Status and Trends in Forest Environment Transfer Tax and Information Interface between Prefectures and Municipalities: Multi-Level Governance of Forest Management in 47 Japanese Prefectures

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Contexts of Introduction of Forest Environment Transfer Tax

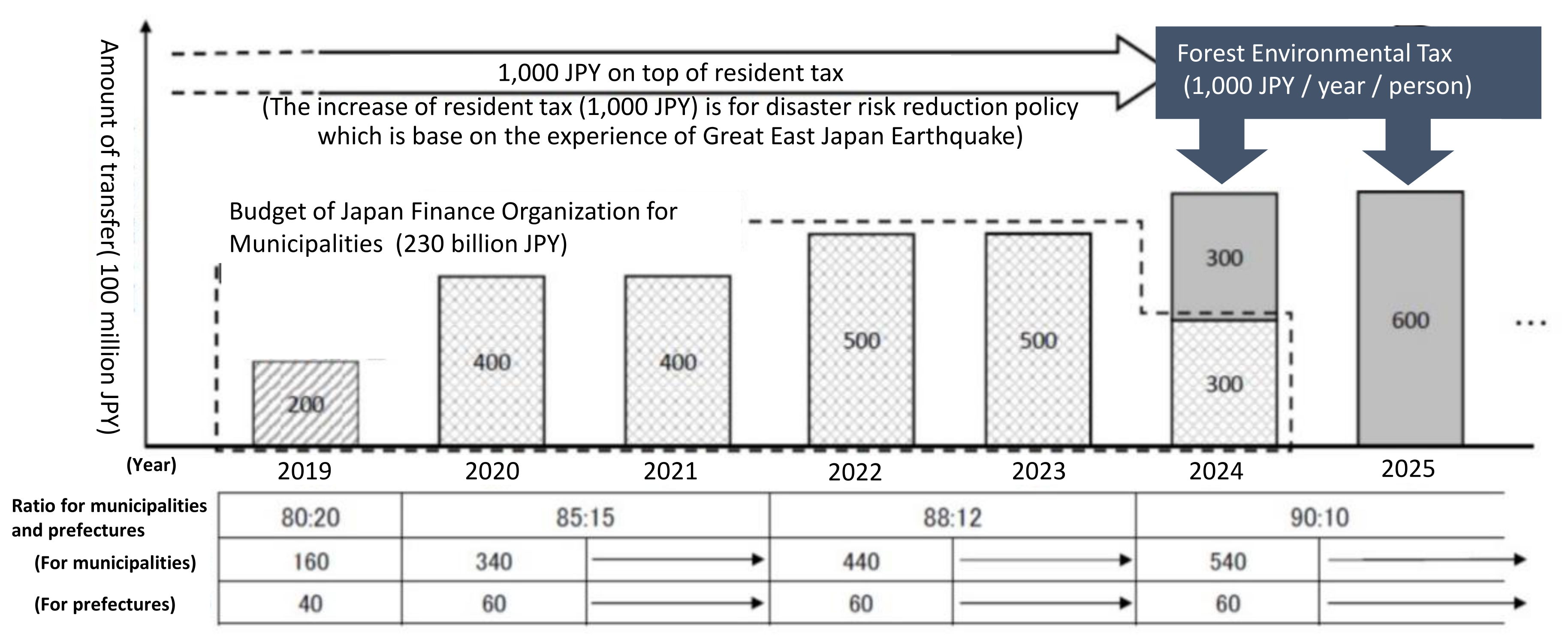

1.2. Overview of Forest Environment Transfer Tax and Challenges of Prefectures and Municipalities

1.3. Status of Prefectures and Their Roles to Support Municipalities

2. Review of Existing Studies and Concept of Multi-Level Governance

2.1. Review of Existing Studies on FETT and PreFET

2.2. Multi-Level Governance

3. Methods

4. Results and Discussion

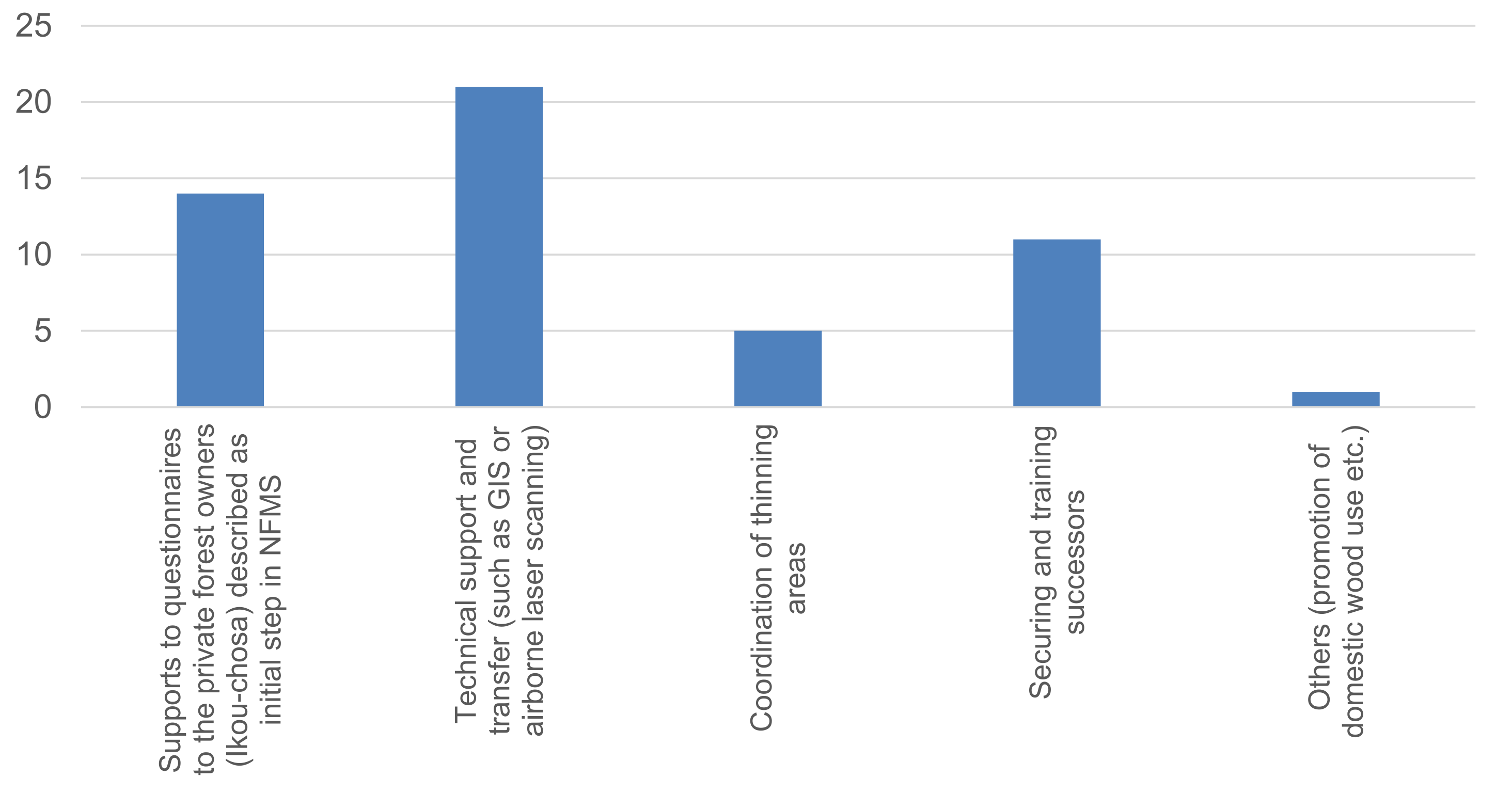

4.1. Budget and Supporting Activities under FETT

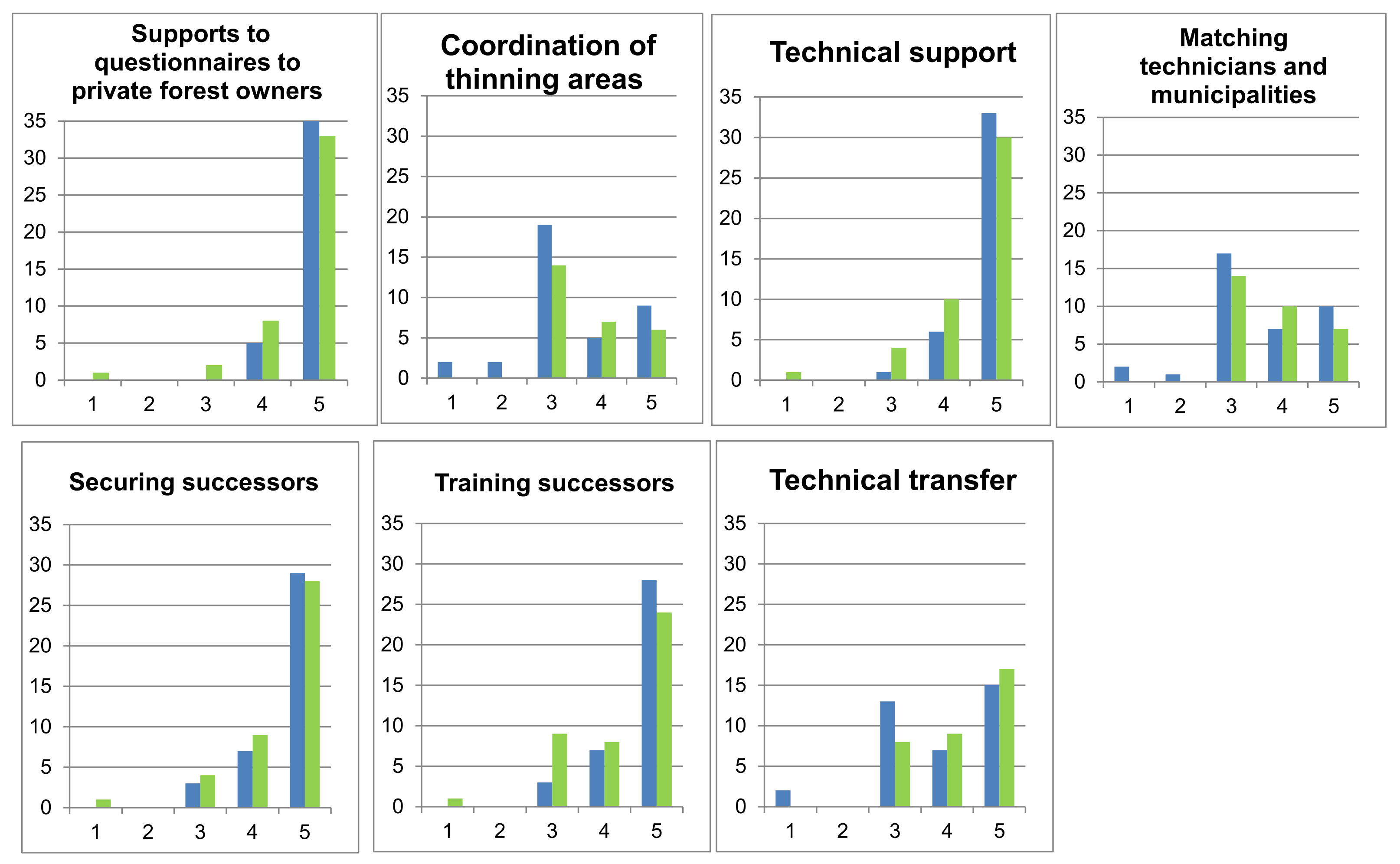

4.2. Priority of Supporting Activities for Municipalities under FETT

4.3. Streamlining FETT and PreFET in Prefectures

4.3.1. Relevant Forests

4.3.2. Differentiation of Supporting Activities: Promotion of Wood Use and Support for New Hires

4.3.3. Streamlining of Activities

4.3.4. Differentiation between PreFET and FETT in Terms of Scale

4.3.5. Disaster Prevention

5. Challenges and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matta, J.; Kerr, J. Can environmental services payments sustain collaborative forest management? J. Sustain. For. 2006, 23, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagnini, F.; Finney, C. Payments for environmental services in Latin America as a tool for restoration and rural development. Ambio 2011, 40, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D. Payments for forest-based environmental services: A close look. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 72, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, Y.; Kohsaka, R. Analysis of the distribution of forest management areas by the forest environmental tax in Ishikawa prefecture, Japan. Int. J. For. Res. 2016, 2016, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, S. The Mechanisms to Pay the Environment: The Book to Understand PES (Payment for Ecosystem Services); Daigaku Kyōiku Shuppan: Okayama, Japan, 2019. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kajima, S.; Uchiyama, Y.; Kohsaka, R. Private forest landowners’ awareness of forest boundaries: Case study in Japan. J. For. Res. 2020, 25, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carefully Check the Hidden Tax Increase. Nikkei Newspaper, 16 April 2018.

- New Forest Management System Started: Debate on Allocation of Revenue of Forest Environment Transfer Tax. Nikkei Newspaper, 14 November 2019.

- Kakizawa, H.; Japan Forestry Study Group. Deployment of the Forest Management Policy in Japan, and Its Facts and Limit; Japan Forestry Investigation Institution: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Tada, T. Breaking news about execution environment of forest environment transfer tax and attempt of analysis of local difference. Agric. For. Financ. 2020, 73, 33–53. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, H.; Kakizawa, H.; Hirata, K.; Tamura, N. The current state of and future trends in the forest administration of municipalities: Analysis of the postal questionnaire survey. J. For. Econ. 2020, 66, 51–60. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kohsaka, R.; Uchiyama, Y. Forest environmental taxes at multi-layer national and prefectural levels: Comparisons of 37 prefectures survey results in Japan. J. Jpn. For. Soc. 2019, 101, 246–252. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Forestry Agency 2020. Status of Forest Environment Transfer Tax, Document of Forest Administration Council (1st September 2020) Document 2-2. Available online: https://www.rinya.maff.go.jp/j/rinsei/singikai/attach/pdf/200109si-22.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Yoshihiro, K. Estimate and consideration of transfer standard of forest environment transfer tax. Jpn. Res. Inst. Local Gov. 2021, 484, 3–20. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Japan Forestry Investigation Institution, Management of using transfer tax and prefectural taxation: Aichi prefecture, liaison meeting of municipalities. 29 May 2019. (In Japanese)

- Uchiyama, Y.; Kohsaka, R. Utilization of forest environment transfer tax in ordinance-designated cities: Trend of urban forest policy and its diversity in Japan. J. Jpn. For. Soc. 2020, 102, 173–179. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaki, R. Beneficiary and burden of the forest environmental tax. Environ. Inform. Sci. 2019, 48, 43–48. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kohsaka, R.; Uchiyama, Y. Forest environment transfer tax, prefectural forest policy, and support for municipalities. J. Jpn. For. Soc. 2021, 103, 134–144. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohsaka, R.; Osawa, T.; Uchiyama, Y. Forest environment transfer tax and urban-rural collaboration: Case of Chichibu City and Toshima District in Japan. J. Jpn. For. Soc. 2020, 102, 127–132. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otani, M. Securing human resources dealing with new policies in prefectures, Utilization of seconded bureaucrat and private sector. J. Public Policy Stud. 2017, 17, 69–82. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Newig, J.; Fritsch, O. Environmental governance: Participatory, multi-level–and effective? Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, G. Structural policy and multilevel governance in the EC. In The State of the European Community; Cafruny, A., Rosenthal, G.T., Eds.; Lynne Rienner: Boulder, CO, USA, 1993; pp. 391–411. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrass, J.; Jordan, A. Multi-level governance and environmental policy. In Multi-Level Governance; Bache, I., Flinders, M., Eds.; Oxford Scholarship: Online, 2004; pp. 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, K. Multi-level environmental governance for sustainable development. Ann. Rep. Sociol. Soc. 2008, 37, 31–41. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Oyama, K. IPBES: The multilevel governance for conserving biodiversity. J. Rural Plann. Assoc. 2017, 36, 38–41. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Benson, K.J. A framework for policy analysis. In Interorganizational Co-Ordination: Theory, Research and Implementation; Rogers, D., Whitten, D., Eds.; Iowa State University Press: Ames, IA, USA, 1982; pp. 137–176. [Google Scholar]

- Dowding, K. Model or metaphor? A critical review of the policy network approach. Pol. Stud. 1995, 43, 136–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, M.M.; Coleman, W.D. Policy networks, policy communities and the problems of governance. Governance 1992, 5, 154–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, R.; Angelstam, P.; Myhrman, L.; Sädbom, S.; Ivarsson, M.; Elbakidze, M.; Andersson, K.; Cupa, P.; Diry, C.; Doyon, F.; et al. Evaluation of multi-level social learning for sustainable landscapes: Perspective of a development initiative in Bergslagen, Sweden. Ambio 2013, 42, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskitalo, E.C.H.; Baird, J.; Ambjörnsson, E.L.; Plummer, R. Social network analysis of multi-level linkages: A Swedish case study on northern forest-based sectors. Ambio 2014, 43, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keskitalo, E.C.H.; Pettersson, M. Implementing multi-level governance? The legal basis and implementation of the EU Water Framework Directive for forestry in Sweden. Environ. Policy Gov. 2012, 22, 90–103. [Google Scholar]

- Mukonza, R.M.; Mukonza, C. Implementation of green economy policies and initiatives in the City of Tshwane. J. Public Adm. 2015, 50, 90–107. [Google Scholar]

| Level | Established | Budget Size | Scope | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PreFET | Prefecture (37) | 2003 | 30 billion (total) | Diverse |

| FETT | Tax: National Implementation: municipality Support: prefecture | 2019 | 20 billion (2019) 40 billion (2020–2021) 50 billion (2022–2023) 60 billion (2024–) | Unmanaged privately owned artificial forests |

| Project Name/Type | Copenhagen Energy PES Scheme | Dōshi Water Source Forest Conservation Scheme (Yokohama City) | PreFET | FETT | Scheme of Slowing the Flow at Pickering |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country (Level of governmental bodies) | Denmark (municipal level) | Japan (municipal level) | Japan (prefectural level) | Japan (national level) | UK (national level) |

| Project objectives | Conservation of water sources and decreasing chemical use in forests | Conservation of water sources | Diverse (mainly for forest management) | Responding to the increase of unregistered owners and the Paris Accord | Risk management of flooding |

| Policy measures for forests | Payment for stopping chemical use and converting farmland to broad-leaved forest and purchase of farmland for tree planting | Thinning coniferous forests and increasing broad-leaved and mixed forests. Public-private partnership and volunteer activities | Thinning insufficiently managed forests, adding mixed forests, and environmental and forest education | Management of unmanaged artificial forests. Promotion of domestic woods. Education | Forest creation |

| Characteristic forest-related local roles | Conducting and managing tree planting by a local government | Consigned corporations conduct forest management | Prefectures and consigned corporations, such as forest associations, conduct the work | Both prefectures and municipalities could decide how to spend governmentally allocated funds. | Participation in land planning and management |

| Prefecture | Details of Revisions |

|---|---|

| Miyagi | Activities defined as being under the scope of the FETT will be excluded from the PreFET (Miyagi Environmental Tax) |

| Fukushima | The ordinance of the Fukushima Forest Environment Fund has been revised to make depositing the revenue of FETT in the fund possible. |

| Tochigi | Abolished two activities: 1. Promoting mixed forests with conifers and broad-leaved trees (Shinko–Konko–Rinka). Transition to natural forests by intensive thinning of artificial conifer forests. 2. Intensification of forest management by enlarging operational units (Segyo–Shyuyaku–Sokushin). Matching information (using databases known as “banks”) of owners and operators to enlarge operations in forests. |

| Ishikawa | Transfer management of artificial forests under PreFET to municipalities, because FETT is intended to fund the municipal management of such forests under NFMS. |

| Aichi | Activities under PreFET (Aichi Forest and Greening Tax) were reviewed in July 2018; the decision was made to continue such activities. To differentiate between PreFET and FETT, existing activities under PreFET that can be conducted under FETT, either by prefectures or municipalities, were abolished. For thinning of artificial forests, PreFET is necessary to cover target areas and will therefore remain unchanged in this regard. For Satoyama management, existing activities under PreFET that can be conducted under FETT, either by prefectures or municipalities, were abolished. However, support to NPOs and local residents will continue during the initial phase of FETT. This is because broad-leaved trees frequently observed in Satoyama forests grow rapidly and require continued management. Support for locals will also encourage self-organized activities. Support to municipalities for wood-use promotion, including those from thinning, are abolished; such activities can be conducted under FETT either by prefectures or municipalities. However, for the purpose of organizing national planting festivals in 2019, the prefecture will continue to support activities that improve public relations related to locally produced wood. The slogan of national planting festivals is “Wood use will bridge forests and cities.” |

| Mie | ○ FETT promotes the management of public forest land, training forest workers, and the promotion of prefectural woods ○ PreFET (Forest and Green Tax) promotes forests resilient to disasters, training of volunteers, and environmental education. They have provided a detailed comparative table of the two tax systems that explain; (1) Measures for unmanaged forests 1.1 Artificial forests 1.2 Satoyama bamboo 1.3 Eliminating trees that are a hazard to people (2) Securing and training new employees (3) Raising awareness (4) Promotion of wood use (5) Support |

| Shiga | The Ordinance on Prefectural Tax was revised (March 2019). As a prefectural tax would be based on the present idea (policies toward environmental consideration and cooperation among prefectural citizens), it was decided not to implement policies, such as support for municipalities, based on Forest Management Law. Instead, FETT would be used to support municipalities. The prefecture determined which roles were appropriate for itself and for its municipalities. Municipalities would be responsible for tasks such as the control of locally familiar unmanaged forests because FETT is mostly distributed for this purpose. The prefecture would develop mixed needleleaf and broadleaf forests in isolated locations. This would benefit larger areas. |

| Kyoto | With the introduction of FETT, the prefecture reviewed municipal grants from excess taxes to avoid overlapping accounts. Policies, such as measures to eliminate dangerous trees, were expanded to strengthen disaster-prevention measures in preparation for increasing frequency of natural disasters. |

| Osaka | To differentiate PreFET and FETT, PreFET will be mainly used for urgent disaster risk reduction measures and FETT will not be used for such issues. Measures of the promotion of wood products for building childcare-support facilities and training the successors of forestry will not be implemented by PreFET after 2019, because FETT will be used to implement those measures. |

| Nara | Given the strong need to control unmanaged forests, the prefecture is concerned that some municipalities may have insufficient funds if they only rely on FETT. Prefectures will, therefore, continue to control unmanaged forests. Municipalities will take on measures for enhancing forests’ resilience to disasters based on the current assessment of damage from increasing natural disasters. This differs explicitly from the prefecture’s control of unmanaged forests. Considering the broad usage of FETT at the municipality level, the prefecture limits its measures to wider forests with the aim of benefiting trans-municipal areas. (Changing measures after 2021 is currently being considered.) |

| Wakayama | The use of PreFET was revised with regard to activities that can be covered under FETT, such as thinning of mixed forests. PreFET will be used for the thinning of artificial forests and high disaster-risk land management near villages, for which FETT cannot be used. |

| Okayama | PreFET will be used for measures related to wider areas, comprising several municipalities, while FETT will be mainly used to support municipal forest management. This differentiates between PreFET and FETT. Thinning: Measures under PreFET are conducted based on the survey results of forest owners. Results are especially important in areas surveyed based on Forest Management Law. Measures for forest insect pests: PreFET will be used to implement urgent measures in wider areas composed of several municipalities. Human resource development: PreFET will be used for measures on wider multi-municipal areas, while FETT will be used for municipal measures. Facilitating the use of timber and wood products: PreFET will not be used for public buildings constructed using FETT. Information sharing: PreFET will be used for measures on wider, multi-municipal areas, while FETT will be used for municipal measures. |

| Ehime | FETT is used only for entrusting forest management to municipalities and the management of unprofitable forests. PreFET is used for the management of profitable forests, human resource development, and facilitating the use of timber and wood products. A measure based on PreFET to support municipal proposals was suspended, considering that FETT can be used for this purpose. |

| Kochi | The guideline of PreFET has been revised to show that PreFET cannot be used for the measures implemented by the FETT framework. |

| Fukuoka | An external PreFET evaluation committee recommended the differentiation measures under the jurisdiction of PreFET versus FETT. Support of wood product exhibitions in public buildings has, therefore. Been removed from the list of PreFET-relevant measures. |

| Oita | Human resource development and capacity building in the forestry sector are implemented using FETT. |

| Miyazaki | Although previously conducted using PreFET, thinning, registration of public forests, and promotion of prefectural wood products are now conducted using FETT. Considering the goal of PreFET (conservation of forests), we have strengthened the use of PreFET funds for conservation-related measures, such as driftwood outflow prevention and reforestation. |

| Kagoshima | Prefectural ordinance of PreFET has been revised to change the name of PreFET from “Forest Environmental Tax” to “Prefectural Tax for Our Forest managements” to differentiate FETT and PreFET. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kohsaka, R.; Uchiyama, Y. Status and Trends in Forest Environment Transfer Tax and Information Interface between Prefectures and Municipalities: Multi-Level Governance of Forest Management in 47 Japanese Prefectures. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1791. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031791

Kohsaka R, Uchiyama Y. Status and Trends in Forest Environment Transfer Tax and Information Interface between Prefectures and Municipalities: Multi-Level Governance of Forest Management in 47 Japanese Prefectures. Sustainability. 2022; 14(3):1791. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031791

Chicago/Turabian StyleKohsaka, Ryo, and Yuta Uchiyama. 2022. "Status and Trends in Forest Environment Transfer Tax and Information Interface between Prefectures and Municipalities: Multi-Level Governance of Forest Management in 47 Japanese Prefectures" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1791. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031791

APA StyleKohsaka, R., & Uchiyama, Y. (2022). Status and Trends in Forest Environment Transfer Tax and Information Interface between Prefectures and Municipalities: Multi-Level Governance of Forest Management in 47 Japanese Prefectures. Sustainability, 14(3), 1791. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031791