An Unsustainable Smart City: Lessons from Uneven Citizen Education and Engagement in Thailand

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. A Smart City and Its Citizens

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Thailand’s Smart City

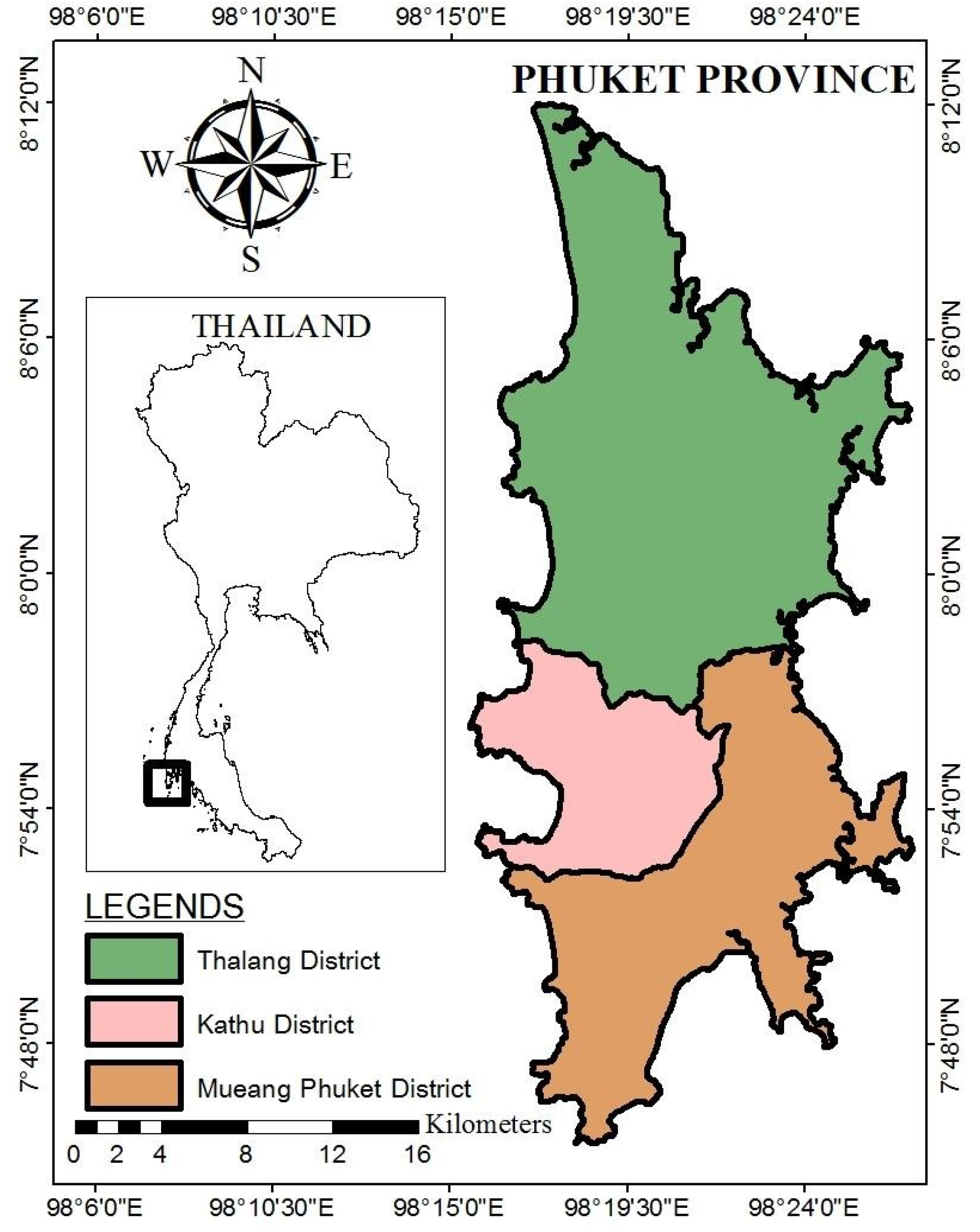

4.2. Phuket Smart City

4.3. Puket Citizen Perspectives

“We don’t have time because we have to work/study” (84%).

“We don’t understand and have no knowledge about technology” (11%).

“We are users only, it is not our responsibility, it should be leaders who take action”.

5. Discussion

Implications of This Study in the Context of Local Smart City Management

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al Awadhi, S.; Aldama-Nalda, A.; Chourabi, H.; Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Leung, S.; Mellouli, S.; Nam, T.; Pardo, A.T.; Scholl, J.H.; Walker, S. Building understanding of smart city initiatives. In International Conference on Electronic Government; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 40–53. [Google Scholar]

- Albino, V.; Berardi, U.; Dangelico, R.M. Smart cities: Definitions, dimensions, performance, and initiatives. J. Urban Technol. 2015, 22, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perboli, G.; De Marco, A.; Perfetti, F.; Marone, M. A new taxonomy of smart city projects. Transp. Res. Procedia 2014, 3, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidou, M. Smart cities: A conjuncture of four forces. Cities 2015, 47, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzguenda, I.; Alalouch, C.; Fava, N. Towards smart sustainable cities: A review of the role digital citizen participation could play in advancing social sustainability. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaroiu, G.C.; Roscia, M. Definition methodology for the smart cities model. Energy 2012, 47, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z.; Newman, P. Redefining the smart city: Culture, metabolism and governance. Smart Cities 2018, 1, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, S.; Hauerwaas, A.; Holz, V.; Wedler, P. Culture in sustainable urban development: Practices and policies for spaces of possibility and institutional innovations. City Cult. Soc. 2018, 13, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B. The Smart Enough City: Putting Technology in Its Place to Reclaim Our Urban Future; The MIT Press: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liete, E. Innovation networks for social impact: An empirical study on multi-actor collaboration in projects for smart cities. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caragliu, A.; Bo, C.; Njikamp, P. Smart cities in Europe. In Proceeding of the 3rd Central European Conference in Regional Science, Košice, Slovak Republic, 7–9 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hollands, G.R. Will the real smart city please stand up? Intelligent, progressive or entrepreneurial? City 2008, 12, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffans, A.; Horelli, L. Expanded urban planning as a vehicle for understanding and shaping smart, livable cities. J. Community Inform. 2014, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bătăgan, L. Smart cities and sustainability models. Rev. De Inform. Econ. 2011, 15, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Roche, S.; Nabian, N.; Kloeckl, K.; Ratti, C. Are ‘smart cities’ smart enough. In Proceedings of the Global Geospatial Conference 2012, Québec, QC, Canada, 14–17 May 2012; pp. 215–235. [Google Scholar]

- Kramers, A.; Hojer, M.; Lovehagen, N.; Wangel, J. Smart sustain cities- Exploring ICT solutions for reduced energy use in cities. Environ. Model. Softw. 2014, 56, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahvenniemi, H.; Huovila, A.; Pinto-Seppa, I.; Airaksinen, M. What are the differences between sustainable and smart cities? Cities 2017, 60, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toli, A.M.; Murtagh, N. The Concept of Sustainability in Smart City. Front. Built Environ. 2020, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigea, A.; Leka, A.; Panagiotopoulou, M. In search of indicators for assessing smart and sustainable cities and community performances. E-Plan. Res. 2017, 6, 43–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huovila, A.; Bosch, P.; Airaksinen, M. Comparative analysis of standardized indicators for Smart sustainable cities: What indicators and standards to use and when? Cities 2019, 89, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monfaredzadeh, T.; Berardi, U. Beneath the smart city: Dichotomy between sustainability and competitiveness. Int. J. Sustain. Build. Technol. Urban Dev. 2015, 6, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A. A critical review of selected smart city assessment tools and indicator sets. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 1269–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Kamruzzaman, M. Does smart city policy lead to sustainability of cities? Land Use Policy 2018, 73, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardi, P.; Temporelli, A. Smartainability: A Methodology for Assessing the Sustainability of the Smart City. Energy Procedia 2017, 111, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, E.P.; Hinnig, M.P.F.; Moreira da Costa, E.; Marques, J.S.; Bastos, R.C.; Yigitcanlar, T. Sustainable development of smart cities: A systematic review of the literature. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2017, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.B.; Khan, M.; Han, K. Towards sustainable smart cities: A review of trends, architectures, components, and open challenges in smart cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 38, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.M. Humane and Sustainable Smart Cities: A Personal Roadmap to Transform Your City after the Pandemic; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaprasad, A.; Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Syn, T. A Unified Definition of a Smart City. In EGOV 2017: Electronic Government; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10428, pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visvizi, A.; Troisi, O. Effective Management of the Smart City: An Outline of a Conversation. In Managing Smart Cities; Visvizi, A., Troisi, O., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Joss, S.; Cook, M.; Dayot, Y. Smart Cities: Towards a New Citizenship Regime? A Discourse Analysis of the British Smart City Standard. J. Urban Technol. 2017, 24, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joamets, K.; Chochia, A. Access to artificial intelligence for persons with disabilities: Legal and ethical questions concerning the application of trustworthy AI. Acta Balt. Hist. Philos. Sci. 2021, 9, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sǎraru, C.S. The European Groupings of Territorial Cooperation developed by administrative structures in Romania and Hungary. Acta Jurid. Hung. 2014, 55, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srebalová, M.; Peráček, T. Effective Public Administration as a Tool for Building Smart Cities: The Experience of the Slovak Republic. Laws 2022, 11, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žofčinová, V.; Čajková, A.; Král, R. Local Leader and the Labor Law Position in the Context of the Smart City Concept through the Optics of the EU. TalTech J. Eur. Stud. 2022, 12, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.R.; Selin, C.; Gano, G.; Pereira, Â.G. Citizen engagement and urban change: Three case studies of material deliberation. Cities 2012, 29, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, G.; Hiroko, K. How are citizens involved in smart cities? Analysing citizen participation in Japanese Smart communities. Inf. Polity 2016, 21, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, S.; Mazhar, M.U.; Bull, R. Citizen Engagement for Co-Creating Low Carbon Smart Cities: Practical Lessons from Nottingham City Council in the UK. Energies 2020, 13, 6615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobos, A.; Jenei, A. Citizen engagement as a learning experience. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 93, 1085–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonofski, A.; Asensio, E.S.; De Smedt, J.; Snoeck, M. Citizen Participation in Smart Cities: Evaluation Framework Proposal. In Proceedings of the IEEE 19th Conference on Business Informatics (CBI), Thessaloniki, Greece, 24–27 July 2017; pp. 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Arias, A.; Urrego-Marín, M.L.; Bran-Piedrahita, L.A. Methodological Model to Evaluate Smart City Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassileva, I.; Dahlquist, E.; Campillo, J. The citizens’ role in energy smart city development. Energy Procedia 2016, 88, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tadili, J.; Fasly, H. Citizen participation in smart cities: A survey. In Proceeding of the 4th International Conference on Smart City Applications (SCA‘19), Casablanca, Morocco, 2–4 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira Neto, J.S. Inclusive Smart Cities: Theory and Tools to Improve the Experience of People with Disabilities in Urban Spaces. Doctoral Dissertation, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lytras, M.D.; Visvizi, A. Who Uses Smart City Services and What to Make of It: Toward Interdisciplinary Smart Cities Research. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.; Chen, J.-H.; Wei, H.-H.; Su, Y.-C. Towards people-centric smart city development: Investigating the citizens’ preferences and perceptions about smart-city services in Taiwan. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 67, 102691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.Y.; Taeihagh, A. Smart City Governance in Developing Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayangsari, L.; Novani, S. Multi-stakeholder co-creation Analysis in Smart city Management: An Experience from Bandung, Indonesia. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 4, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, S.; Washizu, A. Will smart cities enhance the social capital of residents? The importance of smart neighborhood management. Cities 2021, 115, 103244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chong, Z. Smart city projects against COVID-19: Quantitative evidence from China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 70, 102897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumastuti, R.D.; Rouli, J. Smart city implementation and citizen engagement in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium of Earth, Energy, Environmental Science and Sustainable Development (JEESD 2021), Jakarta, Indonesia, 25–26 September 2021; p. 940. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.; Malek, A.J.; Hussain, Y.M.; Tahir, Z. Citizen participation in building citizen-centric smart cities. Malays. J. Soc. Space 2018, 14, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannidis, S.; Marikyan, D. Smart offices: A productivity and well-being perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 51, 102027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallicelli, M. Smart cities and digital workplace culture in the global European context: Amsterdam, London and Paris. City Cult. Soc. 2018, 12, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang-Tan, R.; Ang, S. Understanding the smart city race between Hong Kong and Singapore. Public Money Manag. 2021, 42, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Miao, Z.; Wang, C. The Experience and Enlightenment of Asian Smart City Development—A Comparative Study of China and Japan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattoni, B.; Gugliermetti, F.; Bisegna, F. A multilevel method to assess and design the renovation and integration of Smart Cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2015, 15, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpintero, M.J.; Mäkitalo, N.; Garcia-Alonso, J.; Berrocal, J.; Mikkonen, T.; Canal, C.; Murillo, M.J. From the Internet of Things to the Internet of People. IEEE Internet Comput. 2015, 19, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, M.; Passarella, A.; Das, K.S. The Internet of People (IoP): A new wave in pervasive mobile computing. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2017, 41, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.; Passarella, A. The Internet of People: A human and data-centric paradigm for the Next Generation Internet. Comput. Commun. 2018, 131, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taweesaengsakulthai, S.; Laochankham, S.; Kamnuansilpa, P.; Wongthanavasu, S. Thailand smart cities: What is the path to success? Asian Politics Policy 2019, 11, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustini, H.D.Y.M. Survey by knocking the door and response rate enhancement technique in international business research. Bus. Perspect. 2018, 16, 155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Taber, S.K. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J. The insignificance of null hypothesis significance testing. Political Res. Q. 1999, 52, 647–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MICT. Thailand MICT Policy Framework (2011–2020) ICT 2020 (In Thai), Thailand; MICT: Bangkok, Thailand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- NECTEC. Thailand Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Master Plan (2002–2006), Thailand; NECTEC: Bangkok, Thailand, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- MICT. The Second Thailand Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Master Plan (2009–2013), Thailand; MICT: Bangkok, Thailand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- MICT. (Draft) The Third Thailand Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Masterplan (2014–2018) (In Thai), Thailand; MICT: Bangkok, Thailand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Manager Online. Support City Development Co., Ltd. Group for Smart City Development [In Thai]. 2017. Available online: http://www.manager.co.th/ (accessed on 1 April 2017).

- PPO. Operational Plan of Phuket Smart City (2018–2021) (In Thai), Group of Strategy and Information for Province Development, Thailand. 2016. Available online: https//www.phuket.go.th/webpk/contents.php?str=plan (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- DEPA. SIPA Announced 4 Projects of SIPA for SMEs Development [In Thai]. 2015. Available online: http://mict.go.th/view (accessed on 5 April 2017).

- Wetprasit, R.; Nanthaamornphong, A. Phuket smart city and the needs of its population [In Thai]. In Proceedings of the 12th National Conference on Computing and Information Technology (NCCIT 2016), Khon Kaen, Thailand, 7–8 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- SIPA. Phuket Smart City. 2015. Available online: http://www.phuket.go.th/ (accessed on 16 April 2016).

- Dupont, L.; Morel, L.; Guidat, C. Innovative public-private partnership to support Smart City: The case of “Chaire REVES”. J. Strategy Manag. 2015, 8, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, E.; Kleinhans, R. Beyond technology: Identifying local government challenges for using digital platforms for citizen engagement. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 40, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masucci, M.; Pearsall, H.; Wiig, A. The Smart City Conundrum for Social Justice: Youth Perspectives on Digital Technologies and Urban Transformations. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2019, 110, 476–484. [Google Scholar]

- Rexhepi, A.; Filiposka, S.; Trajkovik, V. Youth e-participation as a pillar of sustainable societies. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chan, H.S.A. Gerontechnology acceptance by elderly Hong Kong Chinese: A senior technology acceptance model (STAM). Ergonomics 2014, 57, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chan, H.S.A. Predictors of gerontechnology acceptance by older Hong Kong Chinese. Technovation 2014, 34, 126135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitlin, D. With and beyond the state—Co-production as a route to political influence, power and transformation for grassroots organizations. Environ. Urban. 2008, 20, 339–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.K.; Devarajan, S.; Khemani, S.; Shah, S. Decentralization and Service Delivery; World Bank Policy Research Working; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Volume 3603. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, T.T.G.; Dupont, L.; Camarg, M. Application of Decision-Making Methods in Smart City Projects: A Systematic Literature Review. Smart Cities 2019, 2, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SIPA’s PSC Road Map | PPO’s PSC Themes | PPO’s PSC Vision |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Smart city collaboration 2. Investment left 3. Startup ecosystem 4. Digital content branding to overseas market | 1. Smart economy | Hub of creative entrepreneurs |

| 5. International creative and innovation entrepreneur academy | 2. Smart education | Smart learning community |

| 6. Smart living community | 3. Smart environment | Phuket green city |

| 4. Smart government | Smart and sustainable Phuket | |

| 5. Smart healthcare | Smart hospital and patient single ID | |

| 6. Smart safety | Phuket safe city (CCTV and Maritime) | |

| 7. Smart tourism | Tourism digital economy model |

| Heard about Phuket Smart City? | Yes (n = 184) | No (n = 225) | Total (n = 409) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 1. Districts | X2 (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Mueang District | 132 | 72 | 117 | 52 | 249 | 61 |

| Thalang District | 42 | 23 | 62 | 28 | 104 | 25 |

| Kathu District | 10 | 5 | 46 | 20 | 56 | 14 |

| 2. Gender | X2 (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Male | 84 | 46 | 64 | 28 | 148 | 36 |

| Female | 100 | 54 | 161 | 72 | 261 | 64 |

| 3. Age (years) | X2 (p = 0.013) | |||||

| <21 | 10 | 5.4 | 33 | 15 | 43 | 11 |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 21–40 | 112 | 61 | 134 | 59 | 246 | 60 |

| 41–60 | 52 | 28.2 | 51 | 23 | 103 | 25 |

| >60 | 10 | 5.4 | 7 | 3 | 17 | 4 |

| 4. Birth place | X2 (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Phuket | 110 | 60 | 91 | 40 | 201 | 49 |

| Other provinces (Answer question 5) | 75 | 41 | 133 | 59 | 208 | 51 |

| 5. Length of stay (years) For non-natives | X2 (p = 0.091) | |||||

| <1 | 5 | 7 | 19 | 14 | 24 | 11 |

| 1–5 | 22 | 29 | 54 | 41 | 76 | 36 |

| 6–10 | 19 | 25 | 28 | 21 | 47 | 23 |

| 11–15 | 14 | 19 | 13 | 10 | 27 | 13 |

| 16–20 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 8 | 18 | 9 |

| >20 | 8 | 11 | 8 | 6 | 16 | 8 |

| 6. Education | X2 (p < 0.001) | |||||

| <Senior high school | 6 | 3 | 37 | 16 | 43 | 10 |

| Senior high school | 21 | 11 | 61 | 27 | 82 | 20 |

| Diploma | 13 | 7 | 18 | 8 | 31 | 8 |

| Bachelor degree | 112 | 61 | 103 | 46 | 215 | 53 |

| >Bachelor degree | 32 | 18 | 6 | 3 | 38 | 9 |

| 7. Monthly income (THB) | X2 (p < 0.001) | |||||

| <10,000 | 19 | 10 | 50 | 22 | 69 | 17 |

| 10,000–20,000 | 53 | 29 | 101 | 45 | 154 | 38 |

| 20,001–30,000 | 48 | 26 | 40 | 18 | 88 | 21 |

| >30,000 | 64 | 35 | 35 | 15 | 99 | 24 |

| 8. Occupation | X2 (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Government | 15 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 20 | 5 |

| Heard about Phuket Smart City? | Yes (n = 184) | No (n = 225) | Total (n = 409) | |||

| Private | 40 | 22 | 38 | 17 | 78 | 19 |

| Personal business | 67 | 37 | 49 | 22 | 116 | 28 |

| Merchants | 19 | 10 | 49 | 22 | 68 | 17 |

| Freelance | 21 | 11 | 52 | 23 | 73 | 18 |

| Student | 15 | 8 | 30 | 13 | 45 | 11 |

| Others | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 2 |

| 9. Community position | X2 (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Leader/Local government | 14 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 4 |

| Community member | 170 | 92 | 225 | 100 | 395 | 96 |

| 10. Will participate in Phuket Smart City? | X2 (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Yes | 140 | 76 | 88 | 39 | 228 | 56 |

| No | 44 | 24 | 137 | 61 | 181 | 44 |

| Will Participate in Phuket Smart City? | Yes (n = 228) | No (n = 181) | Total (n = 409) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 1. Districts | X2 (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Mueang District | 166 | 73 | 83 | 46 | 249 | 61 |

| Thalang District | 44 | 19 | 60 | 33 | 104 | 25 |

| Kathu District | 18 | 8 | 38 | 21 | 56 | 14 |

| 2. Gender | X2 (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Male | 100 | 44 | 48 | 27 | 148 | 36 |

| Female | 128 | 56 | 133 | 73 | 261 | 64 |

| 3. Age (Years) | X2 (p = 0.11) | |||||

| <21 | 19 | 8 | 24 | 13 | 43 | 11 |

| Will participate in Phuket smart city? | Yes (n = 228) | No (n = 181) | Total (n = 409) | |||

| 21–40 | 143 | 63 | 103 | 57 | 246 | 60 |

| 41–60 | 60 | 26 | 43 | 24 | 103 | 25 |

| >60 | 6 | 3 | 11 | 6 | 17 | 4 |

| 4. Birth place | X2 (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Phuket | 130 | 57 | 71 | 39 | 201 | 49 |

| Other provinces (Answer question 5) | 98 | 43 | 110 | 61 | 208 | 51 |

| 5. Length of stay (Years) For non-natives | X2 (p = 0.48) | |||||

| <1 | 11 | 11 | 14 | 13 | 25 | 12 |

| 1–5 | 33 | 34 | 45 | 41 | 78 | 37 |

| 6–10 | 27 | 28 | 20 | 18 | 47 | 23 |

| 11–15 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 27 | 13 |

| 16–20 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 18 | 9 |

| >20 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 8 | 13 | 6 |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 6. Education | X2 (p < 0.001) | |||||

| <Senior high school | 11 | 5 | 32 | 18 | 43 | 10 |

| Senior high school | 34 | 15 | 48 | 26 | 82 | 20 |

| Diploma | 17 | 7 | 14 | 8 | 31 | 8 |

| Bachelor degree | 138 | 61 | 77 | 42 | 215 | 53 |

| >Bachelor degree | 28 | 12 | 10 | 6 | 38 | 9 |

| 7. Monthly income (THB) | X2 (p < 0.001) | |||||

| <10,000 | 28 | 12 | 40 | 22 | 68 | 17 |

| 10,000–20,000 | 76 | 33 | 78 | 43 | 154 | 38 |

| 20,001–30,000 | 52 | 23 | 36 | 20 | 88 | 21 |

| >30,000 | 72 | 32 | 27 | 15 | 99 | 24 |

| 8. Occupation | X2 (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Government | 12 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 20 | 5 |

| Private | 58 | 25 | 20 | 11 | 78 | 19 |

| Personal business | 79 | 35 | 37 | 20 | 116 | 28 |

| Merchants | 23 | 10 | 45 | 25 | 68 | 17 |

| Freelance | 30 | 13 | 43 | 24 | 73 | 18 |

| Student | 22 | 10 | 23 | 13 | 45 | 11 |

| Others | 4 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 9 | 2 |

| 9. Community position | X2 (p = 0.004) | |||||

| Leader/Local government | 13 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 14 | 3 |

| Community member | 215 | 94 | 180 | 99 | 395 | 97 |

| 10. Heard about Phuket Smart City? | X2 (p < 0.001) | |||||

| Yes | 140 | 61 | 44 | 24 | 184 | 45 |

| No | 88 | 39 | 137 | 76 | 225 | 55 |

| Questions | No. of People (n = 409) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Willingness to participate in PSC stages | 228 | 56 |

| 1.1 Cause of problem and solution | 99 | 43 |

| 1.2 Planning and action | 73 | 32 |

| 1.3 Investment | 40 | 18 |

| 1.4 Monitoring and evaluation | 16 | 7 |

| Unwillingness | 181 | 44 |

| Participation interest in PSC dimensions | ||

| Economy | 119 | 29 |

| Education | 62 | 15 |

| Security | 61 | 15 |

| Environment | 58 | 14 |

| Tourism | 54 | 13 |

| Governance | 42 | 11 |

| Public health | 13 | 3 |

| Questions | No. of people (n = 409) | Percentage (%) |

| Purpose of internet use in daily life | ||

| Reading news and socializing | 276 | 68 |

| Operating businesses | 58 | 14 |

| Searching for information | 55 | 13 |

| Others (Entrepreneurship, System Developer, ICT Producer) | 12 | 3 |

| N/A | 8 | 2 |

| Preferred communication channel for PSC information | ||

| 243 | 60 | |

| LINE application | 50 | 12 |

| Mobile application | 41 | 10 |

| Website | 39 | 9 |

| Meeting | 29 | 7 |

| N/A | 7 | 2 |

| PSC Projects | Open Suggestions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topic | Word of Frequency | No. of People (n = 146) | % | Topic | Word of Frequency | No. of People (n = 98) | % |

| Development | 61 | 49 | 34 | Development | 32 | 30 | 31 |

| Management | 52 | 47 | 32 | Management | 28 | 22 | 22 |

| Education | 44 | 41 | 28 | Public | 25 | 23 | 23 |

| Tourism | 43 | 38 | 26 | Transportation ** | 15 | 14 | 14 |

| System * | 31 | 20 | 14 | Tourism | 15 | 13 | 13 |

| Tourist * | 28 | 24 | 16 | Traffic ** | 14 | 13 | 13 |

| Economic * | 26 | 26 | 18 | Government | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Waste * | 22 | 19 | 13 | City ** | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Public | 20 | 20 | 14 | Smart ** | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Government | 19 | 21 | 14 | Environment ** | 9 | 8 | 8 |

| Education | 8 | 8 | 8 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sontiwanich, P.; Boonchai, C.; Beeton, R.J.S. An Unsustainable Smart City: Lessons from Uneven Citizen Education and Engagement in Thailand. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013315

Sontiwanich P, Boonchai C, Beeton RJS. An Unsustainable Smart City: Lessons from Uneven Citizen Education and Engagement in Thailand. Sustainability. 2022; 14(20):13315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013315

Chicago/Turabian StyleSontiwanich, Phanaranan, Chantinee Boonchai, and Robert J. S. Beeton. 2022. "An Unsustainable Smart City: Lessons from Uneven Citizen Education and Engagement in Thailand" Sustainability 14, no. 20: 13315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013315

APA StyleSontiwanich, P., Boonchai, C., & Beeton, R. J. S. (2022). An Unsustainable Smart City: Lessons from Uneven Citizen Education and Engagement in Thailand. Sustainability, 14(20), 13315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013315