1. Introduction

The United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 26) [

1], which took place from 31 October to 12 November 2021 in Glasgow, made the world reflect again on the need to carry out concrete actions to stop global warming and to achieve the main objective of the Paris Agreement: “to keep the increase in the average temperature of the planet below 2 °C and work to limit this increase to 1.5 °C” [

2].

Exceeding these temperature levels would unleash devastating consequences for life on the planet: loss of flora and fauna, a rise in sea level, droughts, and melting of snow-capped mountains, among others. Acting now means avoiding reaching a point from which we could not return (2 °C) and which could extinguish humanity in the long term. All this, linked to the appearance of the COVID-19 virus, led 200 world leaders to reflect on a green recovery that implies the creation of sustainable jobs and better public health systems, as well as the prioritization of protecting the environment so as to protect future generations [

1].

It is important to emphasize that the president of the Republic of Ecuador, Guillermo Lasso, in his participation in the summit, promised to reduce 22.5% of emissions by 2025. He presented the idea of creating a national transition plan for the decarbonization of the economy, with investment projects in electric mobility, renewable energy, agriculture, tourism, habitat, and circular economy, as well as the establishment of a new marine reserve covering 60,000 square kilometers in the Galapagos Islands [

3].

Given the urgent need to make the population aware of the importance of taking action to preserve the planet, it is undeniable that the media play a fundamental role in disseminating content that reveals the impact of human activities on the environment, the risks that they represent for their subsistence, and the importance of taking measures to preserve the ecosystem.

Since we are immersed in a digital world and considering the massive reach of the media, it has become the ideal setting for public opinion, reception of proposals, exchange of experiences, and debate. The media have provided a space where ideas and thoughts are contrasted, which contributes to the generation of approaches that are incorporated into the strategic design of a sustainable model of environmental care.

The objective of this exploratory research is to analyze, in a small sample, the role of digital media in the development of messages for the care of the environment in Ecuador in the context of the United Nations Conference on Climate Change (COP 26) and to make proposals to develop environmental journalism in the country.

1.1. Literature Review

The preservation of the environment and the role of digital communication are two transversal axes that interact throughout this research. They are addressed individually and together to understand how this issue is being treated and to thoroughly review the importance of the environment in media agendas in order to establish guidelines from the perspective of environmental journalism as a fundamental task in the dimensions of communication.

The issue of caring for the environment in Ecuador has become a problem that has worsened over time, precisely because the population has not been made aware of this long-term catastrophic phenomenon, even though everyone has witnessed climate change and its consequences on endangered species and the degradation of endemic flora.

1.1.1. Environmental Journalism

It is important to remember that mass communication became interested in environmental problems in the 1970s and 1980s when environmental journalism was first heard of [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Environmental demands were echoed in the mass media during the ecological catastrophe of Chernobyl (1986). These voices tried to warn about the profound deterioration to which the capitalist and socialist production models have led. In addition, large environmental movements emerged, such as Greenpeace (1973), Friends of the Earth (1971), and the first green parties (such as Grünen in the Federal Republic of Germany); in the 1980s, they managed to attract enough attention in academia that research was undertaken, environmental education campaigns were generated, and speeches that promoted unsustainable consumption and production were analyzed [

7,

8].

The definition of environmental journalism has acquired various names depending on the professionals who have tried to define its functions. It is known as ecological, environmental, or green journalism [

9]. According to Fernández Reyes, environmental journalism is a specialized journalism, which is currently among the most visible contributors to the “construction” of the social representation of climate and global change in general [

6], making the media the main resource available so that most of the population can have access to information surrounding environmental problems.

This author states that environmental journalism can be considered specialized journalism because it meets the requirements regarding experience in the application of an investigative journalistic methodology, professional associations, and the fulfillment of an important social function and specific demand within society [

6]. Its evolution has basically taken two directions: (1) the one he calls “the informer” who comes to environmental issues “by chance, mandate or opportunism” and (2) “the environmentalist who writes”, who he places in the category of the militant who finds in journalism a way to support ecology [

10]. These two forms of environmental journalism can be appreciated in the debates of the International Federation of Environmental Journalists (IFEJ) and committed environmental journalism. Pérez de la Heras identifies that both conceptions converge in terms of the position of the professional and the specialized treatment, each with its own advantages and disadvantages.

The evolution of environmental journalism prompted Fernández Reyes to define it as the journalistic exercise or specialized journalism that deals with the information generated by the interaction of humans or living beings with their environment, or the environment itself, actively participating in the achievement of sustainability [

6]. Cerrillo refers to this as a transversal discipline [

11], resulting in pedagogical functions related to the promotion of values, attitudes, and responsible behaviors, as well as the assignment of roles involving: “media supervision and monitoring of public policies and private actions; the implementation of agendas and approaches committed to environmental justice, as well as news coverage of responsible and respectful actions concerning the environment” [

7].

In Latin America, activism prevails, in which the fundamental mission of environmental journalism is to encourage society and the holders of the constituted powers to undertake those necessary “actions to save the Planet and humanity” [

12].

1.1.2. Another Look to Address the Construction of Messages

Although the rights of nature are enshrined in the Constitution of Ecuador [

13], they are violated in the search for maximum financial wealth at the expense of natural resources [

14]. The productive structure responds to a hegemonic ideology based on the capitalist world-system, which, among other social and political effects, generates excessive consumption of plastic and fossil fuels and encourages construction, ultimately causing the effect of global warming [

15].

Although various awareness-raising exercises have been carried out among the population, such as campaigns in favor of the environment, they do not seem to have any effect if we consider the behavior of individuals in their daily lives [

16]. Thus, it is considered that the development of the various communication products from the media has had an erroneous approach. The first step should be to understand how “consumerism”, which is one of the foundations of the capitalist model in which we have lived for centuries, has taken root as part of the culture. In other words, it has modeled a collective imaginary, where there is a direct relationship between consumption and the development or success of an individual [

15].

In the same way, this ends up being expressed in the way individuals communicate and interact with the world. Thus, consuming implies an event full of meanings, whose analysis can make realities and identities visible. “We communicate through the objects that we acquire based on the ideas they project… to talk about this culture is to ask about the role played by capitalist exchange, objects, and their dynamics in the modern world” [

17].

Thus, the generation of behavioral changes in society implies a deconstruction of the culture that surrounds them and the generation of new collective imaginaries, establishing the value of individuals away from what they come to possess. This change would imply the generation of less waste, the possible disappearance of fast fashion, and more regulations for companies regarding planned obsolescence, among others [

15]. This is where the media take a leading role in the dissemination of this problem. Although it is worth keeping in mind that “the management of the media has become one more commercial activity, without taking into account the important social function to which they must respond” [

18].

After achieving this deconstruction, multimedia products that promote care as a social responsibility and not as an individual choice should be generated. This ethic of care, proposed by Aliaga, is configured as a public value for the construction of citizenship [

15]. In this way, congruence with the consequences of our actions would be generated, and the need to forge acts of reduction, reuse, and recycling of waste would be internalized. The volume of our garbage would also be significantly reduced, and we would save energy. This should be the horizon of the media and government authorities. “The issues analyzed must be part of the political and public, and not just be reduced to the individual style of people, as simple consumers a little more informed” [

15].

1.1.3. Media That Generate Impact

Ecuador has very rich biodiversity, with distinctive fauna, characteristic multiculturalism, and attractive natural spaces not only for tourism, but also for communities, peoples, and nationalities who consider the natural environment as the most sacred and valuable thing [

19]. The territory has the obligation and commitment to defend its natural wealth, not only for the good of the economy but also for the well-being of citizens.

If the damage caused to nature leads to its compromise, the participation of citizens and the intersection of quality journalism with an environmental focus become complementary elements that converge in the face of the emergency demanding alternatives for a sustainable solution be found in the medium and long term in order to try to stop the environmental decline [

20,

21]. Thus, it is logical to think that the media constitute an essential factor in achieving communication of an awareness about care and management of the environment, since they are supposed to inform about what is being done, what has been discovered, environmental problems, and other issues related to the environment [

22].

The alienated thinking of people is produced by what they see through images on television or the internet, which points exactly to the abuse of nature in exchange for having certain luxuries. The misrepresentation of reality through the media is a conflict that expresses serious issues towards care for the environment. Hence, the importance of generating new knowledge and reflection on the appropriate measures that should be taken as quickly as possible to try to stop the natural disasters is clear to see [

15].

1.1.4. Environmental Educommunication

Education is a fundamental ally for the internalization of messages in people’s daily lives. In Latin America, it is possible to observe how the alliance of this discipline with communication has generated great contributions to the development of societies. Educommunication (among whose main exponents is Mario Kaplún [

23,

24]) is linked to the environment by digital media and can be essential to achieving the common goal of safeguarding life on our planet through changes and modifications in the daily actions of individuals towards nature [

25].

According to Novo [

26], development must be rethought by considering who it is for, the reason behind it, and how it will occur. The author states that, through educational processes, it is possible to contribute to the deconstruction of the old imaginary of domination in a world of continuous growth and unequal distribution. Education also has the challenge and the possibility of promoting new values and imagining alternative scenarios [

27]. Educating environmentally is an opportunity to contribute to the emergence of the new paradigm. Environmental education can and should be, without a doubt, one of the axes of the transition from one millennium to another [

28].

Education is combined with communication to generate these concrete actions. As Cueto points out [

25], some of the critical points of social transformation that environmental education raises and that are related to environmental education or communication can summarized by the following:

- -

There is a lack of dissemination and educational effort regarding urban environmental realities.

- -

There are many educational/environmental works with purely ecological aspects (nature), which leaves the cultural and social aspects that are part of the environmental problem aside, thus hindering the development of the conception of a systemic vision of the environment in public opinion.

- -

Very few results have obtained the actions that universities have undertaken to incorporate the environmental dimension and transform it from thematic transversality to a practical part of teacher training processes. This affects developments that require environmental education as part of their integral formation.

- -

There are problems in the social appropriation of knowledge and the information derived from environmental research studies. This is due to the scarce diffusion made by the institutions or organizations responsible for their production, which is evidenced by the absence of a pedagogical–didactic language that facilitates the access of individuals and groups to information; qualifying the processes of understanding the environmental reality is indispensable [

25].

1.1.5. Towards a New Model of Journalism

Communication must fulfill its role of being a safe space for the exchange of ideas, opinions, proposals, and experiences in such a way that it can transform the actions of individuals in the preservation of the natural environment and create sufficiently attractive, reflective, and critical communication products [

29]. On the other hand, the media, in the process of adapting to the new digital platforms, have found renewed ways of managing information, making it more dynamic and specific in terms of its target audience. Being part of the world of networks provides access to more detailed and complete information on a particular topic [

7].

Talking about communication that fulfills the role of promoting analysis, knowledge, criticism, and reflection on the current situation that the world is going through implies talking about the deterioration of nature caused by human beings. It is important that communication professionals specialize in the subject, and that they become experts in these areas so that they can transmit their knowledge to other people so as to promote awareness [

7].

It is necessary to highlight the advantages of digital forms of media regarding their freedom from commercial interests and their potential as fertile ground for the implementation and development of environmental journalism. According to Fernández Reyes [

6], the dialogue between the investigations carried out and the media must be strengthened since they fulfill the function of reinterpreting and adapting the results achieved so that average citizens can understand them. This allows for interaction with these findings and understanding of the results in people’s everyday lives.

Due to this, it is said that “the ecological, on the other hand, is more conflictive because it’s associated with ideology, commitment, indoctrination, dogma, militancy, and struggle. Undoubtedly, it’s a term full of intentionality and even revolutionary resonances for many” [

29]. From all this, “sustainable journalism” is derived, which manages environmental, economic, or social information that may affect the resources available to future generations [

9].

2. Methods

This research is focused on studying the trends [

30] present in the environmental discourse of two digital media, the websites of “

El Comercio” and “

Radio La Calle”, both of which are based in the city of Quito, the capital of Ecuador. The central idea of the study is to contrast the coverage of ecological issues in two representative Ecuadorian media outlets with quite different editorial positions.

In the case of the digital platform of “El Comercio”, it comes from (or is part of) a historically conservative Ecuadorian newspaper founded in 1906. Currently, its Facebook page has more than 3.5 million followers and represents one of the traditional media outlets with a large number of digital followers in the country. This newspaper has an editorial line very close to the political positions of current president Guillermo Lasso, a right-wing politician.

Meanwhile, “Radio La Calle” is an exclusively digital media outlet that was created in 2010 and practices militant journalism from the left. Its contents are highly critical of the government of President Lasso. This new medium defines itself in social media as “an original, courageous, direct and frontal communication medium” and has just over 160 thousand followers on Facebook.

For this, a comparison was made of the contents generated regarding care of the environment during the United Nations Conference on Climate Change (COP 26) (held between 31 October and 12 November 2021 in the city of Glasgow) through use of textual and discursive analysis “which accounts for both the surface level of a text and its deep level” [

31]. This is to understand the emphasis given to this event within its agenda. We reviewed the Facebook posts and search engine results for both media outlets for the 13 days of the summit.

An attempt was made to understand the configuration of the communicational products produced by the two mentioned media outlets based on the analysis of frequent and distinctive words, central themes, ideological position, and characteristic language such as density and readability. In the first place, to identify these text elements, Voyant Tool [

32] software was used, which detects keywords, themes, and phrases from which deeper analyses can begin.

On the other hand, additional data were collected through semi-structured interviews with some activists and experts in communications who defend the environment by generating content related to it. The interviews consisted of a meeting to exchange information between one person (the interviewer) and another (the interviewee) or others (interviewees) [

31]. In the case of semi-structured interviews, they are within the qualitative research approach because they benefit from the depth of ideas, amplitude, interpretative richness, and contextualization of the phenomenon [

31]. In this sense, semi-structured interviews are based on predefined questions and the interviewer is then free to introduce additional questions to specify concepts or obtain more information on the desired topics. The interviews seek to contextualize and verify some findings in this exploratory research through an information triangulation exercise [

33,

34]. Throughout their careers, the interviewees have provided complementary perspectives on environments, impacts (involving the environment, health, social factors, economic factors, and citizen participation), media (ideological approaches, responsibility, content generation), educommunication, academia in Ecuador, and governments (public policies and financing), thus expanding the convergence of the media in the digital world and, of course, the development of content that has an impact on the environment.

Interviews were conducted in person and through the Zoom platform, lasting between 20 and 30 min. The communication office of the Ministry of the Environment, Water, and Ecological Transition of Ecuador preferred to answer the questions in writing. Six people were selected, considering their relationship with the protection of the environment and content management, to answer questions about the role of the media in the generation of content that promotes environmental care. The experts interviewed were:

- -

Diego Ortiz (DO), journalist with 13 years of experience and the current editor of the environmental section of the newspaper El Comercio. He has a specialization in “Climate change, cities, and urban leadership”.

- -

The Ministry of the Environment, Water, and Ecological Transition of Ecuador (ME), who chose to answer questions in writing (with answers signed by the communication office).

- -

Andrea Durán (AD), Business and International Relations graduate, founder of Oceanids (an academic network of women created in 2020 to promote environmental education, mainly focused on the seas), and generator of environmental journalism.

- -

Cristina Naranjo (CN), Educommunication Management masters graduate. She has worked mainly in interventions related to communication for development. She has participated in various projects, such as 2KR, which focused on farmers in small towns, and an audio-visual biotic monitoring project for block 31 in Yasuní, among others.

- -

Micaela Puetate (MC), active member of the “Simbiosis de Ambato” group (which manages environmental awareness projects in Tena), leader of the “Guardians for a Green Future” project, and manager of the “Muyo” project (which covers issues related to gender, the environment, and the LGBTQ+ community).

- -

Liz Tanguila (LT), an Environmental Engineering student at Universidad Estatal Amazónica. Member of the FOIN (indigenous organizations of Napo province), which fights against illegal mining. This organization is also part of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon (COFENAIE).

3. Results

The Ministry of the Environment, Water, and Ecological Transition of Ecuador seeks to guarantee the quality, conservation, and sustainability of the country’s natural resources. This public body considers the declaration of a new marine reserve covering 60,000 square kilometers in the Galapagos Islands as a milestone for the country, which adds to the existing conservation area on the islands (going from 138,000 to 198,000 square kilometers). Likewise, in communication with its communication office, the ministry highlights that in the framework of Ecuador’s participation in COP 26, the president of the republic, Guillermo Lasso, announced a targeted reduction in methane emissions of at least 30% by 2030.

3.1. Brief Content Analysis

As a result of the review of the publications of two digital media outlets, “

El Comercio” and “

Radio La Calle”, the following pieces were identified during the United Nations Conference on Climate Change 2021 (COP 26) held from 31 October to 12 November, as shown in

Table 1.

A total of eight communication pieces on the “El Comercio” website related to COP 26 and Ecuadorian issues, six of which were news articles and two of which were editorials. In contrast, “Radio La Calle” only published two pieces about COP 26. It should be noted that “El Comercio” shares around twenty posts per day on different issues, while “Radio La Calle”, on the days studied, shared between four and eight posts per day. In other words, “El Comercio” publishes three to four times more content than “Radio La Calle”. Both media outlets have other publications about COP 26, but they were not considered because they were either outside the defined period or did not refer to Ecuador.

The set of articles published by “

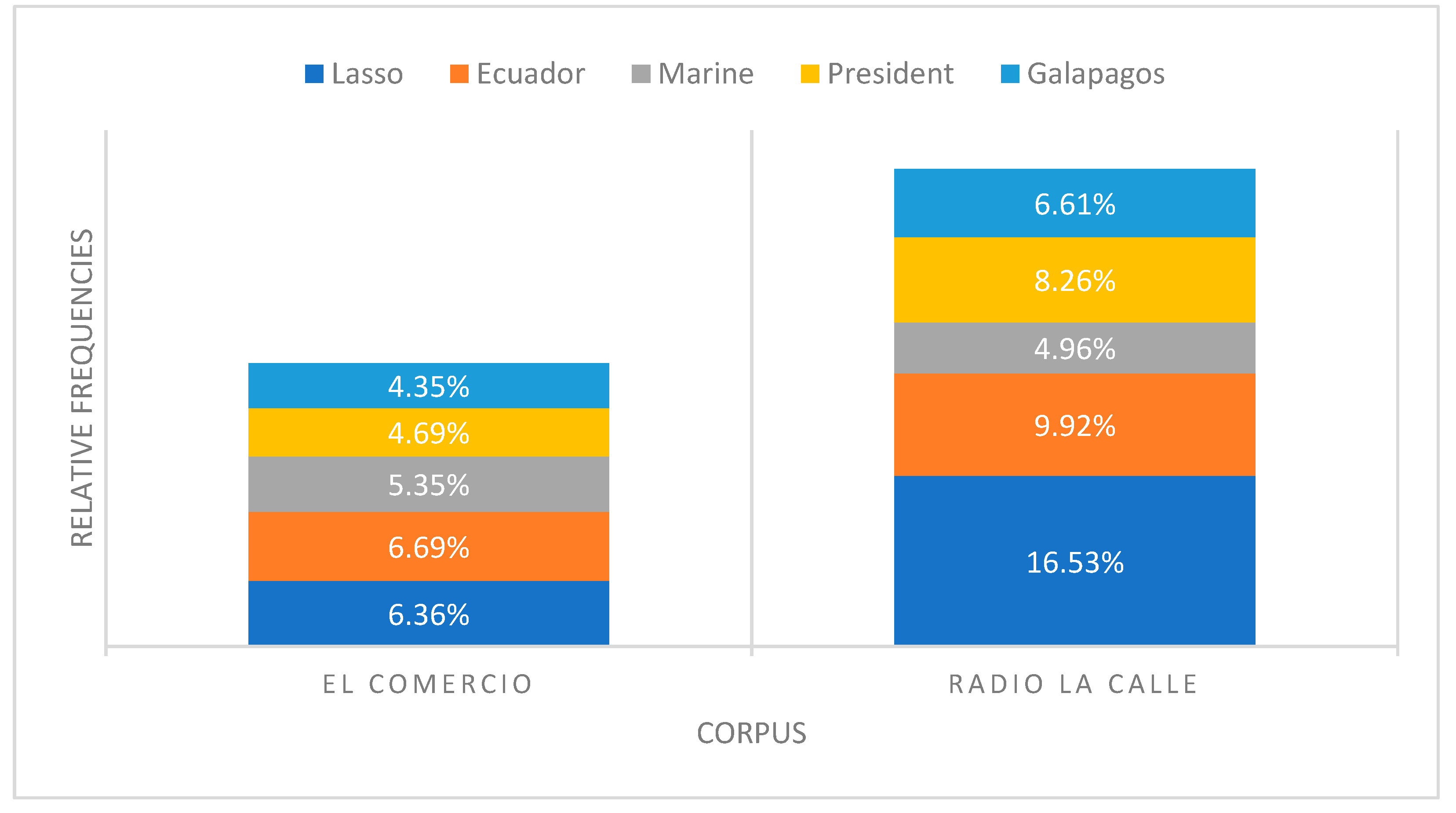

El Comercio” on COP 26 has a word count of about 3000 words, which is approximately 370 words per piece. In this corpus, two terms stood out: Ecuador and Lasso (the name of the country and the president’s surname) [

35]. This means that news coverage of the country’s role in COP 26 focused on the presidential announcement. The third issue highlighted by

El Comercio was the expansion of the marine reserve in Galapagos, the central theme in all the news analyzed in this newspaper [

35].

Meanwhile, the two news items about COP 26 from “

Radio La Calle” totaled 605 words, with an average of 302.5 words per piece [

36], a total length slightly less than “

El Comercio”. In this pair of news articles, Lasso is the most frequent word, followed by Ecuador. Both words are the same as “

El Comercio”, although in reverse order. The third term with the most mentions was Galapagos, the name of the islands where the marine reserve was expanded [

36]. At this point there is also similarity with “

El Comercio” because although the keyword in the other medium was marine, it referred to the same topic. See

Figure 1.

The fact that the president of Ecuador, Guillermo Lasso, participated in COP 26 and announced the expansion of the marine reserve in Galapagos was the central news in the two media outlets. However, how can we establish differences in the treatment of information from the two analyzed media outlets?

Table 2 shows distinctive words in the corpus of both publications. Distinctive words refer to particular and different words used by each medium, allowing for initial comparison of the treatment of information.

The distinctive words associated with “

El Comercio” are related to the participation of countries in the international summit that promotes environmental conservation in the face of climate change. In this sense, the terms “countries” and “conservation” complement the meaning of the most frequent words. Therefore, it follows that the treatment of information is either neutral or tends to favor the work of the president of Ecuador. However, in the case of “

Radio La Calle”, the “distinctive words” introduce a different emphasis. The terms “b3w” and “investments” appear. First, “b3w” refers to the “Build Back Better World” initiative led by the United States of America’s President Joe Biden. In addition, “investments” refers to environmental market solutions. In “

Radio La Calle”, there is an intention to highlight the closeness of Ecuadorian foreign policy to the United States and environmental issues to market solutions. Now, considering that this second medium has a close to leftist political position when highlighting the aspects, it does so with a critical intention. This questioning position is also evident in the headlines in

Table 1.

3.2. Missing Topics

The Ministry of the Environment, Water, and Ecological Transition considers that the second most important topic regarding Ecuador’s participation in COP 26 was the commitment to reduce the country’s emissions by 30% by the year 2030. However, the textual analysis does not show the importance of that topic.

Some of the interviewed activists explained that other issues related to environmental impact were not considered. There were no communication products related to the Yasuní-ITT Initiative, one of the sectors most affected by oil extraction. Neither was the precariousness of the communities discussed, which continues to open a gap in knowledge and awareness among Ecuadorian citizens. Galapagos is not the only area at risk in Ecuador, many localities are at risk of completely disappearing.

Unfortunately, no more of a significant effort was made to attract and raise awareness of issues directly addressed at the international summit by “Radio la Calle”. Even though the outlet considers itself as a platform that provides information with a different approach, it is still a relatively young outlet in which there are areas to polish.

Some parts of

El Comercio’s coverage of COP 26 were superficial, so attention was focused on images of President Guillermo Lasso and his interactions with the leaders of the “first world” (

Table 1). The emphasis in two of the articles was placed on the manifestation of the famous American actor Leonardo DiCaprio, billionaire Jeff Bezos, and Lasso’s statements, but there was no great coverage and inclusion of actors outside the primary elite.

3.3. Textual Complexity

All the interviewees agreed that all communication media have the responsibility to generate content that promotes environmental care. This content must be clear, with adequate language that allows everyone to easily understand what is happening in the world and the repercussions in their lives. “We as content generators have the responsibility to deliver a clear, precise, and concrete message (…) We have a responsibility to send a clear message” (MP).

Although some news articles from “

El Comercio” and “

Radio La Calle” provide interesting counterpoints, both outlets have somewhat complex writing. The complexity of the writing is evident in the average of 27.4 words per sentence in “

El Comercio”, while “

Radio La Calle” reaches an average of 28.8 words. Simple journalistic texts usually have less than 20 words per sentence; however, the sentences of the analyzed pieces have a high average [

36].

Some journalists and academics consider that, to address these issues journalistically, there is a need for constant specialization. Therefore, journalists must be trained to translate this scientific language into one closer to the people. Additionally, due to the fluctuation of the data, this specialization must be almost annual.

Although alternative journalism has been approached by small digital media outlets, regarding environmental issues, it is almost impossible to do it on your own because it implies a whole process of searching for scraps until complex investigations are completed. Some of this occurs with “

Radio La Calle” (see

Table 3), which despite having a smaller news output on average than “

El Comercio” not only has longer sentences but also has a higher density of vocabulary.

4. Discussion

Throughout the investigation, coverage inefficiencies were determined by both digital media outlets because their role in caring for the environment is scarce and shallow. Except for two pieces out of ten, the treatment of information is not very deep. Both the conservative corporate media and the alternative left media lack an attempt to reorganize the agendas (the issue of preservation does not fit in their media agendas) and the space they provide for environmental issues is narrow.

As the interviewed specialists point out, if enough information, criticism, and reflection are not generated, then it is impossible to produce public opinion. Consequently, an attitude that ignores the natural catastrophes that happen around us is unleashed and naturalized. The problems with the environment remain because there is no social pressure. After all, the media are not fulfilling their role of being a free space for debate or a space for the exchange of ideas and experiences. The deconstruction of ambiguous concepts is still an extensive task that Ecuador, as a multicultural country, needs to go through.

In this sense, this research invites us to reflect on the need to understand what the role of digital communication has been in the development of communication products regarding care of the environment in Ecuador. A brief observation of media with a different editorial approach finds that a merely informative space predominates, while reflection and criticism are scarce. If we talk about an environmental transformation, the participation of informed citizens is crucial. It is also important to emphasize that the content broadcast in digital media, whether private or alternative, must share the same objective of promoting the participation of people so that they contribute to the urgent task of caring for the environment. It is imperative for journalism to consider the construction of a special guide that leads it to complement the most urgent demands of the Ecuadorian people, especially those of people who live in the middle of nature. In this way, the rest of the urban population is offered an approach to realizing its emerging reality.

To achieve the media’s objective of influencing the forms of consumption and interaction Ecuadorians have with the environment, it is necessary to change how journalism is conceived. In other words, building environmental journalism is required. It is necessary to grant independent spaces for analysis, to specialize personnel in topics related to this, and to implement public policies that finance professional training processes, research, and dissemination of content aimed at raising citizens’ awareness of environmental issues. It is also necessary to promote concrete actions to give voice and visibility to people who, on their own initiative, have achieved a national and international position in defense of the environment.

Environmental journalism is a reality in other countries; however, when asking the interviewees about the possibilities of formal training regarding environmental issues, they agreed that there is a total absence of specialization in these issues with sufficient academic rigor. Therefore, they have been self-taught, and the construction of their content arises from research processes and dialogue with other activists linked to environmental care.

“There are great journalism careers in the country, but not specialized ones. So, if you want to do certain types of things, you must be self-taught, and that is something that the academic preparation of Ecuador lacks” (AD). We are talking about Ecuador, a mega-diverse country which has been the site of multiple investigations related to the environment. This gives our professionals expertise that is valued internationally, and they end up leaving the country due to better job offers. This prevents the initiation of long-term training processes which would allow us to understand these very diverse conditions and start building products from the particularities. It was also agreed that what we consider to be “Environmental Education” must be reformed as it is currently based on simplistic solutions such as recycling which do not generate changes. It is necessary to adopt the main premise of ecology (“we are all part of a whole”) to build actions that transcend beyond individualism and generate profound changes.

However, despite understanding the environment also implies the development of studies based on each sector and its situations, more progress needs to be made to generate a true reactivation of the environment. These good environmental practices must focus on personal context by considering the places of interaction, the actions of citizens, their professions, or the roles they play within their communities so concrete proposals can then be generated.

This explains why the campaigns launched internationally and replicated in our territory do not generate mobilization in Ecuadorians—they do not identify with the problem nor with the people and situations presented on the screen. This shows that caring for the environment is not something that transcends them and evidences the absence of on-site research, especially in traditional media.

5. Conclusions

In theory, there is a notable difference in the focus, depth, and importance given by alternative and traditional media to environmental issues within their agendas. The construction of their content comes from intentions and objectives regarding their different audiences. While the former seeks allies to fight and defend their territories, the latter seeks to have one more story to tell.

In Ecuador, alternative media and activists are interested in generating and creating content to raise public awareness about environmental care. However, there are financing, dissemination, and target audience obstacles which do not allow full visibility of their work.

Content production with efficient diagnoses requires in-depth research based on an understanding of the complexities of each sector within Ecuador. It is not possible to replicate campaigns or act based on imaginaries because concrete results are not obtained, and resources and time are then wasted.

Environmental journalism has been developed in Ecuador in a self-taught way and it is known by other names; however, it requires academic formalization, the establishment of clear guidelines, the generation of public policies, and proper financing.

This study invites us to broaden our perspective and delve into more specific issues in order to improve journalism. It also allows for investigation into the treatment of “Environment” within academia, curricular aims, the dissemination of research carried out on this subject, and the role of the government in the management of public policy for the development of specialized journalism. Likewise, the construction of micro spaces for the interaction of individuals promotes conscious environmental practices, which communicate the construction of imaginaries away from consumerism and individualism.

To promote the rational use of natural resources and the conservation of ecosystems in Ecuador, it is essential that the media, taking advantage of their influential position, encourage interest in information through communication products; this should be supported by professionals specialized in ecological and sustainability issues who then guide the construction of content on environmental issues.

Although this small study addressed the work of two media outlets and consulted a small number of experts in Ecuador, this type of research, focused on the practices of environmental journalism, should continue to be expanded to more broadly analyze the role of the media in different relevant moments with the idea of delving more deeply into the differences, similarities, achievements, and deficiencies between the different types of media and the recommendations of specialists to improve their performance.