The Use of Level Based Weight Assessment (LBWA) for Evaluating Public Participation on the Example of Rural Municipalities in the Region of Warmia and Mazury

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The number of comparisons of the applied criteria is reduced, which speeds up the evaluation and reduces subjectivity.

- Unlike in other multi-criteria methods, the complexity of the calculation procedure does not increase rapidly with an increase in the number of criteria. Therefore, the LBWA model is more resistant to changes in the number of criteria, and it can be effectively used in procedures where the required number of criteria becomes apparent only in the successive stages of research.

- In the process of sorting criteria, decision makers can present their preferences in the form of a logical algorithm. In the LBWA model, the optimal values of weighting coefficients are calculated with a simple mathematical apparatus that eliminates inconsistencies from expert preferences, which are tolerated in some subjective models (BWM and AHP).

2. Background Literature

3. Materials and Methods

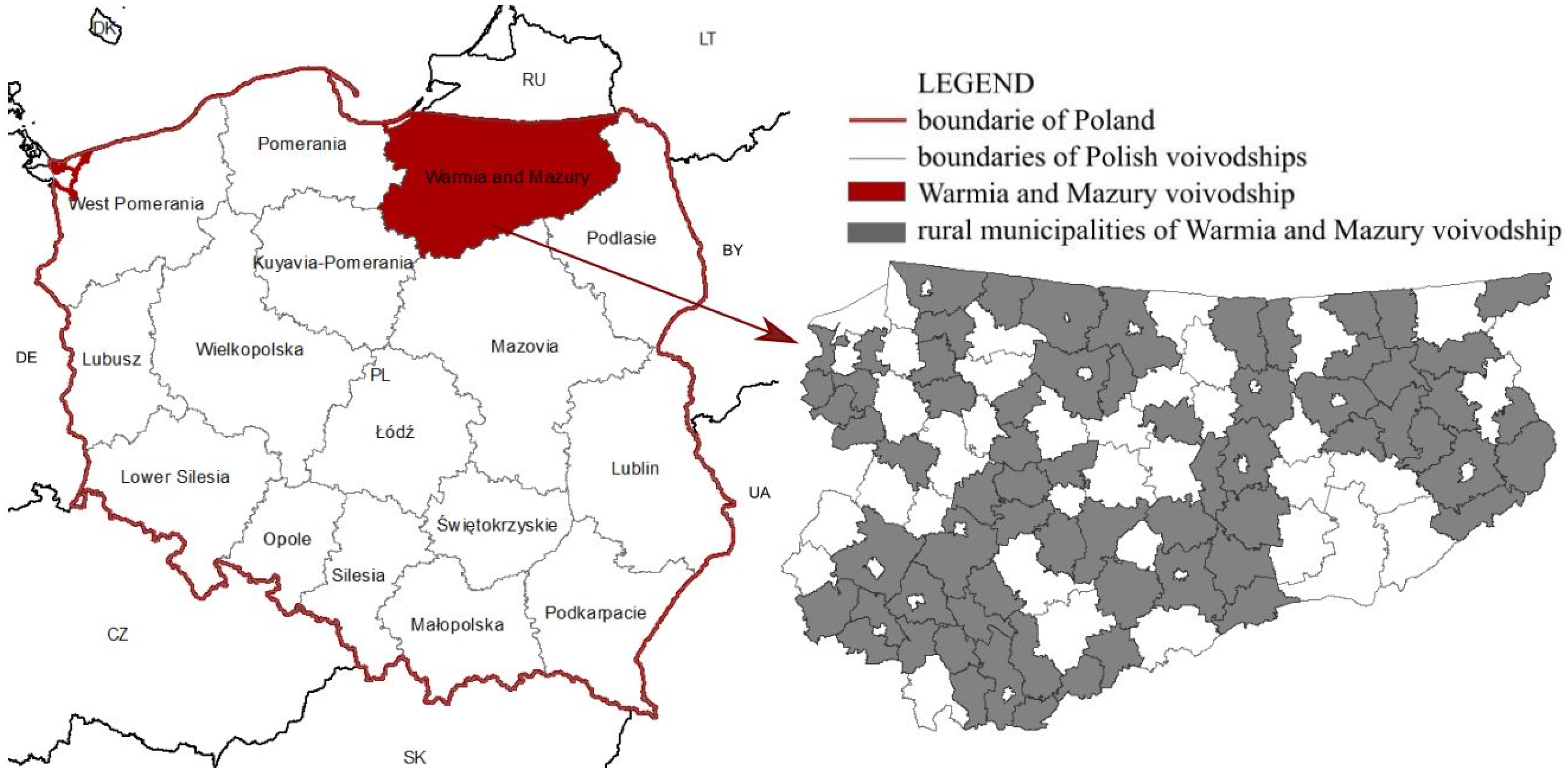

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Methods

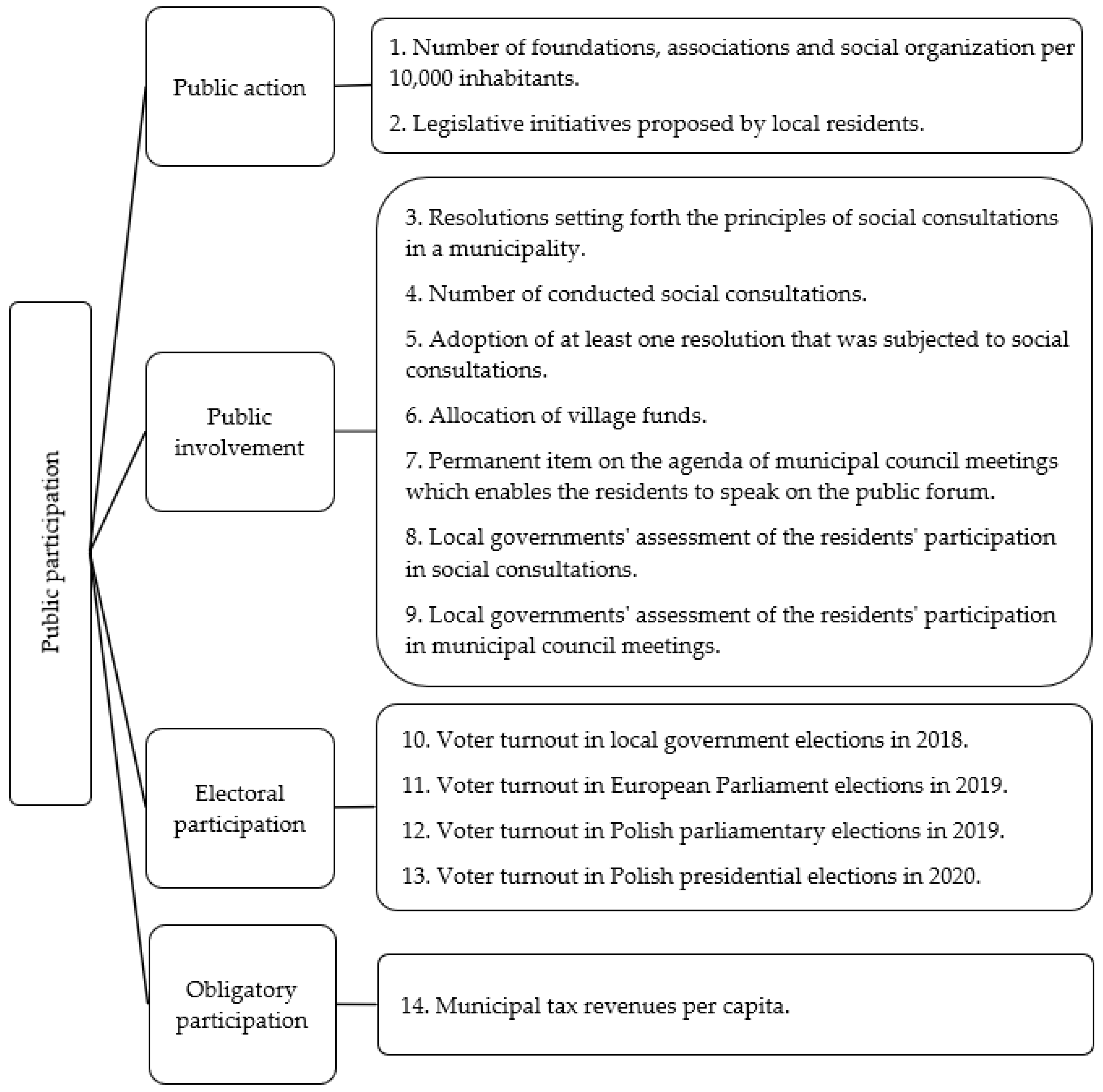

- The criteria characterizing the four types of public participation in the life of a municipality were identified and described with the use of fourteen indicators (Figure 2) based on a review of the literature [12,30,31,33,39,44,47,56]. Data for the study were obtained from the National Electoral Commission [57], Local Data Bank of Statistics Poland [51], and a survey of local self-government representatives in rural municipalities of the Region of Warmia and Mazury.

- A system of weights was developed with the use of the Level Based Weight Assessment (LBWA) method. In this approach, the importance of various criteria is determined with the use of a multi-criteria model M containing a set of criteria S {C1, C2,…, Cn} with n number of elements [23,25,27,28,58]. The following procedure was applied to assign weights to the criteria for evaluating public participation in the LBWA method:

- 3.

- The indicators for evaluating public participation were normalized. Real-world data from various sources were transformed to point values to facilitate a comparison of the results and perform statistical calculations. The result of the measurement was compared with the maximum and minimum values of the same category in the entire set. This comparison was performed on a scale of 0 (minimum value of the measurement in the entire set) to 100 points (maximum value). The number of points for the remaining results (between extreme values) was calculated with the use of the following formula [61]:where:

- Yj—points assigned to a single measurement;

- xj.max—maximum result;

- xj.min—minimum result;

- xj—result estimated in each measurement.

- 4.

- Based on its importance, the influence of each criterion was evaluated in subsets (levels of influence) and its rank in the group was determined. If criterion Cip ϵ Si, where Si ={Ci1, Ci2,…, Cis}, this criterion is assigned the value Iip ϵ {0,1,…, r} in such a way that the most important criterion C1 is assigned the value I1 = 0. However, if criterion Cip is more important than Ciq, then Ip < Iq. If criterion Cip is equivalent to Ciq, then Ip = Iq. The maximum value on the importance scale was defined as r = max {│S1│, │S2│, …, │Sk│}.

- 5.

- The elasticity coefficient r0 ϵ N was calculated based on the defined value of max r. N is a set of real numbers which meet the condition r0 > r.

- 6.

- The function describing the influence of the analyzed criteria was expressed as f: S → R. An influence function stating that if Cip ϵ Si then:where:

- i—level where the criterion was classified;

- r0—elasticity coefficient;

- Iip—value of importance assigned to criterion Cip at level Si,

was calculated for each criterion. - 7.

- The optimal weighting coefficients were calculated for each criterion. The weight for criterion CEX was calculated as follows:The weights for successive criteria were calculated as follows:where:wj = f(Cj) · wEX,,

- j = 2, 3,…, n;

- n–successive criteria.

- 8.

- The synthetic indicator for each municipality was calculated with the below formula:where:

- j—number of indicators evaluated in the study area.

- 9.

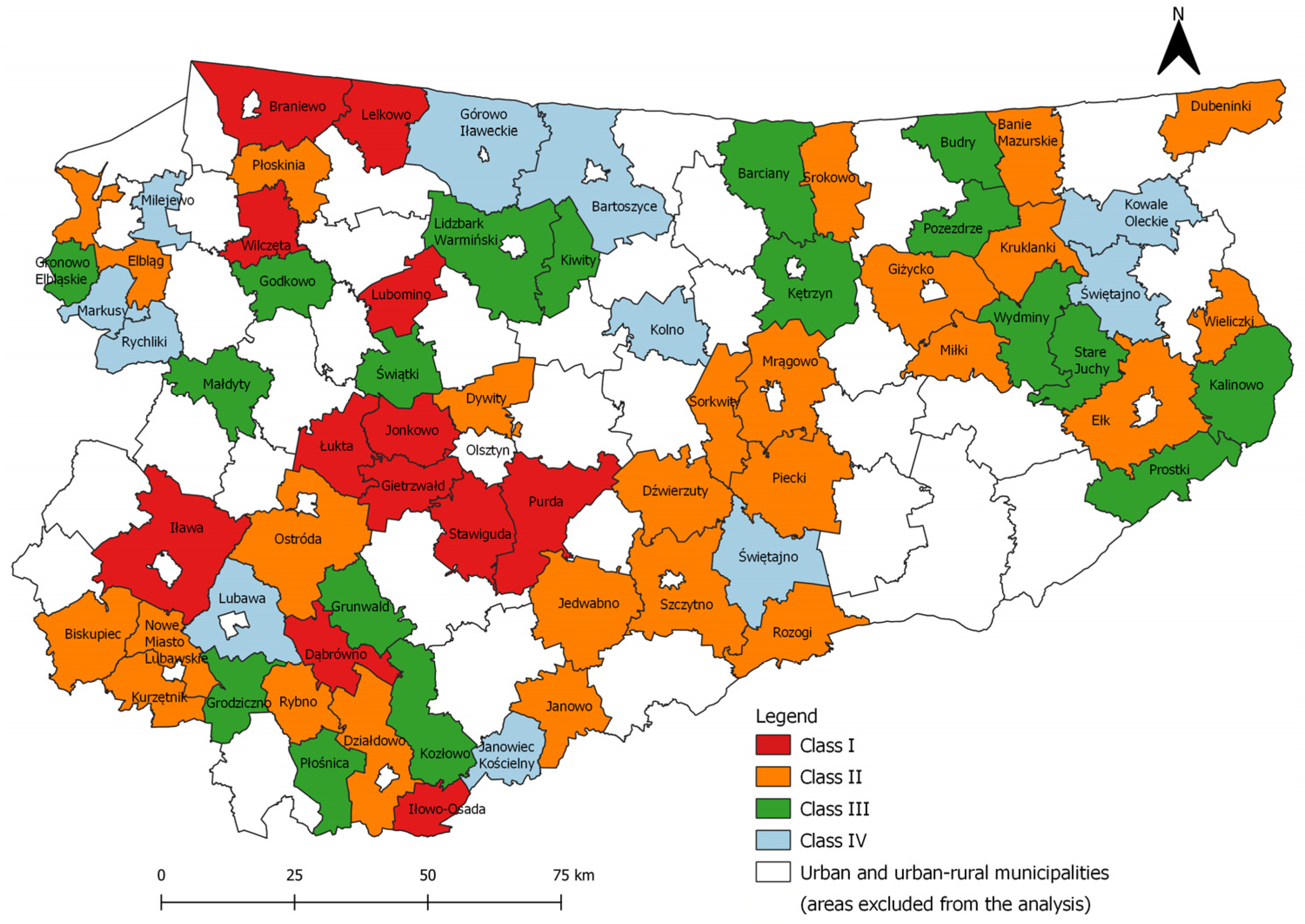

- The municipalities were ranked and classified. The Jenks natural breaks classification method was used for that purpose [62]. This method is applied to divide natural groups of data into classes. Data are classified by grouping similar values and maximizing differences between classes. The objects are divided into classes whose boundaries are determined based on relatively large differences in values [63]. Four typological classes describing different levels of importance were ultimately determined: class I—high, class II—medium-high, class III—medium-low, and class IV—low.

4. Results

4.1. Assigning Weights to Selected Indicators of Social Participation in Municipalities

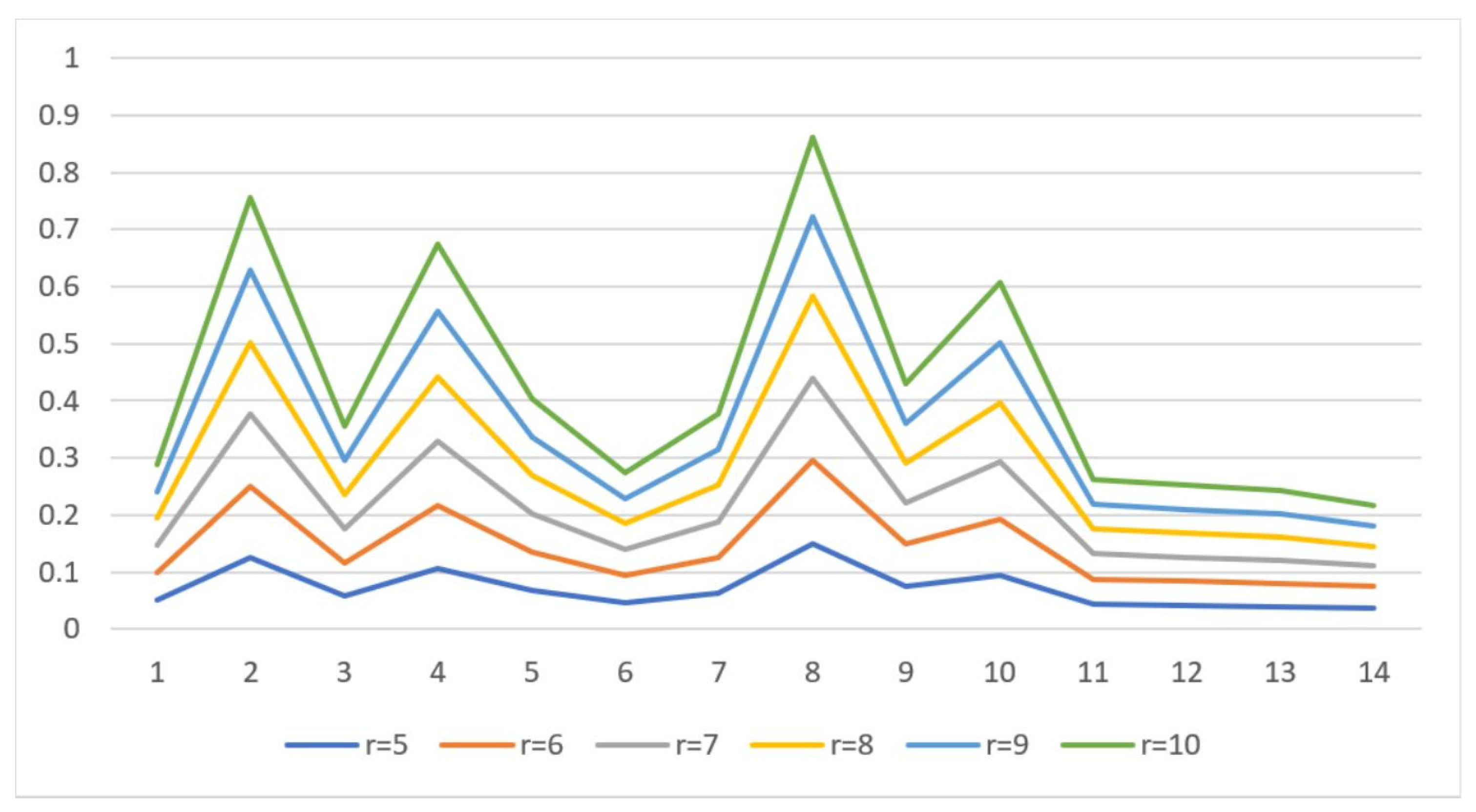

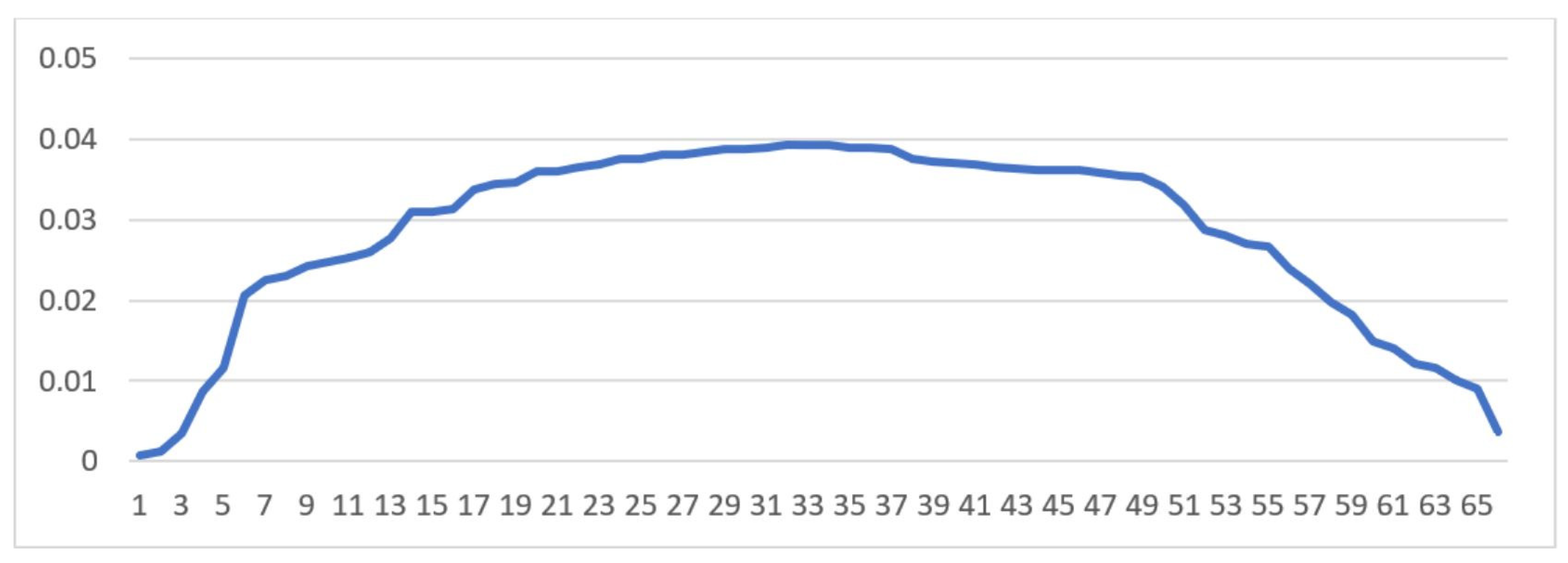

4.2. Analysis of the Influence of Coefficient r0 on Weight Values

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumaniecki, K.F. Słownik Łacińsko-Polski, 7th ed.; Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Warszawa, Poland, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Kopaliński, W. Słownik Wyrazów Obcych i Zwrotów Obcojęzycznych, 20th ed.; BMJ Biblioteka Miłośników Języka; Wiedza Powszechna: Warszawa, Poland, 1990; ISBN 83-214-0790-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ostaszewski, K. Partycypacja Społeczna w Procesie Podejmowania Rozstrzygnięć w Administracji Publicznej; Wydawnictwo KUL: Lublin, Poland, 2013; ISBN 978-83-7702-708-0. [Google Scholar]

- Długosz, D.; Wygnański, J.J. Obywatele Współdecydują: Przewodnik po Partycypacji Społecznej; Stowarzyszenie na Rzecz Forum Inicjatyw Pozarządowych: Warszawa, Poland, 2005; ISBN 83-914980-9-3. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, L.J. Civic Pa view. In Social Research, Research Findings; 2005; p. 14. Available online: https://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/3000/https://www.gov.scot/Resource/Doc/57346/0016705.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Mahendran, K.; Cook, D. Participation and Engagement in Politics and Policy Making: Building a Bridge between Europe and Its Citizens—Evidence Review Paper One. 2007. Available online: https://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20160118214131mp_/http://www.gov.scot/Resource/Doc/163759/0044572.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Piasecki, A.K. Samorząd Terytorialny i Wspólnoty Lokalne, 1st ed.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2009; ISBN 978-83-01-15898-9. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, O. Public Engagement in Global Context: Understanding the UK Shift towards Dialogue and Deliberation. 2010. Available online: https://eresearch.qmu.ac.uk/handle/20.500.12289/2230 (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Fudge Schormans, A. Social Participation. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 6135–6140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, J.H. The Impact of Citizen Participation on Public Administration. Public Adm. Rev. 1972, 32, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creighton, J.L. The Public Participation Handbook: Making Better Decisions through Citizen Involvement; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005; ISBN 0-7879-7307-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kaźmierczak, T. Partycypacja Publiczna: Pojęcie, Ramy Teoretyczne. In Partycypacja Publiczna. O uczestnictwie Obywateli w Życiu Wspólnoty Lokalnej; Olech, A., Ed.; Instytut Spraw Publicznych: Warszawa, Poland, 2011; pp. 83–99. ISBN 978-83-7689-070-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, S.H.; Norazizan, S.; Nikkhah, H.A. Conflicting Perceptions on Participation between Citizens and Members of Local Government. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1761–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlewicz, K.; Pawlewicz, A. Interregional Diversity of Social Capital in the Context of Sustainable Development—A Case Study of Polish Voivodeships. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-P.; Sun, T.-W.M. Public Participation. In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance; Farazmand, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 5171–5181. ISBN 978-3-319-20928-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hajduk, S. Partycypacja Społeczna w Zarządzaniu Przestrzennym w Kontekście Planistycznym; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Białostockiej: Białystok, Poland, 2021; ISBN 978-83-66391-56-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zamelski, P. Wybrane Koncepcje Dobra Wspólnego w Ujęciu Prawnonaturalnym i Normatywnym. In Efektywność Europejskiego Systemu Ochrony Praw Człowieka. Ewolucja i Warunkowania Europejskiego Systemu Ochrony Praw Człowieka. Część I: Współczesne Rozumienie Praw Człowieka; Jaskiernia, J., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek: Warszawa, Poland, 2012; pp. 180–205. ISBN 978-83-7780-235-9. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development AGENDA 21. In Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on Environment & Development, Rio de Janeirio, Brazil, 3–4 June 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Economic Development. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development—Implementation in Poland. 2017. Available online: https://www.mr.gov.pl/media/41562/broszura_onz_en_ost.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Groeger, L. Udział Społeczny a Zrównoważony Rozwój Przestrzeni Mieszkaniowej. Studia Miej. 2012, 5, 58–76. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, L.H.; Koski, J.; Verkuijl, C.; Strambo, C.; Piggot, G. Making Space: How Public Participation Shapes Environmental Decision-Making; Stockholm Environment Institute: Seattle, WA, USA, 2019; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterhof, P.D. Localizing the Sustainable Development Goals to Accelerate Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Gov. Brief 2018, 33, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žižović, M.; Pamučar, D. New Model for Determining Criteria Weights: Level Based Weight Assessment (LBWA) Model. Decis. Mak. Appl. Manag. Eng. 2019, 2, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamučar, D.; Faruk Görçün, Ö. Evaluation of the European Container Ports Using a New Hybrid Fuzzy LBWA-CoCoSo’B Techniques. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 203, 117463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamučar, D.; Žižović, M.; Marinković, D.; Doljanica, D.; Jovanović, S.V.; Brzaković, P. Development of a Multi-Criteria Model for Sustainable Reorganization of a Healthcare System in an Emergency Situation Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korucuk, S.; Aytekin, A.; Ecer, F.; Pamucar, D.S.S.; Karamaşa, Ç. Assessment of Ideal Smart Network Strategies for Logistics Companies Using an Integrated Picture Fuzzy LBWA–CoCoSo Framework. Manag. Decis. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božanić, D.; Jurišić, D.; Erkić, D. LBWA—Z-MAIRCA Model Supporting Decision Making in the Army. Oper. Res. Eng. Sci. Theory Appl. 2020, 3, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, N.; Pamucar, D.; Amine, M.S.M.E. Application of a D Number Based LBWA Model and an Interval MABAC Model in Selection of an Automatic Cannon for Integration into Combat Vehicles. Def. Sci. J. 2021, 71, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveci, M.; Özcan, E.; John, R.; Covrig, C.-F.; Pamucar, D. A Study on Offshore Wind Farm Siting Criteria Using a Novel Interval-Valued Fuzzy-Rough Based Delphi Method. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 270, 110916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, G.P.; Haines, A. Asset Building & Community Development, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4833-4403-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bashir, S. Analytical Study of Community Development Programs for Socio-Economic Development in Pakistan. Ph.D Thesis, University of Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Portal Organizacji Pozarządowych Poradnik. Co to są Organizacje Pozarządowe? Available online: https://poradnik.ngo.pl/co-to-sa-organizacje-pozarzadowe-czym-jest-stowarzyszenie-a-czym-fundacja (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Pokładecki, J. Partycypacja a Lokalny System Polityczny. East. Rev. 2018, 7, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustawa z dnia 8 Marca 1990 r. o Samorządzie Gminnym (Dz.U2022 Poz. 559). Available online: https://Isap.Sejm.Gov.Pl/Isap.Nsf/DocDetails.Xsp?Id=WDU20220000559 (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Marchaj, R. Ustawa o Samorządzie Gminnym: Komentarz; Dolnicki, B., Ed.; Komentarze Praktyczne; 3. wydanie, stan prawny na 1 lutego 2021 r.; Wolters Kluwer: Warszawa, Poland, 2021; ISBN 978-83-8223-217-2. [Google Scholar]

- Czopek, M.; Żołnierczyk, E. Konsultacje Społeczne Jako Forma Dialogu Ze Społecznością Lokalną. Społeczności Lokalne Studia Interdyscyplinarne 2017, 1, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wenclik, M. Statut Gminy—Modelowe Rozwiązania w Zakresie Partycypacji Publicznej. In Przepis na Udane Konsultacje Społeczne; Fundacja Laboratorium Badań i Działań Społecznych "SocLab": Białystok, Poland, 2014; pp. 7–20. ISBN 978-83-63870-06-5. [Google Scholar]

- Maszkowska, A. Regulamin Konsultacji Społecznych—Modelowe Rozwiązania. In Przepis na Udane Konsultacje Społeczne; Fundacja Laboratorium Badań i Działań Społecznych "SocLab": Białystok, Poland, 2014; pp. 21–42. ISBN 978-83-63870-06-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sześciło, D. Jak zwiększyć udział obywateli w zarządzaniu gminą? Formy partycypacji i dobre praktyki. 2015. Available online: https://www.maszglos.pl/materialy-edukacyjne/jak-zwiekszyc-udzial-obywateli-w-zarzadzaniu-gmina-formy-partycypacji-i-dobre-praktyki/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Sitniewski, P. Jawność Obrad Rad Miejskich i Rad Powiatów w Polsce; Jawnośc i kompetencja VII; Fundacja Centrum Inicjatyw na Rzecz Społeczeństwa: Białystok, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chochowski, K. Zasada Pomocniczości Jako Zasada Ustrojowa. IJOLS 2020, 8, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltynowski, M. Local Initiatives for Green Space Using Poland’s Village Fund: Evidence from Lodzkie Voivodeship. Bull. Geogr. 2020, 50, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustyniak, M. Fundusz Sołecki—Nowy Instrument Gospodarki Finansowej w Sołectwie. Przegląd Prawa Publicznego 2010, 9, 58–69. [Google Scholar]

- Heywood, A. Key Concepts in Politics; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2000; ISBN 1-4039-3210-7. [Google Scholar]

- Cześnik, M. Partycypacja Wyborcza Polaków; Instytut Spraw Publicznych: Warszawa, Poland, 2009; ISBN 987-83-7689-024. [Google Scholar]

- Leszczyńska, K. Udział Obywateli w Wyborach i Referendach w Polsce Po 1989 Roku. East. Rev. 2018, 7, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masango, R. Public Participation in Policy-Making and Implementation with Specific Reference to the Port Elizabeth Municipality. Ph.D Thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tyszka, P. Zadania Prawa Karnego Skarbowego i Praktyczne Możliwości Ich Realizacji. Prokur. Prawo 2007, 1, 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Uchwała Nr 155 Rady Ministrów z Dnia 27 Października 2020 r. w Sprawie Przyjęcia “Strategii Rozwoju Kapitału Społecznego (Współdziałanie, Kultura, Kreatywność) 2030.”. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WMP20200001060 (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Uchwała Nr 8 Rady Ministrów z Dnia 14 Lutego 2017, r. w Sprawie Przyjęcia Strategii Na Rzecz Odpowiedzialnego Rozwoju Do Roku 2020 (z Perspektywą Do 2030 r.). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WMP20170000260 (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- GUS—Bank Danych Lokalnych [Statistics Poland—Lacal Data Bank]. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/bdl/start (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Warmińsko-Mazurskie 2030. Strategia Rozwoju Społeczno-Gospodarczego. 2020. Available online: https://strategia.warmia.mazury.pl/strategia-2030/ (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Milenkovic, N.; Vukmirovic, J.; Bulajic, M.; Radojicic, Z. A Multivariate Approach in Measuring Socio-Economic Development of MENA Countries. Econ. Model. 2014, 38, 604–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgado Molina, M.D.M.; Salinas Fernandez, J.A.; Rodriguez Martin, J.A. A Synthetic Indicator to Measure the Economic and Social Cohesion of the Regions of Spain and Portugal. Rev. Econ. Mund. 2015, 39, 223–240. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, A.G.; Lopez, M.H.; Echeverria, F.R. A Methodological Approach for Obtaining Sustainable Development Synthetic Indicators for Venezuela. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2016, 12, 118–132. [Google Scholar]

- Goś-Wójcicka, K.; Nałęcz, S.; Wojtkowiak-Jakacka, M. Pozyskanie Nowych Wskaźników Dotyczących Realizacji Usług Publicznych z Zakresu Partycypacji Społecznej; Centrum Badań i Edukacji Statystycznej GUS: Warszawa, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Państwowa Komisja Wyborcza [National Election Committee]. Available online: https://pkw.gov.pl (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Biswas, S.; Majumder, S.; Pamucar, D.; Dawn, S.K. An Extended LBWA Framework in Picture Fuzzy Environment Using Actual Score Measures Application in Social Enterprise Systems. IJEIS 2021, 17, 37–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodgson, J.; Spackman, M.; Pearman, A.; Phillips, L. Multi-Criteria Analysis: A Manual; Department for Communities and Local Government: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4098-1023-0.

- Cieślak, I. Identification of Areas Exposed to Land Use Conflict with the Use of Multiple-Criteria Decision-Making Methods. Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajadacz, A. Potencjał Turystyczny Miast na Przykładzie Wybranych Miast Sudetów Zachodnich; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2004; ISBN 83-89290-59-6. [Google Scholar]

- de Smith, M. Statistical Analysis Handbook. A Comprehensive Handbook of Statistical Concepts, Techniques and Software Tools; The Winchelsea Press: Winchelsea, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-912556-08-3. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Yang, S.T.; Li, H.W.; Zhang, B.; Lv, J.R. Research on Geographical Environment Unit Division Based on the Method of Natural Breaks (Jenks). Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2013, XL-4/W3, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konsultacjezzasadami.Pl. Available online: http://www.konsultacjezzasadami.pl/regulamin-konsultacji-spolecznych.html (accessed on 7 August 2022).

- The World Bank. Public Consultation in Environmental Assessment: Lessons from East and South Asia. In Social Development Notes; 1997; Volume 30, Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/11592 (accessed on 7 August 2022).

- Zychowicz, Z. Konsultacje Społeczne w Samorządzie, 1st ed.; Instytut Rozwoju Regionalnego: Szczecin, Poland, 2014; ISBN 978-83-88312-20-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pankowski, K. Spadek Poczucia Podmiotowości Obywatelskiej; Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej: Warszawa, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital. In Culture and Politics: A Reader; Crothers, L., Lockhart, C., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan US: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 223–234. ISBN 978-1-349-62965-7. [Google Scholar]

- Donderowicz, M.; Główczyński, M.; Wronkowski, A. Partycypacja społeczna w rewitalizacji-rola stowarzyszeń lokalnych na przykładzie Poznania. Probl. Rozw. Miast 2016, 4, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Roguska, B. Wybory Do Parlamentu Europejskiego; Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Koniuszewska, E. Obywatelska inicjatywa uchwałodawcza. Acta Iuris Stetin. 2019, 27, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, A. Frekwencja wyborcza. In Zachowania Polityczne; Dalton, R.J., Klingemann, H.-D., Markowski, R., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2010; Volume 2, pp. 237–256. ISBN 978-83-01-16315-0. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, R.A. Demokracja i Jej Krytycy; Aletheia: Warszawa, Poland, 2012; ISBN 978-83-61182-96-2. [Google Scholar]

- Cybulska, A.; Pankowski, K. Chcemy Chodzić Na Wybory—Deklaracje o Uczestnictwie i Ocena Rangi Wyborów; Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pankowski, K. Wybory Samorządowe a Poczucie Podmiotowości Obywatelskiej; Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cybulska, A.; Pankowski, K. Decyzje Wyborcze w Wyborach Samorządowych 2018; Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cybulska, A.; Pankowski, K. Motywy Głosowania w Wyborach Samorządowych 2018; Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Molska, K. Analiza Frekwencji w Wyborach Parlamentarnych. Przykład Województwa Zachodniopomorskiego. In Systemy Polityczne i Partyjne w Ujęciu Teoretycznym i Praktycznym; Kamińska-Korolczuk, K., Mielewczyk, M., Ożarowski, R., Eds.; Między teorią a praktyką funkcjonowania systemów politycznych i partyjnych; Uniwersytet Gdański: Gdańsk, Poland, 2016; pp. 241–264. ISBN 978-83-64970-09-2. [Google Scholar]

- Roguska, B. Motywy Głosowania w Wyborach Prezydenckich 2020; Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cybulska, A.; Pankowski, K. Jak Polacy Podejmowali Decyzje w Wyborach Parlamentarnych w 2019 Roku; Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pankowski, K. Społeczne Reakcje Na Wynik Wyborów; Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cybulska, A.; Pankowski, K. Decyzje w Wyborach Do Parlamentu Europejskiego. Przyczyny Absencji Wyborczej; Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Neneman, J. Finanse lokalne obywateli–ile spójności, ile autonomii? Samorz. Teryt. 2015, 1–2, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Omyła-Rudzka, M. Postawy Wobec Płacenia Podatków; Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej: Warszawa, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Cj | Indicator | I | Iip |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Number of foundations, associations, and social organization per 10,000 inhabitants | 3 | 0 |

| 2 | Legislative initiatives proposed by the residents | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | Resolutions setting forth the principles of social consultations in a municipality | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | Number of conducted social consultations | 1 | 2 |

| 5 | Adoption of at least one resolution that was subjected to social consultations | 2 | 1 |

| 6 | Allocation of village funds | 3 | 1 |

| 7 | Permanent item on the agenda of municipal council meetings which enables the residents to speak on the public forum | 2 | 2 |

| 8 | Local governments’ assessment of the residents’ participation in social consultations | 1 | 0 |

| 9 | Local governments’ assessment of the residents’ participation in municipal council meetings | 2 | 0 |

| 10 | Voter turnout in local government elections in 2018 | 1 | 3 |

| 11 | Voter turnout in European Parliament elections in 2019 | 3 | 2 |

| 12 | Voter turnout in Polish parliamentary elections in 2019 | 3 | 3 |

| 13 | Voter turnout in Polish presidential elections in 2020 | 3 | 4 |

| 14 | Municipal tax revenues per capita | 4 | 0 |

| r0 = 5 wEX = 0.150 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Criterion | f(Cj) | wj |

| C1 | 0.333 | 0.050 |

| C2 | 0.833 | 0.125 |

| C3 | 0.385 | 0.058 |

| C4 | 0.714 | 0.107 |

| C5 | 0.455 | 0.068 |

| C6 | 0.313 | 0.047 |

| C7 | 0.417 | 0.063 |

| C8 = CEX | 1.000 | 0.150 |

| C9 | 0.500 | 0.075 |

| C10 | 0.625 | 0.094 |

| C11 | 0.294 | 0.044 |

| C12 | 0.278 | 0.042 |

| C13 | 0.263 | 0.040 |

| C14 | 0.250 | 0.038 |

| Total | 6.659 | 1.000 |

| wEX | 0.150 | 0.147 | 0.144 | 0.142 | 0.140 | 0.139 |

| r0 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| C1 | 0.050 | 0.049 | 0.048 | 0.047 | 0.047 | 0.046 |

| C2 | 0.125 | 0.126 | 0.126 | 0.126 | 0.126 | 0.126 |

| C3 | 0.058 | 0.059 | 0.059 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 0.060 |

| C4 | 0.107 | 0.110 | 0.112 | 0.114 | 0.115 | 0.116 |

| C5 | 0.068 | 0.068 | 0.067 | 0.067 | 0.066 | 0.066 |

| C6 | 0.047 | 0.046 | 0.046 | 0.045 | 0.045 | 0.045 |

| C7 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.063 |

| C8 = CEX | 0.150 | 0.147 | 0.144 | 0.142 | 0.140 | 0.139 |

| C9 | 0.075 | 0.073 | 0.072 | 0.071 | 0.070 | 0.070 |

| C10 | 0.094 | 0.098 | 0.101 | 0.103 | 0.105 | 0.107 |

| C11 | 0.044 | 0.044 | 0.044 | 0.044 | 0.044 | 0.043 |

| C12 | 0.042 | 0.042 | 0.042 | 0.042 | 0.042 | 0.042 |

| C13 | 0.040 | 0.040 | 0.040 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.041 |

| C14 | 0.038 | 0.037 | 0.036 | 0.035 | 0.035 | 0.035 |

| Total | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Max | Min | Mean | SD | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 71.37 | 20.71 | 42.79 | 42.16 | 42.16 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pawlewicz, K.; Cieślak, I. The Use of Level Based Weight Assessment (LBWA) for Evaluating Public Participation on the Example of Rural Municipalities in the Region of Warmia and Mazury. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13612. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013612

Pawlewicz K, Cieślak I. The Use of Level Based Weight Assessment (LBWA) for Evaluating Public Participation on the Example of Rural Municipalities in the Region of Warmia and Mazury. Sustainability. 2022; 14(20):13612. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013612

Chicago/Turabian StylePawlewicz, Katarzyna, and Iwona Cieślak. 2022. "The Use of Level Based Weight Assessment (LBWA) for Evaluating Public Participation on the Example of Rural Municipalities in the Region of Warmia and Mazury" Sustainability 14, no. 20: 13612. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013612

APA StylePawlewicz, K., & Cieślak, I. (2022). The Use of Level Based Weight Assessment (LBWA) for Evaluating Public Participation on the Example of Rural Municipalities in the Region of Warmia and Mazury. Sustainability, 14(20), 13612. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013612