Abstract

Within the dynamic area of global higher education, international student education plays an important role as an educational resource for students from different countries around the world and ensures inclusive and equitable quality education to create a sustainable future for global citizens. As China’s position in the global international student education landscape continues to rise, international student education in China has entered a stage of improved quality and efficiency. The learning process and outcomes of international students in China have become a key perspective for exploring the quality of international student education in China. This study conducted a questionnaire survey with 1372 international students in China on their study experience in China and found that the learning engagement of international students in China partially mediates the relationship between college environment and study gains. A multi-cluster analysis found that the mediating model of the learning engagement of international students in China was constant across cohorts of students who were second-generation college students (or not), received scholarships (or not), and had different high school backgrounds. Some variability across international student groups of different academic levels and different places of origin occurred. Accordingly, the study makes reference to the three main actors, namely, universities, teachers, and international students, and proposes recommendations for improving the learning engagement and learning gains of international students in China.

1. Introduction

1.1. International Student Education and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations 2030 Agenda outline a vision of a better world that relies on cooperation and interdependence. Higher education plays an important role in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, both as a stand-alone goal (SDG4, Quality Education) and as a central pillar for achieving all 17 goals. Higher education institutions (HEIs) support lifelong learning, quality education, and equity, and provide diverse resources to help prepare global citizens for the challenges of today and tomorrow. They play an important role in creating a sustainable future for all citizens, a goal shared by all 17 SDGs [1]. More specifically, SDG4 aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”. At the heart of these SDGs is the goal of advancing education, which places primary emphasis on universal access to education and recommends that all countries ensure inclusive and equitable education and learning opportunities for all. This goal represents the international education community’s vision and aspiration for 2030 [2]. Among these, SDG 4.3 states that by 2030, equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational, and tertiary education, including university education, should be ensured. Goal 4.7 proposes that by 2030, all people should be equipped with the knowledge and skills needed for sustainable development, including through education for sustainable development, sustainable lifestyles, human rights and gender equality, the promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship, and the affirmation of cultural diversity and the contribution of culture to sustainable development. Goal 4.b proposes that the number of scholarships for higher education must be significantly increased, including for vocational training and ICT, technology, engineering, and science programs, offered globally by developed and selected developing countries for developing countries, in particular LDCs, SIDS, and African countries, by 2020.

As a dynamic area of global higher education, international student education provides educational resources for students from different countries around the world and plays an important role in ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education to create a sustainable future for global citizens. Through international education, international students with global perspectives and respect for other cultures will become global citizens who care for the whole world and will make contributions to form a more inclusive, tolerable, and equal world. Data from China’s Ministry of Education show that 492,185 foreign students of all types from 196 countries and regions studied in 1004 higher education institutions in China in 2018 [3]. China has become the third largest destination after the UK and the US, and the country is set to play a more important place in the global education landscape for international students [4]. China Education Modernization 2035 proposes to build China into a global education highland with an important international influence, attract international outstanding students to study in China, and make China an important destination country in the world for study abroad. The opinions of the Ministry of Education and Other Eight Departments on Accelerating and Expanding the Opening of Education to the World in the New Era also point out that the “Study in China” brand should be strengthened, and efforts should be made to build a global education center with international influence, a study destination for the outstanding young people from around the world.

1.2. International Student Education Has Entered a Stage of Quality Improvement and Efficiency Enhancement

As the scale of international student education has grown considerably, it has also brought about concerns about the quality of education; for example, the quality of students in some institutions needs to be improved, and the management process is not strict enough. With the achievement in student enrolment, improving the quality of international student education has become a new policy priority [5]. In response to the existing problems and to strengthen the brand of “Study in China”, the Chinese Ministry of Education has proposed a change from the “quantitative change” of scale expansion to the “qualitative change” of quality improvement and efficiency enhancement, based on the theme “standardized management, quality and efficiency”. China’s education administrative authorities have also realized the key significance of improving the quality of international students’ education. In October 2018, the Ministry of Education issued the Quality Standards for International Students in Higher Education (for Trial Implementation), which is the first of its kind in China. In October 2018, the Ministry of Education issued the Quality Standards for International Students in Higher Education (for Trial Implementation), which is the first time that China has formulated national-level standards for international students’ education. The document clarifies the concept of connotative development of international students’ education with quality as the core and taking into account the scale, structure, and efficiency, from talent cultivation mode, enrolment, admission, and pre-schooling in the quality of international students [6]. The document also sets out clear and specific requirements for the education and teaching of international students in China in terms of talent training, recruitment, admission, matriculation, education and teaching, management, and service support. For example, universities are required to integrate education for international students into the university-wide education quality assurance system, realize a unified standard teaching management and examination and assessment system, and provide equal and consistent teaching resources and management services. The “Opinions on Accelerating and Expanding the Opening of Education to the Outside World in the New Era” and the “China Education Modernization 2035” are among the national documents that propose to “establish and improve the quality assurance mechanism of education for students studying in China, and comprehensively improve the quality of education for students studying in China” as the development direction and work focus of education for international students.

1.3. Learning Gains as an Important Indicator of the Quality of Education

As an important indicator for evaluating the learning process, measuring the quality of learning and predicting academic achievement, learning gains of university students have become an important issue in the global higher education field in recent years. Eisner [7] was the first to propose a definition of learning outcome, which “essentially refers to the results obtained as a result of some form of participation, whether intentional or unintentional”. Since then, research has progressed, with different researchers offering similar ideas. Fulks [8] argues that learning gains are specific, measurable goals and outcomes that students are expected to achieve as a result of their learning. Kuh [9] suggests that learning gains are defined as the ability of students to demonstrate their knowledge, skills, and values after completing a series of courses or development programs. The Joint Committee on Standards for Educational Evaluation (JCE) takes a widely accepted and applied view of learning gains as what students should know, understand, and be able to do with what they have learned after completing a course, major, or degree. The Joint Committee on Standards for Educational Evaluation (JCSEE) has a view of learning gains as what students should know, understand, and be able to do with what they have learned after completing a course, major, or degree. This includes knowledge and understanding, practical skills, attitudes and values, and individual behavior [10]. Robert Pace proposes a model of learning engagement in which the time and effort students put into their studies, together with their use of school facilities and opportunities, have an impact on their learning gains [11]. Astin [12] constructed an ‘input-environment-output’ (I-E-O) model. The I-E-O model suggests that students’ individual inputs have an impact on learning outputs through the school environment and that students’ demographic characteristics, their learning engagement, and the school environment together influence learning gains. Hu and Kuh [13] proposed a learning productivity model, which suggests that students’ inputs, through individual effort and school environment support, have an impact on final academic achievement. Pascarella [14] proposes a combined student impact model in which school organizational characteristics and students’ backgrounds are external variables, and students’ social interaction, individual effort, school environment factors, and school environment factors have an impact on learning outcomes. In this model, students’ learning and cognitive development are influenced through social interactions, personal effort, and school environment factors. Davis [15] found that the amount of energy students put into their academic and social experiences influenced learning gains. Mahan’s [16] research suggests that there is a significant correlation between school relationships, the quality of the interpersonal environment, changing educational experiences, support for student success, higher-order thinking skills, and learning gains.

1.4. International Students’ Learning Experiences in China

A number of studies have investigated the learning experiences of international students coming to China. For example, Ding’s [17] study investigated international students’ experiences in China, using Shanghai as an example, and found that international students’ satisfaction with their learning experience was low, particularly in terms of class size, teaching methods, teaching materials, and opportunities for one-to-one interaction with teachers. Wen et al. [18] adopted a similar approach and investigated the experiences of international students in Beijing. In contrast to the low satisfaction reported in Ding’s [17] study, Wen et al. [18] found that 83% of participants were satisfied or very satisfied with their study experience in China, although they also identified some key challenges faced by international students, including limited English-language resources, insufficient teacher–student interaction and difficulties with socio-cultural adjustment. MA et al. [5] revealed that the learning experiences of international students coming to China varied, and the international students’ personal traits and cross-cultural environment interacted with their psychological mechanisms to produce and influence their learning experiences. Tian et al.’s [19] two recent studies focused on the experiences of undergraduate international students in China, and the authors noted that students’ engagement with their studies at Chinese institutions was largely unsatisfactory.

Based on the above studies, we can find that international student education is only sustainable if it is of high quality for international students. Conversely, simply pursuing scale expansion while neglecting education quality improvement and management regulation is unlikely to achieve long-term, sustainable development. A review of theories related to learning inputs and benefits reveals that learning benefits are an important lens through which to observe the quality of university education, and exploring them can reveal the particular development trajectory of international students coming to China from a microscopic perspective. International students (or international students) are defined as “people who cross borders in order to study” [20]. Only by fully understanding the experiences of international students in China at university can targeted interventions be made to improve their experiences and enhance the quality of international students’ education. Based on the above background, this study attempts to explore the factors that influence the learning gains of international students in China, based on empirical survey data. How do these factors affect the learning outcomes of international students? This study will explore and analyze the impact of international students’ demographic characteristics, learning inputs, and campus environments on learning outcomes, based on the learning gain theory and the “input-environment-output” model.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Mediating Role of Learning Engagement between College Environment and Learning Gains for International Students Coming to China

Evidence suggests that the level and attributes of personal engagement in academic and non-academic activities appear to play an important role in the success of international students [21]. Student learning engagement includes interactions with teachers, interactions with peers in the curriculum, extracurricular activities, and effort and time invested in learning inside and outside the classroom. The study also found that students who spent more time preparing for courses or otherwise engaged in academic tasks were more satisfied with their overall academic experience. Interaction with teachers was identified as one of the most influential experiences related to overall satisfaction.

In addition to learning engagement, related studies have also shown that the college environment and the perception of the college environment influence students’ learning gains [22] and affect international students’ integration into the college or university campus. Bonazzo and Wong [23] found that Japanese international students experienced prejudice and discrimination in their interactions with students and professors. The study by Constantine et al. [24] also noted that students from some African countries experienced discriminatory and prejudicial treatment by students, staff, and professors. Prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination may influence students’ perceptions of the college environment, which in turn affects their social and academic integration. Research has shown that the social support international students receive helps them integrate into society and that the overall campus climate, in particular, contributes to the academic integration of students. A welcoming and inclusive campus climate provides students with resources, support systems, and interactions that make them feel welcome and accepted as part of the community at large, thus contributing to their social and academic integration [25]. In this regard, the study proposed the hypothesis that:

H1.

International students’ learning engagement significantly affects their learning gains.

H2.

College environment significantly affects international students’ learning engagement.

H3.

College environment significantly affects the learning gains of international students.

2.2. Differences in the Mediating Role of Learning Engagement on Individual Background Variables of International Students Coming to China

Current research on the international student experience tends to treat international students as a homogeneous group, risking overgeneralization and heterogeneity [26]. International students are not a homogeneous group of students. According to Foot [27], international students are influenced by the personal, family, and institutional and national contexts that shape their academic and social experiences. Students from different countries and regions will interact with teachers and access a variety of academic support services in different ways than other international students from different regions, countries and cultures. Studies on learning gains also found that graduate students studying in China had better gains in intercultural competence than undergraduate students studying in China [28], and the self-rated learning gains of non-first-generation college students were significantly higher than those of first-generation college students [29]. Factors, such as grade level, significantly affect students’ learning gains [30]. Based on I-E-O theory, the study also included the educational background of international students before they entered university (high school attendance) and school policy (whether they received scholarships or not) and thus proposed the following hypothesis:

H4.

The mediating effect of learning engagement between college environment and learning gains is significantly different among international students from different regions.

H5.

The mediating effect of learning engagement between college environment and learning gains is significantly different among international students from different grades (academic levels).

H6.

The mediating effect of learning engagement between college environment and learning gains is significantly different among international student groups who are second-generation college students (or not).

H7.

The mediating effect of learning engagement between college environment and learning gains is significantly different among international students who attended different level of high schools.

H8.

The mediating effect of learning engagement between college environment and learning gains is significantly different among international students who received scholarships or not.

The international literature reveals that, firstly, there are few empirical studies on international students’ learning, and there is a lack of studies on the mechanisms that affect their learning gains. Second, empirical research on the learning experiences of international students in China is also in its infancy. Most of the studies are mainly based on cross-cultural psychological perspectives and cross-cultural communication perspectives to study cross-cultural adaptation, and only a few studies have paid special attention to student’s status as “learners”. More studies have focused on international students’ satisfaction surveys rather than their participation or learning processes. Therefore, this study focuses on the mechanisms and effects of learning engagement and college environment on the learning gains of international students in China, with a view to fill the gaps in relevant empirical studies and provide targeted suggestions and references to enhance learning gains and improve the learning experience of international students in China.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Study Population

The study received responses from 1400 international students from 96 countries studying in 82 Chinese universities through an online questionnaire survey, of which 1372 questionnaires were valid, with an effective rate of 98.0%. Of the survey sample, 944 (68.8%) were male students, 428 (31.2%) were female students, 722 (52.6%) were undergraduate and matriculation students, 650 (47.4%) were postgraduate students, 845 (61.6%) were Asian students, 435 (31.7%) were African students, and 92 (6.7%) were students from other countries or regions. There were 711 students (51.8%) who were second-generation university students, 1026 students (74.8%) who received scholarship or bursary support, and 648 students (47.2%) who attended high schools in the top 50% of their country or region.

3.2. Research Tools

The College Student Experiences Questionnaire (CSEQ) was developed by the American scholar Pace in 1970 and was introduced to China by Professor Zuoyu Zhou of Beijing Normal University in 2001. The Chinese College Student Experiences Questionnaire (CCSEQ) was developed by Professor Zuoyu Zhou of Beijing Normal University in 2001 and has been administered and revised several times. Considering that the target population of this survey is international students in China, the study takes into account the characteristics of international students in China and the changes in teaching and learning styles brought about by external factors, such as the New Crown epidemic, and revises the molecular scale on the basis of the two versions of the CCSEQ in China and the United States.

3.2.1. Questionnaire on Demographic Variables

This part of the questionnaire is designed to investigate the basic background information of international students coming to China, such as gender, grade, nationality, scholarship status, and high school attendance, and consists of 17 questions. Compared with the original questionnaire (CCSEQ), the questions on the characteristics of international students include the status of the participant’s high school in their country, their religious beliefs, and whether they have had any experience of taking courses or studying abroad before coming to China.

3.2.2. Learning Engagement Scale

The scale covers the subdimensions of students’ course learning, teacher-student interaction, activities using campus facilities, personal experiences, conversation topics and conversation messages. Forty-six questions are asked on a 4-point scale from 1 (never) to 4 (often), with higher scores indicating higher student engagement in the activity. An exploratory factor analysis of the engagement in learning scale revealed a KMO value of 0.945 (>0.90) for the sphericity test and χ² = 13,695.904 (df = 1035, p < 0.001) for the Bartlett’s sphericity test, indicating that the data were suitable for factor analysis. Factors were extracted using the principal component method, six factors were extracted according to the original structure, and a great variance rotation was performed. Finally, a total of 19 questions were removed from the Learning Engagement Scale, and 27 questions were retained, with a commonality of between 0.493 and 0.728, with the six factors explaining 60.244% of the total variance. The empirical factor analysis found that the model was reasonably well conceived, with all fit indices above 0.9 (GFI = 0.923; IFI = 0.935; TLI = 0.926; CFI = 0.935), an RMSEA of 0.046 (<0.08) and a chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio of 2.449 (χ² = 756.744; df = 309). The internal consistency reliability coefficient of the Learning Engagement Scale was 0.914, and the subdimension reliability coefficients ranged from 0.664 to 0.856, which met the measurement criteria.

3.2.3. College Environment Scale

Students’ perception and awareness of the characteristics of the university environment is important to consider when describing the university environment. The college environment scale is used to reflect students’ perceptions of the school environment and interpersonal relationships related to personal development. The scale contains 10 questions that allow students to rate the college environment that promotes all aspects of student development (academic, artistic, diversity, critical, informational, professional, values education, etc.) and perceived interpersonal relationships with peers, administrators, and teachers, using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (very low priority) to 7 (very high priority) and 1 (competitive, stereotypical, inaccessible relationships) to 7 (friendly, helpful, approachable relationships) on a scale of 1–7, with higher scores representing higher student satisfaction with the college environment.

An exploratory factor analysis of the college environment scale revealed a KMO value of 0.936 (>0.90) for the sphericity test and χ² = 4579.061 (df = 45, p < 0.001) for Bartlett’s sphericity test, indicating that the data were suitable for factor analysis. Factors were extracted using the principal component method, with 2 factors extracted according to the original structure and a great variance rotation done. From the results, the distribution of loadings for each factor was consistent with theory, the commonality of topics ranged from 0.654 to 0.762, and the 2 factors together explained 72.742% of the total variance, indicating good structure and no need for topic deletion. The empirical factor analysis found that all model fit indices were above 0.9 (GFI = 0.960; IFI = 0.979; TLI = 0.972; CFI = 0.979), the RMSEA was 0.066 (<0.08) and the chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio was 3.927 (χ² = 133.507; df = 34), indicating that the model was reasonably well conceived and could be considered the college environment as a two-dimensional model consisting of 2 factors. The internal consistency reliability coefficient of the College Environment Scale was 0.925, and the subdimension reliability coefficients were 0.837 and 0.935, respectively, which met the measurement criteria.

3.2.4. Learning Gains Scale

The learning gains Scale covers students’ gains in five areas: vocational preparation, general education, intellectual skills, personal development, and scientific and technological skills. Twenty-five questions are asked on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 (very little) to 4 (a lot), with higher scores representing more gains in this area.

An exploratory factor analysis of the learning gains scale revealed a KMO value of 0.960 (>0.90) for the sphericity test and χ² = 10,018.350 (df = 300, p < 0.001) for the Bartlett’s sphericity test, indicating that the data were suitable for factor analysis. Factors were extracted using the principal component method, with five factors extracted according to the original structure and a great variance rotation done. Finally, a total of seven questions were removed from the scale, leaving 18 questions with a commonality between 0.573 and 0.793, with a total of 68.805% of the total variance explained by the five factors. The empirical factor analysis found that all model fit indices were above 0.9 (GFI = 0.930; IFI = 0.954; TLI = 0.944; CFI = 0.954), the RMSEA was 0.060 (<0.08), and the chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio was 3.381 (χ² = 422.670; df = 125), indicating that the model was reasonably well conceived. The learning gains Scale had an internal consistency reliability coefficient of 0.931 and subdimension reliability coefficients between 0.757 and 0.863, which met the measurement criteria.

3.3. Data Analysis Methods

In examining the structural validity of the scale, the data obtained from the measurement were randomly divided into two parts, half of which were used for exploratory factor analysis EFA and the other half for confirmatory factor analysis CFA. Exploratory factor analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0, and validating factor analysis was performed using Amos 24.0. In addition, the study mainly used SPSS 25.0 for the reliability analysis and correlation analysis of the full sample and Amos 24.0 for the mediation model test and multiple cluster analysis. Considering that the chi-squared value is affected by the sample size, the study evaluated the fit of the model using a combination of fit indices such as comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), incremental fit index (IFI), goodness of fit Index (GFI) and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). Among the fit indices, GFI, CFI, IFI, and TLI values greater than 0.90 and RMSEA values less than 0.08 could be used as criteria to evaluate the goodness of fit of the model.

3.4. Common Method Bias Test

The Harman one-way method was used to test for the presence of common method bias. An exploratory factor analysis was conducted on all questionnaire questions, and it was found that the eigenvalues of a total of 23 factors without rotation were greater than 1. The amount of variation explained by the first factor was 15.31%, which was less than the 40% critical criterion. This leads to the conclusion that common method bias was not significant in this study.

4. Results

4.1. The Mediating Role of International Students’ Learning Engagement in the Relationship between College Environment and Learning Gains

The correlation analysis of learning engagement, college environment, and learning gains among international students found that there was a positive correlation between learning engagement, college environment, and learning gains, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.1 to 0.7 (all significant at the 0.001 level). Based on the results of the correlation analysis and the theoretical hypotheses, the mediating role of learning input in the relationship between college environment and learning gains was examined with college environment as the independent variable and learning gains as the dependent variable. The results of the confirmatory factor analysis for each scale under the full sample condition were tested, as shown in Table 1, and the model fit was good enough for structural equation modelling. According to the procedure of the mediating effect test, the model of the direct effect of college environment on the learning gains of international students in China was first analyzed. In the model, the college environment was used as a latent variable, including two observed variables, namely, campus culture and interpersonal relationships, while learning gains was also used as a latent variable in the model, including five observed variables, namely, career preparation, general education, intellectual skills, personal development, and technological competence. The model fit indicators obtained from the structural equation modelling analysis are shown in Table 2. The direct model fit was good, the path coefficient of college environment on learning gains was significant (γ = 0.52, p < 0.001), and the direct effect of college environment on learning gains was 0.516.

Table 1.

The results of confirmatory factor analysis.

Table 2.

Fit index results of the model.

The model was well fitted by introducing incoming international students’ learning engagement as a mediating variable. After adding the mediating variable, the positive effect of college environment on learning gains was still significant, but the path coefficient changed from 0.52 to 0.40 (p < 0.001); meanwhile, college environment had a positive effect on learning input (γ = 0.34, p < 0.001), and the positive effect of learning input on learning gains was significant (γ = 0.34, p < 0.001). The model was tested for mediating effects using the bootstrap method, setting up 5000 repeated samplings with a confidence interval of 95%. If the confidence interval does not include 0, then the indirect effect is not equal to 0, which means that the mediating effect is significant. The results of the test showed that the 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect of college environment on learning gains was [0.087, 0.152] and that a confidence interval that did not include 0 indicated that the indirect effect was not equal to 0, i.e., the mediating effect of learning engagement was significant. This indicates that the college environment can affect learning gains directly or indirectly through learning engagement and that learning engagement partially mediate the effect between college environment and learning gains. The mediating effect accounted for 22.4% of the total effect size (0.116/0.518). Studies have shown that undergraduates’ participation in college activities greatly affects their academic achievement [31], dropout rate [32], and educational gains [33]. Students will benefit from the time and energy invested in meaningful educational activities [34,35]. Chi et al. [36] also found that students’ learning engagement mediates the college environment and intellectual development. The results of this study on international students can be mutually corroborated with existing studies.

4.2. Testing the Constancy of the Mediating Role of Learning Engagement across Different Student Groups

To test the constancy of the model across different groups, this study was conducted through two main stages. In the first stage, the model testing procedure for a single sample occurred. Based on the mediation model that has been validated in the full sample, the model of mediation effects across different groups was tested separately, and if there was a certain degree of fit, the second stage of model constancy testing could be carried out. If the fit was poor under either sample, then the constancy did not hold and the best model discussed separately in the respective groups.

In the second stage, a multigroup constancy test was performed. This can be done by testing the variation in model fit under various constant assumptions through a series of progressively restricted nested models, including unconstrained model (M0): i.e., the model is morphologically constant (Morphological constancy refers primarily to the fact that the factor structure and model structure are identical in appearance (e.g., number of observed and latent variables and correspondence, influence of relationships between latent variables, etc.) across groups. At this point, there is no real restriction that any parameters are equal across groups); measurement weight (M1): the main test is whether the relationship between the observed and potential variables is equal across clusters. M2: the regression coefficients in the structural model are equal, i.e., the path coefficients of the model are equal across groups; structural covariance. M3: the covariance of the structure is added to the structural loadings and the covariance. If the covariance and variance of a structure are constant, then the relationship between the potential variables can be reproduced in different groups (there is a stricter equality of structural and measurement residuals after the number of structural variances, but the constancy of error variances is generally considered too stringent for practical validation of theoretical models and is of lesser importance [37]. In this study, we consider that the model is restricted to M3 to account for cross-group constancy and do not discuss it further).

Regarding the criteria for determining equality, first, morphological equality is judged by the fitness of the model M0 (i.e., the model fit index), and if the model fit index meets the requirements, the model is considered to be morphologically constant across clusters. On the basis of morphological constancy, the model can be further judged on the basis of the significance of Δχ² between the models. When the cardinality of the restricted model is significant compared to that of the free model, it means that the model constancy does not hold under that restricted condition. However, as χ² is strongly influenced by the sample and can easily be significant when the sample size is large, the researcher suggests combining situations, such as ΔTLI and ΔCFI, to determine whether the cardinality is significant in practice. Specifically, significance is considered significant when ΔTLI is greater than 0.02 and ΔCFI is greater than 0.01 [38], i.e., this is the case before constancy is considered not to hold on the corresponding model.

The specific findings of the study are as follows.

4.2.1. Test of Constancy between Cohorts of Second-Generation College Students

As shown in Table 3, the fit of the models in both the second-generation college student and non-second-generation college student cohorts met the requirements, and the results of further multi-cluster analyses showed that all the fit indices of M0–M3 were within the acceptable range. The difference between each model and the free model was not significant, the difference between each fit index ΔCFI and ΔTLI was less than 0.01, and the significance of Δχ² was greater than 0.05, indicating that the models in the second-generation models have cross-group constancy between second-generation college students and non-second-generation college students.

Table 3.

Test of constancy between cohorts of second-generation university students.

4.2.2. Test of Constancy between Groups of Students with Different Scholarship Statuses

As shown in Table 4, the RMSEA of the model in the scholarship group was 0.081, which was slightly higher than 0.08, but the other indicators GFI, IFI, TLI, and CFI were all higher than 0.9. Basically, it can be considered that the model fits reasonably well in the scholarship group and can be combined with the non-scholarship group for multigroup analysis. The results of further multi-cluster analysis showed that all the fit indices from M0 to M3 were within the acceptable range, the differences between M0, M1, and M2 were not significant, and the differences between the fit indices ΔCFI and ΔTLI were less than 0.01, indicating that the model structure, factor loadings, and regression paths were equal between the scholarship and non-scholarship groups. However, the Δχ² for M3 compared to M2 reached a significant level, suggesting that there may be differences in the number of variation/covariates in the model between the two groups. Further comparison of the difference in CR of the covariates revealed that the differences were not significant. In summary, the combination of ΔCFI and ΔTLI (less than 0.01) can be considered insignificant differences between the models, i.e., the models are constant across the scholarship and non-scholarship groups. Yeh [39] conducted a survey on Asian international graduate students and found that students’ awards (scholarships and grants) were highly correlated with their learning gains. These related conclusions from different studies reveal that different demographic variables may have different effects on students’ learning gains, which is of great interest to explore.

Table 4.

Test of constancy between groups of students with different scholarship status.

4.2.3. Test of Constancy between Cohorts of Students at Different Levels

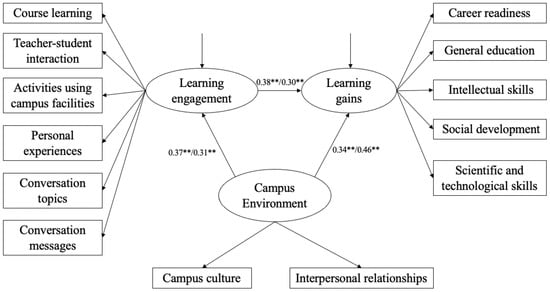

Bista [40] found that academic level significantly predicted learning gains: graduate students had higher learning gains than undergraduates. The study categorized students enrolled in matriculation and undergraduate years 1 to 4 as the undergraduate cohort, and students enrolled in master’s and doctoral studies as the postgraduate cohort. As shown in Table 5, the fit of the model was found to be satisfactory for both the undergraduate and postgraduate cohorts, and further results of the multi-cluster analysis showed that all fit indicators from M0 to M3 were within acceptable limits. Specifically, the differences in fit indices ΔCFI and ΔTLI between M1 and M0 were less than 0.01, and the significance of Δχ² was greater than 0.05, indicating that the model was constant in terms of measurement loadings. However, Δχ² between M2 and M1 is significant, suggesting that the path coefficients may not be congruent in both groups. Further comparison of the path coefficients for international students at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels in the free model at this point revealed that the difference between the two groups reached borderline significance for the one path coefficient from college environment to learning gains (ΔCR = 1.757, with an absolute value greater than 1.645, i.e., significant at the 0.10 level), as shown in Figure 1. For the international student group at the undergraduate level, the college environment (γ = 0.34, p < 0.001) had a positive effect on learning engagement (γ = 0.37, p < 0.001) and a significant positive effect of learning engagement on learning gains (γ = 0.38, p < 0.001) for the international student group at the postgraduate level. For the international student group at the postgraduate level, the college environment also has a significant positive effect on learning gains (γ = 0.46, p < 0.001). (γ = 0.46, p < 0.001), and this effect was stronger for the graduate-level group than for the undergraduate-level group (ΔCR = 1.757), while the college environment had a positive effect on learning engagement (γ = 0.31, p < 0.001) and a significant positive effect of learning engagement on learning gains (γ = 0.30, p < 0.001).

Table 5.

Test of constancy between cohorts of students at different levels.

Figure 1.

Model differences between undergraduate and postgraduate students (undergraduate/postgraduate). Note. ** p < 0.01.

Using the bootstrap method to test the significance of the mediating effect for the undergraduate and postgraduate groups, the results showed that the 95% confidence intervals for the mediating effect of university activities in the two groups were [0.091, 0.194] and [0.055, 0.137], respectively, meaning that the mediating effect of learning engagement was significant in both groups. At this point, the mediated effect size for the undergraduate international student group was 0.139, accounting for a total effect size of 0.139/0.478 = 29.1%, and the mediated effect size for the postgraduate international student group was 0.092, accounting for 0.092/0.548 = 16.8%.

4.2.4. Tests of Constancy between Student Cohorts from Different Origins

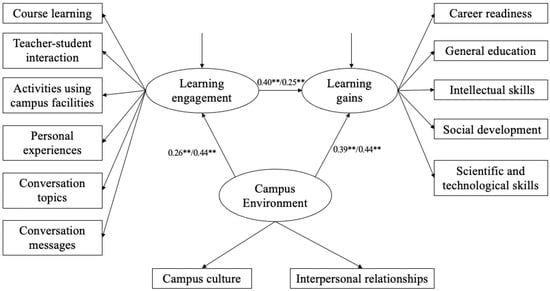

Considering the distribution of the sample, the study divided the group of international students coming to China into Asian and non-Asian students. As shown in Table 6, the models of the two groups fit well, and the results of further tests of constancy from M0 to M3 show that between M1 and M0, the differences in each fit index ΔCFI and ΔTLI are less than 0.01, and the significance of Δχ² is greater than 0.05, indicating that the models have constancy in terms of measurement loadings. However, Δχ² is significant between M2 and M1, suggesting that the path coefficients may not be congruent in the two groups. Further comparison of the path coefficients between Asian and non-Asian international students in the free model revealed that the two groups differed significantly in the one path coefficient from college environment to learning engagement (ΔCR = −2.007, absolute value greater than 1.96), as shown in Figure 2: for the Asian international student group, there was a significant positive effect of college environment on learning gains (γ = 0.39, p < 0.001), as well as a significant positive effect of college environment on learning engagement (γ = 0.26, p < 0.001) and a significant positive effect of learning engagement on learning gains (γ = 0.40, p < 0.001); for the non-Asian international student group, there was also a significant positive effect of college environment on learning gains (γ = 0.44, p < 0.001), as well as a significant positive effect of college environment had a significant positive effect on learning engagement (γ = 0.44, p < 0.001), the path coefficient was significantly larger than that in the Asian group (ΔCR = −2.007), and the positive effect of learning engagement on learning gains was significant (γ = 0.25, p < 0.001).

Table 6.

Test of constancy between student cohorts from different origins.

Figure 2.

Model differences between Asian students and non-Asian students (Asian students/non-Asian students). Note. ** p < 0.01.

Using the bootstrap method to test the significance of the mediating effect separately for the Asian and non-Asian student groups, the results showed that the 95% confidence intervals for the mediating effect of university activities in the two groups were [0.064, 0.146] and [0.054, 0.174], respectively, meaning that the mediating effect of university activities was significant in both groups. At this point, the mediated effect size for the Asian student group was 0.103, accounting for 0.103/0.496 = 20.8% of the total effect size, and the mediated effect size for the non-Asian student group was 0.108, accounting for 0.108/0.550 = 19.6%.

An empirical study highlighted the importance of cultural background, Ward and Kennedy [41] found that Malaysian students in Singapore encountered fewer problems than those in New Zealand, while Chinese students in Singapore adapted more easily than Anglo-European students. The similarity between the student’s culture of origin and the cultural environment of the host country is an important factor. More similarity means less difficulty in the overseas experience [42]. These results also prove the possible influence of campus environment, especially cultural environment, on students’ learning engagement and learning gains. Students from Asia are more likely to adapt to the Chinese culture, while students from non-Asia may face more difficulties in adapting to the Chinese college environment. These results explain the positive effect of college environment on the learning engagement of non-Asian international students from China was significantly higher than that of Asian international students from China.

4.2.5. Test of Constancy between Different Groups of High School Students

Based on I-E-O (input-environment-output) theory [12], the study took into account the importance of the prior experience of students, and added the type of high school to reflect different levels of education resource allocation and the level of education quality that students could have in high schools. The study categorized the students according to their high school they attended, namely from the top 50% of high schools in their country and the bottom 50% of high schools. As shown in Table 7, the fit of the model among the two different groups of high school students met the requirements, and the results of the multi-cluster analysis showed that the fit indices of M0~M3 were all within the acceptable range. The difference between the models and the free model was not significant, the difference between the fit indices ΔCFI and ΔTLI was less than 0.01, and the significance of Δχ² was greater than 0.05, indicating that the model had cross-cluster constancy between the top 50% and the bottom. The model had cross-group constancy between the top 50% and the bottom 50% of the international student population.

Table 7.

Test of constancy between different groups of high school students.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Conclusion

5.1.1. There Is a Partial Mediating Effect of International Students’ Learning Engagement between College Environment and Learning Gains

The study found that the p values of all the dimensions of learning engagement, college environment, and learning gains were less than 0.01, and the correlation coefficients were positive, indicating that there was a significant positive relationship between learning engagement, college environment and learning gains. The correlation coefficients were positive, indicating that the relationship between international students’ study commitment, college environment and learning gains was significant and positive. The original hypotheses H1, H2, and H3 are valid. This indicates that the college environment not only affects the learning gains of international students directly but also influences the learning gains of international students through the mediation of learning engagement. This supports the theory of the I-E-O model and further enriches the study that the external environment affects the final learning gains through the internal inputs. The perception of a good college environment and interpersonal interaction among international students will promote and motivate international students to participate and engage in learning activities and thus learn more. According to this study we can conclude that only by creating a good campus environment, promoting the learning engagement of international students and enhancing their learning gains, can we create a high-quality international student education, thus forming a sustainable international student education.

5.1.2. The Mediating Role of Learning Engagement Varies across Cohorts and Different Origin Groups of International Students

The study found that the mediating model of learning engagement among international students in China was constant across cohorts of students who were second-generation undergraduates (or not), received scholarships (or not), and had different high school backgrounds. However, the positive effect of college environment on the learning gains of international students from China at the graduate level was significantly higher than that of international students from China at the undergraduate level, and the positive effect of college environment on the learning engagement of non-Asian international students from China was significantly higher than that of Asian international students from China. This indicates that the development of postgraduate international students is more likely to be influenced by the college environment than that of undergraduate students and that a good college environment and interpersonal interaction are more motivating for non-Asian international students to engage in various learning activities. This finding confirms hypotheses H4 and H5, while Hypotheses H6, H7, and H8 are not valid. The international student community is not a single, unified group; students come from different cultural backgrounds and enjoy different cultural norms. There are relative similarities and heterogeneity in the incoming international student community. Therefore, supportive campus initiatives and environments need to go beyond the binary thinking of local and international students and should also be sensitive to the differences between international student groups.

5.2. Policy Implications

5.2.1. Universities Should Provide Support for International Students in Their Studies and Lives through a Range of Institutional Provisions

Given the importance of different activities of engagement and social support for international students studying in a foreign country, institutions should actively provide services for international students in terms of learning and social resources, such as training in library information and usage skills, language and study skills training, psychological counselling services, and support for student organization groups. In the development of strategies of internationalization, universities must focus on local students and engage them in cross-cultural interactions with global attitudes, skills, and approaches, reduce the gap between the living spaces of international students and local students, and create conditions to facilitate interaction between home and international students. In addition, this study reveals that the learning gains of international students vary according to their region of origin and type of study stage, and the results highlight the problems associated with considering international students in China as a homogeneous group. In this regard, universities and researchers need to regularly evaluate statistics to better understand learning among different groups of international students.

5.2.2. Teachers Need to Improve Their Attention to the Individual Development Needs of International Students and Help Enhance Their Learning Gains in China

Teachers are an important social resource for international students, helping them make initial adjustments to their local environment, facilitating interactions with local students, and providing experience and advice on their academic programs and long-term career goals. Teachers should therefore focus not only on teaching international students’ specialist knowledge but also language skills, intercultural competence, and other generic skills and qualities. In the classroom, teachers should emphasize active interaction with international students to promote deeper learning and enhance their learning gains. As the number of international students continues to grow, the international student population is also becoming more diverse. Universities are faced with a diverse group of students from different countries, different socioeconomic backgrounds, different learning motivations and foundations, and different career aspirations. Teachers need to pay attention to the individual development needs of each international student and help them to improve their perception of China and promote their commitment to learning.

5.2.3. International Students Should Enhance Their Self-Motivation and Actively Participate in Different Types of Educational Learning Activities

International students themselves should actively participate in different types of education-based learning activities. First, international students should enhance their self-confidence and motivation, actively participate in classroom learning, and interact with teachers and local students. Second, international students should cherish and seize the opportunities provided by the university to participate in various campus activities, actively make use of various campus facilities, participate in various academic and research activities or club activities, enrich their study experience, enhance their understanding and perception of the institution and China, expand their skills and knowledge structure in various aspects, effectively enhance their learning gains and truly achieve success.

It is important to note that there are still some shortcomings in this study, which need to be enriched and improved by subsequent studies. On the one hand, there is still room for further improvement in the study in terms of the differences in the impact mechanisms of learning gains among different groups of international students. For example, in terms of the origin of international students in China, the study classifies them into Asian and non-Asian due to the distribution of the sample; future research needs to see the differences in the impact mechanisms of learning gains among international students from different countries or regions. On the other hand, although the study examined the relationship between college environment and international students’ learning engagement and learning gains, it lacked a value-added or tracking perspective to analyze the long-term impact and changes in college environment and learning engagement on international students’ learning gains, which needs to be further explored in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M. and C.S.; literature review, Y.W.; methodology, C.S.; project administration, J.M.; writing—original draft, J.M. and C.S.; writing—review and editing, J.M. and C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Educational Science Foundation of Beijing “International Comparative Study on Global International Student Mobility Policies and Initiatives” major project (No. ABAA2020050).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- European University Association (EUA). Universities without Walls—A Vision for 2030; European University Association: Brussel, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://eua.eu/resources/publications/957:universities-without-walls-%E2%80%93-eua%E2%80%99s-vision-for-europe%E2%80%99s-universities-in-2030.html (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Yasmin, F.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Poulova, P.; Akbar, A. Unveiling the International Students’ Perspective of Service Quality in Chinese Higher Education Institutions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Statistics on Study in China in 2018. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/gzdt_gzdt/s5987/201904/t20190412_377692.html (accessed on 12 April 2019). (In Chinese)

- Ma, J. Characteristics, challenges and trends of global international student education under the wave of counter-globalization. Educ. Res. 2020, 10, 134–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Zhao, K. International student education in China: Characteristics, challenges, and future trends. High. Educ. 2018, 4, 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. The Quality Standards for International Students in Higher Education (for Trial Implementation). 2018. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A20/moe_850/201810/t20181012_351302.html (accessed on 9 October 2018). (In Chinese)

- Eisner, E. The Educational Imagination; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Fulks, J. Assessing Student Learning in Higher Education. 2009. Available online: http://online.Bakersfieldcollege.edu/courseassessment/Section_2_Background/Section2_2WhatAssessment.htm (accessed on 21 April 2019).

- Kuh, G.; Hu, S. Learning Productivity at Research Universities. J. High. Educ. 2001, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullickson, A. The Student Evaluation Standards: How to Improve Evaluations of Students; Educational Policy Leadership Institute: California, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kuh, G.; Ikenberry, S. More Than You Think, Less Than We Need: Learning Outcomes Assessment in American Higher Education. National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment. 2009. Available online: https://www.learningoutcomesassessment.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/2009NILOASurveyReport.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Astin, A. What Matters in College? Four Critical Years Revisited. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Kuh, G. Maximizing What Students Get Out of College: Testing a Learning Productivity Model. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2003, 2, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascarella, E. College Environmental Influences on Learning and Cognitive Development: A Critical Review and Synthesis; Agathon: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, T.; Murrell, P. A Structural Model of Perceived Academic, Personal and Vocational Gains related to College Student responsibility. Res. High. Educ. 1993, 3, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahan, D. The Four-year Experience of First Generation Students at a Small Independent University: Engagement, Student Learning, and Satisfaction. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X. Exploring the experiences of international students in China. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2016, 20, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Hu, D.; Hao, J. International students’ experiences in China: Does the planned reverse mobility work? Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2018, 61, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Lu, G.; Li, L. Assessing the quality of undergraduate education for international students in China: A perspective of student learning experiences. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2022, 5, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Education at Glance 2017. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/education-at-a-glance-2017_eag-2017-en (accessed on 12 September 2017).

- Elspeth, J. Problematising and reimagining the notion of ‘international student experience’. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 5, 933–943. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. A study on the influence of college environment support on academic master’s learning gains. Shandong High. Educ. 2019, 2, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bonazzo, C.; Wong, Y. Japanese International Female Students’ Experience of Discrimination, Prejudice, and Stereotypes. Coll. Stud. J. 2007, 3, 631–639. [Google Scholar]

- Constantine, M.G.; Kindaichi, M.; Okazaki, S.; Gainor, K.A.; Baden, A.L. A Qualitative Investigation of the Cultural Adjustment Experiences of Asian International College Women. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2005, 2, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, G. International Ph. Students in Australian Universities: Financial Support, Course Experience and Career Plans. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2003, 23, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanassab, S. Diversity, international students, and perceived discrimination: Implications for educators and counselors. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2006, 10, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foot, J.R. Exploring International Student Academic Engagement Using the NSSE Framework. Ph.D Thesis, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.J. Study on the Factors Influencing the Learning Gains of International Students Coming to China in Jinan University. Master’s Thesis, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China, 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Long, Y.; Wang, Y. The impact of student-teacher interaction on learning gains: An analysis of the differences between first-generation and non-first-generation college students. Explor. High. Educ. 2018, 12, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. An Empirical Study on the Factors Influencing College Students’ Learning Gains. Master’s Thesis, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China, 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zilvinskis, J. Using Authentic Assessment to Reinforce Student Learning in High-Impact Practices. Assess. Update 2015, 6, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astin, A. Preventing Students from Dropping Out; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Alnusair, D.M. An Assessment of College Experience and Educational Gains of Saudi Students Studying at U.S. Colleges and Universities. Ph.D. Thesis, George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hakes, C.J. Off-Campus Work and Its Relationship to Students’ Experiences with Faculty Using the College Student Experiences Questionnaire. Ph.D. Thesis, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Utami, N.D.; Regina; Wardah. An analysis on students’ effort to improve speaking skill. J. Pendidik. Dan Pembelajaran 2015, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, X.; Liu, J.; Bai, Y. College environment, student involvement, and intellectual development: Evidence in china. High. Educ. 2017, 1, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Testing for multigroup invariance using AMOS graphics: A road less travelled. Struct Equ. Model. 2004, 2, 272–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indices for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 2, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, H.C. College Student Experiences among Asian International Graduate Students at the University of Denver. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Denver, Denver, CO, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bista, K.K. Asian International Students’ College Experiences at Universities in the United States: Relationship between Perceived Quality of Personal Contact and Self-Reported Gains in Learning. Ph.D. Thesis, Arkansas State University, Jonesboro, AR, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, C.; Kennedy, A. The measurement of sociocultural adaptation. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 1999, 4, 659–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.A.; Bochner, S.; Furnham, A.F. The Psychology of Culture Shock; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).