Abstract

This research analyzed the importance of competencies within the development of the cooperative system through the case study of the Tejemujeres Women’s Artisan Cooperative, for which a documentary and field investigation was conducted with a descriptive and explanatory scope under a mixed approach. The importance of cooperatives as tools of social cohesion has been considered due to the progress of their members, their strengthening of social capital, and generation of the necessary conditions to adapt to the demands of the place in which they operate. From this perspective, research tools such as surveys, interviews, and focus groups were implemented for a total of 85 participants of the entity under a census and incidental sample approach to analyze each of the responses under the Working With People model, from its dimensions: ethical-social, technical-business, and political-contextual. These responses have been collected in such a way that the skills of the most significant relevance to artisans are identified, which have allowed the strengthening of the cooperative system. The results demonstrate the level of incidence of a group of indigenous women from the rural area of the Gualaceo canton. The development of their skills has participated in the construction and implementation of a social model of company cooperative that—due to the complexity of its members and its environment—must face several scenarios to adequately articulate the social-business vision and achieve its sustainability over time.

1. Introduction

Humanity participates in historical structural changes at a productive, economic, environmental, and mainly social level. This has required rapid and constant adaptation with the sole objective of improving living conditions and contributions to productivity from a country in one way or another. Therefore, these changes have motivated people with low economic resources to stand out by joining their strengths, knowledge, and skills to achieve social and economic development in rural places or places that are unattractive to capitalist industry. In this context, cooperatives are generated that allow the generation of actions aimed at meeting social objectives from an interpersonal division of labor due to their organizational system, which is expressed in organizational structures and the relationships between them [1].

Indeed, cooperatives are recognized as essential actors in the economic and social development of a country, which has been vital for the fulfillment of the sustainable development objectives set by the United Nations Organization (UN). Through the inclusion of people from their communities, sustainable employment has represented a total of 279.4 million people worldwide dedicated to various activities and functions. Therefore, due to the diversification of the context of a cooperative, the International Organization of Industrial, Craft, and Service Production Cooperatives (CICOPA) identifies savings and credit cooperatives as accessible financial entities for people seeking financing to set up a business, access to education, or for some other basic need; with regard to services, entrepreneurs and producers seek to associate to educate themselves, learn new trends about their business, and develop new skills that contribute to their negotiating power [2,3]

In Ecuador, since the end of the 11th century, the philosophy of cooperativism was spread by the union and political and intellectual delegates as a way of life, which has included the joint work of people for a common family good or community since ancient times. Cooperativism in the country had a greater effect and motivation in the agrarian sector—sponsored mainly in the Sierra region—where, based on the first law of cooperatives, it focused on contributing to social purposes. Of those involved, non-profits were promoted by solidarity and economic improvement. In turn, within the first legal framework established in 1937, the internal and administrative processes of the cooperatives are detailed; the same ones still apply today. In short, the development of cooperatives has been backed by the law, which recognizes and classifies them as production, credit, consumption, and service, and are in turn regulated by their competent entities [4,5].

This is how the high level of importance of cooperatives is evidenced, which motivates a broad search for reasons that justify and allow us to understand how the cooperative system has created sources of work. These entities have dynamically preserved their stay within the economy. Since the central resource for an organization to function and be maintained is people, it is essential to know the behavior and contribution generated by human resources and whether it depends on their abilities, skills, and attitudes to guarantee stability, profitability, and productivity for an entity. Therefore, we proceed to investigate and analyze a case study of an entity under the cooperative profile called “Cooperative of Artisan Women TEJEMUJERES”, which has more than 25 years in the market. It is vital to analyze if the abilities, skills, and competencies possessed by human resources are a crucial factor in the preservation of the cooperative system. Therefore, the application of the “Work with the People” (WWP) model will be supported, which is an approach and evaluation system of current projects under a social development plan based on teamwork and its need to connect acquired knowledge and actions. In addition to the technical value that is guaranteed in the production of goods and services, this also values the person who executes it in order to constitute a practical model because this is aligned with the objectives that cooperatives want to meet. Therefore, the topic focuses on solving the following question: How do competencies contribute to the development of the cooperative system?

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Cooperativism and Local/Rural Development

The new millennium identifies cooperativism as a response to a series of challenges such as: loss of the sense of subsidiary work; weak cooperativism in financial and agricultural aspects; diversification that demands procedures and high technification that require investments for tools, machinery, and other resources; deficient educational and preparation processes; finally, the migration of people to urban spaces as a result of the lack of sources of income or jobs in rural areas, which is the most common situation that occurs. For these reasons, the cooperative model is consolidated as an effective mechanism for equitable development among the people who make up a society, which motivates social and economic growth. This model was born as a result of the industrial revolution in the interest of giving decent work to workers by providing a better quality of life through agreements between employers and workers that guarantee an environment of equal collaboration [6,7]. Since then, a profile of cooperativism has started where equal treatment was first sought, but little by little the need and uncertainty of having a job motivated the integration of societies or cooperatives under a productive, financial, consumption, and service scheme. As described in the latest report called World Cooperative Monitor carried out by the International Cooperative Alliance. The participation of cooperatives was defined according to the economic sector: 34% insurance; 32.7% agriculture and food industry and fishing; 18.3% wholesale and retail trade; 9.3% financial services; 3.3% industry and public utility services; 1.7% education, health, and social work; finally, 0.7% other services, including housing issues [8,9].

The strengthening of cooperativism lies in the close relationship that has existed between the level of development of organizations and the environment in which they operate, with social stratification being a relevant factor [10]. Therefore, the cooperative model tries to take advantage of its main advantage, which is to achieve a common good, in order to guarantee relief in the level of poverty through the generation of jobs and promote effective human, social, and cultural development [11]. Therefore, naturally, this type of model arises in rural areas where business intervention and public authorities are scarce and do not provide the necessary support mechanisms; conversely, real opportunities and managers are created and grow at the level of employment and product [12,13].

In this sense, cooperatives arise from a crisis or need based on economic, social, and cultural factors to: provide a greater capacity for the adaptation or optimization of human resources; promote the development of the capabilities, skills, and abilities of human resources; provide flexibility and adjustment of working conditions to promote the reduction of unemployment, flexibility, and adjustment within working conditions [14,15,16]. As an alternative to reducing unemployment, participation and direct interaction of workers in decision-making attributes by the company to its workers and thus strengthens effective business ties. In short, cooperatives are identified as an alternative system that promotes the socio-economic change of a group of people while contributing to the economic growth of the country, which guarantees compliance with the following principles: democratic and economic participation of partners; autonomy and independence; free, open, and voluntary membership; cooperation between cooperatives; concern for the community; the promotion of continuing education through training plans [17,18].

2.2. The “Working with People” Model and the IPMA Competencies as Skills Development Analysis Tools

For the application of the WWP model, it is assumed that collective action generates a flow of formal and informal knowledge that, when exchanged, allows for the creation of more sustainable and prosperous rural areas. Models are required that integrate the knowledge generated in social learning processes where practical action, experience, quality of social interaction, and communication are highlighted from decision structures and their relationships with agents by considering the input of external knowledge as a basic element for improving decision-making [19].

Therefore, the Working With People (WWP) model has been widely accepted since 2013 and, above all, has contributed to implementing responsible governance and rural development, rural prosperity and sustainability, and project-based governance in the context of social complexity in several studies carried out in Latin America, Spain, the US, and the rest of Europe; in this way, its validity at the international level has been evidenced, and is mainly focused on four fundamental principles [20].

The WWP model connects the knowledge and action of the team for a common project and values the their participants by promoting equitable participation, which in turn requires that the planners have a special social sensitivity, in addition to certain technical and contextual skills, as well as solid ethical standards. The WWP is presented as an alternative to the modern project and is the result of the research areas displayed in Figure 1 [20].

Figure 1.

Principles of the Working with People model. Source: Cazorla et al., 2013 [20].

In this area, the development of competencies arises because of the difference between the level of desired abilities and the one that an individual possesses, thus it is based on an evaluation for the diagnosis of the abilities defined or necessary to perform a particular function. This requires the application of strategies from a comprehensive, decentralized approach that in turn is aligned with the global tactics of the organization [21,22,23]. Likewise, the areas of knowledge must be perceived as the basis for the legitimization of the organization and, as previously mentioned, they must be perceived both individually and collectively [24].

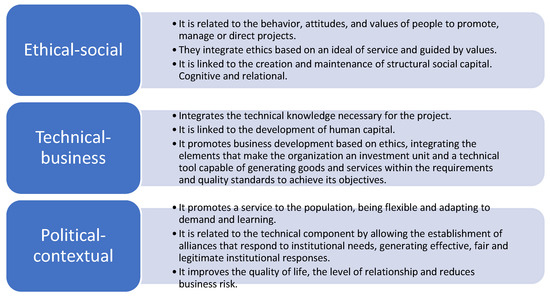

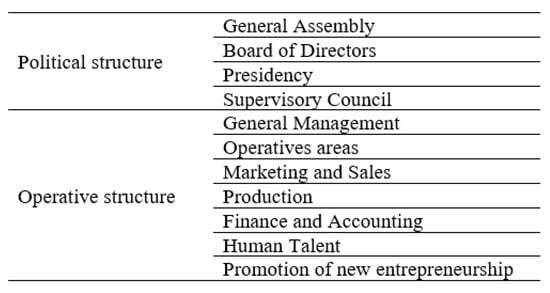

On the contrary, the International Project Management Association (IPMA) describes competence as a set of knowledge, personal attitudes, skills, and experiences necessary to be successful. Out of several competency models in the field of rural development projects. One with a holistic approach developed by the International Project Management Association was chosen because it broadens the concept of competency by integrating aspects such as behavior, skills, knowledge, motivation, strategy, and ethical issues. Which enables people to perform professionally and classifies the competencies in three dimensions that can be linked to the three components of the WWP as shown in Figure 2 [20].

Figure 2.

Components of the Working with People model. Source: Cazorla et al., 2013 [20].

Therefore, the WWP model, from the perspective of the social learning approach and the IPMA comprehensive competence model as shown in Figure 3, can be applied in rural development projects as a framework that focuses attention on the people involved and promotes their empowerment. Such as in the case of the Tejemujeres cooperative, which has implemented training plans in all areas since its creation so that the artisans can manage and lead the processes of the organization, whose line of business is framed within the principles of the popular and solidarity economy.

Figure 3.

Classification of competencies according to the IPMA and its link with the components of the Working with People model. Source: Cazorla et al. (2013) [20].

Based on the described context, the case study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis H1.

The cooperative, through training programs, has developed the necessary skills in the artisans to adequately articulate the organization’s social and business vision.

Hypothesis H2.

The cooperative represents an economic and social alternative for the artisans.

3. Methods

3.1. Case Study

3.1.1. Current Situation of the Gualaceo Canton

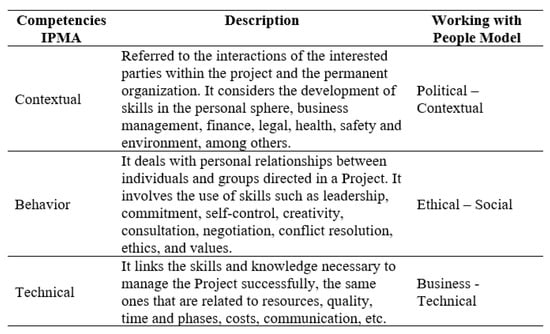

The Gualaceo canton is located in the northeastern area of the province of Azuay and has a total area of 346.5 km2 [25]. Its territory is made up of the Gualaceo urban parish— which, as the cantonal head, concentrates the largest number of inhabitants—as well as groups of eight rural parishes.

Like agriculture, craft activity in the Gualaceo canton has become one of the main pillars for the economy and the local development of its inhabitants, which makes it relevant to the World Crafts Council (WCC) through an event called the canton “Artisan City of the World” [26]. In addition, to guarantee the conservation of the cultural roots associated with this activity, in 2015, the National Institute of Cultural Heritage declared the Ikat technique an intangible heritage.

3.1.2. History and Constitution of the Tejemujeres Cooperative

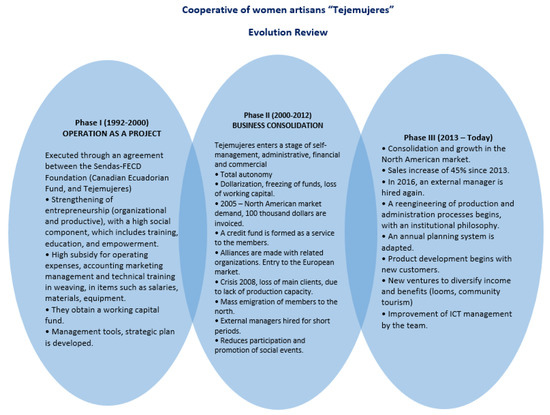

Tejemujeres emerged in 1992 in the Gualaceo canton as a rural development project promoted by the non-governmental organization SENDAS, which is established in the city of Cuenca in the province of Azuay as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Political division of the Gualaceo canton. Note: The graph shows the distribution of the different parishes (urban and rural) of the Gualaceo canton. Based on information from the Municipal Autonomous Decentralized Government of the Gualaceo canton [25].

The migratory crisis registered due to the so-called Bank holiday caused the cooperative to lose a significant number of associates due to migration [27]. The most outstanding milestones in the history and constitution of the Tejemujeres Craft Production Cooperative have been categorized into three phases:

3.1.3. Institutional Achievements in the Tejemujeres Timeline

Tejemujeres is the result of a social organization initiative of a group of artisan women from the rural area of the Gualaceo canton. Since 1992, have come together with the support of community leaders and public and private institutions with influence in the area to improve the living conditions of knitting artisan women in order to reach local and international markets directly with their fabrics so that the work is properly valued [28].

Since its creation, they have prioritized training programs in two axes: the first axis was based on weaving techniques, which allowed for artisans to meet the standards and demands of local and international clients; the second axis started from the organizational, business, leadership, and rights management processes and promoted many women to important management roles in the cooperative and various local and regional institutions.

According to the review carried out on the compliance report of the document Strategic Plan of the Tejemujeres Crafts Cooperative 2016–2020, the association has gone through various situations that have led them to face negative scenarios, mainly related to the economic factors derived from financial, political, and social crises (period 2008) and, over the last year, related to the pandemic caused by COVID-19, which has limited commercial activities throughout the world and various productive sectors [28].

Administrative and accounting processes and accountability systems were implemented for the efficient and transparent management of resources and strictly complied with accounting, tax, and legal regulations.

From the organization, the creation of collective spaces at the cantonal level was promoted, which made it possible to make community work visible and promote the participation of the population in the planning of the Cantonal Gad; this led to the additional formation of social structures in the area.

Throughout the life of Tejemujeres, the artisans have also been trainers of new weavers and developed skills, training, and communication methodologies that have been positively valued.

The results are based on an organizational system that has institutionalized the participation of those affected in planning, budgeting, and integration events. Once the investigations and field visits have been carried out, it is based on the premise that cooperatives act as agents of economic and social development and that they generate some type of impact on people, for which the following research question is posed:

How does the development of skills in the artisans of the Tejemujeres Cooperative contribute to the organization and personal life?

Therefore, the social and economic purpose of the Tejemujeres cooperative is different from a typical business, and the research focuses on the management process and its impact on the weavers, which was analyzed from the conceptual components of the Working with People model and the dimensions of the holistic model developed by the International Project Management Association [29].

The research required the implementation of a mixed approach through which qualitative and quantitative information is addressed. In this context, findings obtained through bibliographic and documentary review are combined, as well as the correct location observation of the reality of the analysis. With the numerical data collected from a field study, an evaluation is made of the skills possessed by the women who constitute the Tejemujeres cooperative.

To direct the field study, a complexity questionnaire was used in which variables of a technical, contextual, and social nature were observed; a competency questionnaire was used to evaluate the dimensions of communication, conflicts and crises, creativity and innovation, leadership, negotiation, planning and organization, teamwork and appreciation of values, and ethics [20]. The results obtained from its application are related through a multivariate analysis. Conversely, the documentary research provided information regarding the artisan sector in the Gualaceo canton and the history of the Tejemujeres cooperative.

3.2. Application of the Questionnaire

For the case study, the interview and the application of the questionnaire were addressed in several visits to Gualaceo, and the characteristics of the women of the organization made it difficult to meeting them all to apply the test in a single interview.

Finally, it was applied to the 85 participants of the organization. Given the size of the universe, a census sample approach was applied. This method consists of a well-organized procedure of collecting, registering, and analyzing information about the members of the population, which is called a census, as an official and complete count of the universe in which every unit of the universe is included in the data collection.

The test was designed so that the participants assessed the level of mastery of the competence according to their self-perception and their knowledge of the different items. For the ease of the questionnaire, the only action they had to take was to circle the chosen value.

The questions were elaborated so that the interviewee’s answers concerning how much they agree with the statement were measured using a Likert-type scale, which is used in the social sciences to evaluate the perceptions and quantitative aspects of the agents and grant the most favorable attitude the highest score. The rating scale is built based on a series of elements that reflect a positive or negative attitude about a stimulus or reference.

In the same way, the basis that sustains the development and analysis of social projects is manifested in the structuring of direction and management of projects. This is evidenced in studies carried out in rural development communities where the feasibility of executing the WWP model stands out, which motivates the need for knowledge of the complexity factors when directing a project and its effect on the development of skills according to studies carried out by De los Ríos and Guillen Torres on the Complex Project Management Model and their application to the integrated management of the Lasesa irrigation community. Based on this model, the instrument will be based on three components—social, technical, and contextual—and focused on seven relevant elements of the development of competence broken down into 89 items [30].

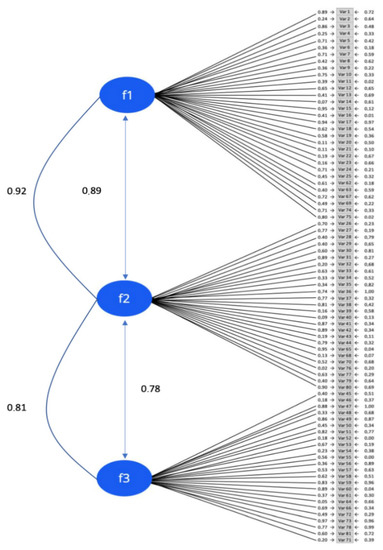

3.3. Questionnaire Validation

The verification of the validity of the content has been evaluated per the results obtained. The analysis of reliability and validity will allow for the determination of the degree of efficacy of the instrument [31]. For the validity, an analysis of factors will be applied; according to the derivations of the parameters, the dimensions that form for the WWP model will be determined; because there are items that are outside of the specifications of the parameters, it is assumed that the instrument is multidimensional and that it is necessary to counteract the hypothesis that will be verified by utilizing the confirmatory factorial analysis. The feasibility analysis is opposed to the reliability analysis due to the previous premise, and it must be determined if the items of the questionnaire can explain the other dimensions.

Confirmatory factor analysis allows us to analyze the effectiveness of the instrument. The coefficients and four goodness-of-fit indices were calculated. Finally, a correlation matrix of the questionnaire was composed to observe the degree of independence between the dimensions. Therefore, for the validity of the instrument of the proposed model, the use the confirmatory factor analysis has been considered.

4. Results

4.1. Sample

The sample was incidental and was made up of 85 women from the Tejemujeres cooperative of artisans. The mean age of the participants was 41 years (SD = 5.76). Regarding the level of education, 55.6% of the participants indicated that they had completed high school studies, while 48.4% have basic level studies at most. Regarding the marital status of the respondents, 69% were married, 16% were single, 4% indicated that they maintain a de facto union, and 3% identified themselves as single mothers. Furthermore, 27% of the members of the cooperative reside in the canton, and the rest of the women are located in Daniel Córdova, Luis Cordero, and Mariano Moreno at 24%, 22%, and 7%, respectively. It is also shown that 30% of the women travel to reach the cooperative around 30 min, and less than 5% have to travel more than an hour. Finally, 55.7% of the participants in the study indicated that their main activity is agriculture, and only 30% dedicated their main activity to crafts.

The results obtained in the questionnaire for each of the dimensions and their competencies are detailed below and have made a group comparison through level of schooling, age range, and main economic activity.

4.2. Item Analysis

Documentary information collection instruments were used in the study. Through the survey, it was possible to carry out the content analysis in the information analysis stage; conversely, in the descriptive statistical report, the accumulated data for certain sections allowed for the application of some inferential statistical analysis.

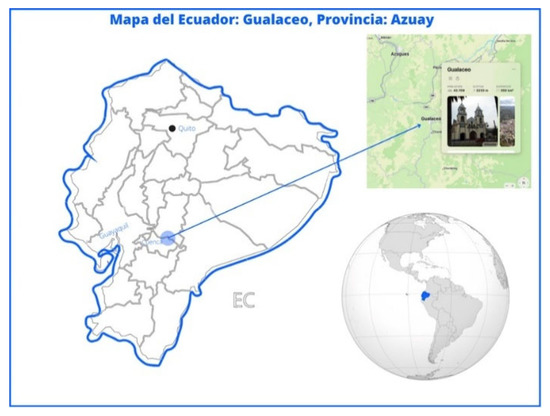

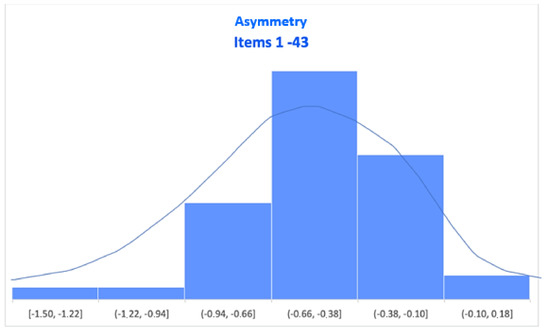

At first glance, it could be indicated that there is an asymmetry in the information— that is to say, that the sample is normally distributed (Figure 5)—which gives rise to the contrast in the results of the questionnaire and the trust that the dimensions are related to the competencies. However, it can be seen that there are items that do not correspond to the parameters because they are outside the established range <|1|, which may be because the item may not be sufficient or the dimensions of select items are too closely related and could be combined.

Figure 5.

Political and Operative Structure of the Tejemujeres Cooperative.

After analyzing the distribution of the data, it can be observed that the distribution is normal. The developed questionnaire seeks to measure the perceived value of competencies. For this section, SPSS statistics version 26 was used, while Stata and some Reviews checks were used for factorial analysis for the ease of calculating the factor loading and seeing them from a graphical perspective.

The analysis of the items corresponds to the pre-established dimensions according to the WWP model—Context, Social, and Technical—which determine the complexity of the project and the skills for project management.

4.3. Reliability

The reliability of the study has been verified by applying Cronbach’s alpha. Reliability directly related to the validity of the measure is the consistency of the results between items. Cronbach’s alpha indicates how closely certain elements are related as a set. It is considered a measure of scale reliability [32,33]. The values expressed for Cronbach’s alpha are acceptable and are detailed below as shown in the Table 1:

Table 1.

Reliability of complexity.

According to the results obtained in the Table 2, the artisans affirm that the cooperative has allowed them to develop their skills (with an average value of 3.06), which highlights the variables with the highest scores: “Teamwork” and “Communication”, respectively, and finally “Leadership”.

Table 2.

Reliability of the effects on the skill development of craftswomen.

Concerning the results obtained in Table 3, the Focus Group shows that the artisans relate the variable “Leadership” with the structural changes suffered in the management of the cooperative as a result of the recent losses generated, the departure of the partners, migration, prolonged administrative instability, the absence of new market opportunities, the decrease in income, and the increase in costs. On the contrary, the variable “Communication” is related to the development of ICT that involve internal and external customers. The variable “Teamwork” is articulated to the high level of training that they have.

Table 3.

Evaluation of the effects of the Tejemujeres cooperative on the development of artisan skills.

After the description, the load of the dimensions proposed by the WWP model is analyzed through the AFC to start with a relationship previously contrasted by the theory. In the model proposed for the measurements corresponding to the WWP, it is observed that the items are bidirectional and have a high load. The factors considered are: age, level of schooling, and main economic activity (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Review of the evolution of Tejemujeres.

Through an ANOVA analysis of differences in means, the evaluation of the importance that the Tejemujeres give to each of the dimensions proposed by the WWP model is observed. As shown in Table 4, the participants gave a high value to skills that involve the technical dimension with an average score of 5.71, followed by the contextual dimension with 5.01, and the social dimension is the least appreciated. It is important to observe that for the three dimensions of the model, statistical significance is met, which allows us to infer that in all dimensions of the WWP model, the competencies are relevant for the study groups that meet the characteristics of the Tejemujeres.

Table 4.

Sample analysis.

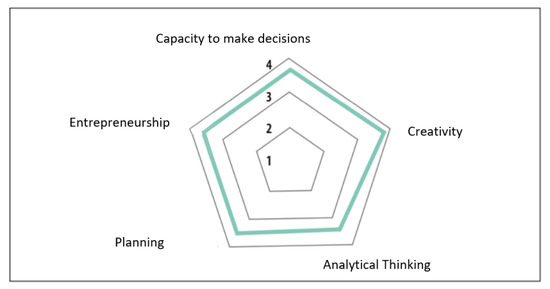

4.4. Political—Contextual Dimension

Regarding the scores reported by the artisans concerning the competencies associated with contextual politics, there is a high domain (M = 4.01; SD = 1.02).

The results of the study on the competencies of the political-contextual dimension indicated that the artisans gave a higher score to the ability to make decisions (M = 4.76; SD = 1.86), followed by creativity (M = 3.51; SD = 1.21), entrepreneurship (M = 3.37; SD = 1.61), planning (M = 3.24; SD = 1.21), and analytical thinking.

Next, a series of comparisons is presented, which considers age, level of schooling, and main economic activity as grouping factors (Figure 7 and Table 5).

Figure 7.

Information asymmetry.

Table 5.

Competences related by groups: Political-contextual Dimension.

4.5. Social Ethics Dimension

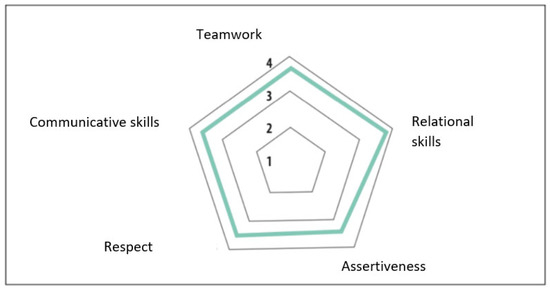

Regarding the scores reported by the artisans concerning the skills associated with social ethics, there is an intermediate domain (M = 3.31; SD = 1.59). The results of the study showed that regarding the competencies of the ethical-social dimension, the artisans gave a higher value to teamwork (M = 4.76; SD = 1.16) and relational skills (M = 4.71; SD = 1.21), followed by a high value for respect (M = 3.97; SD = 1.41), and finally assertiveness (M = 3.54; SD = 1.61). Next, a series of comparisons is presented, which considers age, level of schooling, and main economic activity as grouping factors (Figure 8 and Table 6).

Figure 8.

Item analysis.

Table 6.

Competences related by groups: Ethical-social dimension.

4.6. Technical-Business Dimension

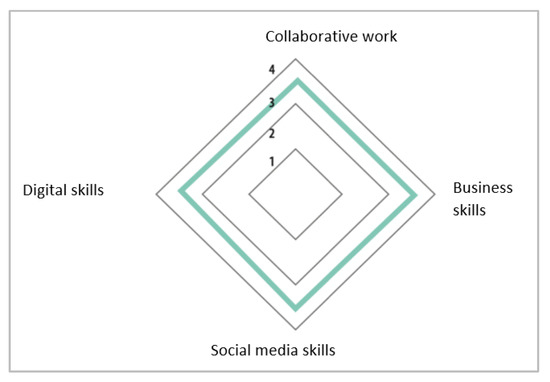

Concerning the scores reported by the artisans in the skills associated with the technical business dimension, a medium domain is evident (M = 3.31; SD = 1.59). When analyzing the results of the study, it is shown that the artisans gave a higher value to collaborative work (M = 3.96; SD = 1.82) and commercial skills (M = 4.11; SD = 1.81), followed by digital skills (M = 2.97; SD = 1.01), and finally skills in social networks (M = 1.45; SD = 1.01). Next, a series of comparisons is presented, which considers age, level of schooling, and main economic activity as grouping factors (Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 and Table 7).

Figure 9.

Political-contextual Dimension.

Figure 10.

Ethical-social dimension.

Figure 11.

Technical Dimension.

Table 7.

Competences related by groups—Technical dimension.

5. Discussion of Results

Indeed, it can be shown that motivation and the effective development of skills contribute to strengthening cooperative systems, which promotes the conservation of companies focused on common welfare—mainly regarding gender inclusion—which is supported by the alignment of the sustainable development goals. However, as in previous studies the relevance of including the CFS-RAI principles is identified to achieve the SDGs efficiently [34,35,36]. In addition, these principles are related to the model applied in this study since it has been identified that the WWP model has contributed to solving problems in rural areas according to their contexts, which allows for a better organizational system where the main objective is to promote entrepreneurship. In addition, as part of its recommendations, it is to integrate said model in the analysis of sustainability cases and thus guarantee an effective design of rural sustainable development models.

According to the scheme that is managed in Tejemujeres, the practical application of principle 3 of CFS-RAI is supported, in which the main objective is to promote gender equality and the empowerment of women. In a study highlighted by GESPLAN and the Salesian Polytechnic University, a cooperative that has a similar structure to the organization of producers of vegetables in Azuay known as Cooperative Prograserviv agrees that among their achievements is the integration of female partners and board members; in turn, they agree with the low level of contribution of leadership competence, which is commonly witnessed by administrative problems. In addition, the interest of the academic community focuses on promoting studies in rural development guided by sustainability and thus promoting the management of physical, human, economic, and financial resources.

6. Conclusions

Currently, the organization and constitution of cooperatives is a key factor to contribute to the economy of a country because it allows for a reduction of factors such as poverty, employment, and informal business, as stated by CICOPA, an organization that gives an exhaustive analysis of these entities in order to know their level of participation on both national and international scales.

The research from the ANOVA analysis allowed us to characterize the turn of the business of Tejemujeres from the international parameters for an adequate direction of projects. These projects are guided by technical criteria to promote interest so that members can acquire solid knowledge related to their activities of work without neglecting the importance of contextual aspects such as motivation, decision-making power, and the determination to progress—which are based on values—and their ability to interact and relate to others.

From this perspective, the competencies that stand out the most in the technical dimension are commercial skills and collaborative work, which show that people between 36 and 50 years of age are dedicated to crafts, and that various economic activities under an average level of education are more accurately reflected. In addition, it can be shown that, within the political-contextual framework, the competence that stands out the most is the ability to make decisions. However, if it is evaluated based on the range parameter, in regard to the age factor, people between 36 and 50 years old dedicated to handicrafts maintain more solid and well-established competence despite their basic level of studies.

Likewise, within the ethical-social framework, teamwork stands out as a primary competence; however, under analysis by age factor, economic activity, and level of schooling, it is identified that a high level of self-esteem is preserved in women of 24 to 35 years of age from various areas with basic levels of study.

Once the results have been exposed, the question that encompasses this research can be answered by demonstrating that competencies are vital in an organization since they directly affect the achievement of institutional objectives and can allow them to adapt to the context in which they operate. Their development is not always easy to build or measure because they depend on several factors that are related to the characteristics of their members [1]. On the contrary, the WWP model makes it possible to put the situation the organization is going through into context and captures the perception and incidence of the organization in the lives of women who feel identified and proud of their achievements at an institutional and personal level. The situation supports this cooperative system and guarantees a very dynamic, collaborative working environment that motivates personal and professional interest and, above all, promotes common well-being.

As indicated by Ávila, Schmal, Rivero, and Vidal it is vital to have a strategic direction and organizational culture that allow for the establishment of tools and strategies that promote greater development in the cooperative system [37,38]. This is especially relevant to the skills management process based on the development of a skills manual in which management processes are attributed by competencies in such a way that it operationalizes the behaviors and conducts. This in itself will benefit the organization to have a clear and precise objective towards the common good and focus on results. As evidenced in the dimensions of the WWP model, contextual skills have been fundamental and very well-developed within the Tejemujeres cooperative and are reflected in its 30 years of institutional life. Which has allowed them to properly manage relationship systems with their strategic allies, leaders, and co-workers—especially at home—by promoting values and making weaving an activity to break with the social paradigms of the area, as well as integrating family members in the embroidery activity [28].

According to Melgarejo, competencies are based on the interest of the person and the opportunities obtained by having experience [39]. Therefore, just as Tejemujeres promotes a mechanism based on the development of competencies, some studies confirm the importance of maintaining and nurturing competencies in its members [40]. Once again, it is affirmed how valuable creativity, teamwork, and cooperativism are to lead an entity that is highly competitive since it builds loyalty among internal customers and considers them as partners and owners of the company. In this way, the objectives of the company, owners, collaborators, and employees are always aligned.

From the results of the investigation, a response is given to the proposed hypotheses. The training programs that have been implemented with the women of the cooperative have allowed them to develop skills as artisans. However, there is evidence of a lack of training in the areas that are required to be able to carry out adequate management of the projects, which is reflected in the fact that the cooperative fails to adequately articulate the social and business vision of the organization.

There is no doubt that the organization is made up of women and leaders committed to institutional objectives, which is why it represents a space for personal and organizational growth. However, within the economic aspect, it does not represent an alternative that generates necessary income for the artisans and it allows for more hours to be dedicated to the elaboration of fabrics and fewer working hours to be dedicated to the activities of indigenous women in rural areas of the canton (such as agriculture, raising small animals, homemaking). The situation is of significant concern since it directly influences the new generations because they do not consider Tejemujeres as an economic alternative and prefer to be linked to other work activities.

In contrast, the organizational capacity at a personal and group level to achieve the fulfillment of objectives in the short, medium, and long term requires the commitment, values, and skills of those involved. Therefore, it reflects the competencies demonstrated by the leaders and artisans and their commitment within the framework of the functioning of the cooperative system from the social dimension, which revolves around the weaving activity. Over the years, weaving has been losing space due to factors related to the economic situation, level of study, homework, etc.

Despite its long history and experience in the sector of making artisan fabrics, the cooperative prioritizes its social production system, which is characterized by adapting to the socio-economic conditions of the artisans. It makes use of computerized tools, promotes systems of participation and accountability, and constantly innovate processes, but has not yet managed to achieve greater economic development; on the contrary, it has experienced a series of problems that have affected its performance, which is reflected in the situation. Although profits have been reported since 2017, these are minimal and dependency has been generated on a single buyer who acquires 95% of the production; the remaining 5% is seldom placed in local markets due to competition from products from China, Bolivia, and Peru whose production costs and prices do not allow them to compete on equal footing. The model from the technical-business dimension contextualizes this problem. The skills necessary for project management have not been adequately internalized, and this situation is due to several factors that affect the lives of artisans.

Given this situation, questions arise that may be the subject of studies for this type of experience and are detailed below: Could it be determined that it is a successful project or not? Being a non-financial production cooperative, what vision should prevail? What or how should be the strategy so that human and social capital is on par with financial capital? These concerns are directed toward the recognition of the experience that has been recognized for 30 years at the local and international level, which could be extrapolated to other similar experiences for two-way learning that opens paths to more permanent solutions.

The Tejemujeres case study serves as a guide or business model for other cooperatives that seek the well-being and integration of their employees in the face of the diversity of internal activities that require the development of skills or abilities regardless of if they are technical, contextual, or social. In contrast, it puts the problems of these social processes in context and motivates other organizations, industries, small entrepreneurs, companies, or social businesses to promote products and processes with social responsibility that involve their members and the community in order to generate a positive impact on the local and national level and, subsequently, at the international level. According to what has been described, this research serves as a reference for projects related to personal, social, local, economic, business/productive development, sustainability, and ICT integration.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, M.O.; Writing—review & editing, I.D.l.R. and S.S.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Universidad Politécnica de Madrid for studies involving humans.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Uluate, J. Orientación laboral: Una revisión bibliográfica de su conceptualización y su aporte a la persona trabajadora ya las organizaciones laborales. Rev. Electrónica Educ. 2017, 21, 397–413. [Google Scholar]

- Eum, H.S. CICOPA. Second Global Report on “Cooperatives and Employment”. 2017. Available online: https://www.cicopa.coop/es/publications/second-global-report-on-cooperatives-and-employment/ (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- Kwan, B.; Frankish, J.; Quantz, D.; Flores, J. A Synthesis Paper on the Conceptualization and Measurement of Community Capacity; UBC Institute of Health Promotion Research, University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Calvopiña, A. Cooperativismo en el Ecuador. Eko 2019, 12. Available online: https://www.ekosnegocios.com/articulo/cooperativismo-en-ecuador (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- CEPAL. Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe. In Cooperativismo Latinoamericano: Antecedentes y Perspectivas; CEPAL: Santiago, Chile, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Luna González, A.; Guzmán Rodríguez, J. Diseño del Modelo de Competencias Para la Cooperativa Gestionando. Coop De La Ciudad De Pereira. Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira. 2011. Available online: https://repositorio.utp.edu.co/server/api/core/bitstreams/5714264d-e424-45de-bd74-844ad4374f8c/content (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Ramírez Figueroa, C.A. Cooperativismo y Competencias: De la Calificación al Auto Reconocimiento. Universidad Militar Nueva Granada. 2014. Available online: https://repository.unimilitar.edu.co/bitstream/handle/10654/12797/MONOGRAFIA.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 17 July 2022).

- Alianza Cooperativa Internacional (ACI). Exploring the Cooperative Economy. 2022. Available online: https://monitor.coop/sites/default/files/2022-01/WCM_2021_0.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Alianza Cooperativa Internacional (ACI). Exploring the Cooperative Economy, Report 2020. 2020. Available online: https://monitor.coop/sites/default/files/publication-files/wcm2020web-final-1083463041.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Chaskin, R.J. Building Community Capacity: A Definitional Framework and Case Studies from a Comprehensive Community Initiative. Urban Aff. Rev. 2001, 36, 291–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, M.; Robles, R. Viabilidad de la empresa cooperativa como una empresa humanista del siglo XXI. In Fomento del Cooperativismo como Alternativa Económica y Social Sostenible: Una visión de México y España; Arnáez Arce, V.M., Muciño, M.E., Eds.; Dykinson, S.L.: Madrid, Spain, 2018; pp. 15–32. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvfb6zt4 (accessed on 15 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Organización Internacional del Trabajo (OIT). Desarrollo Rural a Través del Trabajo Decente; Organización Internacional del Trabajo: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante, A. Gestión humana socialmente responsable en cooperativas de trabajo asociado colombianas. CIRIEC 2019, 5, 217–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.; Speers, M.; McLeroy, K.; Fawcett, S.; Kegler, M.; Parker, E.; Smith, S.R.; Sterling, T.D.; Wallerstein, N. Identifying and Defining the Dimensions of Community Capacity to Provide a Basis for Measurement. Health Educ. Behav. 1998, 25, 258–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laverack, G. An identification and interpretation of the organizational aspects of community empowerment. Community Dev. J. 2001, 36, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rábago, L.E. Gestión por Competencias: Un Enfoque Para Mejorar el Rendimiento Personal y Empresarial; Bussines Pocket; Netbiblo: La Coruña, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Egia, G. El modelo cooperativo: Mucho más que una alternativa ante la crisis. Dykinson 2018, 1, 33–67. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, B. La responsabilidad social empresarial: Una mirada desde el cooperativismo. Lupa Empresarial 2014, 1, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- García Bacuilima, J.L. Modelo de Aprendizaje Basado en Proyectos para el Desarrollo de Competencias de Contabilidad: Aplicación en la UPS. Ph.D. Thesis, E.T.S. de Ingeniería Agronómica, Alimentaria y de Biosistemas (UPM), Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla, A.; De Los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Salvo, M. Working with People (WWP) in rural development projects: A proposal from social learning. Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural 2013, 10, 131–157. [Google Scholar]

- Zambrano, J.; Moreira, D.; Machado, E. Estrategia para el desarrollo de la competencia profesional gestionar proyectos microempresariales. Retos Dir. 2021, 15, 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, P.; Hunter, G.; Carter, I.; Dowding, K.; Guala, F.; van Hees, M. The Development of Capability Indicators. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 2009, 10, 125–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusthaus, C.; Anderson, G.; Murphy, E. Institutional Assessment: A Framework for Strengthening Organizational Capacity for IDRC’s Research Partners; International Development Research Centre: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- García, S. Introducción a la economía de la empresa: Ediciones Díaz de Santos. 2020. Available online: https://www.editdiazdesantos.com/wwwdat/pdf/9788490522547.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- GAD Municipal del Cantón Gualaceo. Actualización del Plan de Desarrollo y Ordenamiento Territorial del Cantón Gualaceo. 2015. Available online: http://app.sni.gob.ec/sni-link/sni/PORTAL_SNI/data_sigad_plus/sigadplusdocumentofinal/0160000430001_PDYOT_GUALACEO_13-04-2016_12-58-36.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Ministerio de Turismo. Gualaceo es Designado como “Ciudad Artesanal del Mundo”. 2021. Available online: https://www.turismo.gob.ec/gualaceo-es-designado-como-ciudad-artesanal-del-mundo/ (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Naranjo, C. Experiencias Emergentes de la Economía Social, OIBESCOOP. 2020. Available online: http://www.oibescoop.org/wp-content/uploads/cap-15.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Tejemujeres. Cooperativa Tejemujeres. 2021. Available online: https://demo.tejemujeres.com/ (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- IPMA. IPMA Competence Baseline v.3.1. National Competence Baseline v.3.1. Valencia: International Project Management Association (AEIPRO). 2009. Available online: https://www.aeipro.com/es/27-publicaciones/varios-libros/37-ncb-30-bases-para-la-competencia-en-direccion-de-proyectos5.html (accessed on 27 February 2022).

- De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Guillén-Torres, J.; Herrera-Reyes, A.T. Complexity in the management of rural development projects: Case of LASESA (Spain). Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural 2013, 10, 167–186. [Google Scholar]

- Sastre-Merino, S.; Negrillo, X.; y Hernández-Castellano, D. Sustainability of Rural Development Projects within the Working With People Model: Application to Aymara Women Communities in the Puno Region, Peru. Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural 2013, 10, 219–244. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Flores, O.; Lajo-Aurazo, Y.; Zevallos-Morales, A.; Rondán, P.L.; Lizaraso-Soto, F.; Jorquiera, T. Análisis psicométrico de un cuestionario para medir el ambiente educativo en una muestra de estudiantes de medicina en Perú. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública 2017, 34, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oviedo, H.C.; Campo-Arias, A. An Approach to the Use of Cronbach’s Alfa. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría 2005, 34, 572–580. [Google Scholar]

- Aliaga, R.J.; De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Howard, F.S.M.; Espinoza, S.C.; Cristóbal, A.H. Integration of the Principles of Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems CFS-RAI from the Local Action Groups: Towards a Model of Sustainable Rural Development in Jauja, Peru. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla, A.; De los Ríos, I.; Afonso, A. Inclusión de los principios IAR y las DVGT en el ámbito académico: Compromisos de docencia e investigación en 15 universidades latinoamericanas y españolas. Working Paper 2019-2. 2019. Available online: https://cdn.website-editor.net/4d8a6bab4a9f473d8b3d0f2137a227c6/files/uploaded/DOC.FAO.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- GESPLAN. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. Hacia los Principios IAR: Cuatro Estudios de Caso para su Aplicación. 2016. Available online: https://cdn.website-editor.net/4d8a6bab4a9f473d8b3d0f2137a227c6/files/uploaded/IAR1.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Ávila, C.A.; De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Fernández, M. Illicit crops substitution and rural prosperity in armed conflict areas: A conceptual proposal based on the working with people model in Colombia. Land Use Police 2018, 72, 201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Schmal, R.; Rivero, S.; Vidal, C. Fortalezas y debilidades de un programa para el desarrollo de competencias genéricas. Form. Univ. 2020, 13, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Melgarejo, M. Metodología Para Desarrollo de Competencias Comportamentales en Directivos de Cooperativas de Trabajo Asociado (Bogotá-Itagüí). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogota, Colombia, 2014. Available online: http://repositorio.unal.edu.co/bitstream/handle/unal/49515/52492844.2014.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Alberto, M.; Mora, A.; Vanhuynegem, P. El cooperativismo en América Latina; Organización Internacional del Trabajo: La Paz, Bolivia, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 1–405. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).