of Europe, in their recommendations, defined electronic voting as a political election or referendum in which electronic means are used for at least the casting of the votes. It covers a variety of hardware and software solutions that enable voters to vote using information and communication technologies (ICT) such as (i) dedicated electronic voting machines, (ii) optical scanning voting machines, (iii) electronic ballot printers, and (iv) centralized and decentralized software for voting through the Internet. Dedicated electronic voting machines record votes through various input devices, for example, keyboards and touch screens. Usually, they are accompanied by printed copies of the recorded votes, which are called voter-verified audit paper trails (VVAPTs), for verification procedures. The machines provide fast vote collection and counting. Furthermore, they improve ballot presentation and thus reduce the number of spoiled ballots. However, dedicated voting machines are most often created by third parties, making end-to-end verification impossible, which in turn, reduces trust in them. Optical scanning voting machines are used to scan readable paper ballots and record the votes. This solution is easy to understand by common voters and provides fast and accurate results. On the other hand, this solution is dependent on paper ballots that have not been tampered with, which is expensive to deploy and maintain. Electronic ballot printers produce readable paper recipes or voting tokens, which can be disposed of in ballot boxes and processed by counting machines. This method is transparent and verifiable due to the physical evidence of a vote. However, this approach is also expensive, and its only advantage over the traditional voting system is the prevention of ballot spoiling. Centralized and decentralized software for voting through the Internet is an approach to electronic voting that allows voters to cast their votes via devices connected to the Internet. This method can take many different forms, from dedicated devices to dedicated websites. It is convenient for voters to approach voting that can provide fast and accurate results. Unfortunately, this type of voting faces the most numerous security issues, for example, hacker attacks, inadequate anonymity and privacy, and the possibility of coercion. Electronic voting systems can also be classified in regard to two characteristics—(i) remoteness and (ii) supervision.

Remoteness refers to how the votes are transmitted for aggregation and counting. A remote system transfers the votes immediately to a counting authority through some communication channel, for example, the Internet. On the other hand, in a non-remote system, the votes are collected locally and transported to a counting authority after an election. Supervision refers to the voting location. In a supervised system, the votes can be cast only under some kind of oversight by some authority, for example, a polling station. In contrast, a non-supervised system allows voters to vote from any location. Electronic voting is intended to improve the traditional voting process by (i) reducing and preventing fraud through decreasing human involvement, (ii) accelerating result processing, (iii) minimizing costs by reducing voting overhead, and (iv) increasing involvement in democratic processes by using new technologies that increase availability and usefulness. However, electronic voting systems are not without problems of their own. The most common issues faced by such systems include (i) inadequate transparency and understanding of such systems by non-experts, (ii) a lack of standards and norms, (iii) vulnerabilities to attacks and manipulations provided by the system, privileged insiders, and/or malicious users, and (iv) increase in costs due to required ICT infrastructure, energy consumption, and maintenance. Many different approaches use different technologies and algorithms to mitigate these challenges of e-voting. In recent years, blockchain technology has gained much attention, and its potential for improving e-voting solutions has been recognized [10].

2.2. Blockchain

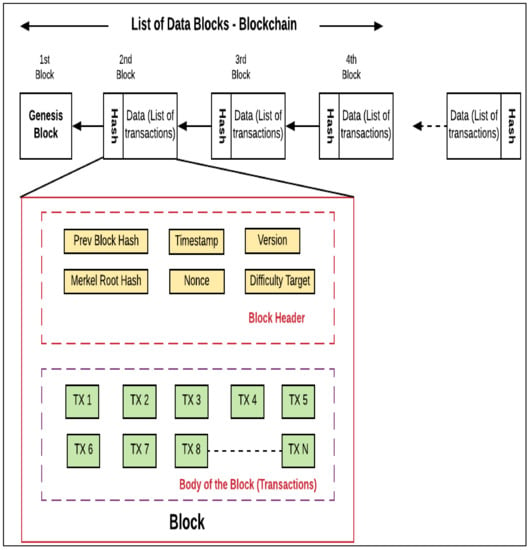

Blockchain, a technology first adopted by Bitcoin in 2008 [11], is a distributed ledger that can store transaction data. A blockchain network requires no trusted central server and can be run in a distributed way. It is open for anyone to participate, and all participants in the distributed P2P network share the same data, verifying transactions according to a consensus mechanism. The data are stored on the blockchain through mining, with miners earning rewards for verifying transactions. As shown in Figure 1, a blockchain consists of linked blocks, where each block is divided into a header and a body. The block header is composed of (i) the protocol version (Version), (ii) the previous block hash value, indicating that the current block is connected to the previous block (Previous Block Hash), (iii) the difficulty required for mining competition (Difficulty), (iv) the time the block was generated (Timestamp), (v) the nonce value used during mining, and (vi) the hash value of the Merkle root, calculated by combining the hash values of each block (Merkle Root). The block body stores the transactions that have occurred.

Figure 1.

Block structure based on blockchain.

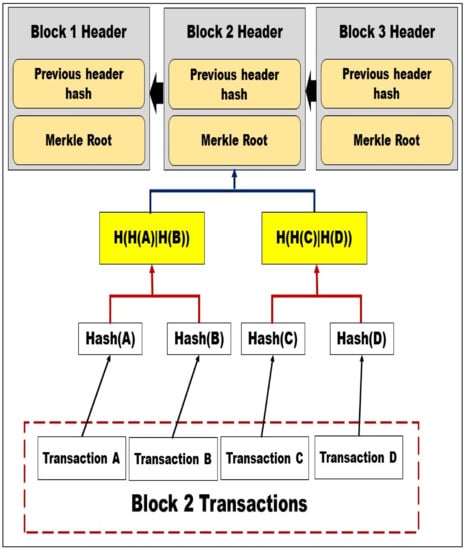

In sum, a blockchain is a linkage of blocks connected in a time sequence that serves as immutable transaction storage. Only new transactions can be added via mining without editing or deleting the existing transaction. Each block contains an encrypted hash value that serves to identify the block uniquely. The identifier is determined by rehashing the block header through the SHA-256 encryption algorithm [12]. As shown in Figure 2, the blocks are composed of Merkle trees [13]. The Merkle tree root is made into a hash to prevent tampering with the transaction details, which are made in the form of a tree. For instance, if we were to make a Merkle tree out of transactions A, B, and C, the results of hashing each transaction datum are first stored in each node. To create a parent node, the 32-byte-sized hash value of the child nodes, transactions A and B, are connected to generate a 64-byte string, which is double-hashed to become the hash of the parent node. In this way, calculations continue until a single node remains on the upper level. When each transaction is made into the form of a binary tree, the last remaining hash value becomes the Merkle hash value.

Figure 2.

Architecture of Merkle tree root.

We can verify the integrity of the transaction through the Merkle hash value in the block and the integrity of the header value through the block hash value. The previously generated block hash value is stored in the next block header’s “Previous Block Hash” item. As the blocks containing transactions are connected sequentially in the blockchain, a new block can be created with the block hash value as a link to the blockchain.

2.3. Smart Contract

Recently, there have been many attempts to extend the application of blockchain technology from data storage to an environment in which to run programs known as smart contracts.

Smart contracts can “integrate the user interface and the protocol” on the network to collectively enforce contract validation and validate contract performance violations based on the consensus protocol and have the properties that guarantee highly secure transactions [14,15]. Recently, many services have emerged based on smart contracts in securities trading, real asset trading, gaming, content, and sharing economies [16]. In addition, many studies are being conducted in the field of guaranteeing system security [17,18]. While in [19], blockchain was assessed to be an appropriate technology for a market scenario with two or more interested stakeholders, and the applicability of blockchain technology to real estate business services was demonstrated, in [20], a voting system using Ethereum blockchain was proposed, and in [21], blockchain was applied to an IoT system. Ethereum is often referred to as the go-to environment for implementing a smart contract. Ethereum is an open platform that generates a smart contract on the blockchain network by transferring data in programming code rather than a currency to execute the code. Ethereum is a blockchain-based platform with a built-in Turing-complete programming language, enabling anyone to write a smart contract and distributed application programs [22]. A smart contract is a source code on the blockchain and can be identified using a unique address. A smart contract is highly similar to the concept of an object in object-oriented programming and includes a series of state variables and executable functions. A newly generated contract does not exist as a document but as an address generated according to an encryption algorithm uploaded to the blockchain address. Then, any participant in the blockchain network can use the contract; when a transaction is sent to the contract, each participating node in the network performs the mining and executes the program [23].

2.4. Case of Blockchain-Based Electronic Voting

(1) Spain

In Spain, a new party, Podemos, has introduced electronic voting using blockchain as a decision-making system within the party. Podemos actively encourages citizen participation and has rapidly grown in the Spanish political circle, with 350,000 party members across the country. All 26 Podemos executives are elected through an electronic voting system using a blockchain called Agora Voting. In addition, through an application called Rumio, a large number of citizens can freely express policy proposals and opinions at any time [24].

(2) United States

Electronic voting using blockchain was used to select the 2016 presidential candidates for the Texas Liberal Party and the Republican Party from Utah in 2016. Because of the convenience that blockchain voting offers, more Utah Republicans than ever before have registered online to cast their votes, Wired reported. Previously, overseas citizens, such as overseas travelers, missionaries, and the US military, had to rely on ballots sent by mail; however, thanks to electronic voting using blockchain technology, the process of registering and conducting voting has been simplified. However, there was also a limitation that only allowed Republican voters to see the voting results [25].

(3) Australia

In Australia, an institution called the Neutral Voting Bloc (NVB) uses blockchain-enabled electronic voting to independently verify voting records and decision-making. Citizens interested in politics can vote online through blockchain and actively register their opinions on policy issues. When the opinion that receives the most votes from the citizens is elected out of various opinions, officials in charge refer to the final tally to determine government issues. The fact that the government decides on issues by actively reflecting on the opinions of the citizens presented the positive implication that blockchain-based voting was well used as a tool to gather the opinions of a large number of citizens [26].

3. Design of Electronic Voting Systems Based on Blockchain

Follow My Vote is a blockchain-based electronic voting system implemented online that uses blockchain to prove to voters and observers that votes have not disappeared from the ballot box. Since the launch of Follow My Vote, Zhao and Chan proposed a Bitcoin lottery-based system. By eliminating the need for a central authority to decrypt the votes after the election period, this new approach does not need to encrypt votes and uses a random number value to hide the voting behavior and the voter’s relationship. It was verified to determine the authenticity of the votes. Most recently, Bistarelli et al. proposed an electronic voting protocol using Bitcoin. This divided the election organization into two entities, one for authentication and the other for token distribution that grants voting rights [27].

The aforementioned Bitcoin blockchain-based electronic voting system could not implement the functions of a complete voting system, such as validating voters and restricting administrative access, due to the Turing-incomplete characteristic of Bitcoin. Instead, the blockchain was partially used. On the other hand, in the case of Ethereum, which supports a Turing-complete language, it was possible to use smart contracts to verify the voters and to implement the entire voting system [28].

In this study, we designed an electronic voting system based on Ethereum blockchain technology. We configured a blockchain network and developed an electronic voting contract (based on Solidity) to facilitate the storage of voting results in a distributed manner. As such, this study resolved the issue of trust and security through distributed storage that maintains consistency in the aggregate voting results [29].

The system consists of five separate modules (USER, CONTRACT, FILE, TRANSACTION, and MAILING). The USER module is categorized into createUser, getUser, login, modifyUser, and deleteUser. The CONTRACT module is categorized into addContract, and findContract. The FILE and MAILING modules are configured alone. The TRANSACTION module is categorized into createTransaction, getSenderTransaction, getRecipientTransaction, and acceptTransaction. In this study, we designed and configured the APIs and models according to each module above [30].

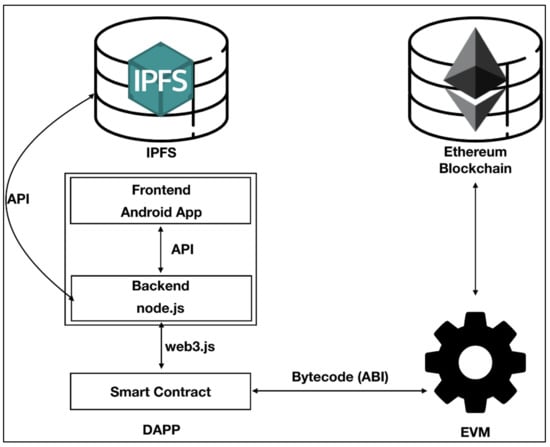

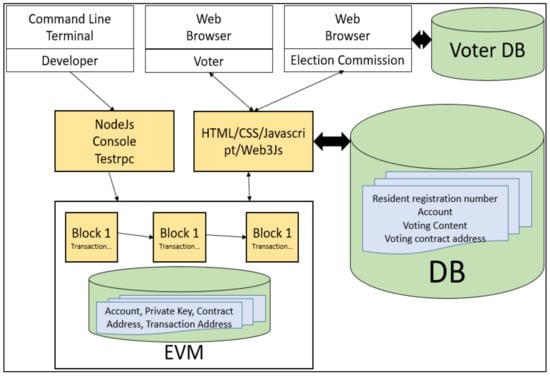

The system configuration uses a blockchain-based Interplanetary File System (IPFS) storage method. Figure 3 indicates the system configuration [31]. This system adopted the node.js server to maximize the system performance and used Ethereum to support a blockchain-based distributed computing network. The blockchain-specific storage system IPFS was used for smart contract document storage and allowed access to the documents based on the application programming interface (API) provided by the IPFS [10]. For transferring documents on the IPFS, web3.Js was used. On an Ethereum virtual machine (EVM), byte code was used to enable mutual transferring between smart contracts. As this system manages contracts via blockchain, it enables the secure and trustworthy management of online contracts. While managing a contract by registering a transaction on this platform does not have the same legal effect as reporting to an institution, managing a contract on this platform can in itself have the effect of notarization. Therefore, using this system can prove that the company makes its contracts transparent to customers who wish to use its services. Moreover, from the customer’s point of view, fraud can be prevented just by signing a contract with a company that manages its contracts in this system.

Figure 3.

System architecture.

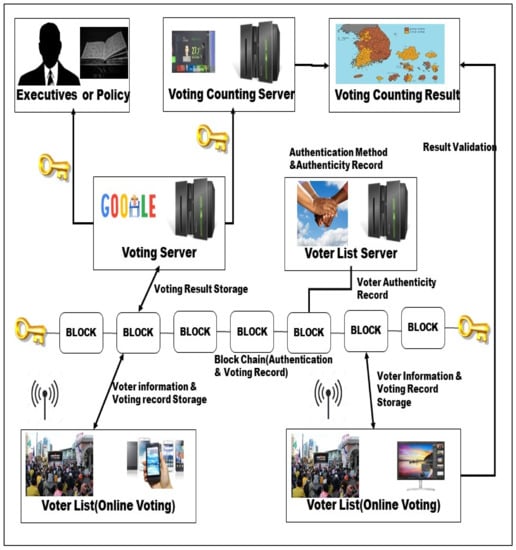

Figure 4 shows a flowchart of a blockchain-based electronic voting system. The block stores voter authentication and voting records, and voters store voter information and voting records through wireless communication. The stored block is safely stored in the block through an encryption key, and voters receive voter confirmation through the voter list server. The authenticated voter transmits the voting result to the voting server, and the recorded information provides the voting result through the voting result server. To build such a stable system, the Election Commission proposes policies, and these policies are stored in the voting server. Each server is stably managed and processed through an encryption key.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of block-based electronic voting system.

- Voting Counting Server: Counts the result of the voter.

- Voting Counting Result: Visualizes and provides the results of the voting counting server.

- Voting Server: Server that determines the voting recorded information of the voter.

- Voter List Server: Server that certifies whether the voter has authority.

- Voter List: Voter performs personal authentication and votes using a smartphone or PC.

- Key: Voter is authenticated through an encryption key when storing information in a block or voting. Information sharing between all servers is activated through an encryption key.

- Block: Stores Ethereum-based voter information.

Step 1. The voter verifies the voter’s identity information in the block of the blockchain.

Step 2. The block information is obtained from the voter list server.

Step 3. When a voter casts a vote, it is stored in a block and the voting result is sent to the voting server.

Step 4. The voting server results are sent to the voting counting server.

Step 5. The voting counting server visualizes the settled result and displays it on the screen.

Figure 5 shows a flowchart of the system configuration diagram. The Ethereum platform was adopted for the development of the blockchain electronic voting system. To test this system, a web page based on Express.js was built. The blockchain was controlled in an RPC-based test net environment, and the linkage between the front-end and the blockchain system was done through the Web3.js module.

Figure 5.

Flowchart of system structure.

4. Implementation of the Electronic Voting System

In this study, we selected the Ethereum platform to develop the blockchain for the electronic voting system. To test this study, we built a webpage based on Express.js. The blockchain was controlled on an RPC-based test net environment, while the front-end and blockchain system integration was conducted via the Web3.js module.

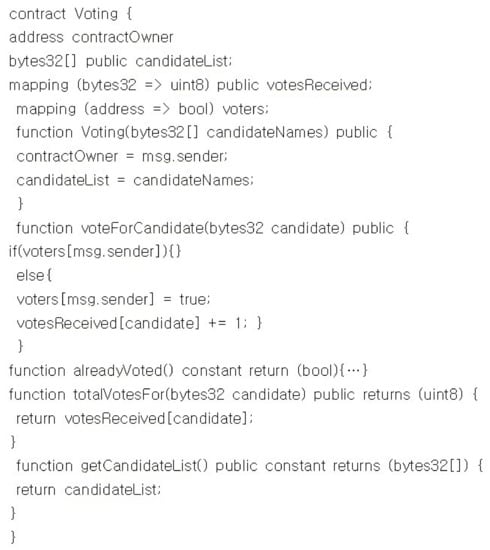

Figure 6 displays a part of the voting source in the smart contract. The task of opening a vote is conducted by deploying a smart contract on the Ethereum blockchain network. A distributed contract consists of a unique contract owner (contractOwner), an array of candidates (candidateList), and the number of votes received per candidate (votesReceived). When a voter casts a vote for a specific candidate in a web browser, the voteForCandidate function of the smart contract is called. The alreadyVoted function determines whether the voter has cast a vote, and the votesReceived value increases according to the result. When the vote ends and the results need to be aggregated, the totalVotes for the function is called.

Figure 6.

Example of smart contract source.

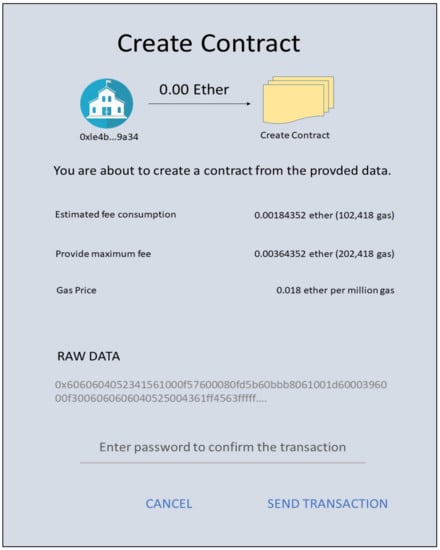

This study proposes a new way to guarantee confidentiality based on a database. This application generates a new account address using the member ID and password that a voter has initially input during the sign-up process. To ensure confidentiality, we encrypted the accounts and stored them in a database along with the member ID values. For encryption, the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) encryption algorithm of the Crypto-js API was used. The AES encryption algorithm is a block cipher using a symmetric key and is widely used worldwide due to its high safety and speed. In this system, the AES encryption algorithm is used in consideration of the safety of the improvement of blockchain-based transaction processing and the prevention of forgery. The encryption key uses a password. The voter can initially sign up and log in to access the system. During login, the stored value in the database is called back and decrypted to obtain the account address, which is set as the session value. During the vote, the session value is set as the transaction’s departure address to proceed with the vote.

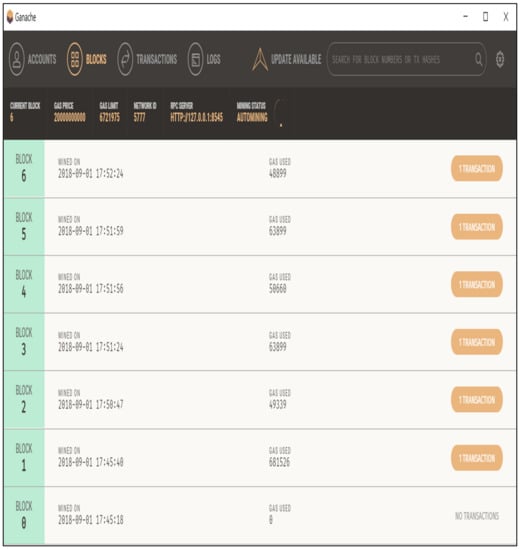

Figure 7 shows the result screen according to the voting procedure. Through voting, a smart contract is generated, which is then stored in a new block. To be stored in a new block, a certain gas fee must be paid.

Figure 7.

Interface of electronic voting result.

Figure 8 indicates the smart contract that was generated from the vote. The functions of an online voting smart contract include voting (vote()), confirming vote (voteClosed()), counting votes (voteCount()), and so forth. When a voter votes, the candidate name must be input into the voter account, whereby the vCount of the voter is counted. To prevent multiple votes from the same voter, the system records the account of a voter who already voted (msg.sender) as true to mark the count. In the contract owned by each account, no more votes can be cast due to the “true” value recorded if the vote was already done (voteClosed()). As a confirmation of the vote count (voteCount()), the system can return the current vote count (vCount) by entering the candidate name. While the study has intentionally made the count status private for visibility purposes, the verification can be made public for confirmation.

Figure 8.

Generated smart contract.

However, there are still problems to be solved in blockchain-based electronic voting. Electronic voting in this system complies with the principle of universal and equal elections but is weak in terms of the principle of direct election. According to the principle of direct election, voters must directly participate in voting activities without going through a third party by giving an authentication code to participate in the election through the voter’s personal information (e-mail, etc.) corresponding to the election. However, it is impossible to check whether the voters themselves participated in the voting activities in a movable place other than the designated place, as the voting activity is out of the control of the monitoring body. In addition, there is a risk of proxy voting due to personal information theft and coercion, as each must participate in voting using their own communication devices.

5. Characteristics and Contributions of the Electronic Voting System

Electronic voting and paper voting methods are technically unreliable and make it difficult to guarantee the principle of secret elections. In this study, we implemented an electronic voting system that safely stores voting details in a blockchain and guarantees the principle of secret elections.

The main characteristic of this method is that it is a network-based distributed system that operates without a central institution acting as an intermediary for transactions. Therefore, all transaction details are open and shared, so traceability is possible and information transparency is maintained. In a system using blockchain, once data or information is included in the blockchain, forgery and tampering are impossible, so the safety of the information is guaranteed. Due to the development of this system, the physical limitation of direct voting, which is difficult for everyone to participate in, has been overcome, and more citizens have participated in policy decision-making. The voting process was simplified, which resulted in a reduction in voting costs. In addition, unlike the existing paper voting system, it is easy to participate anytime, anywhere, so the overall turnout has increased.

(1) Privacy

There is no correlation between the identity of the voter and the address of the blockchain, and in the process of authentication and granting voting rights, the certification body cannot link the identity of the voter with the blockchain address of the voter derived from the random seed. Therefore, the voter’s voting results cannot be tracked, thus protecting the privacy of voters.

(2) Accuracy

The start function of the voting contract can only be executed during the voting period, and only votes cast within the voting period are counted in the blockchain. In addition, if you do not have a token, you cannot participate in voting, and the transfer function used for the token transfer uses two required functions to prevent illegal token transfers to ensure voting accuracy.

(3) Fairness

Voting results can only be viewed after the time defined through the setTime function has passed; if the getCount and getResult functions are executed before the end time, the required function is executed and the contract is terminated. Through this, the fairness of voting is ensured by preventing the leakage of the results of voting by authorized persons.

(4) Eligibility

The addresses of voters who do not have tokens because they are not stored in the contract cannot participate in voting.

(5) Verifiability

Because the contract is distributed through the public blockchain Ethereum, anyone can verify the transaction, and data forgery is difficult due to the characteristics of the blockchain.

(6) Robustness

In the blockchain system, Ethereum miners independently verify blocks, and in the case of a voting system composed of smart contracts included in the blocks, forgery is difficult due to the characteristics of the blockchain. In addition, the voting period can be set only once by the voting manager, and while voting is in progress, the manager cannot perform any actions that may affect the voting system, such as inquiring and changing the voting results through the verification of the voting period.

(7) Safety against soundness, duplicate voting, and forced ticketing

If a person who has already participated in voting through the variable doubleVote wants to vote, the update function that can vote again is executed. This makes it impossible to vote for two candidates, and when re-voting, the number of votes cast for the existing candidate decreases and the number of votes for the newly selected candidate increases. Accordingly, even if a ticket is purchased by force, only the results of the re-voting are reflected in the end. In addition, re-voting attempts are recorded on the blockchain and can be detected through future audits.

(8) Safety of Voting Claims (Receipt Freeness)

By configuring the private key that constitutes the blockchain address so that it cannot be leaked or damaged, the public blockchain address and specific voter information alone do not allow voters to claim that they voted for a candidate.

6. Comparative Analysis

To develop an online voting system based on the Ethereum platform, we implemented an online voting contract and deployed it on the voter’s electronic voting. Table 1 presents a comparison and analysis of the blockchain-based electronic voting system and the existing voting method. Through the implemented Ethereum platform environment and the self-developed online voting contract, this experiment tested whether the role of distributed ledger in a blockchain-based online voting system can guarantee voting credibility. Compared to offline voting, e-voting and blockchain-based e-voting contributed to the improvement of turnout of disabled people and people with reduced mobility. E-voting was able to prevent a drop in voter turnout due to long-distance travel. Election costs can also reduce many incidental costs, including labor costs, compared to the existing paper voting method. A number of previous studies have developed an electronic voting system using Ethereum-based smart contracts, which change the cost per voter according to changes in the Ethereum price and gas price and expand the maximum number of voters due to gas restrictions per block There are gender restrictions [30]. In the case of McCorry et al., assuming that the gas price is fixed at 0.00000002 ether when the price of 1 ether is at the peak of $1100, the cost per voter is close to $73, and the price as of the end of February 2019 If a level of $135 is applied, the cost per voter is $9 [31]. In addition, in order for the blockchain to be operated in a decentralized way, each node must store all votes recorded in the blockchain method. also no Therefore, a proof-of-work consensus algorithm that consumes a lot of energy like Bitcoin and requires economic compensation for block generation when operating a voting system is not suitable. It was developed based on previous research on how to distribute and how to agree, that is, how to generate blocks sequentially so that there is no collision between blocks [30]. In terms of counting errors, the electronic voting method can be manipulated due to the change of mind of the server administrator and by hackers, but this is not possible in the blockchain-based electronic voting method. Finally, the blockchain-based electronic voting method improves voting reliability by making votes practically impossible to manipulate or forge. The cryptographic complexity is higher in Bitcoin-based electronic voting than in Ethereum-based electronic voting, which results in performance degradation. In the existing electronic voting, the encryption complexity is very high, and on the contrary, the encryption complexity is not required for offline voting. In Ethereum-based electronic voting, confidentiality is not required at all, whereas, in other methods, confidentiality is very high. In particular, only the Ethereum-based electronic voting method is very highly extendable compared to the other methods. In the case of extendability, the existing E-Voting system has limited extendability due to the increase in the number of management servers and TTPs(Tactisc, Techniques, Procedures) for the increasing number of voters, resulting in SPoF(Single Point of Failure) and interdependence issues, and in the case of a Bitcoin-based system, separate Bitcoin blocks. Due to the use of cryptographic technology that is not compatible with the chain, all participants need to install a separate program, so there is a limit to the extendability.

Table 1.

Comparison and analysis of other voting methods.

7. Conclusions and Future Challenges

Out of the blockchain technologies, we selected Ethereum upon which to develop an online voting system. A Solidity-based smart contract was implemented and deployed among voters to validate whether the credibility of vote counting can be maintained to develop the online voting system. However, future difficulties may arise in system maintenance because it is impossible to modify a contract once a Solidity-based smart contract is deployed to a blockchain account. In the future, we aim to propose a method to increase the accessibility and maintainability of smart contract development by analyzing the difference between Ethereum’s smart contract programming language—Solidity—and the existing development languages by researching the conversion algorithms among them.

In any voting, it is critical to ensure the confidentiality of the vote content, the credibility of the vote results, and the transparency of the voting process. Such confidentiality, credibility, and transparency factors require a high level of security in the voting system. This program adopted highly secure blockchain technology to develop an online voting system with minimum location constraints to guarantee credibility in the voting process and its results among voters. The study was conducted by applying the most actively adopted mechanism behind cryptocurrency transactions—blockchain technology. The server provides voting coins to the voters; the voters cast their vote using the voting coins and return the coins afterward. The server that receives the voting coins stores the voting results in a database and moves the results to the voting result database. The voters can monitor this entire process on a real-time basis, thereby gaining a high level of credibility in the voting process and its results. Consequently, with a high level of security achieved in the electronic voting system and a high level of credibility in the votes, voters will further trust the idea of online voting. This system will facilitate online voting and encourage voting participation, thereby contributing to higher voter turnout, and enabling a more democratic method of making decisions for our present-day society.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The study did not report any data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cheng, C.H.; Chen, C.H.; Chen, Y.S.; Guo, H.L.; Lin, C.K. Exploring Taiwanese’s smartphone user intention: An integrated model of technology acceptance model and information system successful model. Int. J. Soc. Humanist. Comput. 2019, 3, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yan, J.; Zhou, S.; Li, G.; Bao, J. Application of Blockchain in Carbon Trading. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 4286–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Weber, I.; Staples, M.; Zhu, L.; Bosch, J.; Bass, L.; Pautasso, C.; Rimba, P. A taxonomy of blockchain-based systems for architecture design. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Software Architecture (ICSA), Gothenburg, Sweden, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Q.; Shi, D. Scenario-based potential effects of carbon trading in China: An integrated approach. Appl. Energy 2016, 182, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, S.; Yang, W.; Guo, M. Energy Demand Side Management within micro-grid networks enhanced by blockchain. Appl. Energy 2018, 228, 1385–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, J.; Long, C. Evaluation of peer-to-peer energy sharing mechanisms based on a multiagent simulation framework. Appl. Energy 2018, 222, 993–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorski, J.J.; Haughton, J.; Kraft, M. Blockchain technology in the chemical industry: Machine-to-machine electricity market. Appl. Energy 2017, 195, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Xie, S.; Dai, H.N.; Chen, W.; Chen, X.; Weng, J.; Imran, M. An overview on smart contracts: Challenges, advances and platforms. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 105, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bugday, A.; Ozsoy, A.; Öztaner, S.M.; Sever, H. Creating consensus group using online learning based reputation in blockchain networks. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2019, 59, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, M.; Poniszewska-Marańda, A. Trends in blockchain-based electronic voting systems. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pustišek, M.; Kos, A. Approaches to Front-End IoT Application Development for the Ethereum Blockchain. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 129, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Dong, J.; Wang, K. Graph structure and statistical properties of Ethereum transaction relationships. Inf. Sci. 2019, 492, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Chou, Y.-P.; Chou, Y.-C. An Image Authentication Scheme Using Merkle Tree Mechanisms. Future Internet 2019, 149, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, D.; Zhang, C.; Ping, J.; Yan, Z. Smart contract architecture for decentralized energy trading and management based on blockchains. Energy 2020, 22, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, R.; Lo, A.Y. Emission trading and carbon market performance in Shenzhen. Appl. Energy 2017, 193, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, J.; Xie, D.; Ye, B. Research on China’s cap-and-trade carbon emission trading scheme. Appl. Energy 2016, 178, 902–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaqqi, K.N.; Sikorski, J.J.; Hadinoto, K. Incorporating seller/buyer reputation-based system in blockchain-enabled emission trading application. Appl. Energy 2018, 209, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizamuddin, N.; Salah, K.; Azad, M.A.; Arshad, J.; Rehman, M.H. Decentralized document version control using ethereum blockchain and IPFS. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2019, 76, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, X.; Muhammad, K.; Lloret, J.; Chen, Y.W.; Yuan, S.M. Elastic and cost-effective data carrier architecture for smart contract in blockchain. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 100, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.; Choi, H.; Lee, J. Aerodynamic characteristics of two-bladed H-Darrieus at various solidities and rotating speeds. Energy 2015, 90, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Chung, J.W.; Kim, U.M. A Study On Shared EMR(Electronic Medical Record By BlockChain(Ethereum). In Proceedings of the KIIT Summer Conference, Seoul, Korea, 10–12 December 2017; pp. 436–437. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, Y.S.; Choi, H.S. Changing Business Paradigm and Its Application—Focused on the Block Chain Technology. Korea Sci. Art Forum 2017, 27, 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Kim, C.; Youm, H.Y. Countermeasures against Security Threats to Online Voting Using Distributed Ledger Technology. J. Korea Inst. Inf. Secur. Cryptol. 2017, 27, 1201–1216. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson, E.; Chiesa, A.; Genkin, D.; Tromer, E. Fast reductions from RAMs to delegatablesuccinct constraint satisfaction problems. In Proceedings of the 4th Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science Conference, ITCS ’13, Berkeley, CA, USA, 9–12 January 2013; pp. 401–414. [Google Scholar]

- Valiant, P. Incrementally verifiable computation or proof of knowledge imply time/space efficiency. In Theory of Cryptography; Canetti, R., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-3-540-78524-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson, E.; Chiesa, A.; Tromer, E.; Virza, M. Scalable zero knowledge via cycles of elliptic curves (extended version). In Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 8617. [Google Scholar]

- Bowe, S.; Grigg, J.; Hopwood, D. Halo: Recursive Proof Composition without a Trusted Setup. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2019/1021.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2019).

- He, X.; Alqahtani, S.; Gamble, R. Toward privacy-assured health insurance claims. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Internet of Things (iThings), Halifax, NS, Canada, 30 July–3 August 2018; pp. 1634–1641. [Google Scholar]

- Snchez, D.C. Zero-knowledge proof-of-identity: Sybil-resistant anonymous authentication on permissionless blockchains and incentive compatible strictly dominant cryptocurrencies. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.09093. [Google Scholar]

- Saberi, M.A.; Adda, M.; Mcheick, H. Break-Glass Conceptual Model for Distributed EHR management system based on Blockchain, IPFS and ABAC. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 198, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C. An online voting system based on Ethereum block-chain for enhancing reliability. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2018, 19, 563–570. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).