Abstract

At the intersection of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and human resource management (HRM), a specific research strand has been forming and considerably flourishing over the past years, contributing to the burgeoning academic debate of what has been called “socially responsible human resource management” (SRHRM). The SRHRM debate seeks to proactively enhance employees’ work experiences and meet their personal and social expectations in ethical and socially responsible ways. Despite the increasing interest in research about SRHRM, however, the literature in this area is highly scattered, and a comprehensive study has yet to be undertaken. The present paper addresses this shortcoming by systematically reviewing 57 scholarly articles published in this research domain. It integrates previous insights on the topic to provide a far-reaching theoretical framework that highlights antecedents, practices, and outcomes of SRHRM research. As the results show, between 2011 and 2021, the Sustainability journal has published most of the empirical papers in this area, while the last three years (2019–2021) experienced a significant surge of publications on the topic. Our framework shapes a holistic overview of the SRHRM domain and illuminates different relevant elements upon which future studies in this area could be developed. This contribution is also beneficial for general CSR literature as it stresses the importance of its internal stakeholders, which have been comprehensively given less attention so far. By critically examining the recent literature on SRHRM, we further show how previous research is dominated by studies rooted in utilitarian approaches. Therefore, we set a research agenda for future studies by acknowledging the need for process-oriented studies and the importance of critical scholarship within the field of SRHRM.

1. Introduction

As corporations are an integral part of contemporary society with their operations impacting a wide array of stakeholders, unsurprisingly, the idea of corporate social responsibility (CSR) has been gaining momentum in management research over the last decades [1]. While prior research in this area, not all though, has instrumentally been attempting to find a link between CSR plans and positive financial results for firms [2,3], it has been argued that CSR intentions have gone beyond financial results [4], thereby more actively contributing to solving societal and grand challenges [5,6,7]. Increasing interest in CSR research has partially been rooted in a rationale that considers organizations as critical in reaching a sustainable society [8]. Some authors [9] contended that CSR initiatives are “voluntary” activities of corporations that could bring positive results in different realms of societies. However, this “voluntary” viewpoint is challenged by an intensifying globalization, and one might argue that the strict separation of private and public interests is no longer relevant [10]. Public states even failed in fully serving public and environmental demands to build a sustainable society [11]. Keeping this criticism in mind, Tamvada [12] insisted that CSR could not be seen as an optional provision; rather, it should even be regulated as mandatory obligation of a firm.

The strategic formulation of CSR priorities as well as their translation into everyday managerial practices has however represented a critical challenge for many organizations. As Jamali [13] argued, organizations responded to this challenge by emphasizing the role of human resource management (HRM). Indeed, HRM assumes a critical role as HR activities are highly intertwined with humanistic approaches in organizations [13,14] while contributing to business value creation at the same time [15,16]. It is thus not surprising to see that prior research has considerably sought to relate CSR with HRM [17,18]. The linkage between CSR and HRM can be critical for organizations to, for instance, make sense of the ethical assumptions about their role in societies, improve relationships between themselves and employees [2], and solve the paradoxical tensions (i.e., conflictual interests of different stakeholders) that may occur during CSR initiatives [19].

At the intersection of CSR and HRM, a specific research strand has been forming and considerably flourishing over the last years, contributing to the burgeoning academic debate of what has been called “internal corporate social responsibility” or, as addressed in the present paper, “socially responsible human resource management” (SRHRM) [20,21]. A critical reason for the increasing research interest in this area has been the shortage of insights in CSR literature about its internal stakeholders, i.e., employees [22]. It makes sense to argue that organizations must have a socially responsible approach towards employees, as they will finally implement CSR strategies to responsibly serve external stakeholders. In fact, socially responsible HRM practices could for instance help organizations increase their employees’ ethical awareness and meaningfully motivate them to engage in CSR activities [23].

Finding a universal definition for SRHRM could be a daunting task as this concept is rooted in ethical imperatives and, hence, is highly contextual [24]. We thus hold that SRHRM activities are not merely attempting to provide employees with good working conditions based on legal requirements and regulations (e.g., minimum wage). Instead, they seek to proactively enhance employees’ work experiences and meet their personal and social expectations in ethical and socially responsible ways [25]. Indeed, the SRHRM debate moves the ethical issues concerning employees beyond their instrumental value for organizational aims. It also intends to express deep care for fulfilling organizational members’ personal and professional expectations, thereby genuinely contributing to the employees’ well-being and societal demands [26]. With growing public demands and pressures to shift corporate priorities from mere profitability to responsible and sustainable approaches to management, the HRM field must play a leading role in driving and implementing such plans in practice [27]. To reach this aim, a holistic understanding of the latest advancements in the field could help HRM scholars to more wisely explore current challenges and potential gaps in SRHRM, thereby moving toward a higher level of sustainable management of organizations. Our main aim in the present study is to fill this gap.

Previous research has addressed the role of SRHRM practices in various domains such as “sustainable competitive advantages” [28], “employee citizenship behavior” [29], “talent management” [30], “performance management” [31], “employee well-being” [32], “employees’ turnover intention” [33], “corporate reputation” [34], “affective and organizational commitment” [35], among many others. Despite the increasing research interest in SRHRM, the literature in this area is highly fragmented, and a comprehensive study has yet to be undertaken. Therefore, by doing a systematic review of past robust research in this domain, the present paper seeks to respond to a recent call by Santana et al. [36] for developing a comprehensive framework in SRHRM. To this end, this review integrates the findings of high-impact publications within the SRHRM field to determine, through a multi-level analysis, its antecedents, practices, and outcomes. In addition to depicting a comprehensive theoretical framework in SRHRM, we further aim to explore the research gaps in this area and contribute to the literature by setting an agenda for future research.

More explicitly, the overall contribution of the present systematic review can be explained in three aspects as follows:

- (a)

- It adds to our understanding of the SRHRM domain by analyzing previous literature that has remained understudied thus far [36] and offers a theoretical framework by which future studies in this area could be stimulated. This contribution is of importance for the general CSR literature in reference to internal stakeholders as less attention has been paid to this dimension so far [22];

- (b)

- By critically addressing previous literature and potential gaps in the SRHRM area, the paper suggests a different yet relevant vision for moving this field forward. It calls for a paradigmatic shift from utilitarian approaches to process-oriented studies and critical scholarship within this domain;

- (c)

- It introduces new research contexts and methodologies for future research that have received less attention from previous scholars in SRHRM, thereby opening new realms for the interested scholars to enter.

The rest of the paper is structured in the following manner. Firstly, we explain the review methodology upon which the present study has been conducted. Secondly, we present the bibliometric information of the reviewed articles in terms of journals, publishing years, geographical data coverage, and methods. Thirdly, we categorize the main findings of previous research in three sections, including antecedents, practices, and outcomes at different levels. Fourthly, we present a theoretical framework for SRHRM, discuss the implications of our review, and suggest some potential ideas upon which future studies in this area could be developed. Finally, some concluding remarks end our paper.

2. Research Methodology and Materials

The present research conducts a systematic literature review (SLR) that, by comprehensively studying previously published articles in the SRHRM domain, attempts to determine the antecedents, practices, and outcomes of this research strand. By synthetizing scattered yet interrelated past studies, SLR is indeed a fruitful way to search for and flourish collective insights on a topic, thereby transferring new knowledge into new (sub)fields and realms [37,38]. According to Paul and Criado [39] and Paul et al. [40], SLRs can be classified in various types of reviews such as domain-based (e.g., [41]), theory-based (e.g., [42]), method-based (e.g., [43]), meta-analytical (e.g., [44]), and meta-systematic (e.g., [45]) reviews. Our systematic review falls into the category of domain-based reviews as it seeks to figure out the key variables in relation to a specific research domain, i.e., socially responsible HRM.

As a starting point, we first delineated our research domain, that is, SRHRM, and developed our main research question as follows: “What are the antecedents, practices, and outcomes of SRHRM?” In the next step, our inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined. In so doing, we sought to reach out to the robust empirical papers published in English by academic journals indexed by the Web of Science (WOS) and covered by the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) with impact factor (IF) ≥ 1. We insisted on merely focusing on empirical papers to provide an evidence-driven ground upon which future studies can develop further empirical projects. These inclusion criteria were also consistent with what was suggested by Paul et al. [40]. To identify relevant papers for conducting this review, as suggested by Paul and Criado [39] and Paul et al. [40], we searched our keywords within the two most popular academic databases, including WOS and Scopus. The keywords used for collecting documents include “socially responsible AND human resource management” OR “socially responsible human resource management” OR “socially responsible HRM” OR “SRHRM” OR “SR-HRM” OR “internal corporate social responsibility” OR “internal CSR”. We especially did not include the “CSR AND HRM” keyword in our search process because we sought to be very specific in our research scope, and the CSR-HRM link has already received several systematic reviews thus far [2,18,36].

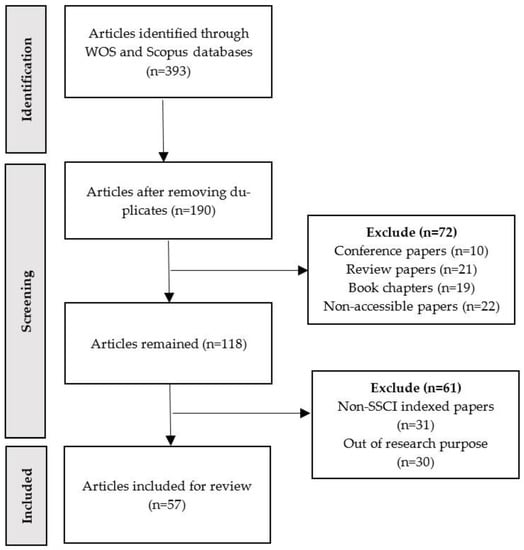

After the initial search within the mentioned databases, we collected 393 documents published from 2011 to the end of November 2021. We chose 2011 as our starting point since the first relevant paper appeared this year according to our inclusion criteria. Subsequently, we removed the duplicates (n = 203), which shortened our list to 190 documents. As with our inclusion criteria, conference papers (n = 10), review papers (n = 21), book chapters (n = 19), and non-accessible documents (n = 22) were excluded from our list. The remained papers (n = 118) were again screened to exclude those papers that did not meet our SSCI criteria, and as a result, a further 31 papers were removed. A careful study of the papers left (n = 87) led us to exclude the papers that were out of our main research scope and purpose (n = 30)—i.e., the papers that were not related to our main question nor concerned with any of the antecedents, practices, and outcomes of SRHRM. As such, our review includes a final list of 57 articles that meet all the inclusion criteria mentioned above. The selected papers for this review were thoroughly addressed and coded in terms of their publishing year, journal, research method, and geographical data coverage. In the next step, we analyzed their findings and thematically categorized them based on the antecedents, practices, and outcomes of SRHRM, similar to what has been conducted by Paul and Benito [46]. Figure 1 shows the article selection process related to the present research.

Figure 1.

The systematic article selection process for the present paper.

3. Results

3.1. Bibliometrics

This section presents the bibliometric information concerning the papers reviewed in the current research. Table 1 shows 26 journals that published empirical research in SRHRM. Accordingly, the Sustainability journal was ranked first by publishing 13 relevant studies in this area, followed by The International Journal of Human Resource Management (n = 7) and Journal of Business Ethics (n = 5) in the second and third ranks, respectively. It seems that these three journals will remain one of the most attractive targets for prospective researchers who wish to publish their studies in SRHRM. The publishing journals come from several academic publishers, including MDPI, Taylor and Francis, Springer, Emerald, Wiley, Elsevier, and Sage. The journals’ scope that published research in this domain is varied, including business ethics, environmental sciences, CSR, HRM, public health, strategic management, to name but a few. The varieties of the journals indicate the interdisciplinary nature of the SRHRM research field, which is connected with, and can have critical implications for, a wide array of issues in societies.

Table 1.

Journals that published empirical research in SRHRM.

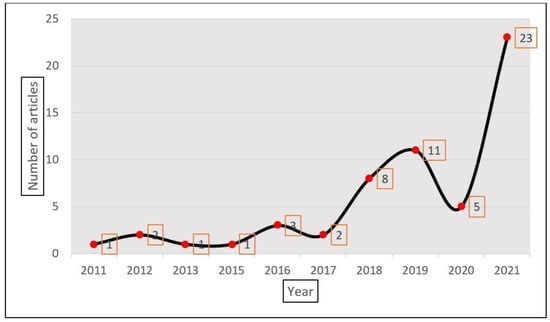

Figure 2 represents the distribution of studies in SRHRM research published from 2011 to 2021. Interestingly, the number of publications in this area received a sharp surge in 2021 (n = 21), making it the most prolific year over the last decade. As depicted in Figure 2, the number of publications from 2011 to 2017 was often the same (i.e., between one or two papers) in this area. However, SRHRM gained momentum in 2018 (n = 8) and culminated in 2021 with 23 published papers until November. Considering the appearance of the Covid19 pandemic and numerous challenges HRM practitioners face [102,103,104,105], we expect the publishing rate in the field of SRHRM to rise considerably in the coming years.

Figure 2.

Distribution of studies in SRHRM across years.

Table 2 shows the distribution of papers published in the SRHRM domain based on geographical data coverage. Most published articles pertain to China (n = 15), followed by Spain (n = 13) in the second rank. Five papers did not limit themselves to specific countries; instead, they simultaneously addressed SRHRM within several countries. As shown by Table 2, the countries covered by the empirical data gathered in previous papers come from different continents worldwide, including Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, and Africa. According to the increasing interest in the SRHRM research over the last years, it is predicted that future empirical studies will cover more countries, thereby providing cross-cultural data for better understanding the contingencies that may exist within different national contexts.

Table 2.

Distribution of studies on SRHRM across countries based on geographical data coverage.

Table 3 categorizes the previous studies in SRHRM based on research approaches and methods. Most published papers employed a quantitative approach (n = 44) and tested previous scholars’ research models [20,21,94]. Qualitative (n = 7) and mixed (n = 6) approaches were also used in this field, though their size is not very significant compared to the quantitative studies. The proliferation of quantitative studies provides an excellent ground upon which to generalize the findings in the SRHRM domain, while the shortage of qualitative studies in this area signals a significant void to gain a more in-depth understanding of SRHRM dynamics and processes. We will reflect more deeply on it in the discussion section.

Table 3.

Distribution of studies in SRHRM based on research methods.

3.2. Antecedents of SRHRM

This section determines the factors affecting and driving the adoption and implementation of SRHRM practices in organizations. In this way, we categorized the antecedents into three groups, including external, firm-level, and individual-level factors. Concerning external factors, previous studies mentioned different items that could have an impact on the SRHRM practices, such as laws and regulations [21,62,66,100], public demand and expectations [61,64,92], market pressures induced by, for example, competitors and/or customers [26,53,74], union pressures such as those coming from the International Labour Organization (ILO) [48,62,66], the national institutional context [78,89], and external crisis, such as what all organizations experienced due to the COVID-19 pandemic since its appearance in 2019 [72,76]. The second group of antecedents pertains to the firm-level factors. Although all the reviewed papers assert that CSR firm policies impact SRHRM practices, some studies also explored other drivers within firms that might have been influential in this regard. Such factors include firms’ strategic policies and priorities [48,60], available financial resources [60], HRM systems design [60], HRM power in the organization [26], ethics-oriented HRM philosophies [65], the multi-nationality of firms [93], as well as organizational structure and culture [80]. The third antecedent category is related to the individual factors, including employees’ needs and wants [21,62,77,79], the presence of an ethical leader [60,61,75,89,92,101], the HR professionals’ perception of their ethical role [61], and the role of employees’ representatives in organizations [56].

3.3. Practices in SRHRM

This section addresses the practices in SRHRM that have been considered by previous studies. As most of the studies in the reviewed papers were conducted by applying quantitative methods, as shown in Table 3, they more or less employed the same framework developed by Shen and Benson [94], Shen and Jiuhua Zhu [21], and Orlitzky and Swanson [20]. SRHRM practices were mostly adapted from the traditional HRM functions (i.e., recruitment and selection, training and development, working conditions, appraisal and reward) by including ethical and fairness issues such as the consideration of work-life balance through, for example, flexible working time (e.g., [63]), enhanced communication at work (e.g., [62]), safety and health at work (e.g., [49]), transparent criteria in recruitment and selection (e.g., [54]), equal opportunities (e.g., [53]), fair appraisal processes (e.g., [78]), training opportunities and different personal development alternatives such as employee participation in decision-making (e.g., [86]), as well as providing additional support for employee education [83]. However, some studies that emphasize specific practices, less addressed by previously structured frameworks, are worth mentioning. In this vein, Shan et al. [100] call for considering sexual minorities to make the workplace diverse, Lombardi et al. [71] recommend embracing more extended work contracts to make the job more secure for the employees, and Obrad and Gherheș [47] note that facilities for people with disabilities and also for remote working should be provided. Moreover, Celma et al. [82] and Lin-Hi et al. [79] insist on devising non-discrimination policies at the workplace, and some studies hold that a context for social dialogue between employees and managers needs to be built [70,81,96,97,98].

3.4. Outcomes of SRHRM

In this part, we report the outcomes of SRHRM as found by previous studies. At the macro level, Bombiak and Marciniuk-Kluska [50] assert that SRHRM practices provide a path for the sustainable development of organizations, which finally result in increasing societal well-being [78] and the building of a sustainable, responsible, and ethical society [53]. Concerning the firm-level outcomes, evidence shows that SRHRM practices could increase financial and non-financial firm performance [66,81,86,95,96], already achieved CSR firm results [86], intellectual capital [70], firm reputation [55,90], and even firm innovation [90]. Furthermore, Low and Bu [87] suggest that SRHRM practices can help the organization to implement the digitalization of work processes more committedly, while Parkes and Davis [61] contend that organizations could more quickly attract talents by employing SRHRM strategies.

Individual outcomes of SRHRM practices have been the most topical issue addressed by previous studies. In this regard, a considerable number of studies confirmed that SRHRM can have a positive impact on employee commitment [21,49,63,66,78,83,87,95,97]. Other individual factors positively affected by SRHRM practices include employee citizenship behavior [51,55,62,66,83,84,92], employee task performance [59,94], employee satisfaction [72,81,95], employee well-being [68,78], employee loyalty [101], the propensity of employees to identify themselves with their organization [59,83,88,89,91], employee–employer relationships [79,84], employee trust in the firm [72,74,76], employee empathy [52], employee knowledge sharing behavior [74], employee innovation behavior [54,99], and employee intrapreneurial behavior [96,98,99]. It has also been shown that SRHRM practices can help employees to make sense of their jobs in a meaningful way [75] and even make employees more resilient in times of crisis, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic [76]. Further positive outcomes include increasing employee advocacy behavior within social media platforms [84] and enhancing the person–organization fit [69]. Using SRHRM practices, organizations can also decrease employees’ intention to leave their organizations [55,77].

4. Discussion and Future Directions

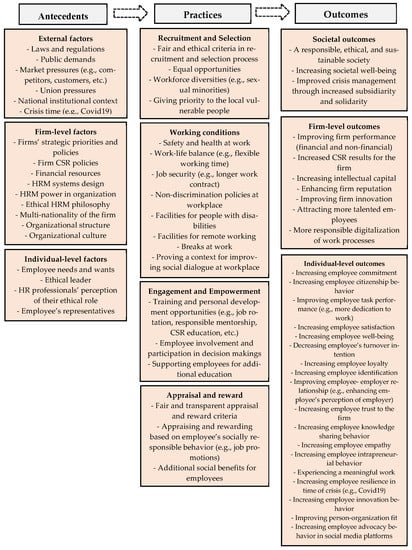

By conducting a comprehensive study of the selected empirical articles published from 2011 to 2021, the present paper has analyzed the current state of knowledge in SRHRM. The results of the reviewed articles can be categorized into three sections, including the antecedents, practices, and outcomes of SRHRM, as Figure 3 shows. We have provided insights concerning antecedents and outcomes of SRHRM from different levels of analysis, including societal-, firm-, and individual-level analyses. Regarding SRHRM practices, we have presented four critical domains, including recruitment and selection, working conditions, engagement and empowerment, and appraisal and reward. Figure 3 thus presents a new, comprehensive framework within which the antecedents, practices, and outcomes of SRHRM are combined and related to each other. By integrating previous literature that was scattered thus far [36], the introduced framework has shaped a holistic overview of the SRHRM domain and presented different relevant elements upon which future studies in this area could develop novel research projects. This contribution is also vital for general CSR literature regarding its internal stakeholders as less attention has been paid to this dimension until now [22]. While our framework provides a collective insight into the state of the art in the field of SRHRM, it barely suggests new pathways regarding what future studies should explore and investigate. Hence, by critically addressing the current research gaps and delineating potential research opportunities in the SRHRM area, the paper depicts a different yet relevant vision for developing this field in the future. It calls for a paradigmatic shift from utilitarian to critical and humanistic management approaches and process-oriented studies within this domain. This very landscape could stimulate future studies to embrace the “provoking” mode of theorization [106] on SRHRM in which the taken-for-granted concepts are challenged, and hidden sides of already presumed realities might be unraveled. In the next section, we will reflect on and bring new insights into this critical and paradigmatical shift more in detail.

Figure 3.

SRHRM theoretical framework based on the reviewed articles.

4.1. Implications for Theory

Critically examining previous SRHRM research, we concede that most of the articles reviewed in this paper are rooted in utilitarian ideologies [107], seeking to find out how HR practitioners might get different yet “positive” results through socially responsible management of people within firms. The domination of studies based on utilitarian approaches could be problematic in the development of SRHRM research. According to Dale [108] and Greenwood [109], these approaches treat employees as the “dish of the day” being consumed, even though in a socially responsible manner, by the employers. One of the common assumptions behind such utilitarian studies is that there are no conflictual interests between employers and employees, all attempting to serve a common end harmoniously. However, there are some exceptions in the papers we reviewed. Some authors [60,61,65] do unveil how conflictual interests between employees, managers, and employers could compromise SRHRM and even drag it into “irresponsible” terrains, see also Voegtlin and Greenwood [2]. Thus, future researchers will need to focus more on the political role and the power dynamics at play in SRHRM, as suggested by Sarvaiya and Arrowsmith in one of our reviewed articles [85]. This criticism by no means argues that the utilitarian approaches should be divested. Instead, it insists on the crucial role that a pluralistic and multidisciplinary approach in the chosen research methodology can play to make the theoretical development in the HRM field more constructive [110,111,112]. For instance, if we consider with Hegel [113] and Durkheim [114] that the labor market is not only a means to increase efficiency but also a means for social integration, then we acknowledge that the market is part of our social life and its functions depend from the satisfaction of moral promises such as those of quality and meaningful work that can transparently be related with the work of others [115]. This philosophical perspective highlights, and thus helps us to understand, that capitalism works only if two conditions are satisfied: (a) the independence of all economic actors, including workers, is ensured by appropriate salaries, and (b) work is not only meaningful but its contribution to the common goal can be identified and recognized by the others. Fairness and transparency in the division of labor and in working conditions are the premises for developing a sense of social belonging as well as solidarity among workers, and thus the necessary social integration to ensure the pacific development of capitalism. Within this context, the political role that SRHRM can play to accompany and enhance this development is evident.

One of the reasons why the utilitarian approaches dominate previous research is perhaps related to the way scholars looked at the nature and functions of HRM. Explicitly, most of the reviewed papers understand HRM in its utilitarian, even though ethical, definition that is prevalent in the main HRM textbooks, such as “the process of acquiring, training, appraising, and compensating employees, and of attending to their labor relations, health and safety, and fairness concerns” [116]. Critical HRM scholars criticized this viewpoint as it offers a depoliticized and simplified understanding of HRM [117]. To tackle this challenge, we note that other researchers have also offered alternative conceptualizations of HRM. In this respect, we draw future scholars’ attention to a comprehensive definition that explains HRM as “institutions, discourses and practices focused on the management of people within an employment relationship enacted through networks comprising multiple public and private actors” [2]. We strongly believe that such a definition can broaden the future research scope in the field of HRM and encourage researchers to consider a multi-level analysis addressing different issues through the lenses of both micro and macro frameworks. This definition does not consider HRM as a linear order of practical functions within the borders of organizations but rather as a network of multiple (i.e., internal and external) actors and institutions, which calls for more engaged and coordinated scholarship and practice in different realms. The HRM field gains this way more importance and assumes more responsibilities within the management field. Based on this definition, SRHRM will be able to offer more holistic insights by considering how different institutions and stakeholders can shape the trajectories of future research in the field.

To engage more committedly in critically addressing the political dimensions of SRHRM, future researchers need to equip themselves with some holistic frameworks that allow them to connect firm-related issues with the political, economic, and social factors shaping the ways companies operate. To this end, we strongly recommend that future researchers consider the labor process theory (LPT) [118,119]. LPT is a Marxist approach asserting that the capitalistic mode of production, which seeks to increase capital accumulation, has been steering the ways workers are managed, disciplined, and evaluated in modern companies. The primary rationale behind the LPT is that the managerial apparatus aims to separate workers from their holistic knowledge to make their work cheaper by, for example, splitting the work processes into smaller and more superficial elements. The other underlying idea is how workers are controlled to primarily serve employers’ interests at the expense of a degraded nature of work as workers experience it. Literature in the LPT has much progressed over the last decades and shows, for instance, how “lean production” initiatives [120], “knowledge management” [121], and “performance management” systems [122], are employed to induce more pressure on workers, thereby achieving more “desirable” results for the employers. The LPT has also been more recently applied in the age of digital technologies, to analyze and understand algorithmic control in the workplace [123] and workers’ algorithmic management in the sharing and gig economies [124,125]. Therefore, by conducting a cross-level analysis, as suggested by Shao et al. [51], and employing the LPT framework in the SRHRM research, we firmly believe that future researchers can open new venues in which fresh insights about, for example, socially responsible control mechanisms, work design approaches, and agency-enabled work organizations could be attained to reach a humanistic type of management and capitalism [112]. A consideration of the dynamic role of business imperatives in shaping ethical HR practices is also suggested by one of the articles reviewed in this research [26]. LPT also offers many potentialities to link SRHRM research with the political CSR approach, see [2], which conceives the role of corporations not just for profit-making but rather as political actors that can proactively play a responsible role in defining the standards for treating employees in a socially responsible manner [7,10,11].

The other theoretical implication that we can draw from past SRHRM research pertains to its “static” position toward different workplace issues. More simply, most of the articles reviewed in this research focused on the content of SRHRM and sought to find antecedents, practices, or outcomes related to the SRHRM domain. While we clearly recognize the contributions of such studies for improving our understanding of the SRHRM phenomenon, we call for a “processual turn” and recommend future research to consider process-oriented approaches in organization studies [126] for shedding light on the “social construction” of SRHRM practices in the workplace. By emphasizing the need for process-oriented studies, we intend to draw researchers’ attention to the dynamics that may exist in the SRHRM practices. To reach this aim, prospect scholars may consider the application of process thinking abilities to enrich their cognitive skills in recognizing movements, events, and changes concerning the given phenomenon [127]. If we consider the nature of organizations as “ongoing world-making phenomena” [128], it is then arguable that each reality relating to organizations could or even should be understood as a process and problematized as an evolving phenomenon. We thus invite interested scholars to investigate the processual nature of SRHRM, for instance by asking and reflecting on how, why, and when specific practices emerge and grow within the SRHRM debate over time [129]. In this respect, future researchers may benefit from some process-based theories that have been influencing previous HRM research, such as “sensemaking theory” [130,131], “strategy-as-practice theory” [132,133], and “dynamic capabilities theory” [134].

4.2. Implications for Context and Method

While previous literature in the SRHRM domain has provided valuable insights into different contexts, including service sectors [69], public organizations [91], manufacturing companies [94], and educational institutions [58], there is still insufficient knowledge about the state of SRHRM practices in platform-mediated business organizations. Considering the disruptions that these new online companies brought to the traditional HR functions [135,136], it is thus a crucial area that needs to be addressed by future studies. We believe that platform-mediated work presents specificities [137,138,139,140], which make it significantly different from other types of work and allow for unique power structures among various actors to develop [141]. This calls for special attention on this very topic. As such, we encourage prospective researchers to address the challenges for devising and implementing SRHRM practices consistent with the nature and specificities of such platform-based companies. This may have substantial implications for the optimization of resources and thus the sustainability of those companies [142].

Another context in which SRHRM is rather unexplored is related to the media and cultural industries [143,144]. Indeed, the success of the products created by these industries is highly dependent on the professionals’ innovation capability [145,146,147], creativity [148,149], emotions [150], reputation [151], and entrepreneurial orientations [152,153,154,155]. It is also reported that media professionals often have project-based careers [156] and, hence, experience their occupations as highly precarious [157,158]. Another exciting feature of media and cultural industries is that their products do not merely include economic value [159,160,161]. Instead, they could affect people’s understanding of different societal issues connecting media organizations with a wide array of social and political affairs and actors [162,163]. Thus, considering the social value of media and cultural work, we recommend that future studies develop novel theories and conceptualizations concerning how social responsibility could guide the sustainable management of creative professionals in the media and cultural industries, as well as the drivers of and barriers to the successful implementation of SRHRM practices within organizations in those industries.

Regarding the methodological implications, and according to the reviewed articles in the present paper, it appears that future research would highly benefit from employing ethnographic methods [61], longitudinal studies [59,88,94,98], comparative and cross-cultural research [67,80,83,85], experimental research design [57], and data collecting from different sources [84,87], specifically relying more on the employees rather than senior managers’ perspectives [47,48]. However, these methodological recommendations mostly come from those quantitative studies that originated from utilitarian philosophies. To reach the paradigmatic shift and critical standpoint in this area, as suggested in this paper, we thus recommend that future researchers consider different points of view to analyze organizational and workplace realities, which requires greater attention to the ontological, epistemological, and methodological imperatives related to each paradigm. In this way, we encourage future researchers to embrace different paradigmatic alternatives such as radical structuralism and/or radical humanism in organizational analysis, as for instance explained by Burrell and Morgan [164].

4.3. Research Limitations

While we did our best to cover all major research conducted in the SRHRM domain, there are still some chances that we may have missed some articles. In addition, just like other SLRs, we had to limit our inclusion criteria and, as such, merely empirical articles (covered by SSCI in WOS) with IF more than 1 were included. To cope with these limitations, we encourage future scholars to broaden their inclusion criteria and embrace other non-empirical documents such as book chapters and conceptual articles to shape a more comprehensive picture of SRHRM.

5. Conclusions

In the present review, we have integrated the recent literature on SRHRM and presented a comprehensive theoretical framework to shed light on the antecedents, practices, and outcomes related to this research area. To this end, we have reviewed 57 scholarly articles published in high-quality journals from 2011 to 2021. Based on the results, it is reported that the Sustainability journal has published most articles on SRHRM, and the number of publications has considerably increased in this area during recent years. We have also shown how utilitarian approaches dominate the SRHRM research. To embrace more theoretical pluralism in this domain, as also suggested by Pirson [112], we have encouraged future studies to consider a processual turn and adopt critical as well as multidisciplinary perspectives within this area. Therefore, the present paper has contributed to the burgeoning literature on SRHRM by analyzing and integrating the current knowledge in this domain and setting a research agenda to stimulate future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.O. and C.D.Z.; methodology, A.O. and C.D.Z.; data curation, A.O.; writing—original draft preparation, A.O.; writing—review and editing, A.O. and C.D.Z.; visualization, A.O.; supervision, C.D.Z.; project administration, C.D.Z.; funding acquisition, C.D.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What We Know and Don’t Know About Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegtlin, C.; Greenwood, M. Corporate social responsibility and human resource management: A systematic review and conceptual analysis. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2016, 26, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G.; Baumann, D. Global Rules and Private Actors: Toward a New Role of the Transnational Corporation in Global Governance. Bus. Ethics Q. 2006, 16, 505–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulcanaza-Prieto, A.B.; Shin, H.; Lee, Y.; Lee, C. Relationship among CSR Initiatives and Financial and Non-Financial Corporate Performance in the Ecuadorian Banking Environment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. On Corporate Social Responsibility, Sensemaking, and the Search for Meaningfulness Through Work. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 1057–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tong, L.; Takeuchi, R.; George, G. Corporate Social Responsibility: An Overview and New Research Directions. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G. Toward a political conception of corporate responsibility: Business and society seen from a habermasian perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 1096–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, M.; Adams, M.; Walker, T.R.; Magnan, G. How corporate social responsibility can be integrated into corporate sustainability: A theoretical review of their relationships. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2018, 25, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanji, G.K.; Chopra, P.K. Corporate social responsibility in a global economy. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2010, 21, 119–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G. The New Political Role of Business in a Globalized World: A Review of a New Perspective on CSR and its Implications for the Firm, Governance, and Democracy. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 899–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G.; Matten, D. The Business Firm as a Political Actor. Bus. Soc. 2014, 53, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamvada, M. Corporate social responsibility and accountability: A new theoretical foundation for regulating CSR. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2020, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; El Dirani, A.M.; Harwood, I.A. Exploring human resource management roles in corporate social responsibility: The CSR-HRM co-creation model. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2015, 24, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, M.; Salamzadeh, Y.; Loke, C.K. Can ethical leaders drive employees’ CSR engagement? Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 16, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantele, S. Human resources management in responsible small businesses: Why, how and for what? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2018, 18, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Zotto, C.; Gustafsson, V. Human resource management as an entrepreneurial tool. In International Handbook of Entrepreneurship and HRM; Barrett, R., Mayson, S., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2008; pp. 89–110. [Google Scholar]

- Sarvaiya, H.; Eweje, G.; Arrowsmith, J. The Roles of HRM in CSR: Strategic Partnership or Operational Support? J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 153, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgorodnichenko, N.; Edgar, F.; Akmal, A. An integrative literature review of the CSR-HRM nexus: Learning from research-practice gaps. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2021, 100839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgorodnichenko, N.; Edgar, F.; McAndrew, I. The role of HRM in developing sustainable organizations: Contemporary challenges and contradictions. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Swanson, D.L. Socially Responsible Human Resource Management: Charting New Territory. In Human Resource Management Ethics; Deckop, J.R., Ed.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2006; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Jiuhua Zhu, C. Effects of socially responsible human resource management on employee organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 3020–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frynas, J.G.; Yamahaki, C. Corporate social responsibility: Review and roadmap of theoretical perspectives. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2016, 25, 258–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Cheng, J.; Chen, Q. Socially responsible human resource management and employee ethical voice: Roles of employee ethical and organizational identification. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lähteenmäki, S.; Laiho, M. Global HRM and the dilemma of competing stakeholder interests. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greige Frangieh, C.; Khayr Yaacoub, H. Socially responsible human resource practices: Disclosures of the world’s best multinational workplaces. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen, S.; Lämsä, A.-M.; Niemistö, C. Work–Family Practices and Complexity of Their Usage: A Discourse Analysis Towards Socially Responsible Human Resource Management. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 815–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, P.; Kim, T. Socially Responsible HR in Action: Learning from Corporations Listed on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index World 2018/2019. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrena-Martínez, J.; Fernandez, M.L.; Fernandez, P.M.R. Research proposal on the relationship between corporate social responsibility and strategic human resource management. Int. J. Manag. Enterp. Dev. 2011, 10, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahlawat, N.; Kundu, S.C. Exploring the connection between socially responsible HRM and citizenship behavior of employees in Indian context. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2021, 13, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swailes, S. Responsible talent management: Towards guiding principles. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2020, 7, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, N.; Gessner, B. Human resource performance metrics: Methods and processes that demonstrate you care. Cross Cult. Manag. Int. J. 2013, 20, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmotaleb, M.; Saha, S.K. Socially Responsible Human Resources Management, Perceived Organizational Morality, and Employee Well-being. Public Organ. Rev. 2020, 20, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qablan, N.; Farmanesh, P. Do organizational commitment and perceived discrimination matter? Effect of SR-HRM characteristics on employee’s turnover intentions. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 1105–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.d.G.M.C.; Coelho, A.F.M. The Antecedents of Corporate Reputation and Image and Their Impacts on Employee Commitment and Performance: The Moderating Role of CSR. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2019, 22, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, K.; Deng, X. How Different Components of Socially Responsible HRM Influences Affective Commitment. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2020, 2020, 12678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.; Morales-Sánchez, R.; Pasamar, S. Mapping the Link between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Human Resource Management (HRM): How Is This Relationship Measured? Sustainability 2020, 12, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.I.; Clark, L.A.; Clark, W.R.; Raffo, D.M. Re-examining systematic literature review in management research: Additional benefits and execution protocols. Eur. Manag. J. 2021, 39, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Criado, A.R. The art of writing literature review: What do we know and what do we need to know? Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Lim, W.M.; O’Cass, A.; Hao, A.W.; Bresciani, S. Scientific procedures and rationales for systematic literature reviews (SPAR-4-SLR). Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Chauhan, S.; Paul, J.; Jaiswal, M.P. Social entrepreneurship research: A review and future research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 113, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murschetz, P.C.; Omidi, A.; Oliver, J.J.; Kamali Saraji, M.; Javed, S. Dynamic capabilities in media management research. A literature review. J. Strategy Manag. 2020, 13, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M. Demystifying neuromarketing. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 91, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Health motive and the purchase of organic food: A meta-analytic review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Weissmann, M.A. Toward a theory of behavioral control. J. Strategic Mark. 2021, 29, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Benito, G.R.G. A review of research on outward foreign direct investment from emerging countries, including China: What do we know, how do we know and where should we be heading? Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2018, 24, 90–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrad, C.; Gherheș, V. A Human Resources Perspective on Responsible Corporate Behavior. Case Study: The Multinational Companies in Western Romania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrena-Martinez, J.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernandez, P. Drivers and Barriers in Socially Responsible Human Resource Management. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernández, P.M.; Aust, I. Socially Responsible Human Resource Management and Employee Perception: The Influence of Manager and Line Managers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombiak, E.; Marciniuk-Kluska, A. Socially Responsible Human Resource Management as a Concept of Fostering Sustainable Organization-Building: Experiences of Young Polish Companies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Zhou, E.; Gao, P.; Long, L.; Xiong, J. Double-Edged Effects of Socially Responsible Human Resource Management on Employee Task Performance and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Mediating by Role Ambiguity and Moderating by Prosocial Motivation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Zhou, E.; Gao, P. Influence of Perceived Socially Responsible Human Resource Management on Task Performance and Social Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Mestanza, J.; Cerezo Medina, A.; Cruz Morato, M.A. A Model for Measuring Fair Labour Justice in Hotels: Design for the Spanish Case. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revuelto-Taboada, L.; Canet-Giner, M.T.; Balbastre-Benavent, F. High-Commitment Work Practices and the Social Responsibility Issue: Interaction and Benefits. Sustainability 2021, 13, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, F.A.; Haque, A.; Rahman, S. Socially Responsible HRM, Employee Attitude, and Bank Reputation: The Rise of CSR in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koinig, I.; Weder, F. Employee Representatives and a Good Working Life: Achieving Social and Communicative Sustainability for HRM. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Kim, H. The Effect of Socially Responsible HRM on Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: A Proactive Motivation Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu-Gyamfi, M.; He, Z.; Nyame, G.; Boahen, S.; Frempong, M.F. Effects of Internal CSR Activities on Social Performance: The Employee Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-P.; Hu, H.-H.; Lin, C.-M. Consistency or Hypocrisy? The Impact of Internal Corporate Social Responsibility on Employee Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Cruz, P.; Noronha, E. Cornered by conning: Agents’ experiences of closure of a call centre in India. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 1019–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, C.; Davis, A.J. Ethics and social responsibility—Do HR professionals have the ‘courage to challenge’ or are they set to be permanent ‘bystanders’? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 2411–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Miao, Q.; Hofman, P.S.; Zhu, C.J. The impact of socially responsible human resource management on employees’ organizational citizenship behaviour: The mediating role of organizational identification. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mory, L.; Wirtz, B.W.; Göttel, V. Factors of internal corporate social responsibility and the effect on organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 1393–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrena-Martínez, J.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernández, P.M. Towards a configuration of socially responsible human resource management policies and practices: Findings from an academic consensus. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 30, 2544–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.; Sang, K. Socially ir responsible human resource management? Conceptualising HRM practice and philosophy in relation to in-work poverty in the UK. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 2185–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongo, C.I. Social Responsibility, Quality of Work Life and Motivation to Contribute in the Nigerian Society. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Zhang, H. Socially Responsible Human Resource Management and Employee Support for External CSR: Roles of Organizational CSR Climate and Perceived CSR Directed Toward Employees. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Jia, M. Multilevel Examination of How and When Socially Responsible Human Resource Management Improves the Well-Being of Employees. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 176, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, Q.; He, P.; Jiang, C. How and When Does Socially Responsible HRM Affect Employees’ Organizational Citizenship Behaviors Toward the Environment? J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 169, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrena-Martinez, J.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernández, P.M. The link between socially responsible human resource management and intellectual capital. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, R.; Manfredi, S.; Cuozzo, B.; Palmaccio, M. The profitable relationship among corporate social responsibility and human resource management: A new sustainable key factor. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2657–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorribes, J.; Celma, D.; Martínez-Garcia, E. Sustainable human resources management in crisis contexts: Interaction of socially responsible labour practices for the wellbeing of employees. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 936–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangi, F.; D’Angelo, E.; Daniele, L.M.; Varrone, N. Assessing the impact of socially responsible human resources management on company environmental performance and cost of debt. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1511–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Liao, S.; Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Guo, Z. The effect of socially responsible human resource management (SRHRM) on frontline employees’ knowledge sharing. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3646–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Socially responsible human resource practices and hospitality employee outcomes. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 757–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Mao, Y.; Morrison, A.M.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. On being warm and friendly: The effect of socially responsible human resource management on employee fears of the threats of COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 346–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, D.; Lämsä, A.-M.; Pučėtaitė, R. Effects of responsible human resource management practices on female employees’ turnover intentions. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2018, 27, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Carrion, R.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernandez, P.M. Evidence of different models of socially responsible HRM in Europe. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2019, 28, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin-Hi, N.; Rothenhöfer, L.; Blumberg, I. The relevance of socially responsible blue-collar human resource management. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2019, 41, 1256–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espasandín-Bustelo, F.; Ganaza-Vargas, J.; Diaz-Carrion, R. Employee happiness and corporate social responsibility: The role of organizational culture. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2021, 43, 609–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrena-Martínez, J.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernández, P.M. Socially responsible human resource policies and practices: Academic and professional validation. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2017, 23, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celma, D.; Martinez-Garcia, E.; Raya, J.M. Socially responsible HR practices and their effects on employees’ wellbeing: Empirical evidence from Catalonia, Spain. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2018, 24, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Samara, G.; Zollo, L.; Ciappei, C. Is internal CSR really less impactful in individualist and masculine Cultures? A multilevel approach. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. Bridging employee advocacy in anonymous social media and internal corporate social responsibility (CSR). Manag. Decis. 2021, 59, 2473–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvaiya, H.; Arrowsmith, J. Exploring the context and interface of corporate social responsibility and HRM. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bučiūnienė, I.; Kazlauskaitė, R. The linkage between HRM, CSR and performance outcomes. Balt. J. Manag. 2012, 7, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, M.P.; Bu, M. Examining the impetus for internal CSR Practices with digitalization strategy in the service industry during COVID-19 pandemic. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2021, 31, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Kang, H.; Dowling, P.J. Conditional altruism: Effects of HRM practices on the willingness of host-country nationals to help expatriates. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lythreatis, S.; Mostafa, A.M.S.; Pereira, V.; Wang, X.; Giudice, M. Del Servant leadership, CSR perceptions, moral meaningfulness and organizational identification- evidence from the Middle East. Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 30, 101772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-González, M.d.M.; Rubio-Andrés, M.; Sastre-Castillo, M.Á. Effects of socially responsible human resource management (SR-HRM) on innovation and reputation in entrepreneurial SMEs. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 321–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Stankevičiūtė, Ž.; Robina-Ramirez, R.; Díaz-Caro, C. Responsible Job Design Based on the Internal Social Responsibility of Local Governments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, Q. Socially responsible human resource management and hotel employee organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: A social cognitive perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goergen, M.; Chahine, S.; Wood, G.; Brewster, C. The relationship between public listing, context, multi-nationality and internal CSR. J. Corp. Financ. 2019, 57, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Benson, J. When CSR Is a Social Norm: How Socially Responsible Human Resource Management Affects Employee Work Behavior. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1723–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, U.; Goyal, P. A Bayesian network model on the interlinkage between Socially Responsible HRM, employee satisfaction, employee commitment and organizational performance. J. Manag. Anal. 2020, 7, 105–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, D.T. The effect of internal corporate social responsibility practices on pharmaceutical firm’s performance through employee intrapreneurial behaviour. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2020, 33, 1375–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechuga Sancho, M.P.; Martínez-Martínez, D.; Larran Jorge, M.; Herrera Madueño, J. Understanding the link between socially responsible human resource management and competitive performance in SMEs. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 1211–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giang, H.T.T.; Dung, L.T. The effect of internal corporate social responsibility practices on firm performance: The mediating role of employee intrapreneurial behaviour. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liu, L. Platform Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Innovation Performance: A Cross-Layer Study Mediated by Employee Intrapreneurship. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Fu, S.; Zheng, L. Corporate sexual equality and firm performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 1812–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.S. Socially Responsible Entrepreneurship as Innovative Human Resource Practice. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2018, 54, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterick, M.; Charlwood, A. HRM and the COVID-19 pandemic: How can we stop making a bad situation worse? Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2021, 31, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, M.; Spencer, D.A.; McLachlan, C.J.; Forde, C. COVID-19 and the uncertain future of HRM: Furlough, job retention and reform. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2021, 31, 904–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamzadeh, A.; Dana, L.P. The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: Challenges among Iranian startups. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2021, 33, 489–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veglianti, E.; Dal Zotto, C.; De Marco, M. Smart working in the COVID-19 emergency: A comparative study of the banking and insurance sectors. In Proceedings of the ITM Web of Conferences; Di Marzo-Serugendo, G., Drăgoicea, M., Ralyté, J., Eds.; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2021; Volume 38. [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg, J.; Alvesson, M. Meanings of Theory: Clarifying Theory through Typification. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 487–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, M. Ethics and HRM: A Review and Conceptual Analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 36, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, K. The Employee as ‘Dish of the Day’: The Ethics of the Consuming/Consumed Self in Human Resource Management. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Greenwood, M. Ethical Analyses of HRM: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, B. The one best way? ‘Scientific’ research on HRM and the threat to critical scholarship. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2015, 25, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dundon, T.; Rafferty, A. The (potential) demise of HRM? Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2018, 28, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirson, M. Humanistic Management: Protecting Dignity and Promoting Well-Being; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hegel, G.W.F. Grundlinien der Philosophie des Rechts; Pипoл Kлaccик: Moscow, Russia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E. The Division of Labour in Societya; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Honneth, A. Arbeit und Anerkennung Versuch einer Neubestimmung. Dtsch. Z. Philos. 2008, 56, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessler, G. Fundamentals of Human Resource Management, 5th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, C.; Harvey, G. Agonism and the Possibilities of Ethics for HRM. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braverman, H. Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Knights, D.; Willmott, H. Labour Process Theory; Macmillan: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, B.; Danford, A.; Howcroft, D.; Richardson, H.; Smith, A.; Taylor, P. ‘All they lack is a chain’: Lean and the new performance management in the British civil service. New Technol. Work Employ. 2011, 26, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huising, R. The Erosion of Expert Control Through Censure Episodes. Organ. Sci. 2014, 25, 1633–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaser, K. ‘If you are having a go at me, I am going to have a go at you’: The changing nature of social relationships of bank work under performance management. Work. Employ. Soc. 2016, 30, 1000–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellogg, K.C.; Valentine, M.A.; Christin, A. Algorithms at Work: The New Contested Terrain of Control. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2020, 14, 366–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, S.; Scully, M.A. It’s About Distributing Rather than Sharing: Using Labor Process Theory to Probe the “Sharing” Economy. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandini, A. Labour process theory and the gig economy. Hum. Relat. 2019, 72, 1039–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, A.; Tsoukas, H. The SAGE Handbook of Process Organization Studies; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, A. Process thinking in strategic organization. Strateg. Organ. 2007, 5, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.; Chia, R. Thinking becoming and emergence: Process philosophy and organization studies. In Philosophy and Organization Theory; Tsoukas, H., Chia, R., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2011; pp. 281–309. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, A.; Smallman, C.; Tsoukas, H.; Van de Ven, A.H. Process Studies of Change in Organization and Management: Unveiling Temporality, Activity, and Flow. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitlis, S.; Christianson, M. Sensemaking in Organizations: Taking Stock and Moving Forward. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2014, 8, 57–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgorodnichenko, N.; Edgar, F.; Akmal, A.; McAndrew, I. Sustainability through sensemaking: Human resource professionals’ engagement and enactment of corporate social responsibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarzabkowski, P. Strategy as Practice: Recursiveness, Adaptation, and Practices-in-Use. Organ. Stud. 2004, 25, 529–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, T.S.-C.; Law, K.K. Sustainable HRM: An extension of the paradox perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 100818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apascaritei, P.; Elvira, M.M. Dynamizing human resources: An integrative review of SHRM and dynamic capabilities research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2021, 100878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully-Russ, E.; Torraco, R. The Changing Nature and Organization of Work: An Integrative Review of the Literature. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2020, 19, 66–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; McDonald, P.; Mayes, R. Recruitment in the gig economy: Attraction and selection on digital platforms. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 4136–4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandini, A. Digital labour: An empty signifier? Media, Cult. Soc. 2021, 43, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Zotto, C.; Omidi, A. Platformization of Media Entrepreneurship: A Conceptual Development. Nord. J. Media Manag. 2020, 1, 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallas, S.P.; Schor, J.B. What Do Platforms Do? Understanding the Gig Economy. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2020, 46, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshandel Arbatani, T.; Norouzi, E.; Omidi, A.; Valero-Pastor, J.M. Competitive strategies of mobile applications in online taxi services. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2019, 16, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrahi, M.H.; Newlands, G.; Lee, M.K.; Wolf, C.T.; Kinder, E.; Sutherland, W. Algorithmic management in a work context. Big Data Soc. 2021, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del-Castillo-Feito, C.; Blanco-González, A.; Hernández-Perlines, F. The impacts of socially responsible human resources management on organizational legitimacy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 174, 121274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Zotto, C. Human Resource Leadership in Highly Dynamic Environments: Theoretically Based Analyses of 3 Publishing Companies. J. Media Bus. Stud. 2005, 2, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, J.; Oliver, J. Human Resource Management in the Media. In Handbook of Media Management and Economics; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Zotto, C.; Van Kranenburg, H. Management and Innovation in the Media Industry; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Omidi, A.; Dal Zotto, C.; Norouzi, E.; Valero-Pastor, J.M. Media Innovation Strategies for Sustaining Competitive Advantage: Evidence from Music Download Stores in Iran. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshandel Arbatani, T.; Asadi, H.; Omidi, A. Media Innovations in Digital Music Distribution: The Case of Beeptunes.com. In Competitiveness in Emerging Markets; Khajeheian, D., Friedrichsen, M., Modinger, W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 93–108. ISBN 9783319717227. [Google Scholar]

- Malmelin, N.; Virta, S. Managing for Serendipity: Exploring the Organizational Prerequisites for Emergent Creativity. Int. J. Media Manag. 2017, 19, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajeheian, D.; Friedrichsen, M. Innovation Inventory as a Source of Creativity for Interactive Television. In Digital Transformation in Journalism and News Media; Friedrichsen, M., Kamalipour, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 341–349. ISBN 978-3-319-27785-1. [Google Scholar]

- Siapera, E. Affective Labour and Media Work. In Making Media: Production, Practices, and Professions; Deuze, M., Prenger, M., Eds.; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 275–286. [Google Scholar]

- Eigler, J.; Azarpour, S. Reputation management for creative workers in the media industry. J. Media Bus. Stud. 2020, 17, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achtenhagen, L. Entrepreneurial orientation--An overlooked theoretical concept for studying media firms. Nord. J. Media Manag. 2020, 1, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, L.-P.; Salamzadeh, A. Why do Artisans and Arts Entrepreneurs use Social Media Platforms?: Evidence from an Emerging Economy. Nord. J. Media Manag. 2021, 2. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Khajeheian, D.; Tadayoni, R. User innovation in public service broadcasts: Creating public value by media entrepreneurship. Int. J. Technol. Transf. Commer. 2016, 14, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajeheian, D. Enterprise Social Media: Ethnographic Research on Communication in Entrepreneurial Teams. Int. J. E-Services Mob. Appl. 2018, 10, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFillippi, R. Dilemmas of Project-Based Media Work: Contexts and Choices. J. Media Bus. Stud. 2009, 6, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Peuter, G.; Young, C.J. Contested Formations of Digital Game Labor. Telev. New Media 2019, 20, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuze, M. Media Work; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rohn, U. Media Management Research in the Twenty-First Century. In Handbook of Media Management and Economics; Albarran, A.B., Mierzejewska, B., Jung, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 425–441. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, R.G. Unique Characteristics and Business Dynamics of Media Products. J. Media Bus. Stud. 2005, 2, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohn, U.; Evens, T. Media Management Matters: Challenges and Opportunities for Bridging Theory and Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Girija, S. Political Economy of Media Entrepreneurship: Power, Control and Ideology in a News Media Enterprise. Nord. J. Media Manag. 2020, 1, 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hesmondhalgh, D.; Baker, S. Creative Labour: Media Work in Three Cultural Industries; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Burrell, G.; Morgan, G. Sociological Paradigms and Organisational Analysis: Elements of the Sociology of Corporate Life; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).