The Social Dimension of Security: The Dichotomy of Respondents’ Perceptions during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- RQ1: Do the respondents think that their financial situation deteriorated during the period under analysis?

- RQ2: Do households fear poverty during the pandemic?

- RQ3: Do the respondents think their employment situation is secure?

- RQ4: What is the respondents’ level of uncertainty about the future situation of their households and the socioeconomic situation in Poland?

2. Materials and Methods

- Stage 1. Creation of a hierarchical structure concerning the sense of social insecurity.

- Stage 2. Normalisation and aggregation of the variable values.

- Stage 3. Linear ordering and typological classification of objects according to the synthetic measure value.

3. Results

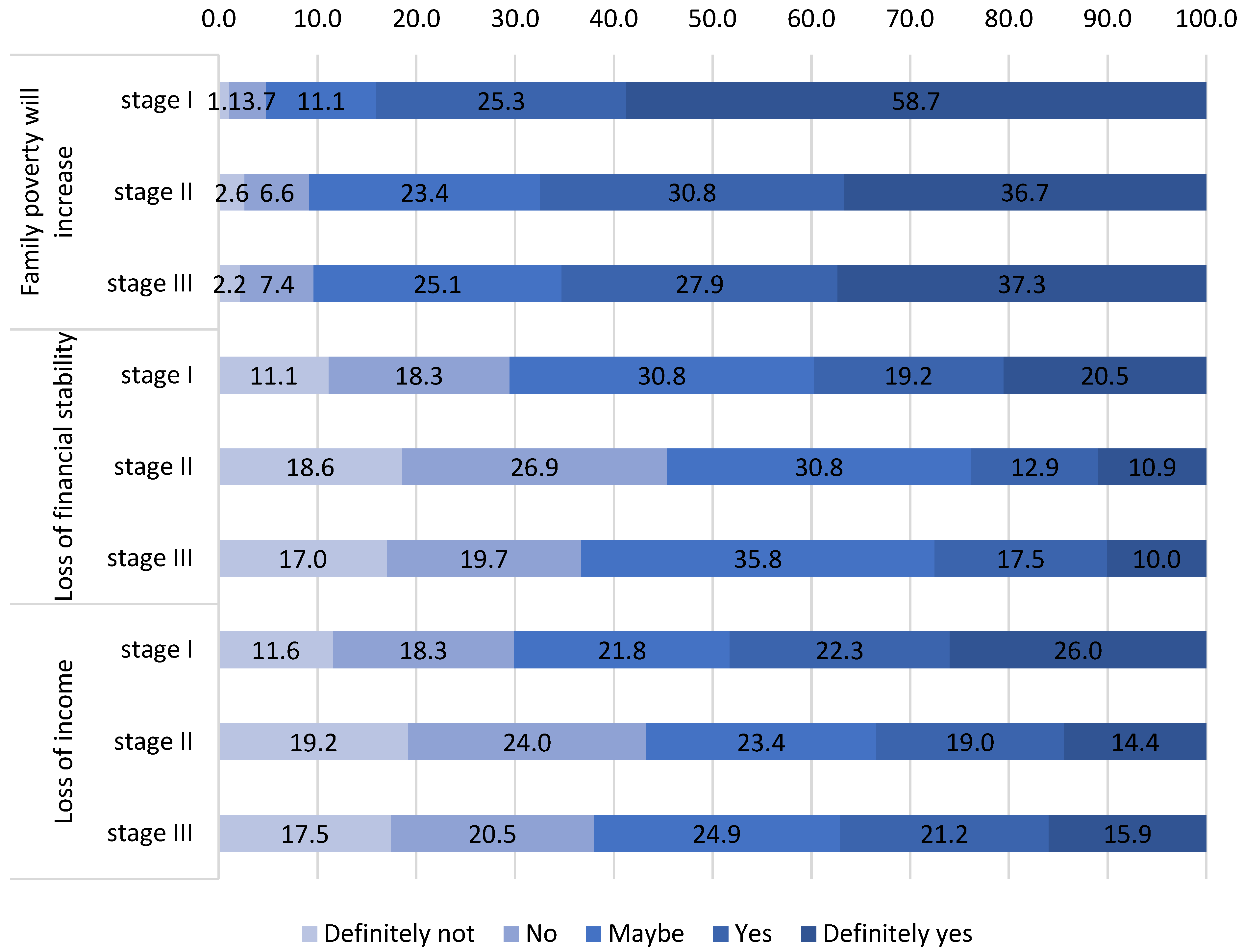

3.1. Subjective Assessment of Social Security of Households during the COVID-19 Pandemic

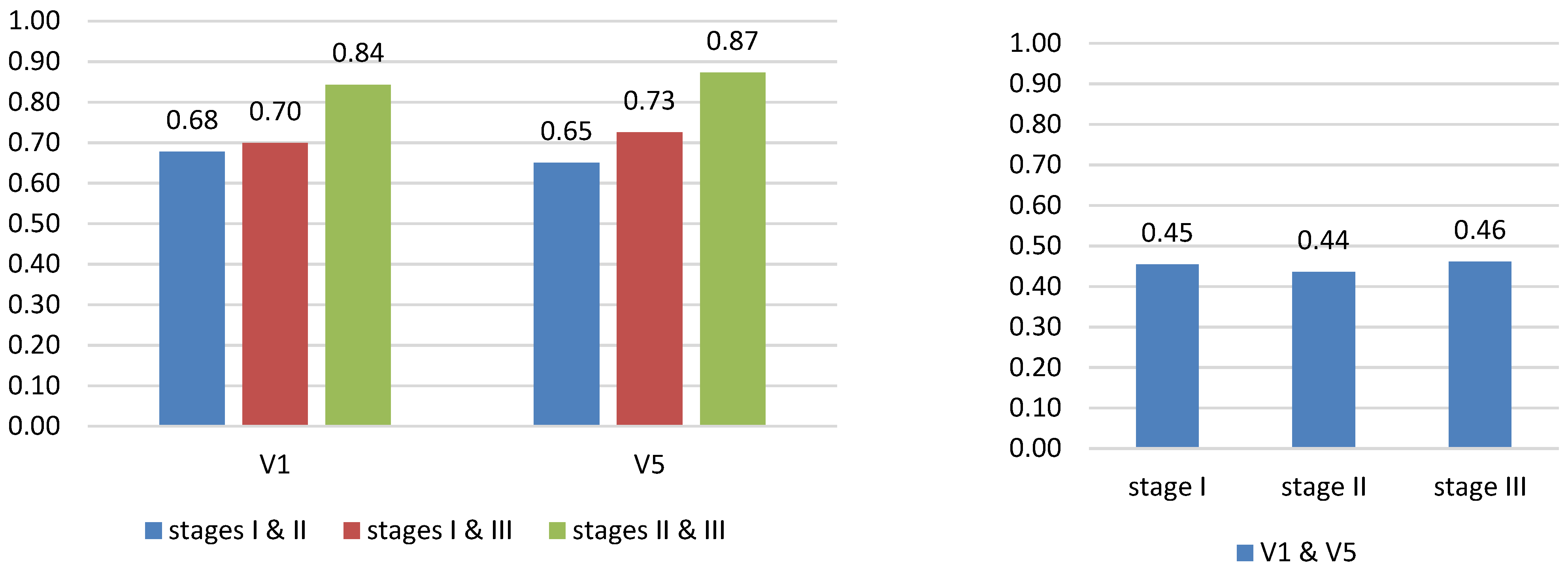

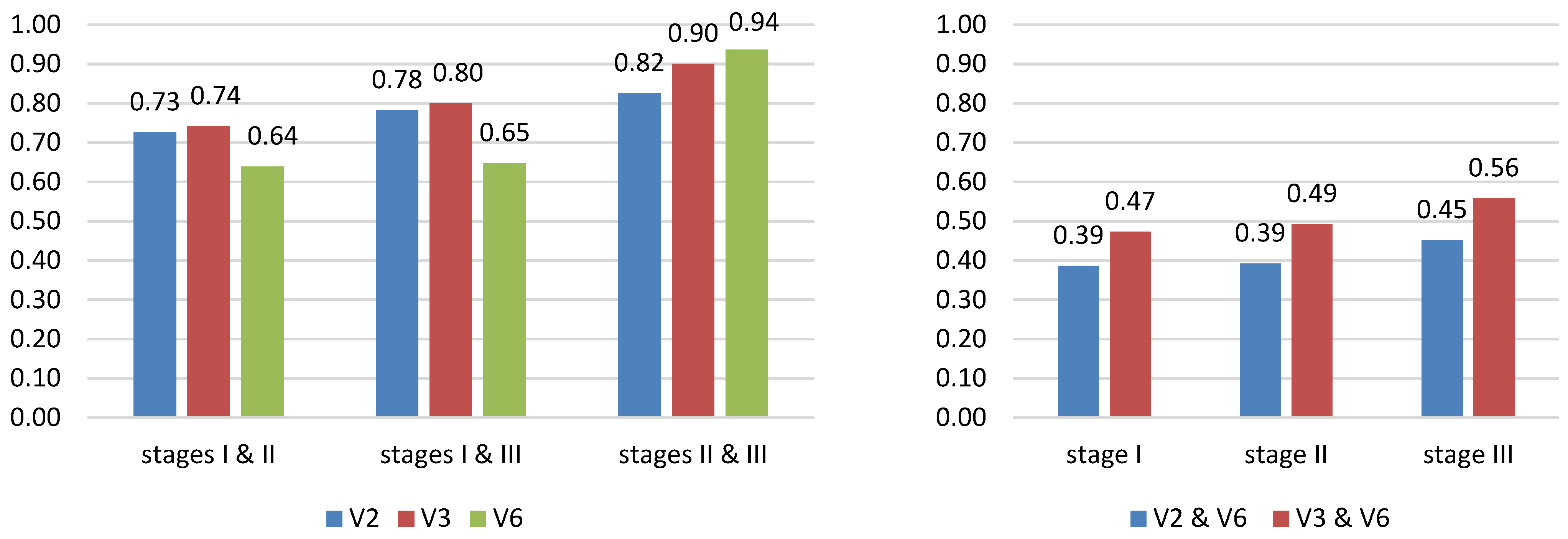

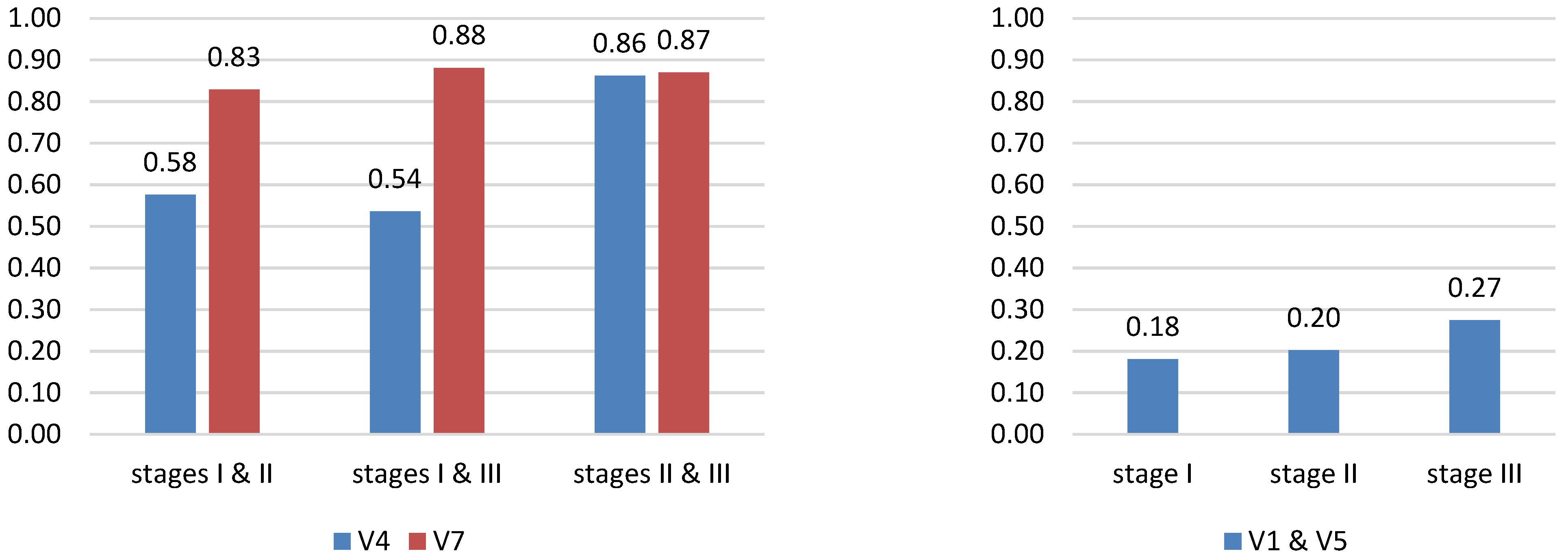

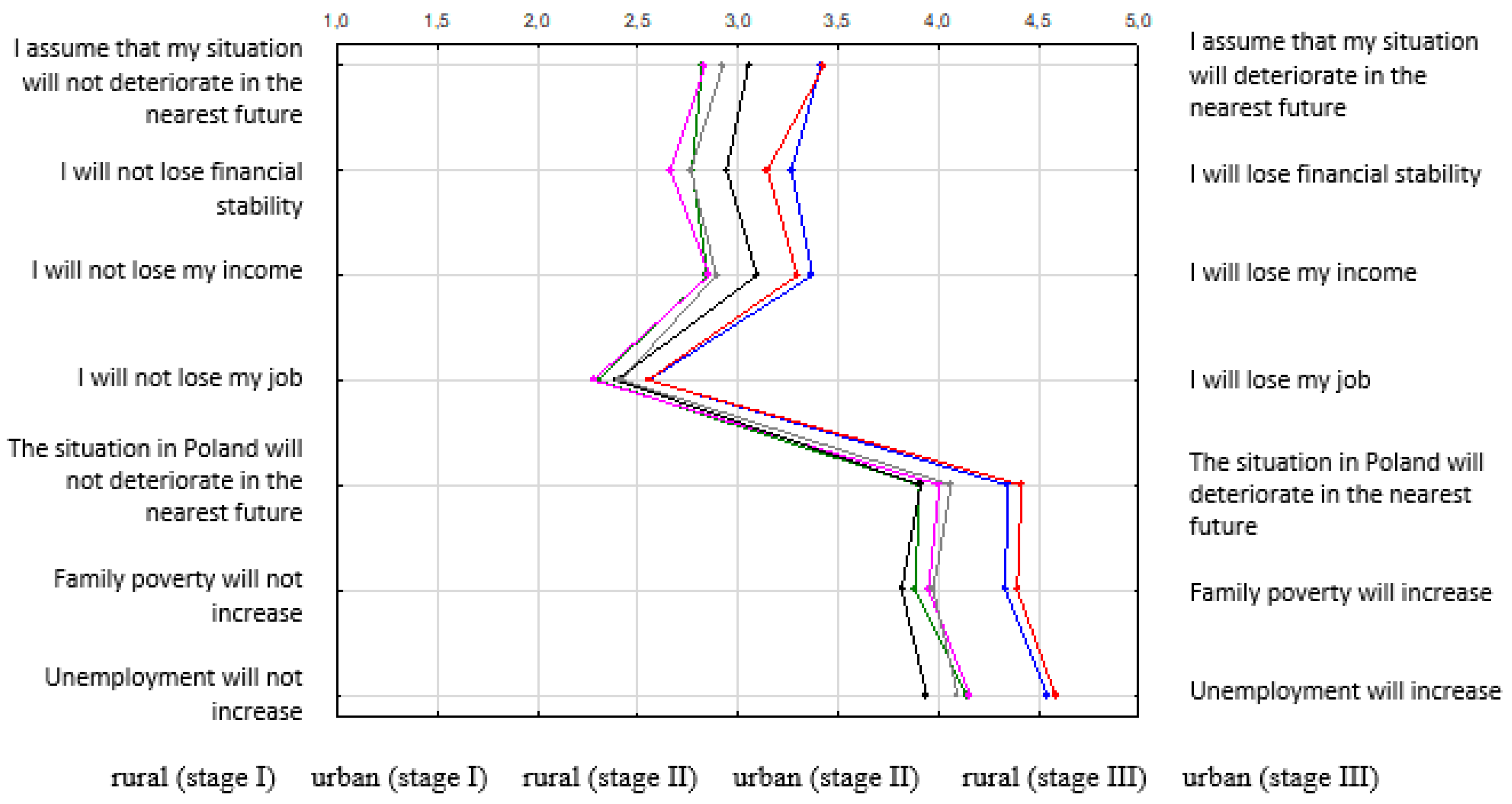

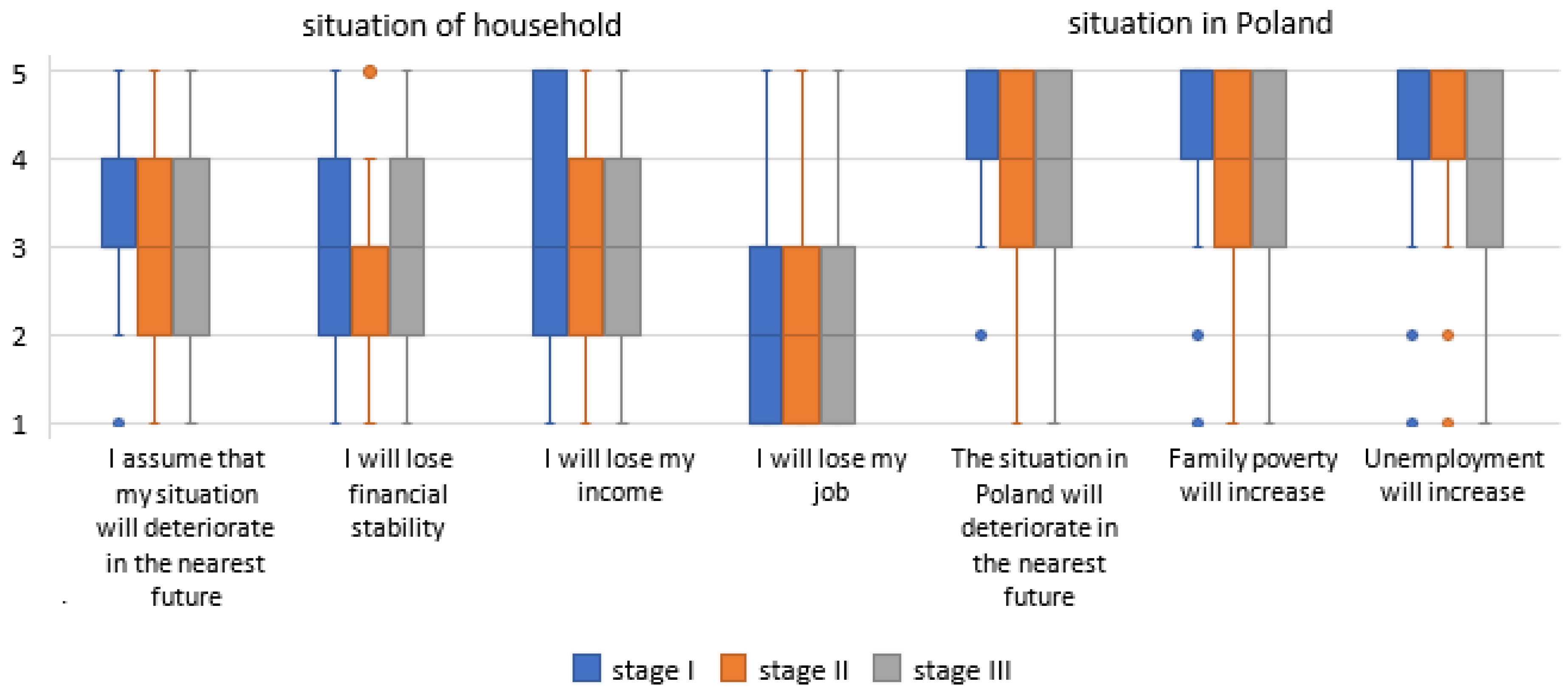

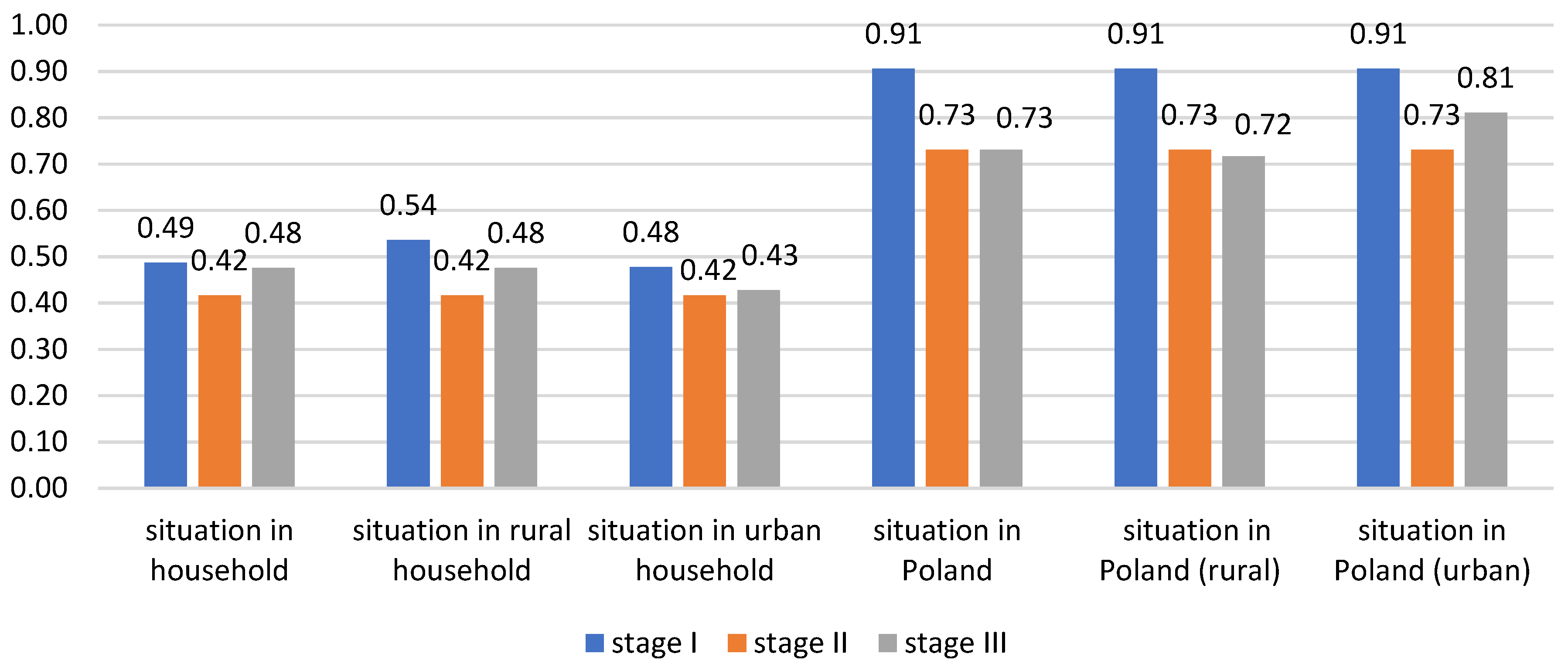

3.2. Subjective Assessment of the Level of Social Insecurity Concerning the Future Situation of One’s Household and the Situation in Poland

4. Discussion

5. Summary

6. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan, M.M.; Sadak, C. Exploring housing market and urban densification during COVID-19 in Turkey. J. Urban Manag. 2021, 10, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.R.; Lee, A.D.; Zou, D. COVID-19 and housing prices: Australian evidence with daily hedonic returns. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 43, 101960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denysov, O.; Litvin, N.; Lotariev, A.; Yegorova-Gudkova, T.; Akimova, L.; Akimov, O. Management of State Financial Policy in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ad Alta J. Interdiscip. Res. 2021, 11, 52–57. Available online: http://www.magnanimitas.cz/ADALTA/110220/papers/A_09.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Meyer, V.; Caporal, J. The Shifting Roles of Monetary and Fiscal Policy in Light of COVID-19; Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS): Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.csis.org/analysis/shifting-roles-monetary-and-fiscal-policy-light-covid-19 (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Dudek, M.; Śpiewak, R. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Sustainable Food Systems: Lessons Learned for Public Policies? The Case of Poland. Agriculture 2022, 12, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska-Solis, J.; Barska, A. Exploring the Preferences of Consumers’ Organic Products in Aspects of Sustainable Consumption: The Case of the Polish Consumer. Agriculture 2021, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śmiglak-Krajewska, M.; Wojciechowska-Solis, J. Consumer versus Organic Products in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Opportunities and Barriers to Market Development. Energies 2021, 14, 5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muça, E.; Pomianek, I.; Peneva, M. The Role of GI Products or Local Products in the Environment—Consumer Awareness and Preferences in Albania, Bulgaria and Poland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hromada, E.; Cermakova, K. Financial unavailability of housing in the Czech Republic and recommendations for its solution. Int. J. Econ. Sci. 2021, 10, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecrdlova, A. Comparison of the approach of the Czech National Bank and the European Central Bank to the effects of the global financial crisis. Int. J. Econ. Sci. 2021, 10, 18–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.L.; Fatimahwati Pehin Dato Musa, S. Agritourism resilience against COVID-19: Impacts and management strategies. Cogent Soc. 2021, 7, 1950290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Nørfelt, A.; Josiassen, A.; Assaf, A.G.; Tsionas, M.G. Understanding the COVID-19 tourist psyche: The Evolutionary Tourism Paradigm. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 103053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakibaei, S.; de Jong, G.C.; Alpkökin, P.; Rashidi, T.H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on travel behavior in Istanbul: A panel data analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 65, 102619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, R.; Yu, X.; Wang, W.; Ning, G.; Bi, Y. Spatial transmission of COVID-19 via public and private transportation in China. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 34, 101626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asmundson, G.J.G.; Taylor, S. Coronaphobia: Fear and the 2019-nCoV outbreak. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 70, 102196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chulasiri, P.; Ruwanpathirana, T.; Gunawardena, N.; Wickramasinghe, C.; Lokuketagoda, B. Perceptions of the current COVID situation and health, social and economic impact of the current scenario among a rural setting in Anuradhapura district. J. Postgrad. Inst. Med. 2020, 7, E123 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halamska, M. Rural crumbs of the pandemic: Communities and their institutions. Introduction to the thematic issue. Wieś Roln. 2020, 3, 12–16. Available online: https://kwartalnik.irwirpan.waw.pl/wir/article/view/750/680 (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Hall, M.C.; Prayag, G.; Fieger, P.; Dyason, D. Beyond panic buying: Consumption displacement and COVID-19. J. Serv. Manag. 2021, 32, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowski, S. Od paniki do negacji: Zmiana postaw wobec COVID-19 (From panic to denial: Changing attitudes towards COVID-19). Wieś Roln. 2020, 3, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowski, S.; Wyduba, W. Moja Sytuacja w Okresie Koronawirusa. Raport Końcowy (My Situation during the Coronavirus Period. Final Report); Instytut Rozwoju Wsi i Rolnictwa PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2020; Available online: http://admin2.irwirpan.waw.pl/dir_upload/site/files/IRWiR_PAN/Raport_Koncowy_IRWiR.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- McCarthy, J.U.S. Coronavirus Concerns Surge, Government Trust Slides. Gallup News: Politics 2020, Published Electronically March 16. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/295505/coronavirus-worries-surge.aspx (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Naeem, M. Do social media platforms develop consumer panic buying during the fear of COVID-19 pandemic. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolting, T. COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) in Germany: A Holistic Approach: A Communication-Psychological, Socio-Philosophical and Biomedical Analysis of the Pandemic. Release: 20 May 2020, Duesseldorf, Germany. Update: 1 November 2020, cf. p. 48. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/345136477_Covid-19_SARS-CoV-2_in_Germany_A_holistic_approach (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Kadeřábková, B.; Jašová, E. How the Czech government got the pandemic wrong. In Proceedings of the 15th Economics and Finance Conference, Prague, Czech Republic, 21–22 June 2021; pp. 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowski, S.; Łuczak, A. Social (in) security—The ambivalence of villagers’ perceptions during COVID-19. Soc. Policy Issues 2021, 54, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, F.H. Risk, Unicertainty and Profit; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, MA, USA; New York, NY, USA, 1921; Available online: https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/books/risk/riskuncertaintyprofit.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Beck, U. Społeczeństwo Ryzyka. W Drodze Do Innej Nowoczesności, 2nd ed.; Original Work: Risikogesellschaft, Published 2000; Cieśla, S., Translator; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar: Warszawa, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zalega, T. Konsumpcja w Gospodarstwach Domowych o Niepewnych Dochodach (Consumption in Households with Precarious Income); Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego: Warszawa, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kalinowski, S. Pewni niepewności (Confident in uncertainty). In Życie na Skraju—Marginesy Społeczne Wielkiego Miasta (Living on the Edge—The Social Margins of a Big City); Galor, Z., Goryńska-Bittner, B., Kalinowski, S., Eds.; Societas Pars Mundi: Bielefeld, Germany, 2014; pp. 387–404. Available online: http://www.spmpublishing.eu/?zycie-na-skraju-%E2%80%93-marginesy-spoleczne-wielkiego-miasta,8 (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Sowińska, A. Strategie zaradcze w sytuacjach utraty bezpieczeństwa socjalnego (Remedial strategies for coping with situation of social security depravation). In Bezpieczeństwo Socjalne (Social Security); Frąckiewicz, L., Ed.; Wydawnictwo AE im. Karola Adamieckiego: Katowice, Poland, 2003; pp. 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, G.; Anderson-Nathe, B. Uncertainty in the time of coronavirus. Child Youth Serv. 2020, 41, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coibion, O.; Gorodnichenko, Y.; Weber, M. Labor Markets during the COVID-19 Crisis: A Preliminary View; NBER Working Paper Series, No. 27017; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNapoli, T.P. Under Pressure: Local Government Revenue Challenges during the COVID-19 Pandemic; Office of the New York State Comptroller: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.osc.state.ny.us/files/local-government/publications/pdf/local-government-revenue-challenges-during-covid-19-pandemic.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Zwęglińska-Gałecka, D. Koronakryzys. Lokalne zróżnicowanie globalnej pandemii (The coronavirus crisis: Local responses to the global pandemic). Wieś Roln. 2020, 3, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, V.; Barrios, S.; Christl, M.; de Poli, S.; Tumino, A.; van der Wielen, W. The impact of COVID-19 on households’ income in the EU. J. Econ. Inequal. 2021, 19, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hromada, E.; Čermáková, K.; Krulický, T.; Machová, V.; Horák, J.; Mitwallyova, H. Labour Market and Housing Unavailability: Implications for Regions Affected by Coal Mining. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2021, 26, 404–414. [Google Scholar]

- Dudek, H. Households’ food insecurity in the V4 countries: Microeconometric analysis. Amfiteatru Econ. 2019, 21, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczak, A.; Kalinowski, S. Assessing the level of the material deprivation of European Union countries. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, M.; Doherty, B.; Pybus, K.J.; Pickett, K.E. How COVID-19 has exposed inequalities in the UK food system: The case of UK food and poverty [version 1; peer review: 3 approved, 2 approved with reservations]. Emerald Open Res. 2020, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dudek, H.; Szczesny, W. Multi-dimensional material deprivation in the Visegrád Group: Zero-inflated beta regression modelling. In Analysis of Socio-Economic Conditions: Insights from a Fuzzy Multi-Dimensional Approach; Betti, G., Lemmi, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, J.; Kelly, B.; Lockyer, B.; Bridges, S.; Cartwright, C.; Willan, K.; Shire, K.; Crossley, K.; Bryant, M.; Sheldon, T.A.; et al. Experiences of lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic: Descriptive findings from a survey of families in the Born in Bradford study [version 2; peer review: 2 approved]. Wellcome Open Res. 2021, 5, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, F.A.I.; Santos, M.E.; London, S. Multidimensional poverty and natural disasters in Argentina (1970–2010). J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowski, S. My Situation during the Coronavirus Pandemic; Unpublished source material in Polish; Institute of Rural and Agricultural Development of the PAS: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Poland [GUS]. Household Budget Survey in 2019; Statistics Poland, Social Surveys Department: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/living-conditions/living-conditions/household-budget-survey-in-2019,2,14.html (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Sobczyk, M. Statystyka Opisowa (Descriptive Statistic); Wydawnictwo C.H. Beck: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-T. Extensions of the TOPSIS for group decision-making under fuzzy environment. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2000, 114, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantaphyllou, E. Multi-Criteria Decision Making Methods: A Comparative Study; Applied Optimization; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; Volume 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F.; Tzeng, G.-H. Combining grey relation and TOPSIS concepts for selecting an expatriate host country. Math. Comput. Model. 2004, 40, 1473–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-H.; Yeh, C.-H. A new airline safety index. Transport. Res. B-Meth. 2004, 38, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska, E.; Wachowicz, T. Application of fuzzy TOPSIS to scoring the negotiation offers in ill-structured negotiation problems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 242, 920–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña-Soto, C.M.; Liern, V.; Pérez-Gladish, B. Normalization in TOPSIS-based approaches with data of different nature: Application to the ranking of mathematical videos. Ann. Oper. Res. 2021, 296, 541–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocki, F. Metody Taksonomiczne w Rozpoznawaniu Typów Ekonomicznych Rolnictwa i Obszarów Wiejskich (Taxonomic Methods in Recognizing Economic Types of Agriculture and Rural Areas); Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego: Poznań, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, S.; Rowlingson, K. The aims of social security. In Social Security in Britain; McKay, S., Rowlings, K., Eds.; Palgrave: London, UK, 1999; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, D.; Wills-Herrera, E. Introduction. In Subjective Well-Being and Security; Social Indicators Research Series; Webb, D., Wills-Herrera, E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2012; Volume 46, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StatSoft Polska. Statistica 13.3 Zestaw Plus Wersja 5.0.80 2021; StatSoft Polska: Kraków, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos Martin, B.A. FuzzyMCDM: Multi-Criteria Decision Making Methods for Fuzzy Data. R Package Version 1.1. 2016. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=FuzzyMCDM (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Łuczak, A.; Kalinowski, S. Fuzzy Clustering Methods to Identify the Epidemiological Situation and Its Changes in European Countries during COVID-19. Entropy 2022, 24, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, E.A.; Garfin, D.R.; Silver, R.C. Media’s role in broadcasting acute stress following the Boston Marathon bombings. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van den Bulck, J.; Custers, K. Television exposure is related to fear of avian flu, an Ecological Study across 23 member states of the European Union. Eur. J. Public Health 2009, 19, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Latour, B. Przedmioty Także Posiadają Sprawczość (Objects Too Have Agency). In Teoria Wiedzy o Przeszłości na tle Współczesnej Humanistyki. Antologia (Theory of Knowledge of the Past and the Contemporary Human and Social Sciences); Domańska, E., Ed.; Derra, A., Translator; Wydawnictwo Poznańskie: Poznań, Poland, 2010; pp. 525–560. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D. Objective happiness. In Well-Being: Foundations of Hedonic Psychology; Kahneman, D., Diener, E., Schwarz, N., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Van Praag, B.M.S.; Frijters, P. The measurement of welfare and well-being: The Leyden approach. In Well-Being: Foundations of Hedonic Psychology; Kahneman, D., Diener, E., Schwarz, N., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 413–433. [Google Scholar]

- Michoń, P. Ekonomia Szczęścia (The Economics of Happiness); Wydawnictwo Harasimowicz: Poznań, Poland, 2010; Available online: https://www.wbc.poznan.pl/dlibra/publication/242598/edition/202243/ (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Zaleśkiewicz, T. Psychologia Ekonomiczna (Economic Psychology); Gdańskie Wydawnictwo Psychologiczne: Gdańsk, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Strube, M.J.; Lott, C.L.; Lê-Xuân-Hy, G.M.; Oxenberg, J.; Deichmann, A.K. Self-evaluation of abilities: Accurate self-assessment versus biased self-enhancement. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koźmiński, A.K.; Zagórski, K. Społeczeństwo w czasach kryzysu i niepewności ekonomicznej. Założenia, pojęcia, hipotezy (Society in times of crisis and economic uncertainty: Assumptions, concepts, hypotheses). In Postawy Ekonomiczne w Czasach Niepewności. Ekonomiczna Wyobraźnia POLAKÓW 2012–2014 (Economic Attitudes in Times of Uncertainty. Economic Imagination of Poles 2012–2014); Zagórski, K., Koźmiński, A.K., Morawski, W., Piotrowska, K., Rae, G., Strumińska-Kutra, M., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar: Warszawa, Poland, 2015; pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, V.L. Rationality in Economics: Constructivist and Ecological Forms; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, R.; Weder di Mauro, B. (Eds.) Economics in the Time of COVID-19; CEPR Press: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://voxeu.org/article/economics-time-covid-19-new-ebook (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Djankov, S.; Panizza, U. Developing economies after COVID-19: An introduction. In COVID-19 in Developing Economies; Djankov, S., Panizza, U., Eds.; CEPR Press: London, UK, 2020; pp. 8–23. Available online: https://voxeu.org/content/covid-19-developing-economies (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Valensisi, G. COVID-19 and global poverty: Are LDCs being left behind? Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2020, 32, 1535–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runciman, W.G. Problems of research on relative deprivation. Arch. Eur. Sociol. 1961, 2, 315–323. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23987944 (accessed on 6 May 2021). [CrossRef]

- Gurney, J.N.; Tierney, K.J. Relative deprivation and social movements: A critical look at twenty years of theory and research. Sociol. Q. 1982, 23, 33–47. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/410635 (accessed on 6 May 2021). [CrossRef]

- Boudon, R. Effets Pervers et Ordre Social; Quadrige/Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.E. The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Grasso, M.T.; Yoxon, B.; Karampampas, S.; Temple, L. Relative deprivation and inequalities in social and political activism. Acta Polit. 2019, 54, 398–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Degree of Similarity | Very Low Similarity | Low Similarity | Average Similarity | High Similarity | Very High Similarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0; 0.20) | [0.20; 0.40) | [0.40; 0.60) | [0.60; 0.80) | [0.80; 1.00) |

| Linguistic Variable Level | Definitely Not | No | Maybe | Yes | Definitely Yes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five-point scale | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Triangular fuzzy numbers (a, b, c) | (0, 0, 20) | (20, 30, 40) | (40, 50, 60) | (60, 70, 80) | (80, 100, 100) |

| Level | Very Low | Low | Medium | High | Very High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0.00; 0.20) | [0.20; 0.40) | [0.40; 0.60) | [0.60; 0.80) | [0.80; 1.00) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kalinowski, S.; Łuczak, A.; Koziolek, A. The Social Dimension of Security: The Dichotomy of Respondents’ Perceptions during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1363. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031363

Kalinowski S, Łuczak A, Koziolek A. The Social Dimension of Security: The Dichotomy of Respondents’ Perceptions during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2022; 14(3):1363. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031363

Chicago/Turabian StyleKalinowski, Sławomir, Aleksandra Łuczak, and Adam Koziolek. 2022. "The Social Dimension of Security: The Dichotomy of Respondents’ Perceptions during the COVID-19 Pandemic" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1363. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031363

APA StyleKalinowski, S., Łuczak, A., & Koziolek, A. (2022). The Social Dimension of Security: The Dichotomy of Respondents’ Perceptions during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 14(3), 1363. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031363