Abstract

Considering that the development of science and technology depends on metal support, the EU, USA, and China have issued a critical metal list on the development report. However, the scarce and important mineral deposits on a global scale will not be enough to meet the huge needs of economic development in the future. Many fields such as renewable energy, high-performance computing, and AI all require critical metals as essential supports. A proper price regulation of such important metals will contribute to the fair price power on the international market. In this paper, the pricing history and strategy of critical metal support are fully studied and discussed. Since China has become a major consumer country, China should gain fair price power in the market of important metals.

1. Introduction

Metal and minerals are the blood of the industry. The assured supply of critical materials and the resiliency of their supply chains are essential to economic prosperity and national security [1]. The United States (US) [2] and European Union [3] defined their own critical metal lists in 2017 and 2018, respectively. For example, the critical minerals in the US were defined by the 45th president Donald J. Trump, who issued Executive Order (EO) 13817, a federal strategy to ensure secure and reliable supplies of critical minerals [4].

The low-carbon development of China’s iron is important but challenging for the attainment of China’s carbon neutrality by 2060, which requires critical metals and minerals [5]. In addition to critical metals and minerals, other metals are also in high demand in China [6]. Today, China is the world’s largest importer of iron ore and copper, as well as an important importer of bulk commodities such as alumina [7] and nickel. China imports 100 million tons of iron ore each year. Since 2011, China has become highly dependent on imported iron ore, and its current dependence on international sources is about 80%. In terms of nonferrous metals, China became the world’s largest copper consumer as early as 2001, most of which had to be imported [8]. In 2008, it replaced Japan and became the largest copper concentrate importer. China is not only a major importer of many bulk commodities but also has a high degree of trade dependence on many resource commodities. Among them, the import dependence on crude oil, iron ore, alumina, and nickel are more than 50%. Some even reach more than 80% [9].

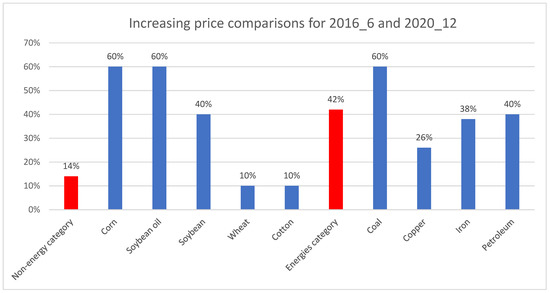

In June 2021, the mid-price international bulk commodity price index (December 2013 = 100) of the Price Monitoring and Compilation Center of the National Development and Reform Commission increased by 32% from December 2020 [10]. Figure 1 shows that the energy price index represented by observations rose by 42%, and the non-category prices represented by soybean, wheat, corn energy, and cotton rose by 14%. Specifically, the prices of soybean oil, coal, and coal rose by more than 60%. The prices of products have risen dramatically since December 2020. As a result of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, the current increase in commodity prices is mainly driven by market expectations [11]. On the one hand, the global economic recovery has brought about expectations of growth in commodity demand; on the other hand, the “uncapped” quantitative easing policy in the United States has spawned market concerns about excess liquidity, and the combined effect of the two has greatly increased the market’s expectations for later price increases. In addition, the short-term increase in the price of bulk commodities is due to the substitution of goods consumption for service consumption caused by the epidemic, as well as the suppression of the supply of basic commodities by the epidemic and the disturbance of the supply chain. In the long term, it may be affected by continuous supply contraction and the global carbon emission reduction wave. In addition, the imported inflation risk brought by the rapid increase in commodity prices this round is generally controllable. However, some issues, such as structural adjustment pressure caused by price increases, the risk of declining benefits, and the increase in uncertainty in the foreign trade situation, should be paid attention to [12].

Figure 1.

The percentage price increase of different products from June 2016 to December 2020. It shows that prices have been risen dramatically since December 2020.

In this article, the logic is organized as follows: Section 1 introduces China’s demand for the pricing power of bulk commodities; Section 2 introduces the reality of China’s lack of pricing power for bulk commodities; Section 3 discusses the proposed international bulk commodity pricing mechanism research; Section 4 introduces the basis of the pricing power of precious metals in bulk commodities; Section 5 introduces the relevant policies and regulations issued by China; and Section 6 presents concluding comments and suggestions on China’s influence on the pricing power.

China’s import volume and consumer demand for bulk commodities are so large that they have a significant impact on the international bulk commodity market. China currently consumes huge amounts of bulk commodities and has become the world’s largest consumer of a variety of bulk commodities. The import volume of bulk raw materials such as petroleum, iron ore, and copper [13] in China is very important. China should be able to influence the price trend of these commodities to a certain extent. Due to monopoly, international politics, and other reasons, the price decision is not dominated by supply or demand factors. The actual price increase of many commodities has greatly exceeded the reasonable range that reflects the relationship between supply and demand. Therefore, China has suffered huge economic losses [14].

China’s international market influence is currently reflected only in the demand-driven aspect. Enterprises participating in international market transactions have not yet obtained the dominance of the international commodity trading market. They have little influence on transaction prices and can only passively accept international market prices. In 1 year, the average price of imported commodities in China rose by double digits, among which the import price of iron ore rose as high as 94.92 USD/t in 2019. China’s steel companies are forced to accept the increase of the imported iron ore price, with a total price of 100 million US dollars. In the upcoming years, as a major purchaser in the international market, China should obtain corresponding pricing power in the commodity market, but China’s influence on the international market is very limited due to the lack of regulation authority. “China needs whatever, the international market will rise” has become a consensus in the economic circle. China has suffered huge economic loss in the process of high volatility in international commodity prices, and the stability of the macroeconomy has also been severely affected, leading to a negative impact on China’s economy. Given such a background, it is of great importance for Chinese to fight for the pricing power of bulk commodities.

As a major importer of bulk commodities, it has important practical significance to study the lack of pricing power of bulk commodities in China. In this paper, we discuss the effects of the regulated metal and mineral prices in China. We introduce the present results of the metal and mineral commodities before the reform and describe trends of the reform of the pricing mechanism of international metal and mineral commodities. Then, we discuss the regulation effects in different countries. Finally, we propose the method of China’s metal and mineral futures market. We summarized the rules that China should follow in the future.

2. Methods

2.1. Current Situation and Problems

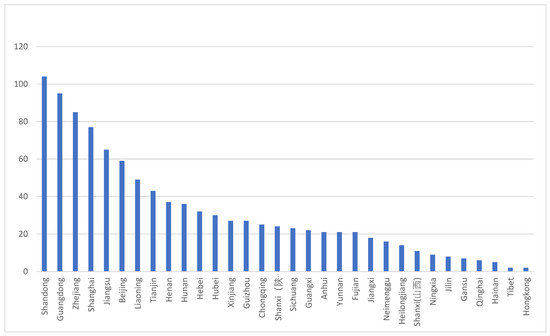

With nearly 30 years of rapid development, China’s metal and mineral futures market has effectively played an imported role in pricing and hedging, contributing directly to China’s real economy and the capital market. Figure 2 shows the market distribution in China. Take the recognized copper futures with the best market function as an example. The copper futures price of the Shanghai Futures Exchange (hereinafter referred to as the Shanghai Futures Exchange) has become the benchmark price in domestic copper spot trading. The copper futures price of the futures exchange is based on the benchmark price plus premiums and discounts. Many domestic copper upstream, midstream, and downstream companies are actively using the copper futures market to hedge and manage corporate price risks. However, in the international trade of copper, although China is the world’s largest producer and consumer of electrolytic copper, and the Shanghai price has had a great impact on the copper futures price of the London Metal Exchange (LME), the international trade benchmark price is still the LME price. It is difficult for international trade contracts to be priced with the copper futures price on the Shanghai Futures Exchange.

Figure 2.

Regional distribution of commodity exchanges in Chinese regions. Reproduced from: China Logistics and Purchasing Network, http://www.chinawuliu.com.cn accessed on 23 September 2021.

2.2. Solutions

Institutional obstacles restrict domestic futures prices from becoming the benchmark price in international trade. First, before China’s futures market is opened to the outside world, foreign entities and investors cannot directly participate in China’s market and the price formation process as well. Hence, it is difficult to use China’s prices to evaluate international trade activities. Second, due to the domestic tax system, the current domestic futures prices (except for crude oil, fuel oil, and No. 20 rubber futures) are all tax-inclusive prices. In this case, even if the supply and demand relationship and value of the product itself remain unchanged, the price of the product can change due to the adjustment of the domestic value-added tax and/or import tariff rate. Reflecting the change in the value of the commodity itself, it is only suitable for the pricing and settlement of domestic trade. However, it does not conform to international conventions, which makes it difficult to become the benchmark pricing for international trade.

3. Results

3.1. The Pricing Mechanism of Metal and Mineral Commodities before the Reform

London is currently the world’s largest gold and silver over-the-counter market. The silver fixing price is set at 12 noon every day. There are three pricing banks, namely, Deutsche Bank, HSBC USA London Branch, and The Bank of Nova Scotia-Mocatta. Gold is priced twice a day, at 10:30 am and 3 pm. The five pricing banks are Deutsche Bank, HSBC London Branch, Barclays Bank (Barclays Bank), Societe Generale (Societe Generale), and Scotiabank. Except for the different timings of the fixing prices of gold and silver, the principles are the same. Let us take the pricing of gold as an example to analyze the pricing mechanism of precious metals in London. The twice-daily pricing system for the London gold market began in 1919. On 12 September of that year, representatives of the five major banks in London gathered for the first time at the Rothschild Bank’s London office and began to formulate daily gold prices for the London gold market. This price system has continued to today. However, the pricing method for gatherings of the five major banks is now changed to conference calls. The five major pricing firms take turns as pricing chairpersons. Generally, market transactions stop for a while before pricing. At that time, the gold merchants first suspend their quotations, and the chairman will set an appropriate opening price based on the New York gold market price after the London market closed the day before and the Hong Kong gold market price in that morning. The representatives of the remaining four banks immediately declared the amount of gold bought and sold by their company accounts and their customers based on this opening price. If there are more buyers than sellers, the chairman will increase the price of gold and vice versa. The fixing price of gold is determined based on this supply and demand relationship and is quoted in U.S. dollars, pounds sterling, and euros. The length of time for pricing depends on market supply and demand. It can be as short as 1 min or as long as 1 h. The prices of silver, platinum, and palladium are also determined in the same way. After the fixing price is determined, traders issue new trading instructions to buy and sell gold based on the fixing price announced by the London Gold Market Pricing Company.

Because the five major pricing houses have extensive connections with many gold mines and manufacturers in the world, their trading volume accounts for approximately 70% of the global precious metal trading volume. Therefore, the fixed price that they finally determine by continuously reporting the gold buying and selling price is very authoritative and is widely used as the benchmark price for gold spot, forward, and various over-the-counter derivative transactions.

3.2. The Shortcomings of the Pricing Mechanism for Metal and Mineral Commodities before the Reform

In the past 100 years, due to the long history of the London precious metals market, the London gold and silver fixing price has always been an important benchmark price and has played a pivotal role. However, with the development of information technology, the traditional manual pricing mechanism has gradually lost its advantages of openness and transparency, and its drawbacks have gradually become prominent.

3.2.1. The Pricing Bank Has a Conflict of Interest during the Fixing Process

Pricing banks not only set prices for gold and silver but are also major participants in the global precious metals market. This gives pricing banks a huge incentive to influence benchmark prices based on their trading positions, resulting in many insiders trading. At the same time, some pricing banks have begun to carry out high-frequency trading in the precious metals market. They use inside information to obtain huge profits in a very short time. The role of pricing firms as both referees and athletes has been widely criticized by the market.

3.2.2. The Fixing Process Is Not Open or Transparent

The pricing bank finalizes the price by means of a conference call and does not announce any quotation and order volume data during the fixing process but directly announces the final fixing price. In this case, the outside world has no way to obtain any data during the fixing process. It is difficult for regulators to review the fixing process and difficult to investigate whether the fixing price is manipulated. For example, the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) once suspected that some major international investment banks manipulated the price of silver and launched a 5-year investigation. However, no solid evidence has been found thus far.

3.2.3. Lack of Supervision during the Fixing Process

According to statistics, the global precious metals market has a trading scale of up to US $20 trillion per year. Given such a huge market, the benchmark price was determined by a few companies with direct economic interests through telephone communication with private information and without proper supervision. For example, London gold and silver market pricing companies publish gold- and silver-fixing prices every day free of supervision by any institution. Although there is no definitive evidence that the pricing banks manipulated the London gold and silver fixing prices, for the sake of huge profits, the pricing banks may have the motivation to manipulate the pricing process.

3.3. Reasons and Trends of the Reform of the Pricing Mechanism of International Metal and Mineral Commodities

3.3.1. Reasons for the Changes in the Pricing Mechanism of International Metal and Mineral Commodities

The London precious metal fixing price mechanism, which has been in operation for nearly 120 years, has now had to undergo profound changes. There are inherent shortcomings of the fixing price mechanism driven by external regulatory pressures.

Deutsche Bank Withdrew from the London Gold and Silver Pricing Seat

Deutsche Bank is one of the largest participants in the commodity market among investment banks and one of the most authoritative institutions for financial asset pricing. With the formal implementation of the “Dodd-Frank Act”, Deutsche Bank began to shrink its commodity business across the board.

In 2012, Deutsche Bank was accused of manipulating the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) and the Eurozone Interbank Offered Rate (EURIBOR). On 4 December 2013, the European Commission decided to impose a fine of EUR €1.71 billion (approximately US $2.3 billion) on eight international financial institutions that participated in manipulating financial market lending rates. Among them, Deutsche Bank fined 725 million euros (approximately 980 million US dollars), ranking first among all banks. After the EU resolution, Deutsche Bank will also wait for the results of investigations or penalties by regulatory authorities in the United States, Asia, and other places on related interest rate manipulation. In addition, Deutsche Bank is facing related investigations and/or lawsuits in fields such as foreign exchange transactions and credit default swap transactions. In the face of huge external pressure, on 17 January 2014, Deutsche Bank announced that it would withdraw from the London gold and silver pricing seat and no longer participate in the London gold and silver benchmark price-fixing process. According to regulations, there should be no less than three pricing members for the London silver fixing price. The withdrawal of Deutsche Bank and the difficulty in finding a suitable replacement in time have ultimately led to a situation where the silver fixing price mechanism cannot function normally. Mechanism reform is imperative.

Supervision Has Become Increasingly Strict

After the London Interbank Offered Rate (Libor) manipulation case broke out, the US and European financial regulatory authorities increasingly paid close attention to the fixing prices of gold and silver and continuously increased their supervision of the gold and silver market. In November 2013, the British Financial Market Conduct Authority (FCA) launched a preliminary investigation into the possible London gold fixing price insider trading case. The banks under investigation include the five major gold pricing banks. The London gold fixing price system has thus been subject to strong market doubts and shocks. On 23 May 2014, the FCA issued a statement stating that it had decided to impose a fine of approximately £26 million pounds on Barclays Bank due to the manipulation of the London gold pricing mechanism by the former Barclays Bank. This is also the first time the global precious metals market has been punished due to a manipulation scandal. Increasing regulatory pressure and Deutsche Bank’s withdrawal from the pricing bank have undoubtedly put the London gold and silver fixing price mechanism, which has been in operation for a hundred years, in a precarious situation.

Electronation Has Become the General Trend

Technically speaking, the London gold and silver fixing price mechanism is a kind of matching transaction that adopts the law of large numbers and is formulated according to the status of several major pricing houses. Currently, computer technology is very advanced, and electronic trading is widely used, which can eliminate the control of fixing prices in the hands of several major investment banks. Using electronic trading methods for reference, matching all supply and demand in the market, the price obtained by the matching will make the market more convincing.

At present, in addition to gold, silver, platinum, and palladium, basic metals such as copper, aluminum, lead, zinc, tin, nickel, crude oil, and agricultural commodities have all achieved transparent pricing and trading mechanisms through electronic trading platforms. The London Metal Exchange (LME) is a globally recognized base metal pricing center, the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) under the CME Group is a global agricultural product pricing center, the New York Mercantile Exchange under the CME Group (The New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) is the global crude oil pricing center, and the Shanghai Futures Exchange (SHFE) is also one of the world’s three largest copper pricing centers.

3.3.2. Trends in the Reform of the Pricing Mechanism of International Metal and Mineral Commodities

After Deutsche Bank announced its withdrawal from the London Bullion Pricing Bank seat, the LBMA initiated consultations with its members, seeking to find a better London daily silver price mechanism. After summarizing the opinions of the market, the LBMA believes that the new silver pricing mechanism must be transparent, determined by auction, electronically, and auditable. In addition, more direct participants can be involved.

New Silver Pricing Mechanism Plan

In May 2014, the LBMA issued an announcement to the world, looking for an alternative solution for the silver pricing system. Subsequently, several institutions submitted bidding proposals. On 20 June 2014, the LBMA held a seminar on alternative solutions, and 7 institutions presented their solutions to market participants such as miners, banks, and jewelers. On 11 July 2014, the LBMA announced that the Chicago Mercantile Exchange Group and Thomson Reuters will provide a new pricing mechanism to replace the 117-year-old London silver fixing price. In terms of the division responsibilities for the new pricing mechanism, the CME Group will provide a pricing platform and algorithms for daily transaction processing, and Thomson Reuters will be responsible for administrative management and governance. Unlike the three major investment banks that originally participated in pricing, the CME Group is the world’s largest futures exchange, and Thomson Reuters is an information service provider. It is also possible to participate in the transaction for price manipulation.

The Trend of Future Changes in the Gold Fixing Price Mechanism

After the London silver fixing price mechanism officially withdrew from the stage of history in mid-August, the London gold fixing price mechanism, which has been in operation for 100 years, also ushered in changes at the end of 2014.

On 16 July, the London Gold Market Pricing Company and the LBMA jointly issued a statement stating that the screening process for finding new managers for the London gold fixing price will be launched in late August and will last for 1 month. LBMA stated that it welcomes all third-party organizations that are interested in participating in the public opinion consultation before the end of August and plans to announce the selected third-party organizations at the end of September. The new gold pricing mechanism will be officially implemented before the end of this year. In early July, the World Gold Council convened 34 representatives from central banks, investment banks, gold miners, gold ETF fund companies, exchanges, and industry institutions to hold a roundtable meeting to reach a consensus on the current fixing price reform plan, including the further expansion of the degree of participation in the pricing process and the separation of market making and benchmark management. The detailed plan for the choice of future gold pricing mechanism is expected to be announced by the LBMA.

4. Discussion

As a kind of international economic “power”, the international pricing regulation of metal minerals can also be analyzed and explained based on the theory of structural power. We will start from the four aspects of the sources of structural power and explain how structural power helps the country obtain the international pricing power of bulk commodities.

4.1. Production Structure and International Pricing Power for Metal Minerals

The status of a country’s enterprise in the global production structure and its impact on pricing power can be measured by the enterprise’s international market concentration index. According to the market structure theory of economics, in a perfectly competitive market structure, enterprises are the price takers of market prices, and their pricing power is the lowest. With the expansion of production and operation scale and the increase of market concentration, the monopoly position of enterprises in the market gradually increases (from monopolistic competition to oligopoly), and the market pricing power will be enhanced accordingly. Under a completely monopolistic market structure, the firm’s pricing power can reach the maximum. In other words, it will become the only price maker.

4.1.1. Concentration of Supply in the International Market

The concentration of supply in the international market refers to the proportion of a company’s output in the industry’s total global output. The higher the supply concentration of an enterprise is, the higher the pricing power an enterprise will gain. Taking the international iron ore market as an example, based on the advantages of domestic iron ore resources and the results of long-term market competition, the current international iron ore market is largely controlled by BHP (BHP Billiton), RIO (Rio), AVLE (Vale), and FMG. The oligopoly structure of four major miners includes the concentration of supply in the international market of the above four iron ore mining companies (CRJ has well exceeded the 30% monopoly threshold, and as of 2018, this indicator is as high as 50.88%). Such a production structure of power supports the price influence recognized by the four major miners. As a strong proof, in the 2005 international iron ore long-term agreement pricing negotiations, the oligarchic supplier alliance composed of the four major miners forced Chinese and foreign steel companies to accept the bitter fruit of a huge price increase of 71.5% [15].

Beginning in the 1880s, the international crude oil market has gone from being dominated by the American Standard Oil Company (a single company’s international market supply concentration was as high as 85%) to the “three oligarchs” monopoly (Standard Oil Company, British-Polish Company, and Exxonmobil Company) at the end of the 19th century. Petroleum Company and Royal Shell Petroleum Company joined the competition of the “Seven Sisters” oligarchs in the first half of the 20th century. The crude oil production of the “Seven Sisters” peaked in 1952 and once accounted for 90% [16] of the world’s oil production. In line with this, an indisputable fact is that the price of the international crude oil market has been controlled and dominated by the “seven sisters” oil oligarchs for a long time. After World War II, marked by the rise of national oil companies in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, oligarchic competition emerged again. In 2015, the “New Seven Sisters” international market supply concentration exceeded 37.6% and remained so. As a result, the national oil company’s overall pricing position in the current international crude oil market has been significantly improved [17].

4.1.2. Concentration of International Market Demand

In addition to supply, demand also constitutes another core aspect of the production structure. Companies worry about the high degree of market demand concentration, namely, the company’s procurement (demand) has a high ratio of the global procurement (demand) of the commodity. This structural power of production supports the price influence recognized by the four major miners. The proportion can also give enterprises structural power and corresponding pricing influence. For example, as a major downstream industry that has procurement requirements for iron ore, the industrial concentration of China’s steel industry was once very low. In 2016, the domestic market concentration (CR3) level of the top three steel companies on China’s production scale was only 17.72%. As a result, the demand concentration of Chinese steel companies in the international iron ore market is also relatively low. Decision-making in procurement negotiations is scattered and independent, making it difficult to form sufficient negotiating pressure on oligarchic miners. On the other hand, in Japan, South Korea, Brazil, and many other countries, the domestic industry concentration CR3 of the top three steel companies in their respective production scales is as high as 79.88%, 94.8%, and 76.9% [18], respectively. Correspondingly, countries such as Japan and Korea dominate international iron ore procurement pricing negotiations.

4.1.3. Circulation Concentration in the International Market

In addition to the supply and demand level, the concentration of international market circulation, namely, the proportion of the company’s bulk commodity transportation and sales in the total global transportation and sales of the bulk commodity, has become the third key indicator that can measure the structure of the company’s production. The structural power and pricing influence was brought about by the concentration of international market circulation.

4.2. Financial Structure and International Pricing Power for Metal and Mineral Commodities

The impact of financial structural power on the international pricing power of metal and mineral commodities is mainly reflected in the following three aspects:

First, a country’s currency becomes the main currency for the valuation and settlement of metals and minerals. If a country’s currency can become the main currency for valuation and settlement, the country can influence the international market prices of metals and minerals through domestic fiscal and monetary policy channels. “Domestic fiscal and monetary policy-the stock of currency denominated in the international market-international economic expansion or contraction-metal mineral supply and demand-international market price changes” is the “currency status-pricing power” mechanism. The best performance in this regard is undoubtedly the US. An empirical study by some scholars found that there is a significant correlation between changes in US domestic economic policies and the prices of international metal and mineral commodities [19]. In short, with the absolute dominance of the US dollar in the international monetary system, the US can influence the international prices of metal and mineral commodities through domestic monetary and economic policies.

Moreover, a country’s financial institutions can provide financing support for the production, supply, and marketing of metal and mineral commodities. The dominant international credit monopoly held by a country’s financial institutions can not only enable relevant companies to obtain sufficient capital advantages in market price games but also help related companies. Enterprises have won a more favorable position in the production structure in the international market. Take the iron ore industry as an example. Currently, several major oligarchs have close relationships with international financial institutions. Public information shows that the top shareholders of RIO (Rio Tinto) and BHP (BHP Billiton) include HSBC, JP Morgan, Australian Investment Fund, Citibank, and other internationally renowned financial institutions. In addition to national financial institutions such as the National Development Bank of Brazil, the main shareholders of Vale (Vale) also appeared in Japan’s Mitsui Group.

Finally, the National Metal Mineral Commodity Futures Market has become an international pricing center.

Since the beginning of the new century, under the background of financial liberalization and financial innovation and development, various financial institutions represented by futures investment funds have entered the commodity futures market for arbitrage trading [20,21,22]. As a result, the current international market prices of bulk commodities not only depend on the physical supply and demand but are increasingly affected by market arbitrage transactions. In that case, the countries where the major commodity futures markets are located will exert influence on international market prices by means of their privileges and conveniences in the formulation of trading rules and the choice of trading currencies.

4.3. Knowledge Structure and International Pricing Power for Metal and Mineral Commodities

The influence of the knowledge structure on the pricing power of bulk commodities has the following two paths. First, the breakthrough and application of bulk commodity production and development technology can change the existing production structure (market concentration) of the bulk commodity and then make technological breakthroughs. Countries obtain market pricing power, such as the “shale oil and gas revolution” in the US. The United States has long been the largest importer of energy commodities such as crude oil and natural gas. Second, the monopoly of a country’s enterprises or related institutions in the acquisition, processing, and release of bulk commodity market information can enable relevant countries to have a strong international price guide.

4.4. The Impact of the Security Structure on the International Pricing Power of Bulk Commodities

The mechanism of the security structure’s effect on the international pricing power of bulk commodities mainly lies in the fact that a country can indirectly affect the production, supply, and marketing situation of a certain commodity by controlling the geopolitical security situation related to the supply of bulk commodities and then obtain international pricing power.

5. Policy Regulations and Implications

We should realize that internationalization is not an end, to some extent, to achieve development goals. Our goal is to increase the international participation of China’s futures market through the internationalization of the futures market and to promote the gradual development of China’s futures prices into a pricing benchmark for international trade. Therefore, it is important for China to enhance the pricing influence and voice in the international bulk commodity market.

Firstly, it is necessary to adopt an attitude of seeking truth from facts and specific analysis of specific issues and adopt different methods to achieve internationalization according to the specific conditions of different commodity spot markets. The existence of the two domestic and international spot markets has caused one-way flow and artificial separation. Based on retaining the existing tax-containing contract transactions, net futures contracts should be launched to cover the bonded market and the international market and to participate in the main body’s domestic market. Based on the direct introduction of foreign investors, we will strive to establish the net price contract as a pricing benchmark for international trade.

Secondly, given the success of launching the net price contract, it is important to set up overseas delivery warehouses, preferably Korea, Singapore, and other places in Asia, and then focus on the countries along the “Belt and Road”, and finally expand the delivery warehouse network to the US and Europe. Traditionally developed markets realize the international allocation and global delivery of resources.

The third is to promote the overseas registration of domestic futures exchanges. Overseas registration will inevitably bring about the long-arm jurisdiction of overseas regulatory agencies, but overseas registration is unavoidable for China’s futures market to attract foreign investors and achieve internationalization. The order of overseas registration can be registered in the order of Hong Kong, Singapore, EU countries, and the US.

Fourthly, it is recommended to actively explore business cooperation with overseas exchanges. To effectively enhance the influence and price radiation of domestic futures exchanges, cooperation models such as settlement price authorization, interconnection, and equity cooperation with overseas exchanges can be considered. The international layout of domestic futures exchanges can be quickly promoted through complementary advantages.

Fifthly, improving laws and regulations, in accordance with international practices, requires overseas exchanges that attract Chinese institutions and investors to participate in transactions. It is important to register with Chinese regulatory agencies and implement long-arm jurisdiction over overseas exchanges to protect domestic institutions and investments. It is necessary to research and promulgate China’s metal and mineral commodity spot trading laws and regulations, and establish a multilevel and diversified supervision system as soon as possible. Because the spot market for metal mineral commodities plays an important role in price discovery and the reduction of transaction costs, speeding up the promulgation of laws and regulations, regulating the spot market transactions of metal mineral commodities, and clarifying the functions and responsibilities of supervisory departments are needed to standardize the metal mineral commodity trading market. The deepening of activities is also a practical measure to promote the healthy development of the metal mineral commodity market, which is of great significance.

Finally, relevant government departments must consider issues from the perspective of the overall national interests, discard departmental thinking and departmental interests, and contribute strategic wisdom to the long-term development of China’s economy. At the same time, the state should adopt policies to encourage enterprises in the same industry to merge and reorganize, support leading enterprises that are influential in the international trade of bulk commodities, form leading industry alliances in the bulk commodity market, and exert concentrated price influence in international trade negotiations. Moreover, the government must also lead the establishment of important resource storage systems, early warning mechanisms, and information systems. According to the domestic price fluctuations, it must carry out a moderate procurement plan for metal mineral raw materials in the international market and then form a certain number of raw material reserves. Additionally, China must carry out relative hedging and look for opportunities to buy commodities on the futures market to provide resources for domestic commodities. Functional agencies should also establish and disclose various related information and provide effective and timely commodity information to share with enterprises and investors. Combining the changes in international politics and economy encourages research institutions, industry associations, and scientific research institutions to study and analyze the changes in the supply and demand of commodities and price fluctuations. Only in this way can the weakness of domestic enterprises in this area be gradually eliminated.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed an effect of regulation problems on the increasing price of metals and minerals, which China must face. In order to overcome this challenge, we summarized five points as follows:

- (1)

- China should establish a net price contract as a pricing benchmark for international trade.

- (2)

- China should set up overseas delivery warehouses.

- (3)

- China should promote the overseas registration of domestic futures exchanges.

- (4)

- It is important to complete the laws and regulations, in accordance with international practices, in China.

- (5)

- China should pay attention to the weakness of domestic enterprises.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.X. and Z.G.; methodology, L.X.; formal analysis, L.X.; writing—original draft preparation, L.X. and Z.G.; writing—review and editing, Z.G.; funding acquisition, Z.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by Basic Science Center Project for National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72088101, the Theory and Application of Resource and Environment Management in the Digital Economy Era), and it has also been supported by Hunan Science and Technology Major Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2020GK1021). This research was funded by Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China grant number 2019JJ40040.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data were collected from the internet.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gulley, A.L.; Nassar, N.T. The United States, and competition for resources that enable emerging technologies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4111–4115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schulz, K.J.; DeYoung, J.H.; Seal, R.R.; Bradley, D.C. Critical Mineral Resources of the United States: Economic and Environmental Geology and Prospects for Future Supply; USGS Professional Paper 1802; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Report on Critical Raw Materials and the Circular Economy; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The White House. Executive Order 13817. Executive Office of the President. December 2017. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidentialactions/presidential-executive-order-federal-strategy-ensure-secure-reliable-supplies-critical-minerals/ (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Lin, Y.; Yang, H.; Ma, L.; Li, Z.; Ni, W. Low-Carbon Development for the Iron and Steel Industry in China and the World: Status Quo, Future Vision, and Key Actions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingguo, Z.; Fuyuan, W.; Ruizhong, H.; Shaoyong, J.; Wenchang, L.; Rucheng, W.; Denghong, W.; Tao, Q.; Kezhang, Q.; Hanjie, W. Critical metal mineral resources: Current research status and scientific issue. China Sci. Found. 2019, 33, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.-C.; Wu, X.-D.; Liao, B.; Lin, X.-M.; Cao, L.-F. Simulation of low proportion of dynamic recrystallization in 7055 aluminum alloy. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2021, 31, 1902–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.F.; Ferreira, I.L.; Almeida, R.P.; Castro, J.A.; Sales, R.C.; Zilmar, A., Jr. Microstructural evolution and microsegregation in directional solidification of hypoeutectic Al−Cu alloy: A comparison between experimental data and numerical results obtained via phase-field model. Trans. Nonferrous Metals Soc. China 2021, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Yan-qing, L.; Fang-yang, L.; Liang-xing, J.; Ming, J.; Xi-lun, W. Sb2S3 nanorods/porous-carbon composite from natural stibnite ore as high-performance anode for lithium-ion batteries. Trans. Nonferrous Metals Soc. China 2021, 31, 2051–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xianfeng, Z.; Xiaoliu, Z.; Jie, L. Research on the Development Trend of Bulk Commodity Prices in the Post-epidemic Era-Early 2021 Analysis of the Reasons and Countermeasures for the Rise of International Bulk Commodity Prices. Price Theory Pract. 2021, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gao Shanwen: Reasons, Trends and Policy Responses to This Round of Commodity Price Increases. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1700920236392804853 (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Yanchun, L.; Gongyi, Z.; Xuewu, Z.; Mijia, Z. Strengthen monitoring and guide expectations to curb unreasonable commodity prices; Rise—International commodity price rises and their impact on my country and countermeasures. Price Theory Pract. 2021, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Shijie, L.; Yang, L.; Zhenjiang, H.; Yunjiao, L.; Junchao, Z.; Jing, M.; Kehua, D. Synthesis and properties of single-crystal Ni-rich cathode materials in Li-ion batteries. Trans. Nonferrous Metals Soc. China 2021, 4, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. The World Bank Annual Report. 2004. Available online: https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/0-8213-5971-1 (accessed on 18 September 2021).

- Directive 2003/54/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2003, Concerning Common Rules for the Internal Market in Electricity and Repealing Directive 96/92/EC. Article 4 Regulation (EC) 1228/2003. Off. J. Eur. Union 2003, 176. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/eudr/2003/54/article/4 (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Directive 2003/54/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2003, Concerning Common Rules for the Internal Market in Electricity and Repealing Directive 96/92/EC. Article 3(3). Off. J. Eur. Union 2003, 176. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/eudr/2003/54/article/3 (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Padrós, C.; Cocciolo, E. Security of Energy Supply: When Could National Policy Take Precedence over European Law? Energy Law J. 2010, 31, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2003/54/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2003, Concerning Common Rules for the Internal Market in Electricity and Repealing Directive 96/92/EC. Article 21 and Article 23. Off. J. Eur. Union 2003, 176. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/eudr/2003/54/article/21 (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- World Steel Association. Statistical Data. 2020 Production Ranking of Major Steel Companies. Available online: https://www.worldsteel.org/zh/steel-by-topic/statistics/top-producers.html (accessed on 1 January 2016).

- Amaechi, C.V.; Wang, F.; Hou, X.; Ye, J. Strength of submarine hoses in Chinese-lantern configuration from hydrodynamic loads on CALM buoy. Ocean Eng. 2019, 171, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amaechi, C.V.; Wang, F.; Ye, J. Understanding the fluid-structure interaction from wave diffraction forces on CALM buoys: Numerical and analytical solutions. Ships Offshore Struct. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaechi, C.V.; Wang, F.; Ye, J. Numerical Assessment on the Dynamic Behaviour of Submarine Hoses Attached to CALM Buoy Configured as Lazy-S Under Water Waves. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).