Small Rural Enterprises and Innovative Business Models: A Case Study of the Turin Area

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- design sustainable value incorporating value forms in terms of economic, social, and environmental benefits;

- create a system of sustainable value flows among multiple actors, where the primary stakeholders are the natural environment and society;

- suggest a new purpose, design, and governance that will generate a value network;

- consider the interests of every stakeholder and their responsibilities for mutual value creation;

- internalizing the externalities through the Product Service System (“a market proposition that extends the traditional functionality of a product by incorporating additional services” [13]) that enables innovation towards sustainable business models.

2. Materials and Methods

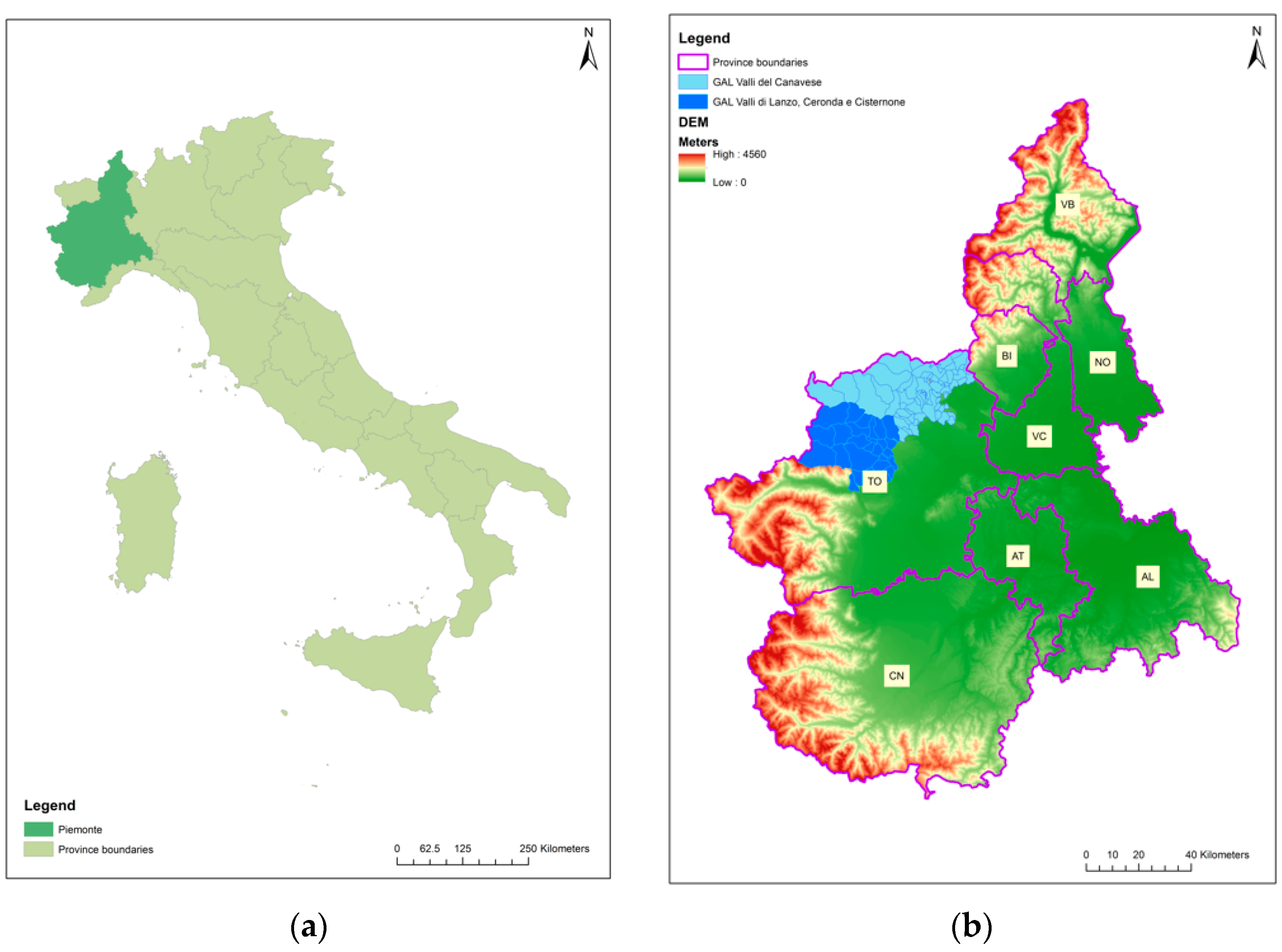

2.1. Desk Analysis

2.2. Living Lab Approach

- Confederation of business owners “Camera di Commercio”;

- Confederation of artisans “CNA—Confederazione nazionale dell’artigianato e della piccola e media impresa”;

- Trade association of farmers “Coldiretti Torino”;

- Metropolitan city of Turin;

- Start-up of the University of Turin “Incubatore 2i3T”;

- The University of Pisa.

2.3. Modelling Phase

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giesen, E.; Berman, S.J.; Bell, R.; Blitz, A. Three ways to successfully innovate your business model. Strateg. Leadersh. 2007, 35, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girotra, K.; Netessine, S. OM Forum—Business Model Innovation for Sustainability. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2013, 15, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation. Long Range Plann. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizos, V.; Behrens, A.; van der Gaast, W.; Hofman, E.; Ioannou, A.; Kafyeke, T.; Flamos, A.; Rinaldi, R.; Papadelis, S.; Hirschnitz-Garbers, M.; et al. Implementation of Circular Economy Business Models by Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs): Barriers and Enablers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moriggi, A. Exploring enabling resources for place-based social entrepreneurship: A participatory study of Green Care practices in Finland. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 15, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mathe, S. Integrating participatory approaches into social life cycle assessment: The SLCA participatory approach. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2014, 19, 1506–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, C.L.; Broman, G.; Robèrt, K.-H.; Basile, G.; Trygg, L. An approach to business model innovation and design for strategic sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkdahl, J.; Holmén, M. Editorial: Business model innovation—The challenges ahead. Int. J. Prod. Dev. 2013, 18, 213–225. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Evans, S.; Vladimirova, D.; Rana, P. Value uncaptured perspective for sustainable business model innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 1794–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nosratabadi, S.; Mosavi, A.; Shamshirband, S.; Kazimieras Zavadskas, E.; Rakotonirainy, A.; Chau, K.W. Sustainable Business Models: A Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evans, S.; Vladimirova, D.; Holgado, M.; Van Fossen, K.; Yang, M.; Silva, E.A.; Barlow, C.Y. Business Model Innovation for Sustainability: Towards a Unified Perspective for Creation of Sustainable Business Models. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2017, 26, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Freund, F.L.; Hansen, E.G. Business cases for sustainability: The role of business model innovation for corporate sustainability. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 6, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annarelli, A.; Battistella, C.; Nonino, F. Product service system: A conceptual framework from a systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 139, 1011–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Bessant, J.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Overy, P.; Denyer, D. Innovating for Sustainability: A Systematic Review of the Body of Knowledge; Network for Business Sustainability: Ontario, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, A.; Asif, F.M.A.; Krajnik, P.; Nicolescu, C.M. Resource Conservative Manufacturing: An essential change in business and technology paradigm for sustainable manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 57, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Leminen, S.; Westerlund, M. A systematic review of living lab literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 976–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards-Schachter, M.E.; Matti, C.E.; Alcántara, E. Fostering Quality of Life through Social Innovation: A Living Lab Methodology Study Case. Rev. Policy Res. 2012, 29, 672–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leminen, S.; Westerlund, M.; Nyström, A.-G. Living Labs as Open-Innovation Networks. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2012, 2, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergvall-Kåreborn, B.; Holst, M.; Ståhlbröst, A. Concept Design with a Living Lab Approach. In Proceedings of the 2009 42nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Herselman, M.; Marais, M.; Pitse-Boshomane, M. Applying living lab methodology to enhance skills in innovation. In Proceedings of the eSkills Summit, Cape Town, South Africa, 26–28 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- U4IoT Living Lab Methodology Handbook. Available online: https://www.northwalescollaborative.wales/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Living-lab-methodology-handbook_r.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- United Nations. THE 17 GOALS. Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Wilson, C.E. Brainstorming pitfalls and best practices. Interactions 2006, 13, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, A.E.; Bolt, J.S.; Jat, H.S.; Jat, M.L.; Kumar, M.; Agarwal, T.; Blok, V. Business models of SMEs as a mechanism for scaling climate smart technologies: The case of Punjab, India. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 1109–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partalidou, M.; Paltaki, A.; Lazaridou, D.; Vieri, M.; Lombardo, S.; Michailidis, A. Business model canvas analysis on Greek farms implementing Precision Agriculture. Agric. Econ. Rev. 2021, 19, 28–45. [Google Scholar]

- Sivertsson, O.; Tell, J. Barriers to Business Model Innovation in Swedish Agriculture. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1957–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-470-87641-1. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4129-6099-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pickton, D.W.; Wright, S. What’s swot in strategic analysis? Strateg. Chang. 1998, 7, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomares-Aguirre, I.; Barnett, M.; Layrisse, F.; Husted, B.W. Built to scale? How sustainable business models can better serve the base of the pyramid. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 4506–4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldmann, E.; Huulgaard, R.D. Barriers to circular business model innovation: A multiple-case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Iacovo, F.; Fumagalli, S.; Sabbadini, M.; Venturelli, S. La co-produzione innovativa in agricoltura sociale: Sentieri, organizzazione e collaborazioni nelle nuove reti locali. In Proceedings of the VII Edizione del Colloquio Scientifico Annuale Sull’impresa Sociale, IrisNetwork, Torino, Italy, 7–8 June 2013; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

| Methodology Steps | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Desk analysis | Increasing knowledge and understanding of the territory involved in the study |

| Living Lab approach | Process of collaborative participation to define the shared objectives between political and research institutions and representatives of the different categories of entrepreneurs of the territory |

| Modeling approach | Planning and co-creation of new sustainable business models through specific workshops to stimulate the discussion between small entrepreneurs’ representatives of the study area |

| Leather Accessories from Local Bovines | Eco-Friendly Packaging for Local Products | Worth Agreement for Stakeholders | Civil Food through the Work of Marginalized People | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partners | Local bovine farmers, tanneries and leather artisans for production. Local shops and touristic services for distribution. | Food producers and restaurants of the territory, Polytechnic University of Turin, packaging industries and trade association. | Small enterprises, touristic facilities and local institutions (as municipalities and Metropolitan City of Turin, Local Action Groups etc.). | Food production, transformation and distribution enterprises, Local Health Units, associations for marginalized people. |

| Activities | Produce high quality local bovine leather accessories from butchery waste through eco-friendly tanning procedures. | Creation of a new eco-friendly packaging dedicated to local products that describes the territory with attention to food safety and design. | Coordinated promotion of the territory trough the activities and products of the members of the Worth Agreement. | Networking between the firms and the social and health services of the territory to promote a constant work inclusion. |

| Resources | Experience and instruments given by the partners. A dedicated website for the promotion. | Technological skills for the development and equipment for the production given by the University and industries. | Entrepreneurs and administrators will in collaborating for the objective demonstration of their commitment in the Worth Agreement. | Communication channels for firms and services to match the social need of the territory and the availability in social inclusion. |

| Value Proposition | High ethical background (with respect to animal welfare, traceability, traditions, and low carbon footprint). | Avoiding the production of non-recyclable waste while communicating the high quality of the products and the strong bond with the territory. | Commitment in respecting shared rules and values for conducting their entrepreneurial activities, preserving the territory in its entirety. | Social inclusion for marginalized people that gives ethical added value to local food products that, in this way, can be considered Civil Food. |

| Customer Relationship | Communication of the values behind the products. Possibility to customise the accessory because of its handcrafted nature. | Direct communication of the eco-friendly aim, quality and bond with the territory of the food product that they are buying. | Possibility for customer to be sure in investing in activities and products that take with them preservation values. | Coherent communication of the social and ethical values behind the product with explanation of the importance of social inclusion. |

| Channels | Promote and valorise designed products both on internet and in the touristic services (e.g., accommodation and restaurants). | Local food shops and street markets managed by trade associations where the packaging could be used for specific local products. | Institutional promotion on their communication channels to reach consumers of the territory and tourists. | Promotion and distribution of the Civil Food in local food shops, street markets and in the restaurants of the territory. |

| Customer Segments | People sensitive to environmental issues and that want original and characteristic accessories. | People of the territory and tourists that are interested in local products and also give value to waste reduction. | Locals and tourists looking for an experience that connects the holiday with preservation of nature and traditions of the place. | Local consumers that give importance to social issues so are willing to pay more the goods for their Civil value. |

| Costs | Changing of the tanning processes to more eco-friendly ones, creation and maintenance of the website. | Investment on technology and equipment for the development and the production in large scale of the new packaging. | Creation of a shared certification system to guarantee to consumers the respect of the shared rules and values. | Need of financing marginalized people and reorganizing the work to include in an easier way this category of workers. |

| Revenues | Higher price of the leather for farmers and higher price for accessories because of the ethical values behind it. | Less production of non-recyclable waste, reduction of the cost of advertising the territory because the packaging communicates itself. | Better promotion of the activities of the members of the Worth Agreement with less individual expense in advertising. | Possibility to access to financing projects for social activities and to obtain a higher price for the Civil Food products. |

| Innovative Business Idea | Strengths and Opportunities | Weaknesses and Threats |

|---|---|---|

| Leather accessories from local bovines | Possibility of gaining a higher price for the leather and creating a territorial circular economy with local artisans and farmers that can preserve traditions and create new job opportunities. More attention to the environmental aspects of the treatment of leather because everything is done locally. | Need of the involvement of a good number of farms to have an adequate supply of leather. Consideration of the methods of manufacturing because some leather tanning methods have a high impact on the environment and this prejudice can give a negative image to the project if there is not clear communication to consumers. |

| Eco-friendly Packaging for local products | The presence on the territory of actors with the skills to develop the technology (Polytechnic University of Turin) and to organize the supply chain (the trade association of farmers) taking advantage of the awareness of environmental issues. The packaging itself could become a communication tool for the initiatives of the territory oriented to sustainability and territorial integration. | Creation of a network between the interested farmers and clear definition of the products that have to be packed to help in the development of adequate packaging that have to guarantee the safety of the food. The probable high costs. The stiffness of the laws in the field may be an obstacle in the testing of new materials to pack the food. |

| Worth Agreement for stakeholders | The presence of lots of local products and services that could be potentially involved in the Agreement and the near metropolitan city of Turin to promote it. The fact that the Worth Agreement is a starting point for constant collaboration between different local stakeholders that could help the development of further projects on ecosystem services. | A mistrust in some stakeholders in this kind of large collaboration agreement could increase bureaucracy. The difficulty in the promotion and communication of the values at the foundation of the project and the fact that some consumers are still not so sensitive about the positive effects of correct management of the services and supply chains in the territory and the costs that this implies. |

| Civil Food through the work of marginalized people | Possibility to grow new entrepreneurial perspectives through social inclusion that can give both a reduction of costs for the health and social services and a diversification alternative for farms. The ethical value that the products gain when obtained with the work inclusion of disadvantaged people enables the possibility to reach a new market niche and to promote the territory as an inclusive one. | Problems in creating a stable network with the social and health services that could guarantee an adequate selection and follow-up of the disadvantaged people involved. Difficulties in translating the ethical value into a commensurate monetary value and conveying it to the consumers to make them understand the reasons for the higher price of Civil Food products. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galardi, M.; Moruzzo, R.; Riccioli, F.; Granai, G.; Di Iacovo, F. Small Rural Enterprises and Innovative Business Models: A Case Study of the Turin Area. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031265

Galardi M, Moruzzo R, Riccioli F, Granai G, Di Iacovo F. Small Rural Enterprises and Innovative Business Models: A Case Study of the Turin Area. Sustainability. 2022; 14(3):1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031265

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalardi, Morgana, Roberta Moruzzo, Francesco Riccioli, Giulia Granai, and Francesco Di Iacovo. 2022. "Small Rural Enterprises and Innovative Business Models: A Case Study of the Turin Area" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031265

APA StyleGalardi, M., Moruzzo, R., Riccioli, F., Granai, G., & Di Iacovo, F. (2022). Small Rural Enterprises and Innovative Business Models: A Case Study of the Turin Area. Sustainability, 14(3), 1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031265