Abstract

This study examines how the social climate was associated with the psychological response during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Using a structural equation model linking the economic crisis to the social climate (pandemic fear, social and psychological distress, civil protection, and population’s response) and to the psychological response (perspectives of life and reconsidering values), we tested their multivariate relationships in a Greek academic community sample. At the first level of the model, the economic crisis was significantly associated with the social climate: pandemic fear, social/psychological distress, and civil protection. At the second level, social/psychological distress was associated with the pandemic fear and civil protection, whereas the pandemic fear was associated with the population’s response to governmental measures. At the third level, civil protection was directly associated with the psychological response resilience variables: perspectives of life and reconsidering values. The model explained a significant amount of the variance in the population’s response (62%), reconsidering values (42%), and perspectives of life (32%). Moreover, women presented higher levels of social/psychological distress, pandemic fear, and perspectives of life. Finally, younger people were more affected by the social/psychological distress and pandemic fear, whereas older people presented higher levels in the population’s response to governmental measures.

1. Introduction

The novel health crisis regarding the COVID-19 pandemic created an emergency for all countries, causing an enormous impact on every aspect of social and economic life. The long-lasting strict measures throughout 2020–2021 that were imposed on the population of most countries to mitigate the virus transmission including lockdown, confinement, quarantine, and social distancing brought unprecedented changes in individuals’ lives and livelihoods leading to social and psychological distress [1].

1.1. Social Climate

There is a growing body of research into the social response to the virus and social climate in general. For example, Everett et al. [2] reported that communicating advice using a deontological appeal to invoke a sense of civic duty had some effect on peoples’ behavior that enhanced a delay in the transmission of the virus. Other researchers reported that inducing empathy for vulnerable members within a community encouraged the reduction of physical and social interactions [3], while appealing to altruistic motivations to comply with social distancing instructions also proved to be effective to persuade the population to follow these practices [4].

The present study aimed to explore the impact of the official narrative communicated mainly through the traditional media against the spread of the virus on the social climate and the formulation of peoples’ response, their values, as well as their perspectives of life, given the novel stressful situation. We conducted the research among the academic community of a university in northern Greece in May 2020 in the first wave of the pandemic. Thus, our study reflects the responses to this period and does not extend to the later waves of the pandemic.

Many European countries (Spain, Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, United Kingdom, France, Switzerland, etc.) were severely hit by the pandemic during the first wave. Greece was not among the European countries mostly hit at the time due to several factors. The GSCP in Greece implemented a strict, horizontal lockdown policy escalating between 10 March and 23 March (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker [OxCGRT] n.d.). These early interventions effectively limited the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus leading to low cumulative mortality during the first pandemic wave [5,6]. Piovani et al. [5] evaluated the efficacy of the early application of nonmedical interventions on COVID-19 mortality in the first pandemic wave among 37 countries. In countries such as Greece with low cumulative mortality during the first wave, the early application of mass gatherings, bans, and school closures was associated with an essential reduction in COVID-19 mortality. Greece’s handling of COVID-19 was presented in this period as a “success story” in media and early scientific literature [7].

At the time of the first wave, the official government narrative focused on “buying time” to develop public health resources effectively to manage future waves of the pandemic. Although the country focused on hospital preparedness, strategic mistakes in epidemiological surveillance and health communication in the fight against COVID-19 resulted in implementing a second long and strict horizontal lockdown. Greece had one of the highest COVID-19 death rates in Europe during the second wave [8,9]. Thus, the “success story” of the first wave was relatively short lived. A reverse situation followed it during the subsequent waves characterized by an increasing cumulative mortality pattern that has currently brought the country to mid-levels in Europe as of November 2021. [10]. It seemed that the time that the Greek government “bought” during the first lockdown to reorganize public health services to develop ways to detect, isolate, and care for incidents, as well as prepare and educate the population was not made most productive [8].

1.2. Psychological Response

The COVID-19 crisis has had an impact on the way people perceive their world and everyday lives. The nature of the virus, with high transmissibility and infectivity and a relatively high mortality rate for older ages, has been associated with the psychological distress of the general population. People have had to deal with the risk of infection, fear of death, financial uncertainty, reduction of social contact at work and schools as well as deprivation of socializing in outdoor leisure activities. Furthermore, they sometimes had to confront the loss of family members, close or distant relatives, friends, colleagues, or acquaintances who were hit by the virus and lost their lives and to respond to a number of stressful factors that were caused by this new crisis [1]. Resilience, as a psychological response, has been defined “as a class of phenomena characterized by patterns of positive response in the context of significant adversity or risk” [11] as well as an adaptive ability to respond to some real, experienced adversity [12]. It is important to point out that the COVID-19 crisis was preceded by ten years of economic crisis (2010–2020) that has had an enormous impact on people’s economic and social life. The damage and suffering that austerity brought to Greece was severe and led the country to the edge of social collapse by rising unemployment and falling consumption, while at the same time leading one third of the Greek population below the poverty line [13]. Research carried out during April 2020 presented evidence from a mental helpline in Greece and revealed that about 30.4% of the calls were germane to anxiety over the economy. Moreover, it suggested that calls at that time addressed the restrictive measures more than COVID-19 per se, “while fears for the economy were reminiscent of the prior financial crisis” [14] (p. 408).

Several studies dealing with the psychological side effects of the antipandemic measures taken to contain the spread of COVID-19 have seen the light of publication. Some of these studies focus on the traumatic stress reactions and psychological impact (tension, anxiety, fear, stress, depression, and despair) and coping strategies of a psychological crisis of the general population, front-line medical staff, and patients in the USA, China, and Spain [15,16,17]. Others focus on particular population categories, such as university communities and higher education students in Spain and Greece, respectively [18,19,20], suggesting that students are at an increased risk to develop depression and suicidality in relation to the pandemic outbreak. Some studies deal with the impact of the long-run effects of the COVID-19 economic recession on mortality and life expectancy among unemployed people and, particularly, one study suggests that COVID-19-related unemployment is two to five times higher than the typical unemployment, resulting in an increase in mortality and drop in life expectancy [21]. In addition, although less assessed, studies have shown an increased rate of suicidal ideation in the first month of the pandemic [22,23,24]. In general, studies suggest that there has been a substantial and, in some cases, an alarming increase in the psychological impact of the COVID-19 crisis.

Planchuelo-Gόmez et al. [15] evaluated the psychological impact of the COVID-19 crisis and lockdown among the general population in Spain. Constant news consumption about COVID-19 was found to be positively associated with symptomatic scores and daily physical activity to be negatively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. Quite to the contrary, Daly and Robinson [16] in the USA found that at the emergence of the COVID-19 crisis there was an increase in distress among the general population, which diminished with time, while the population seemed to develop a level of resilience in mental health as a response to the pandemic. Meanwhile, the online survey of Odrozola-Gonzalez et al. [18] among students in the university community of Valladolid in Spain revealed that the COVID-19 confinement impacted the students of this academic community. Scores relating to anxiety, depression, and stress were estimated from moderate to extremely severe, mostly among arts and humanities and social sciences students and less among engineering and architecture students. Along the same lines, a study among university students in Greece investigated the rate of clinical depression of this population during the lockdown in spring 2020. The study revealed that the students (especially female ones) were at high risk of developing depression and suicidality in relation to the COVID-19 outbreak [19]. In our study, we were interested in looking at how the perception of the economic crisis and the social climate factors were associated with each other and with people’s psychological response during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.3. Civil Protection Narrative and Social Climate

During the first wave of the pandemic, the civil protection narrative was communicated almost exclusively through the traditional media. The program of the majority of the TV channels included regular daily briefs of the Civil Protection with the presence of ministers and medical experts, as well as regular public addresses of the Prime Minister in an attempt to reach the civilians at every corner of the country [25]. The communication strategy organized by the Civil Protection was live, mainly television broadcasts, which interrupted the regular daily programs, based on a specific script. In brief, the narrative of the Civil Protection about the COVID-19 pandemic during the first wave was built up by using media events as a vehicle of communicating to the public the measures taken to restrict the spread of the pandemic and, furthermore, to justify and legitimize action and cultivate a social climate that would be supportive and consensual of the governmental choices. Results from research conducted during the same period [14] revealed that the communication overload regarding the risks associated with COVID-19 led people to develop negative thinking and negative emotions. Thus, we hypothesized that the response of the people to the COVID-19 crisis during the first wave of the pandemic might reflect the official narrative of the Civil Protection of the Ministry of Citizen Protection.

1.4. Scope and Hypotheses

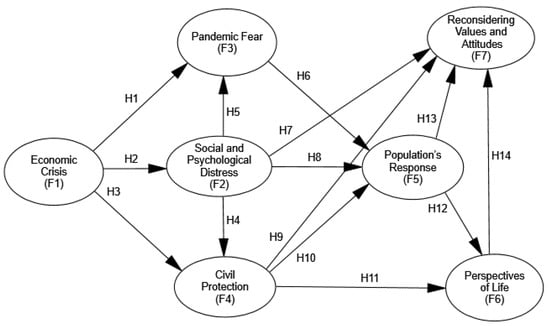

The present study focuses on the COVID-19′s social climate and variables of individuals’ psychological responses during the first wave (spring 2020) in Greece. We present and test a theoretical model (see Figure 1) of how the perception of the economic crisis and social climate factors are directly and indirectly associated with each other and with peoples’ psychological responses. We should note that the existing psychological scales did not apply to the novel situation of the COVID-19 pandemic. Most of them have a clinical orientation, and the most general scales were not appropriate for the scope of the present study, which focuses on the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, we should underline that in the novel situation of the first wave of the pandemic, there was much space for considering new conceptualizations and insightful approaches. However, the items of the two emerging factors (F6 Perspectives of life and F7 Reconsidering values) were inspired by the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale [26] adapted to the COVID-19 situation.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model for the association of the COVID-19 social climate with psychological variables.

The a priori model required by using structural equation modeling (SEM) constitutes a four-level approach to the relationships among sets of variables: (a) perception of economic crisis, (b) COVID-19′s social climate (social and psychological distress, pandemic fear, civil protection by the General Secretariat for Civil Protection (GSCP), and population’s response to those interventions, and (c) psychological responses (perspectives of life and values) (see Figure 1). We hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1. (H1).

A meaningful proportion of psychological responses can be significantly explained by a model of perceived economic crisis and the COVID-19 social climate.

Hypothesis 2. (H2).

The variation in the population’s responses can be explained by the three variables of the COVID-19 social climate (social and psychological distress, pandemic fear, and civil protection).

Hypothesis 3. (H3).

The variation in perceived economic crisis was influenced the three variables of COVID-19 social climate (social and psychological distress, pandemic fear, and civil protection) at the mesolevel.

In addition, we explored whether women were more affected in terms of the pandemic fear, social and psychological distress, reconsidering values, and perspectives of life.

RQ1: Did women exhibit different levels of psychological response (i.e., pandemic fear, social and psychological distress, reconsidering values, and perspectives of life) compared to men?

RQ2: Did younger respondents aged 25 and below exhibit different levels of perceived social climate (civil protection and response to governmental measures) compared to older respondents aged 26 years and above?

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Sampling Process

An anonymous, online survey was conducted among an academic community (students, academic staff, and administrative staff) of the School of Social Sciences and Humanities at a Greek university in May 2020. We collected our data through a questionnaire, using Google Forms. Our sample included 522 participants who provided full data (participation rate about 40%). Among the respondents, 32% were male, and 68% were female. The School’s student population consisted of 82.56% female and 17.44% male students. In addition, 75.9% participants were under 25 years old, 8.0% between 26–35, 8.2% between 36–45, 6.1% between 46–55, and 1.7% were over 56 years old. The data were collected from May to July 2020. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Western Macedonia.

2.2. Measures

Our data were collected through a questionnaire designed on a Likert five-point scale. The questionnaire consisted of two parts. Part A included questions about the participants’ demographics. Part B initially included 40 questions designed to investigate perceptions of economic crisis, COVID-19 social climate, and psychological variables. The factor analysis yielded seven factors, including 22 items out of the initial total of 40 items. These factors were the following: F1 Economic crisis, F2 Social and psychological distress, F3 Pandemic fear, F4 Civil protection, F5 Population’s response, F6 Perspectives of life, and F7 Reconsidering values, (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Definition of variables.

2.3. Endogenous Variables

All endogenous variables were measured by asking respondents how much they agreed with items on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). The statements of those items are described in Table 1. The Social and psychological distress scale contained four items and presented satisfactory internal consistency (α = 0.768). A confirmatory factor analysis indicated an acceptable fit (N = 522, χ2 = 0.004, p = 0.948). Pandemic fear contained one item measured on a scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree) with M = 3.84 and SD = 1.05. The Civil protection scale presented acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.646), and a confirmatory factor analysis indicated an acceptable fit (N = 522, χ2 = 1.022, p = 0.312). The Population’s response scale presented good internal consistency (α = 0.813), and a confirmatory factor analysis indicated an acceptable fit (N = 522, χ2 = 0.879, p = 0.349). The Perspectives of life scale presented a satisfactory internal consistency (α = 0.723), and a confirmatory factor analysis indicated an acceptable fit (N = 522, χ2 = 10.497, p = 0.001). Finally, the Reconsidering values scale presented good internal consistency (α = 0.830), and a confirmatory factor analysis also pointed to an acceptable (N = 522, χ2 = 0.014, p = 0.907).

2.4. Exogenous Variables

The exogenous variable of Economic crisis was measured by asking respondents how much they agreed with four statements on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree), as described in Table 1. The scale presented acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.559), and a confirmatory factor analysis indicated an acceptable fit (N = 522, χ2 = 3.094, p = 0.079, df = 1, RMSEA = 0.000, [90%CI = [0.000–0.149], GFI =.996, AGFI= 0.976, CFI = 0.986).

3. Findings

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 and IBM SPSS Amos 24 version software. As mentioned above, the measurement model was assessed using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). The reliability, convergent, and discriminant validity of the constructs were also assessed. Convergent validity was satisfactory by using two standards: The composite reliability (CR) of the constructs ranged from 0.753 to 0.873, above the recommended threshold of 0.6 [27]. The standardized indicator factor loadings for the observed indicators, shown in Table 2, were all statistically significant and exceeded 0.5, greater than the recommended 0.4 value [28]. Therefore, the conditions for convergent validity were met. Discriminant validity was evaluated by comparing the possible relationships between constructs with the square roots of AVE values [29]. The average variance extracted (AVE) of each construct ranged from 0.508 to 0.633 and exceeded the 0.5 value [29]. Thus, discriminant validity was sustained [30]. Moreover, the modification indices recommended no meaningful adjustments to the model.

Table 2.

Standardized factor loadings and individual item reliability.

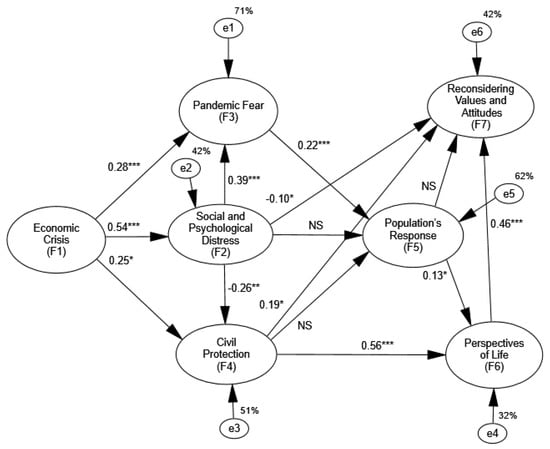

Once the constructs met the required measurement standards, the relationships between the constructs were estimated. Then, to investigate the hypothesized model (Figure 1), we applied a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) using maximum likelihood estimation.

The model’s overall goodness-of-fit was assessed using a combination of measures; these measures and recommended values are presented in Table 3 (columns 1 and 2). Thus, an adequately fitted model should have a chi-square/df ratio of less than 5 [31]; the adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), comparative fit index (CFI), normed fit index (NFI), incremental fit index (IFI), and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) values should be greater than 0.90 [30]; a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) should be less than 0.05 [32]. Therefore, the structural model illustrated in Figure 2 was satisfactory (see Table 3) because all model indicators were satisfactory according to the recommended values in the literature.

Table 3.

Evaluation of model goodness-of-fit.

Figure 2.

Results of the structural equation modelling show statistically significant paths. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, and NS: Not significant.

We further investigated the strength and direction of the relationships between the theoretical constructs of the structural model. The full model results are presented in Table 2 and Table 4.

Table 4.

Structural equation model results, standardized coefficients.

H1 suggested that a meaningful proportion of an individual’s psychological responses could be significantly explained by a model of perceived economic crisis and COVID-19 social climate. Indeed, 32% of the Perspectives of life variance and 42% of the Reconsidering values variance were explained by our structural model focusing on the COVID-19 social climate. The path from Perspectives of life to Reconsidering values was significant (β = 0.46, SE = 0.11, p < 0.001), and Civil protection was positively associated with Perspectives of life (β = 0.56, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001). Finally, Civil protection was directly and positively associated with the Reconsidering values factor (β = 0.19, SE = 0.09, p < 0.05), whereas Social and psychological distress was marginally and negatively associated with the Reconsidering values factor (β = −0.10, SE = 0.05, p < 0.05).

H2 suggested that variation in population responses could be explained by the three variables of the COVID-19 social climate (Social and psychological distress, Pandemic fear, and Civil protection). Indeed, 32% of the Population’s response variance was explained by the model. However, only the Pandemic fear was positively associated with the Population’s response factor (β = 0.22, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001).

H3 suggested that the perceived Economic crisis could influence the three variables of the COVID-19 social climate (Pandemic fear, Social and psychological distress, and Civil protection) at the mesolevel. Indeed, 71% of the Pandemic fear variance, 42% of the Social and psychological distress variance, and 51% of Civil protection were explained by the model. Specifically, the perceived Economic crisis was moderately associated with the Pandemic fear variable (β = 0.28, SE = 0.14, p < 0.001, positively associated with Social and psychological distress (β = 0.54, SE = 0.13, p < 0.001), and weakly and positively associated with Civil protection (β = 0.25, SE = 0.15, p < 0.05). In addition, Social and psychological distress was positively associated with the Pandemic fear (β = 0.39, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001) and negatively associated with the Civil protection measures (β = −0.26, SE = 0.08, p < 0.01).

Regarding our research question RQ1, we tested whether the factors F2, F3, F6 and F7 differed in terms of sex using the independent samples t-test [33]. Table 5 shows the means and standard deviations of the variables for both groups. Women (N2 = 355) reported higher levels than men (N1 = 162) on Economic crisis (t(520) = −2.12, p = 0.035), Social and psychological crisis (t(276.3) = −2.33, p = 0.020), Pandemic Fear (t(296.2) = −2.03, p = 0.043), and Perspectives of life (t(267.5) = −3.88, p = 0.000). There was no significant effect for sex regarding Civil protection (t(271.5) = −0.34, p = 0.732), Population’s response (t(520) = −1.04, p = 0.299), and Reconsidering values (t(520) = −1.33, p = 0.174).

Table 5.

Means and standard deviations of the factors by sex and age group.

Regarding our research question RQ2, we tested whether the factors F2, F3, F6 and F7 differed in terms of age group using the independent samples t-test. Table 5 shows the means and standard deviations of the variables for both groups. Younger respondents (N2 = 396) reported higher levels than older respondents (N1 = 126) on Social and psychological crisis (t(520) = 2.55, p = 0.011) and Pandemic fear (t(185.3) = 2.64, p = 0.009). Instead, older respondents reported higher levels than younger respondents on Population’s response to governmental measures (t(250.9) = −2.182, p = 0.030). There was no significant effect for the age group regarding the other variables: Economic crisis (t(520) = 0.571, p = 0.568), Civil protection (t(234.6) = −0.624, p = 0.533), Perspectives of life (t(242.4) = −0.653, p = 0.514), and Reconsidering values (t(520) = 0.33, p = 0.974).

4. Discussion

Overall, in the present study with an academic community sample, the response of people to the COVID-19 crisis during the first wave of the pandemic seemed to reflect to a great extent the official narrative of the Civil Protection of the Ministry of Citizen Protection. It is clearly presented in our results that the official narrative accomplished its purpose and created a social climate in favor of the governmental policies at that time.

A significant amount of the variance in population response was explained by our structural model. More specifically, the Pandemic fear (stated as “fear for our lives”) was positively associated with the population response factor. Overall, the structural model, including COVID-19 social climate factors, accounted for 32% of the Perspectives of life variance and 42% of the Reconsidering values variance. These outcome factors in our model can typically be considered psychological responses, including a psychological resilience component.

Individuals seemed to develop a level of psychological resilience, defined as positive subjective responses (e.g., Perspectives of life and Reconsidering values) in the context of an adverse fact, such as the Pandemic fear related to a sense of uncertainty, agony, stress, and fear [11,12]. Rutter [34] suggested that psychological resilience is a process and not a personality trait; thus, it is not enough to identify only personal protective factors. In this perspective, psychological resilience is characterized as a dynamic and interactive process, that is, individual traits and personal reserves act protectively and interact with specific external factors to promote the individual’s psychological resilience [34]. This dynamic and interactive notion of resilience seems to be consistent with our findings of the interaction between the social climate and positive subjective psychological responses during the first wave of the pandemic crisis.

It is also noted that Civil protection was strongly associated with the Perspectives of life and weakly associated with the Reconsidering values factors. People in Greece strongly believed that the COVID-19 outbreak was effectively controlled by the Greek government, which had taken the correct measures (e.g., social distancing, strict lockdown, stay-at-home measures, and restriction of movement). This belief made people, especially the older participants (aged 26 years and above), react respectively during the first phase of the pandemic. Thus, in our study, people tended to state that the pandemic had some positive impact on their life perspectives and values (e.g., “appreciate nature more,” “redefine the relationship with the natural environment,” “pandemic was an opportunity for self-reflection,” “an opportunity to review goals and priorities,” “spend more time with family at home,” and “develop new skills in terms of mental resilience”). Despite the several restrictions to personal, social, and political life in Greece, the vast majority of people accepted the situation and tried to rationalize their emotions within this novel situation [35].

Several ethnological and evolutionary approaches on emotions have revealed that emotions function to organize human behavior in ways appropriate to respond to environmental and social demands [36,37]. Culture is seen as having a strong influence on individuals coping and reacting to emotions, such as fear, anger, sadness, etc., as well as on cognitive and behavioral attempts to deal with such emotions and their causes [37]. Fear is defined as “the usually unpleasant feeling that arises as a normal response to realistic danger” [38] (p. 5). We found in this study that the Pandemic fear (“fear for our life because of the SARS-CoV-2”) was positively associated with the Population’s response factor. The pandemic fear can be viewed as a collective emotional experience where cultural formulations of emotion are reconceptualized and give new emphasis on the social dimension of this experience. Following this approach, our study revealed that people were led to the prioritization of values and new perspectives of life corresponding to a crisis [35]. In many cases, people tended to find the positive aspects of the situation, romanticizing the positive response to the crisis. This is not surprising. Karl Polanyi (1944/2001) [39] observed that at times “when both the economic and the political systems were threatened by complete paralysis … [f]ear would grip the people, and leadership would be thrust upon those who offered an easy way out at whatever ultimate price.” (p. 244). In times of turmoil when danger threatens the social systems with collapse, and life itself is at risk, many people, to face this fear, spontaneously respond by obeying any leadership that offers them an easy emotional way out regardless of the price [39]. Spinoza [40] (chapter 3, par. 3) also observed that in critical times, the political life is dominated by fear and hope. Hope refers to positive feelings, such as Perspectives of life and Reconsidering values in our model, and seems to counterbalance strong negative feelings, such as the Pandemic fear. Mass media might have played an essential role in generating mass fear during the first pandemic wave, presenting pictures of death and lament (i.e., Bergamo’s pictures showing hundreds of coffins piled up in trucks from the neighboring Italy) It has been suggested that information overload generated negative thinking and anger towards the pandemic among people during the first wave, and this consequently made them less persuaded by the risk messages. [9].

Our study further revealed that women were more affected by the first wave of the COVID-19 crisis in terms of social and psychological distress, pandemic fear, and perspectives of life. We have already referred to studies that reported similar findings. For example, a study among university students in Greece investigated the rate of clinical depression of this population during the lockdown in spring 2020 and revealed that the female participants were at a higher risk than male ones to develop depression and suicidality in relation to the COVID-19 outbreak [19].

Furthermore, our present study has also revealed that younger respondents, aged 25 and below, were more affected by the social and psychological distress and presented higher levels of pandemic fear, whereas older respondents aged 26 years and above were more sensitized to the Population’s response to governmental measures and presented lower levels of Pandemic fear. The finding that older respondents reported higher levels than younger respondents to the Population’s response to governmental measures, whereas had lower levels of Pandemic fear, may relate to greater responsiveness to mass media. This is consistent with the findings of other studies in Italy [41], China [42], and France [43,44] suggesting that psychological disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic were more frequent among young adults due to the sudden rupture of their lifestyle since they usually spend more time outside the home and have more of a social life than older people. Besides, for those among them who are students, the impact of the lockdown on their academic life might create insecurity about their future professional life [43,45,46].

5. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

The Civil Protection official narrative was mediated by the mass media. The inclusion of a mass media variable might have made the model stronger, having more explanatory power. Future research could explore how mass and social media affect the population’s response and individual psychological responses, such as psychological resilience in the ongoing pandemic crisis. In addition, the Pandemic fear factor in our model included only one variable. Multifaceted items of this factor, such as fear for the lives of family members (e.g., elderly) and not only fear for one’s own life and fear for work disturbances (i.e., loss and working conditions change), might have revealed a more important role of this factor in a model connecting the social climate to psychological responses. The present study tried to capture, among other things, the psychological impact of the pandemic during the first wave (spring 2020) by testing new psychological scales. Future research could revalidate the scales used in this study in a new sample and for the subsequent waves of the pandemic or test existing psychological measures (e.g., psychological distress and fear) to answer the research question of the present study regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. Another limitation of the present study stems from the sample that is representative of the study’s population, which is mainly comprised of undergraduate students of the School of Social Sciences and Humanities at a Greek university. Thus, the dominance of female students in our sample can be explained by the fact that 82.56% of the students of the School are female.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M., D.A. and N.P.; methodology, D.M., N.P. and D.A.; software, G.A.; validation, G.A. and D.A.; formal analysis, G.A., D.M. and D.A.; investigation, N.P., D.M. and D.A.; resources, D.M. and N.P.; data curation, N.P. and D.M.; writing–original draft preparation, D.M. and D.A.; Writing–review & editing, D.M., D.A. and G.A.; visualization, G.A.; Project administration, D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Western Macedonia (date of approval: 10 May 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

The questionnaire did not require the completion of a separate participant information sheet or consent form but clearly indicated that all questionnaire respondents give informed consent to the study. Respondents were informed about the course and nature of the survey. The survey was voluntary and confidential.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Braun-Lewensohn, O.; Abu-Kaf, S.; Kalagy, T. Hope and resilience during a pandemic among three cultural groups in Israel: The second wave of Covid-19. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everett, J.A.C.; Colombatto, C.; Chituc, V.; Brady, W.J.; Crockett, M. The effectiveness of moral messages on public health behavioral intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic. PsyArXiv, 2020; 1–23, Preprints. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfattheicher, S.; Nockur, L.; Böhm, R.; Sassenrath, C.; Petersen, M.B. The emotional path to action: Empathy promotes physical distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piovani, D.; Christodoulou, M.N.; Hadjidemetriou, A.; Pantavou, K.; Zaza, P.; Bagos, P.G.; Bonovas, S.; Nikolopoulos, G.K. Effect of early application of social distancing interventions on COVID-19 mortality over the first pandemic wave: An analysis of longitudinal data from 37 countries. J. Infect. 2021, 82, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT). (n.d.). Coronavirus Government Response Tracker. Available online: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker#data (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Moris, D.; Schizas, D. Lockdown during COVID-19: The Greek success. In Vivo 2020, 34 (Suppl. S3), 1695–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farsalinos, K.; Poulas, K.; Kouretas, D.; Vantarakis, A.; Leotsinidis, M.; Kouvelas, D.; Docea, A.O.; Kostoff, R.; Gerotziafas, G.T.; Antoniou, M.N.; et al. Improved strategies to counter the COVID-19 pandemic: Lockdowns vs. primary and community healthcare. Toxicol. Rep. 2021, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardikiotis, A.; Malinaki, E.; Charisiadis-Tsitlakidis, C.; Protonotariou, A.; Archontis, S.; Lampropoulou, A.; Maraki, I.; Papatheodorou, K.; Zafeiriou, G. Emotional and cognitive responses to COVID-19 information overload under lockdown predict media attention and risk perceptions of COVID-19. J. Health Commun. 2021, 26, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Mathieu, E.; Rodés-Guirao, L.; Appel, C.; Giattino, C.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Hasell, J.; MacDonald, B.; Beltekian, D.; Dattani, S.; et al. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19); Our World in Data; The University of Oxford, Global Change Data Lab: Oxford, UK, 28 November 2021; Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Masten, A.S.; Reed, M.G.J. Resilience in development. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 74–88. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, S. Psychological and social aspects of resilience: A synthesis of risks and resources. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2003, 5, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michail, D.; Christou, A. Diasporic youth identities of uncertainty and hope: Second-generation Albanian experiences of transnational mobility in an era of economic crisis in Greece. J. Youth Stud. 2016, 19, 957–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepou, L.E.; Economou, M.; Skali, T.; Papageorgiou, C. From economic crisis to the COVID-19 pandemic crisis: Evidence from a mental health helpline in Greece. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2010, 271, 407–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planchuelo-Gόmez, A.; Odriozola-Gonzáles, P.; Irurtia, M.J.; de Luis Garzía, R. Longitudinal evaluation of the psychological impact of the COVID-19 crisis in Spain. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, M.; Robinson, E. Psychological distress and adaptation to the COVID-19 crisis in the United States. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 136, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M. Psychological stress responses to COVID-19 and adaptive strategies in China. World Dev. 2020, 136, 105107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odriozola-González, P.; Planchuelo-González, Á.; Irurtia, M.J.; de Luis-García, R. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown among students and workers of a Spanish university. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patsali, M.E.; Priskila, D.; Mousa, D.P.V.; Papadopoulou, E.V.K.; Papadopoulou, K.K.K.; Kaparounaki, C.K.; Diakogiannis, I.; Fountoulakis, K.N. University students’ changes in mental health status and determinants of behavior during the COVID-19 lockdown in Greece. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 292, 113298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stathopoulou, T.; Mouriki, A.; Papaliou, O. Student Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Greece. Results from the C19 ISWS Survey, Report (v.1); National Centre for Social Research: Athens, Greece, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, F.; Bianchi, G.; Song, D. The Long-Term Impact of the COVID-19 Unemployment Shock on Life Expectancy and Mortality Rates; Working Paper 28304; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Job, E.; Steptoe, D. Abuse, self-harm and suicidal ideation in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Psychiatry 2021, 217, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, A.; Efstathiou, V.; Yotsidi, V.; Pomini, V.; Michopoulos, I.; Markopoulou, E.; Papadopoulou, M.; Tsigkaropoulou, E.; Kalemi, G.; Tournikioti, K.; et al. Suicidal ideation during COVID-19 lockdown in Greece: Prevalence in the community, risk, and protective factors. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 297, 113713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountoulakis, K.N.; Apostolidou, M.K.; Atsiova, M.B.; Filippidou, A.K.; Florou, A.K.; Gousiou, D.S.; Katsara, A.R.; Mantzari, S.N.; Padouva-Markoulaki, M.; Papatriantafyllou, E.I.; et al. Self-reported changes in anxiety, depression, and suicidality during the COVID-19 lockdown in Greece. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulakidakos, S. Media events, speech events and propagandistic techniques of legitimation: A multimodal analysis of the Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis’ public addresses on the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.; Yi, Y. On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson/Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus for Windows 7.31; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, R. Parametric measures of effect size. In Handbook of Research Synthesis; Cooper, H., Hedges, L.V., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 231–244. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, M. Risk and protective factors in the development of psychopathology. In Psychological Resilience and Protective Mechanisms; Rolf, J., Masten, A.S., Ciccetti, D., Nuechterlein, K.H., Weintraub, A.S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 181–214. [Google Scholar]

- Haidt, J. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion; Pantheon/Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Buss, D. Evolutionary Psychology: The New Science of the Mind, 5th ed.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, C.; White, M.G. The anthropology of emotions. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1986, 15, 405–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, I. Fears, Phobias, and Rituals: Panic, Anxiety, and Their Disorders; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi, K. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time, 2nd ed.; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Spinoza, B. A Political Treatise (Tractatus Politicus); 1670/1901, (trans. from the Latin by R.H.M. Elwes, 1901). Kindle Edition 2016; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: North Charleston, SC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, R.; Socci, V.; Talevi, D.; Mensi, S.; Niolu, C.; Pacitti, F.; Di Marco, A.; Rossi, A.; Siracusano, A.; Di Lorenzo, G. COVID-19 Pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alleaume, C.; Verger, P.; Peretti-Watel, P. Τhe COCONEL Group Psychological support in general population during the COVID-19 lockdown in France: Needs and access. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, F.; Léger, D.; Fressard, L.; Peretti-Watel, P.; Verger, P. Covid-19 health crisis and lockdown associated with high level of sleep complaints and hypnotic uptake at the population level. J. Sleep Res. 2020, 30, 13119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Fang, Z.; Hou, G.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Dong, J.; Zheng, J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; McIntyre, R.S.; Choo, F.N.; Tran, B.; Ho, R.; Sharma, V.K.; et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).