Impacts of COVID-19 on Sustainable Agriculture Value Chain Development in Thailand and ASEAN

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

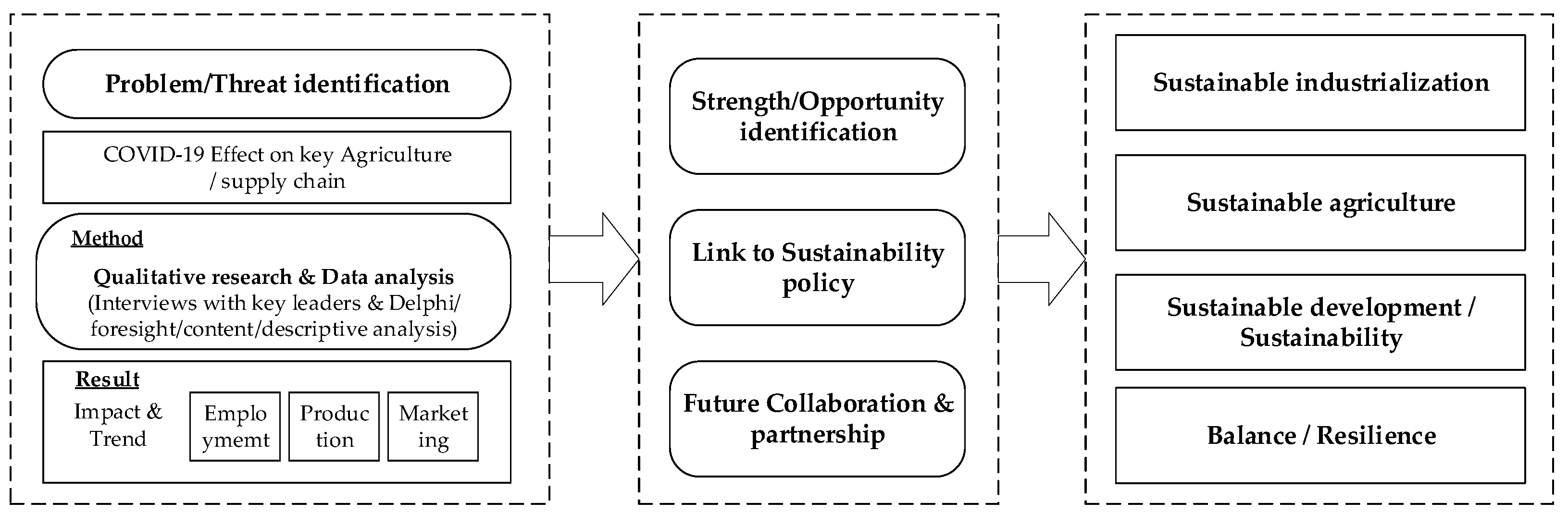

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Population and Sample

3.2. Data Collection

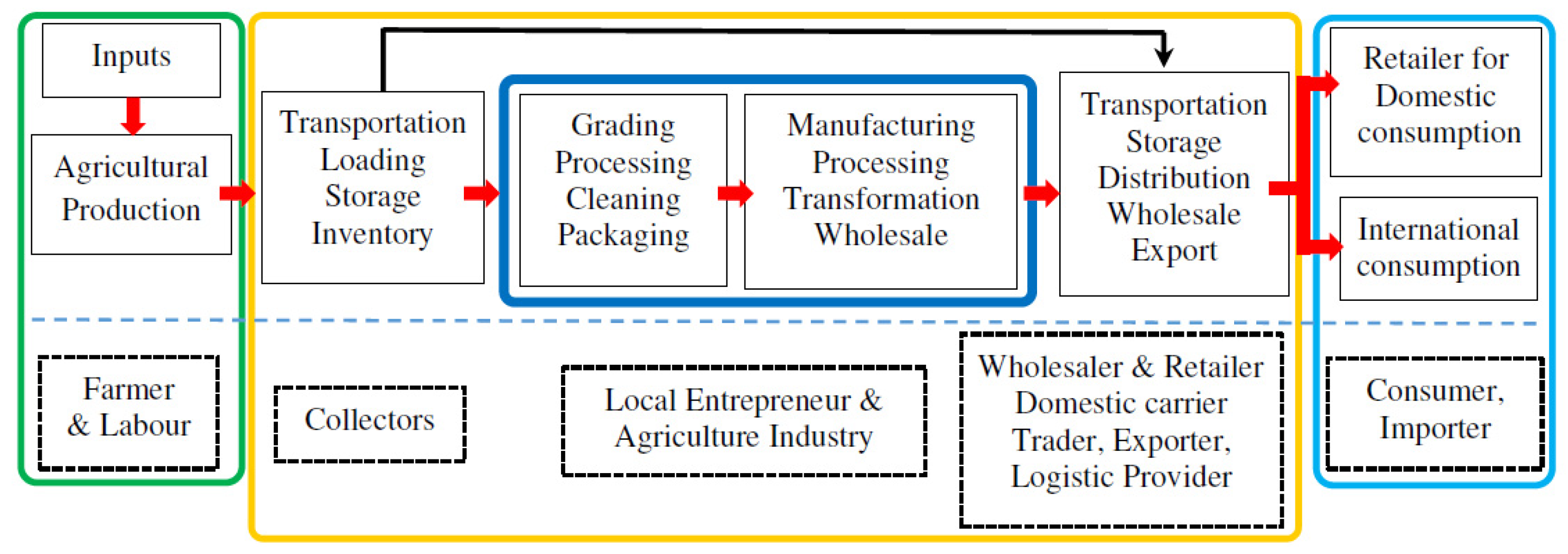

3.3. Research Scope

- -

- Upstream: Thai Agriculturist Association, Agricultural Cooperative;

- -

- Midstream: Thai Rice Millers Association;

- -

- Downstream: Thai Rice Exporters Association, Thai Rice Packers Association.

4. Analysis of Impact of COVID-19 on Agricultural Sector

4.1. ASEAN Agriculture Background

4.2. Impact of COVID-19 on ASEAN Agriculture and SDG Mapping

4.2.1. Economic Dimension

4.2.2. Environmental Dimension

4.2.3. Social Dimension

4.2.4. COVID-19 Impacts on ASEAN Agriculture with UN SDG Mapping

- Economic impacts:

- Environmental impacts:

- Social impacts:

4.3. SWOT Analysis

4.3.1. Strengths

- ○

- The agriculture and food products of Thailand are good-quality and safe products with a strong quality-control system.

- ○

- Thai entrepreneurs are competitive and can invest both in the country and abroad.

- ○

- The agricultural product processing industry uses modern, up-to-date technology.

- ○

- Thai farmers have high abilities and agricultural skills.

- ○

- Thai farmers and entrepreneurs have strong establishments in the private sector and partnerships with agriculture product associations for information exchange and problem-solving capabilities, such as the Thai Agriculturist Association, Rice Exporters Association, and Thai Rubber Association.

- ○

- The government sector pays good attention to small-scale agricultural entrepreneurs.

- ○

- Good cooperation exists between countries, (i.e., ASEAN member states) and international institutions (i.e., FAO).

4.3.2. Weaknesses

- ○

- Labor shortage and high labor costs.

- ○

- Small entrepreneurs are not yet strong, requiring more knowledge and understanding about business development, production and marketing, and proper technology utilization to achieve standardized outputs.

- ○

- Systems for tracing the product origins are not yet available for all products, especially plants.

- ○

- The cost of installing and deploying technology and innovation is high and burdensome for entrepreneurs.

- ○

- Thai agricultural products are dependent on export markets and are subject to global demand fluctuation and unstable world market prices.

4.3.3. Opportunities

- ○

- The COVID-19 pandemic changed consumers’ lifestyles and increased the demand for food safety and healthy agricultural food products. This coincides with the higher demand for agricultural and food products as the world population increases.

- ○

- The concepts of the New Theory for agriculture based on the Sufficiency Economy Philosophy integrated agriculture, precision agriculture, and the BCG (bio-circular-green) economy are opportunities to raise productivity levels and change agricultural production structures and systems.

- ○

- Technological advances, Internet systems, and “Big Data” are important opportunities for further development of Thai agricultural systems.

- ○

- E-commerce and online food-delivery platforms enable consumers to gain more access to agricultural and food products, allowing direct contact with the original sources or producers.

- ○

- The FAO publication “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020: Transforming food systems for affordable healthy diets” [33] provides timely advice for countries seeking to make the best of the situation at hand.

4.3.4. Threats

- ○

- The mechanisms of international trade are increasingly complex.

- ○

- There is a growing number of non-tariff restrictions and trade barriers, such as food safety and nutrition measures.

- ○

- Climate change.

- ○

- Delays in the recovery of the global food supply chain.

- ○

- Delays in the recovery of the world economy.

4.4. Evidence and Applications Based on the Agriculture Sector from Thailand to ASEAN

4.4.1. Production

- -

- Cassava and its products:

- ○

- A decrease in the exportation of cassava and its products owing to lower outputs and slow imports from China (Thailand’s main trading partner), due to limited logistics and transportation problems.

- -

- Longan:

- ○

- Because of the COVID-19 outbreak in China, products could not be shipped there. Many Chinese and Vietnamese importers and agents could not come to Thailand to negotiate purchases of fresh longans as usual.

- -

- Rice:

- ○

- The price of rice increased because of an increasing demand for rice, both from the domestic consumption and stocking up for the self-quarantine periods, and from increasing export orders. Thailand’s rice exports increased in demand as Vietnam restricted rice exports. However, there were some negative consequences based on the demand and supply of the market.

- -

- Rubber:

- ○

- Rubber prices dropped because of an increase in the supply from rubber production. The demand for raw rubber sheets from major trading partners also decreased because of the COVID-19 pandemic and the slowing global demand for automobiles and tires. In addition, the closure of the border checkpoints between Thailand and Malaysia resulted in delays in importing raw rubber materials.

- -

- Cassava and its products:

- ○

- In the second quarter of 2020, the cassava price index fell compared with the same quarter of 2019 because of the slowdown in the export of Thai cassava to China, the main trading partner, due to the epidemic situation.

4.4.2. Agriculture Markets and Logistics

4.4.3. Agricultural Labor

4.4.4. Households

4.4.5. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Thai Agricultural Products: A Case Study of Rice

- High production and export: Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos.

- Low production and high export: Singapore and Brunei Darussalam.

- Insufficient rice production for consumption: Singapore, Philippines, and Malaysia.

4.4.6. ASEAN and Rice as Food Security

5. Opportunities for Transformative Recovery and Regional Sustainability Strategies in Agriculture

5.1. Seeking New Opportunities to Strengthen Cooperation in the ASEAN Region’s Strategy in Agriculture

5.2. Promoting Strategies for Inter-ASEAN Trade Cooperation in the Agricultural Sector

6. Policy Suggestions

6.1. Build Common Agricultural Development within ASEAN

- ▪

- Tier 1 involves the release of earmarked emergency rice reserves under prearranged terms for anticipated emergencies;

- ▪

- Tier 2 involves the release of earmarked emergency rice reserves under other agreements for unanticipated emergencies not addressed by Tier 1;

- ▪

- Tier 3 involves the release of stockpiled emergency rice reserves under the contribution for severe emergencies and humanitarian responses, such as poverty alleviation and malnourishment eradication, to ensure food security in the region [29].

6.2. Increase the Efficiency of Water and Watershed Management

6.3. People-Centered (Putting People First)

6.4. Sustainable System

6.5. Resilience

6.6. Dynamic and Innovative Provision of Social Services and Health Care

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Department of ASEAN Affairs. Complementarities Roadmap (2020–2025). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Thailand. 2020. Available online: https://asean.mfa.go.th/en/content/117008-complementarities-roadmap-(2020-%E2%80%93-2025)?cate=5f2063650b09246d9a00a7cf (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- WHO. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard with Vaccination Data; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://covid19.who.int (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/publications/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development-17981 (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Chantarat, S. How Will the Thai Agricultural Landscape Transform towards Sustainable Development? Puey Ungphakorn Institute for Economic Research: Bangkok, Thailand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J.K.; Weiss, M.A.; Schwarzenberg, A.B.; Nelson, B.M.; Sutter, K.M.; Sutherland, M.D.B. Global Economic Effects of COVID-19; R46270; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Kanu, I.A. COVID-19 and the economy: An African perspective. J. Afr. Stud. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 3, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- The ASEAN Secretariat. ASEAN KEY FIGURES 2019; ASEAN Secretariat: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Department of International Trade Promotion, Ministry of Commerce, Thailand. China Trade Situation and Trade Opportunity Report; Department of International Trade Promotion, Ministry of Commerce: Bangkok, Thailand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Siche, R. What is the impact of COVID-19 disease on agriculture? Sci. Agropecu. 2020, 11, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- OECD. OECD Scheme for the Application of International Standards for Fruit and Vegetables. In Preliminary Report: Evaluation of the Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) on Fruit and Vegetables Trade; TAD/CA/FVS/WD: Paris, France; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Trade Map. Export&Import Statistic. 2021. Available online: http://www.trademap.org (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Aday, S.; Aday, M.S. Impact of COVID-19 on the food supply chain. Food Qual. Saf. 2020, 4, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Bank East Asia and Pacific Economic Update, April 2020: East Asia and Pacific in the Time of COVID-19; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, B.; Zhang, S.; Yuan, L.; Chen, K.Z. A balance act: Minimizing economic loss while controlling novel coronavirus pneumonia. J. Chin. Gov. 2020, 5, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pulubuhu, D.A.T.; Unde, A.A.; Sumartias, S.; Sudarmo, S.; Seniwati, S. The Economic Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak on the Agriculture Sector. Int. J. Agric. Syst. 2020, 8, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Nimsai, S. COVID-19 Impacts and Sustainability Strategies for Regional Recovery in Southeast Asia: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2020, 13, 8907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.R.; Malone, T.; Schaefer, A.K. Economic Impact of COVID-19 on Michigan Agricultural Production Sectors; No. 1098-2020-812; Miscellaneous Publications: Jackson, MS, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Espitia, A.; Rocha, N.; Ruta, M. Covid-19 and food protectionism: The impact of the pandemic and export restrictions on world food markets. World Bank Policy Res. Work. Pap. 2020, 1, 9253. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Kim, S.; Park, C.Y. Food Security in Asia and the Pacific amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. © Asian Development Bank. 2020. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11540/12119 (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Glenn, G.; Rico, A.; Rico, A. Assessing the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Agricultural Production in Southeast Asia: Toward Transformative Change in Agricultural Food Systems Assessing the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Agricultural Production in Southeast Asia: Toward Transformative Change in Agricultural Food Systems Commercialization and Mission Drift in Microfinance: Implications for Rural. Asian J. Agric. Development. 2020, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronavirus-19 Disease Epidemic Situation Administration Center. Available online: https://www.moicovid.com/ (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- CBC’s Journalistic Standards and Practices. Singapore Migrant Workers Deal with Anxiety as Living Quarters Become COVID-19 Cluster. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/singapore-s11-dorm-coronavirus-1.5539303 (accessed on 23 November 2020).

- CAN. Malaysia to Enter ‘Total Lockdown’ from June 1 to June 14 as Daily Number of COVID-19 Cases Hits New Record. Available online: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/asia/malaysia-total-lockdown-jun-1-14-muhyiddin-covid-19-cases-record-1417801 (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Philippines COVID-19 Response Plan. COVID-19 Humanitarian Response Plan Philippines. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/philippines/philippines-COVID-19-humanitarian-response-plan-final-progress-report-june-2021 (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Xinhua. Lockdown Extended in Laos as COVID-19 Cases Continue to Rise. Available online: http://www.news.cn/english/2021-09/30/c_1310220370.htm (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- The Star. Brunei Bars Residents from Leaving as Coronavirus Cases Reach 50 (Update). Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20200317093728/https://www.thestar.com.my/news/regional/2020/03/15/brunei-bars-residents-from-leaving-as-coronavirus-cases-reach-50-update (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Wikipedia. COVID-19 Pandemic in Cambodia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19_pandemic_in_Cambodia#cite_note-84 (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Wikipedia. COVID-19 Pandemic in Myanmar. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19_pandemic_in_Myanmar (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Gardaworld. Vietnam: All Foreigners Temporarily Banned from Entering the Country March 22/update 17. Available online: https://www.garda.com/crisis24/news-alerts/325836/vietnam-all-foreigners-temporarily-banned-from-entering-the-country-march-22-update-17 (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Department of International Trade Promotion, Ministry of Commerce, Thailand. Cambodia Introduced Measures to Ban the Export of White Rice and Paddy to Maintain the Country’s Food Security; Department of International Trade Promotion, Ministry of Commerce: Bangkok, Thailand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Bunditsakulchai, P.; Zhuo, Q. Impact of COVID-19 on Food and Plastic Waste Generated by Consumers in Bangkok. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveena, S.M.; Ahmad, Z. The impacts of COVID-19 on the environmental sustainability: A perspective from the Southeast Asian region. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 63829–63836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020. In Transforming Food Systems for Affordable Healthy Diets; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. Available online: https://doi.org/10.4060/ca9692en (accessed on 25 September 2021). [CrossRef]

- Kasikornresearch. Food Delivery in 2022 Continues to Expand Application Service Provider Invades Upcountry Areas to Expand New Customer Base. Available online: https://www.kasikornresearch.com/th/analysis/k-econ/business/Pages/Food-Delivery-z3289.aspx (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Siamwalla, A. Security of Rice Supplies in the ASEAN Region. In Food Security for Developing Countries; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Department of International Trade Promotion, Ministry of Commerce, Thailand. Overview of the Rice Market in ASEAN; Department of International Trade Promotion, Ministry of Commerce: Bangkok, Thailand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Arunmas, P. Rice Packers: Prices to Climb for Months. Bangkokpost. 23 March 2020. Available online: https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/1884290/rice-packers-prices-to-climb-for-months (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Prachachat. Covid Shakes the World Rice Market in 4 Countries, Slowing Down Sales of “Prices Go Up”. Available online: https://www.prachachat.net/economy/news-444449 (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Reuters. Malaysia Has Rice Stocks for 2.5 Months as Vietnam Curbs Exports. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-malaysia-food-idUSL4N2BK2K8 (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Malaysiakini. Malaysia Has Rice Stock for 2.5 Months as Vietnam Curbs Exports. Available online: https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/517258 (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rapid Assessment of the Impact of COVID-19 on Food Supply Chains in the Philippines; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-133791-2. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Agriculture, Philippine. DA Welcomes DTI’s Decision to Drop PITC Rice Import Plan. Available online: https://www.da.gov.ph/da-welcomes-dtis-decision-to-drop-pitc-rice-import-plan/ (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Reuters. Vietnam Jan-May Rice Exports up 12.2% y/y to 3.09 Monotones—Customs. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/vietnam-rice-idAFL4N2DO1LJ (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Xinhua. Cambodia’s Rice Export to China up 23.6 pct. in Jan–May. Available online: https://english.news.cn/asiapacific/20220604/e389ec9b4b4544859df466f1095bdedc/c.html (accessed on 4 June 2022).

- Foreign Agriculture Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Burma—Rice Export Policy Updates during COVID-19; Foreign Agriculture Service, United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chainani, D.G.; Farn, C.S.; Gomez, C.D.; Han, D.; Ziyong, G.; Loh, J.; Justin, K.J. COVID-19 & the Little Red Dot–Important Lessons for Trade in Times of Global Pandemics based on Singapore’s Experience. Available online: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/2048522/covid-19-the-little-red-dot/2801613/ (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Asean Information Center. Transition toward Thailand 4.0 through the Sufficiency Economy Philosophy. Available online: http://www.aseanthai.net/english/ewt_news.php?nid=1612&filename=index (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Diaz-Caneja, M.B.; Conze, C.G.; Dittmann, C.; Pinilla, F.J.G.; Stroblmair, J. Agricultural Insurance Schemes; Office for Official Publications of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/WHO-COVID-19-global-data.csv (accessed on 29 September 2021).

| Country | Total | Affordability | Availability | Quality and Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cambodia | 53.0 | 68.8 | 48.7 | 44.3 |

| Indonesia | 59.2 | 74.9 | 63.7 | 48.5 |

| Lao PDR | 46.4 | 47.7 | 46.1 | 49.2 |

| Malaysia | 70.1 | 85.6 | 64.0 | 76.3 |

| Myanmar | 56.7 | 58.9 | 52.2 | 63.0 |

| Philippines | 60.0 | 74.3 | 53.9 | 61.5 |

| Singapore | 77.4 | 87.9 | 82.9 | 79.1 |

| Thailand | 64.5 | 81.8 | 57.3 | 59.5 |

| Vietnam | 61.1 | 68.9 | 60.4 | 64.3 |

| Country | Strengths 1 | Challenges 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Cambodia | 1. Change in average food costs 2. Urban absorption capacity 3. Volatility of agricultural production 4. Food safety 5. Agricultural import tariffs | 1. Gross domestic product per capita 2. Public expenditure on agricultural R&D 3. Protein quality 4. Dietary diversity 5. Micronutrient availability |

| Indonesia | 1. Presence and quality of food safety net programs 2. Nutritional standards 3. Change in average food costs 4. Volatility of agricultural production 5. Food safety 6. Proportion of population under global poverty line 7. Urban absorption capacity 8. Agricultural import tariffs 9. Food loss | 1. Public expenditure on agricultural R&D 2. Gross domestic product per capita 3. Protein quality 4. Dietary diversity |

| Lao PDR | 1. Change in average food costs 2. Urban absorption capacity 3. Food loss 4. Food safety 5. Volatility of agricultural production 6. Agricultural import tariffs | 1.Protein quality 2.Public expenditure on agricultural R&D 3. Gross domestic product per capita 4. Agricultural infrastructure 5. Dietary diversity |

| Malaysia | 1. Proportion of population under global poverty line 2. Presence and quality of food safety net programs 3. Access to financing for farmers 4. Nutritional standards 5. Change in average food costs 6. Food safety 7. Food loss 8. Urban absorption capacity 9. Volatility of agricultural production 10. Agricultural import tariffs | 1. Public expenditure on agricultural R&D |

| Myanmar | 1. Urban absorption capacity 2. Change in average food costs 3. Volatility of agricultural production 4. Food loss 5. Proportion of population under global poverty line 6. Agricultural import tariffs 7. Food safety | 1. Public expenditure on agricultural R&D 2. Gross domestic product per capita |

| Philippines | 1. Nutritional standards 2. Change in average food costs 3. Volatility of agricultural production 4. Urban absorption capacity 5. Food safety 6. Food loss 7. Proportion of population under global poverty line 8. Agricultural import tariffs 9. Presence and quality of food safety net programs 10. Access to financing for farmers | 1. Public expenditure on agricultural R&D 2. Gross domestic product per capita 3. Protein quality |

| Singapore | 1. Proportion of population under global poverty line 2. Agricultural import tariffs 3. Presence and quality of food safety net programs 4. Access to financing for farmers 5. Public expenditure on agricultural R&D 6.Food loss 7. Nutritional standards 8. Food safety 9. Change in average food costs 10. Urban absorption capacity 11. Gross domestic product per capita 12. Political stability risk 13. Agricultural infrastructure 14. Volatility of agricultural production 15. Micronutrient availability | |

| Thailand | 1. Presence and quality of food safety net programs 2. Access to financing for farmers 3. Food safety 4. Proportion of population under global poverty line 5. Change in average food costs 6. Food loss 7. Volatility of agricultural production 8. Urban absorption capacity | 1. Public expenditure on agricultural R&D 2. Gross domestic product per capita |

| Vietnam | 1. Presence and quality of food safety net programs 2. Access to financing for farmers 3. Change in average food costs 4. Proportion of population under global poverty line 5. Food safety 6. Volatility of agricultural production 7. Urban absorption capacity 8. Food loss | 1. Public expenditure on agricultural R&D 2. Gross domestic product per capita |

| Country | Main Agricultural Products | Major Export Agricultural Products |

|---|---|---|

| Brunei Darussalam | Rice, Milled | - |

| Cambodia | Oil, Peanut; Meal, Peanut; Oilseed, Peanut | Rice, Milled; Corn; Sugar, Centrifugal |

| Indonesia | Oil, Palm Kernel; Oilseed, Copra; Oil, Coconut; Meal, Copra; Rice, Milled; Coffee, Green; Oil, Peanut; Meal, Peanut; Oilseed, Peanut; Oilseed, Peanut | Meal, Palm Kernel; Oilseed, Copra; Oil, Palm Kernel; Oil, Palm; Meal, Copra; Oilseed, Palm Kernel; Oil, Coconut; Coffee, Green |

| Lao PDR | Oil, Palm Kernel; Oil, Peanut; Meal, Peanut; Oilseed, Peanut | Coffee, Green; Rice, Milled; Sugar, Centrifugal; Corn |

| Malaysia | Oil, Palm; Oil, Palm Kernel; Oilseed, Palm Kernel; Meal, Palm Kernel; Coffee, Green; Meal, Copra; Oilseed, Copra; Oil, Coconut | Oil, Palm; Meal, Palm Kernel; Oil, Palm Kernel; Oil, Coconut; Coffee, Green; Oil, Soybean |

| Myanmar | Oil, Peanut; Meal, Peanut; Oilseed, Peanut; Rice, Milled Oil, Cottonseed; Meal, Cottonseed; Millet; Oilseed, Cottonseed; Oilseed, Sunflower Seed; Cotton | Corn; Oilseed, Peanut; Cotton |

| Philippines | Oil, Coconut; Meal, Copra; Oilseed, Copra; Rice, Milled; Sugar, Centrifugal; Corn | Meal, Copra; Oil, Coconut; Sugar, Centrifugal; Oil, Palm Kernel |

| Singapore | Meal, Soybean; Oil, Soybean | Oil, Coconut |

| Thailand | Oil, Palm Kernel; Oil, Palm Kernel; Oilseed, Palm Kernel; Meal, Palm Kernel; Oil, Palm; Rice, Milled; Oilseed, Copra; Oil, Coconut | Oilseed, Palm Kernel; Rice, Milled; Sugar, Centrifugal; Oilseed, Copra; Oil, Palm Kernel; Oil, Soybean; Oil, Palm; Coffee, Green |

| Vietnam | Coffee, Green; Rice, Milled; Oil, Coconut; Oilseed, Copra; Meal, Copra; Meat, Swine; Oranges, Fresh; Oilseed, Peanut | Coffee, Green; Rice, Milled; Meal, Copra; Corn; Meal, Soybean; Oil, Coconut |

| Sustainability Pillar | Impact | Short Description | Links to SDGS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economy | Negative (-) | The outbreaks of COVID-19 have severely affected the economic dimension, including a decrease in the exportation of agricultural products and increase in value chain disruptions, to various extents. It also links to regression of UN SDG 2 and 8 in particular.

| SDG 2 (zero hunger), SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth) |

| Environment | Positive (+) Negative (-) | The COVID-19 pandemic has both positive and negative effects on the environment

| SDG 13 (climate action) SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production), SDG 14 (life on land) |

| Society | Negative (-) | The COVID-19 pandemic adversely affected the society in different degrees.

| SDG 1 (no poverty), SDG 2 (zero hunger), SDG 3 (good health and well-being), SDG 8 (decent work & economic growth), SDG 10 (reduce inequality). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tansuchat, R.; Suriyankietkaew, S.; Petison, P.; Punjaisri, K.; Nimsai, S. Impacts of COVID-19 on Sustainable Agriculture Value Chain Development in Thailand and ASEAN. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142012985

Tansuchat R, Suriyankietkaew S, Petison P, Punjaisri K, Nimsai S. Impacts of COVID-19 on Sustainable Agriculture Value Chain Development in Thailand and ASEAN. Sustainability. 2022; 14(20):12985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142012985

Chicago/Turabian StyleTansuchat, Roengchai, Suparak Suriyankietkaew, Phallapa Petison, Khanyapuss Punjaisri, and Suthep Nimsai. 2022. "Impacts of COVID-19 on Sustainable Agriculture Value Chain Development in Thailand and ASEAN" Sustainability 14, no. 20: 12985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142012985

APA StyleTansuchat, R., Suriyankietkaew, S., Petison, P., Punjaisri, K., & Nimsai, S. (2022). Impacts of COVID-19 on Sustainable Agriculture Value Chain Development in Thailand and ASEAN. Sustainability, 14(20), 12985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142012985