1. Introduction

The recent global trend of population aging has challenged the affordability of families and increased the burden on social security systems, hindering socioeconomic development. Japan, known as the oldest population in the world, had 34.5% of its population aged 60 or over in 2020 [

1]. In Europe, another severely aging region, 27.4% of the European Union population was aged 60 or over in 2021 and it was predicted to reach 37.1% by 2100 [

2]. Countries are required to adapt efficiently to the aging process to achieve sustainable development. An effective social pension system is supposed to meet the various needs of the elderly, which lightens the burden of the next generation and further encourages the rise of the silver economy.

In recent years, residential communities have been considered by policymakers and families as pleasant and economical places for seniors worldwide to enjoy retirement [

3]. In Japan, the “Gold Plan” promoted the community nursing industries to provide health care for the elderly at home [

4]; while the “Social Services Block Grant Program” in the US emphasized the convenience services such as housekeeping and catering to enable the elderly to enjoy high-quality independent living [

5].

China, the most populous country in the world, is under tremendous pressure to mitigate the risk of population aging. The Seventh National Population Census conducted in 2020 evidenced that 18.70% of China’s population was aged 60 or over, amounting to 264 million people. The proportion of the elderly rose by 2.51% [

6] compared to 2010. The China Development Research Foundation has predicted that by 2050, China will have nearly 500 million people aged 60 or over, accounting for about one-third of the total population [

7]. This acceleration of aging is already a major concern for the rights and interests of senior citizens.

The Communist Party of China’s Central Committee proposed the formulation of the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) for National Economic and Social Development and mooted Long-Range Objectives Through 2035 [

8], briefly labeled “the proposals for the 14th Five-Year Plan.” The long-term national strategic task of responsively managing population aging is emphasized in the abovementioned plan in conjunction with the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly (in short, “the Law”) [

9]. The Outline of the Healthy China 2030 Plan also underlines the promotion of community services. It proposes the integration and regeneration of stock resources in existing neighborhoods in addition to the development of home-based care services in new urban communities [

10]. As for the pension benefit, the Basic Old Age Insurance was established in 1951 for urban employees and the Public Employee Pension was started in 1953 to support civil servants and employees in the non-profit public sector. To cover non-employed urban residents and rural residents, the Resident Pension Schemes was established around 2010 [

11]. The financial burden on governments is rising with the aging of the population.

The requirements for elderly care services are increasing in China. The well-being of the aging population is closely related to their living environments. Providing them with a spacious, neat, safe, friendly, and vibrant residential environment will enable the elderly to live a happier, healthier, more active, more affordable, and more inclusive retirement life in society, which will contribute to a better sustainable future.

However, the demands for elderly care in existing neighborhoods in China require further discussion. First, few studies have systematically observed the conditions of their living environment. Second, the theoretical framework has not been applied to the inference of the elderly’s intra-urban mobility for home-based care. Third, a void is noted in nationwide quantitative measurements of the requirements of facilities and services for the elderly in aging communities. When many more seniors than other groups live in aging communities, the housing inequity can lead to greater challenges to sustainable development in an aging society. Moreover, how urban renewal promotes sustainable development in the context of the population remains to be studied.

Therefore, this study focused on the process of senescence in the population of old urban communities in China and illustrated the need to renovate existing resources to ensure healthy aging. The discussion that follows chronologically benchmarks older residents and communities. Elderly residents were defined in this study as people aged 60 or more years [

9]. Old urban communities are denoted as those built before 2000. Since the reformation of the urban housing system was implemented in 1998, housing has been fully commercialized in China, which expanded the housing supply and improved the housing quality significantly in the 21st century. Meanwhile, at the policy level, due to poor facilities and services, the safety needs, and basic living needs of residents were no longer being met, the Chinese government designated the urban communities built before 2000 as the old urban communities which need to be renovated [

12]. The term “urban areas” alluded to municipal districts within cities. The word “concentrated” signified the increased acuteness of population aging in older urban communities. Initially, a facility-and-service-oriented migration model was constructed based on the trend of the community-based endowment to theoretically explain the phenomenon of the high occupancy of aged people in decaying residential communities and elucidate its causes. Next, the living environment and the concentration of senior citizens were evaluated based on China’s 1% national population sample survey to quantify the demand for home-based care services in urban old communities. Subsequently, empirical studies were conducted at the city and individual levels using statistical data from cities and CFPS datasets to verify the mechanism and identify groups facing higher risks.

This study contributes significantly to the intimate relationship between population aging and urban regeneration in several theoretical and practical aspects. The findings demonstrate a connection between population aging and urban renewal by elucidating the concentration of elderly residents in old urban locations exhibiting inadequate living conditions. This study also enriches the description of China’s population aging process by establishing a new approach to interpreting the migration patterns of the urban elderly. Furthermore, it expands the existing theoretical framework for the social benefits of urban renewal from the perspective of the aged population. It will further have great practical significance in supporting the larger financial expenditure on the old communities’ regeneration, as well as identifying the scale of elderly-care requirements and indicating high-risk regions.

2. Literature Reviews

Researchers have investigated the living environments and arrangements of Chinese senior citizens. Home-based care has always represented a favorable pension arrangement in urban locations [

13]. Large cities house solitary households in increasing numbers [

14], raising the requirements for age-friendly communities, which should ensure the safety, health, life satisfaction, independence, and engagement of the elderly in social activities [

15]. The need for long-term care services in urban China has been increasing, especially community services [

16]. Scholars have found many elderly residents in old communities in some Chinese cities [

17,

18], but the ageing resources in old areas were found to be insufficient [

19].

Meanwhile, the elderly’s accessibility to elderly care services would be related to their migration choices. In China, the elderly populations were found to be less willing to move after retirement [

20], which was affected by their motivation, socioeconomic situation, family status, and the characteristics of the origin and destination [

21]. Scholars have summarized that elderly migrants are stimulated by three types [

22], namely, pleasure-oriented [

21], family-oriented [

23], and institution-oriented [

24].

Academics and policymakers believe that a livable environment is crucial for establishing an age-friendly society. Scholars have confirmed that the community environment influences physical and mental health. The overcrowded spaces limit their activities, which would bring on faster the physical and cognitive decline of the elderly residents [

25]. Pollution in older regions has been posing health risks to aged people as well [

26]. Furthermore, community was as important as a family in preventing the retired populations from being isolated in China [

27]. Moreover, an unfavorable living environment would decrease their subjective life satisfaction [

28,

29]. Poor living conditions would increase the risk of depression among the elderly [

30]. So, building multi-sectoral-cooperation to develop home and community care and establish physical and social, age-friendly environments has been deemed an important approach [

31].

However, it is necessary to apply further discussions on the demands for the community elderly care system in existing neighborhoods in urban China. First, the trend of developing community home-based care systems has been agreed in China, but few studies have objectively observed the housing unfairness encountered by the elderly compared with other age groups. Second, there is a set of mature theories for intra-urban migration but it has not been applied to the inference of mobility for the community elderly care systems among the Chinese elderly. Third, the nationwide quantitative measurements of the demands for elderly care in aging communities are required to put forward scientific schemes to advance their well-being.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Theoretical Model

This section elucidates a residential migration model to illuminate the mechanism that allows the concentration of the aging population to accumulate in antiquated housing. The model was developed through a comprehensive adoption of the residential decision-making process, life cycle theory, and stress threshold theory. The residential decision-making process postulates three steps of residential relocation: generating migration intentions, seeking optimal destinations, and moving [

32]. The life cycle theory moots that life events arouse housing aspirations in families and subsequently lead to relocation [

23,

33]. The stress threshold theory posits that stress is induced in households because of a gap between their residential needs and current housing conditions; such families tend to migrate to a new location when the stress exceeds a threshold [

34].

Intra-urban migration has been the main migration pattern among the elderly in urban China. Return migration, the elderly return to the region of their birth after their retirement, was believed to be a typical mode of migration from the urban to the rural areas [

21]. However, the urban–rural pattern mostly appeared in the young-old and a recent study also proved that the elderly were more willing to migrate to more urbanized neighborhoods than the younger generation [

35]. In China, there are large social, economic, and cultural differences between urban and rural areas, so the public infrastructures and services in urban areas are more suitable for senior citizens who used to work in the cities [

13]. Furthermore, the urban elderly preferred to choose home care in their own homes or someplace close to their children [

36]. Therefore, under the rise of urbanization, the urban–rural migration of the Chinese elderly population is negligible.

This investigation focused on the intra-urban migration by the Chinese elderly following the trend of community-based endowment arrangement and inspired by age-friendly housing community facilities and services (

Figure 1). Communities constructed before 2000 were classified as old ones. Thus, the devised model illustrated the mobility of people who moved from an old to a new community between 2000 and 2015. In particular, the study focused on residents aged 60 years or older in 2015 (or people aged 45 or more in 2000 living in housing built before the turn of the century).

Given this context, a higher level of old residents would reside in old communities nationwide. The housing and households would age simultaneously over time in the absence of migration, resulting in a higher proportion of old residents in old dwellings than young or middle-aged inhabitants. Otherwise, if families only moved from one old community to another, they would also reside in timeworn communities. Both instances would yield a higher concentration of senior citizens in neighborhoods constructed before this millennium. The model was developed as follows.

Step 1: The elderly are aging, which is a natural life event that activates their migration process. The population group under study experienced retirement in the last 15 years, which is commonly deemed a major life event; it introduces fresh habitation-related requirements to solve the challenges of aging [

33]. However, their life events are quite simple compared with the younger generation [

23,

33], which results in less necessity for relocation.

Step 2–1: The gap between the emerging aging demands and original aged community conditions is the motivation of the Chinese urban elderly’s intra-urban migration. Home-based care is popular with the elderly in China, whose aspirations for community endowment services and age-friendly environments would hence increase. However, the original accommodation for this age group was built before 2000, and the inconsistency between the housing conditions and living demands generates stress and motivates migration. First, the poor facilities and management [

37] are incompatible with the pension needs of the elderly. Further, the limited living areas and cluttered public spaces make antiquated communities overcrowded, which will further reduce the general level of amenities significantly due to the congestion diseconomies [

38] and drive the residents to newer communities with more complete public services [

39]. Moreover, old residential neighborhoods are mostly located in the city centers; however, the advantageous locations are accompanied by a higher risk of exposure to air pollution and noise in Chinese cities [

26]. However, the complete urban public infrastructure supplies might compensate for the unfavorable community conditions, which in some ways enhance the consistency between aging residents and their current habitations.

Step 2–2: Social connection in original communities retains the old residents. Communities and family are the major social connections of the elderly [

27]. Relocations are hampered by their opposition to the risks of social isolation and loneliness in new neighborhoods [

40]. Meanwhile, a supportive family structure, be it with a spouse and children, might lighten their requirements for the elderly care provided by communities. The push–pull factors given by their original communities work together to the elderly’s potential benefit from resettling in newly built communities that are more likely to offer age-friendly amenities.

Step 3: The potential migrants are challenged by the relocation costs. Sequentially, migration by the elderly entails the stages of searching, purchasing, and moving along with the relevant decision-making processes. A large amount of additional monetary investment, time, and effort must be expended to cover the costs and expenses incurred during these phases, setting a high threshold for most elderly migrants. According to the stress threshold theory, elderly residents will successfully relocate to a new residential community once their potential benefits from the migration exceed the significant extra inputs [

41]. The economic climate will affect their decisions [

42]. Economic prosperity could cause senior citizens to remain in the aging communities because their relative competitiveness would weaken if they opted for new housing. However, the value of existing housing assets could escalate the affordability of elderly homeowners and disperse the concentration.

The entire decision-making process will be influenced by macro- and micro-factors. These potential mechanisms could explain the high occupancy rates of the aged in old housing. Here, we proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). The proportion of the elderly living in old urban communities is significantly higher than the younger generation, and the housing conditions in old urban communities are worse than in the newly built ones.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). The relatively good household economic status would decrease the concentration of the elderly in old communities. The scale of the elderly residents would be lower in cities with lower GDP growth rates and higher second-hand housing prices. Meanwhile, the elderly would be more likely to relocate to newer communities because of the higher family income and sufficient housing assets.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). The social connection provided by supportive family structures and familiar neighborhoods would prevent the elderly from migrating.

3.2. Data Sources

The theoretical model was authenticated via an empirical analysis; household data were compiled from China’s 1% national population sample survey conducted in 2015, city attributes were collected from statistical yearbooks, second-hand housing prices were extracted from a 2015 dataset [

43], and household data were assembled from the 2010 to 2018 CFPS. The main variables are shown in

Table 1. China’s 1% national population sample survey was used to validate the significant concentration of the elderly population in distressed regions of urban China from the microperspective, and this concentration was measured at the city level to illustrate the risks to healthy aging. Next, city characteristics were introduced to explain aging-related divergences between old and new neighborhoods. Then, impediments to the relocation of the elderly were investigated separately based on individual and household samples from the CFPS. The statistics of the variables are shown in

Table A1.

This study assumed housing and individual samples from China’s 1% national population sample survey 2015 to specify the concentration of elderly people in old urban areas. In the 1960s, multistory buildings gradually became residential dwellings for urban residents, with the development of the construction industry [

44] and the application of reinforced concrete materials [

45] and in the datasets, residential buildings built before 1960 accounted for less than 1%. Furthermore, bungalows built in the early 20th century are no longer satisfactory with the realization of sustainable development in cities. Therefore, residential housing units constructed in and after 1960 (excluding self-built rooms and bungalows) were included as housing samples, and residents aged between 20 and 80 comprised the sample population. Housing with living spaces or the number of bedrooms in the upper or lower 5% of the aggregate was excluded. In total, 289 cities with 242,954 residents represented the dataset: 50.39% of the housing comprised old constructions; the elderly represented 19.5% of the population, whose average age was 45.17 years.

Table A1 summarizes the statistics on housing conditions.

City attributes were introduced into the study to analyze city-based divergences of the phenomenon of aging. The differences between the older group (aged 60 to 80) and the younger cohort (aged 40 to 60) of residents of old urban communities were first determined based on China’s 1% national population sample survey to assess the concentration of elderly inhabitants at the city level. How economic performance, public facilities, population status, and housing prices in the stock market affected the agglomeration of the elderly in 251 cities was then investigated. On average, a 10.3% difference was observed between the two groups of residents in old dwellings; thus, older residents suffered from backward living conditions.

Table A1 also summarizes the city attributes.

This study further examined the individual factors affecting the concentration of the elderly in aging neighborhoods. An unbalanced panel dataset was built from 2010 to 2018 based on the CFPS, which is conducted every two years. The characteristics of the households and their urban habitations were thus obtained. Communities constructed in or after 1960 were selected along with households with members aged 60 or more when the survey was conducted. The data included the marital status, educational background, number of children, family income, housing assets, and other relevant information about the elderly residents as independent variables; the age of the housing was employed as the dependent variable. Samples with family incomes in the upper or lower 1% of each province or families with offspring numbering in the upper 1% of the aggregate were eliminated in each round to yield more convincing results, and 9638 samples were examined over five rounds. The average age of the residents was 69.21; the average age of the dwellings was 17.4.

Table A1 presents detailed information on the dataset.

3.3. Models

Econometric methods were applied to investigate the concentration of the elderly in old housing and to quantitatively evidence the mechanisms of this accumulation. t-tests were performed to describe the phenomenon, and regression analyses were conducted to explore potential causes.

The size of the population, the status of old housing, and the living conditions of the elderly in old communities were successively interpreted through a t-test to understand the concentration of the elderly in old urban communities. First, the proportion of residents of each age group in communities erected before 2000 was examined. Second, the living conditions of households in old and new communities were contrasted. Third, the living environments of the aged people in old communities were discussed through comparisons with the younger demographic.

The ordinary least squares (OLS) method was applied to cross-sectional data to investigate how city features contributed to the demographic structure. Concentration was estimated by measuring the percentage of the older group of residents of old communities exceeding the percentage of the younger population of each city to exclude the effects of city-wide residential development levels. A city with a larger estimator would be deemed to encounter more intensive challenges in coping with contradictions between high endowment demands and vulnerable living environments. The movement of aged citizens of such housing to newly built accommodation could be more disadvantaged. Therefore, this figure was taken as the dependent variable in the OLS model. The underlying causes from the macro-perspective were economic development (i.e., regional GDP growth), population structure (i.e., the proportion of the aging population, size of the permanent resident population), residential market performance (i.e., second-hand housing prices), public infrastructure (i.e., rate of green cover), and city development (i.e., percentage of aged communities, the scale of land use for construction). These factors were taken as independent variables. The model was as follows:

where

indicated the concentration of the aging population of old communities in the city

;

,

,

,

and

signified the corresponding characteristics of the city

. The error term was set as

. This model adopted robust standard errors. The notation

denoted the effects of corresponding city factors on the phenomenon of aging populations in old urban communities.

The individual perspective was ascertained through the application of the two-way fixed-effects model with the unbalanced panel dataset from the CFPS. This section of the study aimed to interpret the associations between family structures, economic conditions, and social ties to the departure of the elderly from old dwellings. The number of years elapsed from the construction of the community was established as the dependent variable; marital status, the number of offspring, per capita income, housing assets, and whether the habitation was “reformed housing” were the independent variables. Both individual fixed effects and survey-year fixed effects were included. The model was expressed as follows:

where

represented the age of the housing in which the aged resident

was living in the year

;

,

, and

referred to the characteristics of the resident

in the year t;

denoted the individual sample to flexibly manage other personal attributes that could interfere with the residential status;

represented the survey year to control for nationwide time trends, and

was established as the error term. Standard errors are clustered at the individual level. The term

was expected to signify the effects of the corresponding individual or family factors on the living status of the elderly.

4. Results

4.1. Status Quos of Concentrated Elderly Populations in Old Urban Communities

The agglomeration of the elderly was prominent and prevalent in old urban areas in China. China’s 1% national population sample survey conducted in 2015 evinced a remarkably elevated percentage of elderly residents in old habitations (

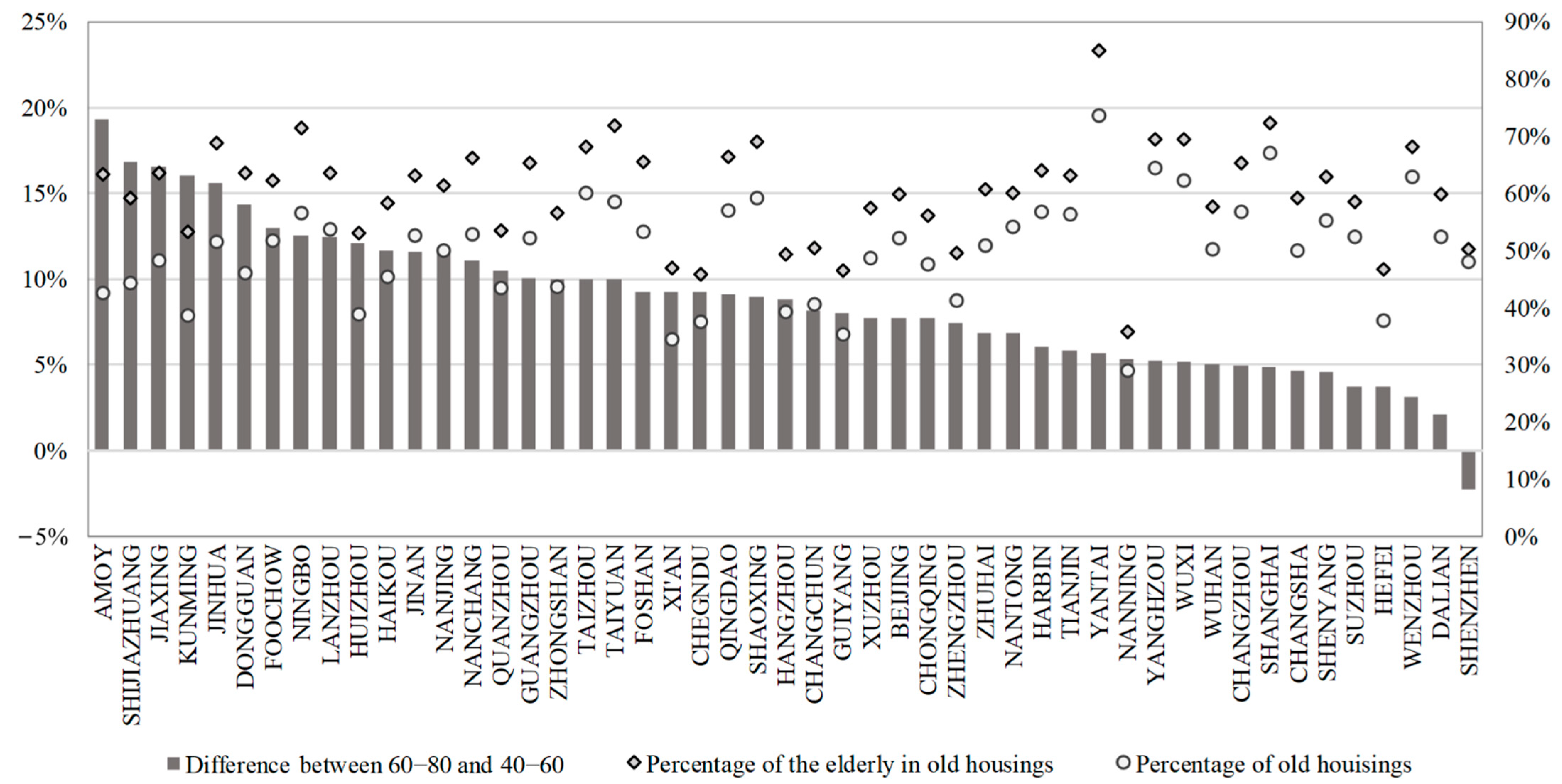

Figure 2).

The older a resident was, the more probable would their practical problems become in moving to new housing. Therefore, the elderly tended to be detained in old neighborhoods. A majority (61.5%) of the elderly aged between 60 and 80 years in urban China resided in communities older than 15 years. This figure has grown by 4.5% since 2005 (

Table 2). Among urban locations, Yantai housed the largest proportion of the elderly in second-tier and above cities at 84.9%. Shanghai took second place with 72.3%. The proportions of the elderly in first-tier cities were 65.2% in Guangzhou, 59.8% in Beijing, and 50.1% in Shenzhen in descending order. Regardless of other possible factors, the absolute scale of the elderly residents of aged communities was highly correlated with, and generally above, the proportion of the older residential communities in the city (

Figure 3).

Given the overall city development, considering the differences between the elderly and the adjacent younger group would be a more suitable method for conceptualizing, measuring, and comparing the gravity of the hidden perils population aging poses to social development. A

t-test was thus performed between the two age groups based on their living circumstances as ascertained from the 1% national population sample survey. The results evidenced the proportion of the elderly was significantly 9.9% higher (

p < 0.01,

Table 2) compared with the younger group in urban China in 2015. Therefore, the aging process of the population and their habitations were developing synchronously. In second-tier cities and above, Amoy housed the highest concentration of aged residents in decaying regions at 19.3%; Shijiazhuang, Jiaxing, Kunming, and Jinhua completed the top five. The environments and services in the old communities in these cities would exert a greater impact on elderly residents. In first-tier cities, the gap was 10.1% in Guangzhou, 7.7% in Beijing, 4.86% in Shanghai, and −2.2% in Shenzhen in descending order. Shenzhen was the only city among the second-tier and above classification to exhibit a negative outcome, largely because it housed numerous residents aged between 40 and 60 years in its old communities. Nonetheless, the scale of the aged group still exceeded the average level (

Figure 3).

The high concentration has never mattered in itself; rather, the aged facilities and weak services expose the elderly to health risks and cause housing inequities among different age groups. This study thus examined distinctions in the attributes of old and new housing communities with the population sample survey. The status of environments older than 15 years has fallen remarkably behind newer constructions in terms of living spaces, facilities, and housing tenures (

Figure 4). The average floor area of living spaces in old housing was 66.56 square meters, significantly smaller than newer residential units by 25.72 square meters (

p < 0.01). The average number of rooms was also 0.25 less (

p < 0.01) in old housing. In terms of facilities, more than 90% of the old dwellings in the sample survey included private toilets or kitchens; however, the percentages in new housing were, respectively, a significant 2.0% and 4.3% higher (

p < 0.01). Furthermore, 60.7% of the residential buildings erected before 2000 were six-storied or below, 19.3% higher compared to the newer units. The investigation of housing properties revealed that 39.8% of the old housing samples were allocated through housing system reformation, and 34.8% over the new constructions. Additionally, commercial housing dominated the sample of new housing units, accounting for 62.1% and exceeding residential units by 30.1%. Therefore, old urban communities in China have always faced conspicuous difficulties concerning age-friendliness.

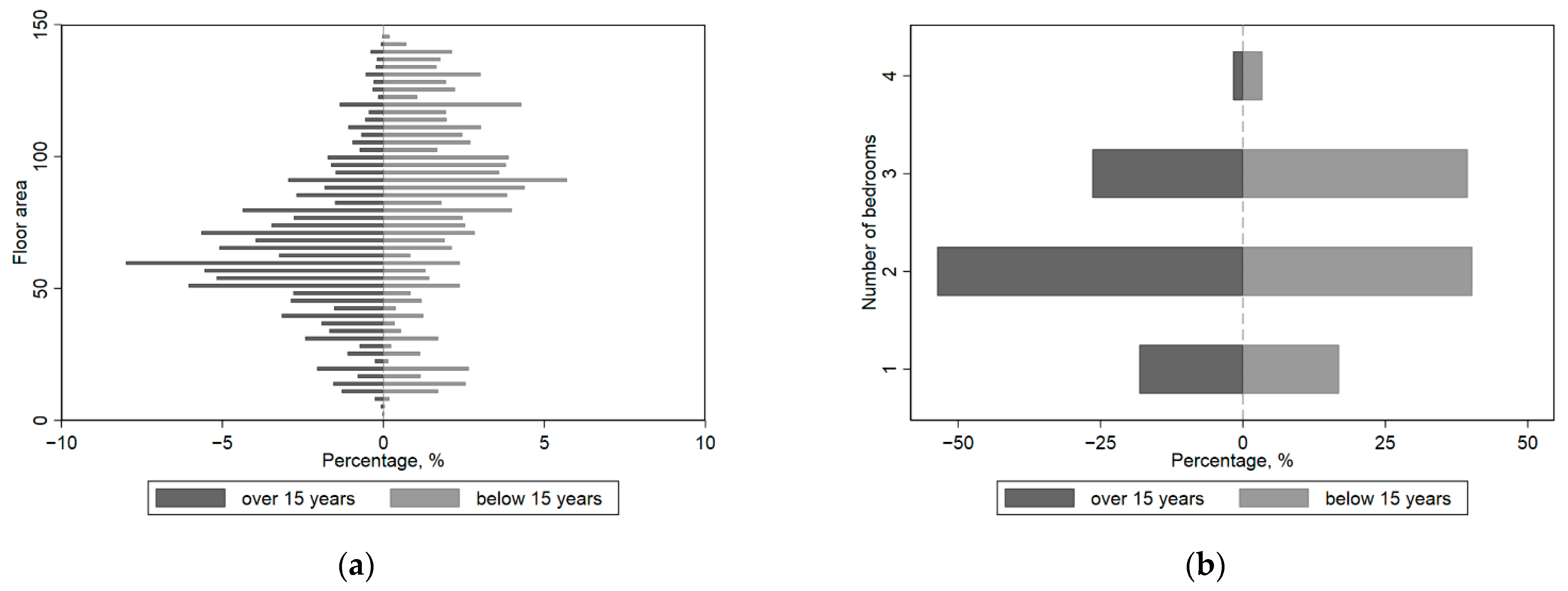

Moreover, the distribution of the elderly in old residences evinced a few disparities apropos housing attributes compared to the middle-aged (

Figure 5). First, elderly residents gathered in communities with long histories. The proportion of the elderly living in communities built between 1970 and 1990 was 5.75% over the middle-aged cohort (from samples ranging from 1960 to 2000, identical to this section). Second, elderly residents tended to be more evident in “reformed housing”, exceeding the scale of the younger group by 15.09%. Third, more senior residents were found in old housing with better conditions; their presence was potentially higher in multistoried residential habitations with private kitchens and toilets. Apart from these aspects, scant variation was observed in living spaces. This study found that the promotion of age-friendly facilities and services was more intensive in communities built between the 1970s and 1990s, established by enterprises/institutions, or composed of multistoried dwellings.

4.2. Causes of Concentrated Elderly Populations in Old Urban Communities

4.2.1. City Attributes

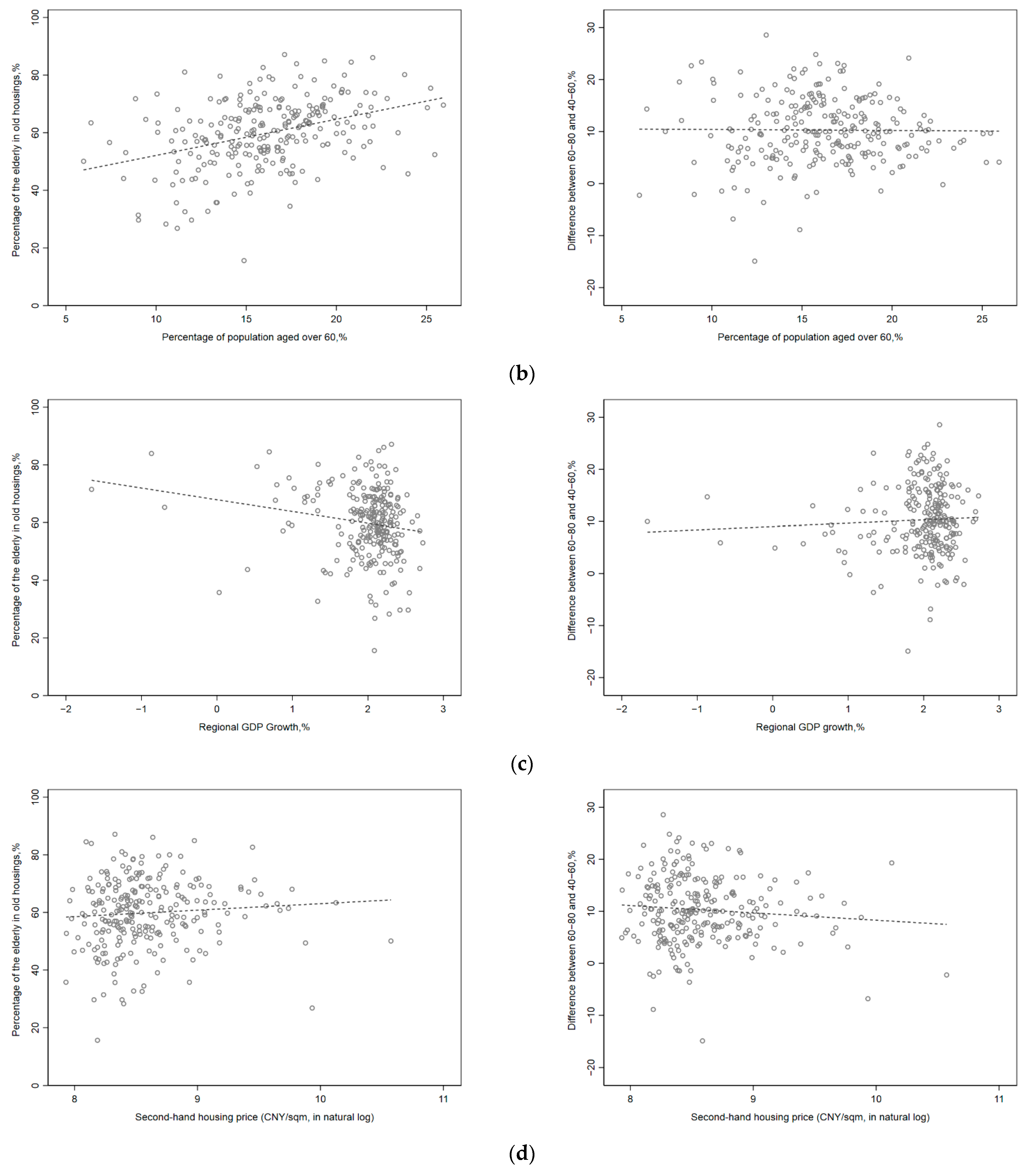

Some city attributes apart from residential evolution contributed to severe population aging in old residential communities. Of the 251 sample cities, those with faster economic growth, more improved public facilities, and more affordable second-hand housing were found to house elderly residents in older dwellings in higher numbers. A correlation also existed between the high occupancy of the elderly and each stated feature (

Figure A1). The regression analysis also found significant factors preventing the elderly from moving to newly constructed neighborhoods (

Table 3).

First, socioeconomic prosperity significantly influenced the concentration of the elderly population: a 1.1% (p < 0.1) larger divergence could be expected between the elderly and the younger group of residents of old urban housing when the GDP grew by 1%. Hence, as per the study’s theoretical analysis, the elderly would be less likely to relocate to newly built communities than the younger populations of fast-growing cities.

Second, the high incidence of senior residents in old neighborhoods was negatively correlated with second-hand housing prices. A 2.4% (p < 0.1) reduction was observed in the disparity between the two age groups living in old communities, along with a 1% increment in housing prices in the stock market. The high prices of existing properties would mitigate the contradictions between elderly-care requirements and the status quo of old communities. The elderly who owned valuable housing assets would command superior opportunities to substitute a vulnerable habitation with a newer construction. Otherwise, depreciating stock assets could barely guarantee affordability, trapping them in old housing communities.

Third, public infrastructure prompted population aging in areas built earlier. The gap in the percentage between the older and younger group widened by 0.1% (p < 0.05) in older housing when the rate of green cover in urban areas was 1% higher. In addition, a 1.3% increment was noted in the dependent variable (p < 0.05) as the per capita length increased by 1% when the per capita length of the drainage pipeline was included as another public infrastructure-level indicator. It could then be extrapolated that the better the public environment and services exhibited by a city, the more conspicuous the phenomenon of aging populations in old urban communities.

This study also contemplated the influences exercised by demographics and construction. The results did not yield enough evidence of any significant connection between the urban population structure and the higher occupancy rates of the aged in old habitations, the population size, or the level of aging. Similarly, the absolute scale of the aged residents of old urban communities was determined; however, the impact of urban construction levels on the disparity of habitation between the older and younger groups under study could not be discerned.

4.2.2. Individual Attributes

Individual variations prevented the elderly from migrating to newly constructed neighborhoods. This phase of the study examined the mechanism of aging populations in old housing from the individual perspective (

Table 4). To this end, it employed individual samples from the CFPS to explore the impact of family structures, household assets, and housing tenures on the ages of residences.

First, family structures exerted a significant influence on the age of the housing communities inhabited by the elderly. Other factors remained consistent, the residence of a non-single elderly individual was expected to be constructed 1.318 years earlier (p < 0.01) than that of a single, aged person (i.e., widowed, divorced, or never married). Similarly, the average housing age would be 0.376 years older (p < 0.01) for every increase in the number of offspring. These findings illustrated that less supportive family structures were more likely to urge elderly citizens to migrate to more advanced living environments suited to their wellbeing in old age.

Second, the age of the community inhabited by the elderly was negatively related to their asset levels. In terms of per capita household income, the elderly in low-income families would be more easily found in older neighborhoods. The housing community’s age tended to be 0.433 years older (p < 0.01) for every 1% difference in the per capita income of households with elderly members. Likewise, the elderly owning more than one house would be more selective in their voluntary migration. Their residences were probably built 0.567 years later than those who owned only one dwelling during the investigation period (p < 0.05).

Third, “reformed housing” communities were significantly older on average than the entire sample of the elderly. An elderly resident of a house allocated through housing system reformation was likely to represent a retiree of an enterprise/institution, and the person’s habitation would be expected to be older by a significant 2.943 years (

p < 0.05) than other types of housing tenures. This outcome aligns with the status quo that the elderly tend to be assembled in old housing communities managed by state-owned enterprises. Meanwhile, “reformed housing” communities also lessened the effect of household income (

p < 0.05,

Table A2). Even wealthier seniors valued the social connection in neighborhoods. The interactions between other opposing factors have not been found to be significant.

5. Discussion

This research initiative aimed to investigate the concentration of aging populations in old urban communities. Higher intensities of aged populations were identified in old urban areas in China, and this incidence varied between cities and households. Cities evincing rapid economic growth, low stock housing prices, and high-quality urban public infrastructure supplies would more urgently require corresponding strategies or relocation of the elderly. Meanwhile, senior citizens who lived with their spouses, had more children, owned fewer family assets, or had retired from state-owned factories were probably exposed to less favorable habitations.

This study contributes significantly to the extant knowledge in several theoretical and practical aspects. First, the findings demonstrated a connection between population aging and urban renewal by elucidating the concentration of elderly residents in old urban locations exhibiting inadequate living conditions. Second, this study established a new approach through which to interpret the migration patterns of the urban elderly; it thus enriched the description of China’s population aging process. Third, the current investigation expanded the existing theoretical framework for the benefits of urban renewal. Furthermore, the analysis furthered the practice of community regeneration by identifying high-risk regions and indicating the urgent requirements of the elderly.

This study found an immense concentration of aged residents in old urban communities, which were deemed insufficient for community home-based endowments. In terms of life cycles, retirement could be the only key life event that could make elderly residents dissatisfied with their current homes. The younger group must move for higher education, better job opportunities, marriage, and parenting [

23,

33], so they will not attach enough importance to local improvements [

46,

47]. In comparison, the older group would naturally require lesser movement. Their original habitations are in poor condition and are not suitable to support their requirements of services for the elderly or the migrated younger generation. Therefore, it established a new approach that can illustrate the social problems related to population aging in urban China, by deliberating on concentrated elderly populations in old urban housing communities. While enriching the study of elderly migration, the theoretical and empirical analyses conducted have revealed the unavoidable nature of this impediment to healthy aging, so promoting community regeneration would be more effective for healthy aging. The results also indicate the necessity of positing age-friendly strategies throughout the renovation; for instance, conducting as many face-to-face negotiations as possible and adopting flexible billing methods for paid installations or services.

The scale of senior residents in crumbling housing was significantly influenced by the economic status of the elderly members. The results revealed that the better the economy of the city developed, the lower the income the elderly received, or the lower the price at which the second-hand housing was valued, the higher the consistency between population and aging housing. Overall housing demand was amplified with rapid economic development, and new short-term housing supplies were relatively inelastic because of the construction life cycle. Aged residents could promptly relocate to their ideal accommodation when they felt uncomfortable with their current circumstances as long as their household incomes or their housing properties were adequate. This outcome implied that retired individuals were less competitive in affording new housing, mostly because they confronted a higher risk of poverty than the younger cohort [

48]. Disadvantageous economic status leaves the elderly with no choice but to adapt to unsuitable living environments. The pensions for the elderly were much lower than the average salary of working people in urban areas. In 2021, retirees received CNY 3349 per month on average from the Basic Old Age Insurance [

49], while the average wage has already reached CNY 8903 [

50]. It was more disadvantageous for the elderly in the Resident Pension scheme with only CNY 190 per month [

51], accounting for less than 10% of the average consumption [

52]. Moreover, housing has always been a significant property for the elderly in China [

53]; thus, their ability to afford a new residence weakens in tandem with the depreciation of the market prices of second-hand housing. This discovery reminds us of the poverty among elderly residents in old urban communities. Given the limitations of the public pension system, the transformation of old urban communities would not only directly improve their living environment but also increase the housing wealth of the elderly. It would diversify the supplies of social welfare and advance social equity for the elderly to actualize shared prosperity. Urban renewal is already acknowledged as an effective means of realizing sustainable urban development [

54], especially in protecting the poor [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]. This study expanded the theoretical framework to incorporate social responsibility vis-à-vis the aging population.

Conversely, the developed public infrastructure supplies aggravate population aging in old urban communities. The consistency of aging populations and housing communities was more conspicuous in cities evincing greater green cover ratios or sound drainage systems. Hence, comparatively improved surroundings and developed infrastructures could effectively satisfy the basic living requirements of the elderly and decrease their willingness to migrate. Perhaps the elderly are highly adapted to antiquated environments. For instance, public pocket parks could serve the leisure requirements of nearby residents, allaying any distress due to the insufficient elbow room in old neighborhoods. Similarly, functional municipal pipe networks could satisfy the essential survival needs of the aged even if they lived in old buildings. It may then be assumed that the austerity and conservatism of senior residents render them less conscious of the upgrading demands than younger generations. This study supports the formulation of renovation plans by prioritizing the strong demands of the aged population, given their appreciation of elementary functions and their unfamiliarity with advanced promotions. This investigation also suggests enhancing the elderly’s cognition of potential risks to encourage the involvement in revitalizing their communities into age-friendly neighborhoods.

Moreover, social connections affect the relocation of the elderly: supportive families or intimate neighborhood relationships hinder the resettling of older individuals in new housing communities. Old residents with more immediate relatives probably prefer the traditional family support pattern to the community pension system [

60]. They would choose to live closer to their children rather than reside in better neighborhoods. Furthermore, influenced by traditional cultural values, the elderly would save for their children rather than promote their own well-being [

61]. Thus, spouses and offspring mitigated the sensitivity of the elderly to external risks, despite potentially lowering the pressure of relocation costs and additional inputs. Older residents also prefer to stay in “reformed housing” with their former colleagues and old friends. This study further evidenced the attraction senior citizens feel toward intimate neighborhoods that enable a healthier and more satisfying quality of life [

17,

62,

63,

64]. Renovated housing communities could revitalize neighborhoods [

65,

66] while preserving the equity, relationships, and cultural values [

67,

68] of the original residents. Thus, this study postulated the significance of rehabilitating old communities. Such actions would protect the elderly from having to adjust to unfamiliar surroundings and relieve the younger generations from the load of traditional family support. Hence, these findings recommend prioritizing the transformation of residential units constructed by old enterprises/industries and strengthening their publicity among young households.

Therefore, this study encourages the mutual promotion of a community-based pension system and the transformation of aged communities. From one perspective, renovating old communities would enable great numbers of older individuals to live more healthily without having to endure heavy financial burdens, undertake exhausting migration, or confront unfamiliar settings. The insufficient supply of institutional care can be compensated for and the burdens of traditional family support can be effectively lightened in this manner. Increases in financial support for community regeneration could enhance future coordination. From another perspective, highly prioritizing age-friendly infrastructure endorses the people-oriented concept of community renewal. Such actions elicit resident initiatives to rehabilitate their housing and surroundings by serving their practical aging needs and further benefit sustainable urban development.

6. Conclusions

Establishing age-friendly cities has already been a crucial task for achieving sustainable development worldwide. This study established an intimate relationship between population aging and urban regeneration. First, the theoretical model illustrated the residential mobility following the trend of community-based endowment arrangement for the Chinese elderly. Second, the measurements demonstrated that the proportion of the elderly living in old urban communities was significantly 9.9% higher than the ratio of the middle-aged (aged 40 to 60). Third, the investigation revealed that the elderly population concentration varied among cities and individuals because of their disadvantageous economic status, simple lifestyle and strong social connections.

Therefore, to improve the welfare of older populations and achieve the urban sustainable development goals, this study recommends enhancing policy-based coordination between the urban renewal schemes and the establishment of elderly care services. First, given the strong demands of the aged population in the old urban communities are prominent, the governors should prioritize the establishment of care-for-the-elderly systems in the regions built earlier, according to the concentration of the elderly, when formulating the urban renewal schemes. Second, it is suggested that the government should provide more financial support for the renewal of the community, especially the renewal of old-age facilities and services. Considering the inadequate pension benefits, the additional financial support will afford the renovation cost for the elderly residents, thereby improving the welfare of the old populations. It can be regarded as a redistribution of wealth by the government to the elderly. It is necessary to hold face-to-face events for senior residents, strengthen the advocacy among their offspring, enhance their cognition of potential risks in the decaying living environments and encourage their involvement in revitalizing their communities. The coordinated improvement of the elderly care system and the regeneration of old communities will advance age-friendly environments and supplement the government’s redistribution of pension benefits. It will make the elderly happier, healthier, wealthier and more satisfied with their retirement life.

This study conceived the connection between population aging and urban renewal, expanded the existing theoretical framework for the improvement of social welfare in urban renewal, and offered guidelines for the transformation of old urban communities. However, since the discussion on the requirements of community care of the elderly relied on the measurement at city levels in this study, we can hardly describe the demands precisely. Moreover, we discussed the status of the old urban communities at a specific time rather than the change across the period, so we cannot directly quantify the impacts of the community transformation on the elderly’s well-being. Further studies are needed to support the promotion strategies. First, the investigation of senior residents’ subjective evaluations and requirements of the community renovation will be carried out. Then, we will quantitatively measure the impacts of the community improvements on the elderly residents by using real community regeneration cases, to predict the potential supplement to the social pension system and direct the subsidization of the mooted concept. Furthermore, the behavior patterns of the elderly will be ascertained, to pertinently propose organizing strategies to promote the public interest.