Investment Risk Analysis for Green and Sustainable Planning of Rural Family: A Case Study of Tibetan Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

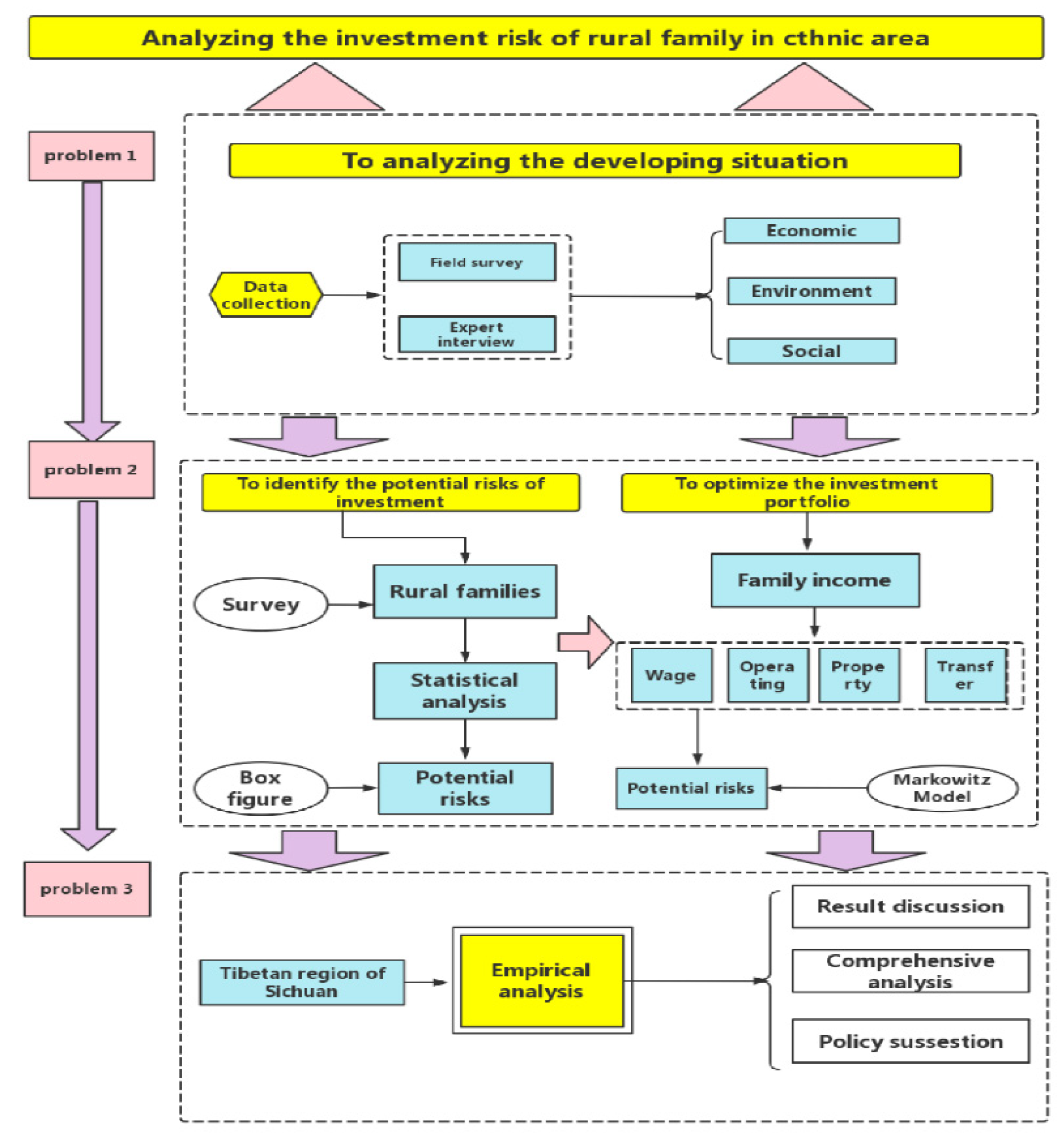

- To reveal the asset particularity of rural households in ethnic areas through statistical description and comparison;

- To identify the potential risks of investment in the special study area by illustrating with box figures and data analysis;

- To optimize the investment portfolio of rural households in ethnic regions utilizing the Markowitz model;

- To provide research evidence to promote the development Tibetan region of Sichuan by conducting an empirical study.

2. Literature Review and Research Framework

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Asset Composition of Household

2.1.2. Family Investment and Risk Avoidance

2.1.3. Family Investment in Rural Ethnic Areas

2.2. Research Framework

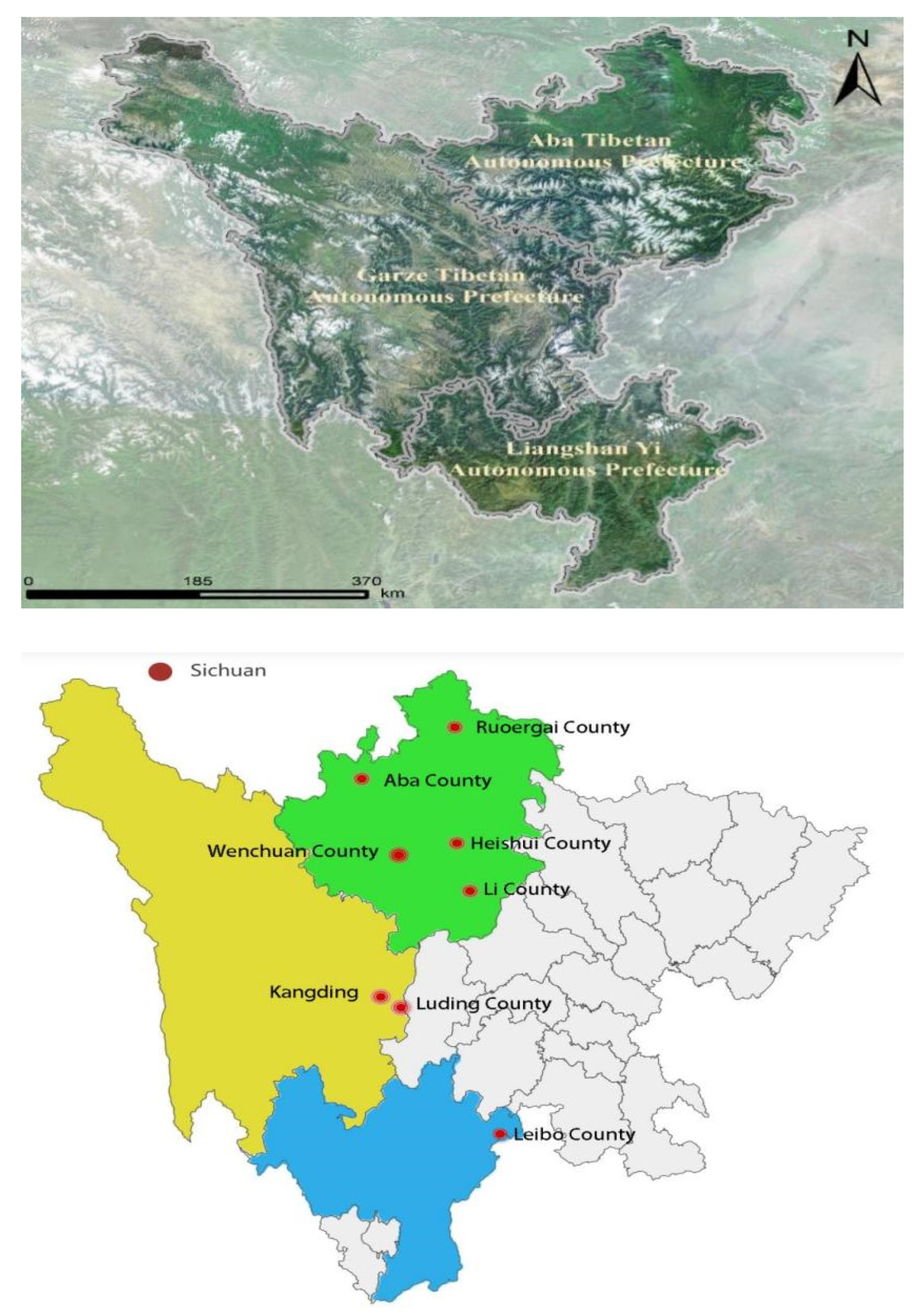

3. Study Area and Data

4. Methodology

4.1. Asset Analysis

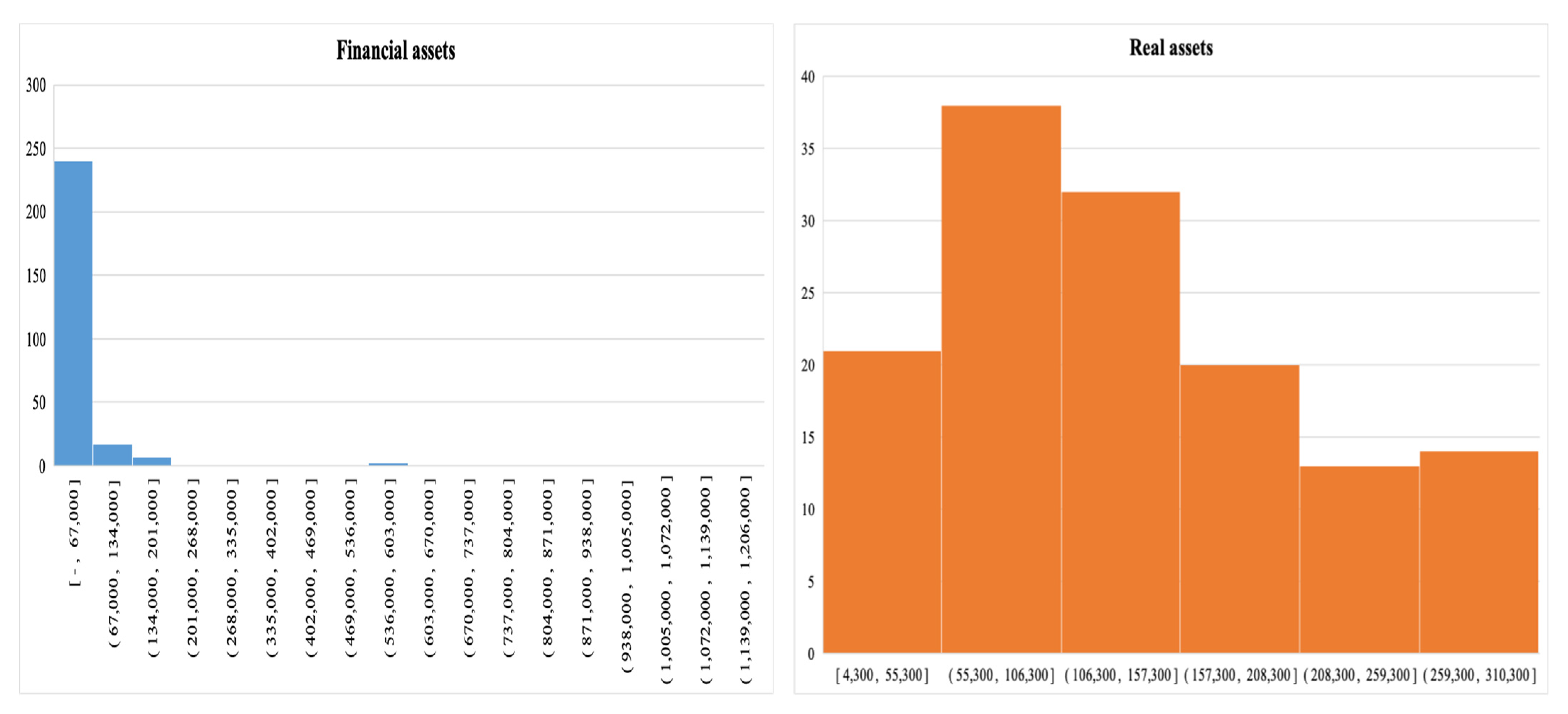

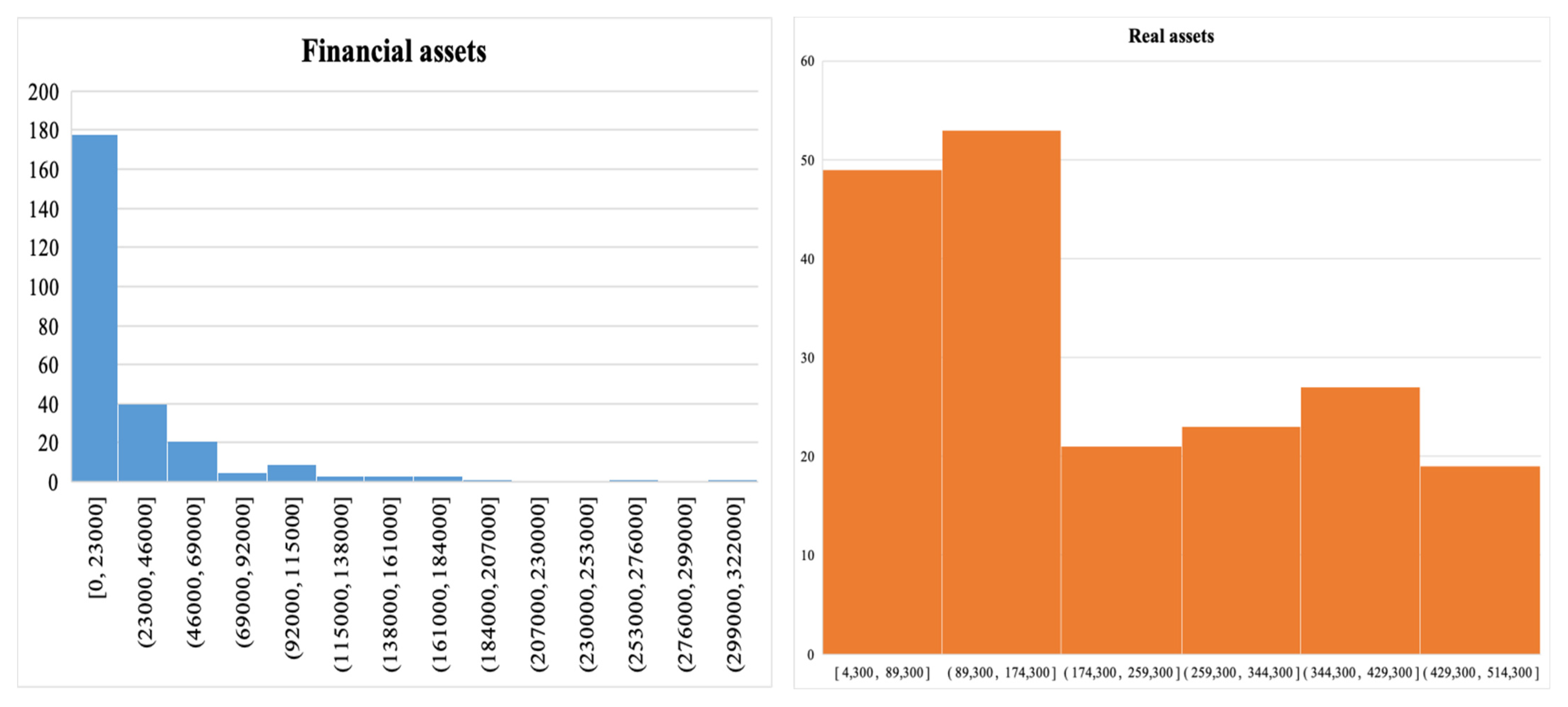

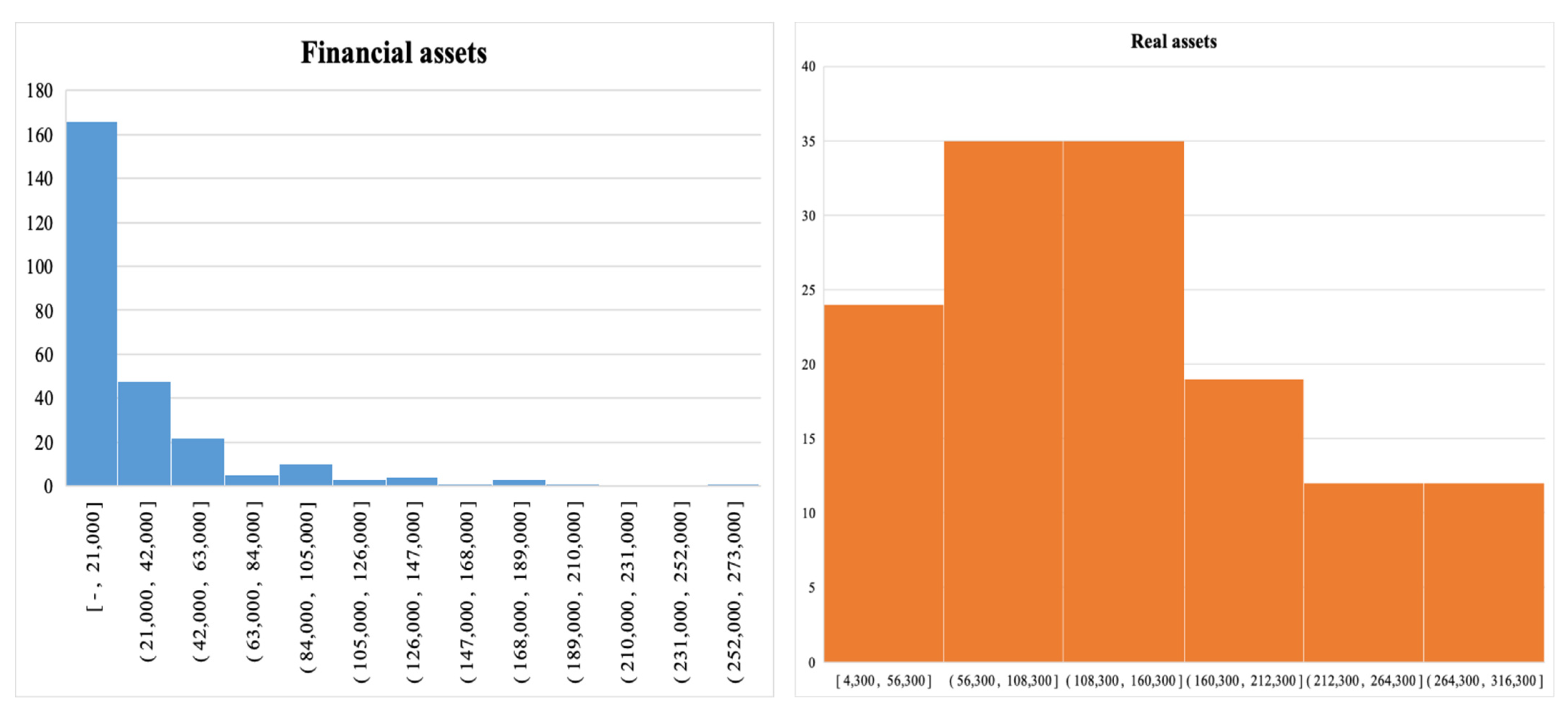

4.1.1. Statistical Description and Comparison

- Rural households have limited idle funds

- 2.

- Rural residents have low financial literacy and lack relevant financial knowledge

- 3.

- Rural residents have weak financial management awareness

- 4.

- Narrow information channels in rural of ethnic areas

- 5.

- The outlets and service coverage of financial institutions in ethnic areas is low

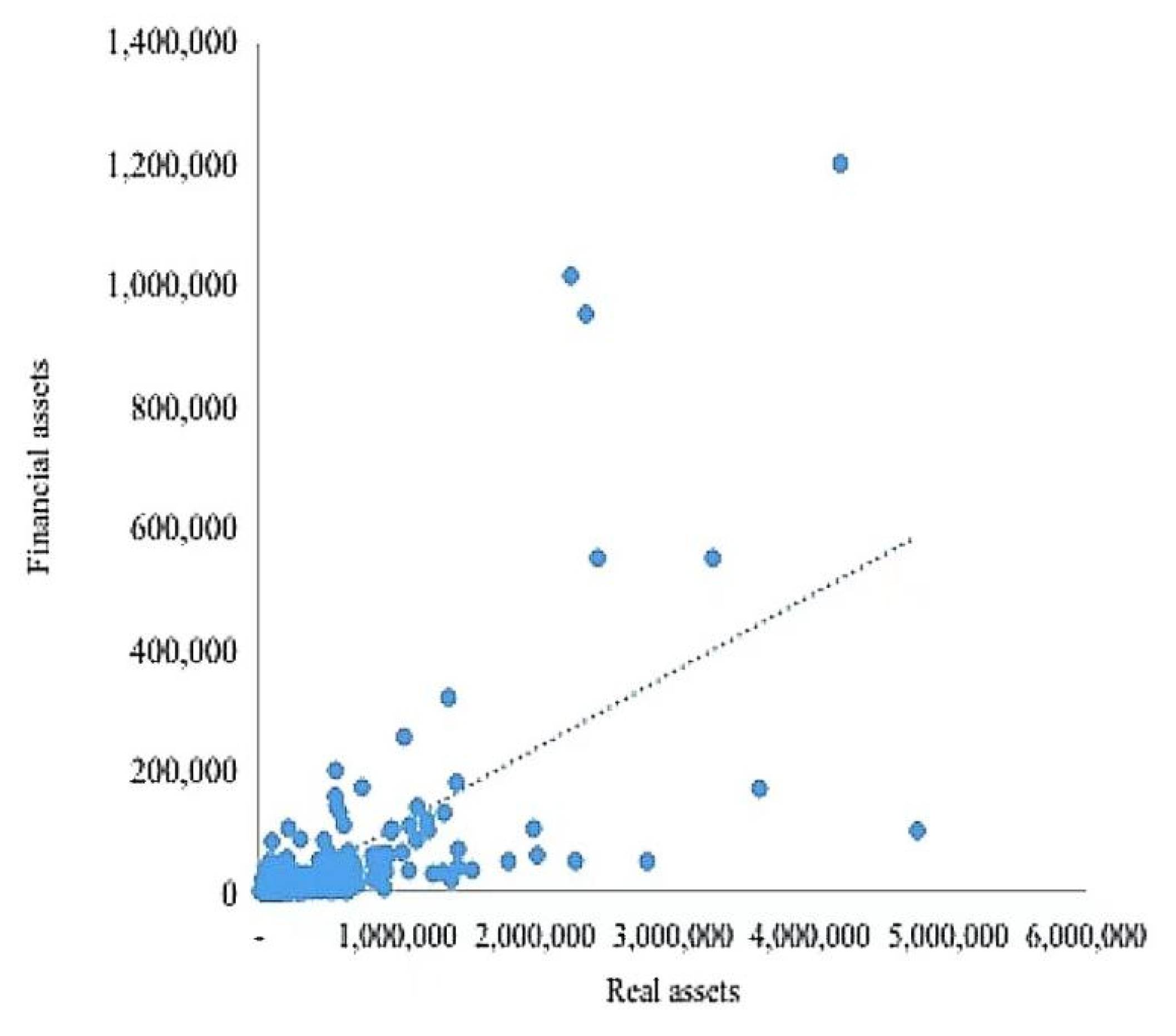

4.1.2. Risk Status

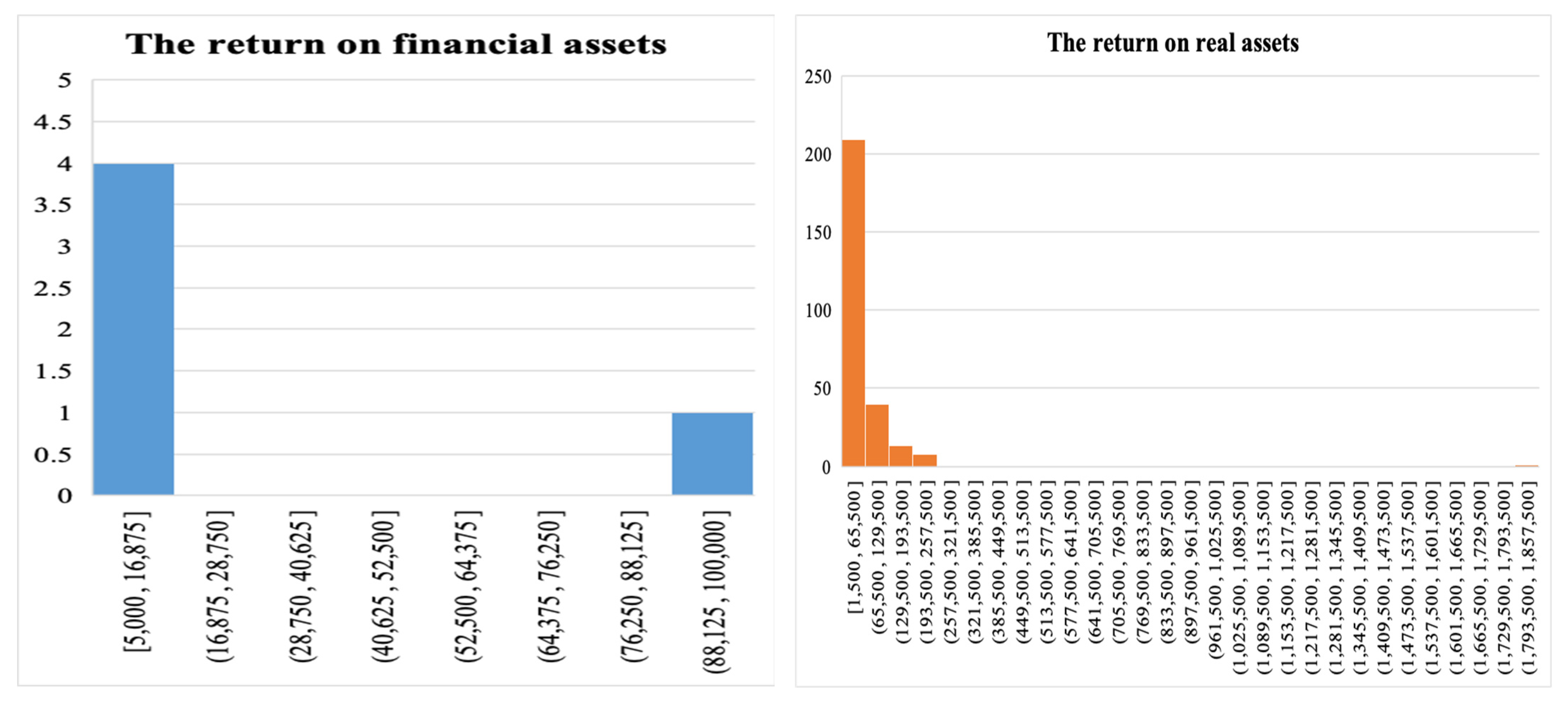

4.2. Investment Portfolio

4.2.1. Family Income

4.2.2. Optimization Model

5. Findings and Limitations

5.1. Findings

5.2. Limitations

6. Conclusion and Policy Implications

6.1. Concluding Remarks

6.2. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, L.; Chen, H.; Zou, C.; Liu, Y. The Impact of Farmland Transfer on Rural Households’ Income Structure in the Context of Household Differentiation: A Case Study of Heilongjiang Province, China. Land 2021, 10, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Huisingh, D.; Zhu, J.; Ma, Y.; O’Connor, D.; Hou, D. Farmers’ perceptions and adaptation behaviours concerning land degradation: A theoretical framework and a case-study in the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau of China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 2460–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Song, W. Spatiotemporal distribution and influencing factors of ecosystem vulnerability on Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Fan, C. Risk shock, rural household assets and persistent poverty: An empirical analysis based on CHNS microdata. Agric. Technol. Econ. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L. Rural financial ecological environment in Ningxia: Challenges and optimization paths. Ningxia Soc. Sci. 2021, 6, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, L. The impact of farmland property rights security on the farmland investment in rural China. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.; Yu, L.; Fan, G.-Z.; Zhang, D. Corporate fraud, risk avoidance, and housing investment in China. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2019, 39, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; He, Z. Housing demolition and financial market investment: Evidence from Chinese household data. Appl. Econ. 2022, 54, 4213–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Li, R.; Bian, S.; Gan, C. Financial planning ability, risk perception and household portfolio choice. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2021, 57, 2153–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, H.G.; Li, G.; Rozelle, S. Hazards of expropriation: Tenure insecurity and investment in rural China. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 1420–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Wang, X.; Yuan, G. Digital finance and the efficiency of household investment portfolios. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2021, 58, 2895–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Shen, J.; Hogarth, N.J.; Chen, Q. Risk preferences significantly affect household investment in timber forestry: Empirical evidence from Fujian, China. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 125, 102421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zheng, H.; Wang, X.; Peng, W.; Ma, D.; Li, C. Classification of the relationship between household welfare and ecosystem reliance in the Miyun Reservoir Watershed, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Jin, Y. Household wealth in China. Chin. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 47, 203–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wei, Z.; Ding, S. Empirical analysis on the inequality and the reason of China residents’ property distribution. Econ. Res. J. 2005, 6, 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Xiong, P.; Huang, Z. The asset management industry in China: Its past performance and future prospects. J. Portf. Manag. 2015, 41, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hardin III, W.; Hu, M. Housing, wealth, income and consumption: China and homeownership heterogeneity. Real Estate Econ. 2020, 48, 373–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulliner, E.; Malys, N.; Maliene, V. Comparative analysis of MCDM methods for the assessment of sustainable housing affordability. Omega 2016, 59, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiso, L.; Jappelli, T.; Haliassos, M. Household Portfolios: An International Comparison. 2000. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=245805 (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Xu, D.; Ma, Z.; Deng, X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, K.; Zhou, W.; Yong, Z. Relationships between land management scale and livelihood strategy selection of rural households in China from the perspective of family life cycle. Land 2020, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palia, D.; Qi, Y.; Wu, Y. Heterogeneous background risks and portfolio choice: Evidence from micro-level data. J. Money Credit Bank. 2014, 46, 1687–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wu, W.; Zhou, G. Inequality of opportunity and household risky asset investment: Evidence from panel data in China. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 63, 101513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Geobey, S.; Weber, O.; Lin, H. The impact of green lending on credit risk in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Li, L.; Xiao, L. Review of research on credit risk management for rural credit cooperatives. J. Risk Anal. Crisis Response 2017, 7, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, H. The utility of wealth. J. Political Econ. 1952, 60, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Xiao, J.; Wu, Y. Financial literacy and household asset allocation: Evidence from micro-data in China. J. Consum. Aff. 2021, 55, 1464–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Q.; Wei, X. Financial literacy, household portfolio choice and investment return. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2020, 62, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Si, F. How does the composition of asset portfolios affect household consumption: Evidence from China based on micro data. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-S.; Min, D. Efficiency of well-diversified portfolios: Evidence from data envelopment analysis. Omega 2017, 73, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yan, J.; Hua, X.; Yang, L. Determinants of livelihood choice and implications for targeted poverty reduction policies: A case study in the YNL river region, Tibetan Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 101, 1055–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y. Spatio-temporal patterns of rural poverty in China and targeted poverty alleviation strategies. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 52, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.; Cai, T. Financial experience, Financial literacy and Household venture capital: An analysis based on the 2017 China Household Financial Survey (CHFS) data. J. Southeast Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 23, 79–88, 151. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, W. Financial Literacy, Portfolio Choice and Financial Well-Being. Soc. -Dicators Res. 2017, 132, 799–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, M.; Kuar, J. Financial literacy and management of personal finance: A review of recent literatures. Res. J. Financ. Account. 2015, 6, 92–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Han, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, X. Impact of homestead housing on the allocation of financial assets of Chinese rural households. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; He, X.; Kong, R. The impacts of financial literacy on farmers’ behavior of farmland transfer: An analysis based on the regulatory role of farmland certification. China Rural Econ. 2018, 8. Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20183354737 (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Bialowolski, P.; Cwynar, A.; Weziak-Bialowolska, D. Financial management, division of financial management power and financial literacy in the family context—Evidence from relationship partner dyads. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 38, 1373–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ye, X.; Wu, Q. An Investigation on the concept and Mode of regional financial management of ethnic Minorities—A case study of Yuexi County, Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province. China Collect. Econ. 2019, 2, 19–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Pan, S.L.; Li, M.; Dai, Y.; Dong, X. The citizen-led information practices of ICT4D in rural communities of China: A mixed-method study. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 56, 102248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, T.; Winkler, A. The challenge of rural financial inclusion–evidence from microfinance. Appl. Econ. 2018, 50, 1555–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Paudel, K.P. Impact of Credit Constraints from Formal Financial Institutions on Rural Resi-dents’ Health in China. Healthcare 2021, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Mechanism and difficulty analysis of financial literacy promoting household economic behavior. Economist 2022, 3, 71–73. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W. Research on the efficient allocation of rural financial resources in China under the background of rural revitalization. J. Soochow Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 43, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, S.; Chen, Y. Spatio-temporal change of urban–rural equalized development patterns in China and its driving factors. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, Q.; Xie, H. Influence of the farmer’s livelihood assets on livelihood strategies in the western mountainous area, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rural Socio-Economic Survey Division, National Bureau of Statistics. China Rural Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Benjamin, J.R.; Cornell, C.A. Probability, Statistics, and Decision for Civil Engineers; Courier Corporation: Chelmsford, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Born, B.; Pfeifer, J. Policy risk and the business cycle. J. Monet. Econ. 2014, 68, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasiuzzaman, S.; Rahman, H.S.W.H.A. Performance of gold-backed cryptocurrencies during the COVID-19 crisis. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 43, 101958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritschl, A.; Sarferaz, S.; Uebele, M. The US business cycle, 1867–2006: A dynamic factor approach. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2016, 98, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaibi, H.; Ftiti, Z. Credit risk determinants: Evidence from a cross-country study. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2015, 33, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catherine, S. Countercyclical labor income risk and portfolio choices over the life cycle. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2022, 35, 4016–4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Asset Composition | Rural Family of the Study Area | Family of Nationwide Area | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Value (¥) | Percentage (%) | Mean Value (¥) | Percentage (%) | |

| Real assets | 479,354 | 91.86 | 1,426,140 | 88.2 |

| Financial assets | 42,449 | 8.14 | 190,806 | 11.8 |

| Total assets | 521,803 | 100 | 1,617,000 | 100 |

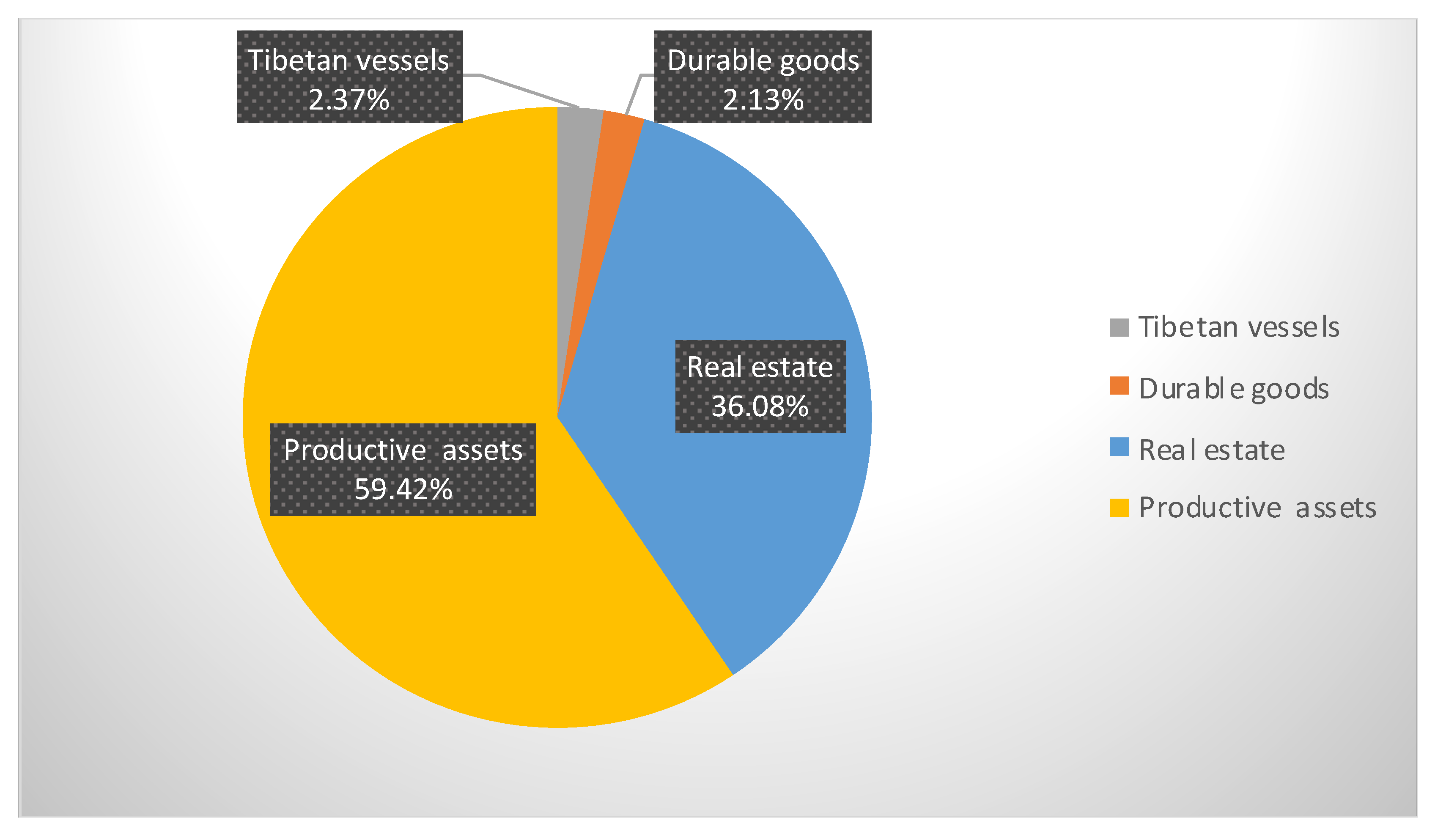

| Real Assets | Rural Family of the Study Area | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Value (¥) | Percentage (%) | |

| Real estate | 172,956 | 36.08 |

| Durable goods | 10,194 | 2.13 |

| Productive assets | 284,817 | 59.42 |

| Tibetan vessels | 11,387 | 2.37 |

| Real assets | 479,354 | 100 |

| Composition of Financial Assets | Rural Family of the Study Area | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Value (¥) | Percentage (%) | |

| Cash | 4344 | 10.23 |

| Bank deposits | 34,742 | 81.84 |

| Loans | 3234 | 7.62 |

| Others | 129 | 0.30 |

| Financial assets | 42,449 | 100 |

| Serial Number | X1 | X2 | Portfolio Returns | Portfolio Risk | Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.963 | 0.037 | 0.022 | 0.008 | 0.022–0.004 A |

| 2 | 0.856 | 0.144 | 0.049 | 0.011 | 0.049–0.005 A |

| 3 | 0.749 | 0.251 | 0.076 | 0.020 | 0.076–0.01 A |

| 4 | 0.642 | 0.358 | 0.103 | 0.035 | 0.103–0.0184 A |

| 5 | 0.535 | 0.465 | 0.129 | 0.057 | 0.129–0.028 A |

| 6 | 0.428 | 0.572 | 0.156 | 0.084 | 0.156–0.042 A |

| 7 | 0.321 | 0.679 | 0.183 | 0.118 | 0.183–0.059 A |

| 8 | 0.214 | 0.786 | 0.209 | 0.158 | 0.209–0.079 A |

| 9 | 0.107 | 0.893 | 0.236 | 0.203 | 0.236–0.102 A |

| 10 | 0 | 1 | 0.263 | 0.255 | 0.263–0.128 A |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Wen, Q.; Chandio, A.A.; Chen, L.; Gan, L. Investment Risk Analysis for Green and Sustainable Planning of Rural Family: A Case Study of Tibetan Region. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11822. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911822

Liu Y, Wen Q, Chandio AA, Chen L, Gan L. Investment Risk Analysis for Green and Sustainable Planning of Rural Family: A Case Study of Tibetan Region. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):11822. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911822

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yan, Quaner Wen, Abbas Ali Chandio, Long Chen, and Lu Gan. 2022. "Investment Risk Analysis for Green and Sustainable Planning of Rural Family: A Case Study of Tibetan Region" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 11822. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911822

APA StyleLiu, Y., Wen, Q., Chandio, A. A., Chen, L., & Gan, L. (2022). Investment Risk Analysis for Green and Sustainable Planning of Rural Family: A Case Study of Tibetan Region. Sustainability, 14(19), 11822. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911822