Conservation Proposals for Monasteries in Karpas Peninsula, Northern Cyprus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. State of the Art

3. Methodology of the Study

3.1. Literature Review

3.2. Archival Research

3.3. Site Survey

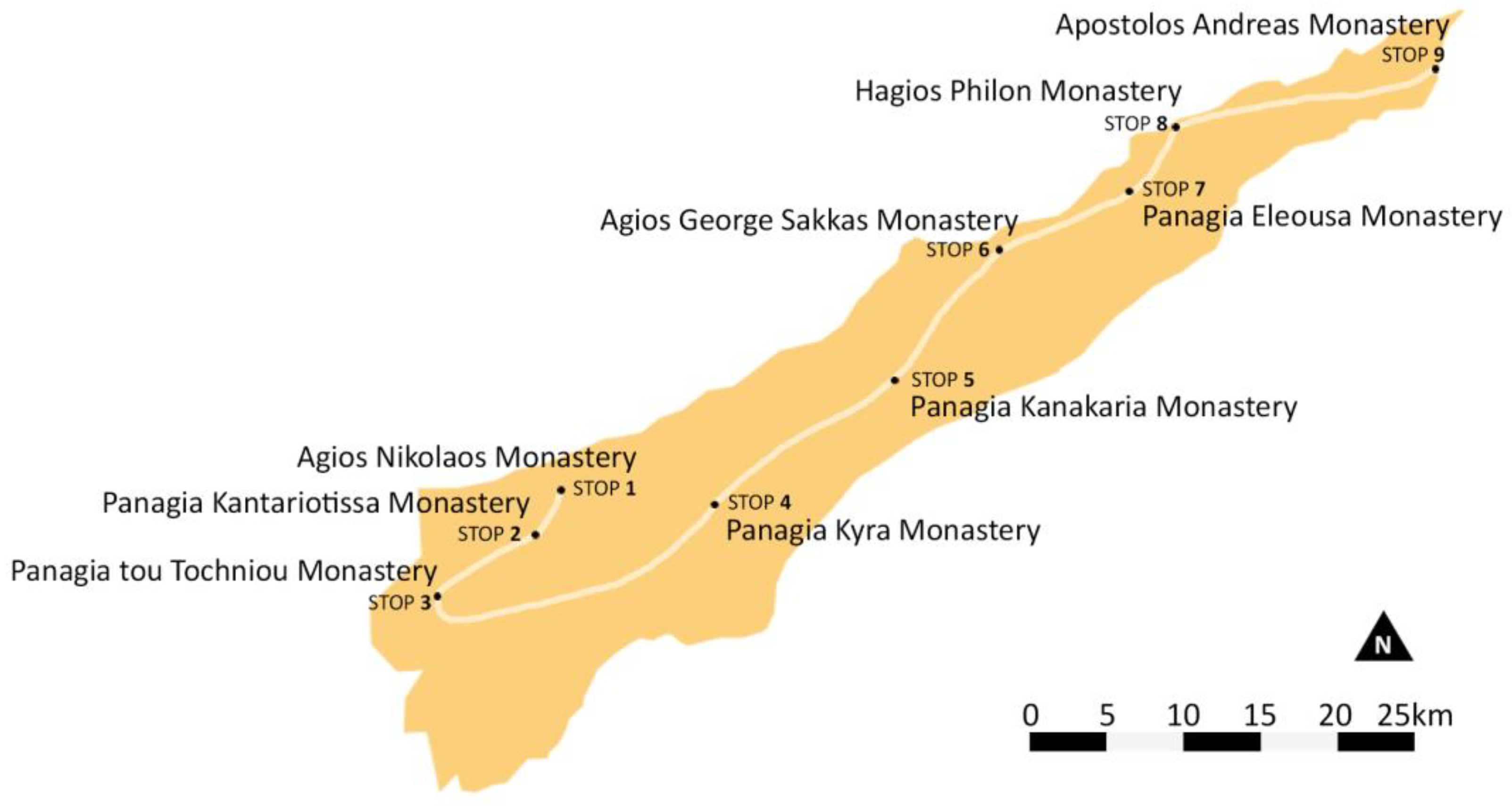

- Location Map: Identification of coordinates in order to prepare a location map;

- Inventory Forms: Preparing inventory forms with photographs, sketches, and notes about observations related with buildings (Table 1). This inventory form was prepared for the thesis of one of the authors and its scope is as in the thesis. The inventory form, the sample of which is given in Table 1, was created in order to collect the necessary information about the structures in a regulated manner while conducting a “site survey”. The prepared form consists of five main sections (identification of monasteries, ownership and use, architectural typology, building elements, structural damages), and in summary, it provides information on their locations, current usage situations, current environmental conditions, spatial characteristics, and the physical condition of the building elements;

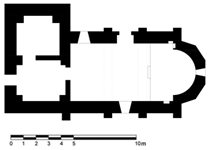

- Drawings: Investigated documents from the literature review that contains architectural drawings on parts of monasteries were redrawn and all other required measurements were conducted to obtain schematic representations of the plan layout and space characteristics for the monasteries. Drawings of the monasteries may contain few differences in measurements which were figured out during the process of integrating the drawing data of authors and other sources [38,42,50] about monasteries.

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Proposal

4. Case Studies-Monasteries in the Karpas Peninsula

4.1. Characteristics of the Karpas Peninsula

4.2. Monasteries in the Karpas Peninsula

4.3. Values of Monasteries

4.4. Site Survey and Analysis

4.4.1. Ownership and Legal Status

4.4.2. Environment, Setting and Access

4.4.3. Buildings

Plan Layout and Monastic Space Characteristics

4.4.4. Building Elements of Monasteries

Walls

Roof Structures

Doors, Windows, Shutters, and Lintels

Floor Surfaces

Furniture

4.5. Structural and Material Deterioration

4.5.1. Natural Reasons

4.5.2. Animal Attacks

4.5.3. Human Factors

Inappropriate Attitudes and Uses

Inappropriate Interventions

5. An Integrated Conservation Proposals

5.1. Restoration of Monasteries

5.2. Adaptive Reuse of Monasteries in the Karpas Peninsula through Monasteries Route

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bullen, P.A. Adaptive reuse and sustainability of commercial buildings. Facilities 2007, 25, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altınoluk, Ü. Binaların Yeniden Kullanımı, 1st ed.; YEM Yayınları: İstanbul, Turkey, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cantacuzino, S. New Uses for Old Buildings, 1st ed.; Architectural Press: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage Council Victoria. Adaptive Reuse of Industrial Heritage: Opportunities & Challenges; Heritage Council of Victoria: Melbourne, Australia, 2013.

- Highfield, D. Rehabilitation and Re-Use of Old Buildings; Spon Press: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ijla, A.; Broström, T. The sustainable viability of adaptive reuse of historic buildings: The experiences of two world heritage old cities; Bethlehem in Palestine and Visby in Sweden. Int. Invent. J. Arts Soc. Sci. 2015, 2, 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Vehbi, B.O.; Yüceer, H.; Hürol, Y. New uses for traditional buildings: The olive oil mills of the Karpas Peninsula, Cyprus. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2019, 10, 58–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, D. Creative Re-Use of Buildings 1–2; Donhead Publishing Ltd.: Shaftesbury, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bullen, P.A.; Love, P.E.D. Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings. Struct. Surv. 2011, 29, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayoub, B.; Yang, P.; Dayoub, A.; Omran, S.; Li, H. The role of cultural routes in sustainable tourism development: A case study of Syria’s spiritual route. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2020, 15, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. The Venice Charter: International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments, Venice, Italy, 25–31 May 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, Y.K. Adaptive Reuse of Abandoned Historic Churches: Building Type and Public Perception. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, T. Socio-Economic and Political Issues in the Successful Adaptive Reuse of Churches. Master’s Thesis, University of Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bullen, P.A.; Love, P.E. The rhetoric of adaptive reuse or reality of demolition: Views from the field. Cities 2010, 27, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J. Building Adaptation, 2nd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- De Arce, R.P. Urban Transformations and the Architecture of Additions, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Murialdo, F. Adaptive use and reuse: A time-specific process. In Conservation/Adaptation—Keeping Alive the Spirit of the Place. Adaptive Re-Use of Heritage with Symbolic Values, 2nd ed.; Fiorani, D., Kealy, L., Musso, S.F., Eds.; EAAE: Hasselt, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Šekularac, N.; Ivanović-Šekularac, J.; Petrovski, A.; Macut, N.; Radojević, M. Restoration of a Historic Building in order to Improve Energy Efficiency and Energy Saving-Case Study—The Dining Room within the Žica Monastery Property. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiorgio, V.; Uva, G.; Ruggieri, S.; Adam, J.M. Calibration of seismic vulnerability index for masonry churches based on AHP including architectural and artistic assets. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Recent Advances in Nonlinear Design, Resilience and Rehabilitation of Structures-CoRASS 2019, Coimbra, Portugal, 16–18 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Faro, A.; Miceli, A. New Life for Disused Religious Heritage: A Sustainable Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomans, T. Life Inside the Cloister: Understanding Monastic Architecture: Tradition, Reformation, Adaptive Reuse; Leuven University Press: Leuven, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lens, K.; Plevoets, B.; Van Cleempoel, K. Conservation of monasteries by adaptive reuse: The added value of typology and morphology. In Structural Studies, Repairs and Maintenance of Heritage Architecture XIII; Brebbia, C.A., Ed.; WIT Press: Ashurst Lodge-Southampton, UK, 2013; Volume 131, pp. 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, V. Sacred Architecture as Space of the Present Time. Recent Experiences in Conservation and Reuse of the Churches in the Historic Centre of Naples. In Conservation/Adaptation-Keeping Alive the Spirit of the Place. Adaptive Re-Use of Heritage with Symbolic Values, 2nd ed.; Fiorani, D., Kealy, L., Musso, S.F., Eds.; EAAE: Hasselt, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorani, D. Conservation and New Uses in Spaces of the Holy. In Conservation/Adaptation—Keeping Alive the Spirit of the Place. Adaptive Re-Use of Heritage with Symbolic Values, 2nd ed.; Fiorani, D., Kealy, L., Musso, S.F., Eds.; EAAE: Hasselt, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, J.P.; Sharma, J. The conservation of monasteries in the Western Himalayas. J. Archit. Conserv. 1997, 3, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulios, I. Living Sites: The Past in the Present—The Monastic site of Meteora, Greece: Towards a New Approach to Conservation. Ph.D. Thesis, University College London, London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Aulet, S.; Mundet, L.; Vidal, D. Monasteries and tourism: Interpreting sacred landscape through gastronomy. Braz. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 11, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liberato, P.; Gomes, M.; Liberato, D. Enhancing historical heritage and religious tourism in the North of Portugal: The monasteries route. In Advances in Tourism, Technology and Systems; Abreu, A., Liberato, D., Ojeda, J.C.G., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. The ICOMOS Charter on Cultural Routes. In Proceedings of the 16th General Assembly of ICOMOS, Quebec City, QC, Canada, 29 September–4 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Architects’ Council of Europe. Leeuwarden declaration—Adaptive re-use of the built heritage: Preserving and enhancing the values of our built heritage for future generations. In Proceedings of the Public Conference: Adaptive Re-Use and Transition of the Built Heritage, Leeuwarden, The Netherlands, 23 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Karataş, E. The Role of Cultural Route Planning in Cultural Heritage Conservation: The Case of Central Lycia. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Durusoy, E. From an Ancient Road to a Cultural Route: Conservation and Management of the Road Between Milas and Labraunda. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tamma, M.; Sartori, R. Religious heritage: Sharing and integrating values, fruition, resources, responsibilities. In Sapere l’Europa, Sapere d’Europa; Pinton, S., Zagato, L., Eds.; Università Ca’ Foscari: Venice, Italy, 2017; Volume 4, pp. 557–572. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnis, R. Historic Cyprus: A Guide to Its Towns and Villages, Monasteries and Castles, 1st ed.; Methuen Publishing: North Yorkshire, UK, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Enlart, C. Gothic art and the Renaissance in Cyprus, 1st ed.; Trigraph: London, UK, 1987. (In English) [Google Scholar]

- Grishin, A.D. A Pilgrim’s Account of Cyprus: Bars‘kyj’s Travels in Cyprus; Greece & Cyprus Research Center: Altamont, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Stylianou, A.; Stylianou, A.J. The Painted Churches of Cyprus-Treasures of Byzantine Art; J. G. Cassoulides & Son Ltd.: Nicosia, Cyprus, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorghiou, A. Christian Art in the Turkish-Occupied Part of Cyprus, 1st ed.; The Holy Archbishopric of Cyprus: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kaffenberger, T. Tradition and Identity: The Architecture of Greek Churches in Cyprus (14th to 16th Centuries); Reichert Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yapıcıoğlu, I. Basilicas, Cathedrals, Monasteries, Churches and Chapels in North Cyprus, 1st ed.; Ege University Press: İzmir, Turkey, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Papacostas, T.C. Byzantine Cyprus: The Testimony of Its Churches, 650–1200. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Batu, M.S. Kuzey Kıbrıs’taki Hagios Philon Manastırı. Master’s Thesis, Ege University, İzmir, Turkey, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Roudometof, V.; Michael, M.N. Economic Functions of Monasticism in Cyprus: The Case of the Kykkos Monastery. Religions 2010, 1, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Union of Cyprus Municipalities—Christian Monuments. Available online: https://ucm.org.cy/wp-content/uploads/destruction-2.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Aktina Tv Documentary—The Ancient Church of Agios Nikolaos. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e0onscAghCY (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Philokyprou, M.; Petropoulou, E. The impact of different philosophical approaches towards the conservation of ancient monasteries in Cyprus. In Structural Studies, Repairs and Maintenance of Heritage Architecture XII; Brebbia, C.A., Binda, L., Eds.; WIT Press: Ashurst Lodge-Southampton, UK, 2011; Volume 118, pp. 143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Philokyprou, M.; Petropoulou, E. Dealing with abandoned monuments: The case of historic monasteries in Cyprus. J. Archit. Conserv. 2014, 20, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mısırlısoy, D. A Holistic Model for Adaptive Re-use Strategies of Heritage Buildings. Ph.D. Thesis, Eastern Mediterranean University, Famagusta, Cyprus, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mısırlısoy, D.; Günçe, K. Questioning the Re-functioned Monastery Buildings in Northern Cyprus. In Conservation of Architectural Heritage (CAH), Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation; Versaci, A., Cennamo, C., Akagawa, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Cyprus—Drawings for the Apostolos Andreas Monastery Conservation works of the Chapel, the 1919 Building, Kitchen, Guesthouse and External Works. Available online: https://procurement-notices.undp.org/view_notice.cfm?notice_id=49005 (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Karpaz Area Local Development Strategy. Available online: http://www.tccruraldevelopment.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/local_development_strategy_karpaz_area.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2018).

- Harmansah, R. Appropriating Common Ground? On Apostolos Andreas Monastery in Karpas Peninsula. In The Northern Face of Cyprus: New Studies in Cypriot Archaeology and Art History; Summerer, L., Kaba, H., Eds.; Ege Yayınları: İstanbul, Turkey, 2016; pp. 477–488. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Cyprus—Restoration of the Monastery of Apostolos Andreas. Available online: https://www.undp.org/cyprus/projects/restoration-monastery-apostolos-andreas (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Yıldız, N. The Vakf Institution in Ottoman Cyprus. In Ottoman Cyprus: A Collection of Studies on History and Culture; Michael, M.N., Kappler, M., Gavriel, E., Eds.; Harrassowitz Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009; pp. 117–159. [Google Scholar]

- Yüceer, H.; Oktay Vehbi, B.; Hürol, Y. The conservation of traditional olive oil mills in Cyprus. J. Archit. Conserv. 2018, 24, 105–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS-ISCS—Glossary of Stone Deterioration. Available online: https://iscs.icomos.org/glossary-of-stone-deterioration/ (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Amato, A.; Andreoli, M.; Rovai, M. Adaptive Reuse of a Historic Building by Introducing New Functions: A Scenario Evaluation Based on Participatory MCA Applied to a Former Carthusian Monastery in Tuscany, Italy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Map | Photo | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. IDENTIFICATION OF MONASTERIES | 4.BUILDING ELEMENTS | |

| Building Name | 4.1 Stone Wall | |

| City/Village/Coordinates | Thickness/Plaster | |

| Legal Status | Ashlar | |

| 2. OWNERSHIP AND USE | Rubble | |

| 2.1 Ownership | Yellow cut stone | |

| Private/ Evkaf F./ Dept. of Antiquities and Museums | 4.1.2 Stylistic use of Stone around openings | |

| 2.2 Current Use | Facades having Buttresses | |

| Abandon/Other (Please specify) | Presence of Arches/Ornaments | |

| 2.3 Community | 4.2 Door | |

| Religious Community | 4.2.1 Size | |

| 3. ARCHITECTURAL TYPOLOGY | Small/Medium/Large | |

| 3.1 SITE-CONTEXT | 4.2.2 Shape | |

| 3.1.1 Location | Arch/Rectangular | |

| Rural/Urban | 4.2.3 Lintels | |

| On the flat areas/Slopy areas (Seaside or not) | Timber/Rectangular Slab Stone/Small cut Stone Frame | |

| On the mountain with poor/picturesque view | 4.2.4 Physical Condition | |

| Close to Village/Far from Village/ In Village | Intact-Very Good/Good | |

| 3.1.2 Type of Access | Partially damaged/Entirely damaged (Ruin) | |

| Vehicle/Pedestrian Access | 4.3 Window | |

| Dirt/Asphalt Road-Easy/Difficult | 4.3.1 Size (please write dimensions) | |

| 3.2 PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS | Small/Medium/Large | |

| 3.2.1 Period of the Buildings | 4.3.2 Shape | |

| Ancient/Contemporary | Arch/Square/Rectangular/Circle | |

| 3.2.2 Physical Condition of Building | 4.3.3 Existence of Small Holes on the walls (Yes/No) | |

| Intact-Very Good/Good | 4.3.4 Lintels | |

| Partially Damaged/Entirely Damaged (Ruin) | Stone Lintel/Timber Lintel | |

| 3.2.3 Physical Dimensions | 4.3.5 Physical Condition | |

| Small/Large Single Space | Intact-Very Good/Good | |

| Small/Large Repeated Space | Partially damaged/Entirely damaged (Ruin) | |

| 3.2.4 Number of Stories | 4.3.6 Wooden Shutter | |

| Single/Single with Mezzanine/ Double/Multi. | Presence of Wooden Shutter | |

| 3.2.5 Façade Characteristics | 4.3.6.1 Physical C. of Wooden Shutter | |

| Symmetrical/Asymmetrical | Intact-Very Good/Good | |

| Limited/Large/Repeated Openings | Partially damaged/Entirely damaged (Ruin) | |

| 3.2.6 Construction Material | 4.4 Roof | |

| Stone/Brick/Timber/Concrete/Steel | 4.4.1 Type of Roof | |

| 3.2.7 Spatial Organization | Flat R./Pitched R./Eave R./Dome/Semi- Dome/Vault/Other (Please specify) | |

| Integrated space (with connection) | 4.4.1.1 Physical Condition of Roof | |

| Attached space (without connection) | Intact-Very Good/Good | |

| Spaces connect Common S. | Partially damaged/Entirely damaged (Ruin) | |

| 3.2.8 Formal Characteristics | 4.5 Floor Cover | |

| Shape of the Plan/Type of the Plan | Larger Yellow Stone Flags/Marble | |

| 3.2.9 Structural Elements (Please Specify) | Stone/rubble stones/Compacted Soil/Mosaic/Other (Please specify) | |

| 3.2.10 Physical C. of Structural Elements | 4.5.1 Physical Condition of Floor Cover | |

| Intact-Very Good/Good | Intact-Very Good/Good | |

| Partially damaged | Partially damaged/Entirely damaged (Ruin) | |

| Entirely damaged (Ruin) | 5. STRUCTURAL DAMAGES | |

| 3.2.11 Other Phys. Elements/Characteristics | 5.1 Material Deterioration | |

| Ornament/Mosaic/Figure on Wall/Furniture | Loss of Material as layers parallel to surface | |

| 3.2.12 Physical C. of Other Characteristics | Loss of Material as big particles broken from main material | |

| Intact-Very Good/Good | Lack of walls/roofs/plasters - Inadequate const. details | |

| Partially damaged/Entirely damaged (Ruin) | Due to being close to sea/ Due to being abandoned | |

| Notes | ||

| # | Monasteries | Village | Current Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agios Nikolaos Monastery | Kaplıca | Abandoned |

| 2 | Panagia Kantariotissa Monastery | Kantara | Abandoned |

| 3 | Panagia tou Tochniou Monastery | Ağıllar | Abandoned |

| 4 | Panagia Kyra Monastery | Sazlıköy | Abandoned |

| 5 | Panagia Kanakaria Monastery | Boltaşlı | Abandoned |

| 6 | Agios George Sakkas Monastery | Yenierenköy | Abandoned |

| 7 | Panagia Eleousa Monastery | Dipkarpaz | Abandoned |

| 8 | Hagios Philon Monastery | Dipkarpaz | Ruin |

| 9 | Apostolos Andreas Monastery | Dipkarpaz | Church |

| |||

| # Monasteries | Context | Locational Characteristics | Type of Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Agios Nikolaos Monastery | Rural | Mountain, Far to Village | Dirt Road, Difficult, Vehicular Access |

| 2. Panagia Kantariotissa Monastery | Rural | Mountain, Far to Village | Asphalt Road, Easy, Vehicular Access |

| 3. Panagia tou Tochniou Monastery | Rural | Mountain, Far to Village | Asphalt Road, Easy, Vehicular Access |

| 4. Panagia Kyra Monastery | Rural | Mountain, Close to Village | Dirt Road, Easy, Vehicular Access |

| 5. Panagia Kanakaria Monastery | Rural | Flat Topography, In Village | Asphalt Road, Easy, Vehicular Access |

| 6. Agios George Sakkas Monastery | Rural | Mountain, Far to Village | Dirt Road, Difficult, Vehicular Access |

| 7. Panagia Eleousa Monastery | Rural | Mountain, Far to Village | Asphalt Road, Easy, Vehicular Access |

| 8. Hagios Philon Monastery | Rural | Seaside, Far to Village | Asphalt Road, Easy, Vehicular Access |

| 9. Apostolos Andreas Monastery | Rural | Seaside, Far to Village | Asphalt Road, Easy, Vehicular Access |

| # | Photo | Schematic Plan Layout | Space Characteristics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

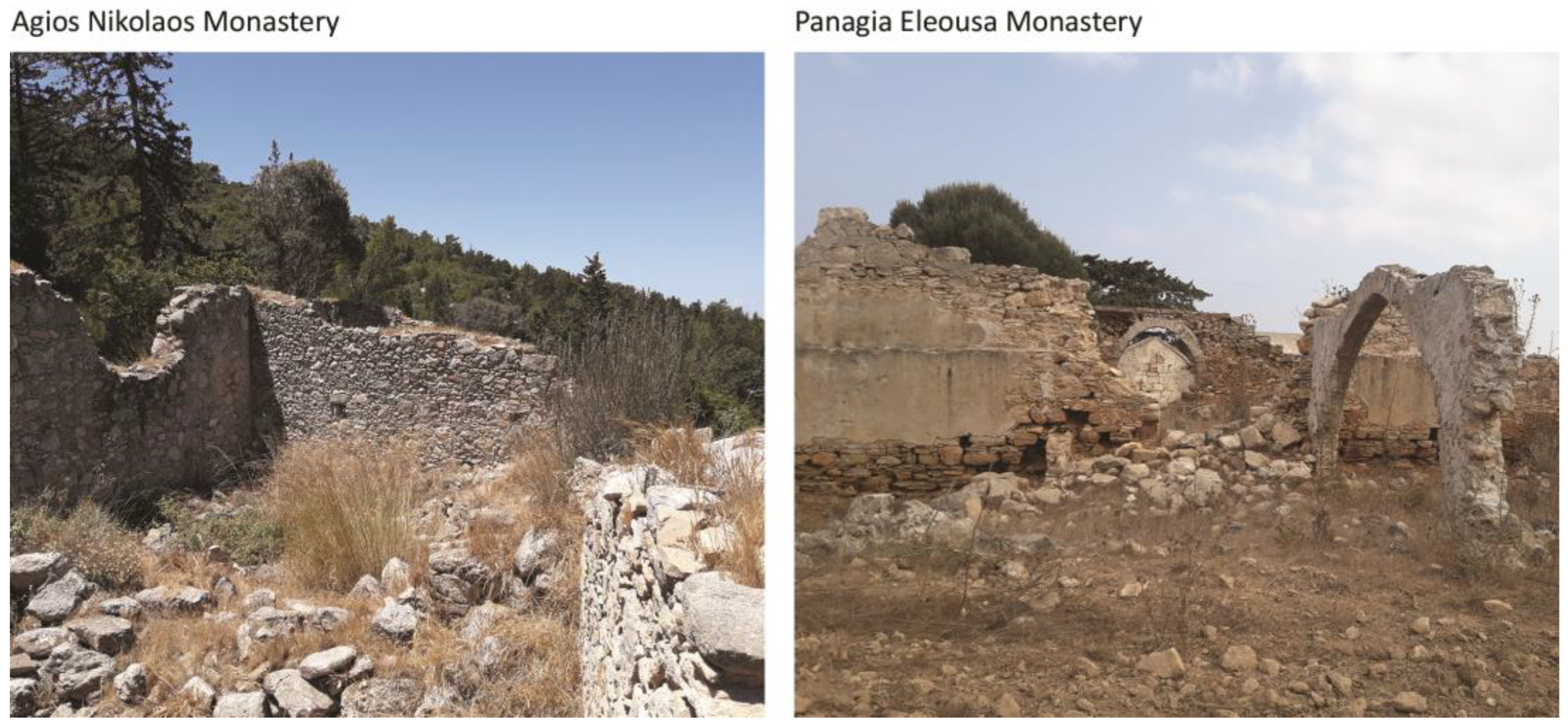

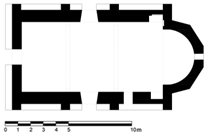

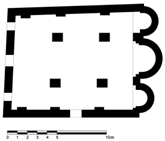

| 1. Agios Nikolaos Monastery |  |  | (a) | Single-nave church (approx. 7 m(9 m) × 16.5 m), Semi-circular apse, A division of narthex into two rooms, Single-story and rectangular form |

| 2. Panagia Kantariotissa Monastery |  |  | (b) | Single-nave church (approx. 9 m × 16 m), Semi-circular apse, Single-story and rectangular form, Two rectangular small rooms near to Church |

| 3. Panagia tou Tochniou Monastery |  |  | (c) | Dome-hall church (approx. 6.5 m × 11 m), Semi-circular apse, Single-story and rectangular form, Single-story building with covered walkway, consists of six small rooms, Cloister (partial) and ruins Surrounded by high walls |

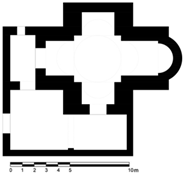

| 4. Panagia Kyra Monastery |  |  | (d) | Cruciform church (approx. 12.5 m × 15 m), Semi-circular apse, An additional semi-open space Single-story and square form |

| 5. Panagia Kanakaria Monastery |  |  | (e) | Basilica with aisles (approx. 16.5 m × 28 m), Semi-circular apses, Multi-story and Rectangular form, Two-story building consists of four small rooms at ground, and four small rooms at first floor, Surrounded by low walls Cloister (partial), and ruins |

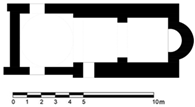

| 6. Agios George Sakkas Monastery |  |  | (f) | Single-nave church (approx. 5 m × 12.5 m) Semi-circular apse, Single-story and rectangular form |

| 7. Panagia Eleousa Monastery |  |  | (g) | Double-nave church (approx. 6 m × 11 m), Semi-circular apses, Common narthex, Single-story and rectangular form |

| 8. Hagios Philon Monastery |  |  | (h) | Cross in square church (approx. 11.5 m × 16.5 m) Semi-circular apses, Single-story and rectangular form Ruin |

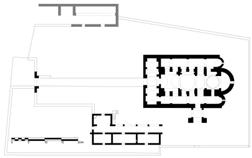

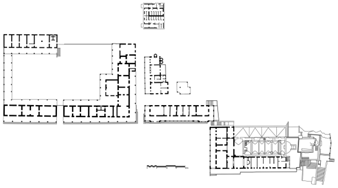

| 9. Apostolos Andreas Monastery |  |  | (i) | Single-nave church (approx. 11 m × 32 m) Semi-circular apse, Two-story and rectangular form Two-story building attached to Church Medieval church in square form Single story buildings with many multi-sized rooms Not surrounded by wall Cloister |

| Effect of External Factors | Damage to Stone | Damage to Timber |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Reasons | Discoloration Vegetation/mortar crumbling, cracks Existence of trees nearby building walls /cracks Weathering/demolition, cracks | Weathering/decay, fragile, broken |

| Animal Attacks | Erosion/on stone surfaces (pigeons) | Erosion/on timber surfaces (pigeons) |

| Human Factors | Inappropriate attitudes and uses: Graffiti on wall surfaces Neglect (no proper maintenance) Shooting activity of hunters damage walls Inappropriate interventions: Installing cement plaster on walls and Concrete covering on the floor plane (incompatible material) Installing electrical cables inside the walls Pipe installation on the walls | Inappropriate attitudes and uses: Removing doors, windows and shutters Neglect (no proper maintenance) Making fire damage on timber Inappropriate interventions: Closing of openings (windows) |

| # | Damage in Material and Structure (DMS) and Alterations with Wrong Decisions (AWD) | Restoration Proposals |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Agios Nikolaos Monastery | (DMS) Plant roots inside the wall and vegetation next to walls and site | Cleaning plants’ roots and vegetation with appropriate interventions and tools on walls and at site |

| (DMS) Loss of mortar (partial) | Replacement of mortar through injection method | |

| (DMS) Graffiti on walls | Removal of graffiti | |

| (DMS) Loss of and cracks on plaster | Replacement of the plaster with injection method | |

| (DMS) Big-sized holes and shot holes on stone | Addition of stones as similar to original material | |

| (DMS) Loss of windows and doors | Reproduction of timber frame windows and timber doors | |

| (DMS) Partially collapsed interior walls, collapsed walls and roofs | Partial reconstruction | |

| (DMS) Dampness and discoloration on stone | Eliminating the cause of damp and mechanical cleaning of stone | |

| (AWD) Concrete covering on the floor plane (partial) | Removal of incompatible concrete on floor, Replacement of floor covering with original material | |

| 2. Panagia Kantariotissa Monastery | (DMS) Loss of mortar (partial) | Replacement of mortar through injection method |

| (DMS) Broken and/or loss floor cover | Replacement of floor covering with original material | |

| (DMS) Cracks on stone arches and walls | Stitching of the masonry cracks and Injection grouting for cracks | |

| (DMS) Displaced keystone and stone | Replacement of the displaced keystone and stones | |

| (DMS) Graffiti on walls | Removal of graffiti | |

| (DMS) Loss and cracks on plaster | Replacement of the plaster with injection method | |

| (DMS) Dampness and discoloration on stone | Eliminating the cause of damp and mechanical cleaning of stone | |

| (DMS) Vegetation on wall, roof, and site | Cleaning vegetation with appropriate interventions and tools on walls, roofs, and at site | |

| (DMS) Loss of Tower’s bell | Replacement of bell as similar to original | |

| (DMS) Damaged wall and roof | Partial reconstruction | |

| (DMS) Damaged timber doors and windows | Repair/restoration of timber doors and windows | |

| (AWD) Using cement plaster in between some parts of stones | Removal of cement plaster and applying traditional plaster | |

| (AWD) Concrete covering on the floor plane (partial) | Removal of incompatible concrete on floor | |

| 3. Panagia tou Tochniou Monastery | (DMS) Vegetation on walls and site | Cleaning plants’ root and vegetation with appropriate interventions and tools on walls and at site |

| (DMS) Loss of mortar (partial) | Replacement of mortar through injection method | |

| (DMS) Broken and/or Lost stone floor cover at some parts | Replacement of floor covering with original material | |

| (DMS) Cracks on wall and arches | Stitching of the masonry cracks and injection grouting for cracks | |

| (DMS) Discoloration on stone | Mechanical cleaning of stone | |

| (DMS) Fire traces on walls and timber material | Cleaning to remove fire traces and replacement of timber material | |

| (DMS) Broken and/or Loss of doors, windows and shutters | Replacement and repair of damaged/lost doors, windows and shutters | |

| (DMS) Graffiti on doors | Removal of graffiti | |

| (DMS) Collapsed walls, roofs, and arches | Partial Reconstruction | |

| (AWD) Using cement plaster in between some parts of stones | Removal of cement plaster and applying traditional plaster | |

| 4. Panagia Kyra Monastery | Panagia Kyra Monastery is recently restored. | |

| 5. Panagia Kanakaria Monastery | (DMS) Loss of mortar (partial) | Replacement of mortar through injection method |

| (DMS) Dampness and discoloration on stone | Eliminating the cause of dampness, mechanical and chemical cleaning of stone | |

| (DMS) Vegetation on walls, stairs, and site | Cleaning vegetation with appropriate interventions and tools on walls, stairs, and site | |

| (DMS) Corrosion on stone stairs | Replacing new stone stairs as similar to original | |

| (DMS) Broken and/or loss of doors, windows, lintels and wooden shutters | Replacement and repair of the damaged and lost parts as similar to original design | |

| (DMS) Loss of and cracks on plasters | Replacement of the plaster with injection method | |

| (DMS) Corrosion of stone wall partially and cracks in walls | Stitching of the masonry cracks and injection grouting for cracks | |

| (DMS) Damage of wooden sheets | Repair/restoration of wooden sheets | |

| (DMS) Broken and/or lost stone floor cover at some parts | Replacement of floor cover with original material | |

| (DMS) Collapsed walls, roofs, and arches | Partial reconstruction | |

| (AWD) Electrical installations | Removal of incompatible electrical installations | |

| (AWD) Metal frame glass window and Window covered with plaster | Removal of incompatible materials (plaster, metal frame) and Replacing timber frame windows | |

| 6. Agios George Sakkas Monastery | (DMS) Dampness and discoloration on stone | Eliminating the cause of damp, and mechanical cleaning of stone |

| (DMS) Cracks on plasters | Replacement of the plaster with injection method | |

| (DMS) Damaged timber doors and windows | Repair/restoration of timber doors and windows | |

| (DMS) Vegetation at site | Cleaning vegetation with appropriate interventions and tools at site | |

| (AWD) Concrete covering on the floor plane | Removal of incompatible concrete on floor, Replacement of floor covering with original material | |

| 7. Panagia Eleousa Monastery | (DMS) Vegetation on wall surfaces and at site | Cleaning vegetation with appropriate interventions and tools on walls and at site |

| (DMS) Four big-sized and square holes at façade | Addition of stones as similar to original material | |

| (DMS) Loss of and/or cracks on Plaster | Injecting new traditional plaster at the lost parts | |

| (DMS) Loss of Mortar and Corrosion on stone walls | Replacement of mortar through injection method | |

| (DMS) Dampness and discoloration on stone | Eliminating the cause of damp and mechanical cleaning of stone | |

| (DMS) Lost, and/or Damaged doors, windows and shutters | Replacement and repair of the damaged, and/or lost parts | |

| (DMS) Collapsed walls, roofs, arches, and stairs | Partial Reconstruction | |

| (DMS) Cracks on stone walls | Stitching of the masonry cracks and Injection grouting for cracks | |

| 8. Hagios Philon Monastery | (DMS) Loss of Mortar and Corrosion on walls | Replacement of mortar through injection method |

| (DMS) Dampness and discoloration on stone | Eliminating the cause of damp and mechanical cleaning of stone | |

| (DMS) Vegetation on floor and site | Cleaning vegetation with appropriate interventions and tools on floor and at site | |

| 9. Apostolos Andreas Monastery | (DMS) Broken, Lost, and/or Damaged roof materials, doors, windows, shutters, stairs, and floor covers | Replacement and repair of the damaged, broken and/or lost parts |

| (DMS) Dampness and discoloration on stone | Eliminating the cause of damp and mechanical cleaning of stone | |

| (DMS) Loss and cracks on plaster | Replacement of the plaster with injection method | |

| (DMS) Vegetation at site | Cleaning vegetation with appropriate interventions and tools | |

| (DMS) Loss of Mortar and Corrosion on stone walls | Replacement of mortar through injection method | |

| (AWD) Incompatible new additions and mechanical, electrical, and pipe installations | Removal of incompatible addition and mechanical, electrical, and pipe installations that cause visual and noise pollution | |

| Monasteries | Context | Proposed New Functions for the Monasteries |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Agios Nikolaos Monastery | Leisure-Recreation Activities/Uses;

| Church Religious Activities/Uses |

| 2. Panagia Kantariotissa Monastery | Leisure-Recreation Activities/Uses;

| Church Religious Activities/Uses Monastery Buildings Educational Activities/Uses

|

| 3. Panagia tou Tochniou Monastery | Leisure-Recreation Activities/Uses;

| Church Religious Activities/Uses Monastery Buildings Educational Activities/Uses;

|

| 4. Panagia Kyra Monastery | Leisure-Recreation Activities/Uses;

| Church Religious Activities/Uses |

| 5. Panagia Kanakaria Monastery | Hospitality Activities/Uses

| Church Religious Activities/Uses Monastery Buildings Educational Activities/Uses;

|

| 6. Agios George Sakkas Monastery | Hospitality Activities/Uses;

| Church Religious Activities/Uses |

| 7. Panagia Eleousa Monastery | Educational Activities/Uses;

| Church Religious Activities/Uses |

| 8. Hagios Philon Monastery | Leisure-Recreation Activities/Uses;

| Ruin Hospitality Activities/Uses;

|

| 9. Apostolos Andreas Monastery | Leisure-Recreation Activities/Uses;

| Church Religious Activities/Uses Monastery Buildings Direct sale Activities/Uses;

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berkay, E.; Oktay Vehbi, B. Conservation Proposals for Monasteries in Karpas Peninsula, Northern Cyprus. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16070. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316070

Berkay E, Oktay Vehbi B. Conservation Proposals for Monasteries in Karpas Peninsula, Northern Cyprus. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):16070. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316070

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerkay, Erman, and Beser Oktay Vehbi. 2022. "Conservation Proposals for Monasteries in Karpas Peninsula, Northern Cyprus" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 16070. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316070

APA StyleBerkay, E., & Oktay Vehbi, B. (2022). Conservation Proposals for Monasteries in Karpas Peninsula, Northern Cyprus. Sustainability, 14(23), 16070. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316070