Accelerating Cultural Dimensions at International Companies in the Evidence of Internationalisation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

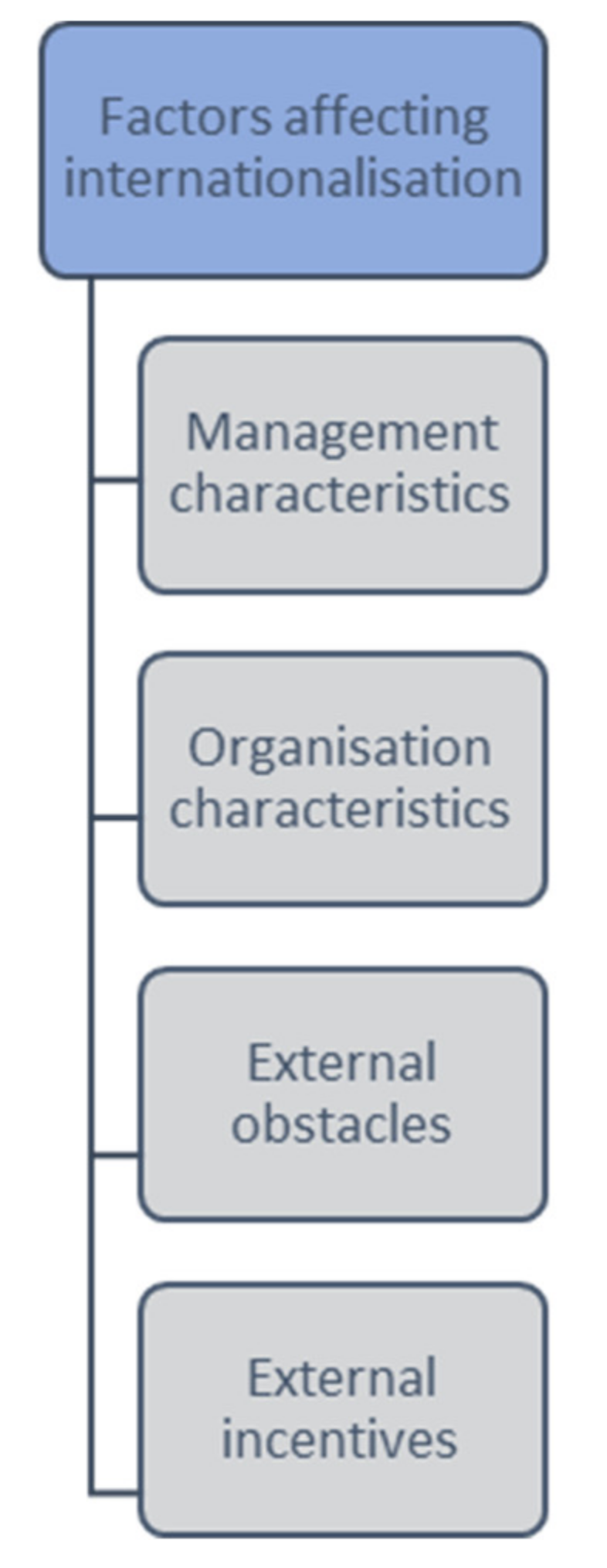

2.1. Factors Affecting Internationalisation

- Financial lack of barriers or insufficiency

- Informational barriers

- Inefficiencies of human resource management

- Pressures on adapting the elements of the company’s product and pricing strategy

- Distribution, logistics, transportation costs and promotion aspects of in foreign markets

- Lack of export training and government help [38]

2.2. A Holistic Approach to Internalisation

2.3. International Business Management

2.4. Cultural Dimensions of Hofstede

| Cultural Dimension by Hofstede | Authors |

|---|---|

| Power distance | [5,12,14,15,51,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66] |

| Individualism/ Collectivism | [5,12,14,15,53,54,56,57,58,59,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75] |

| Masculinity/ Femininity | [5,12,14,15,53,54,56,57,58,59,65,66,76] |

| Uncertainty Avoidance Uncertainty Tolerance | [5,12,14,15,53,54,56,57,59,65,66,67,69] |

| Long-term Orientation/ Short-term Orientation | [5,14,15,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,65,66,76,77,78] |

| Indulgence/ Restraint | [14,15,53,54,57,65,66,67] |

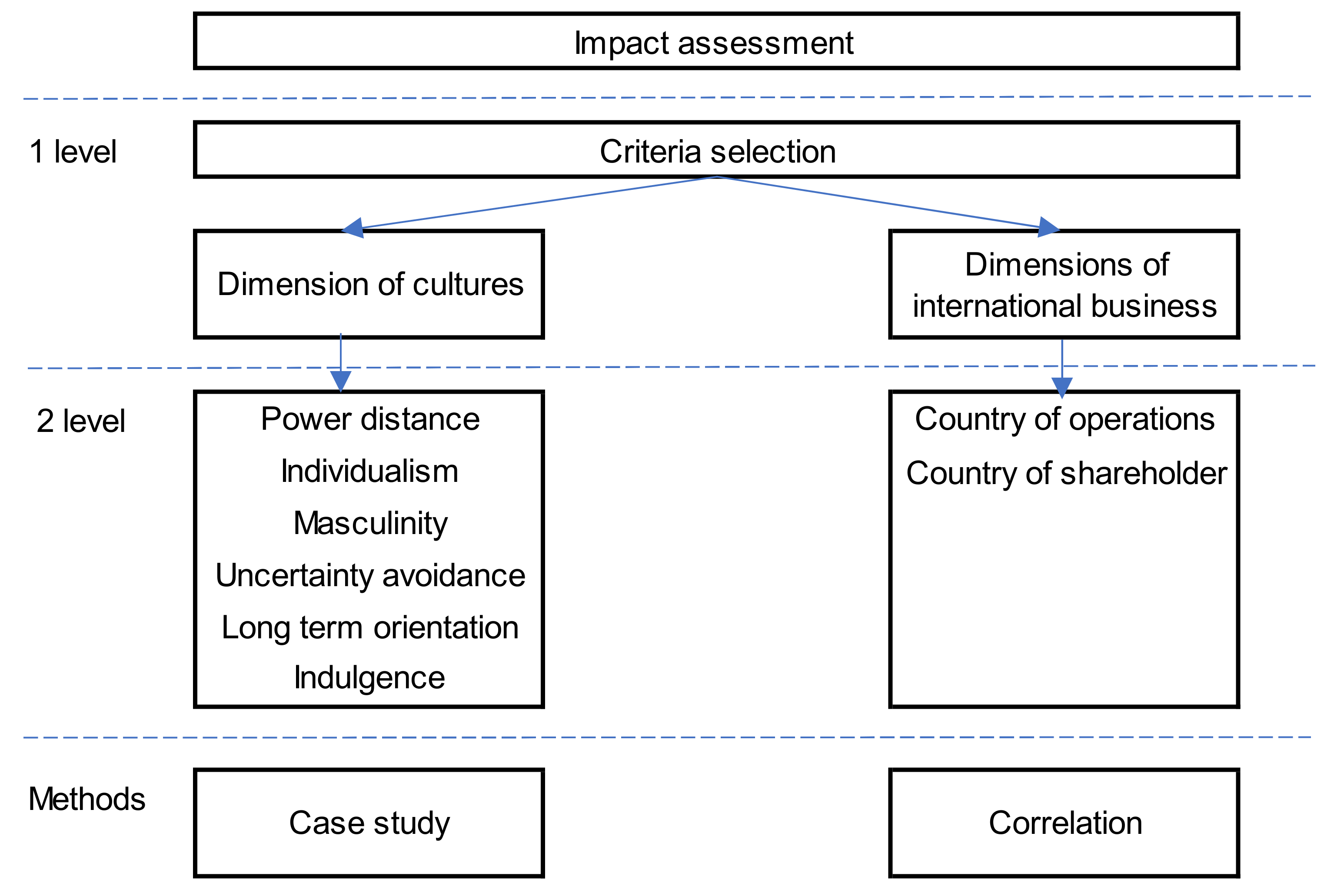

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

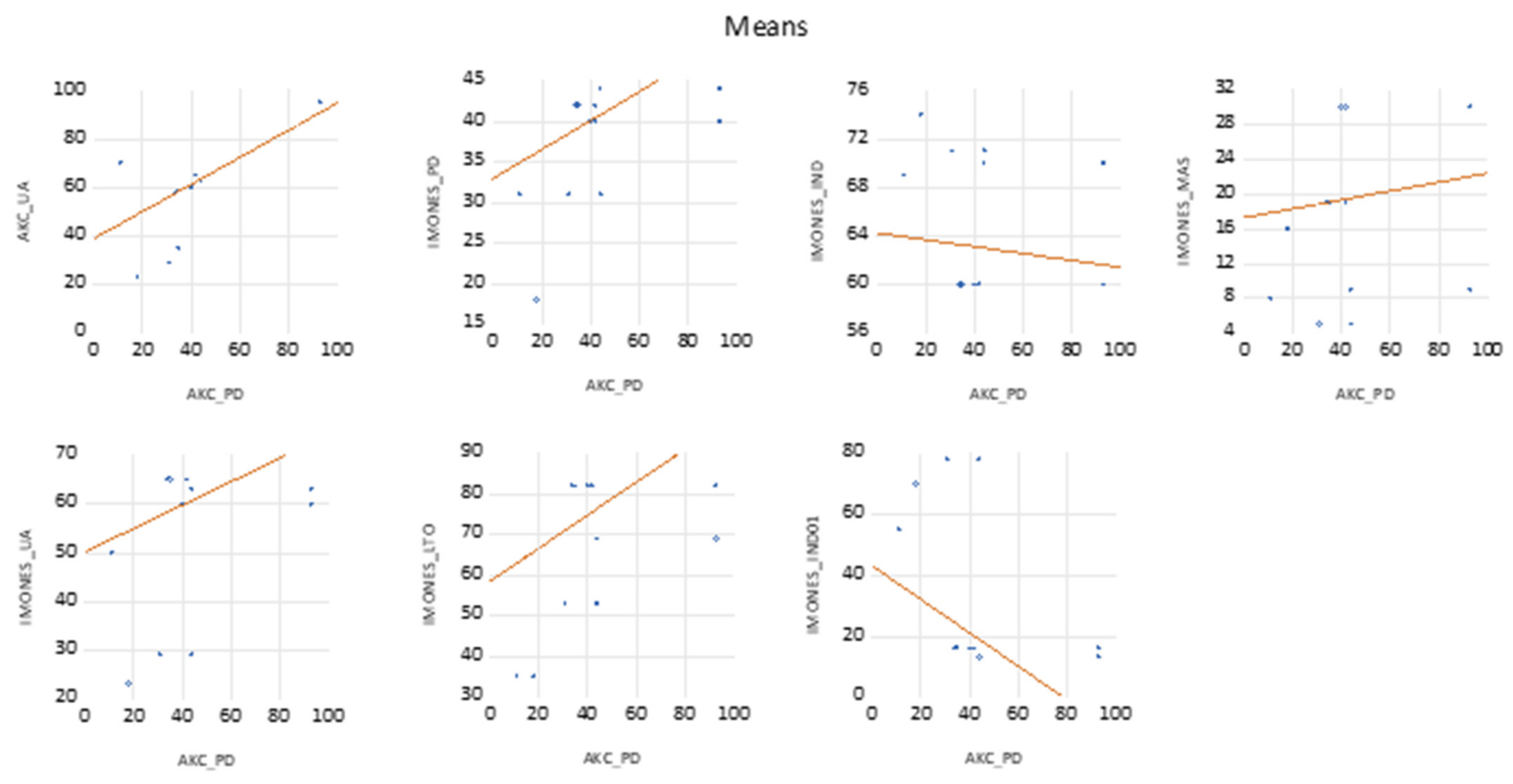

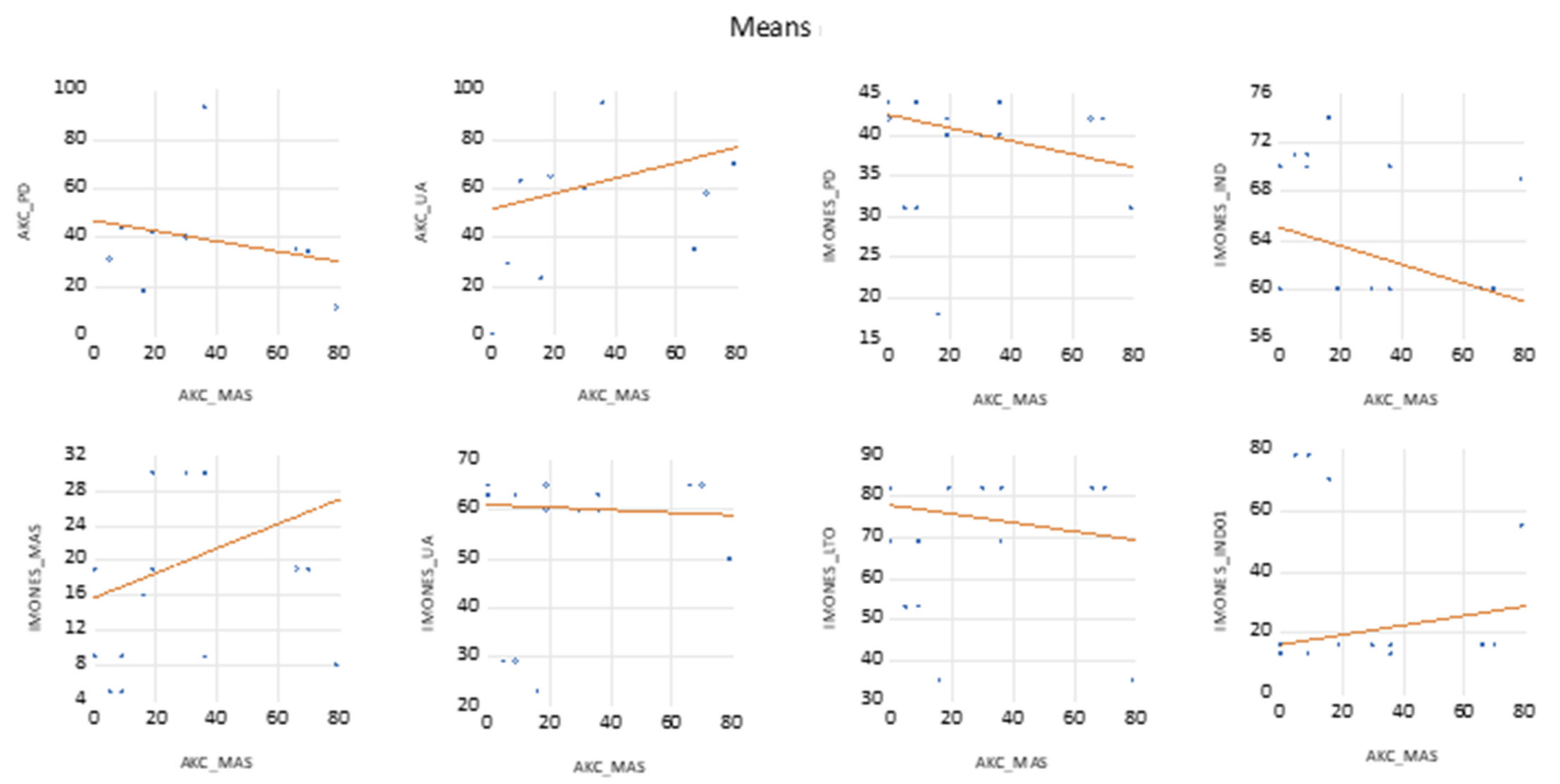

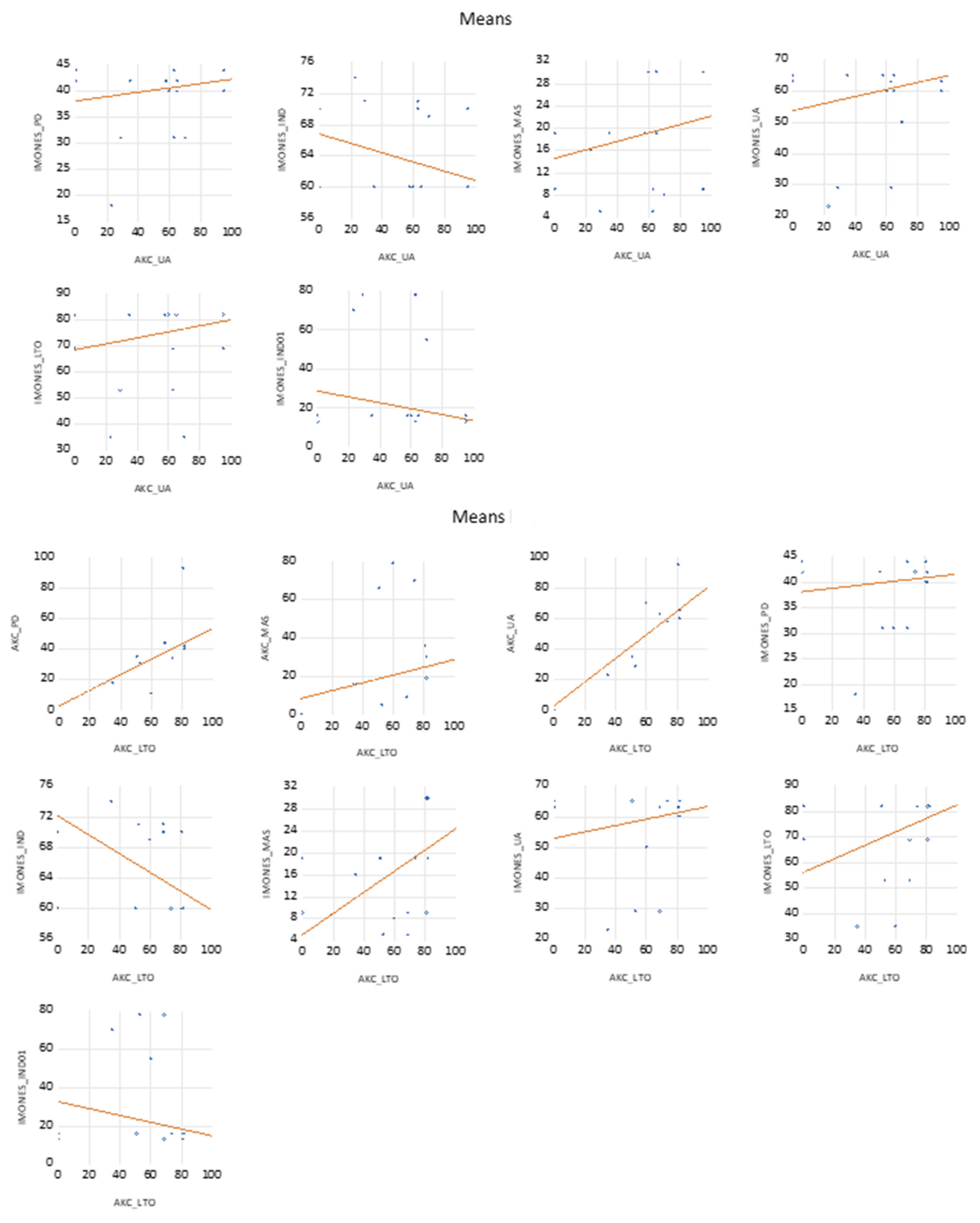

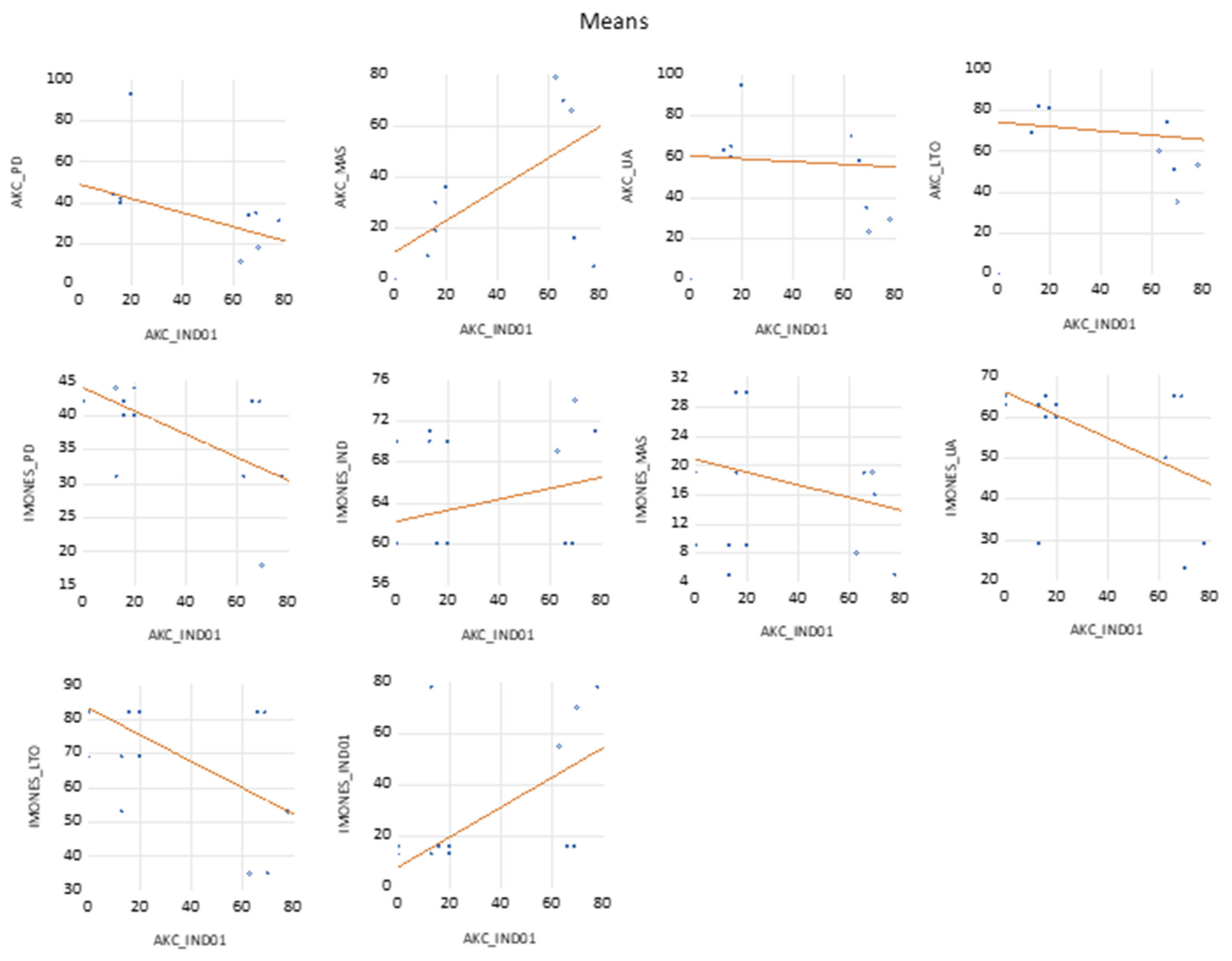

4.1. Relationship between MNE Cultural Dimensions

- -

- shareholder power distance with company power distance,

- -

- shareholder power distance with company uncertainty avoidance

- -

- shareholder power distance with long-term company orientation,

- -

- shareholder individualism with company uncertainty avoidance,

- -

- shareholder individualism with long-term company orientation,

- -

- shareholder individualism with company indulgence,

- -

- shareholder masculinity with company masculinity.

- -

- shareholder power distance with company indulgence,

- -

- shareholder individualism with company power distance,

- -

- shareholder masculinity with company power distance,

- -

- shareholder masculinity with company individualism.

4.2. Regression Matrix

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Apetrei, A.; Kureshi, N.I.; Horodnic, I.A. When culture shapes international business. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1519–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraris, A.; Giachino, C.; Ciampi, F.; Couturier, J. R&D internationalization in medium-sized firms: The moderating role of knowledge management in enhancing innovation performances. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frensch, R.; Horvath, R.; Huber, S. Openness effects on the rule of law: Size and patterns of trade. Int. Rev. Law Econ. 2021, 68, 106027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara, J.; Roman, P.; Surichaqui, R.; Vicente-Ramos, W. Internal factors that stimulate the internationalization of companies in Peru’s jewellery sector. Bus. Theory Pract. 2020, 21, 792–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Hao, A. Understanding the impact of national culture on firms’ benefit-seeking behaviours in international B2B relationships: A conceptual model and research propositions. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çela, A.; Hysa, E.; Voica, M.C.; Panait, M. Internationalization of Large Companies from Central and Eastern Europe or the Birth of New Stars. Sustainability 2022, 14, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che Senik, Z.; Isa, R.M.; Sham, R.M.; Ayob, A.H. A model for understanding SMEs internationalization in emerging economies. J. Pengur. 2014, 41, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissak, T.; Zhang, X. Which Factors Affect the Internationalization of Chinese Firms? J. Impacts Emerg. Econ. Firms Int. Bus. 2012, 3, 48–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, T. Managing Cultural Diversity at Work. In Essential Management Skills for Pharmacy and Business Managers; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2013; pp. 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębczyńska, A. Cultural Differences and Polish-Chinese Business Relations in Practice. J. Corp. Responsib. Leadersh. 2018, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drogendijk, R.; Slangen, A. Hofstede, Schwartz, or managerial perceptions? The effects of different cultural distance measures on establishment mode choices by multinational enterprises. Int. Bus. Rev. 2006, 15, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences International Differences in Work-Related Values, Abridged ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Culture and Organizations. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2010, 10, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2011, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agodzo, D. Six Approaches to Understanding National Cultures: Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions. November 2014; pp. 1–11. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284732557 (accessed on 5 December 2021). [CrossRef]

- Fuentelsaz, L.; Garrido, E.; Maicas, J.P. The effect of informal and formal institutions on foreign market entry selection and performance. J. Int. Manag. 2020, 26, 100735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogrebnyakov, N.; Maitland, C.F. Institutional distance and the internationalization process: The case of mobile operators. J. Int. Manag. 2011, 17, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenk, C.; Eiche, J.; Kabst, R. The Moderating Impact of Informal Institutional Distance and Formal Institutional Risk on SME Entry Mode Choice. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 330–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Johanson, M. International opportunity networks. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 70, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J.; Johanson, M. Speed and synchronization in foreign market network entry: A note on the revisited Uppsala model. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2021, 52, 1628–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J.; Mattsson, L.-G. Internationalisation in industrial systems—A network approach. In Understanding Business Markets: Interaction, Relationships and Networks; Ford, D., Ed.; Academic Press Limited: London, UK, 1988; pp. 468–486. [Google Scholar]

- Johanson, J.; Vahlne, J.-E. The mechanism of internationalisation. Int. Mark. Rev. 1990, 7, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkkeli, L.; Kuivalainen, O.; Saarenketo, S.; Puumalainen, K. Institutional environment and network competence in successful SME internationalisation. Int. Mark. Rev. 2019, 36, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinic, I.; Forza, C. Rapid internationalization of traditional SMEs: Between gradualist models and born globals. Int. Bus. Rev. 2012, 21, 694–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinic, I.; Sarasvathy, S.D.; Forza, C. “Expect the unexpected”: Implications of effectual logic on the internationalization process. Int. Bus. Rev. 2014, 23, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almodovar, P.; Rugman, A.M. Testing the revisited Uppsala model: Do insiders improve international performance? Int. Mark. Rev. 2015, 32, 686–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najera, M. Managing Mexican workers: Implications of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. J. Int. Bus. Res. 2008, 7, 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Bond, M.H. Hofstede’s Culture Dimensions: An Independent Validation Using Rokeach’s Value Survey; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Centre, L.I. The Importance of Cultural Differences in International Business; WSB University in Wrocław: Wrocław, Poland, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Che Rusuli, M.S.; Tasmin, R.; Takala, J. The impact of the structural approach on knowledge management practice (KMP) at Malaysian university libraries. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2012, 6, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Decker, J.C. Relationship Between Cultural Distance and Entry Mode by Western European Multinational Enterprises into Eastern Asia. Ph.D. Thesis, Grand Canyon University, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Özdemir, E.; Altintaş, M.H.; Kiliç, S. The Effects of the Degree of Internationalisation on Export Performance. İşletme Ve Ekon. Araştırmaları Derg. 2017, 8, 611–626. [Google Scholar]

- Matić, J.L. Cultural differences in employee work values and their implications for management. J. Contemp. Manag. Issues 2008, 13, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, N.J. A Study of the Internationalisation of Australian Manufacturing Firms. Ph.D. Thesis, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, R. A holistic approach to internationalisation. Int. Bus. Rev. 2001, 10, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronfeldner, M. The Routledge Handbook of Dehumanization; Issue January 2016; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milana, E.; Maldon, I. Managerial characteristics and its impact on organisational performance: Evidence from Syria. Bus. Theory Pract. 2015, 16, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glossary for Barriers to SME Access to International Markets. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/ (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Kaynak, E.; Kothari, V. Export behaviour of small and medium-sized manufacturers: Some policy guidelines for international marketers. Manag. Int. Rev. 1984, 24, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, J.H. The eclectic paradigm as an envelope for economic and business theories of MNE activity. Int. Bus. Rev. 2000, 9, 163–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iammarino, S.; McCann, P.; Ortega-Argilés, R. International business, cities and competitiveness: Recent trends and future challenges. Compet. Rev. 2018, 28, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunday, Ö.; Şengüler, E.P. A Study on Factors Affecting Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 972–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casson, M. Coase and international business: The origin and development of internalisation theory. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2014, 36, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casson, M.C. The Theory of International Business: Economic Models and Methods, Basingstoke; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Casson, M. The theory of international business: The role of economic models. Manag. Int. Rev. 2018, 58, 363–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, U.; Forsgren, M.; Holm, U. Balancing subsidiary influence in the federative MNC: A business network view. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2007, 38, 802–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouquet, C.; Birkinshaw, J. How global strategies emerge: An attention perspective. Int. Strategy J. 2011, 1, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, M.; Dirks, K.T.; Nickerson, J.A. Micro foundations of strategic problem formulation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.K.; Pindyck, R.S. Investment under Uncertainty; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke, A.; Yuan, W. Subsidiary autonomous activities in multinational enterprises: A transaction cost perspective. Manag. Int. Rev. 2005, 45, 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fengfan, M. Managing Cultural Differences in International Business Negotiations. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Innovation, Wuhan, China, 20–22 November 2015; pp. 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Borneman, J. Public Apologies as Performative Redress. SAIS Rev. Int. Aff. 2005, 25, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.M.N. Negotiation for the Middle East: A Comparative Study of Cultures and the Construction of a Negotiation Framework for PORTUGUESE in Kuwait. 2017. Available online: https://repositorio.iscte-iul.pt/bitstream/10071/15806/1/pedro_neves_ferreira_diss_mestrado.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Warter, I.; Alexandru, U.; Cuza, I.; Warter, L.; Alexandru, U.; Cuza, I. Intercultural Negotiation in Mergers and Acquisitions. The Integration of the Cultural Dimension into the Negotiation Domain. July 2015; pp. 74–86. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277919151 (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Hofstede, G.J.; Jonker, C.M.; Verwaart, T.; Yorke-Smith, N. The Lemon Car Game Across Cultures: Evidence of Relational Rationality. Group Decis. Negot. 2019, 28, 849–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Huang, S.; Alexander, W.R.J. Do national cultural traits affect comparative advantage in cultural goods? Sustainability 2017, 9, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R.; Vauclair, C.M.; Fontaine, J.R.J.; Schwartz, S.H. Are individual-level and country-level value structures different? testing hofstede’s legacy with the Schwartz value survey. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2010, 41, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daňková, A.; Droppa, M. The Impact of National Culture on Working Style of Slovak Managers. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 34, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Herold, D.M. Cultural relevance in corporate sustainability management: A comparison between Korea and Japan. Asian J. Sustain. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. How Power Distance Interacts with Culture and Status to Explain Intra- and Intercultural Negotiation Behaviors: A Multilevel Analysis. Negot. Confl. Manag. Res. 2019, 12, 192–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhu, L.; Cionea, I.A. What Makes Some Intercultural Negotiations More Difficult Than Others? Power Distance and Culture-Role Combinations. Commun. Res. 2019, 46, 555–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Han, X.; Li, J. Supervisor Narcissism and Employee Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model of Affective Organizational Commitment and Power Distance Orientation. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 43, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, A.; Ayoko, O.B.; Amoo, N.; Menke, C. The relationship between cultural values, cultural intelligence and negotiation styles. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, R.; Skandrani, H. Effects of Individualism and Power Distance on Business Student Judgments of Various Negotiating Tactics. J. Int. Manag. Stud. 2014, 14, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilaplana, A.; Gentner, A.; Favart, C. The Role of Communication Tools in the Early-phase Design Process. Int. J. Affect. Eng. 2019, 18, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, N.L. ScholarWorks @ GVSU. The Impact of Culture on Business Negotiations The Impact of Culture on Business Negotiations. Honor. Proj. 2021, 839, 13. Available online: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/honorsprojects/839 (accessed on 11 December 2021).

- Masuda, T.; Ito, K.; Lee, J.; Suzuki, S.; Yasuda, Y.; Akutsu, S. Culture and Business: How Can Cultural Psychologists Contribute to Research on Behaviors in the Marketplace and Workplace? Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waistell, J. Individualism and collectivism in business school pedagogy: A research agenda for internationalising the home management student. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2011, 30, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogihara, Y. The Rise in Individualism in Japan: Temporal Changes in Family Structure, 1947–2015. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2018, 49, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiah, O.; Syukurriah, I.; Fauziah, N. Individualism-Collectivism and Its Influence on Positive Organizational Behavior: An Exploratory Study. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 2011, 21, 1193–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Ralston, D.A.; Egri, C.P.; Furrer, O.; Kuo, M.H.; Li, Y.; Wangenheim, F.; Dabic, M.; Naoumova, I.; Shimizu, K.; de la Garza Carranza, M.T.; et al. Societal-Level Versus Individual-Level Predictions of Ethical Behavior: A 48-Society Study of Collectivism and Individualism. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Minh, H. The Impacts of Individualism/Collectivism on Consumer Decision-Making Styles: The Case of Finnish and Vietnamese Mobile Phone Buyers 2015. Available online: https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/103353/TUAS-Bachelor-Thesis-2015_-Hoang-Minh.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Mockaitis, A.I.; Rose, E.L.; Zettinig, P. The power of individual cultural values in global virtual teams. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 2012, 12, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beugelsdijk, S.; Kostova, T.; Kunnst, V.E.; Spadafora, E.; Essen, M. Cultural Distance and Firm Internationalization: A Meta-Analytical Review and Theoretical. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 89–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.J.; Jonker, C.M.; Verwaart, T. Modelling culture in trade: Uncertainty avoidance. In Proceedings of the 2008 Spring Simulation Multiconference, SpringSim’08, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 14–17 April 2008; pp. 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huettinger, M. Cultural dimensions in business life: Hofstede’s indices for Latvia and Lithuania. Balt. J. Manag. 2008, 3, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Qiao, X. Indulgence and long-term orientation influence prosocial behavior at national level. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkin, R.S. Cultural Long-Term Orientation and Facework Strategies. Atl. J. Commun. 2004, 12, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Hernandez, J.G. International and Cultural Implications on Internationalization Analysis of Multinational Firms. J. Econ. Financ. Stud. 2015, 3, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Comer, F.; Mula, J.; Díaz-Madroñero, M.; Grillo, H. Optimising the analysis stage in international manufacturing operations. S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. 2021, 32, 124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, B.; Sefalafala, M.R. The influence of entrepreneurial intensity and capabilities on internationalisation and firm performance. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2015, 18, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhao, J.H.; Du, J. The internationalisation speed of e-commerce companies: An empirical analysis. Int. Mark. Rev. 2005, 22, 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cultural Compass. Available online: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/product/compare-countries/ (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Nasdaq. Nasdaq Database. Available online: https://www.nasdaq.com/ (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Schäffler, T.; Foehr, M.; Lüder, A.; Supke, K. Engineering process evaluation: Evaluation of the impact of internationalisation decisions on the efficiency and quality of engineering processes. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics, Taipei, Taiwan, 28–31 May 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Reuber, A.R.; Tippmann, E.; Monaghan, S. Global scaling as a logic of multinationalization. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2021, 52, 1031–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.; Hooley, G.; Loveridge, R. (Eds.) Internationalisation: Process, Context and Markets; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lindner, T.; Puck, J.; Doh, J. Hierarchical modelling in international business research: Patterns, problems, and practical guidelines. J. World Bus. 2021, 56, 101–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Si, S. The influence of exploration and exploitation on born globals’ speed of internationalisation. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisch, J.H. Investment in new foreign subsidiaries under the receding perception of uncertainty. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2008, 39, 370–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, D. Measuring the degree of internationalisation of a firm: A reply. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1996, 27, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, S.; Eriksson, K. Mutual commitment and experiential knowledge in a mature international business relationship. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2002, 11, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winch, G.W.; Bianchi, C. Drivers and dynamic processes for SMEs going global. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2006, 13, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Navare, J.; Jin, Z. Business model innovation: How the international retailers rebuild their core business logic in a new host country. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, B.; Kulatilaka, N. Operating flexibility, global manufacturing, and the option value of a worldwide network. Manag. Sci. 1994, 40, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majocchi, A.; Dalla Valle, L.; D’Angelo, A. Internationalization, cultural distance and country characteristics: A Bayesian analysis of SMEs financial performance. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2015, 16, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kamakura, W.A.; Ramón-Jerónimo, M.A.; Gravel, J.D.V. A dynamic perspective to the internationalization of small-medium enterprises. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbe, J.N.; Richter, N.F. Causal analysis of the internationalisation and performance relationship based on neural networks—Advocating the transnational structure. J. Int. Manag. 2009, 15, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pheng, L.S.; Hongbin, J. Analysing ownership, locational and internalisation advantages of Chinese construction MNCs using rough sets analysis. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2006, 24, 1149–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisch, J.H. Optimal dispersion of R&D activities in multinational corporations with a genetic algorithm. Res. Policy 2003, 32, 1381–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, A.; Herrero, Á. Selecting features that drive the internationalisation of Spanish firms. Cybern. Syst. 2019, 50, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasayat, A.K.; Bhowmick, B. An evolutionary algorithm-based framework for determining crucial features contributing to the success of a start-up. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Technology & Engineering Management Conference-Europe (TEMSCON-EUR), Online. 17–20 May 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lorentz, H. Production locations for the internationalising food industry: A case study from Russia. Br. Food J. 2008, 110, 310–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.S.; Mahdiraji, H.A.; Azari, M.; Hajiagha, S.H.R. Causal modelling of failure fears for international entrepreneurs in the tourism industry: A hybrid Delphi-DEMATEL based approach. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemad, H.; Gurau, C.; Dana, L.P. International entrepreneurship research agendas evolving: A longitudinal study using the Delphi method. J. Int. Entrep. 2021, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettinig, P.; Vincze, Z. Developing the international business curriculum: Results and implications of a Delphi study on the futures of teaching and learning in international business. J. Teach. Int. Bus. 2008, 19, 109–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettinig, P.; Vincze, Z. The domain of international business: Futures and future relevance of international business. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2011, 53, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.; Leo-Paul, D.; Jones, M.V. Toward new horizons: The internationalization of entrepreneurship. J. Int. Entrep. 2003, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, R.D.; Wilson, H.I. The network model of internationalization and experiential knowledge. Int. Bus. Rev. 2003, 12, 697–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzychenko, O. Cross-cultural entrepreneurial competence in identifying international business opportunities. Eur. Manag. J. 2008, 26, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Literature on Internationalisation | Literature on Culture Aspects | Hofstede’s Culture Dimensions | Thematic of Hofstede’s Culture Dimensions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power Distance | Individualism | Masculinity | Uncertainty | Long Term Orientation | Indulgence | Under the Literature on Internationalisation | |||

| 1994–1998 | 2460 | 360 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 10 | 0 | 21 |

| 1999–2003 | 5160 | 487 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 103 | 141 | 3 | 252 |

| 2004–2008 | 10,800 | 1790 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 245 | 453 | 2 | 717 |

| 2009–2013 | 125,000 | 2040 | 40 | 58 | 4 | 287 | 843 | 3 | 1235 |

| 2014–2018 | 254,000 | 3870 | 7 | 79 | 4 | 329 | 656 | 3 | 1078 |

| 2019–2021 | 250,000 | 3600 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 333 | 676 | 4 | 1033 |

| Total | 647,420 | 12,147 | 66 | 157 | 16 | 1303 | 2779 | 15 | 4336 |

| % | 100% | 1,9% | 0.67% | ||||||

| Model Type | Model Technique | Solution Method | Researching Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mathematical programming method | Single objective | Linear programming | [80] |

| Multiple objectives | Mixed-integer linear programming | [81] | |

| Multiple regression | [82] | ||

| [83] | |||

| [84] | |||

| Analysis of hierarchical regression | [85] | ||

| [86] | |||

| Deterministic dynamic programming | [87] | ||

| Causal models | Causality identification methods | Non-linear programming | [88] |

| Causal effect modelling | [89] | ||

| Causal loop diagrams | [90] | ||

| [91] | |||

| Heuristic methods | Simple heuristic | Simulated annealing heuristics | [92] |

| Artificial intelligence techniques | Markov chains | [93] | |

| [94] | |||

| Bayesian network modelling | [95] | ||

| Rough sets | [96] | ||

| Metaheuristic | Particle swarm optimisation | [97] | |

| Genetic Algorithm | [98] | ||

| [99] | |||

| Analytical models | Multi-criteria decision-making | AHP | [100] |

| DEMATEL | [101] | ||

| Systematic models | Delphi method | [102] | |

| [103] | |||

| [104] | |||

| Network model | [105] | ||

| [106] |

| Countries | Power Distance | Individualism | Masculinity | Uncertainty Avoidance | Long Term Orientation | Indulgence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | 18 | 74 | 16 | 23 | 35 | 70 |

| Norway | 31 | 69 | 8 | 50 | 35 | 55 |

| Sweden | 31 | 71 | 5 | 29 | 53 | 78 |

| Estonia | 40 | 60 | 30 | 60 | 82 | 16 |

| Latvia | 44 | 70 | 9 | 63 | 69 | 13 |

| Lithuania | 42 | 60 | 19 | 65 | 82 | 16 |

| Dimensions of Cultural Difference | Shareholder POWER Distance | Shareholder Individualism | Shareholder Masculinity | Shareholder Uncertainty Avoidance | Shareholder Long Term Orientation | Shareholder Indulgence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company Power distance | P | N | N | P | P | N |

| Company Individualism | N | P | N | N | N | P |

| Company Masculinity | P | S | P | P | P | N |

| Company Uncertainty avoidance | P | P | N | P | P | N |

| Company Long-Term Orientation | P | P | N | P | P | N |

| Company Indulgence | N | P | P | N | N | P |

| Correlation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant Correlation Coeficients | AKC_PD | AKC_IND | AKC_MAS | AKC_UA |

| AKC_PD | −0.28 | 0.65 | ||

| AKC_UA | 0.30 | |||

| IMONES_PD | 0.49 | −0.47 | −0.31 | |

| IMONES_IND | −0.26 | |||

| IMONES_MAS | 0.28 | |||

| IMONES_UA | 0.34 | 0.51 | ||

| IMONES_LTO | 0.41 | 0.64 | ||

| IMONES_IND01 | −0.44 | 0.37 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leonavičienė, E.; Burinskienė, A. Accelerating Cultural Dimensions at International Companies in the Evidence of Internationalisation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031524

Leonavičienė E, Burinskienė A. Accelerating Cultural Dimensions at International Companies in the Evidence of Internationalisation. Sustainability. 2022; 14(3):1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031524

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeonavičienė, Edita, and Aurelija Burinskienė. 2022. "Accelerating Cultural Dimensions at International Companies in the Evidence of Internationalisation" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031524

APA StyleLeonavičienė, E., & Burinskienė, A. (2022). Accelerating Cultural Dimensions at International Companies in the Evidence of Internationalisation. Sustainability, 14(3), 1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031524