Abstract

The way consumers dispose of end-of-life products (EoL products) and their acceptance of recycled products largely determine the final direction of resource flow. Therefore, clarifying consumers’ preferences for end-of-life scenarios (EoL scenarios) and recycled products and guiding consumers to participate in a circular economy is of great significance for enterprises and society to transition to a circular economy. However, as far as the existing research is concerned, there is a lack of comparison and summary of consumer preferences based on multi-category EoL products and recycled products. Therefore, this study took four categories of common consumer durables as the object to study consumers’ preferences for EoL solutions and recycled products and, based on the survey results, user segmentation in the market and consumer type segmentation in the CE were performed. The research results show that users generally support product reuse, and they generally have the highest acceptance of second-hand products and the lowest acceptance of refurbished products; meanwhile, consumers’ acceptance of recycled products varies by product type; according to the differences in preferences, consumers are divided into groups with different consumption characteristics; based on the differences in support for product recycling and recycled products, consumers are divided into the high perception group, the general perception group, and the low perception group in CE. The results of this study can provide reference for related research on sustainable waste management and sustainable consumption.

1. Introduction

The circular approach to the disposal of EoL products in the circular economy breaks the “take–make–use” model of resource use in the linear economy [1,2] and ensures that society’s resources flow in a circular manner in the form of products, components, and materials [3]. Consumers are important stakeholders in the CE [4,5], as many researchers, including Antikainen et al., have shown that the circular economy has high expectations of consumers who will play a key role as its enablers [6,7,8,9]. In a study set in the context of the second-hand clothing trade market, Machado et al. [10] summarized the consumer engagement in the virtuous circle framework of the CE, demonstrating that consumers have a key role in it. Hazen et al. [11] argue that consumers represent the key nodes in the closed-loop supply chain of the circular economy, as they decide when and where to end product use and how to dispose of waste products, as well as whether to purchase new or remanufactured products; for the circular economy to stand, consumers need not only to return used items after use, but also to purchase remanufactured products. In a study on consumer disposal of e-waste, Islam [12] stated that the end user or consumer is the starting point of multiple pathways for e-waste to start entering the CE; Wastling et al. [13] argued that users and their behavior can have a significant impact on the overall flow of products, components, and materials and that users and their behavior have become an integral part of the business-to-consumer (B2C) model; Guide and Wassenhove [14] stated that the issue of consumers’ propensity to purchase remanufactured products is critical to society’s eventual transition to the circular economy. From this literature, it can be seen that society as one of the three main actors in the circular economy (government, business, and society) [15], is not only the “exporter” of EoL products, but also the “gateway” to recycled products. The way people dispose of EoL products determines the final destination of the resource [16], while their acceptance of recycled products determines whether recycled products can be circulated in the market, which is the last link in the closed-loop flow of the resource [11]. Therefore, it is important to study consumer preferences for EoL scenarios and recycled products and guide consumer participation in the circular economy for the implementation and development of the circular economy.

From the green manufacturing system based on the 3R principle [17] to the closed-loop system of sustainable manufacturing based on the 6R principle [1], various strategies for recycling end-of-life products have been developed, such as “Reuse, Remanufacture, and Recycle”, also known in some studies as the EoL scenarios [3]. Bocken et al. [18], building on Stahel [19], McDonough and Braungar [20], and Braungart et al. [21], proposed a strategic framework for the CE at the product design and business model level, with “slowing, closing and narrowing the resource loops” as the main approach. The closed-loop strategy focuses on the transformation of waste resources into materials with the same properties as the original material through different levels of processing, but the level of recycling depends on the technical requirements and cost effectiveness. According to Alamerew et al. [22], the current approach to recycling and disposal of EoL products is mainly made from a product or corporate perspective and decision-making, focusing on technical and economic factors and ignoring the key area of consumer needs and preferences. It has been shown that while the literature on the circular economy is growing, there is a dearth of research exploring consumer preferences for EoL scenarios [23]. Some relevant studies in recent years have mainly explored consumers’ disposal preferences for EoL products in the electronics and appliances category [12,24], and there is a lack of studies on consumers’ recycling disposal preferences for different categories of consumer durables corresponding to EoL products. Therefore, consumer preferences for recycling and disposal methods for different categories of EoL products was one of the key points that this study was trying to understand.

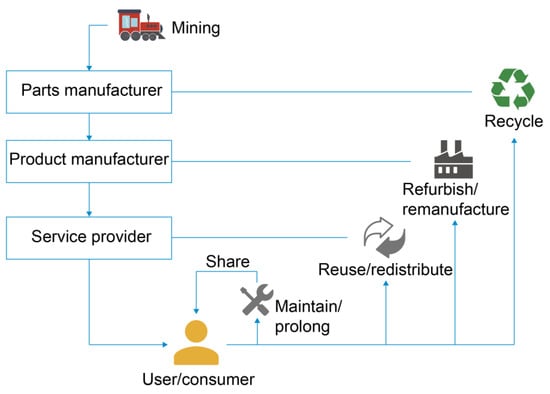

According to the definition of recycled products by Essoussi et al. [25], any EoL product that is recycled and then reenters the market can be called a recycled product. In a complete closed-loop resource flow cycle (Figure 1), EoL products start from the user, are reused, refurbished, remanufactured, and recycled, and then successfully flow through the manufacturer or distributor to the user. The purchase and use of recycled products by consumers is an important node in the closed-loop CE supply chain, as revealed by many past studies [11]; studies on consumer acceptance and perceptions of recycled products can predict the future of the recycled product market and facilitate policymakers to make timely adjustments to recycled product services and markets in response to user feedback [24]. Therefore, consumer acceptance and perception of recycled products is another issue that this paper aimed to explore. The studies conducted on consumer acceptance of recycled products have mainly selected the electronics and appliances category [24,26], clothing [10] and textiles [27], or single categories such as reused products [10] and remanufactured products [28]; other single recycling methods of recycled products have been researched and explored; in terms of content, the factors that influence consumer acceptance or rejection of recycled products are mainly explored [6,28], and there is a lack of user perspective on the comparison of multiple categories and types of recycled products. Another research issue in this study aimed to clarify consumer acceptance of different categories and different types of recycled products.

Figure 1.

Map of closed-loop resource flows, adapted with permission from Ellen MacArthur Foundation [5] and Islam et al. [12].

Taking the above research background and description together, the aims of this paper can be summarized as follows:

- Understanding consumer preferences for EoL scenarios of different product categories.

- Understanding consumer preferences for recycled products of different product categories and different recycling types.

- Based on the above two questions, the breakdown of consumer preferences under different product categories of the consumer durables market.

For the purpose of the study, the research process consisted of two parts. The first was one was product selection. Firstly, different categories of consumer durables were identified as the product background for this study, and then a suitable number of representative products were selected from each category to facilitate the interviewees’ intuitive understanding of the different categories of consumer durables.

The second part was data collection: an online questionnaire combined with a seven-point Likert scale was used to ask consumers about their “preference for EoL scenarios and recycled products” in different product categories.

2. Literature Review

To address the direction of this study, this section describes and discusses three sections of the relevant research literature on consumer preferences for EoL scenarios, consumer preferences for recycled products, and consumer segmentation in the CE.

2.1. Consumer Preferences for EoL Scenarios

There are biases or overlaps in the summaries of EoL product disposal strategies in different studies [1,29,30]. As Alamerew et al. [22] stated, this is mainly because there is currently no uniformity in the academic definition of each strategy. As the main objective of this paper was to clarify consumer preferences for product disposal at the end-of-life stage, product disposal strategies at the use stage or at the design stage after product recycling were excluded. Therefore, four EoL scenarios with high relevance to consumer behavior and decision-making—“reuse, refurbishment, remanufacturing and material recovery”—were selected for the study of consumer preferences. Reuse is defined as “the use of the product again for the same purpose in its original form or with little advancement or change” [3]. Refurbishment is the process of restoring a product to a satisfactory working or cosmetic condition, which may be inferior to its original condition, by repairing, replacing, or refinishing the major components that have been significantly damaged [7]. Remanufacturing means the process by which an original equipment manufacturer (OEM) or a third party contracted by it disassembles an obsolete product into its components and reassembles components that may have come from a different old product with as few new parts as possible in order to create a product with the same performance and quality as the new product [7]. It is important to note that the new product made from old components may not be the same as the original product, a process defined in some studies as “cannibalization” [22]. According to Marcel’s definition of the concepts related to product design for recycling research, the term “recycling” refers to material level-based recycling strategies, primarily the process of collecting, processing, and using waste materials for the production of new materials or products and is, therefore, different from the broader concept of recovery [31]. For the sake of distinction, this paper referred to material level-based recycling strategies as material recovery.

In previous studies on consumer preferences for the disposal of EoL products, the preference has been more for the daily disposal of end-of-life products, e.g., Islam et al. [12] conducted a literature review on consumer behavior related to the consumption, storage, disposal, and recycling of e-waste and found that storage at home was the most common disposal method for e-waste, in line with the findings of Gurunathan et al. [4]. In another study on consumer preferences for EoL scenarios, Atlason et al. [3] investigated how end users perceive the three EoL scenarios (reuse, remanufacture, and material recovery) for end-of-life household electrical and electronic products, and the results showed that reuse was the most supported EoL product recycling option. Atlason et al. [3] mainly chose EoL products as the context for their study, but their approach to product selection decisions, data collection and analysis methods were important references for this study. Apart from this, there are fewer studies on consumer preferences for EoL scenarios, and the main product categories involved are electrical and electronic end-of-life products (e-waste), as shown in many recent reviews of the literature [12,32,33]. Secondly, most studies only selected reuse [33], refurbishment [34,35], and remanufacturing [26] as one or two EoL scenarios as the research context; there is a lack of comparison and choice of multiple EoL scenarios by users. Therefore, consumer preference for EoL scenarios based on different product categories is one of the topics that we would like to investigate in this paper.

2.2. Consumer Preferences for Recycled Products

Calvo-Porral et al. [36] argue that consumer acceptance of recycled products is a key factor in ensuring the success of circular business models. Hazen et al. [11] examined the consumers’ willingness to purchase remanufactured products in a study, and the results showed that consumers’ attitudes towards remanufactured products were an important predictor of whether consumers would purchase and use remanufactured products. The above literature suggests that studying consumers’ attitudes towards recycled products can inform and hedge the risks for companies that want to go for a circular business model. With regard to surveys of consumer acceptance and preference for recycled products, Boyer et al. [37] used a joint analysis to test the willingness to pay a premium for mobile phones and smart hoovers that explicitly carry the “circular economy” label among more than 800 respondents in the UK, and showed that consumers prefer products that are “circular” when they have less than a certain percentage of recycled components. Almulhim et al. [38] used a questionnaire to gauge awareness and attitudes towards CE strategies in Saudi Arabia, with some results showing a growing interest in environmentally friendly goods, but most respondents were concerned that reused or shared products could threaten their health, especially during the new coronavirus pandemic. Factors influencing consumer purchases of recycled products have also been a hot topic of recent research in the field of the CE. The literature published by Mugge et al. [34] summarized consumer perceptions of refurbished phones from the existing studies and showed that, overall, consumers are less likely to purchase refurbished products, but that improving the perceived quality, attractiveness, and durability of a product can increase the users’ willingness to purchase [39]. By surveying 49 consumers on their willingness to pay (WTP) for seven different types of products, Essoussi and Linton [25] cross-examined the impact of the product category and the way products are recycled on the consumers’ WTP for recycled products, showing that the former has a significant impact because of the different perceived functional risks of different product categories; the lower the level of functional risk associated with a product, the greater the WTP for it; this is consistent with the findings of Hein [28]. Mobley et al. [40] also indicated that the consumers’ quality evaluation of recycled products is influenced by the product category. These studies all suggest that consumer preferences for recycled products may vary according to the product category and the recycling method. Therefore, the effect of the category of recycled products and the method of recycling on consumer preferences is another topic that this paper wanted to explore.

2.3. Consumer Segmentation in the CE

In a study investigating consumer preferences for EoL scenarios, Atlason et al. [3] found that women preferred all EoL recycling disposal methods more than men and were more willing to pay a higher price for eco-friendly electronics, suggesting that gender may be an important basis for user segmentation. In addition, Wang and Guo [41] from Zhejiang University of Science and Technology in China investigated the factors affecting the recycling behavior of used and end-of-life electronic products from three major aspects, showing that internal factors such as recycling experience, environmental awareness, and ethical norms, external factors such as economic factors, information dissemination, and recycling channels, and demographic factors such as age, gender, and education level all have an impact on the people’s intention to recycle. The segmentation of consumer samples corresponding to different categories according to user preferences and the description of users in relation to demographic characteristics are also topics that this paper wanted to explore further, which is helpful to producers in various industries to effectively implement circular business models in relation to consumer types and preferences. In addition, Wallner et al. [35] conducted a survey on 785 consumers using refurbished headphones as an example; they divided consumers into four major groups according to the refurbished product attributes they focused on and proposed circular design strategies for each of the four consumer groups. Finally, this paper hoped to derive the differences in consumers’ perceptions of the CE by studying the consumers’ support for EoL scenarios and recycled products and then classify consumers into different consumer groups in the CE and propose strategies to enhance CE participation for different types of consumers.

3. Methods

3.1. Product Selection

Consumer durables are mainly goods with high elasticity of demand, high unit value, and long service life [42]. Compared to fast-moving goods, durable goods are generally purchased less frequently and consumed in larger amounts, so consumers are more cautious and rational in their purchases and decisions [43], which is why consumers’ disposal of durable goods at the EoL stage can more accurately reflect consumers’ disposal preferences for end-of-life products. In addition, consumer durables generally utilize more resources during the production and manufacturing stages, and extending the life cycle of consumer durables can promote the maximum use of resources. Therefore, this paper used EoL products and recycled products corresponding to consumer durables as a medium for studying consumer preferences. According to the classification of consumer spending by the National Bureau of Statistics of China, consumer durables are divided into the following four main categories: household appliances, transportation, communication tools, and cultural, educational and recreational products [44]. Referring to Atlason et al.’s product and product category selection in a study investigating user preferences for different EoL scenarios [3], this study decided to select three (or fewer) products from each of the four major categories of consumer durables with high popularity, easy accessibility, and significant differences in elements such as volume, materials, and functionality as representative products in each category. The categories of consumer durables and the representative products selected are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Consumer durable product categories and the products selected for this study.

3.2. Pre-Experiment

To ensure the quality of a questionnaire, a small number of samples need to be collected for the reliability and validity analysis before the formal experiment begins in order to identify problems in the questionnaire items. At the same time, the standard deviation and absolute error values in the sample size calculation equation were determined through the pre-experiment [45,46] to prepare for the determination of the sample size in the formal experiment [47]. The pre-experiment was conducted through an online questionnaire, which was distributed and collected over a period of two days. A total of 68 users participated initially, targeting people aged 18 to 60 with relatively high decision-making power and purchasing power. An overview of the participant information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

General description of the pre-experiment participants.

The questionnaire explored two main issues: (1) domestic consumer preferences for EoL scenarios for different types of EoL products; (2) consumer preferences for recycled products with different recycling methods under different categories. Referring to the questionnaire design in Atlason et al.’s study of consumer preferences for EoL scenarios for electrical and electronic appliances [3], this questionnaire consisted of three main modules: (1) questions related to basic information such as gender, age, and education; (2) preferences for EoL scenarios for end-of-life products corresponding to the four categories of consumer durables without regard to the cost and complexity of disposal under the two premises of functional perfection and functional impairment (since product reuse requires that it be carried out under functional perfection, EoL products under each category are subdivided into two cases of functional perfection and functional impairment of the product); (3) the acceptance of recycled products of different recycling methods (used products, remanufactured products, refurbished products, and recycled material products) under the four categories of consumer durables. The questions in modules (2) and (3) were seven-point Likert scale-type scored questions [34]. For example, in an EoL scenario preference survey for household appliance products with intact functions, the question was set as follows: “If you no longer use household appliance products such as refrigerators, soybean milk machines, tables and chairs, but the main functions of the product are still intact, without considering the cost and complexity of disposal, how would you like to dispose of this product? Please rate the following three ways of disposal, with 7 being very supportive and 1 being very unsupportive.” In order to avoid jargon that would burden the participants’ understanding, the options in the questions were organized in easy-to-understand language; for example, the circular disposal method of reuse was explained as “transfer to another person for reuse through regular channels”. Based on the information from the three modules, the questionnaire consisted of 16 questions, including four demographic questions, eight questions on EoL product disposal preferences, and four questions on the acceptance of recycled products.

3.2.1. Reliability and Validity Tests

A total of 68 questionnaires were returned, of which 63 were valid. The results of this study were analyzed in SPSS 26.0 to determine the reliability and validity of the questionnaire. The reliability of the scale questions was analyzed using the common Cronbach’s coefficient. The results are shown in Table 3, where the reliability coefficient (i.e., Cronbach’s coefficient) was 0.933, which was significantly greater than 0.900, so the questionnaire was highly reliable. KMO and Bartlett’s tests were used to test the validity of the questionnaire by grouping the questions in each category related to consumer durables into one set, plus the final question on recycled product-related questions, for a total of five sets of validity tests. The results are shown in Table 4. The KMO values for all five tests were greater than 0.6, and Bartlett’s sphericity test p-values were all 0.000 (<0.05), proving that the questionnaire passed validity and was valid.

Table 3.

Results of the reliability test of the questionnaire.

Table 4.

Results of the questionnaire validity tests.

3.2.2. Determination of the Sample Size

As this study was a simple random sampling study with an infinite overall population, the sample size required for this study could be estimated based on the sample size formula. The formula for calculating the sample size is as follows:

In the formula, is often taken as 1.96 (); σ is the standard deviation of quantitative data; δ is the absolute value of the permissible error, i.e., the result of multiplying the mean value by the margin of error [45,46]. The samples collected from the pre-experiment were imported into SPSS 26.0 for descriptive statistics and the results obtained are shown in Table 5. Taking the maximum standard deviation σ as 2.185, the minimum mean value of 3.41, and a 5% margin of error, δ was determined to be 0.17. Bringing the above variables into Equation (1) yielded an estimate of the sample size (n) of 641, so the number of people surveyed in this experiment must not have been less than 641. The study ultimately lasted seven days, and 989 questionnaires were collected online, of which a total of 926 valid questionnaires were used as the sample size for the formal experiment. An overview of the final participant information is shown in Table 6.

Table 5.

Results of the pre-experiment descriptive statistics.

Table 6.

Overview of final experiment participant information.

4. Result

4.1. Data Analysis

Consumers were classified into different consumer groups using K-means cluster analysis through SPSS 26.0 software, with reference to the research methodology of Wallner et al. on consumer segmentation [35]. The K-means algorithm is a typical division-based clustering method that aims to divide n data objects in the original dataset by a specified number of classes so that data objects within the same class have a high degree of similarity to each other, while data objects between different classes have a low degree of similarity [48]. The preference questions for EoL programs and recycled products in each category of consumer durables were clustered once, before and after four times. User segmentation of consumers with different preferences by cluster analysis can help companies and designers identify potential consumers in their industry through demographic characteristics and choose differentiation strategies to encourage consumers to recycle end-of-life products in their business models or designs; or combine users’ preferences for different types of recycled products to guide them to purchase recycled products.

4.2. Consumer Preferences for EoL Scenarios for Different Consumer Durables

The preliminary results of the questionnaire (Table 7) show that the most preferred EoL scenario was reuse for each of the four types of EoL products: household appliances, transportation, communication tools, and cultural, educational, and recreational products; in terms of the overall score of EoL scenarios, the reuse strategy had the highest average score of 6.01. This result is consistent with the findings of Atlason et al. [3] on user perceptions of EoL scenarios, suggesting that user preferences are largely aligned with the concept of the circular economy. Of the other three, only the material recycling strategy scored higher, at 5.61, while refurbishment and remanufacturing scored significantly lower. Cross-sectionally, consumers are most supportive of reuse strategies for EoL products in the transportation category and most resistant to refurbishment of EoL products in the communication tools category.

Table 7.

Consumer EoL scenario preferences.

4.3. Consumer Preference for Recycled Products for Different Consumer Durables

Table 8 depicts the consumers’ acceptance of products recycled by different recycling methods under different categories. Looking at each of the four categories of recycled products, the users’ most preferred type of recycled products was used products; however, the rating of used products varied depending on the product category. The results show that there was a clear difference in the overall consumer acceptance of the different categories of recycled products—interest in the communication tools category was significantly the lowest, while the other three categories of recycled products were rated higher and not too far apart. This is in line with previous research findings [44] and may be related to the perceived risk to consumers of different categories of recycled products [35,43]. In terms of the type of product being recycled, consumers rated the other three categories higher and more or less equally. In terms of the types of products recycled, consumers were most receptive to second-hand products and least receptive to refurbished products. Overall, consumers were least willing to buy and use refurbished products in the communication tools category, with an average score of 4.59 on the Likert scale, and most receptive to second-hand products in the arts, education, and entertainment category, with an average score of 5.64 on the Likert scale.

Table 8.

Consumer preferences for recycled products.

4.4. User Segmentation in the Consumer Durables Market Based on User Preferences

From the initial results above, it can be seen that the EoL scenarios preferred by consumers may have varied with the type of products; similarly, consumer acceptance of recycled products also varied by product category. The questionnaire results for each of the four major categories of consumer durables were clustered to achieve the corresponding market user segmentation for each category. The four clusters achieved convergence through 16, 11, 11, and 9 iterations, respectively, which, to some extent, illustrates the validity of the results. The clustering results are shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Consumer clustering results under different categories of consumer durables.

4.4.1. Household Appliances

The responses relating to the recycling of EoL products and the purchase of recycled products in the household appliances category were clustered into three categories, meaning that the consumer sample was divided into three types based on the ratings. The first group consisted of 510 people, mainly highly educated and high-income people aged 31–60, accounting for around half of men and women, respectively; they gave the highest overall ratings to the EoL scenarios, with the number of cluster centers ranging from 0.122 to 0.461, and their ratings were ranked as remanufacturing > refurbishment > material recovery > reuse. This group of users also rated the recycled products in the household appliances category the highest, with the number of cluster centers ranging from 0.428 to 0.619, with the ranking of remanufactured products > refurbished products > recycled material products > used products. The second group of 308 people, mainly those aged 18–30 and 41–50 with low income, accounted for 31% and 35% of the men and women, respectively; the number of cluster centers for these users’ ratings of the EoL scenario ranged from −0.339 to 0.078, with the ranking of material recovery > reused > remanufactured > refurbished. In terms of acceptability of recycled products, the cluster centroids of their ratings ranged from −0.657 to −0.451, with the ratings ranked as recycled material products > used products > refurbished products > remanufactured products. The third group of 108 people, mainly low-income people aged 18–31 and 51–60, with insignificant gender and education characteristics, gave the lowest overall rating to the EoL scenario, with cluster centroids ranging from −1.695 to −0.058, with a ranking of reuse > refurbishment > remanufacturing > material recovery. In terms of acceptability of recycled products, they also had the lowest ratings, with cluster centroids ranged from −1.233 to −0.548, ranked as used products > remanufactured products > refurbished products > recycled material products.

4.4.2. Transportation

The sample in the transport category section was also clustered into three groups. The first group consisted of 525 consumers, mainly aged 31–60, highly educated, and high-income, accounting for 63% and 53% of the male and female samples, respectively. Of the three groups, they rated the four EoL scenarios the highest overall, with cluster centroids ranging from 0.095 to 0.512, with ratings ranked as remanufacturing > material recovery > refurbishment > reuse. They also gave the highest ratings to recycled products, with the number of cluster centers ranging from 0.330 to 0.562, with the ranking of refurbished products > recycled material products > remanufactured products > used products. The second group consisted of 312 people, mainly at the lower end of the income scale, between 18 and 30 years old, with more women and less distinctive educational characteristics. Their cluster centroids for the four EoL scenarios ranged from −0.404 to −0.186, and their ratings were reuse > refurbishment > remanufacturing > material recovery. The cluster centroids for their ratings of recycled products ranged from −0.498 to 0.254, ranked as used products > remanufactured products > recycled material products > refurbished products. The third group consisted of 89 people, mainly low-education, low-income people aged 31 to 60 years old, with insignificant age and gender characteristics. Their ratings of the EoL scenarios and recycled products were both the lowest of the three groups. The cluster centroids for their ratings of the EoL program ranged from −1.820 to 0.094, with the ranking of reuse > material recovery > refurbishment > remanufacturing. The cluster centroids for their ratings for recycled products ranged from −1.745 to −1.054, with the ranking of used products > recycled material products > refurbished products > remanufactured products.

4.4.3. Communication Tools

The samples in the communication tools category section were clustered into two main groups. The first group consisted of 634 people, mainly high-income, 30–50 years old, accounting for 73% and 66% of the male and female samples, respectively, with no obvious educational characteristics. They rated the four EoL scenarios highly, with cluster centroids ranging from 0.157 to 0.437, with ratings ranked as remanufacturing > material recovery > refurbishment > reuse. They also rated the four recycled products more highly, with cluster centroids ranging from 0.310 to 0.480, in the following order: refurbished products > remanufactured products > recycled material products > used products. The second group, comprising 292 people, was dominated by low-income people aged 18 to 30 and 51 to 60, accounting for 27% and 34% of the male and female samples, respectively, and still with no significant educational characteristics. The second group generally scored lower in two areas: the cluster centroids for the communication tools EoL scenario ranged from −0.950 to −0.342, with the ranking of reuse > refurbishment > material recovery > remanufacturing; for recycled products, the cluster centroids ranged from −0.042 to −0.672, with the ranking of used products > recycled material products > remanufactured products > refurbished products.

4.4.4. Cultural, Educational, and Recreational Products

The responses related to the cultural, educational, and recreational category were also divided into two groups. The first group consisted of 697 people, mainly high-income people over 30 years old, with a balanced proportion of men and women and no obvious educational characteristics. They rated the four EoL scenarios higher overall, with cluster centroids ranging from 0.134 to 0.356, ranked as remanufacturing > material recovery > refurbishment > reuse. The four recycled products were also rated highly, with the number of cluster centers ranging from 0.271 to 0.369, in the order of remanufactured products > recycled material products > refurbished products > used products. The second group consisted of 229 people, mainly low-income people aged 18–30 years old, with gender and education characteristics remaining insignificant. Their ratings were lower in both areas: they rated the EoL scenario with cluster centroids ranging from −1.084 to 0.407, ranked as reuse > refurbishment > material recovery > remanufacturing. They also rated recycled products generally lower, with cluster centroids ranging from −1.123 to −0.825, with a ranking of used products > refurbished products > recycled material products > remanufactured products.

5. Discussion

5.1. Types of Consumers in the CE

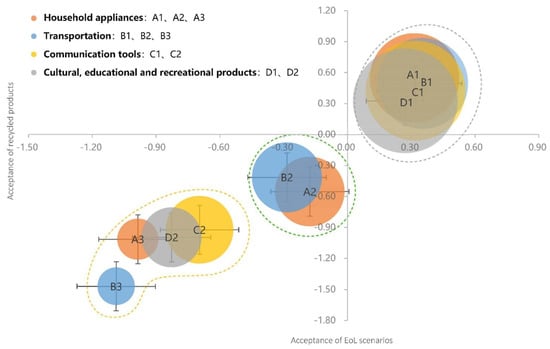

The purpose of typing consumers under the CE is to help market decisionmakers and designers understand the differences in the perception of the circular economy among different consumer groups, which is beneficial for companies and environmental authorities to avoid risks or target users [49] and to use differentiated strategies for user types to guide their participation in the circular economy [50,51]. In order to analyze the differences in consumer perceptions of the circular economy, the consumer segmentation research methodology of Wallner et al. [35] was used to classify consumers into different consumer groups under the CE based on their support for the EoL scenarios and their acceptance of recycled products. Using the consumers’ ratings of the EoL scenarios and recycled products as two-dimensional evaluation criteria, the 10 groups of consumers obtained through clustering under different categories were divided to create the user type bubble diagram in Figure 2. The area size of the bubble represents the size of the consumer sample, and the code at the center of the bubble indicates the clustering category of consumers under different categories in Section 4.4, e.g., A1 represents the first category of users under the household appliances category. It should be noted that since the clustering of consumers in this paper was based on the context of different consumer durables, the samples of consumers represented by the different colored bubbles in the diagram may overlap, with bubbles of the same color added together to represent the overall sample. In this study, user support for EoL scenarios and recycled products was seen as the likelihood of user participation in the circular economy, which translates into the degree of consumer acceptance and perception of the CE. Referring to Gazdecki et al.’s method of describing consumer groups by naming them based on group characteristics [52], this study described different consumer groups in terms of how high or low they perceived the CE. Thus, the sample of consumers in the bubble diagram can be classified as the high perception group, the average perception group, and the low perception group in the CE. Table 10 summarizes the groups representative of the three types of consumers in this study and their attitudes towards EoL scenarios and recycled products, and also summarizes the demographic characteristics of the different groups.

Figure 2.

Bubble chart of user segmentation based on the four consumer durables categories.

Table 10.

Consumer typology in the CE.

Overall, there was a majority of people who were supportive of both end-of-life product disposal and the purchase of recycled products, representing more than 50% of the total sample, such as the segments A1, B1, C1, and D1 in the bubble chart. This group of consumers can be considered a high perception group in the CE and may be an important object of significant value for the environmental sector and the market for recycled products. The centers of bubbles A2 and B2 were located close to the origin of the coordinates, from which it can be seen that this group of users had no obvious support or opposition to the recycling of waste items for disposal and the use and purchase of recycled products, and their level of perception of the circular economy was average. However, under the guidance of the concept of sustainable development, they were likely to develop into potential consumers in line with the value orientation of the circular economy. Therefore, the A2 and B2 groups can be considered as the general value targets for the circular economy. For users in the A3, B3, C2, and D2 categories, the ratings were lower in both dimensions, so they probably had the lowest overall perception of the circular economy. These types of users can be considered as the priority targets for the circular economy.

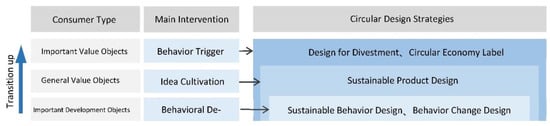

5.2. Circular Design Strategy Based on Consumer Type

In view of the differences in the level of CE perception among different types of consumers, the circular design framework was developed on three levels: behavioral trigger, concept development, and behavioral design, and differentiated strategies were adopted to intervene in the value concepts and behaviors of different types of consumers. The circular design strategy model is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Cycle design strategy based on consumer type.

The results of the study show that important value objects have a stronger overall perception of the circular economy and therefore can be stimulated or guided to participate in the circular economy by adding trigger points in the consumer’s behavioral pathway. For example, Poppelaars et al. [53] summarized a set of design principles in “Design for Divestment”, using smartphones as an example, in the hope that design interventions can facilitate the voluntary return of products at the end of their life cycle. It is also possible to refer to Laura et al.’s use of the Fogg Behavioral Model to persuade consumers to enhance their product care behavior [16], using design to add triggers to the consumer behavioral pathway to increase motivation to recycle EoL products and purchase recycled products. In terms of marketing recycled products, as this group is more concerned about the environment than other consumer groups, they may be more receptive to products that carry the “circular economy” label [28]. Therefore, eco-labels such as “environmentally friendly” and “sustainable” can be used in the design and promotion of recycled products to attract this group of environmentalists.

For general value objects, they only support sustainable behavior in the recycling phase of EoL products and are less accepting of recycled products; while for general development objects, their attitude towards the circular economy is not very clear and it is difficult to see a clear position; both consumer groups are only willing to participate in the circular economy to a certain extent. The book Circular Design Guideline [54] published by the Taiwan Design Institute clearly states that “ideal circular design should be able to successfully communicate sustainable value propositions to consumers and effectively enter into the customer’s perceived value”. Therefore, for this type of consumer mentioned above, a starting point can be to enhance their perception of the circular economy. In terms of design, the concept of circular economy can be incorporated into product elements such as functional design, material selection, name definition and use experience. For example, the Never Wasted eco-friendly shopping bag designed by Happy Studio India for Lee [55], each paper bag can be disassembled and reassembled into a bunch of fun small objects such as pen holders, bookmarks and card holders. This eco-friendly paper bag embodies the sustainable concept of recycling resources and making the best use of them, from the name of the series, the use of materials to the functional design, and has received a strong response from consumers, making it an effective means of spreading the idea of a circular economy. The consumer’s behavioral path leads them to adopt a preferred way of disposing of EoL products or buying recycled products of greater interest; followed by positive feedback at the end of their sustainable behavior, so that they clearly understand the significance of their sustainable behavior for sustainable development and enhance their perception of the circular economy. At the same time, the focus is on what they are not yet satisfied with and measures are taken to improve their user experience in CE and to guide them towards the transition to “important value objects”.

The “important development target”, second in number to the “important value target”, is clearly opposed to sustainable behavior in both phases. They are positioned as an important development target because they make up a relatively high proportion of the sample; and in terms of the results of this study, they are the group in the sample with the weakest perception of the circular economy. If the marginal group of consumers in the circular economy system can be motivated to participate in the circular economy, then the proportion of users participating in the circular economy will effectively increase. At the level of circular design, design for sustainable behavior (DfSB) [56] can be adopted for this group of users: the environmental and social impact of products is reduced by taking into account the use and disposal phases of the product in the design process and by influencing the way users interact with the product through design. For example, Bhamra et al. [56] observed that users spend most of their time opening the door of a fridge looking for items on the bottom shelf or moving items between shelves to make room for new items; as a result, designers can develop refrigerator shelves with better storage and a clear layout to reduce the amount of time the door is left open by reducing the user’s rummaging and transferring of products, thus reducing the energy consumption of the refrigerator over time. In addition, Wastling [13] defined a “Consumer Circular Behavior Model” of CE expectations, outlining key behavioral objectives to consider when designing products or developing solutions for a circular economy; and created a corresponding “Circular Behavior Design Framework” designed to help companies and designers develop product intervention strategies to encourage consumers to engage in the circular behaviors of the Circular Behavior Model. At the circular design level, reference can be made to existing research on sustainable behavioral design strategies [56] and behavior change design strategies [13]. The aim is to guide consumers to engage in circular behavior without changing their awareness.

The Circular Design Strategy Model was developed to help companies and policy makers intervene at different levels of focus to improve consumers’ perceptions of the circular economy and thus their participation in it. However, there are no clear boundaries between the use of different strategies. In particular, design strategies that are used for groups of consumers with a low perception of CE can also be used for groups of consumers with a high perception of CE.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

A synthesis of the consumer survey and the various analyses and discussions designed for this study led to the following conclusions, both theoretical and practical. On the theoretical side, we have two important findings. Firstly, consumer preference for EoL scenarios varies by product category. For household appliances and cultural, educational and recreational EoL products, consumers’ preferences for the four EoL scenarios are ranked as: reuse > refurbishment > remanufacturing > material recovery; for transportation and communication tools EoL products, consumers’ preferences for the four EoL scenarios are ranked as: reuse > material recovery > remanufacturing > refurbishment. It can also be seen that the reuse end-of-life product recycling and disposal strategy is the most supported EoL scenario by consumers, which is in line with Atlason et al. [3] on consumer preferences for end-of-life electronic and electrical appliances. And the difference lies in the fact that this study expands the category of end-of-life products from electronic and electrical appliances to four categories of consumer durables, namely household appliances, transportation, communication tools, and cultural, educational, and recreational products, based on the classification of consumer goods by the National Bureau of Statistics [43]. Overall, the four EoL scenarios mentioned here are ranked in order of consumer support, regardless of the type of end-of-life product: reuse > material recovery > refurbishment > remanufacturing.

Secondly, consumer preference for recycled products is not related to product category, but only to the extent to which recycled products are recycled or processed. Regardless of the category of recycled product, consumer support for different types of recycled products is ranked as follows: used products > recycled material products > remanufactured products > refurbished products; also, overall consumer acceptance of used products is the highest, echoing general consumer support for the reuse strategy for EoL products. In previous studies of consumer acceptance of recycled products, Essoussi and Linton compared users’ willingness to pay (WTP) for different categories of recycled products at different levels of recycling [25], for example, comparing consumer WTP for recycled paper vs. refurbished printers. This study adds a control variable for product category, which can be seen as a follow-up to their study.

In practice, we classify consumers into different categories depending on their level of perception of CE. In this paper, users in different consumer durables sectors were firstly segmented according to the differences in consumers’ ratings of EoL scenarios and recycled products under different categories, and the samples corresponding to “household appliances, transportation, communication tools and cultural, educational and recreational products” were clustered into “3, 3, 2, 2” clusters respectively. The EoL scenario preferences and recycled product preferences of consumers in different clusters were summarized, along with the demographic characteristics of each cluster, to help industry decision-makers identify target users through demographic variables. Secondly, the CE perceptions of the 10 (3 + 3 + 2 + 2) consumer clusters were evaluated in terms of both EoL product disposal and recycled product purchase, and the 10 consumer clusters were categorized into three types of consumers, namely “high perception group, average perception group and low perception group” in CE. In addition, the demographic characteristics of the three groups of consumers have been summarized in order to more clearly target which groups support CE. Finally, a circular design strategy is proposed for the different types of consumers in terms of behavioral triggering, conceptual development, and behavioral design, with the aim of providing a reference for research on enhancing consumer engagement in CE.

6.2. Research Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

This study aims to understand consumers’ perceptions of CE by investigating their support for the EoL scenarios and their willingness to purchase and use recycled products, and to provide a reference on consumer attitudes for practitioners in different consumer durables industries who are ready to shift to a circular business model, so that they can adopt differentiated strategies to guide their participation in the circular economy. However, there are still a few limitations to this study. Shi et al. [57] argue that consumers perceive value across the five stages of pre-acquisition, early use, mid-use, late use, and pre-disposal, whereas this study only describes consumers’ perceptions of CE by investigating their attitudes and opinions at the pre-acquisition and pre-disposal stages. Therefore, it is worthwhile to explore in depth the consumer perceptions of CE as reflected by consumer attitudes and behaviors during the product use stage in subsequent studies. Secondly, this paper only examines the results of consumer preferences for different EoL scenarios, different categories and different recycling methods for recycled products, while the reasons for consumer satisfaction or otherwise are not reflected in this study; there are relevant studies in past research on the factors influencing consumer acceptance of recycled products, which may be related to factors such as product functional risk [25] and product category [40], and subsequent research could investigate the factors influencing consumer perceptions of Factors affecting consumer support for EoL scenarios and recycled products could be further explored in subsequent studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C., H.L. and C.Z.; Data curation, Y.C.; Formal analysis, H.L.; Funding acquisition, H.L.; Investigation, Y.C.; Methodology, Y.C. and C.Z.; Supervision, C.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Our work was supported by Anhui Province Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project under grant No. AHSKQ2021D127. In addition, we are also grateful for the support from all mask users and experts in this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jawahir, I.S.; Bradley, R. Technological elements of circular economy and the principles of 6R-based closed-loop material flow in sustainable manufacturing. Procedia CIRP 2016, 40, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellner, J.; Lederer, J.; Scharff, C.; Laner, D. Present potentials and limitations of a circular economy with respect to primary raw material demand. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 494–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlason, R.; Giacalone, D.; Parajuly, K. Product design in the circular economy: Users’ perception of end-of-life scenarios for electrical and electronic appliances. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan, A.; Shanmugam, P.; Mark, G.; Kaliyan, M. Reuse assessment of WEEE: Systematic review of emerging themes and research directions. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 287, 112–335. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards a Circular Economy: Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition. 2015. Available online: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/towards-a-circular-economy-business-rationale-for-an-accelerated-transition (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- Antikainen, M.; Lammi, M.; Paloheimo, H.; Rüppel, T.; Valkokari, K. Towards Circular Economy Business Models: Consumer Acceptance of Novel Services; The ISPIM Innovation Summit: Brisbane, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Den Hollander, M.C.; Bakker, C.A.; Hultink, E.J. Product Design in a Circular Economy: Development of a Typology of Key Concepts and Terms. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, M.V.; Bakker, C. A product design framework for a circular economy. In Proceedings of the PLATE Conference, Nottingham, UK, 17–19 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mugge, R.; Schoormans, J.P.L.; Schifferstein, H.N.J. Design Strategies to Postpone Consumers’ Product Replacement: The Value of a Strong Person-Product Relationship. Des. J. 2005, 8, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.A.D.; Almeida, S.O.; Chiattone Bollick, L.C.; Bragagnolo, G. Second-hand fashion market: Consumer role in circular economy. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 23, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, B.; Mollenkopf, D.; Wang, Y.C. Remanufacturing for the Circular Economy: An Examination of Consumer Switching Behavior. BSE 2016, 26, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Huda, N.; Baumber, A.; Shumon, R.; Zaman, A.; Ali, F.; Hossain, R.; Sahajwalla, V. A global review of consumer behavior towards e-waste and implications for the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, 128297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wastling, T.; Charnley, F.; Moreno, M. Design for circular behaviour: Considering users in a circular economy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wassenhove, L.N.; Guide, V.D.R. The evolution of closed-loop supply chain research. Oper. Res. 2009, 57, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, C.; Zhou, K. A Quantitative Assessment Method for the Development of Circular Economy and its Application, 1st ed.; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2020; pp. 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann, L.; Mugge, R.; Schoormans, J. Consumers’ perspective on product care: An exploratory study of motivators, ability factors, and triggers. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Shi, Y.; Xia, Q.; Zhu, W. Effectiveness of the policy of circular economy in China: A DEA-based analysis for the period of 11th five-year-plan. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 83, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; De Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; Van der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. JIPE 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahel, W. The utilization-focused service economy: Resource efficiency and product-life extension. In The Greening of Industrial Ecosystems; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 178–190. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things, 1st ed.; North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Braungart, M.; Bondesen, P.; Kälin, A.; Gabler, B. Specific public goods for economic development: With a focus on environment. In Public Goods for Economic Development; United Nations Industrial Development Organization: Vienna, Austria, 2008; pp. 109–141. [Google Scholar]

- Alamerew, Y.A.; Brissaud, D. Circular economy assessment tool for end of life product recovery strategies. J. Remanufacturing 2019, 9, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscicelli, L.; Ludden, G.D.S.; Lloyd, P.; Bohemia, E. The potential of Design for Behaviour Change to foster the transition to a circular economy. In Proceedings of the DRS 2016, Design Research Society 50th Anniversary Conference, Brighton, UK, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kuah, A.T.H.; Wang, P. Circular economy and consumer acceptance: An exploratory study in East and Southeast Asia. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essoussi, L.H.; Linton, J.D. New or recycled products: How much are consumers willing to pay? JCM 2010, 27, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, D.; Jena, S.K.; Tripathy, S. Factors influencing the purchase intention of consumers towards remanufactured products: A systematic review and meta-analysis. IJPR 2019, 57, 7289–7299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, M.M.; McEnally, M.; Widdows, R.; Herr, D.G. Consumer behavior toward recycled textile products. J. Text. Inst. 2000, 91, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, N. Factors Influencing the Purchase Intention for Recycled Products: Integrating Perceived Risk into Value-Belief-Norm Theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, E. Towards the circular economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2013, 2, 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Toffel, M.W. Strategic management of product recovery. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2004, 46, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phulwani, P.R.; Kumar, D.; Goyal, P. From systematic literature review to a conceptual framework for consumer disposal behavior towards personal communication devices. J. Consum. 2021, 20, 1353–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsini, F.; Gusmerotti, N.M.; Frey, M. Consumer’s circular behaviors in relation to the purchase, extension of life, and end of life management of electrical and electronic products: A review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugge, R.; Jockin, B.; Bocken, N. How to sell refurbished smartphones. An investigation of different customer groups and appropriate incentives. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallner, T.S.; Magnier, L.; Mugge, R. Do consumers mind contamination by previous users? A choice-based conjoint analysis to explore strategies that improve consumers’ choice for refurbished products. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 177, 105998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Porral, C.; Lévy-Mangin, J.P. The circular economy business model: Examining consumers’ acceptance of recycled goods. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, R.H.W.; Hunka, A.D.; Linder, M.; Whalen, K.A.; Habibi, S. Product labels for the circular economy: Are customers willing to pay for circular? Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, A.I.; Abubakar, I.R. Understanding public environmental awareness and attitudes toward circular economy transition in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, M.S.; Shokouhyar, S. Actual consumers’ response to purchase refurbished smartphones: Exploring perceived value from product reviews in online retailing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, A.S.; Painter, T.S.; Untch, E.M.; Unnava, H.R. Consumer evaluation of recycled products. Psychol. Mark. 1995, 12, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Guo, L. A Review of Research on Factors Influencing Environmental Behaviour in the Recycling of Used and Waste Electronic Products. Chin. J. Ergon. 2019, 25, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, T. Resarch on the difference of consumer durables in various regions based on weighted factor cluster. Math. Inpractice Theory 2021, 51, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Q.; Qu, Z. Analysis of regional differences in consumption of consumer durables by urban residents in China. Consum. Econ. 2016, 32, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Yin, Q. Development history and trends of consumption of consumer durables by urban residents in China. Enterp. Econ. 2018, 37, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, F.; Wang, Z. Application of K-means clustering analysis in the body shape classification. J. Donghua Univ. Nat. Sci. 2014, 40, 593–598. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W.; He, F. Sample size calculation for status survey. Prev. Med. 2020, 32, 647–648. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Li, K. A comparative study on sample size calculation methods. Stat. Decis. 2013, 1, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- An Efficient k-Means Clustering Algorithm. 1997. Available online: https://surface.syr.edu/eecs/43/ (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- Jaiswal, D.; Kaushal, V.; Singh, P.K.; Biswas, A. Green market segmentation and consumer profiling: A cluster approach to an emerging consumer market. BIJ 2020, 28, 792–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straughan, R.D.; Roberts, J.A. Environmental segmentation alternatives: A look at green consumer behavior in the new millennium. JCM 1999, 16, 558–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. JCM 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazdecki, M.; Goryńska-Goldmann, E.; Kiss, M.; Szakály, Z. Segmentation of food consumers based on their sustainable attitude. Energies 2021, 14, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppelaars, F.; Bakker, C.; Van Engelen, J. Design for divestment in a circular economy: Stimulating voluntary return of smartphones through design. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwan Design Institute. Circular Design Guideline, 1st ed.; Taiwan Design Institute: Taipei, China, 2021; pp. 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H. Design Guidance Analysis of Shopping Bag Based on Green Consumption Behavior. Art Des. 2018, 2, 107–109. [Google Scholar]

- Bhamra, T.; Lilley, D.; Tang, T. Design for sustainable behaviour: Using products to change consumer behaviour. Des. J. 2011, 14, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Huang, R.; Sarigöllü, E. Consumer product use behavior throughout the product lifespan: A literature review and research agenda. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 114114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).