The Effects of Internal Market Orientation on Service Providers’ Service Innovative Behavior: A Serial Multiple Mediation Effect on Perceived Social Capital on Customers and Work Engagement

Abstract

1. Introduction

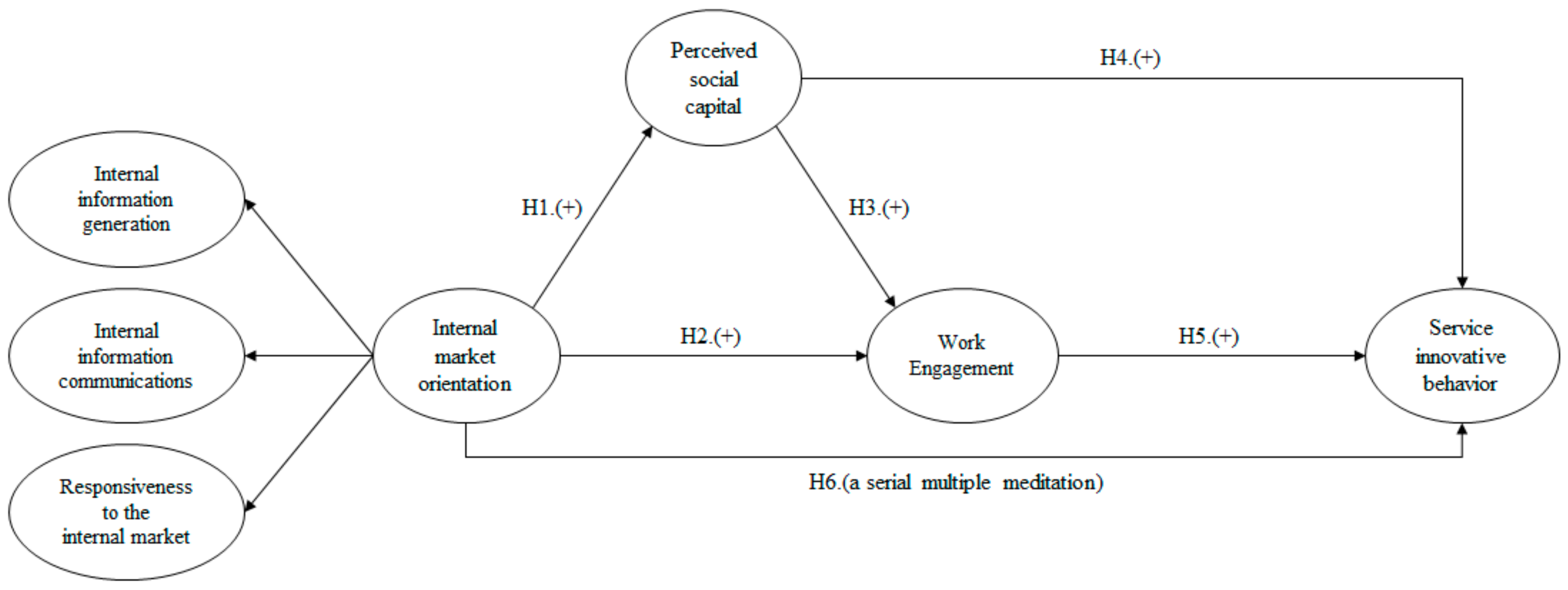

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Internal Market Orientation

2.2. Perceived Social Capital on Customers

2.3. Work Engagement

2.4. Service Innovative Behavior

2.5. The Serial Multiple Mediating Role of Perceived Social Capital on Customers and Work Engagement

3. Research Method

3.1. Data Collection and Participant Characteristics

3.2. Measurement of Variables

4. Analysis Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

4.3. A Serial Multiple Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications

5.2. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grönroos, C. From marketing mix to relationship marketing-towards a paradigm shift in marketing. Manag. Decis. 1994, 32, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harker, M.J. Relationship marketing defined? An examination of current relationship marketing definitions. Mark. Intell. Plan. 1999, 17, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Jain, S.; Dhar, U. CUREL: A scale for measuring customer relationship management effectiveness in service sector. J. Serv. Res. 2007, 7, 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bitner, M.J. Building service relationships: It’s all about promises. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1995, 23, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.R. Strategy is different in service businesses. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1978, 56, 158–165. [Google Scholar]

- Andaleeb, S.S.; Conway, C. Customer satisfaction in the restaurant industry: An examination of the transaction-specific model. J. Serv. Mark. 2006, 20, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.M. A multilevel analysis of the service marketing triangle in theme parks. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. Internal marketing—An integral part of marketing theory. In Marketing of Services; Donnelly, J.H., George, W.E., Eds.; American Marketing Association Proceedings Series: Chicago, IL, USA, 1981; pp. 236–238. [Google Scholar]

- Rafiq, M.; Ahmed, P.K. Advances in the internal marketing concept: Definition, synthesis and extension. J. Serv. Mark. 2000, 14, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Luk, C.L.; Yau, O.H.; Tse, A.C.; Sin, L.Y.; Chow, R.P. Stakeholder orientation and business performance: The case of service companies in China. J. Int. Mark. 2005, 13, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortosa, V.; Moliner, M.A.; Sánchez, J. Internal market orientation and its influence on organisational performance. Eur. J. Mark. 2009, 43, 1435–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, O.H.; Chow, R.P.; Sin, L.Y.; Alan, C.B.; Luk, C.L.; Lee, J.S. Developing a scale for stakeholder orientation. Eur. J. Mark. 2007, 41, 1306–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatignon, H.; Xuereb, J.M. Strategic orientation of the firm and new product performance. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Brouthers, K.D.; Filatotchev, I. Market orientation and export performance: The moderation of channel and institutional distance. Int. Mark. Rev. 2018, 35, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, A.K.; Jaworski, B.J. Market orientation: The construct, research propositions, and managerial implications. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narver, J.C.; Slater, S.F. The effect of a market orientation on business profitability. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A.; Melloy, R.C. The state of the heart: Emotional labor as emotion regulation reviewed and revised. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.S.; Yoo, J. The effects of frontline bank employees’ social capital on adaptive selling behavior: Serial multiple mediation model. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2022, 40, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noopur, N.; Dhar, R.L. Knowledge-based HRM practices as an antecedent to service innovative behavior: A multilevel study. Benchmarking: Int. J. 2020, 27, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.T.; Lee, G. Hospitality employee knowledge-sharing behaviors in the relationship between goal orientations and service innovative behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.J. Is innovation behavior congenital? Enhancing job satisfaction as a moderator. Pers. Rev. 2014, 43, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesil, S.; Sozbilir, F. An empirical investigation into the impact of personality on individual innovation behaviour in the workplace. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 81, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, R.L. Ethical leadership and its impact on service innovative behavior: The role of LMX and job autonomy. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Lyu, B.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y. How does servant leadership influence employees’ service innovative behavior? The roles of intrinsic motivation and identification with the leader. Balt. J. Manag. 2020, 15, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamak, O.U.; Eyupoglu, S.Z. Authentic leadership and service innovative behavior: Mediating role of proactive personality. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 2158244021989629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani-Melhem, S.; Al-Hawari, M.A.; Quratulain, S. Leader-member exchange and frontline employees’ innovative behaviors: The roles of employee happiness and service climate. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2022, 71, 540–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Dhar, R. Employee service innovative behavior: The roles of leader-member exchange (LMX), work engagement, and job autonomy. Int. J. Manpow. 2017, 38, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Koo, D.W. Linking LMX, engagement, innovative behavior, and job performance in hotel employees. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 3044–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Can diversity climate shape service innovative behavior in Vietnamese and Brazilian tour companies? The role of work passion. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, B.; Yıldırım, A. The mediating role of autonomy in the effect of pro-innovation climate and supervisor supportiveness on innovative behavior of nurses. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 22, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Yu, T.F.; Yu, C.C. Knowledge sharing, organizational climate, and innovative behavior: A cross-level analysis of effects. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2013, 41, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hsu, C.H.C. Linking customer-employee exchange and employee innovative behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 56, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hsu, C.H.C. Customer participation in services and employee innovative behavior: The mediating role of interpersonal trust. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2112–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, J.; Zhou, X. Customer cooperation and employee innovation behavior: The roles of creative role identity and innovation climates. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 639531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lings, I.N. Internal market orientation: Construct and consequences. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lings, I.N.; Greenley, G.E. The impact of internal and external market orientations on firm performance. J. Strateg. Mark. 2009, 17, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.R.; Chang, E.; Ou, C.C.; Chou, C.H. Internal market orientation, market capabilities and learning orientation. Eur. J. Mark. 2014, 48, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulki, J.P.; Jaramillo, F.; Goad, E.A.; Pesquera, M.R. Regulation of emotions, interpersonal conflict, and job performance for salespeople. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. Marketing as exchange. J. Mark. 1975, 39, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, D.G.; Shanock, L.R. Perceived organizational support and embeddedness as key mechanisms connecting socialization tactics to commitment and turnover among new employees. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 350–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, E.J. An affect theory of social exchange. Am. J. Sociol. 2001, 107, 321–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Yen, D.A.; Barnes, B.R.; Huang, Y.A. Enhancing firm performance through internal market orientation and employee organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 30, 964–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, M.; Ahmed, P.K. The scope of internal marketing: Defining the boundary between marketing and human resource management. J. Mark. Manag. 1993, 9, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varey, R.J.; Lewis, B.R. A broadened conception of internal marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 1999, 33, 926–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lings, I.N.; Greenley, G.E. Measuring internal market orientation. J. Serv. Res. 2005, 7, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounaris, S. Internal-market orientation and its measurement. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, R.; Hult, G. Innovation, market orientation, and organizational learning: An integration and empirical examination. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, L.; Gray, D. Relational competence, internal market orientation and employee performance. Mark. Rev. 2007, 7, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasser, W.E.; Arbeit, S.P. Selling jobs in the service sector. Bus. Horiz. 1976, 19, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyviou, M.; Croxton, K.L.; Knemeyer, A.M. Resilience of medium-sized firms to supply chain disruptions: The role of internal social capital. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.E.; Le Bon, J.; Rapp, A. Gaining and leveraging customer-based competitive intelligence: The pivotal role of social capital and salesperson adaptive selling skills. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.Y.; Liu, C.W. High performance work systems and organizational effectiveness: The mediating role of social capital. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2015, 25, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. The impact of long-term client relationships on the performance of business service firms. J. Serv. Res. 1999, 2, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Employee orientation and performance: An exploration of the mediating role of customer orientation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswami, S.N. Marketing controls and dysfunctional employee behaviors: A test of traditional and contingency theory postulates. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Defining and measuring work engagement: Bringing clarity to the concept. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Bakker, A.B., Leiter, M.P., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Shimazu, A.; Hakanen, J.; Salanova, M.; De Witte, H. An ultra-short measure for work engagement: The UWES-3 validation across five countries. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2019, 35, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; Bakker, A.B. It takes two to tango: Workaholism is working excessively and working compulsively. In The Long Work Hours Culture: Causes, Consequences and Choices; Burke, R.J., Cooper, C., Eds.; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2008; pp. 203–226. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Hakanen, J.J.; Demerouti, E.; Xanthopoulou, D. Job resources boost work engagement, particularly when job demands are high. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.; Han, S.L. The effects of relationship bonds on bank employees’ psychological responses and boundary-spanning behaviors: An empirical examination of the JD–R model. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 38, 578–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruizalba, J.L.; Bermúdez-González, G.; Rodríguez-Molina, M.A.; Blanca, M.J. Internal market orientation: An empirical research in hotel sector. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 38, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Humphrey, R.H. Emotional labor in service roles: The influence of identity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Larsen, R.J.; Emmons, R.A. Person×Situation interactions: Choice of situations and congruence response models. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 47, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biong, H.; Ulvnes, A.M. If the supplier’s human capital walks away, where would the customer go? J. Bus. -Bus. Mark. 2011, 18, 223–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sony, M.; Mekoth, N. The relationship between emotional intelligence, frontline employee adaptability, job satisfaction and job performance. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 30, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zablah, A.; Franke, G.; Brown, T.; Bartholomew, D. How and when does customer orientation influence frontline employee job outcomes? A Meta-analytic evaluation. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hawari, M.A.; Bani-Melhem, S.; Shamsudin, F.M. Determinants of frontline employee service innovative behavior: The moderating role of co-worker socializing and service climate. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 42, 1076–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, R. Is boreout a threat to frontline employees’ innovative work behavior? J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 32, 574–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Benbasat, I.; Cenfetelli, R.T. The nature and consequences of trade-off transparency in the context of recommendation agents. MIS Q. 2014, 38, 379–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.J.; Yan, R.N.; Eckman, M. Moderating effects of situational characteristics on impulse buying. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2014, 42, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laato, S.; Islam, A.N.; Farooq, A.; Dhir, A. Unusual purchasing behavior during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: The stimulus-organism-response approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasricha, P.; Rao, M.K. The effect of ethical leadership on employee social innovation tendency in social enterprises: Mediating role of perceived social capital. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2018, 27, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolle, A.; Goel, V. Differential impact of beliefs on valence and arousal. Cogn. Emot. 2013, 27, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biron, M.; Van Veldhoven, M. Emotional labour in service work: Psychological flexibility and emotion regulation. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1259–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis with Reading, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q.; Barnes, B.R.; Ye, Y. Internal market orientation, interdepartmental relationships and market performance: The pivotal role of employee satisfaction. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 56, 1464–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lings, I.N.; Greenley, G.E. Internal market orientation and market-oriented behaviours. J. Serv. Manag. 2010, 21, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Items | λa | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal information generation | My company does formal internal market research to find out employees’ feelings about their jobs and the company. | 0.77 ** | 0.88 | 0.76 | 0.87 |

| My company surveys our employees at least once a year to assess the quality of their employment. | 0.85 ** | ||||

| My company has regular staff meetings which discuss what employees want. | 0.80 ** | ||||

| Internal information communications | Before any policy change, managers explain concerns to their employees in advance. | 0.79 ** | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.88 |

| My company usually listen to employees sincerely when they have problems in doing their jobs. | 0.85 ** | ||||

| My company communicates with employees whenever there is a need. | 0.84 ** | ||||

| Responsiveness to the internal market | My company reflects employee needs in job-design, training program selection, and personal development efforts. | 0.77 ** | 0.93 | 0.78 | 0.92 |

| My company periodically review employee development strategies/plans to ensure that they are in line with what employees want. | 0.85 ** | ||||

| Staff policies within my company focuses on real employee needs. | 0.88 ** | ||||

| If my company came up with a great employee development strategy, it will probably be able to implement it in a timely fashion. | 0.88 ** | ||||

| Perceived social capital on customers | My customers and I have developed a close social relationship. | 0.82 ** | 0.91 | 0.80 | 0.84 |

| My customers and I are close business friends. | 0.85 ** | ||||

| The relationship between me and my customers gives me access to valuable information. | 0.75 ** | ||||

| Work engagement | At work, I feel very energetic. | 0.66 ** | 0.88 | 0.63 | 0.92 |

| At my job, I feel strong and vigorous. | 0.71 ** | ||||

| When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to work. | 0.64 ** | ||||

| I am enthusiastic about my job. | 0.79 ** | ||||

| My job inspires me. | 0.76 ** | ||||

| I am proud of the work that I do. | 0.78 ** | ||||

| I feel happy when I am working intensely. | 0.68 ** | ||||

| I am immersed in my work. | 0.68 ** | ||||

| I get carried away when I am working. | 0.62 ** | ||||

| Service innovative behavior | At work, I come up with innovative and creative notions. | 0.71 ** | 0.87 | 0.69 | 0.90 |

| At work, I propose my own creative ideas and convince others. | 0.72 ** | ||||

| At work, I seek new service techniques, methods, or techniques. | 0.80 ** | ||||

| At work, I provide a suitable plan for developing news. | 0.74 ** | ||||

| At work, I try to secure the funding and resources needed to implement innovations. | 0.65 ** | ||||

| Overall, I consider myself a creative member of my team. | 0.69 ** |

| Constructs | λa | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal market orientation | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.90 | |

| Internal information generation | 0.88 ** | |||

| Internal information communications | 0.86 ** | |||

| Responsiveness to the internal market | 0.97 ** |

| Constructs | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. IMO | 3.13 | 0.69 | 0.96 | |||

| 2. Perceived Social Capital | 3.68 | 0.67 | 0.43 | 0.89 | ||

| 3. Work engagement | 3.32 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.79 | |

| 4. SIB | 3.62 | 0.54 | 0.37 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.83 |

| Hypothesized Path | Path Estimates | t-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| IMO → Perceived SC | 0.43 | 6.25 ** | H1. accepted |

| IMO → Work engagement | 0.33 | 5.00 ** | H2. accepted |

| Perceived SC → Work engagement | 0.50 | 6.87 ** | H3. accepted |

| Perceived SC → SIB | 0.30 | 3.37 ** | H4. accepted |

| Work engagement → SIB | 0.34 | 3.69 ** | H5. accepted |

| Path Coefficient | Indirect Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| to Perceived SC | to Work Engagement | to SIB | Estimate | CIlow | CIhigh | |

| IMO | 0.3570 ** | 0.2670 ** | 0.0573 | |||

| Perceived SC | 0.3458 ** | 0.2048 ** | ||||

| Work engagement | 0.2876 ** | |||||

| Total indirect effect | 0.1854 | 0.1261 | 0.2592 | |||

| X → M1 → Y | 0.0731 | 0.0227 | 0.1369 | |||

| X → M2 → Y | 0.0768 | 0.0302 | 0.1384 | |||

| X→M1→M2→Y | 0.0355 | 0.0163 | 0.0585 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, M.-S.; Jeong, G.-Y. The Effects of Internal Market Orientation on Service Providers’ Service Innovative Behavior: A Serial Multiple Mediation Effect on Perceived Social Capital on Customers and Work Engagement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15891. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315891

Lee M-S, Jeong G-Y. The Effects of Internal Market Orientation on Service Providers’ Service Innovative Behavior: A Serial Multiple Mediation Effect on Perceived Social Capital on Customers and Work Engagement. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):15891. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315891

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Myoung-Soung, and Gap-Yeon Jeong. 2022. "The Effects of Internal Market Orientation on Service Providers’ Service Innovative Behavior: A Serial Multiple Mediation Effect on Perceived Social Capital on Customers and Work Engagement" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 15891. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315891

APA StyleLee, M.-S., & Jeong, G.-Y. (2022). The Effects of Internal Market Orientation on Service Providers’ Service Innovative Behavior: A Serial Multiple Mediation Effect on Perceived Social Capital on Customers and Work Engagement. Sustainability, 14(23), 15891. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315891