Abstract

The aim of this study was to analyze the role of the state in managing the Polish market of agricultural property through the introduced legal regulations. The analysis was based on declarations of intent to exercise pre-emptive rights to agricultural property that were issued in the province of Warmia and Mazury between 2016 and 31 December 2021. Legal regulations aiming to restrict the purchase of the agricultural property of the State Treasury Reserve (STR) in particular by foreign buyers came into force in 2016. At present, the main task of the National Support Center for Agriculture (Polish acronym: KOWR) is to purchase and repurchase agricultural property from private owners (pre-emptive right and the right of purchase). KOWR exercises its pre-emptive right to agricultural property before it is offered to other buyers, and it is entitled to purchase that property on the conditions specified by the parties to the agreement and for the agreed price. The research results justify the conclusion that the Polish state’s interventionism in the sale of agricultural land has an impact on the shape of the agricultural system in Poland.

1. Introduction

The agricultural system in Poland has been shaped for a very long time, and the legacy of the enfranchisement reforms is of particularly great importance in the development of the countryside and farming. The legal regulations shaping the agricultural system play an important role in the economic and political spheres. The normative framework created by the legislator which governs property relations in agriculture has a direct influence on this economic sector’s real production potential and, by extension, on the living standard of the rural population.

The agricultural system is a set of property relations and organizational forms of production in agriculture. It follows from Article 23 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland [1] that the agricultural system perceived as above is a special element of the state’s socio-economic system, understood as ”material conditions for social life, ownership structure and the functioning of the public finance economy.“ In addition to the provisions of Article 20, which define the foundation of the economic system, Article 23 specifies that a family farm shall be the basis of the agricultural system in Poland [2,3].

The PWN Encyclopedia [4] defines the agricultural system as a socio-political system, as well as the type of ownership of basic production means (mainly land) and their use in agriculture, as well as resultant social relationships between different groups of rural and urban communities. According to Wilkin [5], the agricultural system represents the institutional framework under which agriculture operates and develops, and which consists of:

- -

- The ownership of land and other production means in agriculture;

- -

- A normatively defined scope and forms of state interventionism in agriculture, including the regulation of the agricultural market and public agencies established for this purpose;

- -

- Organizational and legal forms of agricultural activity as well as links between agriculture and other elements of the state and economy;

- -

- The scope and forms of self-organization of farmers.

During the interwar years and immediately after World War Two, as well as a few decades later during the post-socialism transformation in Poland, there were several political and economic programs which addressed the interest of small farmers and the landless rural population. The aim of these programs was to gain the support of peasants and the rural proletariat for the system, institutional transformations, and the new authorities. In consequence, the post-war agricultural reforms changed the structure of farms, causing land fragmentation and an increase in the number of small and very small farms [6]. Jurcewicz [7], who analyzed the evolution of the legal regulations concerning agricultural land management in 1944–1984, concluded that the basic premise of the agricultural policy in that period was the belief that communal ownership of property was superior to privately owned means of production. It was not until 1980 that a fundamental change in political directives can be said to have taken place. It was then acknowledged that family farms in agriculture were a permanent and equal element in the socio-economic system of the Polish People’s Republic.

The beginning of state institutions involved in the management of the state-owned agricultural property after the state transformation in Poland dates back to 1992. The Polish government’s approach to the distribution of the agricultural property of the State Treasury Reserve (STR) has evolved over the years. Initially, the most popular form of distribution was land leases [8,9,10]. Poland’s access to the EU arose much interest in the purchase of agricultural property (largely among people not involved in farming). From 2004 to 2016, the year-average prices paid for agricultural land showed a distinctly increasing tendency, although it is worth emphasizing that the turnover of farmland on the private market was limited. This trend manifested itself in all groups of land area size and in all regions of Poland. Until 2016, the main task of the Agricultural Property Agency (ANR) was to privatize the State Treasury property in the ways stipulated in the Act on the Management of the State Treasury property. The privatization of farmland was aimed at improving the agrarian structure. Prior to accessing the European Union on 1 May 2004, Poland had negotiated a twelve-year-long transition period in terms of the acquisition of real estate property by foreigners. New legal regulations entered into force in order to prevent the purchase of land by persons who were not citizens of Poland.

On 30 April 2016, a further act came into force, the Act on the Suspension of the Sale of the Agricultural Property from the State Treasury and on the Amendments of Certain Acts (Official Journal of 2016, item 585), which amended the Act on the Shaping of the Agricultural System of 11 April 2003 (Official Journal of 2012, item 803 with subsequent amendments). It follows from the legislator’s assumptions that the principal objective of the new regulations was to strengthen the protection of agricultural land from speculative purchase by domestic and foreign entities (both natural and legal persons), as well as to halt the undesirable trend in the agrarian system, and to improve the economic status of Polish farmers. The mentioned act was also expected to guarantee real protection of Polish land from the uncontrolled buyout.

As a consequence, the prices decreased in 2017–2018 (by 4% in 2017 relative to 2016 and by 15% in 2018 relative to 2017). In consecutive years, prices began to increase, by 17% in 2019 and 14% in 2020 [10,11,12].

Pursuant to the new legal regulations, the lease has become the basic approach to the management of state farmland. It was the legislator’s intention to create solutions beneficial to farmers (lease as the least expensive way of securing more farmland). The lease contracts are supposed to be drawn up for long term, up to 10 years, which should assist private farmers in planning their on-farm production rationally. Currently, one of the major tasks performed by KOWR is to purchase and repurchase agricultural real estate (pre-emptive right and the right of purchase), that is to express the declaration of intent to exercise the pre-emptive right and the right to purchase agricultural properties. This is one of the ways of building the state land capital in Poland KOWR, which is expected to contribute to the future development of family owned farms.

The foundation of the agricultural system in Poland is the family farm, which is defined in Art. 5.1 of the Act on the Shaping of Agricultural System [13], of 11 April 2003 (Official Journal of 2022, item 461) [14]. Pursuant to this law, the family farm is an agricultural farm run by an individual farmer, in which the total area of farmland does not exceed 300 ha. Furthermore, a farm is defined in Polish law in some legal regulations, including:

- -

- Agricultural land inclusive of woodland, buildings or their parts, facilities and livestock, as long as they constitute or can constitute an organized economic entity, as well as the legal regulations pertaining to the management of an agricultural farm (Official Journal of 2002, item 1360);

- -

- Agricultural land inclusive of woodland, buildings or their parts, equipment and livestock, if they constitute or can constitute an organized economic entity as well as the rights pertaining to the running of an agricultural farm (Art. 533 of the Act of 23 April 1964 and Civil Code [15];

- -

- The area of land classified in the register of land and buildings as agricultural land, excluding the land occupied by business activity other than agricultural activity, with the total surface area exceeding 1 ha or 1 convertible ha, owned or possessed by a natural person, legal person, or an organization, including a company, not being a legal person (Art. 2 of the Act on Agricultural Tax [16]);

- -

- An agricultural farm as specified in the Civil Code, with an area of no less than 1 ha of farmland (Art. 2 of the Act on the Agricultural System [13]).

Family farms play an important role in the European countryside [17], but it is worth emphasizing that a family farm is also a key contributor to global food production [18,19]. Family farms make up over 98% of all agricultural farms and occupy 53% of the total farmland area [18]. However, as Darnhofer et al. [17] demonstrated in their study, the number of family farms is constantly decreasing. The data from the latest Agricultural Census in Poland, conducted in 2020, revealed a decreasing tendency in the number of family farms lasting for many years, which was accompanied by a relatively small increase in their average surface area, from 9.8 ha of utilized agricultural area (UAA) in 2010 to 11.1 ha UAA in 2020. Under the current economic conditions, an area of 50 ha seems to be the lower threshold of the size of a farm, below which cultivation of typical crops generates such low revenues that it is difficult to achieve at least a parity income and most often prohibit further investment. Hence, an area of 50 ha UAA is also considered to be the minimum area of a farm where modern production technologies, e.g., precision agriculture, are economically viable. Regardless of the ongoing changes, farms with an area of over 50 ha UAA in Poland cover the total farmland of 5 million hectares UAA, which is merely 35% of all UAA. In terms of the share of farms larger than 50 ha in all farms, the Polish agriculture ranks close to the last place among all EU member states [20].

A family farm is understood as a farm which provides for the maintenance of the farmer’s family [21]. Thus, it cannot be too small. Its size must be suitable, too, to ensure sufficient physical labor for its owner and the owner’s family with the help of hired labor, if necessary. Another significant aspect is the farm’s technological capacity and equipment [22]. Family farms should be defined qualitatively, and the main indicators are the life of a farmer’s family and the considerable labor input [23]. The attitude towards running a family farm is changing. Family farms fit the policy of pluriactive development. Pluriactivity is not just a way for uneconomic farms to survive but also an option to increase revenues. The adaptability and productivity demonstrated by family farm owners persist [23,24,25], but support measures offered by the state are needed in the face of changing social, economic, and geopolitical circumstances.

In the early years after Poland’s accession to the European Union, the situation on the agricultural market and the Common Agricultural Policy promoted economically strong farms to strengthen their position in the agricultural market and increase their size [26]. The main outcome was the progressive polarization of the area structure of individual farms, which was manifested by the increasing percentage of both relatively small and large farms [26,27].

Agricultural land may have many values and functions for different buyers at the same time [28]. Therefore, it seems important to define the potential buyer, as this is the factor that largely decides about transaction prices of agricultural properties. Quite often, agricultural properties are purchased with a view of alternative future development, other than for farming or forestry. This mostly concerns agricultural real estate located conveniently in relation to large cities, with good accessibility or high landscape value [11,29,30].

The research objective is to reveal the scale of the Polish state’s interventionism consisting of exercising statutory rights such as the right of pre-emption and the right of purchase, as well as changes in the approach to the handling of real estate which belongs to the State Treasury Agricultural Property Resource (for short: State Treasury Reserve (STR)). In addition, an attempt was made to determine the effect of the binding law on the agricultural land market in Poland. The analyses were based on declarations of intent to exercise the pre-emptive right and the right to acquire land, both being significant tasks delegated in 2016 to the KOWR Territorial Branches. A declaration of intent is regulated in the Code of Civil Law and stands for a situation when a specific person expresses their will in order to cause certain legal consequences (that is consequences of activities altering the legal status). Hence, the time period submitted to analyses spanned a period from 2016 to 2021. The territorial scope of the study covered the province of Warmia and Mazury. Based on the research results, it is evident that the Polish state’s interventionism in the sale of agricultural land has an impact on the shaping of the agricultural system in Poland.

2. Materials and Methods

From 1992, when the State Treasury Agricultural Property (the Polish acronym: WRSP) was established, until the end of 2021, 4754.8 thousand hectares in total were incorporated into its reserve. Most of the agricultural real estate properties included in the State Treasury Agricultural Property Resource (STR) lie in the northern and western parts of Poland. Currently, most land transferred to the STR, which amounts to 824.72 thousand ha, is in the province of Warmia and Mazury. The agricultural land owned by the State Treasury and situated in this Polish province is managed by the Branch Office (BO) of the National Support Center for Agriculture (KOWR) in Olsztyn. This BO is also the most active one among all branch offices of KOWR in terms of distributing the farmland from the State Treasury Agricultural Property Resource and, more recently, purchasing land for the STR. These are two reasons why the province of Warmia and Mazury was selected for our detailed analyses of the current conditions underlying the management of the State Treasury Agricultural Property Resource and the shaping of the agricultural system in Poland.

Basic terms associated with agricultural space include utilized agricultural area, agricultural land, agricultural real estate, and agricultural holding. Each is defined in different laws because each refers to different segments of the space and consequently denotes different items. Considering the purpose of this study, it is pertinent to define agricultural real estate, which is the subject of this research and a component of an agricultural holding, including family farms.

Pursuant to Article 46 of the Civil Code of 23 April 1964, agricultural real estate (agricultural land) comprises immovable properties which are or can be used for conducting agricultural activity in the scope of plant and animal production, not excluding horticultural production, vegetable production, and fish production [15]. The agricultural real estate belongs to so-called non-urbanized properties, mostly situated in rural areas.

A narrower definition of agricultural real estate is provided by the Act on the Shaping of the Agricultural System of 11 April 2003 [13]. According to this law, agricultural real estate is an agricultural property within the meaning of the Civil Code, excluding properties situated in areas designated other than agricultural functions in local spatial management plans.

2.1. Characteristics of the Province of Warmia and Mazury Related to the Research Scope

The province of Warmia and Mazury is distinguished among other Polish provinces by the share of rural areas in the total area. This percentage in Warmia and Mazury is the highest in Poland at 97.4%, whereas Poland’s average value is 92.9%. Compared with the year 2004, the contribution of rural areas to the province’s total area has decreased slightly. However, similar tendencies have been detected in most Polish regions. The province of Warmia and Mazury is characterized by the high degree of utilization of land for agricultural purposes. The total area of agricultural land in 2020 in this region was 1379.4 thousand ha. In this respect, the province occupied the fourth place in the country.

The region compares positively to the whole country in terms of the reserve of agricultural land per farm. This is the consequence of both a large area size of an average farm and a small number of farms relative to the country’s average. In 2016, there were 43.5 thousand operating agricultural farms, which corresponded to 3.08% of the total number of Polish farms. In 2016, an average farm in Warmia and Mazury was the size of 26.19 ha, including 23.7 ha of utilized agricultural area.

The quality of soils in the province is approximately the same as the country’s average. Soils with medium utilizable quality (class IV in the Polish soil valuation system) cover around 51.5% of agricultural land. Soils with high quality (classes I, II, and III) cover only around 23% of agricultural land, while those of low quality, approximately 25.5%. Soils with the highest quality for agricultural production, which are the fundamental soil pool for commodity agriculture, are found in the northern belt of the region. What distinguishes the region of Warmia and Mazury from other parts of Poland is the occurrence of fluvisols, which stretch over a vast area in Żuławy along the Vistula River. Despite their defective properties caused by the hydrogeological relations, these soils are one of the most fertile types of soils in Poland. Within the province of Warmia and Mazury, there are territories with diverse soil water relations and different needs for drainage. The area of Żuławy, mentioned above, requires continuous drainage works to maintain the optimal level of groundwater [31,32].

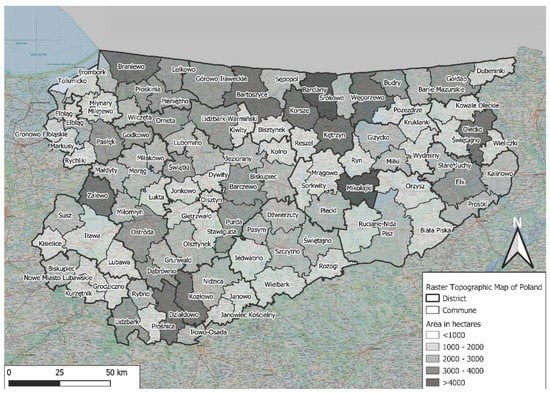

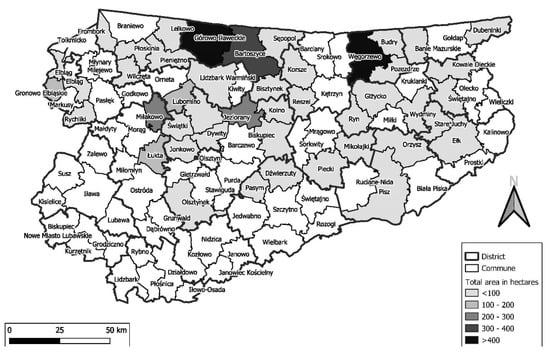

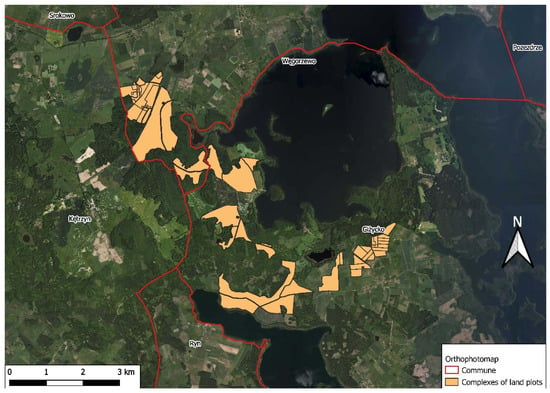

The scope of the study covers intervention activities carried out by the National Center for Agricultural Support (KOWR), consisting of KOWR exercising its pre-emptive right and the right to purchase agricultural land for the State Treasury Agricultural Property Resource (STR), henceforth referred to as declarations of intent, pursuant to the Act on Shaping the Agricultural System (henceforth referred to as the ukur Act). Figure 1 displays the area of the research (province of Warmia and Mazury) on a topographic map, including the current administrative division of the state, that is the borders of districts and municipalities, and indicating the location of the agricultural land included in the State Treasury Agricultural Property Resource (as of 31 December 2021). The analyses were based on declarations of intent (compliant with the ukur Act) in relation to each municipality, which is the smallest unit of Poland’s administrative division.

Figure 1.

Area of undeveloped agricultural land contained in the State Treasury Agricultural Property Resource in the province of Warmia and Mazury, including the administrative division into municipalities (as of 31 December 2021).

2.2. Data and Sources of Data

Following the liquidation of State Agricultural Farms in Poland, a central institution was established to ensure that state-owned agricultural property is managed rationally. The first central institutions responsible for the management of state-owned agricultural properties following the state system transformation in Poland were established in 1992. At present, this is the responsibility of the National Support Center for Agriculture (Polish acronym: KOWR).

The source materials used in this study originated from a database contained in the annual reports issued by the National Support Center for Agriculture on the operations of KOWR in the years 2016–2021. Furthermore, detailed information about the execution of the pre-emptive right and right to purchase was obtained from notarial deeds made available by KOWR. A comparative method was applied to review the collected data in order to visualize the scale of the investigated problem, with special emphasis laid on the number of concluded transactions, area of the land purchased to the STR, and achieved transaction prices. The objective was to determine certain relations, such as the effect of environmental assets, pressure of residential areas (i.e., distance from larger urban centers), or attractiveness for tourism and other types of investment attractiveness (e.g., services or industry). The research results illustrate the current tendencies in terms of the number and structure of purchased parcels of agricultural land and pre-emptive rights performed, described against the background of the overall agricultural land trade in Poland. The case study presented in this paper deals with the agricultural properties bought by KOWR and added to the State Treasury Agricultural Property Resource, which reached very high transaction prices over the analyzed time period.

The study proceeded through the following stages:

- Identification of the research subject and selection of the research area;

- Perusal of the literature: collecting source information and creating a database composed of a number of declarations of intent to exercise the pre-emptive right and the right to purchase an agricultural real estate property for the State Treasury Agricultural Property Resource;

- An analysis of the scale of the acquisition of farmland through declarations of intent to exercise the right of pre-emptive and the right to purchase a property for the STR in Poland in 2016–2021;

- Conclusions.

Until 2016, there had been immense interest in the purchase of agricultural land by entities outside the agricultural sector. At present, the government’s efforts and binding law limit the purchase of agricultural land by persons not connected with agriculture. For this reason the following research hypotheses were put forth:

Hypothesis 1.

The Polish government’s intervention policy contributes to the discontinuation of adverse functional changes in rural areas and the limitation of using agricultural land for non-agricultural purposes.

Hypothesis 2.

The measures taken by KOWR support the development of family farms in Poland.

For the purposes of this study, the concept of adverse functional changes in agricultural areas was defined. It is understood as restricting the use of agricultural land, especially agricultural land endowed with high productive values, in favor of other purposes not connected with agriculture. Such agricultural land is often characterized by high natural and landscape qualities. In view of the above, plots of agricultural land may be attractive for developing recreational or housing functions or else they may have some other investment potential.

3. Results

In Poland, the agricultural real estate market consists of a state and a private market, the latter is also referred to as a local or neighbor market. Of significance are transactions concerning the agricultural land from the State Treasury Reserve, which is composed of the land from the former State Land Fund (the Polish acronym: PFZ) and the land from dissolved State Agricultural Farms (the Polish acronym: PGR) [8]. After 1989, the state agencies (currently, KOWR) have taken over 4 million 740 thousand hectares of such farmland, of which over 1.1 m ha remains leased to farmers.

Most of the real estate from the State Treasury Agricultural Property Reserve is distributed for agricultural purposes. The agricultural properties, which make up a large share in the STR, are first of all allocated to private farmers who intend to enlarge their family run farms, or to persons who have agricultural qualifications and wish to start a family farm.

The Polish government’s approach to the distribution of the agricultural property of the State Treasury Reserve (STR) has evolved over the years. Initially, agricultural property was distributed mostly under lease agreements, but the demand for agricultural land increased substantially among private buyers (including non-farmers) after Poland joined the European Union. The legal regulations contained in the Act on the Shaping of the Agricultural System, [13], hereinafter referred to as the ukur Act, are among the essential components of the state’s agricultural policy. The preamble to the above act states that the implementation of the state’s agricultural policy aims to strengthen the protection and development of family farms, to ensure proper management of agricultural land in Poland, and to support sustainable agriculture, carried out in line with the environmental protection requirements and good agricultural practice. In compliance with the provisions of the ukur Act, KOWR can also buy agricultural property in the private market and then add it to the State Treasury Agricultural Property Reserve.

Whenever an agricultural property is for sale, the National Support Center for Agriculture (KOWR) has the pre-emptive right to this property. Furthermore, KOWR has the right to purchase an agricultural property if its acquisition takes place as a result of:

- The conclusion of a contract other than a sales contract, or;

- A unilateral legal act, or;

- A decision of a court of law or a public administration body or a decision of a court or an enforcement authority issued pursuant to the provisions of enforcement proceedings, or;

- Another legal act or event (including acquisitive prescription, inheritance, division, transformation, or merger of commercial companies).

The scale of this phenomenon since the mentioned law entered into force in Poland is demonstrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

The pre-emption right to agricultural real estate to which the state institutions ANR/KOWR are entitled.

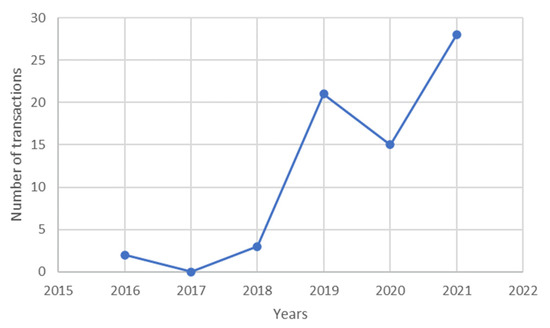

The above rights (i.e., pre-emptive right and the right to purchase) mean that in the cases specified in the ukur Act, KOWR has the right to ‘enter’ in place of the buyer and buy the property on the terms specified (including the ones agreed upon by the parties to the contract) with the payment of the price of the agricultural property in question. The National Support Center for Agriculture (KOWR) can exercise the right of pre-emptive and the right to purchase (i.e., submit a declaration of intent to purchase a given agricultural property) within a month of the receipt of a conditional sale agreement or adequate notification. It needs to be underlined that pre-emptive transactions were prevalent during the analyzed time period and in the area selected for the research, i.e., the province of Warmia and Mazury. In 2020, for example, only one notarial deed resulting from a declaration of the intent to make a purchase and concerning an agricultural property of an area of 3.9524 ha was performed. In total, from May 2016 until the end of October 2021, the Olsztyn Branch Office of KOWR purchased 66 real estate properties by exercising the pre-emptive right and right to purchase, including two transactions in 2016, three transactions in 2018, 21 transactions in 2019, 15 transactions in 2020, and 25 transactions in 2021. This is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Number of transactions arising from declarations of intent pursuant to the ukur Act in the province of Warmia and Mazury.

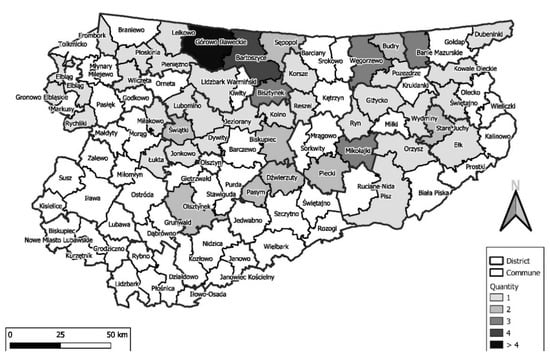

Considering the spatial distribution, most transactions during the analyzed time were concluded in the northern part of the province, especially in the municipality Górowo Iławeckie (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Number of transactions arising from declarations of intent pursuant to the ukur Act in all municipalities of the province of Warmia and Mazury.

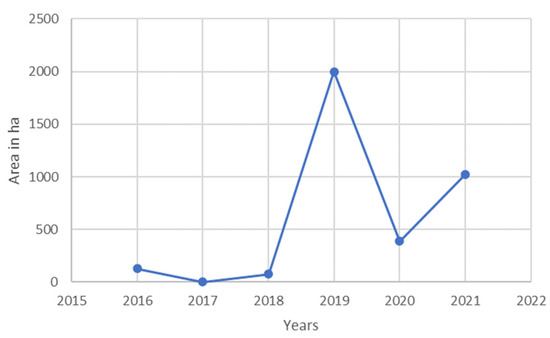

Regarding the amount of land bought following the submission of a declaration of intent, pursuant to the ukur Act, most land was purchased for the State Treasury Agricultural Property Reserve in 2019, when it totaled 2000 ha of farmland (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Area of agricultural land bought following the submission of a declaration of intent pursuant to the ukur Act in the province of Warmia and Mazury.

Most areas of agricultural land were bought for the Reserve in the municipalities of Górowo Iławeckie, Węgorzewo, and Bartoszyce, which is in the northern part of the region which, as mentioned earlier, also stood out in terms of the number of transactions (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Area of the agricultural properties purchased on submission of a declaration of intent pursuant to the ukur Act in the municipalities of the province of Warmia and Mazury.

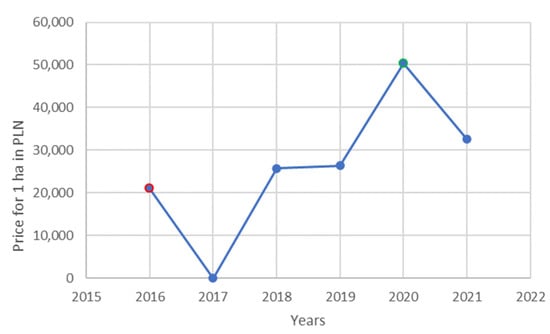

The lowest average transaction prices for 1 ha of land were achieved in 2020, when they approximated 50,000 PLN/ha, i.e., around 11,000 EUR/ha. This is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Average transaction prices for 1 ha of agricultural land purchased for the Reserve on submission of a declaration of intent pursuant to the ukur Act in the province of Warmia and Mazury.

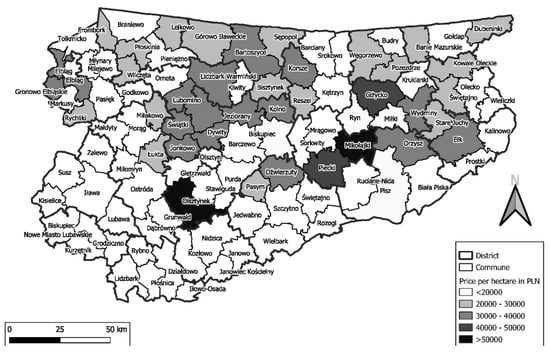

Regarding the spatial distribution of the municipalities in the province of Warmia and Mazury, the highest transaction prices occurred in the central-western part of the region, i.e., in the municipalities of Olsztynek, Mikołajki, Giżycko, and Piecki (Figure 7). There, the average transaction prices approximated 50,000 PLN/ha (around 11,000 EUR/ha).

Figure 7.

Average price of 1 ha of the agricultural land bought for the STR on submission of a declaration of intent pursuant to the ukur Act in the municipalities of the province of Warmia and Mazury.

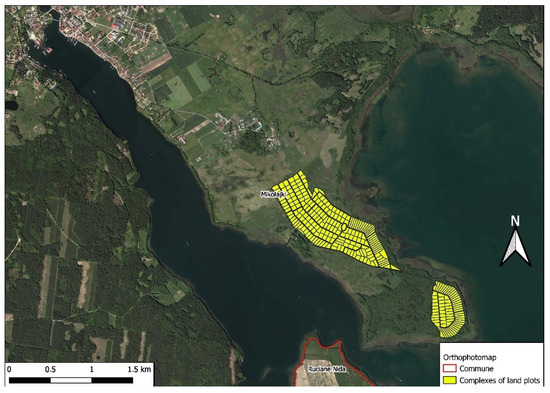

Noteworthy are some extreme transactions with excessively low or high transaction prices. In 2020, there were three transactions where the price was around 120,000 PLN/ha, that is 26 700 EUR/ha. What distinguished all these three properties were the very good location in immediate proximity to the Great Masurian Lakes. Moreover, they were all endowed with uniquely high natural and landscape values. Additionally, when the KOWR Branch Office in Olsztyn exercised its pre-emptive right to buy these properties, they were in the process of transformation to non-agricultural land use. Later, each was divided into plots of around 3000 m2, which in Polish law is the smallest area allowed when dividing an agricultural property (Figure 8). This situation raises doubt as to the extent of the state’s interventionism in shaping the agricultural system. Would it not be better if the state authority, such as KOWR, bought real estate properties with an obvious potential for farming, which is characterized by much lower transaction prices?

Figure 8.

A real estate property bought at the highest transaction price per 1 ha by the Olsztyn Branch Office of KOWR through the submission of a declaration of intent.

There was also a transaction concluded in the province of Warmia and Mazury for a very low price of about 8100 PLN/ha, i.e., around 1800 EUR/ha. This transaction took place in 2019, in the municipality of Burdy (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

An agricultural property purchased at the lowest transaction price per 1 ha by the Olsztyn Branch Office of KOWR through the submission of a declaration of intent pursuant to the ukur Act.

Another interesting transaction, also performed in 2019, involved a total land area of 700 ha. The plots are located in two adjacent municipalities: Węgorzewo and Giżycko (Figure 10), and the average price per 1 ha was around PLN 25,000, that is EUR 5600. These land parcels are characterized by attractive location but are dominated by a typically agricultural function.

Figure 10.

The largest complex of agricultural land was purchased by the Olsztyn Branch Office of KOWR through the submission of a declaration of intent, pursuant to the provisions of the ukur Act.

The Act on the Shaping of the Agricultural System (the ukur Act) provides the legal ground for purchasing agricultural properties for the State Treasury Agricultural Property Reserve. This translates into a more extensive scope of the state’s impact on domestic agricultural policy. The provisions of the ukur Act make it possible to use farmland acquired in the private market to support positive structural changes in agriculture, in addition to which they introduce support mechanisms for family farms. Recently (since 2018), KOWR has been using the right of pre-emptive and right to purchase more intensively in order to buy agricultural property for the State Treasury Agricultural Property Reserve. The Olsztyn-based Branch Office, which covers the territory of the province of Warmia and Mazury, seems particularly active in this regard. The region is characterized by a large percentage of family farms and large-scale farms (e.g., agricultural enterprises with an area of 300 ha). The activities carried out by KOWR create opportunities for the further development and support of family farms. As underlined by Sikorska et al. [26], in the early years after Poland’s accession to the European Union, the goal was to strengthen the position of economically strong family farms on the agricultural market and to increase their area. Improvement of the area structure, particularly creating the conditions for enlargement of existing family farms, is promoted by the provisions contained in the ukur Act and by holding limited tenders by KOWR. Limited tenders are organized primarily for individual farmers who intend to enlarge their family farms. Since this entitlement was granted (mid-June 1999), limited tenders have been settled for farmers with the intent to increase the area of family farms for the purchase of 233.6 thousand hectares and the lease of 439.0 thousand hectares in total.

The reason is that while much farmland in this region has been incorporated into the STR and has already been distributed (sold), quite a considerable amount of agricultural land remains in the STR or has been distributed on a temporary basis (leased).

KOWR also takes measures aimed to develop non-agricultural activities which adhere to the concept of sustainable, multi-functional development of rural areas. Development is an unavoidable process; in fact, it is desirable, but it often occurs at the expense of rural areas, that is farmland and woodlands. An incentive for the appearance of new functions in rural surroundings is typically the development of infrastructure (especially, the construction of new roads or modernization of old ones) and urban pressure. First, land with low production potential is allocated for this purpose. This research paper presents examples of transactions that had a high potential for investment (e.g., the properties located in the municipality Mikołajki, Figure 8). The priority goal of the Polish state, however, is to build a land bank in the stock held in the State Treasury Reserve. These land resources will be returned to the State Treasury Reserve and will be distributed among private farmers under long-term lease agreements to increase the size of existing farms.

4. Discussion

Błąd [33] underlined the fact that the agricultural system determines directions in the socio-economic reforms, and its change constitutes a reform in itself. According to Bujak [34], socio-economic powers exert much more pressure on economic powers during the process of changing the agricultural system than vice versa. The reason is that the former can produce an effect much more rapidly because they deploy legal regulations. Nevertheless, the cited author is correct when concluding that although economic powers act more slowly, the consequences of their impact are more permanent and far-reaching.

After the collapse of the communist and socialist regimes in the Central and Eastern European countries (CEECs), the new governments quickly took steps to transform centrally planned market economies into market economy systems. One of the first measures taken, at the beginning of the 1990s, was the privatization of enterprises, land, and buildings. The legislation permitted individuals to own private property and allowed for land and buildings to become private property. The approaches to privatization and the methods are chosen by governments for achieving it varied according to the existing conditions and historical background of each country [35].

Despite the remarkable progress and success of land reform, one of its side effects, land fragmentation, has become a crucial issue, with detrimental implications for private and public investments, sustainable economic growth, social development, and natural resources [27,36].

Interventions in other countries include restrictions that relate to foreign ownership of land; ownership approval processes; upper and lower area limits; owner characteristics and land use requirements; pre-emptive rights to buy land; and measures to reduce land fragmentation. A range of motivations underpins the implementation of interventions to achieve policy objectives related to land ownership in various countries. Analysis of the motivations and the interventions allowed countries to be grouped according to the following typology, which identifies ‘foreign interest limiters’, ‘land use stipulators’, and ‘land consolidators’ [37].

After the dissolution of the State Agricultural Farms (PGRs), in the early years of operation of government agencies (currently, the KOWR) the Polish state was not interested in pre-emptive as the priority was the sale of agricultural land and its permanent distribution [8,12,26]. Since 2017, the sale of farmland has been restricted for the following five years. At present, this restriction has been extended for another five years. The main aim of the KOWR is to manage the real estate in the State Treasury Reserve. Hence, the main form of its distribution is now through lease contracts. The consequence of the restrictions imposed on the sale of farmland contained in the State Treasury Reserve was a rising interest in the right of pre-emptive and priority in the purchase of agricultural real properties by a state institution (the KOWR).

As confirmed by Degańska [38], the right of pre-emptive and the right of priority in the purchase of agricultural immovable properties impose certain limits on the free trade in the property as for the choice of a buyer. On the other hand, these measures are expected to prevent speculative trade of agricultural land [36], and above all, exclude persons not engaged in farming as potential buyers.

An operating family farm is "an independent production entity in which the basic production means belong to the farm’s owner (head of the family), who acts as the farm’s manager; the work is mainly performed by the farm’s owner and family members; the ownership and management of a farm are passed from generation to generation; the household is not separated from the farm; and the outcome of running the farm is a profit.” In this approach, the ownership, succession of generations, and benefits from the work performed as a whole family determine the family’s common interests. When analyzing one by one the distinguished characteristics of family farms, the attitude to the ownership of production assets, in particular the farmland, comes to the fore [26] (p. 34).

Own research [8,10,30] suggests that farmers prefer to work on the land that they own. This form of land ownership ensures the greatest freedom in planning and running agricultural production. Terms of lease agreements may not guarantee continuous land management (as for agreements performed with the National Support Center for Agriculture (KOWR) concerning the lease of land from the State Treasury Agricultural Property Reserve, the lessees pointed to statutory land exclusions, short tenancy duration, difficulties in making investments, etc.) [37].

Relatively less attention is paid to other important tasks performed by state agencies. Legal instruments here include the right of pre-emptive and the right of priority in the acquisition of agricultural real estate, which may considerably influence the trade in real estate, particularly in the shaping of the preferred ownership structure [38].

The activity of the KOWR aiming to build a bank of agricultural land is expected to support the running of family farms so that they will be competitive on both the domestic and EU markets. Svrznijak et al. [39] emphasized that in Croatia and in other countries of Central and Eastern Europe, only some of the state-owned farmland has been distributed for agricultural purposes. In Croatia, the state policy has been targeted at the sale of state agricultural land, an aim seen as a significant contributor to the consolidation of farms and increasing their average size. For example, in Scotland, there are no limits on the amount of land an individual can possess, and there is a model of large-scale, privately owned agricultural properties [36]. In Poland, prices of agricultural land have risen in recent years. There are many studies dealing with the impact of changes in the law on the trade in agricultural real estate properties [8,30,40], and attempts to influence transaction prices obtained both on the private market and for agricultural land purchased from the State Treasury Reserve [10,12]. Buying farmland is often an excessive burden for family farms. Currently (with the current grain prices), lease rents are also a heavy burden on family farms.

A comparison of the situation on the Polish agricultural land market to the trade in agricultural land in some other European countries brings to light many similarities. In principle, in all the so-called new EU member states, changes in the law pertaining to the trade in the land are pending [41].

The legal solutions implemented in Poland in 2016 were more restrictive than the German or French ones. The Polish law in this regard is more similar to Hungarian regulations. In Hungary, there is a limit imposed on an agricultural land parcel (1 ha) that can be sold without any additional regulations and permits, whereas in Poland this limit was initially 0.3 ha and now it is 2 ha. These regulations concern the sale of real estate from the Agricultural Property Stock of the State Treasury [29,42].

Glass et al. [36] in their study demonstrated that in the twenty-two countries across the world they analyzed (including 18 EU/EEA ones), the imposition of restrictions on land ownerships was motivated by speculative transactions rather than the intention to control the concentration of land that one person or one business entity may have. In countries where upper limits of the agricultural land area were introduced, the main aim of such legal regulations was to limit the purchase of land by foreigners, and these laws serve as mechanisms to control the planning of how farms operated [43,44]. In turn, Nikolić [45] underlines that the pre-emptive right in Serbia applies mainly to the purchase of agricultural land, whereas for example in France this instrument is used mostly for the purpose of planning the development policies of towns. This fact is also highlighted by Leger-Bosch et al. [46] in their study based on analyses of changes in the use of agricultural land in the context of social innovations in France.

The era of transforming from a centrally planned economy to a market economy in most Central and Eastern European countries began with profound reforms. In most countries of the former Soviet Union block, the first reforms were focused on land, the territorial base for various economic activities. In the Soviet times, the status of land ownership differed in the different countries in this part of the European continent: in some, land was nationalized and there was no privately owned land, while in others privately owned land prevailed. Moreover, the structure of land use varied from country to country: in some, large cooperative and state farms dominated, while in others small family farms continued to operate. Each country, depending on the situation regarding land ownership and use, chose its own way to implement land reform, while all of them held this task as a high priority on the political and economic reform agenda. Former large collective, state-owned farms were reorganized and privatized, often by returning the land to former owners or their heirs [41].

Regarding the ongoing agricultural reforms in the European region, in just ten years it turned out that the outcome of these transformations was not satisfactory. The new agricultural land plots created in rural areas were too small and fragmented for efficient agricultural activity and were not adjusted to the existing rural infrastructure. Fragmentation affected not only the ownership of land but also the way agricultural land was used.

Although nearly thirty years have passed since the onset of this process, in most of these countries the agricultural reforms have not been completed yet. The process of agricultural reforms could have been much more successful and less expensive if the goals and tasks had been clearly defined from the very beginning by the governments responsible for these reforms [41]. It is also worth mentioning that such goals and assumptions as well as the main principle should not be changed during the implementation of the reforms. The agricultural reforms, if successfully implemented, should not burden other reforms, but rather support the country’s economic development.

5. Conclusions

In the agricultural system, the basic production unit in agriculture is an agricultural farm. However, in light of the system’s underlying assumption, a particular type of farm has been distinguished, namely a family farm. The family farm emerges when a close bond is formed between an agricultural farm and a household.

One of the most important functions of a state understood as authority bodies, is to create the legal framework within which economic entities operate and transactions are concluded. The state is also responsible for the supervision of adherence to legal regulations. The shape of the legal system determines how the market functions. If that system is ambiguous, and compliance with the law is not enforced, then the market does not function properly. The land market in Poland has considerably liberalized since 1989. The accession of Poland to the EU structures caused new challenges in the management of real estate owned by the State Treasury. Since 2016, new restrictions have been imposed on the trade in farmland in Poland, which seem to be among the most restrictive laws in the European Union.

Based on the research presented in this paper, it can be concluded that the direction in undertaken activities that consist of the state’s interventionism in regulating the agricultural property market is correct and expedient in the long term. Measures taken by state institutions (KOWR) certainly support the development of family farms in Poland. Owing to these measures, the agricultural land reserve is enlarged, and land is distributed directly to private farmers, mostly under lease agreements. This enables farmers to develop family farms without having to expend much money to purchase land. It can also contribute to equalizing the level of the development of agriculture in Poland, and to making it more competitive in the EU market. Acquisition of farmland under lease agreement can also encourage young farmers to set up new farms and to ‘rejuvenate’ the Polish countryside. All these steps are certainly of great importance for the shaping of the agricultural system in Poland. These measures prohibit the transfer of agricultural land to persons who are not directly engaged in agriculture. Secondly, they are an instrument applied to monitor changes in farmland use, especially in the case of such land that is highly useful for agricultural production [47,48], that is monitoring the undesirable functional changes in agricultural areas (Hypothesis 1 verified). Without any doubt, it can be concluded that the activities carried out by the state institutions in Poland play a significant role in the shaping of the agricultural system in this country. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is confirmed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.K., K.K. and R.M.-B.; methodology, K.K., H.K. and R.M.-B.; software, H.K.; validation, H.K. and K.K.; formal analysis, K.K. and H.K.; investigation, K.K.; resources, K.K.; data curation, R.M.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K., H.K. and R.M.-B.; writing—review and editing, K.K., R.M.-B. and H.K.; visualization, H.K. and K.K; supervision, K.K.; project administration, K.K.; funding acquisition, K.K. and H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Support Center for Agriculture (KOWR), Branch Olsztyn, grant number: Umowa EDU/06/2022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Act of 2 April 1997 Constitution of the Republic of Poland; (i.e. Official Journal of 1997, Item 78, as Amended). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19970780483/U/D19970483Lj.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Stębelski, M. Rodzina jako wartość konstytucyjna. [Family as a Constitutional Concept]. Przegląd Konst. 2021. Available online: https://journals.law.uj.edu.pl/przeglad_konstytucyjny/article/view/970 (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Janowska, N. Konstytucyjne uwarunkowania ustroju rolnego w Polsce. [Constitutional conditions of the agricultural system in Poland]. Przegląd Prawa Konst. 2019, 1, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encyklopedia, P.W.N. Available online: https://encyklopedia.pwn.pl/ (accessed on 23 July 2021).

- Wilkin, J. Reformy agrarne i kształtowanie ustroju rolnego w II i III RP. In Proceedings of the Speech at the seminar IRWiR PAN, Warsaw, Poland, 13 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkin, J. Ewolucja znaczenia ziemi rolniczej w rozwoju wiejskiej gospodarki. Ciągłość I Zmiana Sto Lat Rozw. Pol. Wsi 2018, 2, 805–841. Available online: https://www.irwirpan.waw.pl/dir_upload/site/files/Monografia/28_Wilkin.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Jurcewicz, W. Ewolucja regulacji prawnej dotyczącej gospodarowania gruntami rolnymi w latach 1944–1984. [Evolution of the legal regulations on the management of arable land in 1944–1984]. Wieś Rol. 1985, 1, 131–172. [Google Scholar]

- Marks-Bielska, R. Factors shaping the agricultural land market in Poland. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milczarek-Andrzejewska, D.; Wilkin, J.; Marks-Bielska, R.; Czarnecki, A.; Bartczak, A. Agricultural Land-use Conflicts: An Economic Perspective. Gospodarka Narodowa. Pol. J. Econ. 2020, 304, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks-Bielska, R. Conditions underlying agricultural land lease in Poland, in the context of the agency theory. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowska, K.; Kryszk, H. Legal and market-related conditions underlying management of state treasury agricultural real estate in Poland. Eng. Rural Dev. 2017, 16, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, C.; Nowak, M.; Źróbek, S. The concept of studying the impact of legal changes on the agricultural real estate market. Land Use Policy 2019, 86, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Act of 11 April 2003 on the Shaping of the Agricultural System, (i.e. Official Journal of 2022, Item 461). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20030640592/U/D20030592Lj.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Puślecki, D. Problems of Legal Definition of Family Farm in Poland. EU Agrar. Law 2016, 5, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Act of 23 April 1964 and Civil Code (i.e. Official Journal of 2022, Item 1360). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19640160093/U/D19640093Lj.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Act on Agricultural Tax, of 15 November 1984 (i.e. Official Journal of 2020, Item 333). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19840520268/U/D19840268Lj.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Darnhofer, I.; Lamine, C.; Strauss, A.; Navarrete, M. The resilience of family farms: Towards a relational approach. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 44, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeub, B.E.; Chappell, M.J.; Wittman, H.; Ledermann, S.; Kerr, R.B.; Gemmill-Herren, B. The state of family farms in the world. World Dev. 2016, 87, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi, L.A.; Gemmill-Herren, B.; D’Annolfo, R.; Graeub, B.E.; Cunningham, S.A.; Breeze, T.D. Farming approaches for greater biodiversity, livelihoods, and food security. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2017, 32, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer-Nawrocka, A.; Poczta, W. Nowe szanse i zagrożenia dla polskiego rolnictwa wynikające z polityki unijnej i sytuacji globalnej. In Polska Wieś 2022. Raport o Stanie Wsi; Wilkin, J., Hałasiewicz, A., Eds.; Wyd. Nauk. SCHOLAR: Warszawa, Poland, 2022; pp. 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Winczorek, P. Komentarz do Konstytucji Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z Dnia 2 Kwietnia 1997 r; Liber: Warszawa, Poland, 2000; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Rakoczy, B.; Bień-Kacała, A. Gospodarstwo rodzinne jako podstawa ustroju rolnego w świetle Konstytucji RP z 1997 roku. Przegląd Prawa Ochr. Środowiska 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brookfield, H. Family farms are still around: Time to invert the old agrarian question. Geogr. Compass 2008, 2, 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, E.; de la O Campos, A.P. Identifying the Family Farm. An Informal Discussion of the Concepts and Definitions; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2014; Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/288978 (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Pisani, D.J. From the Family Farm to Agribusiness: The Irrigation Crusade in California and the West; University of California Press: London, UK, 2021; pp. 1850–1931. [Google Scholar]

- Sikorska, A.; Karwat-Wozniak, B.; Chmielinski, P. Changes in the agricultural land market and agrarian structure of individual farms in Poland. Econ. Sociol. 2009, 2, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilewicz, A.; Bukraba-Rylska, I. Deagrarianization in the making: The decline of family farming in central Poland, its roots and social consequences. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 88, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J. Impulses towards a multifunctional transition in rural Australia: Gaps in the research agenda. J. Rural Stud. 2006, 22, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowska, K.; Kryszk, H.; Cymerman, R. Identyfikacja czynników wpływających na kształtowanie się cen transakcyjnych nieruchomości rolnych będących w zasobie ANR OT Olsztyn. Stud. Pr. Wydziału Nauk Ekon. Zarządzania 2014, 36, 303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, C.; Źróbek-Różańska, A.; Źróbek, S.; Kryszk, H. How does government legal intervention affect the process of transformation of state-owned agricultural land? The research methods and their practical application. Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 105769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrobocińska, K.; Napiórkowska-Baryła, A.; Świdyńska, N.; Witkowska-Dąbrowska, M. Środowisko a Konkurencyjność Gmin Na Przykładzie Województwa Warmińsko-Mazurskiego; Wyd. UWM w Olsztynie: Olsztyn, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Brodziński, Z.; Juchniewicz, M.; Łukiewska, K.; Marks-Bielska, R.; Nasalski, Z. Ustawa O Kształtowaniu Ustroju Rolnego a Kreowanie Rozwoju Rolnictwa I Obszarów Wiejskich; Wyd. UWM w Olsztynie: Olsztyn, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Błąd, M. Sto Lat Reform Agrarnych W Polsce; Wyd. Naukowe SCHOLAR: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bujak, F. O Naprawie Ustroju Rolnego W Polsce; Składy Główne w księgarniach Gebethnera i Wolffa: Warszawa-Lublin-Łódź, Poland, 1918. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J. Property rights, land fragmentation and the emerging structure of agriculture in Central and Eastern European countries. eJADE Electron. J. Agric. Dev. Econ. 2006, 3, 225–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, J.; Bryce, R.; Combe, M.; Hutchison, N.; Price, M.F.; Schulz, L.; Valero, D.E. Research on Interventions to Manage Land Markets and Limit the Concentration of Land Ownership Elsewhere in the World; Scottish Land Commission: Scotland, UK, 2018. Available online: https://landcommission.gov.scot/downloads/5dd6c67b34c9e_Land-ownership-restrictions-FINAL-March-2018.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Stacherzak, A.; Hełdak, M.; Hájek, L.; Przybyła, K. State interventionism in agricultural land turnover in Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadańska, K.A. Preemptive, back-in and redemption rights as well as the right of priority in acquisition of real estate. Real Estate Manag. Valuat. 2015, 23, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Svržnjak, K.; Franić, R. Developing agrarian structure through the disposal of state-owned agricultural land in Croatia. Agroecon. Croat. 2014, 4, 50–57. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/125556 (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Blaszke, M. Impact of legislative changes on agricultural property trading. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2020, 64, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasaev, G.; Khlystun, V.; Kurowska, K.; Prsova, V.; Vasilieva, D.; Vlasov, A. Land Reform: From State Monopoly to Property Diversity; Samara Federal Research Center of Russian Academy of Sciences: Samara, Russia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kurowska, K.; Ogryzek, M.; Kryszk, H. Kształtowanie się cen nieruchomości rolnych po wstąpieniu Polski do Unii Europejskiej na przykładzie Agencji Nieruchomości Rolnych OT Olsztyn (Development of agricultural real estate prices after Poland’s accession to the European Union on the example of the Olsztyn branch of APA). Stud. Obsz. Wiej. 2016, 42, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, A.; Adams, V.M. Planning for the future: Combining spatially-explicit public preferences with tenure policies to support land-use planning. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu-Mag, R.M.; Petrescu, D.C.; Reti, K.O. My land is my food: Exploring social function of large land deals using food security–land deals relation in five Eastern European countries. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, S. A Serbian perspective on preemptive rights: Change that was necessary. In Instruments of Land Policy; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 218–222. [Google Scholar]

- Léger-Bosch, C.; Houdart, M.; Loudiyi, S.; Le Bel, P.M. Changes in property-use relationships on French farmland: A social innovation perspective. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaian, P.; Guri, F.; Rajcaniova, M.; Drabik, D.; y Paloma, S.G. Land fragmentation and production diversification: A case study from rural Albania. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowska, K.; Kryszk, H.; Marks-Bielska, R.; Mika, M.; Leń, P. Conversion of agricultural and forest land to other purposes in the context of land protection: Evidence from Polish experience. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).