Abstract

Throughout the world, including in developed countries, the COVID-19 crisis has revealed and accentuated food insecurity. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations clearly defines food security as a situation of not only availability and accessibility but also social acceptability (i.e., adequacy and sustainability). In developed countries, food security remains non-achieved at all. Notably, the so-called “little deprivation” leads the working poor to rely on food aid. We argue that even doing so, they remain food insecure: food aid is socially unacceptable because, despite their work, they are kept away from classical food access paths. In this article, we present the specificities of food aid in France and state some of its limits, namely those associated with the supply chain of donated foodstuffs. We propose a monographic study relying on a mix of firsthand material (six years of fieldwork from students with associations) and secondhand material (analysis of specialized, legal, and activity reports). We describe inspiring initiatives from three French associations and mobilize the recently published analysis of dignity construction in food aid in the United States of America to argue that dignity in food aid logistics is also a knowledge management and digital matter. Indeed, the initiatives of the three considered associations show concretely how knowledge management and digital systems can enhance dignity in food aid logistics.

1. Introduction

While 607 million people were undernourished in 2014, the global pandemic exacerbated world hunger up to 811 million in 2020 [1]. Yet, the right to food is recognized by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) of the United Nations as a fundamental right because it is crucial to the enjoyment of all the rights, including the right to health, to life, to access water, to adequate housing and education [2]. Moreover, according to the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, achieving food security is the second sustainable development goal, just after ending poverty [1]. For the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, food security is a situation occurring when “all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” [3]. Such a definition is recognized by the FAO as evolving to emphasize the centrality of sustainability.

Food insecurity issues are not only limited to developing countries. They concern, in different forms, acuteness, and issues, industrialized countries as well. They began to be considered in public policies in the early 1980s when, following the economic crisis, the President of the United States of America, Ronald Reagan, convened a working group on hunger in the USA. This led to the famous research by Radimer, who conducted a very large survey based on a questionnaire, which is still the reference in the field of food insecurity [4]. In line with the definition of food security in this work and following what we observe on the field, we argue that the social acceptability of food aid is crucial to ensure a dignified and consequently more sustainable food security for all.

Recent studies show how digital systems, when adequately used, can enhance some dignity concerns. For example, the level of disability parking misuse in New Zealand has been addressed through a digital initiative: citizens can report in an app disability parking unavailability and misuse, leading to drastically reducing such a level [1]. Sanchez-Segura et al. point that digitalization may help to ensure dignity, but researchers, practitioners, and citizens must be aware that there might be a digital transformation problem [5]. For Bay and Atherton, this occurs notably when vulnerable populations data are processed unethically and without social justice [6], or when the digital era turns initiatives such as knowledge management into an a priori sustainable solution, whose performance should be measured through metrics as pointed by Tosic and Zivkovic [7].

We argue in this paper that the issue of dignity in food aid may be regarded through the lens of the contribution of digital systems to knowledge management and supply chain performance. Many important subjects may be concerned. For example, as non-profit organizations engaged in food aid logistics rely massively on volunteers, the problem of knowledge retention adds to traditional logistic questions. However, as for Chapman and Corso, knowledge management continues to be seen as a costly and nontrivial process [8], the question of knowledge retention in food aid logistics remains unanswered.

The importance of knowledge management in food aid logistics may be perceived as certainly not straightforward. Additionally, even if social acceptability and dignity are considered crucial issues by food aid actors, the logistical and material constraints of foodstuffs distribution leads to situations where these aspects are sometimes sacrificed. In this article, we propose a paradigm switch by discussing how a digital system could enhance dignity in food aid logistics through knowledge management initiatives and allow non-profit organizations to achieve more socially acceptable, dignified, and sustainable food aid logistics. This is illustrated through the organization of food aid in France and highlighted by three inspiring initiatives. A monographic study is proposed relying on six years of fieldwork from students with associations, on the analysis of specialized and legal material, as well as on activities reports from associations.

In the second section of this article, we present related works: (i) the principles of food aid logistics in France, (ii) past research on knowledge management in food aid logistics, and (iii) the concept of dignity. In the third section, we present three initiatives in France showing how digital faces dignity through knowledge management in food aid logistics: (i) the initiative of the charity ReVivre and its AlimHotel decision support system, developed to improve the food situation of people housed in hotels, (ii) the forthcoming Geographic Information System (GIS) developed by the French Federation of Food Banks to solve the problem of the so-called “white zones”, i.e., areas of the territory that are not covered by a food aid network, and (iii) the initiative of the charity HopHopFood that developed a smartphone application aimed to fight against food waste of shops to the benefit of disadvantaged populations. In the fourth and fifth sections of this article, we propose a discussion and expose conclusions on the limitations of this research. The aim of this article is to share knowledge and experiences with the hope of raising the interest of academics on this important issue and the awareness of the idea that dignity in food aid logistics is also a knowledge management and digital matter.

2. Related Works

Understanding the issues to which the three initiatives answer requires knowledge and understanding of the complex organization of the food aid in France and its limits. We start this section by introducing the landscape of food aid in France, especially from the lens of supply chain constraints and limits. Second, we present works bridging knowledge management and food aid logistics. Third, we explain the concept of dignity regarding notably its relational, individual, and institutional dimensions.

2.1. Food Aid Logistics in France

In France, food insecurity is the subject of so-called “fight against food deprivation” public policies, which are based on the food aid sector and support it financially. This sector relies mainly on charity and operates through food aid associations. It is difficult to describe the organization of food aid in France exhaustively. In what follows, we underline certain striking characteristics that lead us to raise some limits in terms of dignity for beneficiaries.

The complexity of the organization of food aid in France can be described when discovering the architecture and the multiplicity of involved actors (public, private, and associations), the sources of funding, the modes of food supply as well as logistics and distribution methods. Such an organization is very dynamic because the associations constantly deploy innovative solutions seeking simultaneously the needs of the beneficiaries and the context, which are both constantly changing. As recently pointed by Darmon et al. and Cavaillet et al., the COVID-19 outbreak has emphasized the involvement of associations but has also strengthened the limits of the current food aid organization [9,10].

Almost all food aid in France is integrated into a global organization, which relies on three kinds of interdependent actors playing complementary roles listed by Bazin and Bocquet [11]:

- Public actors (French State, European Union, local governments such as regions and municipalities, etc.) regulate the mechanisms through public policies and allocate funding related to food and health.

- Private actors (companies, corporate foundations, individuals, etc.) intervene through donations such as financial donations, in-kind donations, sponsorship, and volunteering.

- Food aid associations finally manage almost all of the field questions (social support to recipients, stock management, logistics, distribution, etc.). They are the foundation upon which the whole edifice of food aid is based.

The latest information report concerning the financing of food aid in France, produced by Bazin and Bocquet, on behalf of the French Senate Finance Committee, estimated the amount of food aid in France to EUR 1.5 billion [11]. According to them, this amount is divided between:

- 36% from private resources (in-kind and cash donations from individuals, companies, farmers, foundations, sponsorship).

- 33% corresponding to the valuation of volunteering (200,000 volunteers).

- 31% from Public Funds (Fund for European Aid to the Most Deprived—FEAD, budgetary expenditure of the State and local authorities, tax expenditure via deductions linked to donations).

We observe that the number of volunteers is extremely important and is growing: another report from 2009 estimated it at 120,000 [12]. Such a number shows the strong presence of associations as the linchpin of food aid in France. Additionally, we have to note that financial aid remains marginal; as a matter of fact, in-kind contributions are predominant. Foodstuffs are mostly used to constitute parcels to be distributed, as supplies for social groceries or to prepare ready-to-eat meals. Some original but more marginal systems of distribution exist, such as cooking workshops, collective gardens, and cooperative grocery stores. These initiatives, often local, place more emphasis on the importance of sharing and socialization rather than on recurrent food aid.

Food aid in France has long been associated with the fight against waste and has been reinforced by the national strategy to fight against food waste through the Garot law promulgated in 2016 [13] and the EGalim law promulgated in 2018 [14]. These laws instituted the obligation for food companies such as supermarkets, manufacturers, collective catering, etc., to set up partnerships with food aid associations to give away unsold foodstuffs free of charge. This obligation is offset by a tax benefit corresponding to 60% of the value of the donation (up to 5 per thousand of turnover).

Despite the pragmatic nature of this public policy and beyond its perceived positive impact by associations—it generated deposits of food on a daily basis—it still establishes unequal access to food, as if the surpluses induced by the food system could be nobly used by being distributed to the most deprived. The issue of food aid is then presented as a way to engage in a kind of circular economy. After a few years of euphoria, which followed the implementation of the Garot law, we are observing within associations a scarcity of foodstuffs and especially a significant drop in their quality (particularly the use-by date of donated products). Food waste and food aid deposits being interrelated, the desired decline in the former (and the actions engaged by economic actors for that) leads the latter to be in difficulty [10].

Such an interrelation between food waste and food aid deposits raises an important question of dignity. Beyond this question, it forces the associations to manage pushed flows (from the sources of foodstuff) instead of pulled flows (by the beneficiaries’ needs). As defined by Pyke and Cohen, pushed flows correspond to the situation where upstream (supplies or manufacturing) generate flows on a forecast basis and “push” them towards the customer. Storage is then predominant, and overstocks, as well as disruptions, are unavoidable. Conversely, pulled flows correspond to the situation where the types of products and volumes are determined on the basis of information on customer present needs and along the supply chain, starting from market demand to produce only what is stated likely to be sold [15]. As the food aid supply chain in the French food aid sector relies mostly on foodstuff donations, it is constrained to manage pushed flows from sources of supply to associations and then to beneficiaries. On the field, such an organization for the distribution of foodstuffs leads to a real logistical brainteaser.

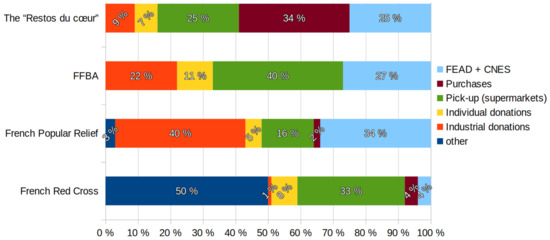

We observe, in 2019, a preponderance in foodstuff volumes of the Fund for European Aid to the Most Deprived (FEAD) and surpluses of supermarkets. Figure 1 shows such a distribution of the tonnages distributed for four principal associations in France according to foodstuffs origins [16].

Figure 1.

Distribution of foodstuffs according to their origin for the four historical associations in France (data aggregated from [16]). FEAD—Fund for European Aid to the Most Deprived; CNES—Crédit National des Épiceries Solidaires (French National Solidarity Grocery Credit); FFBA—Fédération Française des Banques Alimentaires (French Federation of Food Banks).

The first major source of foodstuffs for associations comes from the budget allocated by the European FEAD and the CNES (Crédit National des Épiceries Solidaires, French National Solidarity Grocery Credit) on a multi-year basis (light blue in Figure 1). FEAD Foodstuffs also constitutes a part of the “from other associations” volumes (dark blue in Figure 1).

In France, FranceAgrimer is the public body responsible for the budget execution on behalf of the European Union and the French state. Jointly with associations, FranceAgrimer establishes the list of foodstuffs for public tenders and is responsible for the execution of these tenders (27 products in the latest 2014–2020 program). On the demand side, FranceAgrimer works with the four French network associations listed in Figure 1 (designated by the French state) who report their needs relying on this list of products. The tenders concern the products and their delivery to the warehouses of these four associations: 17,000 deliveries to 389 logistics sites in 2019 [16]. Then, the network head associations are responsible for distributing these products among all their local partners (local branches, other associations, central social activities fund, etc.). Due to evident logistical constraints posed by this push-based supply organization and despite the efforts made by food aid organizations to contribute to a better assortment of healthy and nutritious products, the foodstuffs are often long-lasting products, especially ready meals, canned goods that do not match the dietary needs and preferences of the beneficiaries. The prices of FEAD products are said to be up to 50% cheaper than those found on the traditional market.

The second major source of foodstuffs for associations results from donations from economic players, namely the pick-up of unsold products from supermarkets and industrial donations (green and red in Figure 1, respectively). Since the Garot law notably, these constitute an important deposit of products that complement the offer of associations in fresh products (missing in foodstuffs from the FEAD and CNES). As an example, an average of five tons of food enters and leaves a Food Bank from the FFBA (French Federation of Food Banks) every day. The food is checked, sorted, recorded, and stored in a cold room for perishable or refrigerated food, in racks for dry products. Then, the picking is set up for the partner associations. Barely 2–3 h pass between the pick-up and the preparation of the pallets for the associations and 5–6 h before these products are made available to the associations [17]. These local and smaller associations or antennas then ensure the last-mile logistics.

These pushes from supermarkets to associations, unlike the ones acquired through the FEAD, are unpredictable in terms of volume, composition, or quality. As the reader can guess, associations do not know what they have for distribution before sorting operations. It is not possible to take into account the needs of associations and their beneficiaries. Supplies are fluctuating and of variable quality (more or less fresh products, more or less close use-by dates, etc.). Additionally, the quantities per collection point tend to be reduced in a food waste reduction trend, as discussed above considering the interrelation between food waste and food aid deposits. Associations often tend then to increase the number of collection points, consequently increasing their logistics costs.

In the description just given, several limitations of the food aid system in France emerge. We note that they might have an impact on the efficiency of the overall logistic organization. This question of performance is crucial for food aid associations, which are frugal organizations with the challenge of not wasting their resources. Each euro should contribute as much as possible to the improvement of food security for beneficiaries. However, the logistic costs represent a very important part of the operating costs for these organizations. Indeed, the products and labor are essentially free, coming from donations and through the investment of volunteers. Some recent trends point out the interest of knowledge management for the improvement of logistics and particularly of food logistics [18]. This raises then the question of a potential contribution that knowledge management could have for food aid logistics.

2.2. Knowledge Management in Food Aid Logistics

Within organizations, much information is generated and processed, with a need to flow throughout production processes. Information can be transmitted by speaking, writing, or acting and through the information system. It is recognized that knowledge is more than information. Information is data organized into meaningful patterns. Information is transformed into knowledge with the active intervention of individuals when they read, understand, interpret, and apply information to a specific work function. For Lee and Yang, knowledge becomes visible when experienced individuals put into practice lessons learned over time [19]. For Nonaka and Takushi, such knowledge can be tacit or explicit [20] and, as pointed out by Arduin et al. [21], this means that knowledge can either be:

- Tacit, i.e., it remains in individuals’ brains, it cannot always be made explicit, and it involves an individual interpretation.

- Made explicit, i.e., it has been made explicit by someone within a certain context; it is socially constructed and can be supported by digital systems.

Peterson argues that of the two types of knowledge, tacit knowledge may well be more valuable because of its uniqueness to an organization. Yet, it is also more difficult to capture, store, and transfer [22]. For Lee and Yang, knowledge management can then be defined as the deliberately designed organizational processes that govern the creation, dissemination, growth, and leveraging of knowledge to fulfill organizational objectives [19].

Consequently, knowledge sharing cannot be reduced to the transmission of information through digital technology [23]. Knowledge can be made explicit by someone in a certain context: it is then handled well by digital technology [22], but it can also remain tacit, i.e., interpreted by someone in a certain context. For authors such as Ives et al. [24], individuals should have not only the ability but also the motivation to share knowledge and particularly tacit knowledge. Socialization is then as critical as digital technology to implement knowledge management within organizations: made explicit knowledge might be shared via digital technology and tacit knowledge via interactions in small group settings of specialized individuals, mentoring programs, or mind maps developments.

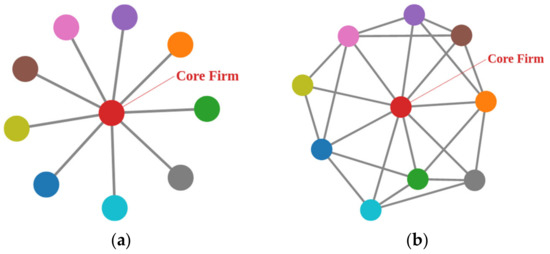

Dyer and Nobeoka presented the case of Toyota as a high-performance knowledge-sharing network [25]. They noted two dilemmas to be resolved before deploying a knowledge management initiative in a supply chain: (1) motivate supply chain members to share valuable knowledge and (2) retain supply chain members from exiting after having acquired knowledge. Socialization, as also analyzed by Nonaka and Takeuchi [20], can be observed in the Toyota case, as highlighted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Evolution of socialization in a knowledge-sharing network: from the initiation phase (a) to the mature phase (b) in the case of Toyota (adapted from [25]).

Knowledge management is a key lever to enhance the learning capabilities of an organization and to support a more sustainable competitive advantage through the knowledge value chain and the learning organization [19,25]. Just as the learning organization is argued to be competitively superior to a more traditional organization, the learning supply chain would be superior to a more basic integrated supply chain. This is also the case for food supply chains which moved towards learning supply chains defined by Peterson [22]. Indeed, as the concept of supply chain management began to rise and the performance of logistics operations considered as a strategic stake for companies as stated by Christopher [26], a growing body of work began considering knowledge management as a distinguishing indicator between best value supply chains and traditional supply chains [22,27], even if knowledge sharing remains viewed as a “nontrivial process” [8].

For Corso et al. [28], even if food industry firms have implemented many collaboration solutions in the 1990s to reduce the stocks and the bullwhip effect [29], the academic contributions should also study how knowledge is shared among supply chain members. Indeed, for Fisher [30], food supply chains inefficiency could be explained by the adversarial relations between supply chain partners. Archer and Wang pointed a shift from an organizational focus to an inter-organizational focus, where several organizations are members of the food supply chain, increased interest in knowledge management initiatives [31], particularly in a context of traceability becoming a legal obligation throughout the world in the early 2000s [32,33,34]. Moreover, for Peterson, as consumer concerns for food safety, environmental impact, freshness, and variety have grown, actors of the supply chain shifted from transactional to relational coordination [22]. Such a shift gave rise to more integrated supply chains from customer needs to supplier constraints, with tighter coordination and knowledge sharing.

The needs that knowledge sharing has to answer for food supply chains concern not only logistics but also sales, operations, quality, and consultation [28]. Relying on three cases of Italian food organizations, Corso et al. observed in [28] that digital solutions can provide communication between two applications (application-to-application, A2A) or between a user and an application (user-to-application, U2A). Whereas A2A solutions support the codification and standardization of knowledge by making it explicit, U2A solutions focus on socialization through communities enhancing tacit knowledge and its sharing. Pragmatically, the first step for organizations is then to identify activities needing support and for each the kind of needed focus: externalization or socialization of knowledge?

The non-profit organizations that are in charge of food aid in France comprise very heterogeneous associations: from small local associations managed by very few volunteers to large international organizations with thousands of members (paid or volunteers) and many local branches. For the biggest ones, some have a very centralized structure (such as the “Restos du cœur”) and others are very decentralized with a federal structure (such as the French Federation of Food Banks—FFBA). Despite the differences in their organization, they all share the same need to well manage their scarce resources to produce the best social value. As pointed by Rousseau, to survive, these organizations must also integrate the resources and skills that allow them to demonstrate their mastery of management techniques [35]. The issues surrounding the achievement of productivity gains are at least as important in these organizations, which have more limited financing capacities than large groups and are certainly more vulnerable to environmental factors.

Knowledge is one of the most important resources to manage in these organizations because it is not only a lever to achieve effectiveness and efficiency objectives in day-to-day operations, but it is also the driver of many social innovations. The challenge of knowledge management is all the more important in these organizations, where most of the manpower is voluntary. For Lettieri et al., despite their high motivation, volunteers may have heterogeneous experiences, a non-continuous presence, and a high rate of turnover [36]. But for the most part, food aid supply chains remained outside these schemes involving knowledge management, possibly due to a lack of resources and expertise to implement them.

Recently, the World Food Programme (WFP) made a call in “shaping communications to share knowledge more widely, including with affected populations and beneficiaries”, seeking to emphasize “inclusivity, participatory and people-centered approaches” [37]. Such a call is consistent with the recent rise of interest we observed in the literature when bridging knowledge management and food aid logistics.

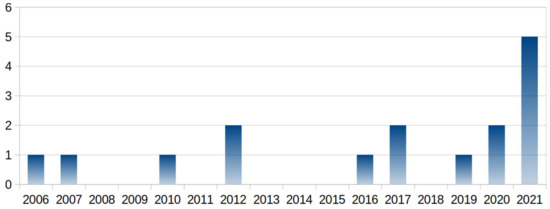

Indeed, a systematic literature review through Scopus with the request “TITLE-ABS-KEY (knowledge AND management AND food AND aid AND (logistics OR (supply AND chain)))” led to identifying only twenty-one articles that were published between 2006 and 2021, the majority of which at the end of this period. After studying their abstracts, we excluded five irrelevant articles (children interest in healthier food, sheep production, etc.) and noted ten articles focusing on food supply (FS), six on knowledge management initiatives (KM), four on humanitarian aspects of food supply (Hu.), four on food waste (FW), but only one on sustainable development and one on food donation. Table 1 presents a summary of this literature. It should be noted that the interest of academics in knowledge management and food aid logistics altogether as a whole is quite recent (2006) and has particularly grown in 2021 (see Figure 3), probably due to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Table 1.

Knowledge management and food aid logistics: a summary of prior literature showing recent interest in food supply (FS), knowledge management (KM), humanitarian (Hu.), and food waste (FW).

Figure 3.

Knowledge management and food aid logistics: recent literature showing recent growing interest in food supply, knowledge management, humanitarian, and food waste.

According to the World Food Program, food aid logistics also consider such a question of externalization or socialization of knowledge [38]. Sharing knowledge becomes then a matter of techniques, channels, and products deployed particularly for specific tasks and generally to ensure a common understanding by mitigating meaning variance [39] across members of the food aid supply chain (Table 2).

Table 2.

Knowledge sharing in the World Food Program: a matter of techniques (adapted from [37]).

Besides the quite optimistic philosophy of knowledge management, where knowledge has to be and could be shared by every member of the organization, authors such as Peterson provide a more pragmatical view of knowledge management in food logistics [22]. For him, the fact that certain dominant firms control the proprietary knowledge and the tradition of unintegrated relationships between supply chain members remain two significant barriers for socialization within supply chains. Controversy remains then open on the impact that digital tools for knowledge management might have in dignified and sustainable food aid logistics. This raises the question of dignity and the sense that this concept has from an individual, relational, and institutional point of view.

2.3. Dignity in Food Aid

As stipulated by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) of the United Nations, the right to adequate food is crucial to the enjoyment of all human rights, particularly the right to health, to life, to access water, to adequate housing, and to education [2]. The key elements of the right to food listed by the OHCHR (availability, accessibility, adequacy, and sustainability) are the same as those stated for the food security conditions by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations [3]. They highlight the multidimensional nature of food insecurity, namely:

- Availability, which refers to a quantitative dimension and is related to hunger and to the paradoxical question of food waste [55].

- Accessibility, which refers both to the economic accessibility (financial capacity of households to acquire foodstuffs) and the physical accessibility (proximity between populations and foodstuffs).

- Regularity (continuity) of access to food, which refers to the fact that food security must be stable over time. For some people, food insecurity is transitional (critical period of life, specific crisis, natural disasters, pandemics, etc.), whereas for others, it is permanent (e.g., structural low incomes).

- Quality of food and usage conditions, which refer to the intrinsic quality of foodstuffs (health, nutritional, and organoleptic properties) and to the logistical capacity of individuals to prepare safe and nutritious meals that meet their nutritional needs (related to housing concerns).

- Preferences, which refer to the necessary match between available food and the eating habits and tastes of individuals (social, cultural, religious, etc.).

- Social role, which refers to the role of food aid as a gateway to social inclusion. Food insecurity is rarely the only fragility suffered by food aid beneficiaries. Therefore, food aid as a lever of the fight against food insecurity must be associated with more global actions towards social inclusion and dignity of people.

The relationship between dignity and food processes is recognized by many researchers, such as Bedore and Kato, as critical and understudied [56,57]. Throughout the world, many are calling to design food systems promoting human dignity, i.e., considering dignity as crucial not only for life quality but also for health. Regardless of food aid, dignity is often regarded as socially developed, resulting from social interactions and realized through social behavior [58]. For Hodgkiss [59], the construction of dignity primarily relies on social relations.

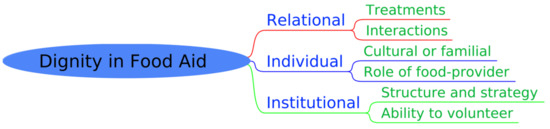

Very recently, Herrington and Mix [60] proposed a study on the social construction of dignity through daily food experiences in a food aid community. Through qualitative interviews and ethnographic field study, they observed that, when discussing experiences related to dignity construction, individuals perceived three “social arenas”: (1) relational, (2) individual, and (3) institutional (Figure 4). Such a pragmatic analysis of dignity construction in food aid definitively appears relevant to better understand the initiatives we studied in France. These three social arenas resulting from qualitative and field studies from Herrington and Mix [60] will now be detailed.

Figure 4.

Dignity in food aid, a matter of relational, individual, and institutional arenas (adapted from [44]).

First, the relational arena corresponds to experiences related to social encounters. The question of food access seems to have the strongest influence on the construction of dignity in this arena. During the food procurement process, participants in the study differentiate relations between “treatments” and “interactions”. The former degrade their sense of dignity, the social encounter being asymmetrical, whereas the latter elevate their sense of dignity, with relationships such as recipe exchanges or friendships that continue even outside the food aid space. As already discussed by Mann and by Miller and Keys, interacting with peers accessing food in these spaces, i.e., through symmetrical social encounters, preserve or promote dignity [61,62].

Second, the individual arena corresponds to experiences related to self-identity. Participants reported food as a component of their identity, and Berger and Luckman already noted that one’s sense of identity is attached to one’s sense of dignity [63]. In the individual arena, dignity is elevated through two dimensions: cultural or familial traditions, which develop certain familial traditions and identity, and the ability to act as a food provider, which grants recognition to the ones who made food available for their families. This is clearly consistent with Nordenfelt, who already stated that dignity is attached to the ability to live with autonomy [58]. Many participants in the study of Herrington and Mix reported that providing food for others implies more than nutrition or basic sustenance and is a way to elevate not only their own but also others’ dignity [60].

Third, the institutional arena corresponds to experiences related to organizations that impact dignity. Participants reported here two dimensions: the structure of these organizations and the ability to volunteer in these organizations. Indeed, some organizational structures and strategies elevate dignity by replicating the shopping experience, with choice, layout, opening times, etc. A study from Seltser and Miller on homeless shelters showed that excessive rules negatively impact dignity; consequently, relaxed requirements and administrative procedures elevate the dignity of the homeless [64]. Additionally, every participant in the study of Herrington and Mix reported that having the choice in the types and amount of received food significantly elevated their dignity [60]. Finally, volunteering after having used food aid services has been reported as offering a sense of empowerment that elevates dignity. Some of the shame to relying on food aid is reduced by giving back, and a feeling of ownership in the organization enhances pride as well as dignity. Observations we made as closely as possible to real fields will now be presented and discussed through three initiatives in France.

3. Three Initiatives of Food Aid Organizations in France

In this section, we introduce inspiring initiatives of three French associations that, by using some features of knowledge management and digital systems, developed innovative projects towards the modernization of food aid organizations. We show how dignity in food aid logistics is also a knowledge management and digital matter. First, we present the initiative of the charity ReVivre and its AlimHotel decision support system, developed to improve the food situation of people housed in hotels. Second, we present the initiative of the French Federation of Food Banks—FFBA and its forthcoming Geographic Information System (GIS) aimed to solve the problem of the so-called “white zones”, i.e., areas of the territory that are not covered by a food aid network. Third, we present the initiative of the HopHopFood food aid association and its smartphone application that connects potential beneficiaries with food providers fighting against food waste.

3.1. The ReVivre Association and a Decision Support System

ReVivre is a food aid organization as well as a social enterprise for labor market integration in the field of logistics. It is very active in the Île-de-France region, which is those of Paris and France’s most populous region. It has a peculiar place in the food aid associations ecosystem because it defines itself as a logistics service provider and as a wholesaler in food aid supply chain that collects food products (donations from manufacturers and pick-ups of unsold foodstuffs) or buys them, what is an important lever in balancing the food parcels for nutritional and variety purposes (see Figure 5).

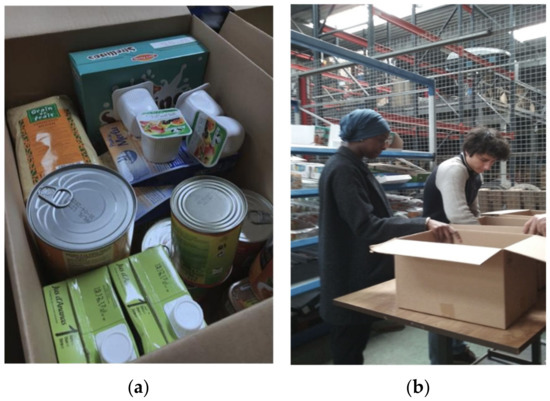

Figure 5.

Example of a food parcel for children (a) and photo of the preparation site (b).

Moreover, as ReVivre mixes an aid organization structure and a social enterprise for labor market integration in the field of logistics, it can mitigate some of the issues linked with relying entirely on a volunteer workforce. This implies, however, a need for funds for wages. Its small size gives ReVivre considerable operational agility that translates into a great ability to develop social innovation projects in relation to food aid. Among these projects, we wish to shine light upon an especially interesting one: the AlimHotel project.

AlimHotel is a service developed by ReVivre to improve the food situation of people housed in hotels by the State in the Île-de-France region. The SAMU Social, which is the humanitarian emergency service in France, is a user of this service. The origins of AlimHotel lie in a 2013 study from the SAMU Social Observatory. This study, called ENFAMS (ENfants et FAMilles Sans logement personnel en Ile-de-France, meaning “children and families without personal accommodation in Ile-de-France”), was conducted among people living in emergency shelters, mostly in hotels. Half of the respondents were single-parent families, and a majority of them were migrants. Such a study leads to a clear statement: 86% of respondents were food insecure; among them, 11% suffered from severe food insecurity [65]. The AlimHotel project was thus launched by the SAMU Social and funded by the Île-de-France region to enhance the food situation of these people.

Through the lens of food aid, people in emergency shelters or housed in hotels present specific vulnerabilities that make access to a proper diet more complicated. They particularly suffer from limited accessibility and usage conditions of food because these hotels are often in isolated suburbs, and they do not offer any access to a kitchen to cook meals. The kind of products that can be offered is consequently limited, and, knowing that this public is mostly composed of single mothers, we can easily imagine the difficulties implied by this situation.

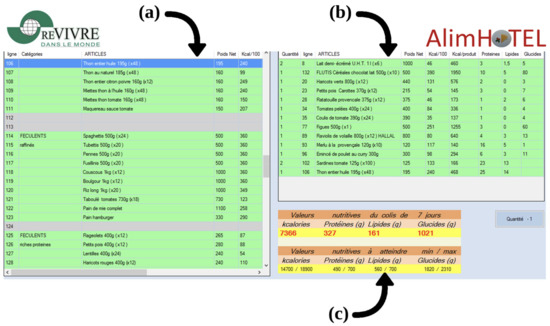

In addition to the proposal of a logistical service for weekly deliveries of food parcels, the association created a digital tool to assist the preparation of the parcels and weekly menus. This decision support system (see Figure 6) has been created by two volunteers, a nutritionist and a computer scientist. It helps to compose meal parcels by taking into account:

Figure 6.

The AlimHotel decision support system supporting the preparation of parcels: foodstuffs’ base (a), current selection (b), calorie calculation, and balance check (c).

- The food balance and the PNNS recommendations (French National Program for Nutrition and Health). Particularly, it tries to favor seasonal fruits and vegetables (that can be eaten raw or that are easily cooked in a kettle because the recipients cannot cook in their hotels), completed by simple proteins (milk cartons, various canned fish, etc.).

- The available inventory (possibility to substitute products to respect the nutritional balance of offered parcels).

- The composition of the recipient’s family, food aid is targeted by age range (parcels for adults, for children, and for babies).

- Dietary habits of recipients, for instance, not giving away pork to Muslim families nor meat to vegetarians.

Finally, this software gives recipients a rotation of foodstuffs: depending on the family, a rotation of four typical parcels is planned to avoid recurring meals several weeks in a row. Indeed, nutritional balance is not enough, and the AlimHotel digital project enhances dignity in food aid by considering that people need not only to eat but also to want to eat, and sufficient diversity is an important factor for it.

This project is considered by its stakeholders as a real social innovation enhancing dignity in food aid. The impact assessment that has been made was very encouraging. During the COVID-19 health crisis, the French State called for ReVivre and the AlimHotel service to manage the crisis due to the rise in emergency shelter admissions.

3.2. The French Food Bank Association and a Forthcoming Geographic Information System

The French Federation of Food Banks—FFBA is an important aid organization founded in 1984 following the model of the American Food Banks. It is a federation of seventy-nine regional food banks and thirty-one local subsidiaries, creating a network that covers the totality of the French national territory.

The mission of the FFBA is to fight against precarity and food waste by collecting foodstuffs that are still safe for human consumption but cannot be sold anymore. It collects the FEAD (European fund, see Section 2.1) as well as foodstuffs and plays the role of wholesaler and logistics provider for smaller food aid associations. In 2020, the FFBA stated that 112,500 tons of foodstuffs were collected and redistributed to six thousand partner organizations and communal social centers. The latter two then redistribute them to needy people. From this 112,500 tons, the FFBA saves 75,000 tons from destruction. In the span of 35 years, the equivalent of four billion meals was collected and distributed through food banks.

However, much like a lot of associations, the FFBA recognizes that the coverage of the territory with food aid remains unequal between urban and rural territories. Indeed, while rural areas represent 80% of the national territory, the offer for food aid is concentrated in urban and peri-urban territories. Therefore, due to evident logistical constraints, food aid suffers from the existence of so-called “white zones”, i.e., areas where classic distributions and aid networks cannot take on precarity and food insecurity. The term “white zones” is borrowed from the telecommunications sector and describes areas where there is no mobile phone network coverage. These areas are isolated rural territories.

The associations observe that poverty in rural territories is an increasingly important problem and isolation is an aggravating factor for this precarity. This perceived isolation is due to the social and geographical distance to food aid structures but also because of the absence of local shops (especially hard discount stores) as well as the absence of public transport allowing people without vehicles to go shopping or take care of administrative matters. To this weakness, we can add a lack of communication due to the lack of sufficient local branches.

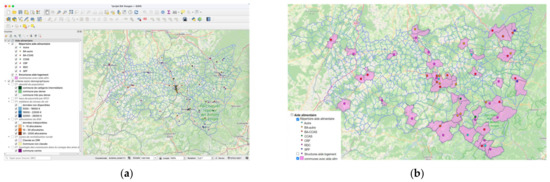

The FFBA launched a project to support initiatives to develop food solidarity in the rural world. The aim of this still-in-progress project is to create a digital tool based on cartography. Such a tool will take advantage of the features offered by a geographic information system (GIS) to understand and better answer to the issue of these white zones.

This project, developed first for the department of Les Vosges (East of France) as a pilot area, is aimed to be replicated in other rural territories. The implementation of this cartography aims to visualize the white zones. It also aims to have this cartography enriched by more criteria than only “food aid availability”. Indeed, characterizing these situations of isolation and visualizing them should enable to identify levers for actions to improve the situation and to be a starting point to propose innovative solutions to this problem. A study has been conducted with various actors in the field concerning the interest that they have in such an interactive and updated map of food aid in their area [66]. It revealed the following points for the actors:

- They want to be able to differentiate the mapping tool according to the target audience (decision makers and beneficiaries) and to include as many details as possible for each structure (hours, contact, etc.).

- They want to enrich the information with other services (e.g., emergency shelters), whose residents often also use food aid.

- They want to have an exhaustive and complete vision (i.e., all associations on a whole territory) because there are already existing cartographies focusing on a particular association (such as ReVivre or the Restos du cœur). The idea is then to offer a multi-association initiative that is not focused on food aid but rather on all kinds of services, initiatives, and resources for people in difficulty (as, for example, the soliguide.fr Webpage).

The first version of this map was made relying on the QGIS software (see Figure 7). This is a GIS that can overlay several layers of information. Then, the proposed cartography can localize food aid services in relation to various data like the poverty rates, the number of welfare recipients, the population density, etc. Aggregating this information enables us to visualize the distribution of food aid on an area in several ways: depending on the structure, the type of assistance provided, the opening hours, etc.

Figure 7.

A geographic information system aggregating information (a) and showing distribution inequalities (b). (Source: https://banquealim88.github.io/projetBA88/, accessed on 25 November 2021).

The tool also allows the map to be exported and made available to any audience from a hyperlink (via the Github platform), which would make it accessible to different users. As the map is interactive, it can be used to better orient recipients according to their needs and the nature of the activity of the listed help center. Indeed, it is possible to zoom in to see in detail the location of the distribution points in the cities, and when one clicks on a point, it displays a set of information related to the food aid system (precise address, type of aid provided, opening hours, name of a contact person, etc.).

The resulting map shows any eventual imbalance in the distribution of structures with regards to the needs. Because the tool offers the possibility to view the structures, not only as points on a map but also with their range of action (linked, for instance, with their size or the availability of means of transportation), one can have a more realistic vision of the food aid availability on a territory.

The goal of this map is not necessarily to open new distribution centers but also to think about an innovative solution like structures pooling or mobile solidarity grocery stores. Indeed, as the GIS offers the possibility to overlay several layers of information, the FFBA added criteria like the availability of transportation networks and the distribution of local food shops (hard discount shops notably). This last element has been highlighted as an aggravating factor for the isolation of the population affected by food insecurity in rural territories.

The functionalities offered by the GIS tools are powerful, and while they would not solve the problem of accessibility to food aid, they enable us to visualize it and help characterize it in order to provide solutions. Nevertheless, the potential of the tool is obviously subject to the quality and availability of the information. We observed that different actors and stakeholders hold the information necessary for the proper use of the tool. Some are public data, others are held by social centers, and others by associations or even by the beneficiaries. It will therefore be necessary to go beyond the traditional boundaries of food aid organizations in order to be in a sharing system. The recent management of the COVID-19 health crisis has at least made it possible to initiate this pooling and to reveal its benefits in many territories.

3.3. The HopHopFood Association and a Smartphone Application

HopHopFood is a food aid association created in 2018. The aim is to connect through digital means people who need food with providers (individuals or merchants) who have surplus foodstuffs. Thus, HopHopFood is positioned on the creed of the fight against food waste for the benefit of disadvantaged populations.

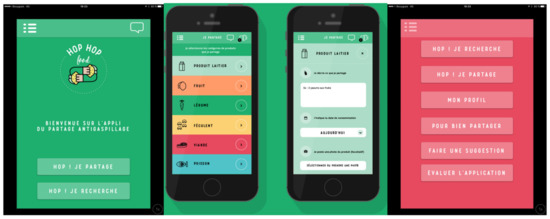

The association covers several missions through its different activities. We focus here on its activity linked to the smartphone application it has developed, which allows people with modest incomes to recover, under favorable conditions, unsold goods from local shops around them.

HopHopFood started from the following assessment: people benefiting from food aid are only a fraction of people suffering from food insecurity. Indeed, many people who could qualify for food aid do not use it for various reasons such as administrative difficulties in accessing this aid, feeling of shame, lack of information on their rights, and many other objectives, as well as subjective reasons. In France, there were in 2015 nearly four times fewer food aid users than people in a situation of food insecurity estimated by the Inca study [67].

HopHopFood targets populations that do not benefit, either voluntarily or involuntarily, from the classic food aid system, in particular students and migrants. HopHopFood describes them as people living in “little deprivation”, who often fall off the radar of traditional food aid systems. The goal is to offer them a solution adapted to their profile, and that will encourage them to use this much-needed assistance. This population, often young people using digital technology and equipped with smartphones, is estimated by HopHopFood to be around 10 million people.

Among the solutions developed by HopHopFood, we will focus on the business-to-consumer offer that enables volunteering sellers to propose a part of their unsold foodstuffs through food aid. Such a smartphone application operates with the same principles as the famous Too Good To Go application, with the difference that HopHopFood is a non-profit organization.

Different stores (retailers, restaurants, butchers, bakers, etc.) that have unsold foodstuffs make them available on the HopHopFood application (Figure 8). Food aid beneficiaries can connect to the app with a specific access code that has been delivered by social workers. Thus, a beneficiary with an access code selects the desired available products, puts them in his/her virtual basket, and goes to the store to pick them up (during opening hours or at times indicated by the merchant). HopHopFood states that 70% of users of these codes are students.

Figure 8.

The HopHopFood smartphone application: “Hop! I share”, “Hop! I search”. (Source: www.hophopfood.org, accessed on 25 November 2021).

Users of this service do not pay for the parcels they collect. Shopkeepers are paid through fiscal compensations in accordance with the Garot and Egalim French laws [13,14]. As explained in Section 2.1, in France, donating unsold stocks to food aid associations enables the donor to get 60% of the value of the donation back as a tax deduction. In return, the shopkeeper promises to donate to HopHopFood 50% of this tax deduction; this enables the association to keep developing and stay economically viable.

When HopHopFood recipients go to merchants to pick up the parcels they ordered, they present their smartphone with their proof of order, and the merchant enters their specific code. This allows then the merchant to declare the donated food items, leading to automatically creating the administrative form to get the tax deduction. For recipients, this way of collecting unsold food is considered much less stigmatizing than going to food aid distribution centers to get a food parcel.

As previously described, the same tax deduction system is used by food aid associations to collect unsold goods from food companies and shops (the so-called “pick-up system”). In Section 2.1, we highlighted the many limits, especially at the logistics level and on the level of quality and diversity of the goods offered. This digital solution through the smartphone application proposed by HopHopFood presents a lot of advantages.

First, contrary to how pick-up works, in this system, there are no products excluded from being given away (meat, seafood, etc.). Indeed, for practical food safety reasons, the most expensive products cannot be donated to food aid through pick-up. In the case of the HopHopFood service, these restrictive rules do not apply because the supply chain towards beneficiaries is similar to classical clients.

Second, as previously described, another shortcoming of the classic pick-up system is its logistical complexity. It mobilizes human and material resources to collect the foodstuffs, store them, prepare the parcels, and distribute them, all that in a short time because of expiration dates. The digital system mitigates such a shortcoming for food aid associations.

Another advantage of the digital system is that the back office is extremely detailed and makes it possible to build very detailed key performance indicators allowing the offers to evolve. For example, in order to be consistent with HopHopFood’s desire to fight against food waste, time slots have been set up: priority is given to people who have access to food aid (with a code provided by a social worker), and then the access is opened to other people who consider themselves to be in need (without code, i.e., without being registered by a social worker). HopHopFood is still developing new offers and services, taking advantage of the digital features offered by its smartphone application.

4. Discussion and Limits

Through a description of food aid logistics in France (see Section 2.1), we pointed out some of its limits and how they might be answered with knowledge management initiatives for food aid logistics (see Section 2.2). The question of enhancing dignity in the organization of food aid arose then when we observed not only a definition of food security in the literature insisting on availability, accessibility, adequacy, and sustainability (see Section 2.3), but also the reality on the ground where the “social […] access” and “food preferences” specifications of food security were not trivial at all.

4.1. Discussion on the Three Considered Initiatives

Herrington and Mix proposed three social arenas of dignity in food aid: (1) relational, (2) individual, and (3) institutional (see Section 2.3) [60]. These arenas result from a quantitative and ethnographic field study in the United States and are totally consistent with observations we have done within food aid associations in France. We argue that the social acceptability of food aid is crucial to ensure a dignified and consequently more sustainable food security situation. The social arenas from Herrington and Mix are used in the following to discuss the initiatives presented in Section 3 and highlight that dignity in food aid logistics is also a knowledge management and digital matter. Table 3 summarizes the discussion presented in this section.

Table 3.

Dignity in food aid logistics is also a knowledge management and digital matter: three initiatives in France.

In the case of ReVivre, the preparation of food parcels is digitalized and considers not only the context of the beneficiaries (e.g., family living in a hotel with babies) but also their consuming habits or cultural diets (e.g., no meat, no pork), their preferences (e.g., usually returned unused foodstuff), and ensures a rotation in delivered food parcels. The digital system allows the ReVivre association to manage pushed flows of foodstuffs in a pulled manner (see Section 2.1) through the management of knowledge on beneficiaries (a kind of “delayed differentiation” supply chain as defined by Anand and Girotra [68]). Indeed, as a charity association, we noted that ReVivre massively relies on volunteers, whose presence and continuity are difficult to ensure. In the relational arena of dignity in food aid, treatments are clearly improved through the digital system and knowledge management it enables: the ability to choose foodstuffs as well as the automatic rotation of foodstuffs depending on knowledge on beneficiaries enhance dignity. In the institutional arena, structure and strategy are also improved through the digital system: volunteers collect once and for all knowledge on beneficiaries that is stored in the system and shared with future volunteers who might be different. Food access is consequently eased with a unique entry point for sometimes redundant and downgrading administrative procedures, which enhances dignity. Finally, ReVivre easily allows its beneficiaries to volunteer by allowing them to give back unused foodstuff to other beneficiaries, another way to enhance dignity in food aid, according to Herrington and Mix.

In the case of the FFBA (French Federation of Food Banks), the willingness to share data between several associations is the first prerequisite for an effective geographical information system. Indeed, such an initiative exists in several associations independently, but it is effective if and only if the amount of data is enough to ensure relevancy and usefulness for beneficiaries. We argue that logistics pooling, in the sense of Morana et al. [69], could definitively increase the efficiency of the organization of food aid regarding our observations in France. In the relational arena, the FFBA project allows potential beneficiaries to see and choose available associations geographically, which enhances dignity. In the individual arena, the role of food provider is impacted: because of a lack of communication, potential beneficiaries were often unaware of the existence of local and near associations. The digital system provides such geographical information, impacting the role of food-provider for beneficiaries. Finally, in the institutional arena, the structure and strategy dimension is improved through analyses on the geographical distribution of food aid allowed by the digital system. Such a system will be used as a decision support system allowing to improve the distribution of food aid structures in a geographical area, enhancing the dignity of beneficiaries accessing these structures.

In the case of the HopHopFood smartphone application, the digital system aims to make the food aid access similar to a classical “click and collect” shopping experience. Unsold foodstuffs from local shops around beneficiaries are made available to them through the smartphone application. The service is free for them, and shops are paid with fiscal compensation because they donate unsold stocks to an aid organization. In the relational arena of dignity in food aid, treatments are definitively improved by the digital system: they are made as much as possible similar to a classical shopping experience for beneficiaries. In the individual arena, HopHopFood targets populations that do not benefit from the classical food aid system. Some beneficiaries are, for example, students witnessing that “as a master’s student, I never imagined that I would queue at the Red Cross to eat”. Allowing beneficiaries to access a food aid solution adapted to their “little deprivation” profile enhances dignity. Similarly, in the institutional arena, the ease of access to food aid through the digital management of administrative procedures enhances dignity. Indeed, fiscal compensations for the shops ensure the commitment of food providers donating unsold stocks with a feeling to contribute to food aid, which enhances dignity for everyone.

4.2. Implications and Limits

Much research is devoted to helping food companies optimize their supply chains with digital and knowledge management systems. So little talk about how to modernize food aid supply chains, yet the world continues to be food insecure. Food insecurity occurs when some individuals are not in a situation of food security. Less intuitive is the idea that this is also true in developed countries. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, food security is achieved when “all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” [3]. Table 4 proposes an overview of the three food aid organizations’ initiatives that were presented in the previous section regarding not only the digital component they involve but also the characteristics of the right to food definition and the food security components (see Section 2.3).

Table 4.

Characteristics of right to food and food security addressed by the initiatives and the digital tools.

Digital tools are a way to modernize the food aid system. They allow overcoming some of its limitations and better fit to food security characteristics, as highlighted through the described initiatives. Nevertheless, the digital tools are also an opportunity to propose new services in order to improve the so-called “going-to” for certain populations (e.g., bringing people who do not wish to use the system as it currently exists to benefit from food aid). They would make it possible to relieve the volunteers in the associations from certain tasks so that they can focus on the accompaniment of beneficiaries with important needs. Furthermore, more digitalized processes can make it easier for different caritative associations to share knowledge and data about their activities, to share best practices, pool logistical infrastructures, and pool data related to the beneficiaries. This would, for example, avoid the need for beneficiaries to make new applications each time they contact a new association. Why not imagine a national or regional platform? Such a unified and unique entry point in the food aid system would then direct beneficiaries according to their situation towards different structures adapted to their case and according to the means and availabilities of the social structures.

Yet one must be aware that digitalization is not all that deprived people need. Table 4 shows that the social role characteristic of food security, associated with the social inclusion of deprived people, is not directly addressed by the digital projects of the three initiatives considered in this article. If we consider the broader sense of the social role of food security, the food aid can be a gateway for a more comprehensive approach towards social inclusion, meaning housing, health, hiring, etc. This comprehensive approach needs professional skills that are held by social workers in food aid structures notably. Therefore, the analysis of the initiatives proposed in Table 4 highlights the limits of “all-digital” solutions and the importance of the role ensured by social workers.

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Food aid in France relies on the charitable sector that in turn relies on foodstuff donation. We highlighted some shortcomings of such a system by pointing out how food aid supply chains become a real brainteaser for food aid associations and for the great number of volunteers mobilized.

As researchers in management and information systems, we wondered about the feasibility of transferring knowledge and know-how from traditional organizations to these non-profit organizations. As far as food supply chain management is concerned, themes such as digitalization and knowledge management have demonstrated their benefit [70] or impact on performance [71]. The difference is that the specificity of the “customer” at the end of this food aid supply chain leads to consider the performance not only in terms of efficiency or effectiveness but also through unusual dimensions of performance, in this case: the dignity of the people helped.

We then tried to propose an analysis of three inspiring initiatives of French food aid associations that propose social innovations to modernize food aid. To do so, we used a reading grid proposed by Harrington and Mix [60] to associate the issue of dignity with the implementation of digital tools that impact knowledge management in these organizations. These initiatives reveal an undeniable modernization potential and allow us to argue our proposition that the question of dignity in food aid logistics is also a knowledge management and digital matter.

These initiatives also raise many questions related to the sustainability of the global food aid system we described. This system has the merit of being an adequate response to specific forms of vulnerability that lead individuals (or groups of individuals) to a situation of food insecurity, e.g., people living in hotels in the case of ReVivre, isolated people in rural areas in the case of the FFBA, and people in “little deprivation” in the case of HopHopFood. Finally, these responses, as interesting as they are, perpetuate the dominant logic in the approach of food insecurity: the free distribution of food (partially issued from food waste). These modernizing solutions enhance dignity in a global system that remains unworthy. Indeed, as pointed by Cavaillet et al., in doing so, we place ourselves in a curative logic to repair the failures of a system instead of privileging a preventive logic to avoid the occurrence of this food insecurity [9]. New proposals, studied by Gundersen and Cavaillet et al., are emerging and calling for a universal income for food that would make it possible to address the root causes of food insecurity, at least for some of the beneficiaries [9,72].

Author Contributions

Both authors have contributed equally to the manuscript. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the students and the food aid organizations who provided access to their field data and digital tools. They also thank the editors and reviewers for their time, helpful comments, and guidance. This publication was supported by AgroParisTech.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2021. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021/ (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- UNCHR. The Right to Adequate Food, Human Rights Fact Sheet Series No. 34. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/FactSheet34en.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021. In Transforming Food Systems for Food Security, Improved Nutrition and Affordable Healthy Diets for All; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cb4474en/cb4474en.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Radimer, K.L. Understanding Hunger and Developing Indicators to Assess It. Ph.D. Thesis, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Segura, M.I.; Medina-Dominguez, F.; de Amescua, A.; Dugarte-Peña, G.L. Knowledge governance maturity assessment can help software engineers during the design of business digitalization projects. J. Softw. Evol. Process. 2021, 334, e2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, J.; Atherton, R. Rhetorics of data in nonprofit settings: How community engagement pedagogies can enact social justice. Comput. Compos. 2021, 61, 102656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosic, B.; Zivkovic, Z. Knowledge Management and Innovation in the Digital Era: Providing a Sustainable Solution. Adv. Econ. Bus. Manag. Res. 2019, 108, 193–197. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, R.L.; Corso, M. From continuous improvement to collaborative innovation: The next challenge in supply chain management. Prod. Plan. Control 2005, 16, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaillet, F.; Darmon, N.; Dubois, C.; Gomy, C.; Kabeche, D.; Paturel, D.; Perignon, M. Vers une Sécurité Alimentaire Durable: Enjeux, Initiatives et Principes Directeurs. Rapport Terranova. 2021, 109p. Available online: https://tnova.fr/societe/alimentation/vers-une-securite-alimentaire-durable-enjeux-initiatives-et-principes-directeurs/ (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Darmon, N.; Gomy, C.; Saidi-Kabeche, D. La Crise du Covid-19 Met en Lumière la Nécessaire Remise en Cause de L’aide Alimentaire. The Conversation. 2020. Available online: https://theconversation.com/la-crise-du-covid-19-met-en-lumiere-la-necessaire-remise-en-cause-de-laide-alimentaire-140137 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Bazin, A.; Bocquet, E. Rapport D’information Fait au nom de la Commission des Finances sur le Financement de L’aide Alimentaire, French Senate. 2018. Available online: https://www.senat.fr/rap/r18-034/r18-0341.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Cour des Comptes. Rapport Sur Les Circuits et Mécanismes Financiers Concourant à L’aide Alimentaire en France, French Court of Auditors. 2009. Available online: https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/commissions/cfin-enquete-CC-aide-alimentaire.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- République Française. Loi no. 2016-138 Relative à la Lutte Contre le Gaspillage Alimentaire. Journal Officiel “Lois et Décrets” No. 0036 du 12 Février 2016. 2016. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000032036289/ (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- République Française. Loi No. 2018-938 Pour L’équilibre des Relations Commerciales dans le Secteur Agricole et Alimentaire et une Alimentation Saine, Durable et Accessible à Tous. Journal Officiel “Lois et Décrets” No. 0253 du 1 Novembre 2018. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000037547946 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Pyke, D.F.; Cohen, M.A. Push and pull in manufacturing and distribution systems. J. Oper. Manag. 1990, 9, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DGCS. Programme Opérationnel Français FEAD 2014–2020, Execution Report from the Direction Générale de La Cohésion Sociale (DGCS). 2019. Available online: https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/rae_2019_publie.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- FFBA. Annual Activity Report of the French Federation of Food Banks. 2019. Available online: www.banquealimentaire.org/sites/default/files/2020-07/Rapport%20annuel%20Banques%20Alimentaires%202019%20BD.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Muhialdin, B.; Filimonau, V.; Qasem, J.; Algboory, H. Traditional foodstuffs and household food security in a time of crisis. Appetite 2021, 165, 105298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.C.; Yang, J. Knowledge value chain. J. Manag. Dev. 2000, 9, 783–793. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Arduin, P.E.; Kabeche, D.; Sali, M. Innovative Solutions for Information and Knowledge Systems Security: A Total Quality Management Perspective. In ECKM 18th European Conference on Knowledge Management; Academic Conferences and Publishing Limited: Barcelona, Spain, 2017; pp. 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, H.C. The “learning” supply chain: Pipeline or pipedream? Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2002, 84, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arduin, P.E.; Grundstein, M.; Rosenthal-Sabroux, C. Information and Knowledge System; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ives, W.; Torrey, B.; Gordon, C. Knowledge Sharing is a Human Behavior. In Knowledge Management: Classic and Contemporary Works; Morey, D., Maybury, M., Thuraisingham, B., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 99–131. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, J.H.; Nobeoka, K. Creating and managing a high-performance knowledge-sharing network: The Toyota case. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M. Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Strategies for Reducing Cost and Improving Service; FT Prentice Hall Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ketchen, D.J.; Hult, G.T.M. Bridging organization theory and supply chain management: The case of best value supply chains. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, M.; Dogan, S.F.; Mogre, R.; Perego, A. The role of knowledge management in supply chains, evidence from the Italian food industry. Int. J. Netw. Virtual Organ. 2010, 7, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.L.; Padmanabhan, V.; Whang, S. Information distortion in a supply chain: The bullwhip effect. Manag. Sci. 1997, 43, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.L. What is the right supply chain for your product? Harv. Bus. Rev. 1997, 75, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, N.; Wang, S. Knowledge management in the network organization. In Proceedings of the 24th ITI International Conference on Information Technology Interfaces, Cavtat, Croatia, 22–24 June 2002. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament, Council of the European Union. Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 Laying Down the General Principles and Requirements of Food Law, Establishing the European Food Safety Authority and Laying Down Procedures in Matters of Food Safety. 2002. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2002/178/oj (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan. Guidelines for Introduction of Food Traceability Systems; Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries: Tokyo, Japan, 2003. (In Japanese)

- The United States of America Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act of 2002. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/107/plaws/publ188/PLAW-107publ188.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Rousseau, F. Réapprendre à conter: Genèse d’un entrepreneur social. Gérer Et Compr. 2007, 87, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lettieri, E.; Borga, F.; Savoldelli, A. Knowledge management in non profit organizations. J. Knowl. Manag. 2004, 8, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFP World Food Program. WFP Evaluation. Communications and Knowledge Management Strategy (2021–2026). Technical Report. 2021. Available online: https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000128399/download/?_ga=2.3054384.1832851998.1638121601-1903600514.1638121601 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- WFP World Food Program. Knowledge Management A Pillar of WFP’s Zero Hunger Strategy. World Food Programme Technical Report. 2016. Available online: https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000018916/download/ (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Arduin, P.E. On the measurement of cooperative compatibility to predict meaning variance. In Proceedings of the IEEE 19th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD), Calabria, Italy, 6–8 May 2015; pp. 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Blevins, P. Food Safety Regulatory Compliance: Catalyst for a Lean and Sustainable Food Supply Chain; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bryceson, K.; Ross, A. Habitus of informality in small scale society agrifood chainsfilling the knowledge gap using a socio-culturally focused value chain analysis tool. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2020, 25, 545–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.; Trimingham, R.; Wilson, G.T. Incorporating consumer insights into the UK food packaging supply chain in the transition to a circular economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, B.; Behnke, N.; Cronk, R.; Anthonj, C.; Shackelford, B.; Tu, R.; Bartram, J. Environmental health conditions in the transitional stage of forcible displacement: A systematic scoping review. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 762, 143136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Boeck, E.; Jacxsens, L.; Goubert, H.; Uyttendaele, M. Ensuring food safety in food donations: Case study of the belgian donation/acceptation chain. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filimonau, V.; Ermolaev, V. Mitigation of food loss and waste in primary production of a transition economy via stakeholder collaboration: A perspective of independent farmers in russia. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, C. Discontinuous wefts: Weaving a more interconnected supply chain management tapestry. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 2021, 57, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holguin-Veras, J.; Prez, N.; Ukkusuri, S.; Wachtendorf, T.; Brown, B. Emergency logistics issues affecting the response to katrina: A synthesis and preliminary suggestions for improvement. Transp. Res. Rec. 2007, 2022, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kembro, J. Implementing strategic stock to improve humanitarian aid response. Emerald Emerg. Mark. Case Stud. 2012, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manos, B.; Manikas, I. Traceability in the greek fresh produce sector: Drivers and constraints. Br. Food J. 2010, 112, 640–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMeekin, T.; Baranyi, J.; Bowman, J.; Dalgaard, P.; Kirk, M.; Ross, T.; Schmid, S.; Zwietering, M. Information systems in food safety management. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 112, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Guo, H. Visualization and analysis of mapping knowledge domains for food waste studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernndez, B.S.; Snchez, M.R. Sustainability in humanitarian supply chains: Perspectives and challenges [sostenibilidad de las cadenas de suministro humanitarias: Perspectivas y desafos]. Rev. Venez. De Gerenc. 2019, 24, 131–150. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A.; Francis, M.; Fisher, R.; Haven-Tang, C. The application of group consensus theory to aid organizational learning and sustainable innovation development in manufacturing enterprises. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 6, 307–312. [Google Scholar]